Structural Racism and Inequity in the U.S. Aviation Industry: Foundations and Implications (2024)

Chapter: 4 Economic System of Racial Capitalism

4. ECONOMIC SYSTEM OF RACIAL CAPITALISM

LEARNING GOALS

This chapter includes four subsections that describe the ideological and functional correlations between slavery, the racialized exploitation and compartmentalization of labor in the United States, and mass incarceration as the basis for racial capitalism’s legacy within aviation. This chapter allows the reader to:

- Develop a deeper understanding of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and the history of chattel slavery in the United States as an intentional and violent extraction of racialized African people for economic value in the interest of white wealth.

- Recognize how the labor of racialized people was significant in the development of foundational transportation infrastructure yet the labor system was structured to inhibit their economic advancement.

- Identify present-day examples of harm, such as segregation and wealth inequality within the aviation industry.

INSIGHT WARM-UP

Historical Context

The legacy of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and the centuries of chattel slavery that followed is directly linked to the inequities experienced by Black people today. U.S. transportation infrastructure networks were built with the forced labor of enslaved persons and the labor of underpaid, exploited racialized workforces. What do you know about the connections between racism, labor, transport infrastructure, and personal mobility?

![]()

Lenses and Ways of Knowing

Social science scholars define racial capitalism as “the process of gaining social and economic value from the racial identity of another person.” What do you observe in today’s economy that might be an example of racial capitalism?

Throughout U.S. history, racialized people have been subjected to legal and social limitations that seek to control or limit movement, behavior, culture, and decision-making. Are you familiar with the ways that contemporary policing and mass incarceration trends are related to transportation and racial capitalism?

Present-Day Legacies in Aviation

Multiple airport and aviation careers were established with institutionalized occupational segregation. Significant racial and gender gaps in the airport and aviation workforce persist today. Racial capitalism has greatly contributed to generational wealth inequality (especially for Black families), while many on-site airport jobs continue to compensate workers with unlivable wages. Additionally, airports can facilitate the movement of human trafficking victims, and airports have contracted with companies that rely on laborers in the prison-industrial complex.

4. ECONOMIC SYSTEM OF RACIAL CAPITALISM

Throughout history, whiteness has provided social (Jensen 2020) and economic (Baldwin 2012) value to those who possess it. Today, scholars refer to this “value” or the process of obtaining it as a function of racial capitalism within society (Leong 2012). Racial capitalism can be defined as “the process of gaining social and economic value from the racial identity of another person” primarily through the commodification of racialized bodies (Leong 2013). Racial capitalism theories illustrate how the mandate of productivity within capitalist societies stems from slavery as the early means of the accumulation of resources and power and assert that capitalism is always racialized (Gilmore 2018). Jodi Melamed explains that “The term ‘racial capitalism’ requires its users to recognize that capitalism is racial capitalism. Capital can only be capital when it is accumulating, and it can only accumulate by producing and moving through relations of severe inequality among human groups […] procedures of racialization and capitalism are ultimately never separable from each other” (Melamed 2015).

Political theorist Cedric Robinson formulated the idea of racial capitalism in Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, originally published in 1983 (Robinson 2020). Robinson’s work laid the foundation for theorizing the relationship between capitalism and racism and remains relevant in contemporary social justice movements (Kelley 2017; Issar 2021). Robinson argues that capitalism and racism evolved from old feudalistic systems into a modern system of “racial capitalism” in western societies today. Robinson states that capitalism “emerged within the feudal order and flowered in the cultural soil of a western civilization already thoroughly infused with racialism” (Robinson 2020). In further emphasis on the influence of racialization he states, “Race was its epistemology, its ordering principle, its organizing structure, its moral authority, its economy of justice, commerce, and power” (Robinson 2020). Robinson (2020) argues in opposition of Marxist principles that place emphasis on differences amongst class instead of race: “The development, organization, and expansion of capitalist society pursued essentially racial directions, so too did social ideology. As a material force, then, it could be expected that racialism would inevitably permeate the social structures emergent from capitalism.”

The genocide of indigenous people and the enslavement of African people are two examples of the most violent forms of racial capitalism in history (Leroy and Jenkins 2021). Through acquisition of stolen land and slave labor, racial capitalism proved to be profitable as America established itself as a global force in militarization and economic trade (Morgan 2021; Osterweil 2020). Even after the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. constitution, which partially abolished slavery, racial capitalism evolved in ways that continue to oppress, isolate, criminalize, and imprison racialized and low-wealth people (Leroy and Jenkins 2021). Racial capitalism prevails throughout society today, and “impedes progress toward racial equality” (Leong 2013)). The reality of racial capitalism today is a result of the historical inequities experienced by racialized communities namely, commodification (Leong 2013), exploitation (Burden-Stelly 2020), violence (Melamed 2011), subjugation (Leroy and Jenkins 2021), criminalization (Ralph and Singhal 2019), segregation (Fluri et al. 2022), and incarceration (Calathes 2017) which will be explored further throughout this chapter.

“We can’t eradicate racism without eradicating racial capitalism.” - (Davis 2020)

An example of racial capitalism within transportation includes the mistreatment of Black and Latinx essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Laster Pirtle 2020). Despite the global state of

emergency, essential workers, who were mostly Black or Brown (Gwynn 2021) were pressured to work to provide “essential” services including grocery workers, transit workers, airport workers, etc. (J. C. Williams et al. 2020). Many of these workers were denied hazard pay, had limited sick leave, worked extremely long shifts, and lacked access to healthcare from their employers (Poteat et al. 2020; Gwynn 2021). This mistreatment proved to be tragic in some cases as essential workers were reported to get sick, or even died to meet the demand for labor (Poteat et al. 2020).

4.1 The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and Chattel Slavery

The Trans-Atlantic slave trade and the history of chattel slavery in the United States represent an intentional and violent extraction of racialized people for economic value in the interest of White wealth. The origins of the racist outcomes of spatial harm can be traced back to the Trans-Atlantic slave trade (Wilkerson 2011). The Trans-Atlantic slave trade initiated the involuntary, forcible, and essentially permanent transport of approximately 12 million Africans to Latin America, the Caribbean and the United States to work as slaves (Ngwe 2012; Magee 2009).

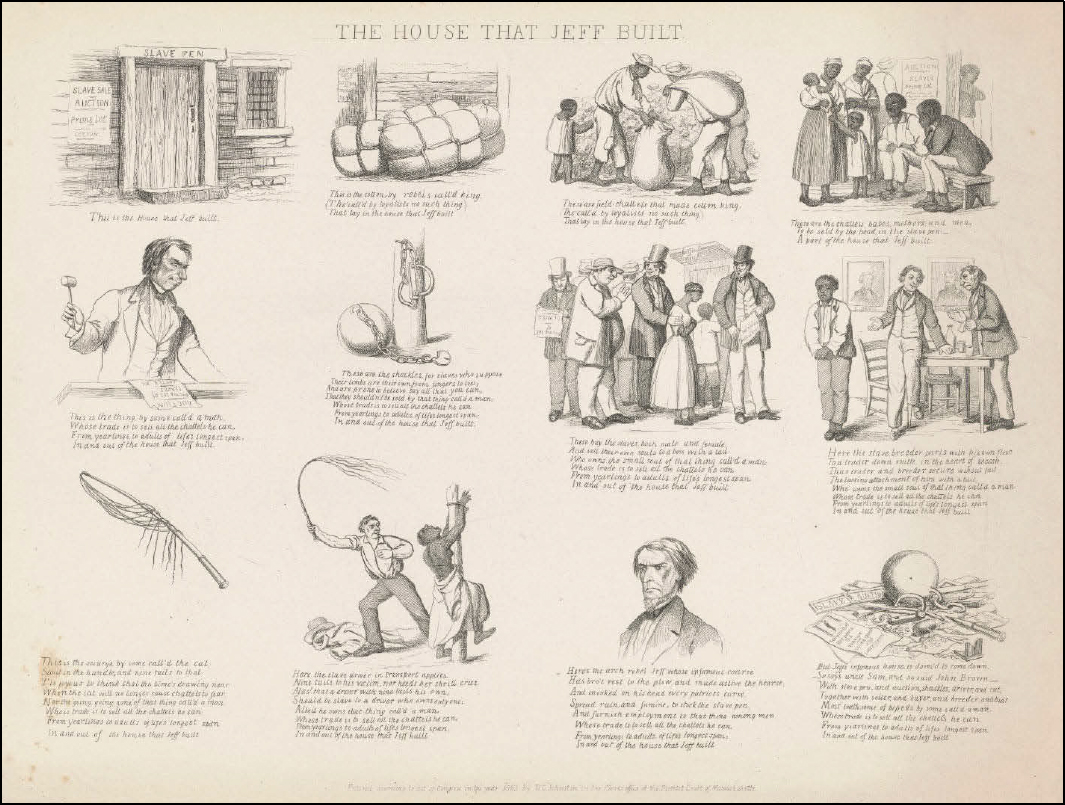

Chattel slavery, distinct from the general term slavery, refers to a “race-based institution” in which one is granted legal ownership of another human being (Zimmerman 2011). The European colonies on the American continent, and ultimately the new nation of the United States, practiced the system of chattel slavery from the 17th to 19th century. Historians refer to chattel slavery as a “physical and cultural transplantation” (Berlin 2009). Settler colonialism (see Chapter 3) and white supremacy ideologies (see Section 2.1.2) legitimized the use of African chattel slavery to achieve colonial desires (i.e., Manifest Destiny) (M. A. Morrison 2000; Gómez 2018). Figure 12 depicts David Claypool Johnston’s political cartoon titled The House that Jeff Built, which condemns chattel slavery in the United States and the southern secessionist leaders, namely Jefferson Davis (“Jeff”). The text of the 12 cartoon panels is transcribed below the image.

The legacy of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and the centuries of chattel slavery that followed is directly linked to the inequities experienced by Black people today in the United States. Scholars attribute the institution of chattel slavery within the founding of America to the “development and entrenchment of modern anti-Black racial prejudice and ‘scientific’ theories of race” (Blaut 1993, 61–62; Jordon 1968).

The first major investment in transportation systems in the United States, the railroad system, was created to facilitate the transport of Black people—who were considered cargo/chattel, not human beings—in the role of trade and capitalism (Yusoff 2018). The irony of this history is that the railroads used for the movement of goods were built through the labor of enslaved Black people (K. K. Thomas 2011) and later, indentured Chinese migrants (Chang 2019). While the physical movement of Black and Indigenous people was criminalized and punished, Black people and indigenous people were forced to build the infrastructure necessary for what is now known as the United States to move goods and capital for European settlers (Kornweibel 2010). The labor system was structured to inhibit the economic advancement of racialized people.

Source: Created by David Claypool Johnston in 1863, Public Domain, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.182753.html

Cartoon text from Figure 12, which mimics the English nursery rhyme “The House that Jack Built”:

This is the House that Jeff built.

This is the cotton, by rebels call’d king, (Tho’ call’d by loyalists no such thing) That lay in the house that Jeff built.

These are field-chattels that made cotton king, (Tho’ call’d by loyalists no such thing) That lay in the house that Jeff built.

These are the chattels, babes, mothers, and men, To be sold by the head, in the slave pen__ A part of the house that Jeff built.

This is the thing by some call’d a man, Whose trade is to sell all the chattels he can. From yearlings to adults of life’s longest span, In and out of the house that Jeff built.

These are the shackles, for slaves who suppose Their limbs are their own, from fingers to toes; And are prone to believe, say all that you can, That they shouldn’t be sold by that thing call’d a man; Whose trade is to sell all the chattels he can, From yearlings to adults of life’s longest span, In and out of the house that Jeff built.

These buy the slaves, both male and female, And sell their own souls to a boss with a tail Who owns the small soul of that thing call’d a man; Whose trade is to sell all the chattels he can, From yearlings to adults of life’s longest span, In and out of the house that Jeff built.

Here the slave breeder parts with his own flesh To a trader down south, in the heart of the secesh. Thus trader and breeder secure without fail The lasting attachment of him with a tail, Who owns the small soul of that thing call’d a man; Whose trade is to sell all the chattels he can, From yearlings to adults of life’s longest span, In and out of the house that Jeff built.

This is the scourge, by some call’d the cat; Stout in the handle, and nine tails to that: ’Tis joyous to think that the time’s drawing near When the cat will no longer cause chattels to fear, Nor the going, going, gone of that thing call’d a man, Whose trade is to sell all the chattels he can From yearlings to adults of life’s longest span In and out of the house that Jeff built.

Here the slave driver in transport applies, Nine tails to his victim, nor heeds her shrill cries. Alas that a driver with nine tails his own; Should be slave to a driver who owns only one: Albeit he owns that thing call’d a man, Whose trade is to sell all the chattels he can, From yearlings to adults of life’s longest span In and out of the house that Jeff built.

Here’s the arch rebel Jeff whose infamous course Has bro’t rest to the pillow, and made active the hearse; And invoked on his head every patriots curse, Spread ruin, and famine, to stock the slave pen, And furnish employment to that thing among men Whose trade is to sell all the chattels he can, From yearlings to adults of life’s longest span In and out of the house that Jeff built.

But Jeff’s infamous house is doom’d to come down. So says uncle Sam, and so said John Brown. With slave pen, and auction, shackles, driver, and cat, Together with seller, and buyer, and breeder, and that Most loathsome of bipeds by some call’d a man, Whose trade is to sell all the chattels he can, From yearlings to adults of life’s longest span In and out of the house that Jeff built.

4.2 Segregated Work Forces

Prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, racial and gender segregation across workforces was deeply institutionalized throughout the United States (Stainback and Tomaskovic-Devey 2012). Scholars argue that racial hierarchies were reflected in almost every industry and work setting that held racialized people and women, especially Black women, in lower positions and white men in supervisory positions (Stainback and Tomaskovic-Devey 2012). The structural origins of workplaces, unions, and wages aimed to protect the economic interests of whiteness. As a result of slavery and racialization in the United States, racial stereotypes persisted, allowing White employers to categorize racialized laborers as unintelligent, lazy, docile, low-skilled, and generally inferior to White laborers.

In addition to the reinforcement of racial hierarchy, segregated work forces aimed to prevent the economic advancement of Black and Latinx people. The labor associated with the construction of southern railroads was exclusively built by enslaved persons (Jefferson 2019); however, the workforce was integrated in some positions amongst gender and race. Scholar Ted Kornweibel accounts that there were Black enslaved laborers that worked alongside paid white and even Mexican workers (Garcilazo 2012). Kornweibel argues that the assignment of jobs based on what Black people were allowed to do or not allowed to do continued after the Civil War and it was reflected in several workforces soon after (Kornweibel 2002). The following examples illustrate segregation and discrimination of racialized workforces within American history.

Pullman Porters

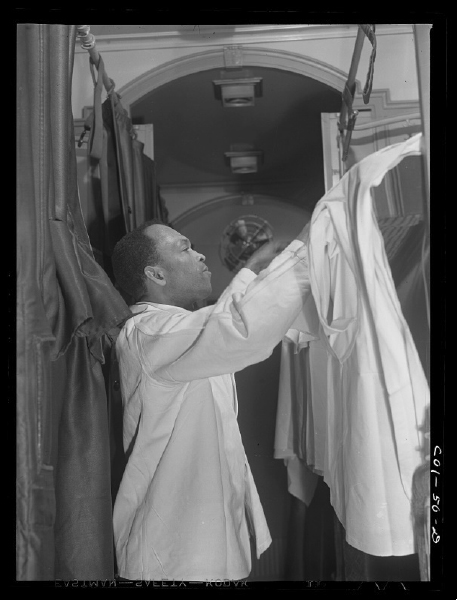

After the Civil War, inventor of the Pullman sleeping car, George M. Pullman hired thousands of Black men to serve White passengers traveling across the country via railroad (see Figure 13). According to Pullman, he specifically recruited and employed Black porters because he believed that formerly enslaved workers would feel comfortable serving White people for extremely low wages. Scholars note that George Pullman held colorist beliefs that Black porters with darker skin were more subservient to white riders (Tye 2005).

Pullman porters are often credited with progressing the Black community in the early 1900s, especially formerly enslaved Black men. The Pullman Company became the largest single employer of Black men in the country. The Pullman Company exploited workers through low wages and perpetuated the indignities and humiliation of overt racism, yet Pullman porters strategically leveraged their experience as railroad workers. The Pullman porters “played important social, political, and economic roles, carrying jazz and blues to outlying areas, forming America’s first Black trade union, and acting as forerunners of the modern Black middle class by virtue of their social position and income” (Tye 2005).

Source: Image published March 1943 by Jack Delano, Public Domain, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017828610/

U.S. Military Force

Racialized men who volunteered for duty or were drafted to the U.S. military faced discrimination and were forced into segregated divisions. Black and Latinx military members were subject to support roles, such as “cook, quartermaster and grave-digging duty” (Gates Jr 2013). During World War II, a Black newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier, released a national campaign called the Double V Campaign which called for the government to end discrimination within the military while urging Black people to contribute to American war efforts. This was referred to as a “battle against enemies from without and within” (Gates Jr 2013).

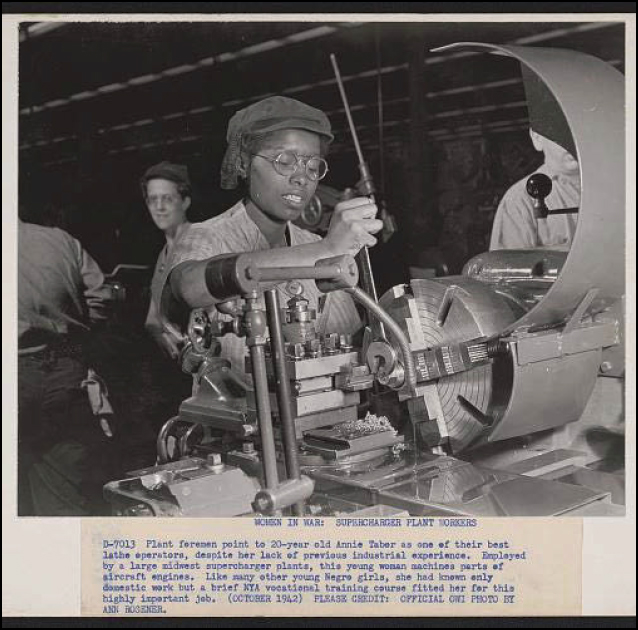

Figure 14 depicts a photograph of a Black woman contributing to aeronautical wartime efforts during World War II. The photograph is accompanied by text that reads, “Plant foremen point to 20-year-old Annie Tabor as one of their best lathe operators, despite her lack of previous industrial experience. Employed by a large Midwest supercharger plant, this young woman machines parts of aircraft engines. Like many other young Negro girls, she had known only domestic work, but a brief National Youth Administration vocational training course fitted her for this highly important job. (October 1942) PLEASE CREDIT: OFFICIAL OWI PHOTO BY ANN ROSENER.”

Source: Image published October 1942 by Ann Roseno, Public Domain, https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.55874/

Panama Canal

When the French initiated construction of the Panama Canal in 1881, they created a payroll system referred to as “gold roll” and “silver roll” to distinguish tiers of pay, benefits, and living amenities, with gold as the higher tier. The gold and silver roll workers included thousands of Black men and women from the United States and from the West Indies and Caribbean islands (P. C. Brown 1997). The United States took control of the project in 1904 and completed the canal in 1914. Under U.S. control, the gold and silver payroll system was quickly solidified as a racial discrimination system similar to Jim Crow. President Taft even initiated the mass demotion of Black gold roll workers to the silver roll (Lydia 2008).

4.3 Mass Incarceration and Criminalization

Racialized people in the United States have experienced a history of legal and social limitations that seek to control or limit movement, behavior, culture, and decision-making (Nicholson and Sheller 2016). These limitations have proven to be harmful and persistent, as they have existed since the era of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and are still prevalent today (Sheller 2018).

Discriminatory laws, policing and incarceration represent the most effective tools for control and exclusion of racialized people (Adams and Rameau 2016; Hawkins and Thomas 2013). Scholars and organizers M. Adams and Max Rameau (2016) describe police, from their origin, as being an “occupying force” established to assert power and social order over racialized people. Scholar Larry H. Spruill (2016) in Slave Patrols, “Packs of Negro Dogs” and Policing Black Communities links contemporary examples

of excessive policing to patrols created in response to slave revolts, and the capture of enslaved Black people (Spruill 2016). The justification of slave owners for the enslavement and subjugation of Black people (like the justification put forth by colonizers of the Manifest Destiny) was that Black people were assumed to be “savages,” “violent,” and “criminal” (Bar-Tal 1990).

In addition to policing, laws at the local, state, and federal levels disproportionately targeted and discriminated against racialized people. As a result, the basis of race determined the differential treatment and harmful outcomes for racialized people (Fellner 2009). Towards the new millennium, Black urban communities were “ghettoized” and faced with poverty, drug addiction, neglect and joblessness (R. J. Sampson and Wilson 2020). John R. Logan and Deirdre Oakley (2017) understand ghettoization as the separation and containment of Black communities through over-policing, housing policies, and infrastructural neglect (Logan and Oakley 2017). As a result of ghettoization, the pressures for governmental institutions to reduce violent crime increased. In 1971, President Nixon declared the “war on drugs” and propelled the justification of more policing (Poveda, 1994), the construction of more prisons (Jensen 2020), and harsher sentencing which caused the prison population to grow (Exum 2021).

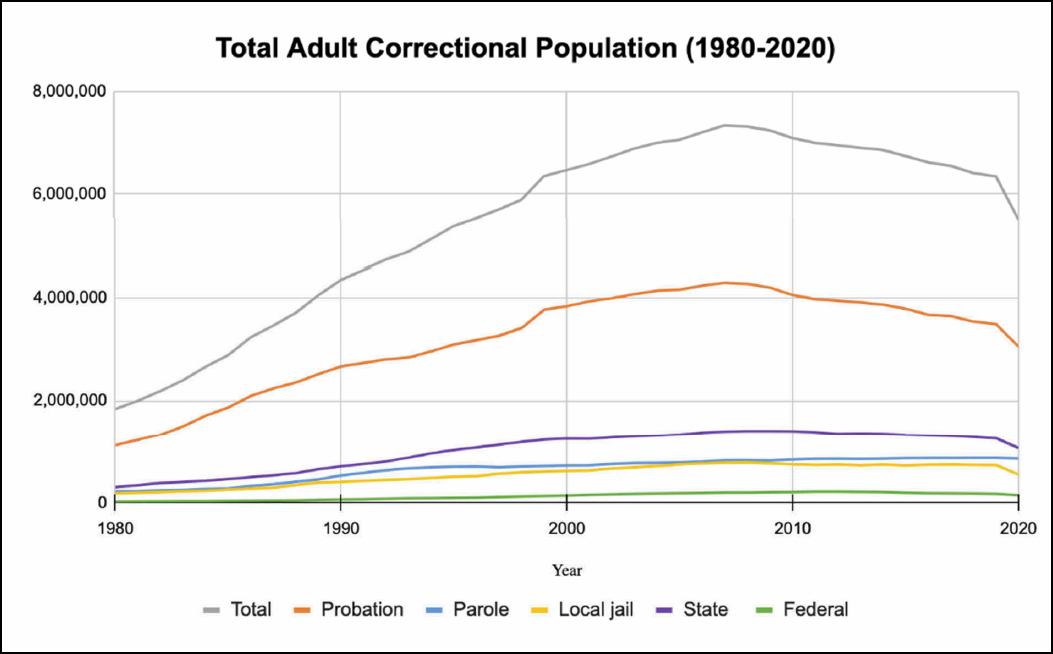

Persistent criminalization of Black people throughout U.S. history provides context for mass incarceration and the current state of the carceral system (Alexander 2012). Mass incarceration is defined by Garland (2001) as “a rate of imprisonment...that is markedly above the historical and comparative norm for societies of this type” (Garland 2001). Figure 15 shows the total U.S. adult corrections population from 1980 to 2020, including local jails, state prisons, federal prisons, adults under parole, and adults under probation (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2022). Since the 1980s, when a war on drugs and crime was politically waged on Black and Brown communities, there has been an approximate 500-percent increase in the total prison population (Nellis 2021). With a corrections population of approximately 2 million people, the United States has the highest imprisonment rate in the world (Sawyer and Wagner 2022). The disproportionate impact of mass incarceration spans all ages as Black youth are over four times as likely to be detained or committed in juvenile facilities as their white peers (Rovner 2021). According to the Sentencing Project, Black people in the United States are incarcerated in state prisons across the country at nearly five times the rate of white people (Nellis 2021). Scholar Michelle Alexander refers to the overwhelming number of African Americans in the carceral system as “the new Jim Crow” (Alexander 2012).

Punitive tactics to enforce laws such as citations, ticketing, probationary periods can cause a “snowball effect” within the criminal legal system (McArdle and Erzen 2001). Within the criminal legal system, one punishment or decision can impact the next, which can result in a continuous and ongoing relationship with the court systems. This snowball effect makes it difficult for racialized people to leave the criminal legal system once they enter it (Sever 2020). The cycle of criminalization occurs when the social stratification of those marked as “criminals” or “felons” struggle to become de-criminalized (Cacho 2012). Scholar Lisa Marie Cacho adds, “to be stereotyped as a criminal is to be misrecognized as someone who committed a crime, but to be criminalized is to be prevented from being law-abiding.” Furthermore, to be criminalized is to be “the object and target of the law, never its authors or addresses” (Cacho 2012).

Source: Data from Bureau of Justice Statistics 2022; chart generated by The Ohio State University

Current transportation systems, protocols, and policies produce harmful and damaging effects on the quality of life for racialized and low-wealth groups. Some of these systems and policies can be characterized as spatial or place-based harm that intentionally and directly impact racialized people (Enright 2019). The relationship between criminalization and transportation is often linked to fare evasion or eating on transit (M. J. Smith and Clarke 2000). The inability to pay for transportation may lead to charges, fines, or even arrests (Menendez et al. 2019). The failure to pay these fines can become a “failure to comply with a court order” charge that can lead to imprisonment.

In summary, the functions of the criminal legal system include laws, policies, courts, fines, citations, police, corrections, reentry, and surveilling technologies (Bryant 2021). These functions have disproportionately impacted the Black and Latinx populations in the United States and maintain cycles of isolation and exclusion (Bryant 2021). Mass incarceration and the prison-industrial complex is a procedural system that aims to detain, arrest, and imprison (Gordon 1999) anyone who is not “white, middle class, secular, gender-conforming, heteronormative, able-bodied, legally employed, state-documented citizen” (Leese and Wittendorp 2017) in the name of public safety (Brewer and Heitzeg 2008). Those who have been criminalized experience challenges such as finding employment (Segall 2011), voting (A. E. Harvey 1994), traveling (Wheelock 2005), obtaining public benefits and housing (Ocen 2012), bearing arms (Gulasekaram 2010), establishing parental rights (D. E. Roberts 2000), and more.

4.4 Legacies of Economic Systems of Racial Capitalism within Aviation

4.4.1 Workforce/Occupational Segregation

A diverse workforce is one necessary component of a strategy that aims to prevent the social biases that invalidate or minimize the knowledge and contributions of people experiencing marginalization and oppression. The lack of diversity is especially stark in the aviation industry, which is socially coded as a career for cisgendered white men (S. M. Morrison and McNair 2022). The number of women who hold the commercial pilot certification in the United States hovers around 4 percent; women still represent less than 5 percent of both maintenance technicians and C-suite roles; and women also represent less than 20 percent of dispatchers, aerospace engineers, airport managers, and air traffic controllers (Lutte 2019). “A complex system of barriers impedes the recruitment, retention, and advancement for women in aviation” and these barriers compound over time (Women in Aviation Advisory Board 2022). A study of women working for European civil aviation firms found that women’s occupations in aviation are frequently oriented around customer service and emotional labor, which derive limited structural power within their employer organizations (G. Harvey, Finniear, and Greedharry 2019).

Drawing and attracting diverse talent to the industry, improving the diversity of the existing workforce, and the general lack of workforce pipeline is an ongoing crisis occurring in the aviation industry (Eby and Lewis 2019). Inflexible eligibility requirements, expensive training, inflated minimum qualifications, and lack of inclusive hiring practices often unnecessarily exclude qualified diverse applicants, and thus stifle diversity in the aviation workforce. For example, as of 2019, the cost of education and flight training was upwards of $150,000, and a private pilot certificate was $9,500 (Eby and Lewis 2019).

The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 created the Youth Access to American Jobs in Aviation Task Force to provide recommendations on expanding the workforce pipeline for careers in aviation, especially for underrepresented groups. The Task Force’s September 2022 report provided recommendations for students to pursue careers in aviation and aerospace through early engagement, information access, collaboration, and funding. Specific recommendations addressing funding challenges and financial hurdles include decreasing the cost of flight training, increasing the maximum amount of educational grant money allowed to be disbursed through Pell Grants offered to students, developing aviation scholarship programs, and implementing workforce development programs (FAA Youth Access to American Jobs in Aviation Task Force 2022). The FAA also offers a Minority Serving Institutions Intern Program for underrepresented students enrolled in undergraduate or graduate school who are interested in working in the aviation industry (FAA 2022).

The aviation industry is working to address workforce and other diversity challenges through various initiatives. For example, ACRP hosted an Insight Event in April 2022 titled Systemic Inequality in the Airport Industry: Exploring the Racial Divide which convened industry practitioners and encouraged candid discussion on many of the aforementioned challenges and strategies for overcoming them (McNair 2023). Event panelists and audience participants shared their perspectives and lived experiences encountering racism, othering, tokenism, and sexism during their aviation careers. Some of the emerging initiatives that participants discussed include but are not limited to rethinking qualification requirements; diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice-oriented workforce initiatives; airport business and supplier diversity programs; and reporting such as corporate social responsibility reports and environment, social, governance reports that encourage accountability and socially responsible investing. The event underscored the need for improved resources and decision-making frameworks on incorporating equity and environmental justice principles into airport decision-making.

4.4.2 Generational Wealth Inequality

Generational wealth and business opportunity inequalities result from the legacies of economic systems of racial capitalism. U.S. Congress enacted the first Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) statutory provision in 1983, which has since been reauthorized and expanded into the current USDOT’s DBE program.

“The Disadvantaged Business Enterprise program is designed to remedy ongoing discrimination and the continuing effects of past discrimination in federally assisted highway, transit, airport, and highway safety financial assistance transportation contracting markets nationwide. The primary remedial goal and objective of the DBE program is to level the playing field by providing small businesses owned and controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals a fair opportunity to compete for federally funded transportation contracts.” (U.S. Department of Transportation 2022b)

The 2022 USDOT Equity Action Plan includes a focus on wealth creation and a goal to increase USDOT direct contract dollars awarded to small, disadvantaged businesses by 20 percent by 2025. The plan outlines the root drivers perpetuating wealth inequalities for small, disadvantaged businesses when seeking to work with the USDOT. Drivers include the following:

- Restrictive procurement practices such as laws, policies, and programs have become inadvertent barriers to new entrants and small disadvantaged businesses. Administrative requirements often serve as barriers to entry for minority-owned business and small disadvantaged businesses.

- Uneven resource distribution results in a lack of access to capital sources (loans, lines of credit, cash advances) for Black and Hispanic-owned businesses, preventing growth. Minority-owned business and small disadvantaged businesses struggle to compete in government contracts due to inadequate bonding capacity and access to surety expertise.

- Limited networks prevent minority-owned businesses and small disadvantaged businesses from industry access, funding, and opportunities (USDOT 2022b).

ACRP’s Guidance for Diversity in Airport Business Contracting and Workforce Programs (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine et al. 2020) suggests potential policies and practices that have been demonstrated to increase diverse business participation at airports. One strategy includes “unbundling” contracts so that large contracts include smaller components or are broken into smaller contracts so that small businesses can bid on them separately. Another strategy includes establishing small business set-asides in which certain contracts require subcontracting opportunities for small businesses. Contract or project-specific diversity goals can also be used to improve opportunities for small businesses, depending on federal and local programs. The guidance suggests that business diversity initiatives and goals should be communicated and incorporated into high level organizational strategic planning and communications. Airports can engage diverse businesses through outreach to create spaces for training, networking, and sharing information. The guidance includes many examples of outreach and training initiatives, along with strategies for monitoring and evaluating performance and communicating accomplishments (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine et al.

2020). Additional guidance from ACRP is available in the Guidebook for Increasing Diverse and Small Business Participation in Airport Business Opportunities (Exstare Federal Services Group, LLC et al. 2015).

4.4.3 Unlivable Wages

Airports offer many types of jobs that span the spectrum from chief executive officer to fast-food cashier. Many of the jobs that airports offer are low-wage occupations, such as baggage handlers, cabin cleaners, and retail workers, often hired through third-party contractors. Outsourcing these positions has enabled airlines to maintain low wages for these occupations, as wages for outsourced workers are usually lower than wages for directly hired workers in the same occupations. Wage growth in air transport related occupations has also lagged behind the average across all industries (Dietz, Hall, and Jacobs 2013). The majority of these low-wage contracted jobs that lack benefits, are held by Black, Latino, and immigrant workers (Beals 2022). In 2022, contracted airline workers held nationwide protests over low wages.

Larger airports tend to be located in metro areas with a high cost of living, posing an additional challenge. Long commutes, the cost of badging, parking or even the cost of daily public transportation combined with low wages can make working at an airport unaffordable (Nadeau 2015). Low-wage jobs can also put a strain on airport staffing as high turnover rates result in a strained capacity to retain experienced workers who can commit to the job. Many low-wage jobs require security clearance and high turnover can add to security concerns. Higher wages and job standards can reduce turnover and create a more stable, experienced workforce (Dietz, Hall, and Jacobs 2013).

Some airports have introduced living wage ordinances to mitigate against the effects of an unstable, inexperienced workforce. One of the first instances was at the San Francisco International Airport in 2000, which established minimum compensation and training standards for airport workers whose jobs impact safety and security. The policy went well beyond screeners to include baggage handlers, cleaners, fuelers, skycaps, customer service agents, and any other workers with access to secure areas of the airport (Dietz, Hall, and Jacobs 2013). Seattle-Tacoma International Airport raised the minimum wage at the airport to $15 per hour in 2014. In 2016, Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority announced a minimum wage of $15 per hour in 2023 (Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority n.d.). The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey announced a $19 per hour living wage in 2023, recognizing that low wages were leading to high turnover rates (The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey 2018).

4.4.4 Airports as Sites of Human Trafficking

Human trafficking, often termed modern-day slavery, is the recruitment, transport, or transfer of persons using force, fraud, or coercion to exploit them for acts of labor or sex. It is the world’s fastest growing criminal enterprise, estimated to be a $32 billion industry, annually. According to the International Labor Organization, 49.6 million individuals globally are trapped in slave-like conditions (International Labour Organization, et al 2022). Human trafficking is the fastest growing organized crime enterprise with approximately $150 billion in annual profits (International Labour Office, n.d.).

The transportation industry plays a vital role in human trafficking. It enables traffickers and their victims to move from place to place, meeting supply and demand, evading law enforcement and removing victims from familiar surroundings (Yagci Sokat 2022). Air transport is one mode of transport used by traffickers and their victims. Just as air transport facilitates movement of people and cargo around the

world, it also facilitates human trafficking. One study on labor trafficking showed that of the 122 victims identified, 71 percent of them had been trafficked by flight (Owens et al. 2014).

The USDOT recognizes that transportation infrastructure facilitates the movement of people through human trafficking channels and has developed a suite of training materials for employees within aviation, rail, and bus transport, along with a public awareness campaign (U.S. Department of Transportation 2022b). The aviation campaign, a collaboration of the USDOT, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and U.S. Customs and Border Protection, is called the Blue Lightning Initiative. This initiative provides training to aviation industry personnel to identify potential traffickers and victims and to report suspicions to federal law enforcement. The FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act of 2016 required air carriers to provide flight attendant training on recognizing and responding to human trafficking victims, and the FAA reauthorization Act of 2018 expanded the training requirement to other “air carrier workers whose jobs require regular interaction with passengers on recognizing and responding to potential human trafficking victims” (U.S. Department of Transportation 2022a).

4.4.5 Affiliations with the Prison-Industrial Complex

Any discussion of social equity within American transportation systems would be incomplete without acknowledgment of the connections to the carceral state and the prison-industrial complex. Airport facilities exist within the larger system of prisoner transport and detention. JPATS had over 92,000 prisoner movements by air in fiscal year 2021 (U.S. Marshals Service 2022). Airports may contain their own holding facilities for temporary holding of incarcerated persons who are being transported and for detainment of traveling passengers (Fiorilli 2019).

Airports are also used to transport immigration detainees. In September 2022, Governor Ron DeSantis, known for his anti-immigrant stance, used taxpayer funds from Florida’s migrant relocation program to fly 48 asylum-seeking migrants from San Antonio, Texas to Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. However, the migrants assert they were misled by officials and unaware that Martha’s Vineyard was their destination. The Florida Department of Transportation paid $1.5 million to Vertol Systems Company Inc., an aviation business based in Florida whose owner is a campaign contributor to DeSantis, to transport the migrants. The legality of DeSantis’ actions remains under investigation for a variety of reasons including allegations that the flights constituted human trafficking and that the aviation services paid in advance to Vertol Systems Company Inc. were not rendered (Morrow 2022; Klas 2022).

Five airports across three states were directly involved in the transport of these migrants (Cunningham 2022). The migrants departed on two aircraft from Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas which is a Department of Defense joint-use facility that operates both military and civilian flights. Both aircraft also stopped briefly at Bob Sikes Airport in Crestview Florida, a general aviation airport self-described as a “haven for defense and industrial aerospace development” (FlyCEW Airport 2022). From Florida, one aircraft made a stop at Charlotte Douglas International Airport in North Carolina, a large hub airport while the other stopped at the Spartanburg Downtown Memorial Airport in South Carolina, a general aviation airport. Both aircraft then departed to Martha’s Vineyard Airport in Massachusetts which is a general aviation airport and the only airport on the island serviced by commercial airlines.

It remains unclear how airports can be legally accountable or legally empowered to intervene to ensure the health and safety of detained passengers transported through their facilities. This example shows that aviation networks can be exploited for political posturing in a manner that causes harm to oppressed and vulnerable men, women, and children.

Airports, as organizations, may also cooperate and financially benefit from the prison-industrial complex. For example, Charlotte City Council members scrutinized an airport contractor, Florida-based company Prison Rehabilitative Industries and Diversified Enterprises (PRIDE), because their company heavily relies on inmate laborers and pays extremely low wages of 20 cents to $1 per hour (Bruno 2021). After a tie-breaking vote by Mayor Vi Lyles, the council ultimately approved the $120,000 contract with PRIDE to supply airfield paint for Charlotte Douglas International Airport. PRIDE produces paint, its paint division encompasses 16 workers, five of whom were formerly incarcerated (Bruno 2021).

Supporters of PRIDE highlight the benefits that PRIDE provides to their transitional workforce of formerly incarcerated persons, but the pathways to be eligible for the transitional workforce require significant time working as a low-wage incarcerated worker. In 2021, PRIDE “provided an average of 1,375 workstations for inmate work assignments that trained 2,525 inmates who worked a total of over 2 million hours” (OPPAGA 2022). After 6 months of incarcerated labor and upon release from prison, incarcerated workers are eligible for PRIDE’s transitional workforce where workers typically earn $15 an hour and receive housing and transportation.