Structural Racism and Inequity in the U.S. Aviation Industry: Foundations and Implications (2024)

Chapter: Systemic Oppression

5. SYSTEMIC OPPRESSION

LEARNING GOALS

This chapter includes three subsections that explain oppression related to mobility, oppression related to place, and legacies of systemic oppression within aviation. This chapter allows the reader to:

- Understand historic regulatory and legal practices that established race-based housing restrictions and criminalized movement and travel of racialized communities.

- Recognize how systemic racism in the transportation sector relates to environmental injustices.

- Link the legacy of white supremacy and harmful outcomes as a result of systemic racism to present-day airport planning and development practices.

INSIGHT WARM-UP

Historical Context

U.S. infrastructure policy has a long history of overtly targeting and harming racialized neighborhoods and low-wealth communities. How do you think the housing and land use policies of the past shaped the opportunity for the airport to operate in its current location? Are you familiar with the local history of redlining or Jim Crow laws that shaped zoning, land use planning and development near the airport?

![]()

Lenses and Ways of Knowing

Oppression is the imposition of power by one group, onto another without consent, without compassion, and without morality. The institutional manifestation of systemic oppression takes place by way of laws, policies, procedural standards, exclusionary eligibility rules, and the inaccessibility of basic economic, health, and quality-of-life needs.

Scholars of mobility justice understand that systemic oppression shapes individual mobility options as well as the larger spatial patterns of place (like infrastructure and residential development). Sociologist Dr. Mimi Sheller provides evidence that the management of mobility post-slavery is rooted in white supremacy ideologies; particularly, social constructions in class, race, sexuality, able-bodiedness, gender, and citizenship.

Present-Day Legacies in Aviation

From the perspective of mobility, consider the systemic oppression of airport passengers, airport customers, and airport visitors. How is mobility racialized and policed at the airport? From the perspective of place, consider the systemic oppression of airport-adjacent residents during the land use planning and development process. How is airport development imposed on local communities and what recourse or deep engagement is available to them?

5. SYSTEMIC OPPRESSION

Systemic oppression is a function of racism and othering that manifests in several ways. Systemic oppression “is the result of three levels working together all the time, reproducing, and influencing each other steadily: (1) the personal/individual, (2) the cultural/ideological, and (3) the structural/institutional level” (Liedauer 2021). Oppression is the imposition of power by one group, onto another without consent, without compassion, and without morality. The processes and decisions through which the imposition occurs often become endemic before those who will most negatively be impacted become privy to them. While oppression is often characterized as being systemic—and it is systemic—those accountable for its outcomes are individual actors within systems. As described by philosophy professor, Dr. Jay Drydyk, “When people contribute to systemic inequalities, they are acting on purpose, but often their purposes are not focused on restricting the choices and advantage of others” (Drydyk 2021). Therefore, there is a dual accountability framing that must be included in any analysis of oppression and its impacts. That is, the widespread patterns of behaviors comprised of individual acts form the basis of systemic oppression. As systemic oppression is endemic, affecting many systems and institutions, the range of people impacted by oppression is vast.

Oppression is a word people hear and immediately think of indisputable cruelty and overtly negative dynamics. In reality, oppression is pervasive and challenging to disrupt because it can function covertly in day-to-day life (some call this civilized oppression), such that individuals may be desensitized to its presence and fail to recognize its influence on societal outcomes. Therefore, oppression must be understood as a web of tactics that entangle those who have been specifically targeted as well as those who encounter the tactics by happenstance. As depicted in Table 2, examples of identity-specific oppression include class and cast structures; racism and the construction of racial identities for the purpose of imposing subordination; and the configuration of space and processes in ways that exclude people with nonconforming bodies and minds. The institutional manifestation of systemic oppression takes place by way of laws, policies, procedural standards, exclusionary eligibility rules, and the inaccessibility of basic economic, health, and quality-of-life needs (Liedauer 2021). Systemic oppression has many manifestations and tactics. In the context of transportation planning (and other land use-related sectors) oppression typically manifests as forms of displacement, exclusion, and confinement.

Table 2. Examples of Social Groups and their Privileged/Oppressed Dimensions

| Social Group | Privileged | Oppressed |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | Female |

| Sexual Orientation | Heterosexual | Homosexual, transsexual, bisexual, pansexual, asexual, queer |

| Class | Middle and upper class | Lower and poor class |

| Race/Ethnicity | European, White | People of Color |

| Religion | Christianity | Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Taoism, Atheism, Rastafari, Judaism, Paganism, etc. |

| Ability | People without impairment | People with impairment |

| Age | Adults (18–65 years) | Children, older adults |

| National Origin | Born in Europe or Northern America | Refugee, immigrant |

| Indigenous Culture | Non-aboriginal | First nation, Inuit, aboriginal, indigenous |

| Mother Tongue | English | Other than English |

| Source: Susanne Liedauer (2021) | ||

5.1 Oppression Related to Mobility

In the book Mobility Justice: The Politics of Movement in an Age of Extremes, scholar Mimi Sheller (2018) argues that the management of mobility post-slavery is a function of social constructionism rooted in white supremacy ideologies; particularly, social constructions in class, race, sexuality, able-bodied, gender, and citizenship. Sheller says, “It is not just that societies based on white supremacy happen to police Black, Latinx, Asian, and indigenous bodies, and various migrant ‘others,’ but that this constant policing of racial, gender, and sexual boundaries and mobilities is fundamental to the founding of white power through the construction and empowerment of a specifically mobile white, hetero-masculine, national subject” (Sheller 2018). In summary, the tools of whiteness seek to control the existence and mobility of racialized people. Despite these tools and relentless attempts to limit their freedom, racialized people have resisted through protests and social movements.

5.1.1 Criminalization of Movement/Freedom of Black and Indigenous Persons

In the United States, the movement of Black and Indigenous bodies has long-been in contention. Whiteness has historically heralded, through social construction, as an aspirational identity and cultural norm. The interests of whiteness aided in the enslavement, criminalization, and demobilization of racialized people which allowed these limitations on mobility to occur. White institutions have often utilized violence, aggressive policing, displacement, and even death to limit the mobility of Black and Indigenous people. The violent tactics that control mobility can be linked from the Trans-Atlantic slave trade to the Trail of Tears, the Bloody Sunday in Selma, and the murder of Ahmaud Arbery in 2020. Political leaders and activists have expressed frustrations for decades as oppression has persisted over time. Historian Rod Clare summarizes this frustration when inquiring “where can Black people go and when can they go there?” (Clare 2016).

In the 19th century, White settlers placed high value on indigenous land, particularly in the southern states, which posed a grievous threat to native tribes. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, through which the Federal Government imposed a power to force indigenous people off of their land in exchange for land in the west (Cave 2003). By 1842, Presidents Jackson and Van Buren had forcibly removed what remained of the Choctaw, Seminoles, and Cherokee tribes to Oklahoma along the now infamous Trail of Tears (Stewart 2007). Furthermore, the indigenous population was directly harmed by decisions made by the Federal Government in the construction of the railroad system.

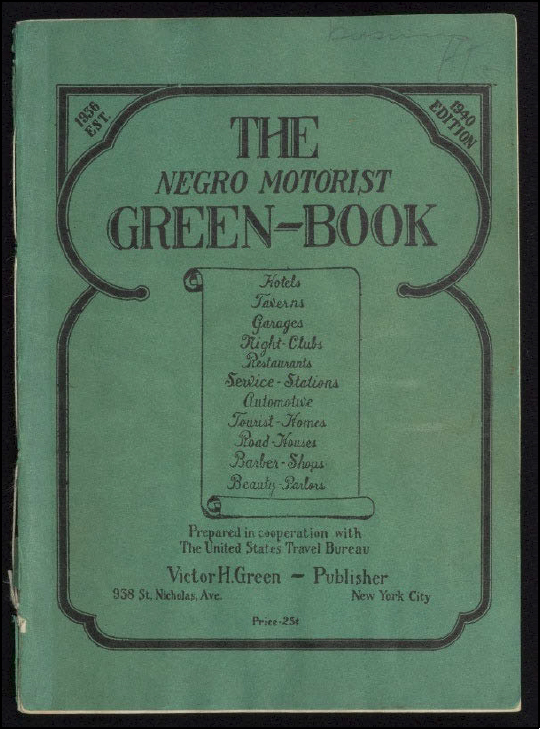

Post Trans-Atlantic slave trade (during the Jim Crow Era), laws were created that aimed to control Black mobility and transportation use in the South (Lüthi 2016). Promptly after the passage of the 13th Amendment and the procedural abolishment of chattel slavery in 1865, Jim Crow laws were introduced to limit the freedom and movement of Black people in the United States. Jim Crow laws segregated workforces at job sites (Roback 1984), criminalized interracial relationships and marriages (Oh 2005), mandated segregated medical care (J. Ward 2010; Kernahan 2021), segregated and enforced substandard care in medical facilities (Nuriddin 2019; K. K. Thomas 2011), and established a set of behavioral codes which limited the expression and autonomy of Black people (Ritterhouse 2006; Guffey 2012). In response to the Jim Crow laws, the Negro Motorist Green Book was published by Victor Green as a guide for Black people (see Figure 16); it identified the businesses that allowed Black patrons throughout the United States (Green 1936). The Green Book was one of the many ways Black people adapted to constraints of mobility and movement that were pervasive during Jim Crow and thereafter. The annually published directory listed businesses that would serve Black travelers. As listed on the

cover, businesses included hotels, taverns, garages, nightclubs, restaurants, service stations, automotive, tourist homes, roadhouses, barbershops, and beauty parlors.

Source: New York Public Library, Public Domain, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/dc858e50-83d3-0132-2266-58d385a7b928

The history of laws pertaining to Black mobility throughout U.S. history can be characterized by the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court case (Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537). During and after Reconstruction, to escape the Jim Crow South, Black people began to migrate to the north to escape the Jim Crow South (Marks 1985). In Louisiana, the legacy of slavery and white supremacist ideologies legitimized a “separate but equal” Supreme Court ruling that dehumanized Black people in the United States and reinforced social hierarchy (Lipsitz 2015). The Separate Car Act segregated railway cars by race for Black riders and white riders (Medley 2012).

In 1892, Homer Plessy, a multi-racial Black man, agreed to challenge the Act and sit in a “whites-only” car of a Louisiana train (Brenman 2007). When Plessy was told to vacate the whites-only car, he refused and was arrested. At trial, Plessy’s lawyers argued that his arrest violated the 13th and 14th Amendments (Johnson 2018). The judge, Associate Justice Henry Billings Brown ruled in favor of state courts and found that Louisiana did not act unlawfully, and Plessy was convicted (Medley 2012). Judge Brown concluded that “the object of the [14th] amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either” (U.S. Supreme Court 1896). In other

words, the 14th Amendment promotes equal protection when it comes to matters of law, but the 14th amendment did not intend to abolish the distinctions between races that render one race inferior to another within the broader context of society.

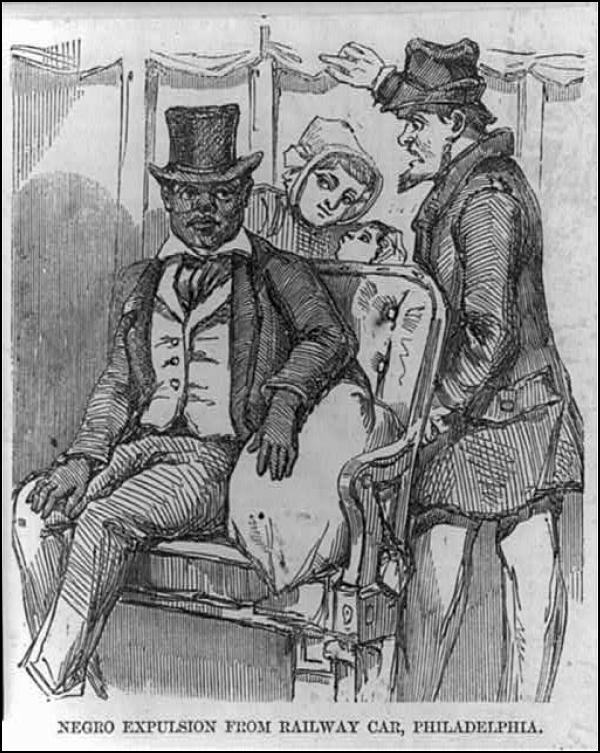

Figure 17 displays an illustration that depicts a well-dressed Black man seated in a railcar. A White railcar worker hovers over him indicating he needs to leave. A White woman and small child watch the scene while seated behind the Black man.

The Plessy v. Ferguson ruling validated the segregation of all modes of public transportation in the South. From 1865 to 1967, there were “more than four hundred state laws, constitutional amendments, and city ordinances legalizing segregation” (Brenman 2007). There were even laws that prohibited the transport of hearses from carrying Black people after death (Brenman 2007). The Plessy v. Ferguson decision laid the groundwork for utilizing laws and courts to limit the movement of Black people and other racialized people. The fight for mobility justice and civil rights within transportation continued into the latter half of the 1900s with the Freedom Riders and the Montgomery Bus Boycott (Alderman, Kingsbury, and Dwyer 2013; Bullard, Johnson, and Torres 2004).

Source: Published in the Illustrated London News on September 27, 1856 Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3a45884/

5.1.2 Structural Racism, Racial Profiling and Discrimination

Structural racism describes the culturally engrained values of society which perpetually re-construct race and race-based interactions. The social values are so widely imposed that many believe race is a fixed reality reflecting “the way things are.” Structural racism is distinct from systemic racism as systemic racism addresses the institutions and processes which rely on racism. Structural racism refers to the historical, cultural, institutional and interpersonal disparities that racialized people face within society (Lawrence and Keleher 2004). In the United States, these disparities have routinely benefited whites and their access to better treatment, privilege, and power.

The advantageous positionality of White people due to structural racism produces harmful outcomes for racialized people. The continuity of structural racism can be attributed to the racial profiling and discrimination within historical, cultural, institutional, and interpersonal practices. Racial discrimination focuses on the difference in one’s skin color, hair, clothing/style, dialect/accent, music, food, smell, facial features, position, class, positionality, education, etc. (W. D. Greene 2008; M. M. Smith 2006). Examples of structural racism within cultural practices can be found in biased news media (Ross and Leigh 2000), film/television (Deo et al. 2008), academia (Gray et al. 2020) and art (K. Torres 2022) and have been linked to the perpetuation of racial stereotypes for educational, comedic, or entertainment purposes (Salter, Adams, and Perez 2018).

Structural racism is often upheld, legitimized, and protected by institutions (Lawrence and Keleher 2004). Several institutions in the United States have documented instances of racial profiling that resulted in harmful outcomes (Utsey et al. 2000). For instance, law enforcement provides high-profile examples of institutional policies and practices that have led to disproportionate rates of racial profiling in the 20th and 21st centuries and mass incarceration for Black and Latinx people (Mauer 2011). Racial profiling has resulted in the extreme surveillance, discrimination, harassment, detainment, arrest, and even death of racialized people (Bass 2001). Furthermore, structural racism speaks to the ways inequalities have been “produced and reproduced within the structures of the U.S. criminal legal system” (Rucker and Richeson 2021). Although many “legal” forms of racial discrimination were overturned through the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, racialized people still experience discrimination in their daily lives today (Sellers and Shelton 2003).

Stop-and-frisk policing has been noted as one the most explicit examples of racial profiling and discrimination within law enforcement practices. In 2013, a federal court found the New York City Police Department’s stop-and-frisk policies to be unconstitutional. Stop-and-frisk refers to the common policing tactic that employs law enforcement to identify, stop and physically search a “suspect’s” body based on “reasonable suspicion” (Meares 2014). Modern policing strategies like stop-and-frisk can be closely traced to the “Broken Windows” theory (1982) that criminalized “visible signs of disorder” like graffiti, loitering, and panhandling (J. Q. Wilson and Kelling 1982). These tactics intend to reduce violent crime but fail to consider disproportionate targeting and harming of racialized people. In New York, data showed that stop-and-frisk policing disproportionately impacted Black and Latinx communities; from 2002 to 2013, police officers stopped and questioned people perceived by the New Work Police Department as engaging in “criminal activity” more than 5 million times (Southall and Gold 2019).

The daily lived experiences of racialized people resulting from structural racism exposes implicit biases and stereotypes. Social movements driven by racialized experiences like “Driving while Black” (Harris 1999) or “Traveling while Brown” (Considine 2017) shed light on the many ways racialized people are consistently profiled, targeted and surveilled in their daily lives, even while using transportation. The podcast, Arrested Mobility (hosted by the founder and CEO of Equitable Cities LLC, Charles T. Brown)

provides in-depth, contemporary examples that illustrate the disproportionate and overly aggressive police enforcement and brutality that Black Americans and other people of color face while walking, running, riding bicycles, taking public transit, or while driving.

5.2 Oppression Related to Place

5.2.1 Race, Space, and Equity: 20th Century Residential Segregation

Infrastructure policy in the United States has a long history of overtly targeting and harming racialized neighborhoods and low-wealth communities. For example, a prosperous Black community called Seneca Village was removed in 1857 to build a portion of New York City’s Central Park, one of the oldest public parks in the United States (Wall, Rothschild, and Copeland 2008). The endeavor to expand and build public works-related infrastructure during the City Beautiful Movement in the early 20th century led to the demolition of low-wealth communities in many American cities (Foglesong 1986). The City Beautiful Movement was a planning and architectural movement emerging from the creation of the White City at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. The movement led to the planning and creation of grand civic and park spaces whose neoclassical aesthetics and new technology were predicted to inspire civic virtue in the populace of cities. The movement led to the demolition of many urban tenement neighborhoods in the process of implementation and the original White City at the Chicago World’s Fair barred most participation by African Americans.

Scholars, such as James Baldwin, note that mid-20th century policies such as urban renewal, public housing, and highway expansion eventually became mechanisms of “negro removal.” Legacies of inequitable systems continue to influence infrastructure projects today as projects are situated within the existing patterns of racial segregation, spatial inequities, and racialized geographies found throughout the United States. Section 6.1 provides a more expansive discussion of racialized geographies.

Racism, anti-immigrant nativism, and religious discrimination (particularly anti-Semitism) all intersected with early 20th century policies of residential segregation. Segregation and institutionalized disinvestment (such as redlining, see Section 5.2.5) are harmful because they isolate racialized and othered groups from economic opportunities. The legacy of structural racism in the housing market and built environment manifests as ongoing depressed wealth for Black people in the United States (Conley 2010; Shapiro 2005; McIntosh et al. 2020; Mitchell and Franco 2018). Further, this form of structural racism in the built environment is known to be detrimental to community and environmental conditions (An, Orlando, and Rodnyansky 2019). Historic patterns of redlining were associated with increased risk for predatory lending practices and resulting foreclosures experienced during the 2008 housing crisis (Jesus Hernandez 2009). Furthermore, public health studies indicate that historic redlining is linked to contemporary health outcomes (McClure et al. 2019), elevated exposure to unhealthy extreme heat events (B. Wilson 2020), and inequities in access to green space (Nardone et al. 2021). Redlining has been empirically linked to contemporary poor health outcomes such as preterm birth (Krieger, Van Wye, et al. 2020), cancer (Krieger, Wright, et al. 2020), and infant mortality (Reece 2021).

Historian Carl Nightingale (2012) called attention to narratives that framed residential segregation as a market-driven inevitability or a neutral manifestation of choice. Nightingale asserted that, to the contrary, the phenomena of residential segregation requires “institutionally organized human intentionality” (Nightingale 2012, 7). Historians and scholars have documented a systemic pattern of inequitable policies and practices throughout the 20th century, by both the private and public sector,

that enforced segregation upon housing markets, particularly in metropolitan areas (Reece 2021). As Richard Rothstein (2017) documents in The Color of Law, the interwoven and reinforcing nature of private sector and public sector segregation is a manifestation of structural racism in 20th century housing markets and cities that has never truly been remedied.

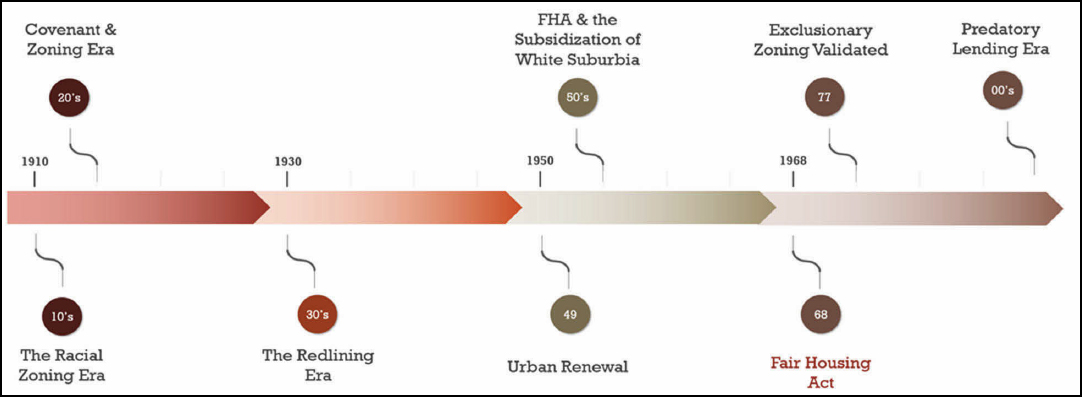

Figure 18 depicts an historical timeline of structural racism in 20th century United States development policy. The United States’ first federal act to dismantle housing segregation (the 1968 Fair Housing Act) follows 60 years of pro-segregation policies. The Supreme Court’s decision in Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Development Corp (1978) would make it difficult to legally challenge facially race-neutral exclusionary zoning ordinances without evidence of direct racially discriminatory intent.

Source: Jason Reece, The Ohio State University

5.2.2 Racial Exclusion & Early Zoning Practices

In the early 20th century, zoning served as one of the primary tools to disinvest from low-wealth neighborhoods and racially segregate housing. Zoning enables regulation of density and provides for control of land use and potential nuisances. Zoning intended to remedy many of the significant health risks associated with early 20th century urbanization, such as overcrowding and exposure to potentially hazardous land uses (Peterson 2003). Zoning practices were first implemented in Germany in the late 19th century and were introduced within the United States in the early 1900s. Whereas German zoning ordinances promoted mixing land uses and housing for different socioeconomic classes, United States zoning focused on land use separation and social control through segregation of various population groups (Richards 1982; Von Hoffman 2009).

Racial zoning was motivated by racist beliefs that racial integration within neighborhoods was a threat to public health, safety, and welfare. For example, racist and pro-segregation officials promoted redlining as a means of preventing the spread of disease, interracial marriage, and miscegenation (Nightingale 2006). Racial zoning was first implemented in Baltimore in 1910 and quickly spread to other cities throughout the United States, particularly in the Mid-Atlantic and South. The practice was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court as unconstitutional in the 1917 Buchanan v. Warley decision. However, policies and practices evolved to utilize facially race-neutral zoning (emphasizing class-based restrictions, e.g., barring rental housing or multifamily housing from new suburbs), comprehensive planning, and restrictive covenants to continue to sustain the effects of racial segregation (Silver 1991).

5.2.3 Racially Restrictive Covenants

After the 1917 U.S. Supreme Court Buchanan v. Warley decision prohibited the use of racial zoning, local city governments and the real estate sector turned to restrictive covenants to prevent racialized people from accessing housing options near White people. Restrictive covenants are a form of deed restriction which prohibited the sale of property to, or occupancy of property by, several racial and ethnic groups. These restrictions either required occupancy by, or sale to, the “Caucasian” or “white race” or specifically prohibited sales to or occupancy by African Americans, Asian or Latinx Americans, Jewish people and racialized immigrants. Deed restrictions were often placed on new residential subdivisions and early suburbs in U.S. urban areas (Gotham 2000).

Restrictive covenants were upheld, propagated, and enforced by both the public and private sector. The U.S. Supreme Court had an opportunity to strike down restrictive covenants as unconstitutional in the 1926 Corrigan v. Buckley decision. The court interpreted covenants as private contracts and therefore not under the jurisdiction of the court. Scholars have identified the Corrigan v. Buckley case critical to the rapid growth and expansion of covenants across the nation (Jones-Correa 2000).

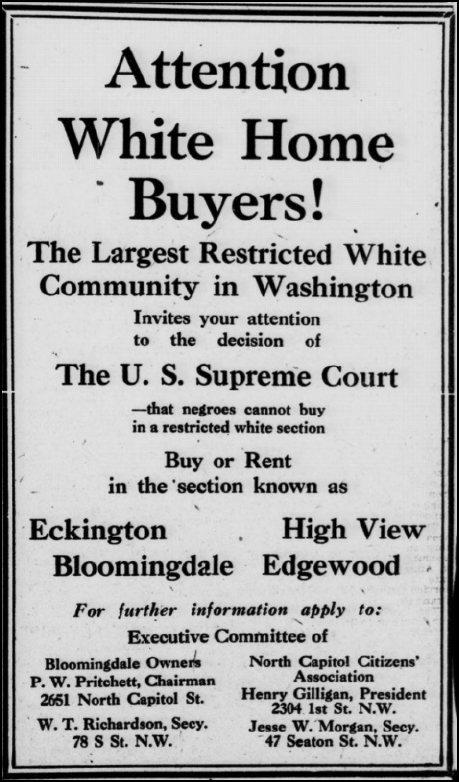

Real estate developers contributed to the proliferation of covenants by attaching them to new residential subdivisions and then using them as a marketing tool to assure white homebuyers that their properties would remain segregated (Burgess 1994; Glotzer 2015). Further, the real estate industry announced the Corrigan v. Buckley decision in marketing materials to reassure White homebuyers that covenants would continue to be enforced (see

Figure 19). The relatively young National Association of Realtors (at the time, referred to as the National Association of Real Estate Boards) included pro-segregation language in realtor training materials and in the organization’s code of ethics. The association’s 1924 code of ethics stated, “A Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood” (National Association of Real Estate Boards 1924).

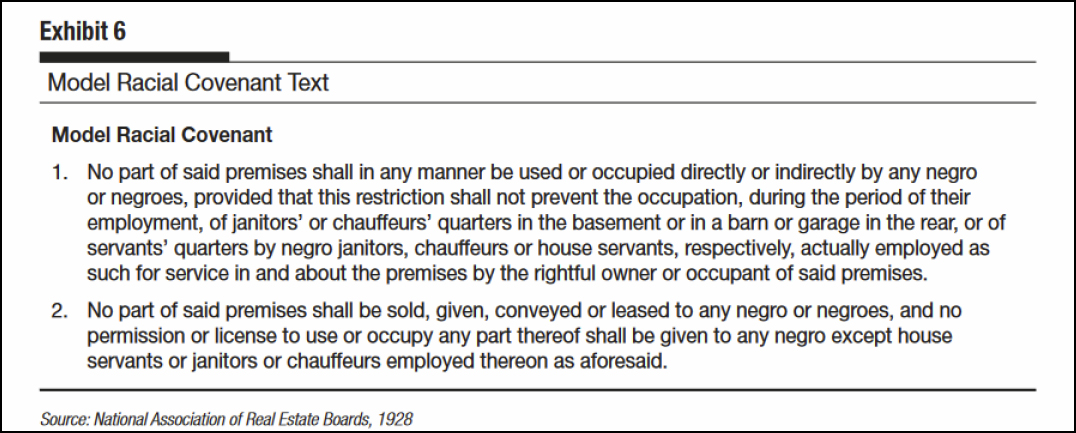

The National Association of Realtors further propagated covenants through their development of model language for racially restrictive covenants in 1928 (see Figure 20). Predatory real estate practices, such as manipulative blockbusting (where realtors would use fear of neighborhood racial change to spur real estate sales), further heightened the pace of segregation in urban areas (Gotham 2002).

Source: Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1926-05-30/ed-1/seq-3/

Source: Santucci 2020

5.2.4 Exclusionary and Expulsive Zoning

Although racial zoning was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1917 Buchanan v. Warley decision, facially race-neutral zoning was still used to heighten patterns of segregation and to harm racialized and ethnic neighborhoods (Whittemore 2017a). Zoning could still exclude people based on class by placing restrictions on higher density housing, multifamily housing or rental housing—housing types typically relegated to racialized people. Further, expulsive zoning practices targeted the placement of noxious land uses into low-wealth and racialized neighborhoods. Expulsive zoning practices tended to de-industrialize White neighborhoods while industrializing racialized neighborhoods, frequently leading to the concentrated disruption and destabilization of Black communities. This practice deteriorates neighborhood conditions, creates environmental hazards, and lowers property values for homeowners. Consequently, expulsive zoning practice has been identified as a primary driver of contemporary environmental justice challenges in racially segregated urban neighborhoods (Whittemore 2017b).

5.2.5 Real Estate Assessment and Racism – The Era of Redlining Emerges

Racially restrictive covenants, real estate practices, and zoning restrictions established an institutionalized pattern of residential segregation. By the 1930s, redlining practices and housing policies that emerged from New Deal housing policies further institutionalized place-based oppression. For example, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), an agency created in response to escalating foreclosures during the Great Depression, played a critical role in the early 1930s housing market through refinancing home loans. By 1935, HOLC held nearly one-fifth of all mortgage debt for family residential properties in the United States (Faber 2020).

As part of their home loan management strategy, HOLC created real estate risk assessment maps throughout the 1930s. These maps greatly influenced city planning and resulted in structural inequities and segregation that continue to exist today. HOLC risk assessment maps created four rating tiers. Properties rated as Grades A and B were generally deemed safe for investment; whereas properties rated as Grades C and D were considered unsafe or hazardous for investment. The color red was used to denote “hazardous” conditions in D-rated neighborhoods, resulting in the origin of the term redlining. Although the term redlining originated as a result of HOLC’s risk assessment maps, redlining is currently used to refer to the practice of strategic disinvestment targeted to racially segregated neighborhoods, particularly neighborhoods predominantly inhabited by Black people.

HOLC ratings were clearly driven by racial animus and influenced the Federal Housing Administration’s (FHA’s) chief economist Homer Hoyt’s theories of racial hierarchy in real estate valuation (Hoyt would serve as chief economist for FHA from 1934 to 1940.) Hoyt created a ten-level ranking of racial and ethnic groups based on their purported positive or negative influence on neighborhood conditions and property values. Hoyt used the following labels and rankings such that a larger numeric value correlated with those he deemed as most detrimental to real estate values: “1. English, Scotch, Irish, Scandinavians, 2. North Italians, 3. Bohemians or Czechs, 4. Poles, 5. Lithuanians, 6. Greeks, 7. Russians, Jews (lower class), 8. South Italians, 9. Negroes, 10. Mexicans” (Squires 2018).

Hoyt’s discriminatory hierarchy had a deep influence on policies and practices at FHA. The influence of theories of white supremacy in real estate are evident in the structure of the assessment notes. Within assessment documents, specific data entry fields were allocated for identifying threats of “infiltration” by detrimental populations. Additionally, the assessor notes were riddled with direct references to racial animus and racially, ethnically, and religiously derogatory statements and slurs. The following

statements are examples of racially derogatory language commonly found in assessments for 12 cities assessed by HOLC in Ohio (Reece 2019):

-

Statements Warning of Potential for Infiltration of “Undesirable Groups”

- practically free from foreign encroachment with the exception of a few Danish families.” - Cleveland

- Although no colored people live in this area, several colored children attended Hawthorn School.” - Cleveland

- Slavish Catholic Church just out of the area at the northwest may have tendency to concentrate Slavish” - Warren

- A very strong effort has been maintained to limit the inhabitants of this area to white only ... although approximately 10negro families are located in the northernmost section along E. 33rd.” - Cleveland

-

Identification of Racially “Undesirable Groups” as Justification for Restricting loan Access to Neighborhood

- Four negro families on Columbus Ave.” -Akron

- Negroes constitute 5% of community.” - Canton

- rapidly being run down through influx of colored and low-income group of whites.” - Toledo

- Very poor class of white intermingling with negro.” - Dayton

- This is a colored section - lower class Jews and Italians.” - Canton

-

Identification of Ethnic/Religious “Undesirable Groups” as Justification for Restricting Loan Access to Neighborhood

- Poles, Slavs, and Russians comprise about 80% of the area’s residents.” - Cleveland

- Foreigners likely to invade this area.” - Warren

- Mixture of low class foreigners - Polish, Russian, Hungarian and negro.” - Dayton

- heavily populated by low class Jews” - Akron

- probability of continued Jewish infiltration may have detrimental effect.”- Cleveland

5.2.6 From Redlining to Urban Renewal and Segregated Suburbs

Although HOLC was a relatively short-lived entity, operating from 1933 to 1954, their maps influenced other federal programs. As described by New York University Professor of Public Policy Jacob Faber (2020), “the historical record documents that HOLC’s practices of racial exclusion were adopted by subsequent federal programs [the FHA’s and GI Bill], which were larger and more durable.” HOLC maps were not officially published, but they were shared with the FHA and were likely used to influence local lenders, local governments, and planners. As described by Faber (2020), “Thus, what HOLC ostensibly intended to be a short-term intervention may have resulted in quite a “strong” institutional mechanism due to its diffusion through and adoption by long-term programs, with dramatic implications for segregation over subsequent decades.”

Redlining of urban neighborhoods produced decades of divestment as FHA guidelines mandated racial separation of “inharmonious racial or nationality groups” in the rapidly growing post World War II (WWII) suburbs (Tillotson 2014). Although the United States experienced a housing development boom of suburban growth in the mid-20th century after WWII, Black people had limited housing options. Black

people were mostly barred from accessing new housing due to exclusionary zoning (which would not allow rental housing) and they were unable to purchase homes due to openly discriminatory underwriting policies, leaving them with few options. Post WWII public housing policies created a more intense form of segregation and unprecedented concentrated poverty.

Post-war policies, such as urban renewal (established in the Housing Act of 1949) and the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, further damaged redlined neighborhoods causing widespread disruption and displacement (Bullard, Johnson, and Torres 2004). Urban renewal programs disproportionately displaced Black and Latinx families (Digital Scholarship Lab 2022). Urban highway construction created further displacement as highway projects were often sited in or through formerly redlined neighborhoods (Karas 2015). FHA guidelines also influenced exclusionary zoning by placing emphasis on the land use characteristics of single-family suburban development in the agency’s site standards (Whittemore 2013). Many high-rise public housing sites never managed to sustainably finance their operations, resulting in dehumanizing and unsafe housing conditions (Bristol 1991). Black veterans were also less likely to benefit from the GI Bill, limiting another potential pathway to homeownership (Woods 2013). Barred from access to the nation’s rapidly expanding suburbs, racialized people were relegated to redlined neighborhoods, experiencing substantial disinvestment (Reece 2018).

5.2.7 Civil Rights Reforms & the Persistence of Housing Discrimination

The Civil Rights Movement challenged discriminatory housing and development policies throughout the 20th century through litigation and organized protest. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and later the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, played a role in legally challenging racial zoning and restrictive covenants (Vose 1954). Organized community groups and coalitions challenged the damage inflicted by federal highway policies in the highway revolts of the 1960s and 1970s. These efforts would ultimately contribute political pressure to federal reforms such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which requires assessment of the environmental impacts of federally funded infrastructure projects. As a byproduct of backlash to urban renewal and other policies, city planning practice eventually embraced mechanisms of community engagement and advocacy on behalf of unrepresented communities (Reece 2018). Dr. Martin Luther King’s Open Housing Movement challenged discriminatory housing policies in northern cities, most notably in Chicago, Illinois. The Open Housing Movement (sometimes referred to as the Chicago Freedom Movement), brought Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s organizing efforts to the City of Chicago in the mid-1960s to protest the forms of discrimination in housing and urban development policies in Chicago and other northern cities. The Open Housing Movement was the largest Civil Rights Movement active in the northern states during the 1960s and is directly attributed to the passage of the national Fair Housing Act in 1968. In the aftermath of Dr. King’s assassination, the landmark civil rights legislation, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (also known as the Fair Housing Act), passed Congress after languishing for years. It was the first comprehensive federal act intended to support open housing markets (Powell and Reece 2009).

Discrimination in housing persists due to evolving policies and practices that continue to reinforce it (Cashin 2004). Although racially restrictive covenants were legally no longer enforceable after the 1948 Shelley v. Kramer U.S. Supreme Court decision, the real estate industry and neighborhood associations widely resisted efforts of integration (using tactics of harassment and discrimination) until the passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act. The federal Fair Housing Act was effective at reducing private discrimination in the market but was unable to counter exclusionary zoning practices. Exclusionary housing and land use policies impede the supply of affordable—and sometimes moderate—income

housing in affluent metropolitan suburbs and exurbs (S. Greene and Ellen 2020). Source-of-income discrimination, where landlords refuse to rent to housing voucher holders, also creates barriers to housing access for renters who utilize federal housing assistance (Tighe, Hatch, and Mead 2017) as market-driven urban redevelopment, which has grown substantially in the past two decades, is dominated by higher priced or luxury housing and in some cases is spurring displacement of long-term residents (Immergluck and Balan 2018). Compounding the crisis, stagnation in wages for low to middle income workers has created tremendous vulnerability to displacement in the real estate market (Chapple 2017).

5.3 Legacies of Systemic Oppression within Aviation

5.3.1 Racial Segregation of Airport Customers

The tradition of restricted movement and racist transportation outcomes stemming from the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, the institution of chattel slavery in the United States, and Jim Crow laws, invokes an interrogation of racism as both a policy framework and as a social dynamic. In Jim Crow Terminals, Anke Ortlepp specifically documents the racial history of airport facilities that, as with other transportation modes, contributed to racial segregation, dehumanization, and trauma.

“[This study] looks at airports as racially coded geographies of mobility and consumption and scrutinizes the ways in which their spatial ordering and material fabric affected both Black and white Americans. It conceives of aviation as a spatial apparatus that not only reflected racism but also created a modernized version of racial discrimination as a southern way of life. This way of life came under attack in the post-war decades when the Civil Rights Movement questioned ideologies of race and also claimed and repurposed the (segregated) spaces that gave built expression to these ideologies.” (Ortlepp 2017, 11)

While the Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938 prohibited air carriers from discriminating against airline passengers on the basis of racial background, municipally owned airports were overt in their discriminatory policies and practices. From the 1940s to the 1960s, airports were particularly hostile toward racialized people: barring them from using the restroom and certain terminal dining establishments, segregating seating and waiting areas, and demolishing Black communities for the construction of airport terminals. These discriminatory practices were most pervasive in the South but were present across the United States varying “from place to place even with states, reflecting the local character of the legal landscape…and sometimes airport managers made the rules” (Ortlepp 2017, 26).

5.3.2 Power and Advocacy

Systemic oppression has resulted in both economic and social generational wealth inequities, including a lack of political power and resources. This has led to environmental justice issues in communities surrounding some airports, such as disproportionate air quality and noise impacts. For example, a study of noise pollution in the United States showed inequitable spatial distribution based on socioeconomic factors. Generally, both daytime and nighttime modeled noise levels were higher for census block

groups with higher proportions of nonwhite residents and residents of lower socioeconomic status (Casey et al. 2017). In contrast, a study of the sociodemographic patterns of exposure to civil aircraft noise across a sample of 90 airports in the United States showed considerable variability among airports. The study reinforced the findings of prior studies and showed that noise exposure patterns cannot be generalized across the country, but rather should be considered on a local scale (Simon et al. 2022). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) notes the following:

“The disparities in environmental burdens and economic benefits disproportionately affect low-income communities and communities of color and can also be exacerbated by long-term disinvestment and challenging socioeconomic conditions. For example…residents of near-port communities in Savannah, Georgia, and Houston, Texas, are predominately people of color and predominantly have below median household incomes. These communities often lack access to the time, resources, technical knowledge and political capital needed to address issues of concern.” (U.S. EPA 2020)

Without access to resources and capacity to organize, these communities are often left out of infrastructure development and planning processes that affect their lives.

The Biden Administration has instituted several federal policies designed to address inequities and help overcome these barriers, including the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) as described in Section 5.3.8. The BIL provides historic funding opportunities for infrastructure in under-resourced communities but recognizes that these communities also require tools to access and deploy that funding. Several federal technical assistance programs for transportation projects exist for state, local, and tribal governments to take advantage of the historic funding opportunities (the White House 2022). One example is USDOT’s Thriving Communities Program which launched in 2022 to provide technical support for teams of community partners to navigate federal requirements, identify funding opportunities, and increase capacity (USDOT 2022c).

5.3.3 Airport Siting and Land Acquisition

Although focused on marine ports, EPA’s Environmental Justice Primer for Ports: The Good Neighbor Guide to Building Partnerships and Social Equity with Communities acknowledges that “While near-port communities may often experience direct or indirect impacts from port activities, many disproportionate impacts on near-port communities are the result of long-term policy and siting decisions across various levels of decision-making.” (U.S. EPA 2020)

George Bush Intercontinental Airport (IAH) in Houston provides one example of harm caused through citing decisions and policies. IAH is one of seven major hub airports opened post-1960 in the United States. In 1965, Houston annexed a small, primarily Black, and impoverished subdivision called Bordersville to construct IAH. Despite promises of city services in exchange for supporting the annexation and development of the airport, Bordersville residents did not receive city water service until 1982 nor sewer service until 1997 (Zuniga 1998; Sallee 1996). In a study of airport-adjacent community demographics, the community near IAH showed a proportional increase in the Black population from 13 percent in 1970 to 35 percent in 2010 (Woodburn 2017). This failure to honor agreements for decades likely had a negative effect on home values, resulting in lasting effects on

generational wealth for Black families in the area. In 2001, city officials named Bordersville as part of the IAH/Airport Super Neighborhood Council, a group specifically “aimed at bringing much-needed improvements to the long-neglected community” (Stanton 2001). While this council is arguably not fully restorative or reparative, it is a strategy for confronting past racial harms and reorienting priorities and power structures in the airport siting and land acquisition process.

5.3.4 Lack of Equitable/Deep Community Engagement

All work to make transportation more equitable and accessible should be based on a foundational understanding of the history of civil rights and mobility justice in the United States. A common understanding ensures recommendations and strategies are contextually appropriate and prevent further harm. As airports collaborate with community stakeholders, they need to understand how transportation institutions have historically aided or impeded the advancement of civil rights. It is necessary to intentionally design planning processes that balance the power dynamics of the process itself, with specific regard for community representation, participation, and communication.

A historic example of a lack of deep community engagement involves a land acquisition and airport expansion project at Fort Lauderdale/Hollywood International Airport (FLL). With the goal of converting a noise-impacted area to an industrial park, FLL airport officials conducted a large housing buyout initiative in 1987 that left many vacant homes standing in 1990. Remaining residents reported that the airport allowed the purchased homes to fall into disrepair. Residents argued that the degradation of vacant homes made the community look like “a warzone” (Samples 1988). The Ravenswood Civic Association President noted that the county repeatedly cited homeowners while failing to cite the aviation department for code violations (Neal 1989). Years after the buyout program was complete, one person noted that she was compensated and happy with her new residence a few miles further west of the airport, but remained critical of the process, particularly the “inconsistent methods of compensation” for property owners (Kaye 1994). This example shows that the actions of the airport did not inspire a sense of fairness, trustworthiness, or neutrality from community members.

In another example, deep community engagement and sustained partnership resulted from a federal initiative, EPA’s Near-port Community Capacity Building Project – Technical Assistance Pilots. In 2016 and 2017, the EPA provided grants for four Community-Port Collaboration Pilot Projects (U.S. EPA 2022a). One of the pilot projects was a partnership between the Port of Seattle, which operates Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, and a local health equity nonprofit organization, Just Health Action. Participants received direct technical assistance from EPA to build capacity and to improve collaboration between the port and two near-port communities that experience environmental justice issues related to port operations. After the pilot phase of the project was completed, in 2019 the Port of Seattle Commission formalized their commitment to community engagement and capacity building by adopting Resolution 3767, the Duwamish Valley Community Benefits Commitment, and passing a motion to build the Duwamish Valley Community Equity Program. The resolution was the first of its kind in which a port committed to community partnership to address environmental justice issues (Port of Seattle n.d.).

The Port of Seattle and Duwamish Valley Community partnership reached its three-year anniversary in 2022. A community advisory group, called the Port Community Action Team, guides work under the partnership; it is made up of representatives from both South Park and Georgetown. The program opened an economic development center in the South Park community to promote workforce development initiatives. It led the transformation of a prior industrial site into a park with shoreline habitat and public access to the Duwamish River. It spearheaded a project to rename six parks along the Duwamish River to reflect the cultural and historical significance of the sites based on input from

thousands of community members (Billingsley 2022). These are just a few examples of how the program is working toward its goals of community-port capacity building, healthy environment and communities, and economic prosperity in place (Port of Seattle n.d.).

Following the pilot projects and additional stakeholder outreach, the EPA finalized and published the collaboratively developed Near-port Community Capacity Building Toolkit used throughout the pilot activities. The Toolkit consists of the Community-Port Collaboration Toolkit, the Ports Primer for Communities, the Community Action Roadmap, and the Environmental Justice Primer for Ports. These along with the additional Community-Port Collaboration resources and training materials are available online from the EPA and could prove useful for airports, along with ports, when improving environmental performance and quality-of-life conditions through building equitable, deep community engagement programs (U.S. EPA 2022a).

5.3.5 Limitations and Challenges in Current Airport NEPA Environmental Justice Practice

Regulatory definitions of environmental justice, and the processes and metrics that governments use to measure environmental justice are often at odds with definitions from equity-focused planning experts. EPA defines environmental justice as:

“the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. This goal will be achieved when everyone enjoys: the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards, and equal access to the decision-making process to have a healthy environment in which to live, learn, and work...Fair treatment means no group of people should bear a disproportionate share of the negative environmental consequences resulting from industrial, governmental, and commercial operations or policies. Meaningful involvement means: people have an opportunity to participate in decisions about activities that may affect their environment and/or health; the public’s contribution can influence the regulatory agency’s decision; community concerns will be considered in the decision-making process; and decision-makers will seek out and facilitate the involvement of those potentially affected” (U.S. EPA 2022).

In contrast, one scholar argues “that the pursuit of stable, consensual definitions of such terms as environmental justice…is misguided. We must accept that people in different geographic, historical, political, and institutional contexts understand the terms differently...we need to treat the breadth and multiplicity of interpretations as guides to more relevant and useful new research” (Holifield 2001).

Additionally, the National Black Environmental Justice Platform asserts 17 principles of environmental justice which were originally drafted and adopted by delegates at the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership (POCEL) Summit in 1991. The Summit took place in Washington, D.C., and was attended by over 650 delegates representing every state, plus Mexico, Chile, and other countries (NBEJN 1991). The POCEL was significant because it was one of the first times racialized people organized themselves under a global agenda, committed to self-determination, and committed to

pursue climate justice work that centered people most likely to be negatively impacted by climate change. EPA acknowledges that it’s “definition was developed 25 years ago to capture the Federal Government’s knowledge of the issue at that time and to provide an actionable definition for regulation. The environmental justice field has developed its own definitions based on people’s work and life circumstances. These definitions…capture a vision that goes beyond regulatory requirements” (U.S. EPA 2020).

Regulatory definitions, associated with environmental analysis completed under NEPA rely on quantitative metrics and significance thresholds to construct narratives about whether exposure to environmental harms is appropriate. The goal of environmental justice analysis during the NEPA process is to detect, avoid, minimize, and mitigate planning decisions that exacerbate spatial manifestations of disadvantage (harm) for systemically divested groups. Therefore, environmental justice analysis in airport planning has focused on measuring the distribution of benefits and harms that result from a specific action, project, or policy. In the airport environment, significant actions can include siting new airports, expanding existing airports, redevelopment, reorienting airfields, and altering operational flight procedures. Though airports are expected to consider many resource categories to determine whether there are environmental impacts (as defined by NEPA), the spotlight is most frequently on noise, air quality, water resources, local employment, and regional economic impacts.

There are methodological concerns regarding the practice of environmental justice analysis across the transportation sector, including airport facility planning. Most frequently, these concerns are related to the nature of the environmental impacts that are investigated (e.g., challenges in incorporating climate change), the informational value of quantitative metrics (e.g., existing noise metrics might not necessarily articulate actual human health impacts), the methods for selecting comparison geographies (e.g. hyper-local comparison geographies mask regional social inequities when high concentrations of marginalized groups are located near the airport), and the methods for defining and mapping various marginalized population groups (e.g., communities may not be defined in a manner consistent with their cultural identities, and they may be under-sampled by formal census data collection processes).

A study of environmental justice analysis in airport planning practice evaluated environmental justice analyses and narratives in 19 environmental impact statements for U.S. airport expansion projects from 2000 to 2010 (McNair 2020). It found that these environmental justice analyses did not result in consistent detection of environmental justice impacts, nor did they consistently confer importance to those impacts when high proportions of protected populations were detected. If environmental justice is not reported in the NEPA analysis as a significant impact, the consequence is that there is no expectation for the facility owner to work towards reconciliation with impacted populations. The study makes three recommendations that correspond to research gaps regarding equity and environmental justice analysis in the airport planning process:

- Improving methodologies that define the comparison geography. More work is needed to understand how those metrics can be diversified to better contextualize both the local and regional demographics of the airport’s impact area.

- Developing methodological practices that are context-sensitive and collaborative with the local community. For example, expanding the scope of public meetings to include discussions and activities that allow communities to provide feedback on how they are measured and summarized during impact analysis. This could lead to more equitable interpretations of different metrics and impact thresholds.

- Strengthening “good neighbor” practices through partnerships with organizations that provide resource programs that meaningfully improve health and quality of life for communities experiencing adverse impacts.

5.3.6 Infrastructure Access and Belonging

Policing or limiting access to public space in and near airports is a present-day legacy of systemic oppression related to both mobility and place. For example, limits to facility access during overnight hours, anti-sit-lie measures, defensive design, and hostile architecture are intentional policy or design choices that make public spaces (including airports, pre-security) uncomfortable or unpleasant to occupy for a long period of time. These policies and design choices intend to deter crime, inhibit unauthorized uses such as skateboarding, and prevent unhoused individuals from accessing, utilizing, or sleeping in spaces (Kohlstedt and Mars 2020). Intentionally designing public spaces to exclude, restrict, and alienate certain populations is unjust.

ACRP funded research report, Strategies to Address Homelessness at Airports, was published in 2023 (Fordham et al. 2023). The research scope notes that “Many airports wrestle with how to balance their primary function of serving the traveling public with dealing respectfully with people experiencing homelessness…” The eight strategies described in the report intend to “help airports partner with local community-based resources for developing and implementing strategies to address homelessness at airport facilities.” (The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2021)

On the secure airside, airport access remains restricted due to TSA security requirements put in place following 9/11. TSA requirements limit secure airside access to travelers who must provide photo identification and a boarding pass to pass through security. Security measures limit post-security access, excluding people who are not ticketed. Thus, the ability to afford an airline ticket is an obstacle to accessing airport amenities, businesses, concessions, experiences, and public spaces that local community members may be interested in accessing.

In 2017, Pittsburgh International Airport became the first airport to work with TSA to allow a day pass option for non-ticketed passengers to access post-security facilities. Since then, a small number of airports in the United States have created visitor pass programs for people and families who want to access the airport without an airline ticket. These programs allow visitors to visit airport concessions and stores, walk their loved ones to their boarding gates, and watch aircraft arrive and depart. Such opportunities make the airport more accessible to the community and generate a broader sense of belonging at the airport. The programs require participants to go through TSA security screening procedures and typically have a reservation system or daily pass limit so that they do not lead to crowding or inefficiencies at the airport (Baskas 2021). Some airports also offer virtual or in-person familiarization tours for people to learn about the travel experience and airport facilities (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2021b).

5.3.7 Racial Profiling of Passengers

The U.S. DEA patrols airport facilities, in addition to other transportation facilities, using a variety of tactics. DEA agents use “cold consent” encounters as a tactic to approach travelers whom they have either randomly selected or whom they have determined is exhibiting behaviors consistent with drug trafficking, with the goal of obtaining their consent to speak with and search the traveler. The cold consent tactic is known to be “more often associated with racial profiling than contacts based on previously acquired information” [Office of the Inspector General (OIG) 2015, i].

In a 2015 report initiated after complaints from airport travelers, the U.S. Department of Justice recounted the experience of one Black woman who was targeted for a cold consent encounter:

“A lawyer for the Department of Defense who was traveling on government business complained to the OIG that, as she was on the jetway preparing to board her flight, she was approached by DEA agents, told that she was being stopped for “secondary screening,” and was then subjected to aggressive and humiliating questioning by the agents. No funds were found or seized during the incident. When the OIG investigators sought information from the DEA regarding the incident, they were told that no documentation of the event was prepared by anyone on the DEA task force because documentation is only completed for contacts that result in “positive” results, namely where drugs are found or funds are seized.” (Office of the Inspector General 2015, 2)

In 2022, comedian Eric André filed a lawsuit against Clayton County due to his own experience with a cold consent search in the jet bridge while departing Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport in Georgia.

“Few if any airline passengers in the post-9/11 world, focused on boarding their flight and stuck in a narrow jet bridge, would feel at liberty to walk away from armed law enforcement officers who unexpectedly intercept their path, question them, and take their boarding pass and identification, the lawsuit says. Andre’s attorneys allege a pattern of racially motivated airport stops they say are neither consensual nor random. The [Clayton County Police Department] jet bridge interdictions rely on coercion, and targets are selected disproportionately based on their race, the lawsuit claims. It was traumatizing, I felt belittled and I want to use my resources and my platform to bring national attention to this incident so that it stops, Andre said.” (Abusaid 2022)

Fellow comedian, Clayton English, joined André’s lawsuit citing his own cold consent search experience at the same airport. From 2020 to 2021, the Clayton County Police Department logged the racial identity of 378 persons they stopped on airport jet bridges and 56 percent were reported as Black (Abusaid 2022). Due to civil forfeiture laws in Georgia, the police can keep 100 percent of cash seized during cold consent searches even if the owner has no connection to a crime. From August 2020 to April 2021, only 8 percent of passengers whose cash was confiscated by Clayton County police were charged with a crime (Sibilla 2022). The onus is on the individual to legally fight for return of their property, which is a cost-prohibitive endeavor for most travelers.

If a traveler is caught committing a crime, there are equity concerns related to the justice system’s disproportionate punishments and sentencing given to Black individuals. In her book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander outlines the ways in which the criminal justice system is used to “label people of color ‘criminals’” and then legally “discriminate against criminals in all the ways that it was once legal to discriminate against African Americans”

(Alexander 2012, 2). For example, Alexander describes the case of Edward Clary. In 1993, Clary was an 18-year-old, first-time offender sentenced to 10 years in federal prison after he was “stopped and searched in the St. Louis airport because he ‘looked like’ a drug courier” (Alexander 2012, 112). During the search, the police found less than two ounces of crack cocaine. At the time, crack cocaine offenses were punished one hundred times more severely than offenses involving powder cocaine, resulting in significantly more severe punishments for Black offenders (more likely to be prosecuted for crack cocaine) than White offenders (more likely to be prosecuted for powder cocaine).

5.3.8 Federal Policy Context

Airport operators that are part of the NPIAS and receive federal funding are subject to specific regulations and policies that influence airport planning practices and funding. Certain regulations, policies, and funding mechanisms have been implemented to rectify social injustices and the present-day implications of structural racism. This section is not intended to be an exhaustive list of all federal policies designed to address injustices, but rather a sampling that are relevant to transportation and the aviation industry.

Civil Rights Act of 1964

Federal agencies are responsible for ensuring nondiscrimination and equal opportunity within their programs and funding mechanisms under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Airports are subject to federal nondiscrimination regulations as recipients of federal grant funding under FAA grant assurances (FAA 2020). USDOT Title VI regulations state that “…no person in the United States shall, on the grounds of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise subjected to discrimination under any program or activity for which the recipient receives federal assistance from the Department of Transportation” (49 C.F.R. § Part 21, 1970). FAA regulations also prohibit discrimination based on sex, religion, and age.

National Environmental Policy Act

NEPA is a landmark piece of legislation passed in 1970, which requires federal agencies to evaluate and report regulated environmental, social, and economic impacts of their proposed projects or actions. NEPA also created the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) to develop policies and oversee the Federal Government’s implementation of NEPA reporting requirements. Due to the extensive reporting policies established in the NEPA legislation, a new planning process emerged for federal infrastructure which is now commonly referred to as the “NEPA process.” Further, as the Federal Government passed subsequent environmental regulations a broader, more comprehensive “National Environmental Policy” emerged (U.S. EPA 2022; 42 U.S.C § 4321-4370h, 1970). NEPA applies to airports whenever there is a federal action, such as the use of federal funds (AIP grants) for airport infrastructure projects or FAA approval of airport layout plans for example. Therefore, airports are expected to adhere to the most current established National Environmental Policies.

President Clinton established the first E.O. for environmental justice in 1994, which formalized a federal definition of environmental justice into the NEPA process. Subsequent federal guidance on how agencies should develop and implement practices to evaluate and enhance environmental justice has since been released [see E.O. 12898 and content on the Federal Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice (EJIWG) in the E.O. subsection of this section].

The CEQ periodically develops revised NEPA implementing regulations for federal agencies. It is common practice for federal agencies to develop their own orders and internal guidance to implement federal

regulations established by Legislative and Executive Branches. For example, the Secretary of the USDOT and leadership in the FAA have published a variety of documents that guide the agencies’ implementation of NEPA, including environmental justice considerations, the USDOT issued Order 5610.2(a), Final U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) Environmental Justice Order, the FAA issued Order 1050.1F, Environmental Impacts: Policies and Procedures, and the FAA Office of Airports, Order 5050.4B, NEPA Implementing Instructions for Airport Actions.

Executive Orders

There are several E.O.s that address environmental justice and equity that pertain to federal agency actions, including USDOT and the FAA, and therefore are important for airports to understand. These include:

- E.O. 12898 Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations

- E.O. 13166 Improving Access to Services for Persons with Limited English Proficiency

- E.O. 13985 Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government

- E.O. 14008 Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad

- E.O. 14091 Further Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government

- E.O. 14096 Revitalizing Our Nation’s Commitment to Environmental Justice for All

E.O. 12898 Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations and DOT Order 5610.2(b) requires federal transportation agencies to identify whether a federal action could have disproportionately high and adverse effects on minority and low-income populations. E.O. 12898 created the federal EJIWG in 1994. The EJIWG’s NEPA Committee published Promising Practices for EJ Methodologies in NEPA Reviews in 2016, providing information to federal agencies for approaching environmental justice considerations in NEPA projects. It also published a Community Guide to Environmental Justice and NEPA Methods in March 2019, intended as a resource to communities for working with federal agencies through the NEPA process on environmental justice considerations. Additionally, E.O. 13166 requires federal agencies to provide language services for persons with limited English proficiency to enable meaningful and equitable access to information.

The 2020–24 Biden Administration has committed to advancing racial equity as a priority for the Federal Government through a systematic approach and creation of agency-specific equity action plans. E.O. 13985 Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government intends to advance equity and increase generational wealth in historically underserved communities through various initiatives. By way of E.O. 13985, an Advisory Committee on Transportation Equity (ACTE) was formed under the Federal Advisory Committee Act. The ACTE will work “to provide advice and recommendations to the Secretary of Transportation on comprehensive, interdisciplinary issues related to transportation equity from a variety of stakeholders involved in transportation planning, design, research, policy, and advocacy in pursuit of the department’s equity goals.” (U.S. Department of Transportation 2023)

The Biden Administration created the Justice40 Initiative in response to E.O. 14008 Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad “to confront and address decades of underinvestment in disadvantaged communities” (USDOT n.d.-a, para. 1) At the USDOT, Justice40 “is an opportunity to address gaps in

transportation infrastructure and public services by working toward the goal that at least 40 percent of the benefits from many of our grants, programs, and initiatives flow to disadvantaged communities” (USDOT n.d.-a, para. 2). The Office of Management and Budget, CEQ, and National Climate Advisor issued Interim Guidance on calculating benefits and reporting requirements for Justice40 covered programs in 2021 (Office of Management and Budget 2021).

E.O. 14008 created a White House Environmental Justice Interagency Council within the Executive Office of the President, led by the Chair of the CEQ whose membership represents the leaders of federal agencies and cabinet members. This group was tasked with leading the Federal Government’s approach to addressing environmental injustice, creating performance metrics, and ensuring accountability. The E.O. also created the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council within the EPA to provide recommendations to the Interagency Council and represent broad perspectives on the topics of environmental justice, climate change, and racial inequity.

E.O. 14091, Further Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government, creates a requirement for federal agencies to create an Agency Equity Team and a White House Steering Committee on Equity to coordinate actions across the Federal Government.

E.O. 14096, Revitalizing Our Nation’s Commitment to Environmental Justice for All, issued in April 2023, continues to build on the Biden Administration’s other related actions including E.O. 14008, E.O. 12898, and Justice40. This E.O. reinforces direction to federal agencies to implement “meaningful public involvement” to make information about environmental and health impacts available to communities. It establishes an Environmental Justice Subcommittee of the National Science and Technology Council within the Office of Science and Technology Policy, along with a White House Office of Environmental Justice within the CEQ, implements a reporting requirement for all federal agencies on their Environmental Justice Strategic Plans to the CEQ, and includes requirements to assess and publicly report progress towards agency goals.

Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

The 2021 BIL includes a focus on environmental justice and investment in historically underserved and disadvantaged communities. The BIL provides historic funding for investments in transportation, including aviation. Through the BIL, the FAA has an opportunity to “build safer and more sustainable airports that connect individuals to jobs and communities to the world” (FAA 2021, para. 2). The law provides $15 billion for airports to invest in infrastructure projects related to runways, taxiways, safety, sustainability, terminal, airport-transit connections, and roadway improvements over 5 years (FAA 2021). It also includes $5 billion in funding for airport terminal development projects and an additional $5 billion in funding for updates to air traffic facilities. The BIL provides historic funding opportunities for infrastructure in under-resourced communities but recognizes that these communities also require tools to access and deploy that funding. Several federal technical assistance programs for transportation projects exist for state, local, and tribal governments to take advantage of the historic funding opportunities (Build.gov 2022).

Inflation Reduction Act

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act invests in clean energy and climate action through various economic tools such as grants, loans, rebates, and tax provisions. It intends to create jobs, lower energy costs for consumers, encourage investment in disadvantaged communities, reduce emissions, and accelerate private investment in clean energy solutions and infrastructure. The Inflation Reduction Act supports the Justice40 Initiative and aims to benefit communities with environmental justice concerns and legacy

pollution, including a $3 billion environmental justice grant program. It also targets benefits to working families, tribes, rural communities, and communities that were historically reliant on fossil fuel extraction, processing, or storage. The Inflation Reduction Act also incentivizes development and support of clean transportation fuels and infrastructure, including sustainable aviation fuels. It includes both a Sustainable Aviation Fuel Credit and the Alternative Fuel and $297 million in funding for the FAA Low-Emission Aviation Technology Program (the White House 2023).

U.S. Department of Transportation Equity Plans

The USDOT committed to centering equity through its most recent DOT Strategic Plan (Fiscal Year 2022–2026) which elevates equity as a strategic goal of the department and through its Equity Action Plan created in response to E.O. 13985 (January 2022). The USDOT is focused on four equity objectives centered on communities: expanding access, wealth creation, power of community, and interventions. “USDOT is using these focus areas to develop concrete actions that will thoughtfully redress historic inequities, positively impact historically underserved or overburdened communities in meaningful ways and ensure that the department is equipped to equitably deliver its resources and benefits” (USDOT 2022, 3).

USDOT equity efforts also highlight advancing access and opportunity for individuals with disabilities through the ADA of 1990 and its 2022 Disability Policy Priorities. The priorities are “enabling safe and accessible air travel; enabling multimodal accessibility of public transportation facilities, vehicles, and rights-of-way; enabling access to good-paying jobs and business opportunities for people with disabilities and enabling accessibility of electric vehicles and automated vehicles” (USDOT n.d.-b, para. 1).

Federal Aviation Administration

The FAA is responsible for ensuring safe and efficient air travel throughout the United States. The FAA provides technical guidance on airport planning and development and funds development of airport infrastructure through various grants. Airport operators that are part of the NPIAS and receive federal funding via grants from the FAA are subject to FAA regulations and policies under grant assurances. As an operating mode under the USDOT, the FAA follows USDOT regulations and guidance.

E.O. 12898 Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations and USDOT Order 5610.2(b) requires the FAA to identify whether a federal action could have disproportionately high and adverse effects on minority and low-income populations. Federal actions sponsored by the FAA are subject to environmental review under NEPA, which includes environmental justice considerations. The FAA is responsible for ensuring nondiscrimination and equal opportunity under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The FAA advances access and opportunity for individuals with disabilities through the ADA of 1990. The USDOT’s DBE program and airport concession DBE program applies to airports that receive federal financial assistance. These programs seek to rectify generational wealth and business opportunity inequalities that result from the legacies of economic systems of racial capitalism.