Structural Racism and Inequity in the U.S. Aviation Industry: Foundations and Implications (2024)

Chapter: 6 The Foundations of Transportation Equity

6. THE FOUNDATIONS OF TRANSPORTATION EQUITY

LEARNING GOALS

This chapter aims to pivot the reader toward ideas and framing techniques that center equity and justice as aspirational goals within transportation planning. The first subsection provides examples of geographic inequities that are important to recognize when planning transportation systems. The next section explains how social justice movements have laid groundwork for scoping and defining justice within the transportation discipline. The third and final subsection summarizes the prevailing approaches to justice that are common within the equity planning subfield.

This chapter allows the reader to:

- Apply geographic typologies to identify equity gaps for specific communities.

- Identify several key movements for social justice and civil rights as they relate to the imperative of equity.

- Recognize and differentiate multiple conceptions of justice.

INSIGHT WARM-UP

Historical Context

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s is a prominent part of American history. What details do you recall about the various movements for social justice related to racialization, disability, gender, and sexual identity, and/or environmental justice? How have these prior and ongoing movements shaped contemporary ideas of mobility justice?

![]()

Lenses and Ways of Knowing

The process of racialization and systems of oppression influence the broader spatial patterns of human settlement. These spatial patterns and geographies are important to recognize when planning transportation systems and infrastructure.

Racialized geographies are geographies whereby boundaries, policies, zoning practices and governance structures either create, reinforce, or resource processes of racialization. What differences have you noticed between rural areas, urban areas, and suburban areas – and how do you think those differences could be connected to racialization?

Present-Day Legacies in Aviation

Within transportation planning, simplistic and shallow interpretations of equity have systemically produced a myriad of inequities within community engagement processes and investment. Integrating equity and justice into airport planning and decision-making requires a nuanced effort that both specifically defines the past or ongoing harms and the aspirational future. What ideas, theories, and frameworks have you relied on to communicate a vision for a just future?

6. THE FOUNDATIONS OF TRANSPORTATION EQUITY

The prior chapters described the origins of inequity in the United States and demonstrated how those inequities continue to manifest in the aviation industry, specifically with respect to airports. As described in previous chapters, group-based othering, settler colonialism, the economic system of racial capitalism, and systemic oppression perpetuate harm broadly in U.S. society. To guide airport planning and decision-making toward equitable processes and outcomes, it is necessary to develop the skills to identify and name these harms as well as the historical context from which they emerged. It is also necessary to develop the skills to identify and name the aspirational goals that will guide corrective and reparative actions that interrupt these interlocking systems of harm.

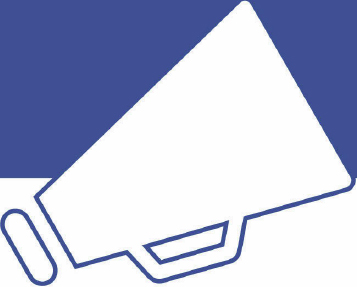

6.1 Transportation and the Geography of Inequity

Aviation facilities interact with an external built and social environment that was shaped by centuries of land use, infrastructure development, and housing policies and practices. Racialized geographies, geographies whereby boundaries, policies, zoning practices and governance structures either create, reinforce, or resource processes of racialization, directly resulted from public and private sector policies and practices that rigidly introduced and reinforced racial residential segregation (see Figure 21). These policies and practices impacted multiple racial, ethnic, and religious groups and most directly oppressed Black people (J. M. Thomas 1994). Therefore, widespread inequity is the present-day outcome of geographic racialization.

Source: The Ohio State University

The following sections summarize these five geography-related contexts:

- Rural geographies

- Urban centers

- Suburbs

- Post-industrial centers

- Unincorporated territories

Each section highlights specific examples of the ways that processes of racialization lead to widespread inequities and broader notions of oppression within the respective geographic contexts. The examples are not unique to each geographic typology, rather they convey instances where a heightened vulnerability to particular inequities occurs in correlation to the unique spatial characteristics within each geographic typology. Aviation practitioners should consider which type of geography they impact with their work. The geographic inequities indicated herein can be used to inform a unique approach to airport planning, taking into consideration the characteristics of inequity that are most relevant to the project area.

6.1.1 Rural Geographies

Nutritional Disinvestment

Rural communities experience food insecurity and malnutrition in ways that correspond to “their ability to adapt and on the specific nature, extent, and duration of the coping strategies they adopt” (Ruel et al. 2010). While rural communities are not alone in experiencing nutritional disinvestment, the spatial layout of rural areas contributes to heightened vulnerability to nutritional disinvestment. For example, for Black low-wealth residents in rural communities, “store choice, outshopping, methods of acquiring foods [from places] other than the grocery store, and food insecurity…[became barriers because of] concerns around price, quality, and transportation” (Holston et al. 2020). Airports sited in rural geographies can consider planning to reduce food inaccessibility for residents in the project area. For example, airports can consider including healthy food options within terminals (before and after TSA checkpoints) and allow local residents to use day passes to enter airports without the requirement of flying.

Figure 22 depicts a photograph of Maria Alonso, the co-founder and Executive Director of Huerta del Valle (HdV) and Tomas Aguilar-Campos, an employee with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. HdV is a community supported garden and farm in the middle of a low-income urban community, just one mile from the Ontario International Airport in California.

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Public Domain, https://www.flickr.com/photos/usdagov/45690332284/in/photostream/

Energy Pollution and Environmental Toxicity

Environmental toxicity is not exclusively apparent in rural communities; however, contemporary zoning practices increasingly relegate toxic industry and energy practices to rural areas, resulting in uniquely intense exposure to this dynamic in rural areas. For example, historically and presently, oil and gas pipelines are sited through indigenous and rural communities (Strube, Thiede, and Auch 2021). Many indigenous people in the United States now live in areas that are technically urban areas (Weaver 2012); however, indigenous histories, cultural landscapes, sacred artifacts, and burial grounds are directly negatively impacted by the siting of oil and gas pipelines in rural regions (Emanuel et al. 2021). As rural areas are replanned to support industrial uses, state and federal Departments of Transportation decision-making can be definitively linked with environmental inequities in rural areas (Caretta and McHenry 2020). Airport planning exercises should include preventing or mitigating existing installation of toxic infrastructure.

Aging in Place

Aging in place is a decision people make based on factors such as affordability, proximity to relatives, access to essential services, and preferred leisure activities. When people either choose or are relegated to aging in place in rural areas, transportation inaccessibility can contribute to negative outcomes for aging adults. As social cohesion is a primary determinant of quality of life for aging adults, transportation

accessibility consequently directly informs whether aging adults in rural communities can access places, processes, and activities that promote social cohesion (Henning-Smith et al. 2022). Results from an AARP poll show that “about three-quarters of those 50+ would like to stay in their current homes or communities for as long as possible” and that they prefer to live independently as they age and near family (Marek et al. 2005; Binette 2021). People are increasingly looking to rural areas to live near infrastructure and programs that are specifically designed for aging adults (Skoufalos et al. 2017). Airport practitioners focusing on community engagement can create programs that strengthen confidence and comfort for aging adults traveling through airports.

6.1.2 Urban Centers

Poverty and Ghettoization

For several decades, the term blight has been used to describe the eroding conditions of low-wealth neighborhoods within urban centers (Herscher 2020). The advent of what is now known as the Interstate Highway System and the concurrent spread of ideological suburbanism in the 1940s is documented as the beginning of a mass migration of racialized people to urban centers and white flight to surrounding areas now known as suburbs (Imperatore 2007). As white flight was reinforced by redlining, the cycle of segregation was compounded by municipal disinvestment and resulted in widespread poverty that continues to manifest as barriers to accessing food (Walker et al. 2021), transportation (Gibson 2007), healthcare (Bennett 1999), and dignified housing in inner cities.

Over time, urban centers became criticized and urban center inhabitants became criminalized for the socioeconomic challenges being faced by people who live there. Key municipal and federal decision-makers began implementing policies which Anna Maria Santiago called a “war on the poor” such that, “the weapons of choice [in the war on the poor] include decreasing and threatening to eliminate welfare benefits to poor mothers unable to work or find jobs; increasing the punitive conditions under which assistance is provided; and stirring up contempt of the poor among those who are more fortunate” (Santiago 2015). John R. Logan and Deirdre Oakley (2017) later interrogated the war on the poor and developed a theoretical framework that derives from racialization as a concept—the process of ghettoization. Ghettoization has been described by scholars in the following way: “Ghetto [is an idea used to] (1) highlight the difference between Black neighborhoods and other neighborhoods; (2) ascribe ghetto conditions to a vicious cycle of outside repression and inside decay; and (3) argue that the separate institutions brought about by the ghetto were inherently inferior to those outside while still serving as a source of pride and a rounded life” (Drake and Cayton 1993). New airports and airport expansions should avoid exacerbating ghettoization by ensuring local residents have access to work associated with the airport and by investing in community infrastructure in the immediate vicinity of the airport.

Policing Mobility

Policing is a function of ghettoization (Logan and Oakley 2017). Written histories regarding the origins of policing denote “political borders and cultural landscapes were an important source of spatial differentiation” (Hartshorne 1950; Scott 2011). Early notions of policing sought to reinforce spatial boundaries which symbolically, literally, and socially create and rely on classism, racism, misogyny, and homophobia. Present-day iterations of policing in urban centers disproportionately result in death, increased poverty, and health disparities for racialized and low-wealth people in the following ways: hyper-surveillance; citizen vigilantism (Onwuachi-Willig 2016); the imposition of fees and fines (Pacewicz and Robinson 2021); codified restrictions on movement such as anti-cruising ordinances (Gofman 2002),

anti-loitering restrictions (D. E. Roberts 2016), and presumptive gang injunctions (Bloch and Meyer 2019). Airports can consider staffing interventionists who are not law enforcement to provide travelers with an alternative means of accountability and structure in the airport setting.

Housing Instability

The historical process of ghettoization has especially impacted housing stability in urban centers. Areas with dense poverty have historically been referred to as slums: “areas in which the housing is so unfit as to constitute a menace to the health and morals of the community, and that the slum is essentially of social significance” (Dickerson 2015).

Recent studies add a layer of analysis to the issue of housing instability and its relationship to transportation planning by clarifying, “[A Department of Transportation] does not create bicycle infrastructure in order to raise property values. Building owners and developers, however, have learned that the city’s streetscape improvements can create more attractive spaces, and the presence of bicycle infrastructure near a development can be a selling point for affluent young newcomers” (Stein 2011). While low-wealth and racialized people use, rely on, and advocate for transportation infrastructure and innovation, the introduction of transportation infrastructure and facilities into neighborhoods suffering from disinvestment is measurably known to invoke housing speculation and increase costs of living. Furthermore, advocates within these communities have been vocal about the erasure and neglect of lived experiences and the unique needs of racialized and low-wealth people during community engagement processes associated with the implementation of transportation-related investments (Hoffmann 2016). Airports can work with local housing justice groups to ensure the siting or expansion of airports will not invoke housing speculation. Community engagement campaigns celebrating existing residents and workforce access programs can help achieve this aim.

6.1.3 Suburbs

Suburban Culture

There are varying definitions of the classification of suburbs as a geographic typology (Kurtz and Eicher 1958). Often, American suburbs are characterized as low-density developments with single-family residential zoning (colloquially referred to as ‘bedroom communities’) and sprawling residential amenities. The spatial distance between suburban areas and urban centers, and, consequently, the transportation systems built to and through suburban areas, are additional distinguishing characteristics of the suburb (Johnston 1973).

Similar to rural areas, suburbs were socially constructed as ideal departures from living in proximity to racialized and low-wealth people in dense, urban centers (Logan and Collver 1983). The reality of a suburban community was made possible for White people by way of the GI Bill, redlining, and the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. Fueled by the premise of racial superiority, white flight to the suburbs manifested a set of ideologies that reinforced racism through land use practices and residential patterns (Kruse 2007). This form of xenophobia has informed the unique challenges racialized people and low-wealth people experience in suburban neighborhoods (Browner 2013). The gamut of socio-political inequities associated with suburbanism stems from homophobia and transphobia (Swank, Frost, and Fahs 2012), reproductive repression, religious polarization (Warf and Winsberg 2010), and deadly gun culture (Yamane 2017). By incorporating airport policies that disrupt hetero-normativity, airports sited in suburban communities will aid in shifting paradigms that have been particularly harmful toward underrepresented people.

6.1.4 Post-Industrial Centers

Industrial Paternalism

Post-industrialism is described by social scientists as being a point in history when cities that were once industrial centers were transformed by a nationwide trend which outsourced manufacturing and prioritized service-based industries. While this nationwide change is documented as having begun in the 1970s (Brueggemann 2000), many cities (which can also be characterized as urban centers) continued to carry the burden of industrial demand for the entire United States (Newman 2009).

To sustain industrialism as an economic model while many other cities moved into a post-industrial economy, employers incentivized and subsidized industrial workers living near job sites, sometimes in employer-owned residences (Kasarda 1989). This created a dynamic of paternalism whereby employees were subject to surveillance and faced losing their jobs, and subsequently their housing, if they were not compliant (Bates 2003). Public transit investments that ensured employee access to work represent a lingering outcome of industrial paternalism. With the phasing out of industrial jobs, cities began to offer welfare programs to prevent a sudden migration away from struggling industrial centers (Wingerd 1996). The literature regarding the history of post-industrial centers refers to this cycle of dependence as welfare capitalism (Hicks 2018).

Because of white flight to rural and suburban areas, many post-industrial cities became Black-majority cities (Clerge 2019). These cities continue to experience ghettoization and disinvestment as a result of racialization and the stigma associated with the low-wealth inhabitants of post-industrial centers (Draus, Roddy, and Greenwald 2010). Additionally, residents in post-industrial centers continue to suffer from high levels of environmental toxicity. When coupled with disinvestment practices (e.g., perpetually under-maintained roadway infrastructure, water and sewage facilities, transit stations, and open spaces), this exacerbates negative health outcomes for inhabitants of post-industrial centers. Community-led planning exercises will serve as an investment in self-determination through aviation planning exercises.

6.1.5 Unincorporated Territories

The United States currently has 13 “unincorporated territories” that are classified as “organized” as they have governments with restrictions to their autonomy. American Samoa is an unorganized unincorporated territory without autonomy because the United States Government has not recognized it as having a “permanent population” (Wood et al. 2019). The 14 unincorporated territories (including both organized and unorganized) are Puerto Rico, Guam, United States Virgin Islands, Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, Midway Atoll, Palmyra Atoll, Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Wake Island, and Navassa Island (N. M. Torres 2013). The histories of Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands provide examples of the process of racialization that impacts residents living in unincorporated territories.

Puerto Rico

Some scholars use the term colony in reference to Puerto Rico, “a polity with a definable territory that lacks legal/political sovereignty because that authority is being exercised by a peoples that are distinguishable from the inhabitants of the colony” (Argüello 2015). On July 25, 1898, the United States invaded Puerto Rico and gave Spain $20 million to end the sovereignty of Cuba and to cede Guam (Pacific Islands) and Puerto Rico entirely. Puerto Rico is mostly inhabited by racialized people and there is a contentious relationship to Blackness that persists as a result of Puerto Rico’s legacy of racism. Prior

to the United States invasion of Puerto Rico, the Spanish National Assembly abolished slavery in 1873, granted former slavers “35 million pesetas per enslaved person,” and required enslaved people to continue working for 3 years as a form of reparations (I. P. Godreau 2015).

Initially, as a territory, Puerto Rico was not afforded a Bill of Rights and people from Puerto Rico were not afforded United States citizenship or access to travel between Puerto Rico and the mainland of the United States (Duany 2017). A year after the invasion of Puerto Rico by the United States, the United States Supreme Court ruled in the Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sandford decision that “[territories] are acquired to become [states]; and not to be held as a colony and governed by Congress with absolute authority” (Taney 2009), but the justices did not rule on the matter of Puerto Rico’s incorporation, and vaguely suggested United States Congress’ powers regarding Puerto Rico were unlimited except for constitutional principles that “are the basis of all free government[s]” (Taney 2009). Consequently, people in Puerto Rico could travel to and from the mainland of the United States and Puerto Rico’s constitution was ratified by the United States Congress in 1952, granting Puerto Rico commonwealth status and “state-like” benefits, despite Puerto Rico remaining unincorporated. The unincorporated status of Puerto Rico invoked a socio-cultural dynamic referred to as “race mixing”–a process by which some people of Puerto Rico sought to establish proximity to whiteness, and consequently the United States, over time (I. Godreau 2002).

United States Virgin Islands

The Virgin Islands of the United States consists of Saint Croix, Saint John, Saint Thomas and 50 surrounding smaller islands and cays (Scheyvens and Momsen 2008). These islands are separate from the territories known as the Virgin Islands and Caribbean Islands which include the British Virgin Islands.

St. Thomas was initially sought after by Europeans seeking to colonize its indigenous residents for the purposes of harvesting and extracting sugar cane, cotton, indigo, and agriculture. By 1671, Denmark had taken over the trade of agriculture in St. Thomas, facilitated by the enslavement of Africans whom they began kidnapping and transporting to St. Thomas as early as 1673; mass kidnapping and enslavement began in 1673 (Handler 1998). A successful uprising of enslaved Africans kept Denmark from expanding slavery to St. John in 1684. St. Croix remained a hub of chattel slavery through the Trans-Atlantic slave trade under the colonization of France; Denmark occupied the island by way of a purchase agreement between Denmark and France in 1651. While slave trade was abolished in 1803 when the region was made a free port by Denmark, the British reoccupied the territory and reverted to Danish rule, re-codifying slavery. Slavery was not decodified in the region until 1848 as a result of successful uprisings (N. A. T. Hall 1992).

As the production and trade of sugar cane was drastically reduced following the abolition of slavery, the United States declined to purchase what is now known as the United States Virgin Islands in 1870. However, during World War I, the United States purchased the Virgin Islands as a show of force to restrict access to the Panama Canal. While the United States agreed to recognize people in the United States Virgin Islands as citizens, people who wanted to identify as Danish were excluded from United States citizenship. In 1932, United States citizenship was expanded to all natives of the Virgin Islands who lived in the continental United States or any of its territories. The United States and Great Britain have collectively gone on to extract resources from the Virgin Islands through the tourism industry, disincentivizing struggles for statehood in either British or United States territory (N. A. T. Hall 1992).

Hurricane Impacts

Both Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands are stifled by the economic constraints associated with being unincorporated territories (Prevatt et al. 2018). Hurricanes that have devastated the region reveal economic inequities which underscore the ways those living in unincorporated territories suffer as a result of processes of racialization. For example, Puerto Rico experienced major infrastructure challenges following Hurricane Maria in 2017. Rosa E. Ficek (2018) “argues that the experience of obtaining food, water, power, and other necessities in the aftermath of Marıa revealed, in an embodied way, the racialization of Puerto Ricans as colonial subjects,” and that “the construction of racial inferiority felt a certain way when modern infrastructure was intact and felt a different way when that infrastructure was destroyed by the storm.”

In the months following Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico officials reported that “18 bridges, six primary roads, six secondary roads, and more than 14 tertiary roads were closed to main transit” (Colucci 2018). While this scale of inaccessibility is significant, residents reported additional disrepair and inaccessibility. In a study that collected the views and perspectives of Puerto Rico residents a year after Hurricane Maria, residents described ongoing struggles such as not having access to grid power for more than 4 months, compounding unemployment, displacement, loss of access to a personal vehicle, no access to clean water, worsened health conditions, and an inability to access and store food (DiJulio, Muñana, and Brodie 2018). Residents also expressed having the impression that if Puerto Rico were considered a state, they would have been more supported by the United States Government. The legacy of culturally-ingrained anti-Blackness and neglect by way of non-incorporation results in disproportionate inequities for people in Puerto Rico, which are exacerbated and increasing as hurricanes and other extreme weather affect the region (Figueroa 2020).

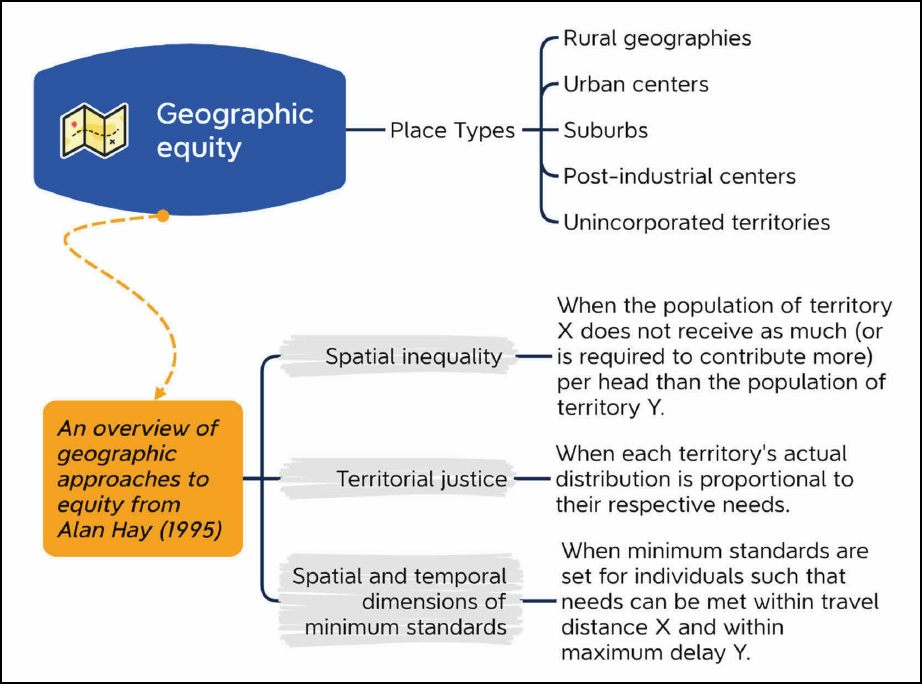

6.2 Movement Building and its Influence on Transportation

The contention of land ownership and its resulting processes of racialization as expressed through geographic inequities has not gone without resistance from impacted people and communities. Modern frameworks for equity, equality, and institutional changes have been either inspired or accomplished by way of the advancements of various social justice and civil rights movements. Slave Revolts (Genovese 2006), the Global Justice Movement, Liberation Theology Movements, Feminist and Womanist Movements (Phan 2000), Civil Rights Movements, Disability Justice Movements, the Environmental Justice Movement, and LGBTQI+ Movements (Roberts-Gregory 2022) all inform a practice-based notion of a struggle for social justice.

6.2.1 Civil Rights and Disability Justice

Many scholars credit the Civil Rights Movement as necessary momentum for the Disability Rights Movement (McGuire 1994). As the Civil Rights Movement and abolitionist groups mobilized communities to demand equity, communities began to imagine and struggle for a version of civil rights that addressed the holistic needs of people–beyond their racial identities (Anti-Defamation League 2022). In response to calls for disability justice, in 1948, as part of the National Mental Health Act, President Harry Truman established the National Institute of Mental Health. This was initiated through calls for support for those returning from WWII with cognitive disabilities. In 1960, President John F. Kennedy expanded these services through the establishment of the Panel on Mental Retardation among other committees and convenings (Berkowitz 1980). Additional pressures placed on elected officials resulted in the 1975 Education of All Handicapped Children Act, which guaranteed children with disabilities the right to a public school education.

While people with disabilities continued to face interpersonal and spatial hostility in the built environment (Sherman and Sherman 2012), several protections for people with disabilities were secured through the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, one of the first overt protections against disability discrimination. Protections were codified in:

- Section 501 - Protects people with disabilities in federal workplaces and in organizations receiving federal tax dollars.

- Section 503 - Mandates affirmative action, including employment and education for minorities.

- Section 504 - Prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in the workplace and in their programs and activities.

- Section 508 - Guarantees equal or comparable access to technological information and data for people with disabilities.

When it comes to mobility planning and transportation equity, there is a persistent oversaturation of land use and transportation design considerations that lead to ableist outcomes and normative ideas of movement and mobility (Costanza-Chock 2020). While the ADA of 1990 attempted to rectify some of these challenges, mobility justice and disability advocates call for adequate considerations of (1) those whose accommodations would have considerable economic implications, (2) those whose accommodations are incongruent with other disability accommodations, and (3) those with disabilities that are not acknowledged in disability discourses (Eaton 1990).

Figure 23 depicts a photograph that was published in 1989, titled Jesse Jackson shaking hands with disability advocate Justin Dart Jr., who is in a wheelchair, during a hearing of the House Committee on Education and Labor on a bill which became the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Source: Published by R. Michaels Jenkins in 1989; Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.65015/

More recently, the implications of ableist ideology and the shortcomings of the ADA include death and severe injury resulting from policing of people traveling with cognitive disabilities (D. Thomas 2016; Boyd et al. 2020), increased sexual assault of people traveling with physical disabilities (Bowers Andrews and Veronen 1993), social alienation by way of inaccessible transit facilities, and separate and unequal paratransit systems and operating procedures (Langdon, 2016). According to the literature, the erasure, neglect, and abuse of people with disabilities is a function of a broader system of othering, oppression, and xenophobia (Imrie 1996). The social dynamics of othering people with disabilities is replicated in the ways gender nonconforming and queer-identifying people experience and access the built environment.

6.2.2 Anti-LGBTQIA+ Planning Priorities

In the United States, there is nominal availability of scholarship devoted to studying and bringing awareness to the mobility-related experiences of LGBTQIA+ people. Robert Salem notes the distinction between the pace of change of social attitudes toward LGBTQIA+ persons and the pace of change of legal and civic protections for LGBTQIA+ persons arguing that, “LGBT Americans lack legal protection, but are [incorrectly] perceived as gaining [full] acceptance and equality at a rapid pace,” which may contribute to the lack of scholarly inquiry and public concern for the hardships visited upon queer people in the United States (Salem 2017, 46). As the United States Congress has been ineffective in

enacting civil rights protections specifically for LGBTQIA+ people, the failure to codify the humanity of queer people reinforces the notion that queer is synonymous with being other.

To understand the transportation-related experiences of LGBTQIA+ people, it is useful to understand the broader experiences of othering, which show up in or are impacted by the built environment. Several overlapping inequities are related to LGBTQIA+ mobility, such as barriers to accessing sexual and reproductive care (Hubach et al. 2022); employment discrimination that results in longer commute times to jobs for LGBTQIA+ people (Lin and Cukor 2020); increased exposure to human trafficking while traveling (Langer, Paul, and Belkind 2020); and increased risk of being physically harmed and harassed while traveling (DiMichele 2020). In Minneapolis, Minnesota, queer-identifying people are twice as likely to be unhoused compared to the population of all unhoused people in the area (Pendleton et al. 2020). People who are experiencing houselessness are more likely to need and use public transportation (Ding, Loukaitou-Sideris, and Wasserman 2022).

Transgender people and gender nonconforming people face increased risk, danger, and threats in the built environment. For example, a study based in Oregon found that transgender and gender nonconforming people, while traveling, encounter harassment at much higher rates than those with binary gender identities (Lubitow et al. 2017). The study’s researchers analyzed this dynamic and found “transgender and gender nonconforming individuals experience a form of mobility that is altered, shaped, and informed by a broader cultural system that normalizes violence and harassment towards gender minorities” (Lubitow et al. 2017). What can be ascertained from studies such as the one conducted in Oregon is “an urban environment based on aggression and intolerance immobilises and renders invisible transgender” (Verlinghieri and Schwanen 2020). Specifically, transportation infrastructure (and the built environment more broadly) is designed and implemented through processes and frameworks that rely on and reproduce binary notions—like public versus private spaces. Transportation planning is typically a design exercise that places emphasis on productivity and consumption and the challenges that stem from the sector’s obsession with productivity are disproportionately amplified for gender-fluid or nonconforming people. When practitioners plan with a primary interest in moving people faster (to work, to school, or to commerce), practitioners reinforce the belief that the functions and features of transportation infrastructure should hinge on what is ideal for the normative, productive, lucrative body (Cresswell 2016). To this end, people whose gender expressions do not fit squarely within the normative gender binary construct will be more likely to experience inaccessibility, alienation, harassment, policing, and dehumanization in the built environment. While there are very few focused studies regarding the unique travel experiences of transgender and gender-fluid people, the tactics of othering, racism, and ableism speak to broader experiences and lend context to inquiries about gender-related mobility inequities (Flores et al. 2020).

6.2.3 Environmental Justice Movements

Prior to the Environmental Justice Movement that began in the 1980s, racial equity scholars critiqued environmentalism and the movement to preserve outdoor spaces because it ignored the needs of racialized and low-wealth people, primarily focusing on beautifying outdoor spaces (Bullard, Johnson, and Torres 2004). However, the Civil Rights Movement laid the foundation for the evolution of the Environmental Justice Movement. In the 1960s, civil rights leaders drew attention to the public health impacts experienced by racialized people living in proximity to toxic waste and disposal sites (Bullard 1993); this advocacy occurred prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Title VI which led to greater mobilizing around the issue of environmental justice and tasked the EPA with preventing environmental injustice and civil rights violations. Inspired by the successful tactics used in the Civil

Rights Movement, many of the same leaders entered the early Environmental Justice Movement and adopted Civil Rights Movement strategies such as mass political education, petitions, rallies, marches, coalition building among movements, nonviolent direct action, and litigation (Bullard and Johnson 2000).

Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement identified a pattern in which toxic and polluting facilities were regularly sited in low-wealth, racialized communities (D. Taylor 1992). Many mobilized to join scholar Dr. Robert D. Bullard, also known as the “Father of Environmental Justice,” who coined the term “environmental racism” in 1982 in reference to the illegal dumping and intentional disposal of environmental contaminants in Warren County, North Carolina. In the early 1980s, Warren County was home to the largest percentage of Black residents in the state. Mass protests, with over 500 activists opposing the practice of dumping contaminated soil, sought to demonstrate how environmental justice was about more than just beautification of the environment but also protecting human health and welfare. Bullard and McGurty refer to Warren County as one of the first examples of NIMBY-ism (“Not In My Back Yard”) (McGurty 1997). Other scholars highlight Warren County as a case study for how low-wealth, racialized communities were historically targeted by state and federal authorities through planning and land use decisions (Ducre 2018).

Although the protest to stop contaminated soil burial in Warren County was not successful, through research and sustained protest, Bullard and others have demonstrated that Black and Brown communities bear the brunt of environmental injustice, degradation, and pollution. In 1983, a federal report confirmed that communities in the southern United States housed a disproportionately high amount of waste sites (GAO 1983). A 1987 study conducted by the United Church of Christ’s (UCC) Commission for Racial Justice titled, Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States found, from a statistical standpoint, found that the best predictor of whether someone lives near a hazardous waste site, even after controlling data for geography and income, was the person’s race (Lee 2019; UCC 2022). Those who are both racialized and low-wealth have an even greater risk and likelihood of dangerous environmental exposure (Downey and Hawkins 2008).

In the late 1970s, prior to the Warren County protests and widespread mobilization, Bullard and his research team identified another example of Black people experiencing disproportionate environmental impacts. They found that in Houston, Texas where only 25 percent of the city’s population was Black, 14 of the city’s 17 industrial waste sites were situated in Black neighborhoods, representing over 80 percent of the city’s waste (Borunda 2021). The residents and researchers then, and now, questioned why toxin producing facilities and land use decisions were planned for predominantly Black communities and not for their white, affluent neighbors (Bullard and Wright 1987; Lee 2019). This example, among many others documented by researchers through the decades, illustrates systemic harm resulting in environmentally racist outcomes by way of land use practices and decision-making.

The tactics and justifications that are displayed through environmental racism are extensions of the legacies of redlining policies, restrictive covenants, ghettoization of Black and low-wealth communities, white flight, and increased policing and criminalization of racialized people (J. D. Roberts et al. 2022). The environmental harm worsens over time, as seen in formerly redlined communities, where the heat island effect causes the temperature to be over 10 degrees Fahrenheit higher than other neighborhoods in the same city as a result of less tree canopy cover, less open green space, and less access to central air conditioning (Hoffman, Shandas, and Pendleton 2020).

Climate change is further complicating and expanding this harm since racialized communities are often less resilient to the disastrous effects of climate change-induced conditions like frequent wildfires and

hurricanes (Borunda 2021). The racialization of geographies and an individual’s zip code are consistent predictors of an individual’s health and well-being, their exposure to increased environmental health threats, and increased likelihood of having preventable diseases (Ranniger 2020). One scholar described this threat of environmental harm as being a form of “slow violence” (Nixon 2011). This term is used because environmental threats lead to an erosion of the conditions needed to sustain human life in racialized and low-wealth communities that are neglected by local governments in favor of upholding existing systems of capitalism. The following environmental injustices (which will disproportionately burden racialized and low-wealth people) are predicted to grow in frequency and severity as climate change worsens: air pollution and particulate matter emissions exposure, chemical facility incidents and exposure to hazards, lead exposure and poisoning (particularly among children), water supply contamination, and extreme weather conditions that often lead to displacement (Ranniger 2020).

In response to deteriorating environmental conditions and increased injustices, racialized communities are rebuilding movements and organizing coalitions to address environmental injustices. One example is the successful protest in Central Valley, California against an incinerator site, proposed by the California Waste Management Board after a 1984 commissioned report suggested that low-income, rural, Catholic communities might demonstrate the least resistance to toxic waste incinerators in their communities (J. S. Powell 1984). The Central Valley was the site of another early example of environment-related protests that connected issues of labor, capital, and impacts of environmental harm. In the 1960s Cesar Chavez and Latinx agricultural workers successfully led a struggle for labor rights and protection from exposure to harmful pesticides (Shaw 2011). As another example, The Dakota Access Pipeline protests of 2016 and the Enbridge Line 3 protests of 2021 in Minnesota popularized and brought attention to the construction of pipelines through indigenous lands and communities (Hunt and Gruszczynski 2021). Pipelines displace people and destroy natural habitats and resources. To protest pipelines and resist the expansion of energy injustice, activists have united across coalitions ranging from climate and environmental justice advocates, racial justice advocates, land back and Indigenous sovereignty movements, decommodification of land use advocates, police violence activists, and anti-military activists (K. P. Whyte 2017).

As of 2018, over 150 organizations have established a coalition to achieve a Just Transition from current systems of harm and oppression to a new set of systems rooted in equity to repair the effects of the experience of racialization, to end environmental injustice, to restore Indigenous sovereignty, and to provide reparations for the descendants of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade (Climate Justice Alliance 2018). The framework is conceptualized in the Red Black and Green New Deal (RBG New Deal) (Donaghy and Jiang 2021). The RBG New Deal asserts that Black and Indigenous communities bear the brunt of climate crisis impacts that are further exacerbated by systematic racism and poverty. The RBG New Deal goes on to state that climate justice is racial justice and that new systems must prioritize the safety, dignity, and well-being of the most systemically divested communities in the United States. The RBG New Deal demands divestment from extractive economies and industries that harm Black lives and advocates for a sustainable future across six key pillars: Water, Energy, Land, Labor, Economy, and Democracy. One component of the plan is to “Root in the Right to Breathe” which calls for an end to toxic and polluting industry expansion in communities that have experienced environmental injustice and a shift toward prioritizing the remediation of polluted sites in those communities. It also calls for expansion of equitable access, including through improved transportation, to public health resources in historically underserved and impacted communities (Donaghy and Jiang 2021).

Scholarship that forms the basis of the RBG New Deal supports the notion that airport planning and operations represent an area of impact that could reasonably be developed as a version of environmentally just, climate responsive infrastructure that seeks redress for past harms. The RBG New

Deal is a community-driven response to social and environmental injustices. This framework and similar community-led policies depict the ways social justice and Civil Rights Movement tradition can be leveraged to conceptualize new models for equitable outcomes (Donaghy and Jiang 2021).

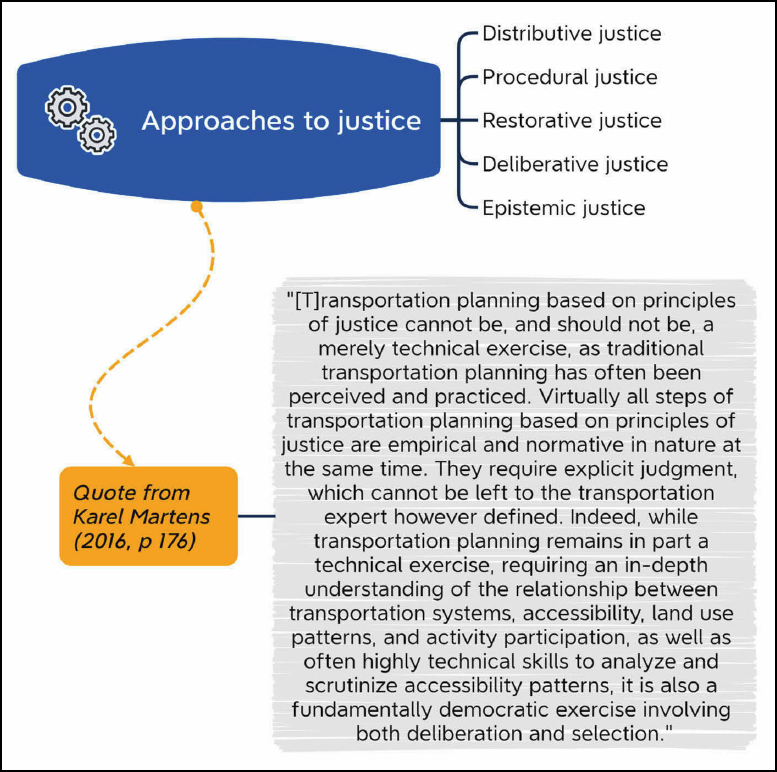

6.3 Nuanced Approaches to Justice

Equity has been broadly referred to in the literature as fairness and justice. Rather than relying on the concept of “sameness,” equity relies on a distribution of resources that achieve an even playing field (Culyer and Wagstaff 1993). This narrow definition of equity, however, still fails to address the core issues that contribute to mass inequity. For example, the structural issue of othering contributes to mass inequity but manifests even within equity-centered planning efforts (Metzger 2016). In addition, the conceptualization of the “playing field” itself is laden with value judgments on what constitutes need for resources and what constitutes “resources.” Further, access to resources is often conflated with utilization of resources, which can lead to mischaracterizations of whether an intervention actually redresses a harm or resolves a need.

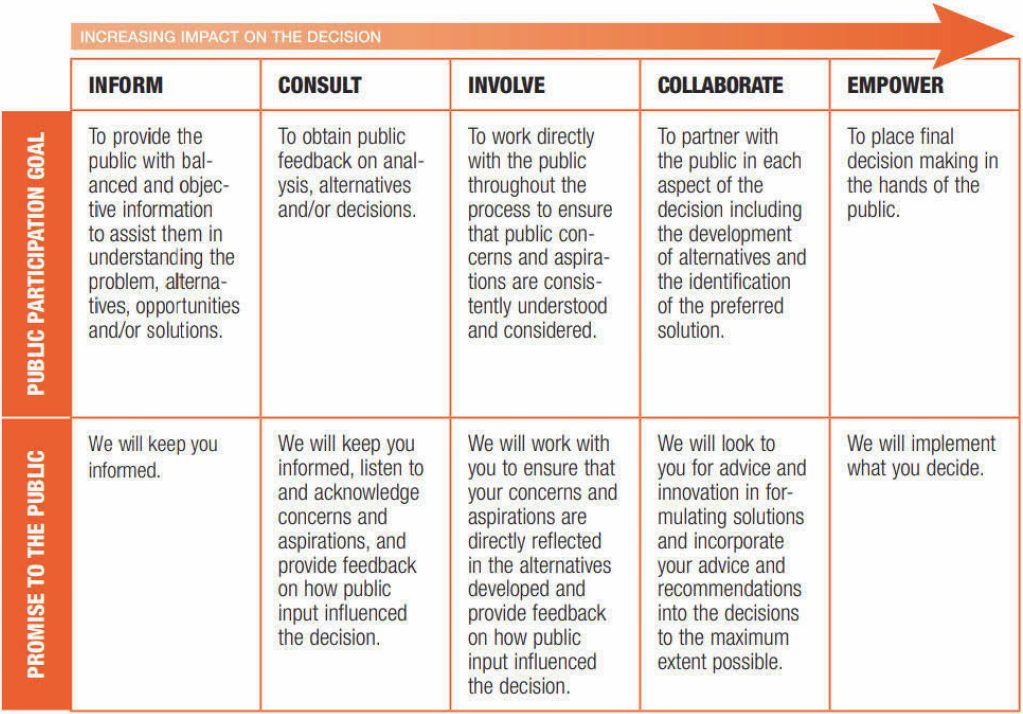

Within transportation planning, simplistic and shallow interpretations of equity have systemically produced a myriad of inequities during community engagement processes and during investment decision-making. Integrating equity and justice into airport planning and decision-making requires a nuanced effort that both specifically defines the past or ongoing harms and the aspirational future. It is also important to consider the broader context of both planning processes and planning outcomes. Key concepts within transportation equity that inform the research team’s approach to the ACRP 02-99 research are summarized in Figures 24 through 26.

This section introduces several of the nuanced definitions of justice and equity, which can be used to guide airport planning practice:

- Social justice

- Procedural Justice

- Epistemic Justice

- Distributive justice

- Transformative Justice

- Deliberative Justice

Source: The Ohio State University

Source: The Ohio State University

6.3.1 Towards Social Justice

Social justice has been described by scholars as being both an outcome and a process (Tyler 2000). In general, academic frameworks on social justice tend to explore six areas of inquiry (Tyler and Smith 1998):

- How justice and injustice inform people’s ideologies about themselves and others

- Assessing whether justice has been actualized

- How successful efforts to achieve justice inform subsequent decisions and behaviors

- The purpose and function of social justice as an aspiration

- What invokes calls for social justice

- What motivates people to strive for social justice

The academic understanding of social justice responds and sometimes reinforces systems of capitalism by placing emphasis on equitable distribution of resources and wealth and overlooking fundamental human rights. Additional core principles of social justice have been established by tradition and practice over time by the people who lend themselves to social justice movements. Those principles are

traditionally cited as equity, participation, diversity, and human rights (McDermott, Stafford, and Johnson 2021).

Intersectionality: Othering and Interlocking Systems of Oppression

An intersectional lens that considers identity, privilege, skin color, religion, clothing, and language can improve the quality of the study. Intersectionality is a theory deriving from legal scholarship, providing insight into the ways people experience society, and the ways society treats people, according to how interlocking systems of oppression show up as socially assigned combinations of identities and social markers (Crenshaw 2017). These experiences create unique modes of discrimination and privilege that are endemic in all systems and structures. The research applied an intersectional analysis to assess the wide range of inequities experienced by way of racialization and othering to provide a “new vantage for the possibilities of social change” (Collins 2019).

Given the broad body of equity-related scholarship, particularly scholarship focused on the processes of racialization, it is evident that people and communities experience racialization. Racialized experiences are informed by systemic and social responses to the identity markers that individuals carry. The ways in which identity markers come to be and are defined are inconsistent and unreliable in terms of factual, measurable realities; yet those identity markers create dominant ideals that inform how society, institutions, and communities are constructed and governed. Racial categories, in many ways, define how one experiences every aspect of their life (Blascovich et al. 1997).

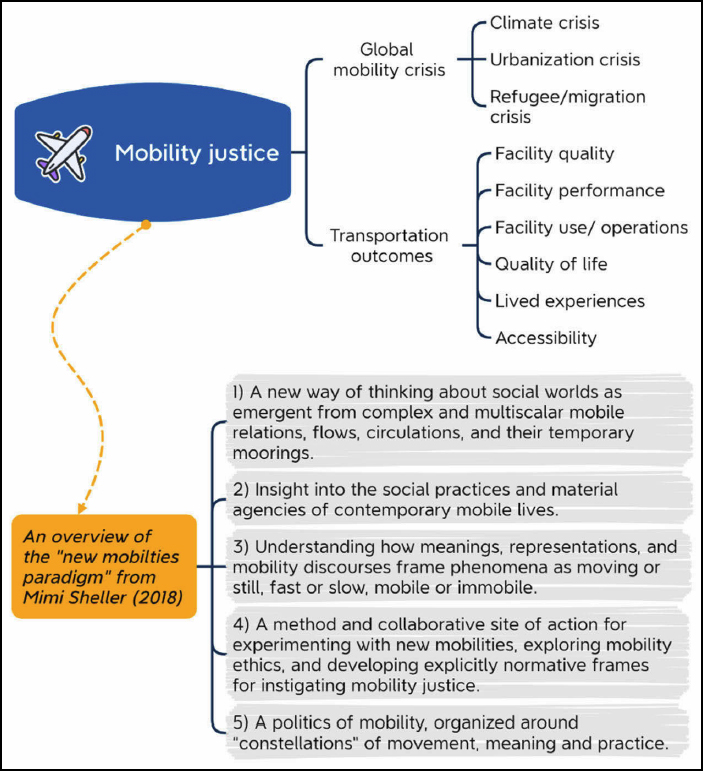

Mobility Justice: Governance and Control of Movement

Recent scholarship has explored the connection between social justice concepts and transportation planning (Martens 2017; Sheller 2018). Civil Rights Movements have been particularly influential in establishing a baseline framework for what is now considered a mobility justice movement (Cook and Butz 2019). As such, many scholars purport a mobility justice framework is an ideal model for defining equity objectives in transportation planning. As scholar Mimi Sheller explains, “mobility justice is an overarching concept for thinking about how power and inequity inform the governance and control of movement, shaping the patterns of unequal mobility and immobility in the circulation of people, resources, and information” (Sheller 2018, 14). This framing of mobility justice invites transportation planners to ask political and ethical questions about transportation systems and recognize how those systems contribute to (or detract from) freedom of movement at the individual scale, the city scale, and the global scale.

“The concept of mobility justice draws on insights from arenas such as transport justice, racial justice, and environmental justice… The promise of the new mobilities paradigm…is that it can bring together embodied movements for social justice, struggles for transport justice and accessibility, arguments for the right to the city and spatial justice, movements for migrant rights, indigenous rights, and decolonial movements, and even dimensions of climate justice and epistemic justice – all under one common framework” (Sheller 2018, 17)

As explained in her book, Sheller’s urgency to prioritize mobility justice is rooted in her understanding of the global mobility crisis, which she argues is composed of the triple threat of the climate crisis, the

urbanization crisis, and the refugee/migration crisis. The climate crisis is directly connected to mobility because the transportation sector is a leading contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions. The cyclical interplay between auto-centric land use planning and transportation demand further exacerbates these emissions over time. The damage to ecosystems and infrastructure stemming from the climate crisis causes displacement, which then contributes to transborder migration patterns. This climate-induced displacement occurs alongside the existing backdrop of the global migration of refugees from political wars, terrorism, social uprooting, and disasters. These refugees then join the mass settlement of urbanized areas, where the increase in global urbanization largely stems from the economic shift from agrarian to service economies. The heightened concentration of individuals around the world into urbanized regions is increasing the global consumption of automobility and exacerbating the ecosystem impacts of urban sprawl.

Source: The Ohio State University

Dignity as a Basis for Equity

Transportation planning that centers equity and dignity as core values represents a responsive approach to resolving inequities that persist through the legacies of the construction of race, racial capitalism, settler colonialism, chattel slavery, classicism, the continued process of othering, ableism, homophobia, and the many vast and complex systemic and structural barriers (Hess 2006). The literature shows transportation planning challenges stem from an over-reliance on quantitative indicators to define and evaluate equity (Litman 2022), and the result of this approach has been perpetually reactive

transportation planning strategies which yield outcomes that fail to address root causes of the inequities.

The notion of dignified neighborhoods describes communities that have access to places and processes whereby their subjective notions of livability are considered and accounted for in planning processes. Thinking in terms of dignity reminds planners to honor the ways each person sees themselves, how they want to feel and be, and what respect looks like from the individual perspective or lived experience (Thrivance Group 2022). Following this dignity-infused process allows individuals and communities to express their specific needs and co-create recommendations and solutions that better arrive at equitable outcomes that directly align with expressed needs.

6.3.2 Procedural Justice

Procedural justice requires practices during the planning process that allow for meaningful participation in the governance of transportation systems. Two important elements of procedural justice include access to information and agency to define the scope of deliberation. Governance decisions routinely involve scoping the legitimacy of deliberation—as in, identifying who is a legitimate participant in the decision-making process and identifying which issues are of legitimate concern to discuss as part of the decision-making process. Further, the procedures and practices of the decision-making body should be rooted in practices of dignity and respect.

6.3.3 Epistemic Justice

When considering epistemic justice in this research approach it is primarily in relation to the airport planning workforce, though it can be extended to a much broader definition of community. Epistemic justice deals with the ethics of knowledge production: Who is invited into the knowledge production process? Who is excluded? Whose knowledge is not granted respect or legitimacy? (Fricker 2007). For example, when airport planning teams lack diversity, systemic social biases can be perpetuated creating epistemic injustice in the airport planning process.

6.3.4 Distributive Justice

Distributive justice is concerned with the distribution of resources, harm, or benefits across households or individuals within a specified geography. Historically, the racialization of geographical boundaries has not only determined political representation and governmental jurisdiction, but also defined communities’ ability to access local decision-making processes and needed resources (Ford 1994).

Similarly, geographic equity is a contemporary framework in transportation and land use planning, in which the intent is to interpret land use data such that decision-making accounts for the spatial distribution of uses, latent demand, and inefficiencies (Hay 1995). Spatial inequality refers to the allocation of resources, burdens, or outcomes related to injustice. For example, when the population of a certain territory does not receive as much (or is required to contribute more) per person than the population of another territory (Hay 1995). Territorial justice infers that provision of resources should be proportionate to the need to prevent injustices. For example, when each territory’s actual distribution of resources is proportional to their respective needs (Hay 1995). Finally, minimum standards refer to needs that must be met to avoid injustices. For example, adding spatial and temporal dimensions, minimum standards for individuals would ensure that their mobility needs can be met within a certain travel distance and within a certain maximum travel delay (Hay 1995).

6.3.5 Transformative Justice

A transformative justice approach within transportation planning should include reparative interventions across the transportation sector, and in this case the aviation industry. Reparative planning is a term that garnered increased attention in the urban planning community (R. A. Williams 2020) during the 2020 racial awakening that occurred in response to the widespread hurt and outrage resulting from the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020 (D. Thomas 2020). Reparative planning calls for interventions that center atonement, repair, healing, and acknowledgment of past harms committed against impacted communities.

6.3.6 Deliberative Justice

Deliberative justice occurs where community voices are integrated into civic forums that meaningfully affect decision-making. An important element of this effort is in recognizing the value and legitimacy of community input, and in respecting their expressions of harm and need. Another important element is in recognizing social power inequities that are inherent in the solicitation of community input and inherent in the structure of opportunities to provide input. One element of deliberative justice is the implementation of deep community engagement throughout relationship building and public outreach opportunities.

Deep Community Engagement

To protect the health, well-being, and resilience of racialized communities, meaningful community engagement and policy protections must be prioritized within transportation planning, and the aviation industry. There is a long history of planning bodies failing to equitably engage impacted communities. Commonly used community engagement practices have been accused of tokenism, and general failure to address resident fears which can lead to further mistrust and contention between impacted communities and decision-making bodies. Studies have shown that a comprehensive and inclusive community engagement strategy can predict the worst impacts and increase equitable outcomes for community members.

An intentional community engagement and outreach strategy that aims to redress historical harms will:

- Identify, acknowledge, and make efforts to redress harm for impacted communities with a racial equity lens.

- Provide the community with adequate, accessible, and reliable data and information. Equitable access to information will allow the impacted communities to acquire knowledge that increases a communities’ capacity to understand problems, assess needs, and propose alternatives or solutions (see Figure 27 below).

- Center and involve the community voice from each stage of the process by eliminating barriers to community involvement. Airports or their governing bodies should assess the best method to provide community members with compensation for time, childcare services, transportation services, meals, and translation services.

- Prioritize the involvement of the most systemically divested and impacted voices first. Efforts should be made to reach historically excluded groups such as youth, immigrants, non-English-speaking community members, caretakers, or formerly incarcerated populations.

- Empower the community to a path towards final decision-making power, and a release of decision-making power from the airport or governing body.

- Include accountability structures that prioritize transparency, communication, and written or verbal commitments from airports or their governing bodies made in engagement with communities. Ideally, an external accountability group should be established and convened to evaluate engagement practices.

Source: ©International Association for Public Participation, www.iap2.org (International Association for Public Participation n.d.)