Intermodal Passenger Facility Planning and Decision-Making for Seamless Travel (2024)

Chapter: Appendix C: Project Delivery

APPENDIX C

Project Delivery

Appendix C, a companion to Chapter 7, describes the characteristics and benefits of different models of delivering intermodal passenger facility projects, including the challenges of each. Selection of a delivery model is dependent on the unique characteristics and objectives of each project or portion of a project. Content was prepared by WSP.

Considerations When Selecting a Project Delivery Method

With a governance model in place and project planning and permitting complete (scoping, environmental evaluation and clearance, property acquisition, initial business case, and financial plan), the next step is to select a method of project delivery. As with governance models, there are numerous factors to consider including:

- Legal authority to use each delivery method.

- Risk factors, including

- Schedule risk,

- Project delivery timeline,

- Cost certainty,

- Cost overruns,

- Politics, and

- Extent of stakeholder collaboration required.

- Funding availability.

- Competitive environment.

- Delivery integration, including:

- Level of contractor involvement,

- Number of desired partnerships,

- Limiting changes between design and construction phases, and

- Integration of operations and maintenance.

The following section describes different infrastructure delivery methods with these considerations in mind. Additional resources on delivery methods are available through the American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO; https://transportation.org/) and in NCHRP Research Report 939: Guidebooks for Post-Award Contract Administration for Highway Projects Delivered Using Alternative Contracting Methods, Volume 1: Design-Build Delivery (Molenaar et al. 2020).

Project Delivery Methods

Design–Bid–Build

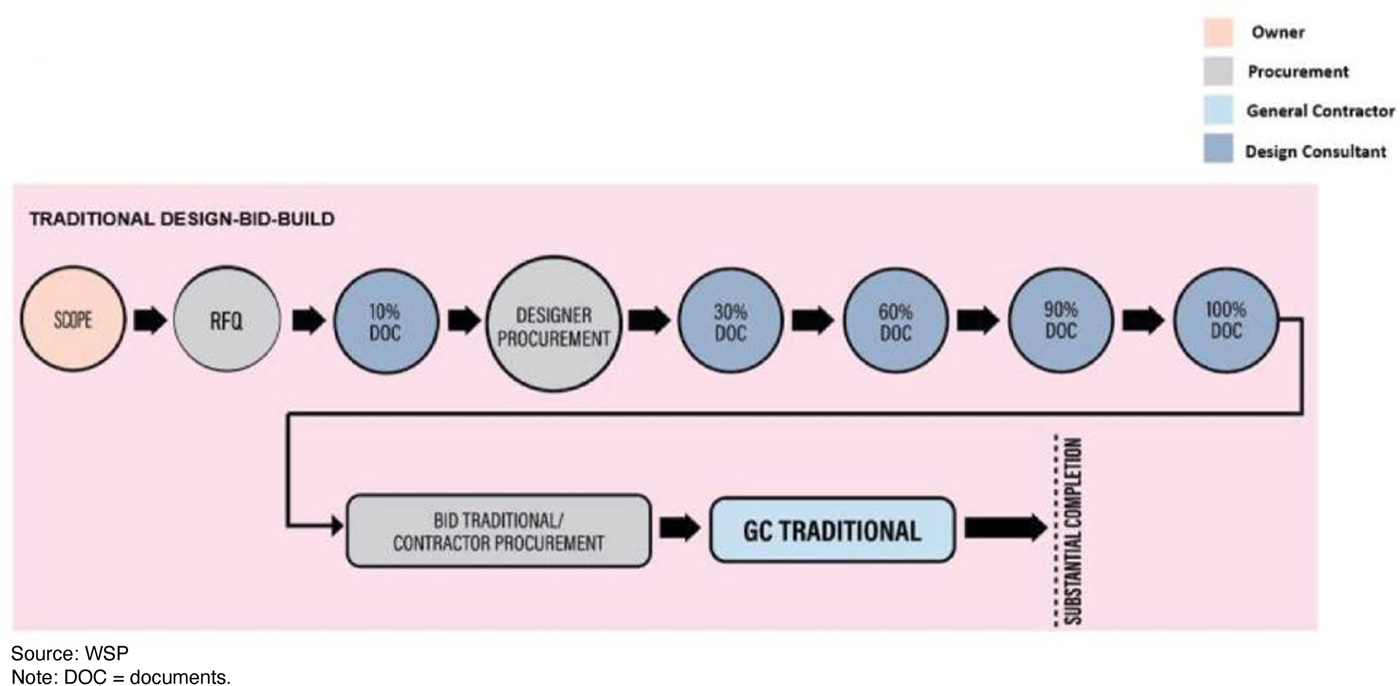

Design–bid–build (DBB) is a common method of project delivery that many government entities use. Each project phase (design and construction) is bid out sequentially through separate procurements. The public owner or project sponsor manages the interfaces between the designer and contractor. The designer develops the design and specifications to a level near 100%, and the owner uses a procurement process for the construction components. The construction contracts are bid based on 100% design drawings and specifications. In a DBB procurement, the owner assumes risks for cost and schedule. Figure C-1 illustrates the responsibilities and parties associated with a typical DBB contract.

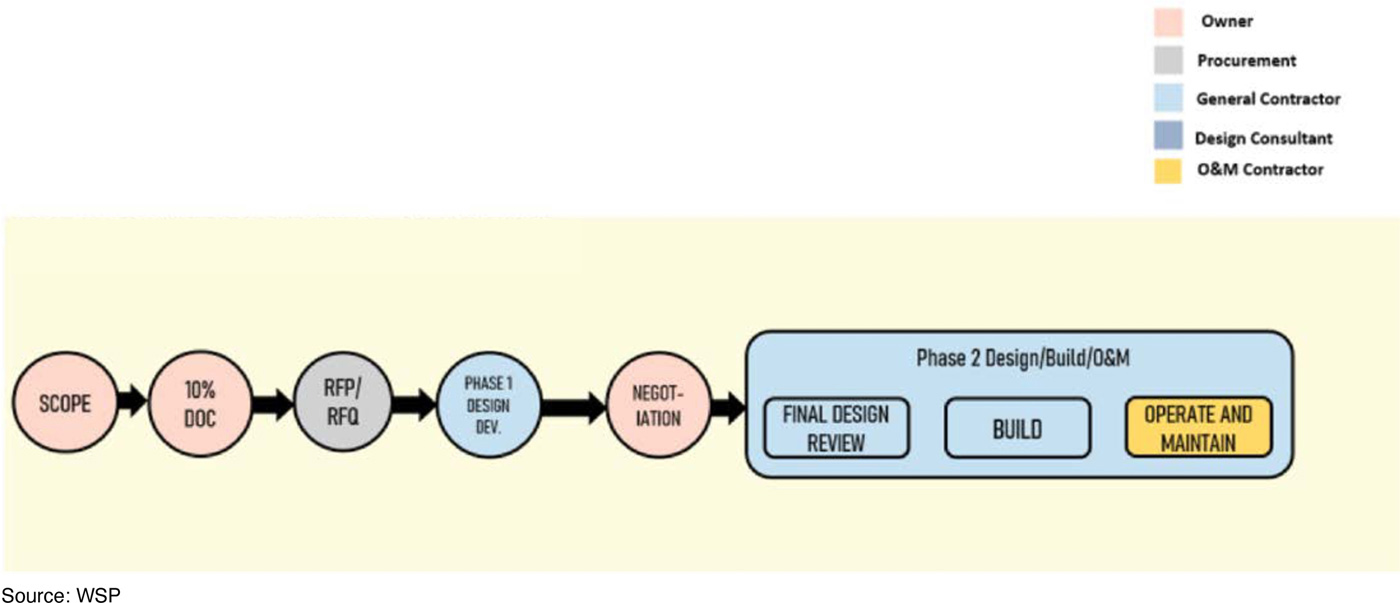

Figure C-2 illustrates a typical sequence and breakdown of how the flow of a DBB project would progress. A scope is typically determined to bring a project to 10% design. Depending on the complexity of the project, a request for qualifications (RFQ) or a request for proposals (RFP) would follow to get to full design.

Once a designer is on board, there will be interim deliverables to bring the 10% design documents to final design. At that point in the project, the public owner would begin a traditional contractor procurement process where a general contractor would be brought on board to manage the construction work to substantial completion.

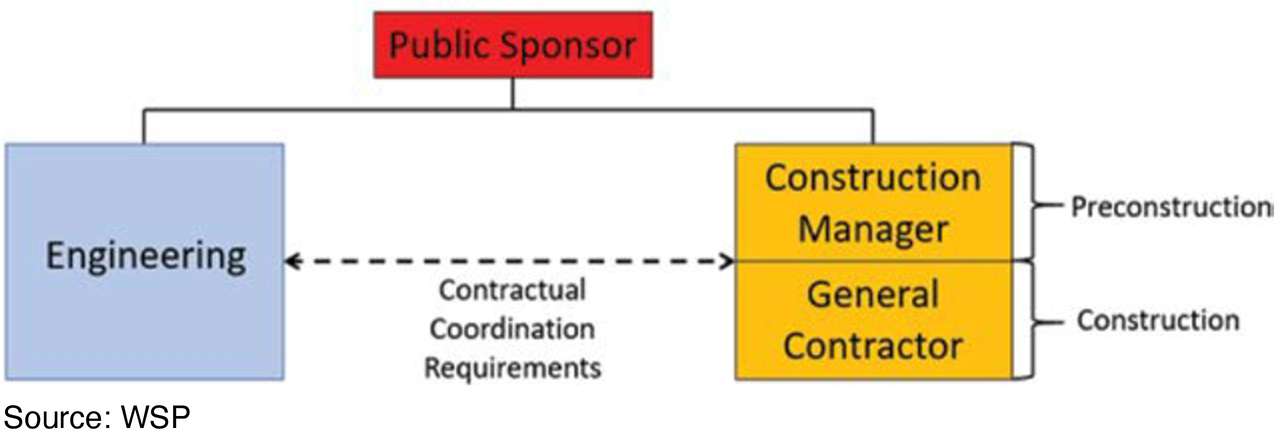

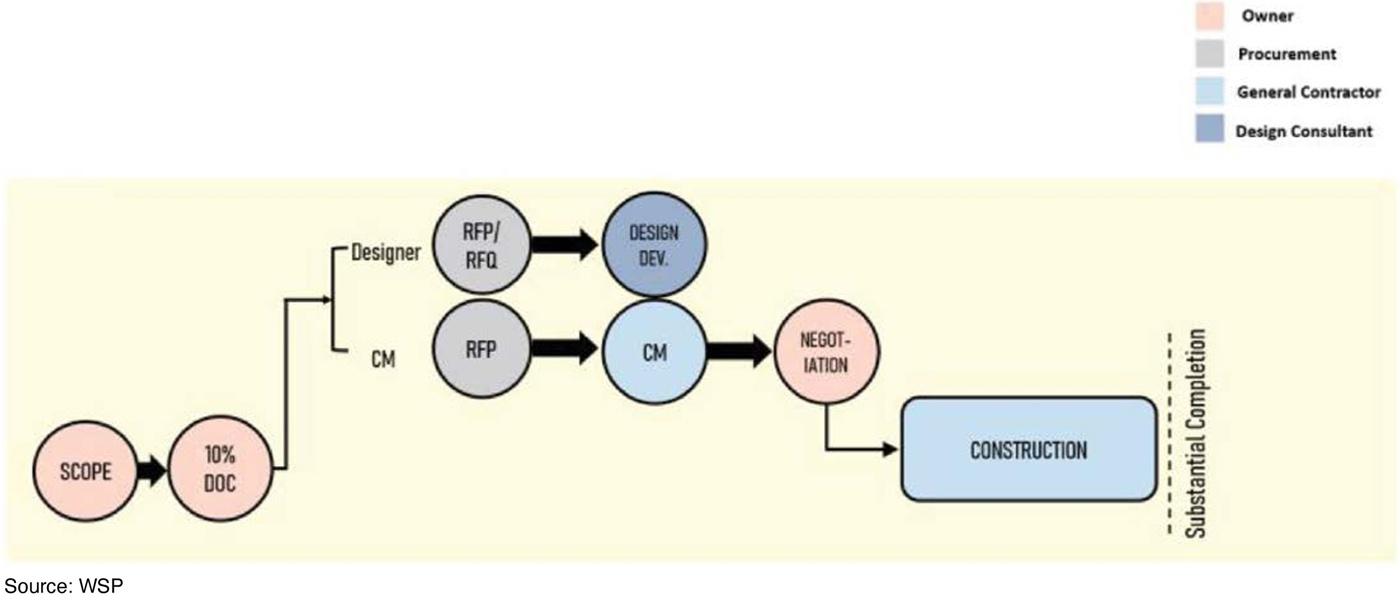

Construction Management/General Contractor

An often-used progressive delivery option is construction management/general contractor (CM/GC). This method is also known as construction manager at risk (CMAR). A CM/GC is delivered in two phases.

Phase 1: Preconstruction

CM/GC starts as the owner scopes and runs a procurement to select the designer, and the owner then conducts a procurement to select the general contractor. During Phase 1, the contractor acts as the consultant (construction manager) during the design process. The contractor

offers constructability and pricing feedback on design options and identifies risks based on the contractor’s established means and methods.

The owner is an active participant during the design process and can make informed decisions on design options based on the contractor’s expertise.

Phase 2: Construction

Once the owner considers the design to be complete, the construction manager (CM) then has an opportunity to bid on the project based on the completed design and schedule. This is the beginning of Phase 2. If the owner, designer, and independent cost estimator agree that the contractor has submitted a fair price, the owner issues a construction contract; the CM then becomes the general contractor (https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/construction/contracts/acm/cmgc.cfm). However, this method also allows the owner to select a different general contractor if the CM submits a bid that does not meet the evaluation criteria.

Figure C-3 illustrates the relationship between the owner, the engineer, and the contractor during the two phases of CM/GC, and Figure C-4 illustrates the sequence of the two phases of CM/GC.

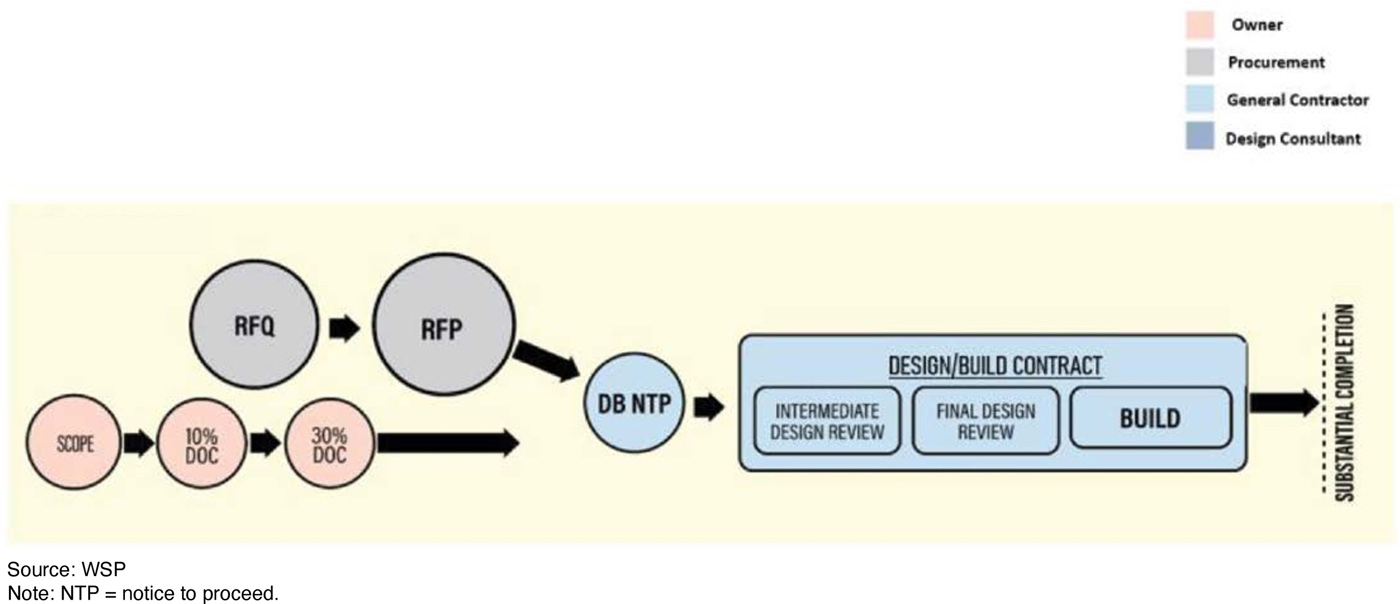

Design–Build

Design–build (DB) integrates different elements of delivery into a single contract. Project owners typically develop concept designs to approximately 30% and then initiate a procurement process to engage a contractor with design experience or a team that includes contractors and designers. The procurement process itself can be interactive by allowing bidding teams to propose alternative technical concepts and innovative solutions to reduce costs and accelerate the schedule.

This delivery method brings the contractor on early at the 30% level of design and transfers design and construction integration from the owner to the contractor. However, the level of design

requires contractors to take a larger share of risk on unknowns because of the limited design stage. This can lead to more claims and changes for the owner if unknowns are encountered during the delivery and the risk.

The DB procurement process follows these steps:

- 30% design plans developed by owner.

- Industry review/request for industry input.

- Request for qualifications.

- Select qualified bidders.

- Issue draft RFP at approximately 30% plans with performance specifications.

- Receive bidder comments.

- One-on-one meetings held.

- Alternative technical concepts evaluated (optional).

- Final RFP issued.

- Cost and technical proposal submitted.

- Contract awarded based on best value.

- Award notice to proceed.

Figure C-5 illustrates the relationship between the parties during a typical DB project, and Figure C-6 shows the sequence of a DB delivery approach.

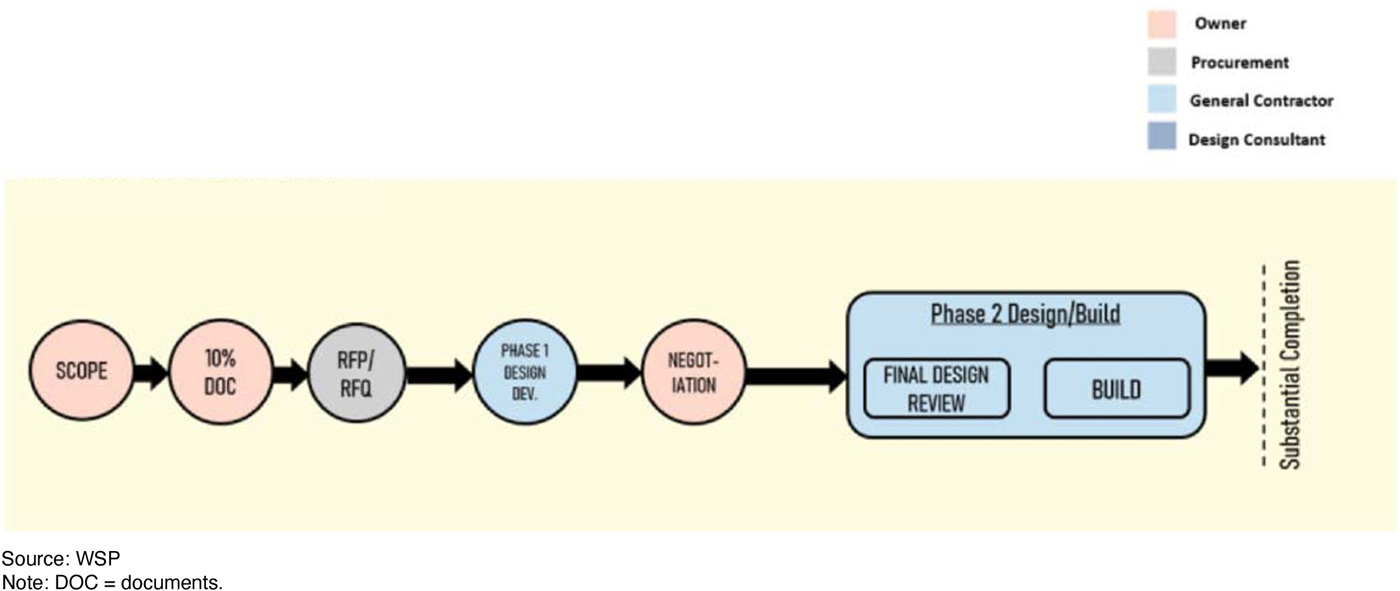

Progressive Design–Build

Progressive design–build (PDB) is gaining in popularity. As with CM/GC, under a PDB framework, the owner chooses a designer/builder based on qualifications. The relationship between parties is similar to that with a DB contract in that the designer is working for the contractor instead of the owner; however, the PDB includes two distinct phases: development and delivery.

A PDB delivery approach provides greater flexibility than a DB approach by defining and de-risking the project during the development phase. Once the project scope is defined to a sufficient detail, the PDP contractor then submits a hard bid for the delivery phase, which is negotiated with the owner on an open-book basis.

The development phase fosters an opportunity for the contractor to partner with the owner to further progress the design, determine the need for early work packages, and arrive at a more confident project cost. This method can reduce the overall delivery schedule and potential claims but has the disadvantage of the owner negotiating with a single party. Figure C-7 shows the PDB sequence.

PDB Phase Tasks

The tasks associated with each phase of a PDB option follow.

Phase 1: Development

DB services during Phase 1 are based on owner-provided design criteria and a defined scope of services, which are included with the RFP. The owner provides design criteria, basis of design documentation, and other materials, including:

- Uses,

- Space,

- Price,

- Schedule,

- Performance,

- Expandability,

- Concept design,

- Architectural guidelines,

- Design specifications,

- Standard specifications, and

- Design performance specifications.

During the proposal process, it is important for the owner to clearly define the scope and price of Phase 1 services. If the owner provides less information in the RFP, then the DB will need to develop the material during Phase 1, and Phase 1 has the potential to be open ended. Phase 1 services can be priced as cost plus, lump sum, or percentage of total project costs. The DB entity will review criteria prior to execution of the contract and confirm understanding/validity and offer innovation/changes prior to contract execution. The level of design developed during Phase 1 is dependent on the DB entity’s needs for pricing Phase 2.

To make sure the risks are addressed and the scope sufficiently defined, there are three general hold points in Phase 1:

- Confirmation of concept design.

- Confirmation of preliminary design.

- Confirmation of 50% design for pricing, including basis of design documents and schedule.

Phase 2: Delivery

Phase 2 is an amendment to the initial PDB contract where the cost is negotiated through open-book pricing at the conclusion of Phase 1. If the owner and the DB entity cannot reach agreement on the pricing, each has the option of exiting the agreement, and the contract is terminated.

During Phase 2, the DB entity performs final design reviews and constructs the project. The owner can lock certain terms and costs at the RFP phase of the PDB contract, which would then not be subject to renegotiation at the conclusion of Phase 1. These could include:

- Phase 1 costs,

- Contractor’s overhead percentage,

- Target price,

- Substantial completion date, and

- Liquidated damages.

The contract can be terminated if no agreement is reached.

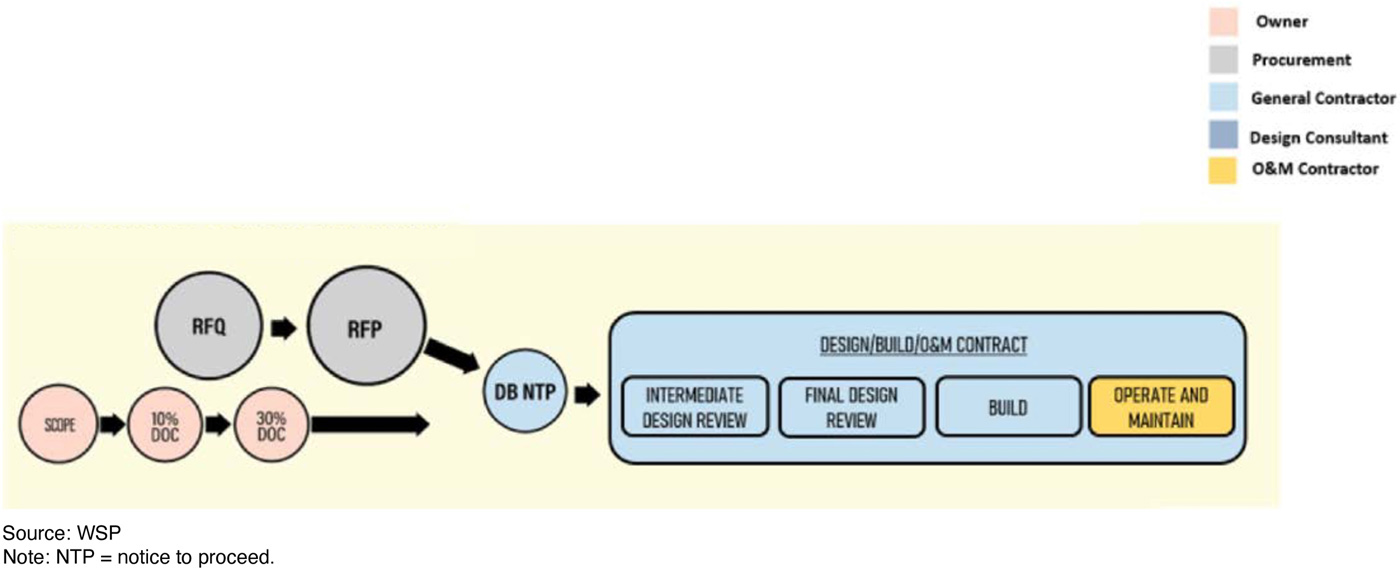

Design–Build–Operate–Maintain

In most intermodal passenger facility projects, the owner is ultimately responsible for facility operations and maintenance (O&M) and receives the facility back from the contractor once construction is complete. Under a design–build–operate–maintain (DBOM) delivery model, the same team involved with DB or PDB is also responsible for operations and maintenance over a defined period. DBOM projects typically require the contractor to meet performance measures during the O&M period to ensure that the facility is well maintained throughout the term. With a DBOM, the overall project design and selection of construction materials place greater emphasis on durability of materials to optimize life-cycle costs since the DBOM contractor is concerned with the whole life of the asset. DBOM contracts typically include risk-sharing provisions and incentives to encourage cooperation between the contractor and the owner.

This model has many advantages, including:

- O&M activities are paid for based on performance measures;

- Life-cycle concerns are considered in overall design and selection of construction materials;

- O&M can be repriced periodically;

- The facility is returned to the project sponsor at the end of the term; and

- Contracts include risk-sharing provisions and incentives to encourage cooperation between parties in a long-term partnership.

Figures C-8 and C-9 show the sequence of the DBOM and PDB with an O&M tail, respectively.

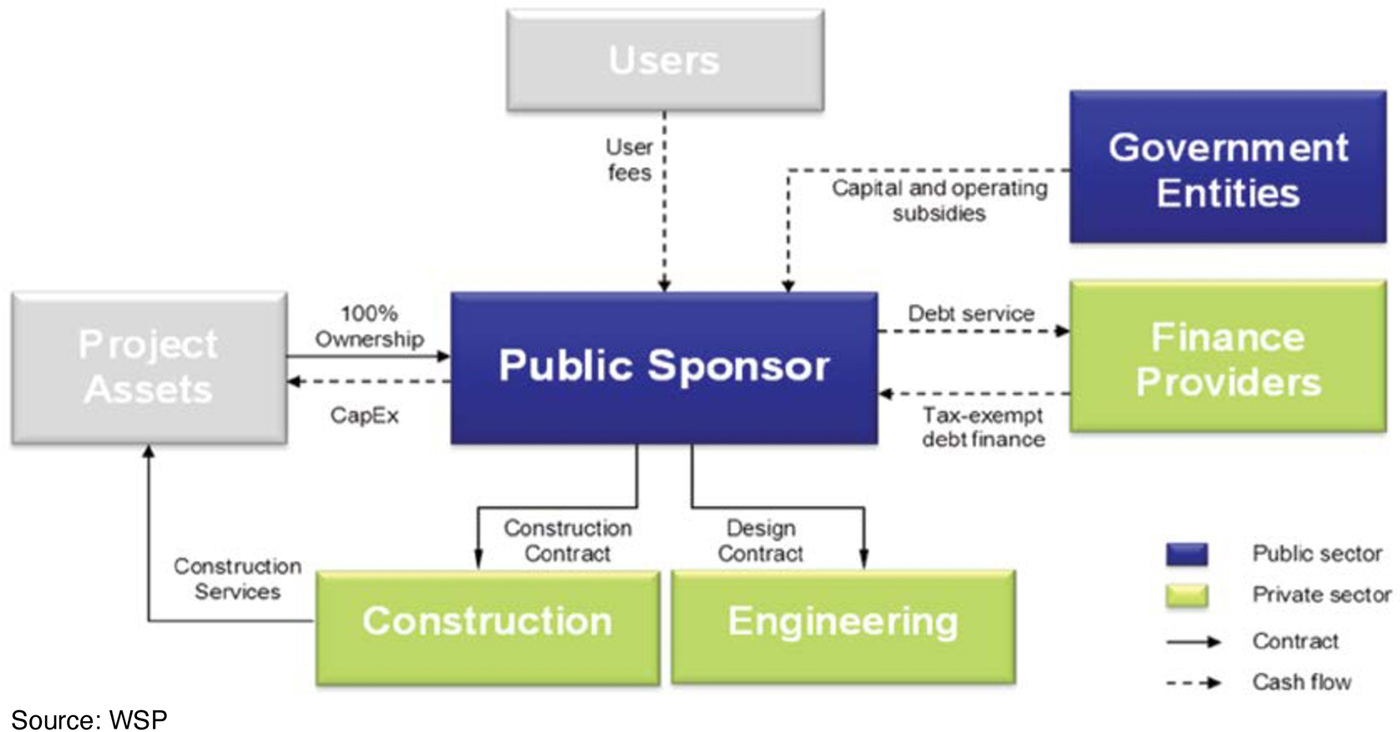

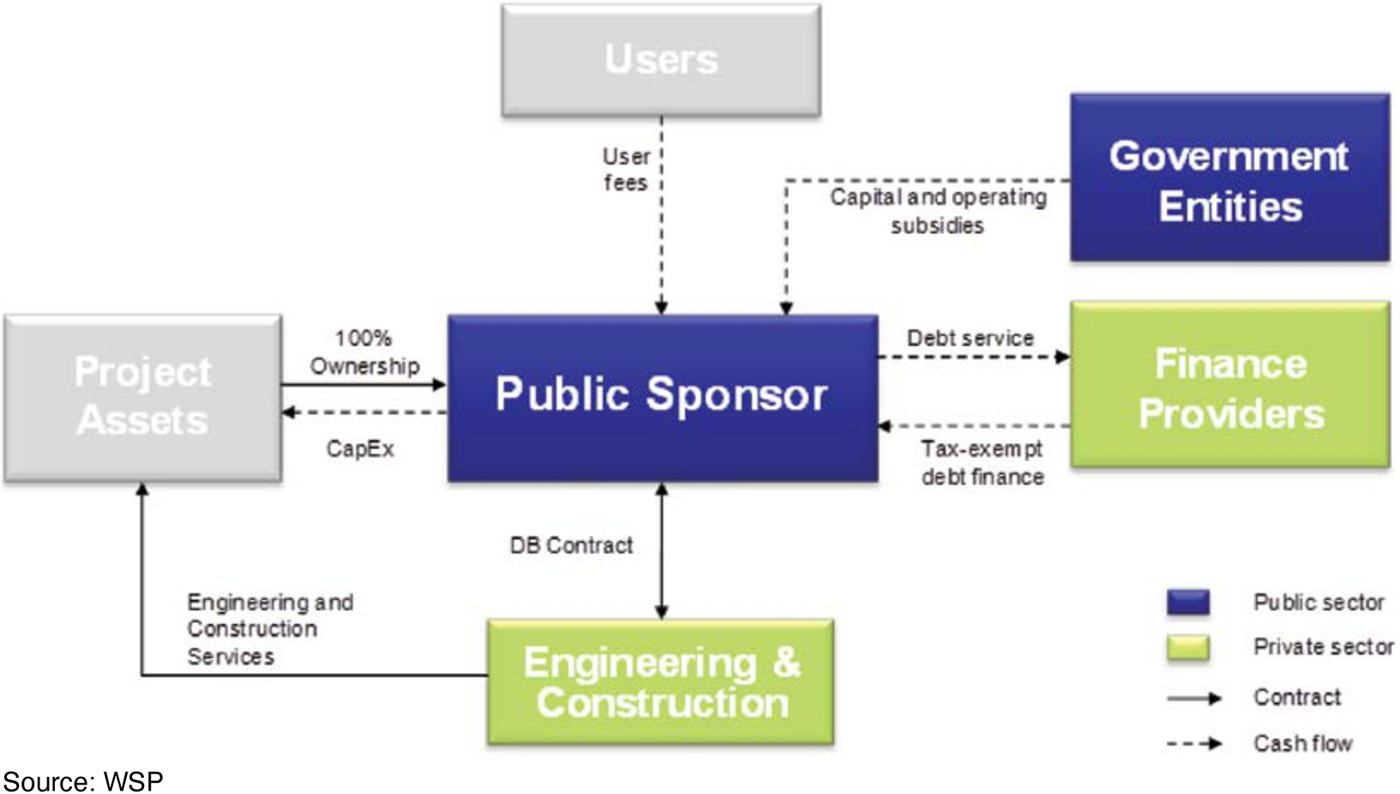

Public–Private Partnership

U.S. DOT defines a public–private partnership (P3) as a contractual agreement formed between a public agency and a private entity that allows for greater private participation in transportation project delivery and financing (U.S. Department of Transportation 2024e). All P3s include financing, operations, and maintenance.

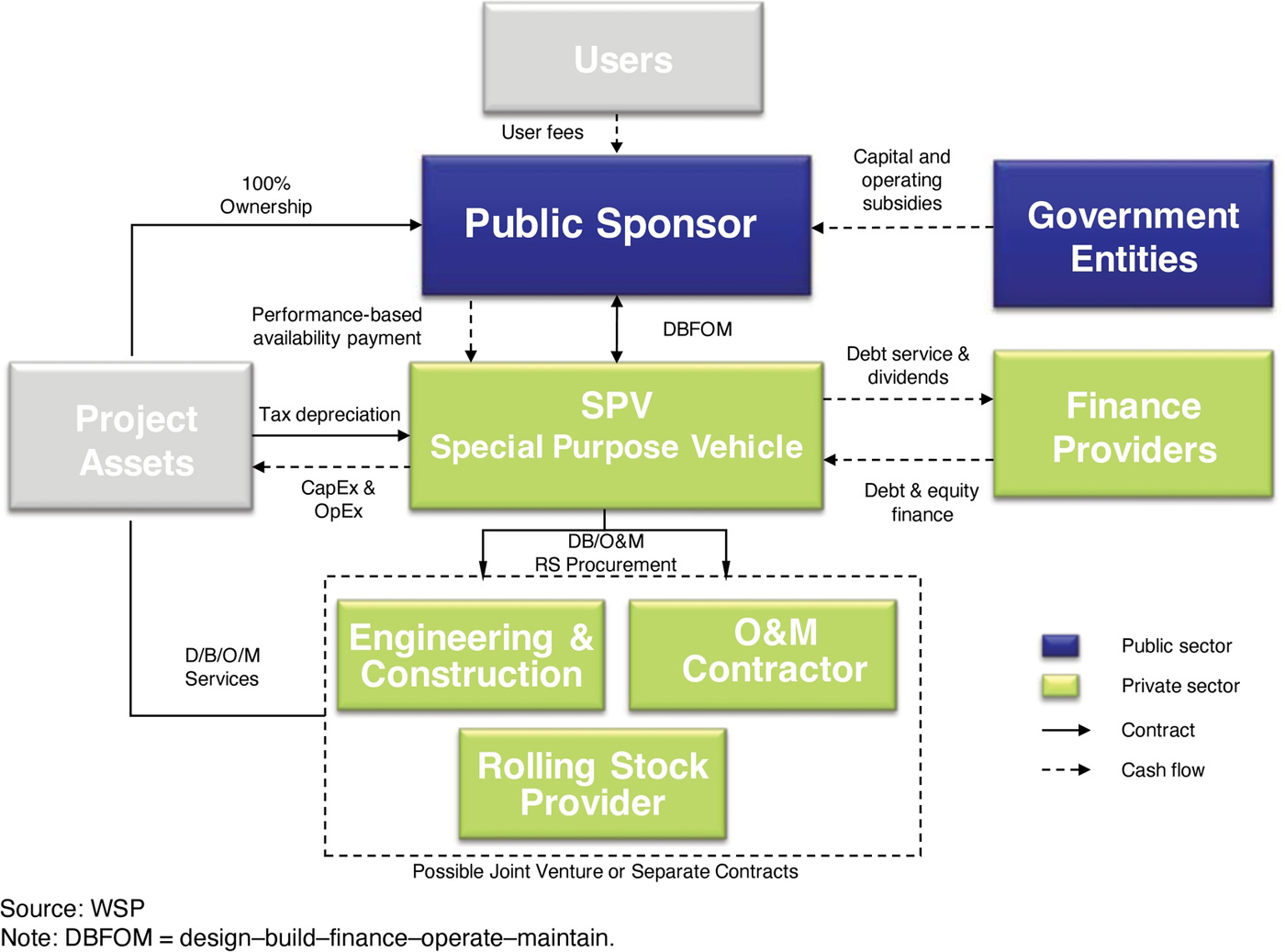

Payments under a P3 can be revenue risk, where the private partner is reimbursed with project revenue (e.g., tolls), or via availability payments, where the public owner pays the private partner back with regularly scheduled payments throughout the term. In either instance, the owner assesses liquidated damages when performance does not meet the P3 contract performance standards. The public owner can make milestone payments during the delivery phase if funds are available, thus limiting the amount of equity or financing that is required by the private sector. (See Chapter 8.)

In all cases, public sponsors procure the P3 through a transparent process that includes extensive interactions between the public owner and each private-sector proposer. The interactions include confidential discussions and proposals on design development (often including

alternative technical concepts), interactions to negotiate risk transfer and contract terms, and financial discussions to determine the best value for the owner.

Private-sector participants form a special purpose vehicle (SPV) to integrate and deliver all aspects of the project, including design, construction, operations and maintenance, and financing, and provide a single point of contact for the public owner.

The structure for a typical availability payment type P3 is shown in Figure C-10. The public owner maintains 100% ownership of the asset and makes periodic availability payments once the construction of the asset is complete. To fully gain the value of partnership, the term of a P3 contract is usually 30 to 50 years. P3s are not a form of privatization and are not sources of funding.

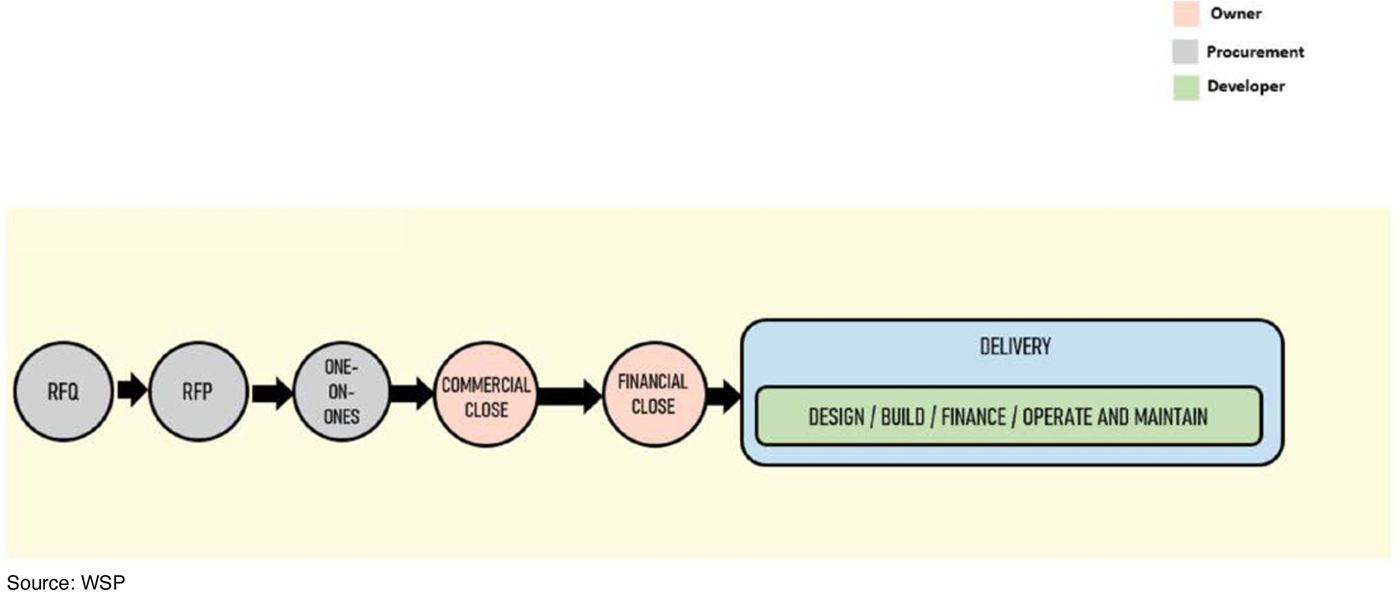

The procurement of a P3 requires expertise from public owners that they may not have in-house. It is important for public owners to have competent legal, financial, and technical advisers to assist in the development of procurement documents and throughout the procurement process. A P3 contract can take more than 2 years to procure and negotiate, but the benefits of an integrated delivery with project financing and a performance-based operations and maintenance contract can outweigh the disadvantages of a lengthy procurement time frame. Figure C-11 shows the P3 sequence of activities during procurement.

Evaluating Project Delivery Models

When evaluating project delivery options, project planners and owners should determine the legal authorities available, the goals for the procurement, and how each option meets these goals, which can include cost and schedule certainty, speed of delivery, integration of services, degree

of risk transfer, and compatibility with existing services available to the owner. The evaluation process is typically both qualitative and quantitative.

Qualitative Comparison of Project Delivery

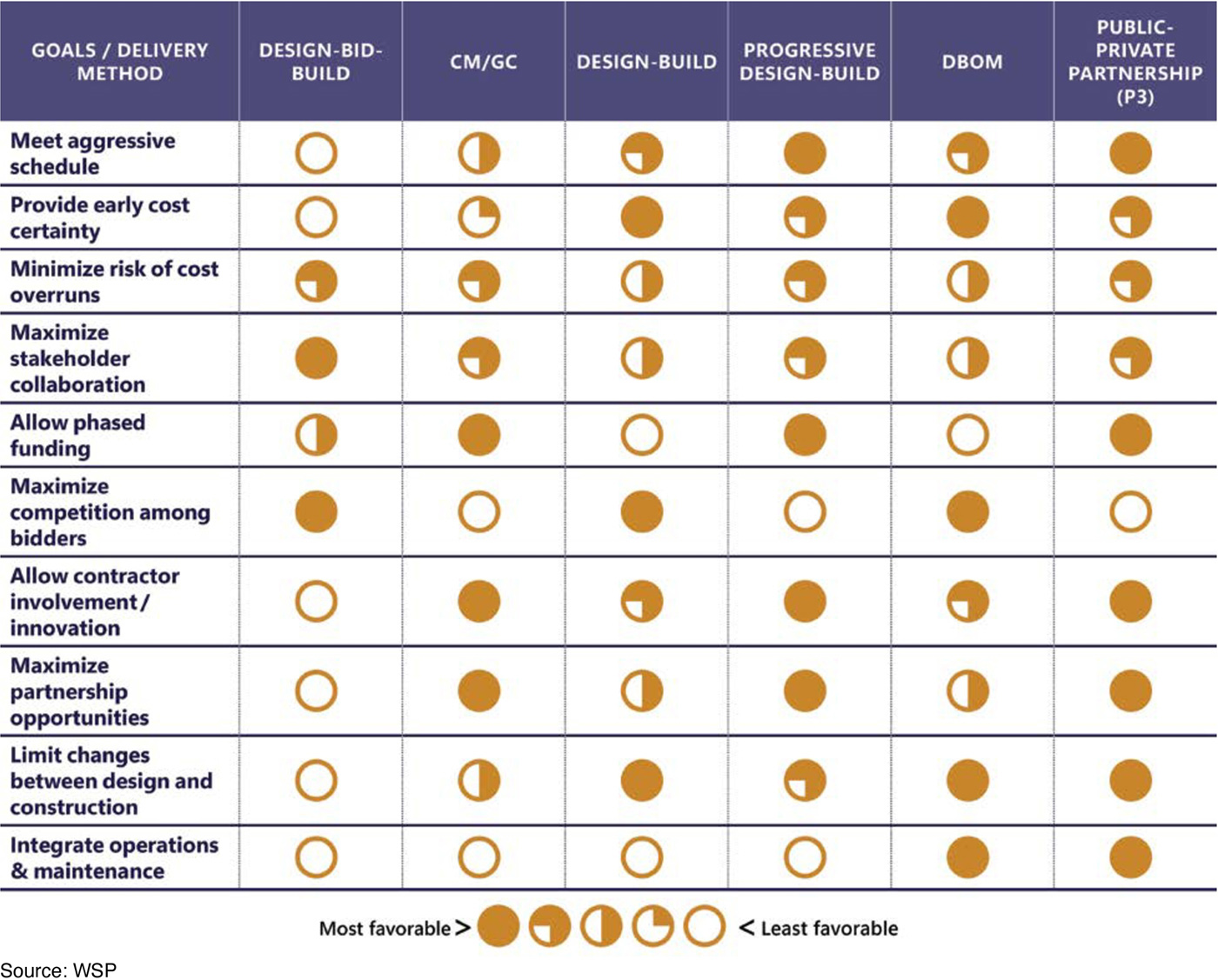

A qualitative comparison can identify necessary trade-offs to achieve stakeholder consensus. For more complex intermodal passenger facility projects, more than one delivery model may be appropriate for different project elements. For example, the redevelopment of Denver Union Station and the surrounding TOD project used a P3 for the station, while a private real estate development team redeveloped the project around the station. Figure C-12 shows, by goal category, a hypothetical evaluation using the six models discussed in this chapter.

In this example, the project goal is to quickly deliver a facility funded through facility revenue and downstream grants. The qualitative analysis indicates P3 as the most promising delivery model. P3 works in this instance because of the project’s accelerated schedule; the ability to meet the funding profile; the integration of design, construction, and operations and maintenance; the ability to enhance innovation; and price and schedule certainty. A PDB delivery option also scores well but does not include operations and maintenance services.

Quantitative Analysis of Project Delivery Options

Following the qualitative evaluation, a quantitative analysis can be used to refine the most promising options to evaluate specific project risk assessments, update cost estimates, compare schedules, and evaluate conceptual financing plans for each delivery model. It is important that the analysis receive input from identified stakeholders and that they understand their roles and responsibilities and how each delivery model will affect their workstreams and overall project governance.

Table C-1 shows the overall approach to the selection of a delivery method, including both qualitative and quantitative analysis.

Table C-1. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of project delivery methods.

| Qualitative Analysis | Quantitative Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Options | Constraints | Feasibility study | Preferred option |

| Procurement method | Stakeholder objectives | Refinement of cost and revenue estimates | Variation over phases |

| Project scope | Market appetite | Risk analysis | Risk allocation |

| Phasing | Potential public funds | Financial structure | Governance |

| Legal | Value of options comparison | Legal changes | |

| Regulatory | Range of funding need | ||

Source: WSP