Intermodal Passenger Facility Planning and Decision-Making for Seamless Travel (2024)

Chapter: 3 Recent Trends and Implications

CHAPTER 3

Recent Trends and Implications

This chapter describes trends and implications for intermodal passenger facilities from 2020 onward. It organizes the discussion into two broad categories: (1) transportation and (2) society, business, the environment, and technology.

2020 and Beyond: Remote/Hybrid Work, Climate Adaptation, and Automation

The 2020s represent a decade of continuous advances with implications for intermodal passenger facilities. Certain trends that began in the 2010s (the new mobility era) continued, but have been affected by advances in technology, changes in the private sector, climate change, and other factors.

Trends in Transportation

Growth in Telework

In August 2020, eight months after the Centers for Disease Control issued its first announcement about what became the COVID-19 pandemic, 36% of people in the United States reported living in a household where at least one person substituted telework for in-person work (Bureau of Transportation Statistics, n.d.). Some workers who began teleworking during the pandemic became remote employees, and others returned to the office on a limited basis with hybrid work arrangements.

In 2023, 12.7% of full-time employees worked from home, and 28.2% of all employees had adapted to a hybrid work model (Haan 2023). In certain U.S. cities, the share of people commuting to central business districts continues to be far lower than during pre-pandemic levels. While the number of commute trips fell, other home-based trips increased, leading to an overall increase in the number of trips nationally. At the publishing of this report, a pattern may be emerging where hybrid-eligible employees work remotely on Mondays and Fridays (WSJ Podcasts 2023).

Implications

While the future of work remains uncertain, the idea that the pandemic fundamentally reshaped work—and, by extension, commute patterns—is prevalent (Parker et al. 2022). Many transit agencies have experienced ridership declines, particularly on commuter-oriented routes, and face revenue shortfalls. This has implications for commuter-oriented intermodal passenger facilities, many of which have seen a rise in retail vacancies. While peak travel may not return to pre-pandemic levels for many years, usage patterns are likely to shift throughout the day as transit

operators adapt to different demand patterns. As of this report’s publication, this remained an area of active change and development, with an eventual steady state still uncertain.

If retail becomes a less viable use for intermodal passenger facilities, this could have implications for customers using the facilities for travel. If customers miss their connection or if a trip is canceled, passenger waiting areas that do not have amenities can diminish the user experience.

Intercity Bus Industry Disruptions

The intercity bus industry continues to evolve. United Kingdom–based First Group, which had owned Greyhound and many of its bus terminals since 2007, sold bus operations to Munich, Germany–based FlixBus and retained control of its remaining U.S. real estate holdings. First Group sold bus stations in several cities in 2020 and 2021, and in 2022, sold its remaining holdings to a private equity firm, which has since been closing additional bus stations.

Implications

The loss of more bus stations is an issue of equity and transportation access. Many intercity bus passengers have lower incomes. All passengers need safe and secure places to wait for buses and to access restrooms, food concessions, and other amenities typically found in passenger terminals. Integration of intercity bus with other modes, even beyond Amtrak and state services, will remain important but could be difficult to achieve. Partnerships and funding will be critical elements.

The Chaddick Institute at DePaul University publishes an annual outlook for the intercity bus industry. The 2023 outlook predicted continued loss of safe and comfortable places for passengers to wait for a bus, noting:

- Bus service has been relocated from bus stations to intermodal passenger facilities, train stations, convenience stores, transit hubs, curbside spots, and some airports.

- The loss of passenger facility amenities creates issues for passengers transferring late at night or early in the morning, with lengthy layovers, or during inclement weather, creating a burden on disadvantaged groups who depend heavily on bus travel.

- Bus services have been relocated to less desirable locations, sometimes outside of city centers.

- While federal regulations require funding recipients to provide “reasonable access” to intercity bus lines at public transit facilities, the fees for this access are not set in the regulations, and some of the fees being charged lead intercity bus operators to find a less costly location (Schwieterman et al. 2023).

A December 2023 Wall Street Journal article noted that the loss of traditional bus stations “highlights a plight confronting millions of travelers, many on lower incomes, that attracts far less attention than passenger rail or aviation” (Harrison 2023). The article notes, “as more centrally located bus stations close, it is not clear what will take their place. Bus operators are looking for public-sector funding to finance new facilities while some municipal officials say it is on the [bus companies] to provide safe and reliable places for riders to wait” (Harrison 2023).

Chaddick’s 2024 outlook offered the following predictions:

- Passenger traffic, now at 85%–90% of the pre-pandemic level, will fully recover by 2026—a change from Chadwick’s 2023 outlook. Driver shortages and other problems could slow the recovery, which will be uneven across regions, but the trends are favorable.

- The serious problems stemming from the closing of traditional bus stations will worsen before they get better. The accumulating effects of the closings will hurt disadvantaged populations and further hamper the image of some bus lines and bus travel generally.

- Public policies will gradually swing in the industry’s favor as the growing hardships facing disabled and lower-income travelers on long-distance trips and the success of state-supported bus systems reduce the indifference toward bus travel among many public agencies. Federal resources and new tools showcasing the importance of the U.S. intercity bus network will augment this trend.

- Improvements to the FlixBus/Greyhound, Megabus, and Trailways booking platforms will help attract new traffic. More itinerary options, reserved seating, bus-tracker tools, and other conveniences are giving consumers better choices. Still, finding the best schedule option remains far more cumbersome than for air or rail travel.

- Increases in fares will outpace inflation in the next several years, improving profit margins. Rising load factors and the strong demand for travel holiday season (for 2023) indicate that carriers will have more pricing power than in the past.

- Cooperation between Amtrak (and its state supporters) and intercity bus lines enters a new and more exciting phase as carriers and policymakers harness the benefits of further integrating these modes. Such integration will be enhanced by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act [also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL)], which will encourage states and local governments to plan for better bus and train services in tandem (Schwieterman et al. 2023).

Zero-Emission Buses and Transit Fleet Electrification

![]()

According to TCRP Research Report 219: Guidebook for Deploying Zero-Emission Transit Buses, the zero-emission bus (ZEB) market, including BEBs and fuel-cell electric buses, has begun to see growth (Linscott and Posner 2021). As of 2021, U.S. transit agencies had seen more than 1,300 ZEBs delivered or awarded, although this remains a small share of the U.S. transit bus fleet (Horadam and Posner 2022). State-level initiatives will contribute to further growth. For example, a 2020 law established requirements for New Jersey Transit to move toward 100% ZEB purchases by 2032 (New Jersey Transit, n.d.). New Jersey Transit uses motor coaches for commuter services, including trips to the Port Authority Bus Terminal in New York, for which a major terminal renovation project is underway (Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, n.d.). The project includes substantial investments in electric charging facilities for BEBs. (See discussion of Port Authority Bus Terminal project in Chapter 5.) California’s Zero-Emission Airport Shuttle Regulation, adopted in 2019, requires airport shuttle operators to transition to 100% zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) technologies (California Air Resources Board 2019).

As transit agencies respond to state mandates to convert fleets from diesel fuel, this will result in the purchase of additional ZEBs. While the shift to electrification has hit some headwinds related to charging infrastructure and vehicle cost and maintenance, the trend continues to be toward an increase in electric fleets.

Implications

The electrification of the U.S. transit fleet requires further implementation of charging facilities, and some intermodal passenger facilities will be part of the charging network. BEB charging infrastructure requires space and power and, at scale, power demands will be significant (Linscott and Posner 2021).

Digitalization/Mobility as a Service

Transit agencies and other mobility providers around the United States continue to explore mobility as a service (MaaS) platforms to support more fluid and linked transportation systems. [MaaS is also known as public mobility. See TRB Special Report 139: Between Public and Private Mobility: Examining the Rise of Technology-Enabled Transportation Services (Transportation

Research Board Committee for Review of Innovative Urban Mobility Services 2016)]. As conceived, MaaS platforms would enable travelers to plan, book, and pay for multiple transportation services in a single digital interface (Shaheen et al. 2020a). These kinds of platforms are designed to make multimodal travel seamless by shifting the burden of integrating multiple modes from the traveler to the MaaS provider (Moody and Alves 2022). Implementation of MaaS typically requires multiple agencies to coordinate unless a single provider owns multiple modes.

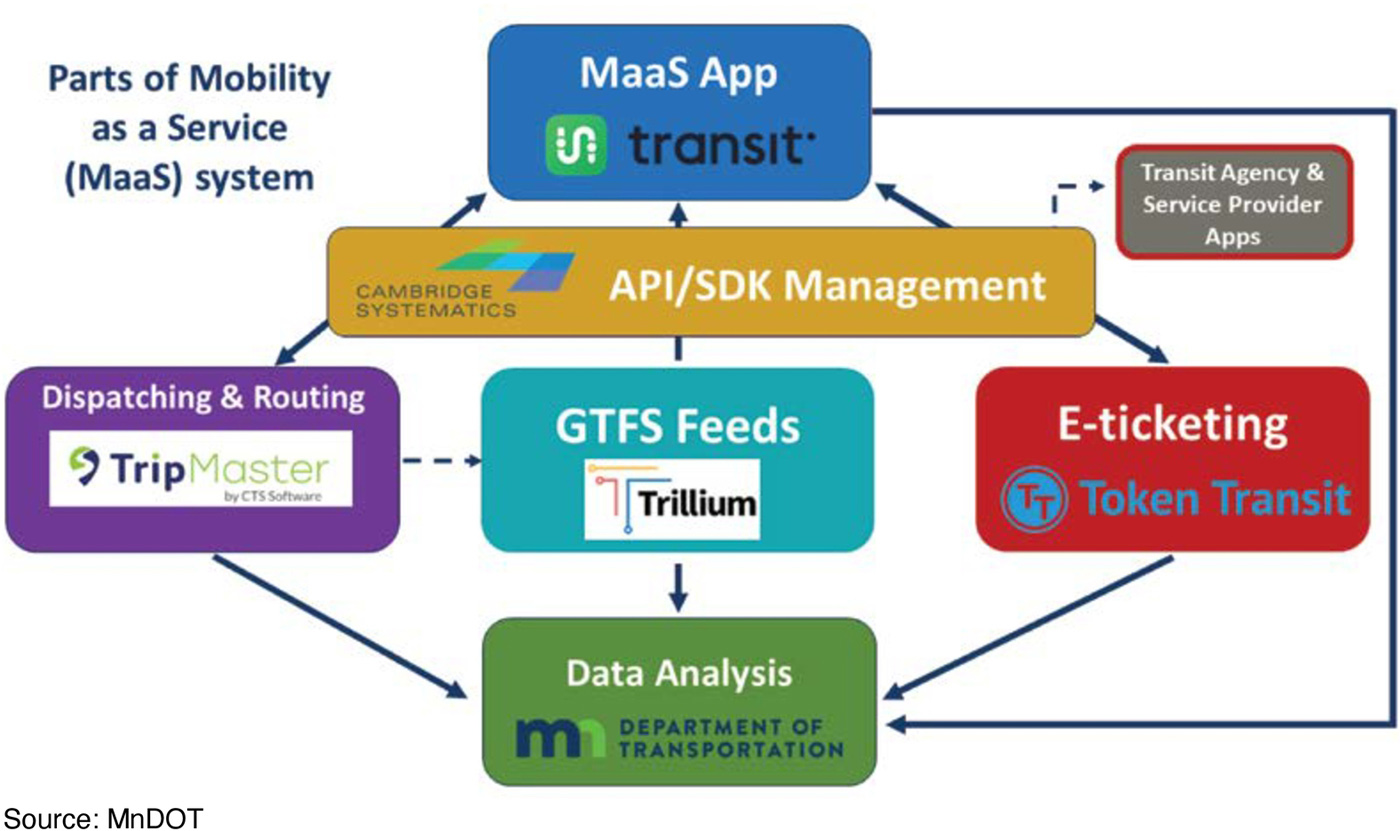

For example, the Southern Minnesota MaaS Platform Pilot Project is one example of a state-led multiagency trip planning platform and is illustrated in Figure 2. Led by the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT), the project is a collaboration of nearly 20 transit agencies and various technology vendors, including the Transit app, to create a regional trip planning platform that supports fixed-route transit, flexible transit, and paratransit, ridesharing, and micromobility (bicycles, scooters, bikesharing, scooter sharing) in southern Minnesota (Shared Use Mobility Center 2023).

In Houston, Texas, the ConnectSmart application is a multiagency partnership of transit agencies, Texas DOT, FHWA, and communities aimed at reducing the use of single-occupancy vehicles, improving safety, and reducing traffic. The mobile app provides users with available and personalized intermodal travel options and costs, transportation system updates, predictive travel times, and intermodal navigation, and it includes a mobility wallet (Texas Department of Transportation 2024).

The increase in digitization includes other transportation elements such as parking, bicycling infrastructure, carsharing, and ridehailing/TNCs. At intermodal passenger facilities, this has led to conversion of spaces for other uses and the establishment of active mobility zones, such as at airports in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Implications

While MaaS may hold promise in increasing transit travel and reducing private car use, it is still early in its development; testing of models of managing and deploying MaaS continues. To be successful, MaaS implementations must focus equally on the technical aspect of MaaS and the need for strong partnerships between municipalities, transit agencies, MaaS providers, transportation service providers, businesses, and user groups.

While its future remains uncertain, MaaS can be an important complement to intermodal passenger facilities since it supports mode connectivity for travelers. Even if not fully implemented as conceived, further integration of multimodal fare payment and intermodal transfers remains an important goal within the industry. As with other innovations, its broad adoption also raises issues of equity for certain individuals who are not fully engaged in the digital world. Having access to a smartphone, understanding how to use and navigate apps, having a data plan, and having a bank account are all barriers that will reduce or bar access for many individuals.

The increased use of digital technology will continue to transform how most customers use intermodal passenger facilities, including trip booking, navigating facilities, the check-in process, and security screening.

Shared Automated Vehicle Testing and Deployment

Shared automated vehicles (SAVs), which operate similarly to TNCs but are driverless and owned and operated by companies rather than individuals, are the subject of much discussion and debate. Perfecting the technology that enables vehicles to drive themselves under all conditions has proven difficult, so the timeline of widespread SAV deployment has repeatedly shifted in recent years (Chafkin 2022). Companies such as Waymo and Cruise began offering for-hire transportation in unattended vehicles in San Francisco and Phoenix and aimed to expand to other cities (Ohnsman 2022). The deployment of SAVs has included technical safety challenges, regulatory issues, and some erosion of public trust in companies offering SAV transportation.

While early projections of AV deployment posited them as fulfilling a wide range of use cases and transportation needs, recent deployments have pointed to a potentially more limited deployment. Much like TNCs, SAVs achieve their greatest efficiencies in denser areas where more potential riders take short trips. In less dense areas, demand is lower, requiring vehicles to travel longer distances, often without paying passengers. It is uncertain what minimum densities are necessary for SAV services, but their viability may depend on operating costs and how much riders will pay. In short, the places where these services may be most profitable are often the most congested parts of our largest cities, where transit service is more concentrated and highly competitive.

Implications

Though the future is uncertain, AVs could affect intermodal passenger facilities if and when these vehicles become widespread. Since SAVs would likely operate like TNCs, the impacts could be similar. Like ridehailing/TNCs, growth in SAVs could increase the demand for pickup/drop-off space and could increase curbside congestion as they reposition themselves after drop-offs or travel empty to pick up passengers (also known as deadheading). SAVs would also typically rely on users with smartphones who have data plans and the means to link credit or debit cards. In addition, because SAVs would operate as fleets with no driver, companies will require dedicated spaces for vehicle staging or parking and maintenance activities. It is uncertain if the growth in SAVs will then reduce car ownership or parking demand, particularly at airports, where parking is often a major source of revenue for airport operators.

Recent deployments in San Francisco have presented challenges for emergency services, including preventing AVs from entering cordoned off areas and the inability to verbally direct AVs to reposition. Such instances may present emergency management challenges at intermodal passenger facilities. Further, pedestrian safety issues prevail.

Another looming question is whether SAVs will complement or compete with transit. If the companies can lower operating costs, SAVs may meet first-/last-mile needs and extend transit’s

reach. Conversely, SAVs might directly compete with transit, affecting ridership by offering more direct connections. Studies of shared mobility services to date describe a mixed record (Shaheen et al. 2020a).

Advanced Air Mobility

Advanced air mobility (AAM) broadly refers to emerging aviation markets and use cases for on-demand and scheduled aviation in urban, suburban, and rural communities. The most recent FAA reauthorization defines AAM as a transportation system that is composed of urban air mobility and regional air mobility using manned or unmanned aircraft (Congress.gov 2023). AAM includes local use cases of about a 50-mile radius in rural or urban areas and intraregional use cases of up to a few hundred miles within or between urban and rural areas. AAM enables consumers to access air mobility, logistics, and emergency services by dispatching or using innovative aircraft and enabling technologies through an integrated and connected multimodal network across the ground, waterways, and skies (Cohen et al. 2024).

As envisioned, AAM will feature innovative technologies, such as vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) aircraft powered by electric batteries or hydrogen, and it will use both existing and new infrastructure, including airports, heliports, and vertiports (Cohen et al. 2024). Use cases include air taxis, airport feeder services, goods movement, and humanitarian assistance.

Implications

![]()

Larger airports often serve as intermodal passenger facilities where rail, air, surface, and micro-transportation options often meet. AAM presents opportunities for airports of all sizes to increase transportation services. ACRP Research Report 243: Urban Air Mobility, An Airport Perspective offers resources and tools for evaluating AAM opportunities and challenges (Mallela et al. 2023). It assesses the market opportunities, describes different business cases, and offers strategies for AAM integration. It includes a toolkit that is designed to help airport owners assess readiness and that offers resources for advancing readiness levels.

Implications for intermodal ground passenger facilities are less developed than for airports. In general, as with SAVs, the locations where AAM business opportunities would appear to be strongest are also places where operating aircraft is likely to be more difficult. New York City is a good example, where helicopter traffic is a source of public outcry (McGeehan and Gold 2021). Examples of intermodal passenger facility development for AAM include heliport redevelopment. The City of New York in 2023 introduced its vision for updating the Downtown Manhattan Heliport located at Pier 6 on the East River to include the necessary infrastructure to accommodate electric VTOL aircraft. This vision includes intermodal integrations with electric cargo bikes for coordination of maritime, air, and micro-cargo delivery (NYC: The Official Website of the City of New York 2023).

![]()

A 2024 Planning Advisory Service (PAS) report from the American Planning Association considers the community’s role in AAM. PAS Report 606: Planning for Advanced Air Mobility emphasizes the importance of learning about AAM and participating in conversations with state and federal officials. It describes potential impacts of noise, privacy, visual pollution, energy use and emissions, and land use compatibility, which could affect public perceptions of AAM and have an array of effects on communities and planning practices. It offers information on these potential impacts and how land use, zoning, infrastructure siting, and other planning and policy levers may serve as mitigation strategies (Cohen et al. 2024). Intermodal ground passenger facility owners and planners can also benefit from this participatory approach.

According to PAS Report 606, while AAM presents potential opportunities for localities, negative community perceptions could pose challenges to AAM adoption and mainstreaming.

The report also emphasizes the importance of social equity issues associated with AAM, such as affordability and who benefits from or bears the impacts of AAM, and the need to integrate AAM into existing multimodal transportation networks (Cohen et al. 2024). For new intermodal passenger facilities or existing facilities located in areas without current groundside transportation, network integrations will be a key consideration. (In this report, see Station Siting Resources in Chapter 1, Travel to and from Airports in Chapter 4, Managing Pickups and Drop-offs in Chapter 5.)

![]()

ACRP Research Report 243 offers ways for intermodal passenger facility owners to consider what to do about AAM. While focused on airports, a readiness checklist and an interactive toolkit help to address readiness for urban air mobility (UAM) activity and then make a go/no-go decision by categorizing readiness into the four levels of:

- No go,

- Not now,

- Slow go, and

- Go now (Mallela et al. 2023).

For those in all levels except no go, see Appendix A for a comprehensive discussion of AAM, including a summary of recent ACRP research, ongoing federal coordination activities, use cases, and implications for airports and other intermodal passenger facilities.

Other Transportation Trends

Growth in Private Micromobility Ownership

According to a presentation given by McKinsey and Company at the Micromobility World Conference in 2023, the private ownership of micromobility is expected to double, with the growth of shared models increasing seven times by 2025. E-scooters will also see sizable growth (Descant 2023). The growth in micromobility will likely require dedication of additional space for e-scooters and bicycles at certain intermodal passenger facilities.

Sharp Rise in Motor Vehicle and Pedestrian-Involved Crashes

According to TRB’s Critical Issues in Transportation for 2024 and Beyond, annual traffic-related fatalities grew to almost 43,000 in 2021 and 2022, about 10,000 more than in 2011. Pedestrian and bicyclist fatalities and fatality rates have also increased sharply; fatalities reached 8,300, roughly 3,300 more in 2021 than in 2010 (Transportation Research Board 2024). Prioritizing pedestrian safety at intermodal passenger facilities is especially important in pickup and drop-off zones, roadway crossings, and other areas where pedestrians and vehicles interact.

Availability of New Funding for Amtrak and High-Speed Rail

The 2021 passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) included $66 billion in additional rail funding to eliminate Amtrak’s maintenance backlog, modernize the Northeast Corridor, and invest in high-speed rail (HSR). Funded HSR projects include the ongoing Central Valley HSR project in California and a new HSR corridor between Las Vegas and Southern California. The IIJA also funds the following HSR corridor planning projects:

- Between Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia (Cascadia HSR Corridor)

- Dallas–Fort Worth to Houston, Texas

- Charlotte, North Carolina, to Atlanta, Georgia

- Antelope Valley, California

- Atlanta–Chattanooga–Nashville–Memphis Corridor

Additional projects receiving funding include new conventional rail corridors, extensions to existing routes, and improvements to existing routes (U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration 2023).

Trends in Society, Business, the Environment, and Technology

Broadening Housing Crisis

According to the 2023 Annual Homeless Assessment Report from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “on a single night in 2023, roughly 653,100 people—or about 20 of every 10,000 people in the United States—were experiencing homelessness” (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2023). Six in 10 people were experiencing sheltered homelessness—that is, in an emergency shelter, transitional housing, or safe haven program—while the remaining four in 10 were experiencing unsheltered homelessness in places not meant for human habitation (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2023).

The housing crisis, which has been particularly acute in cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco, is continuing to grow nationwide. Metropolitan areas that had enough housing in 2012 are now experiencing shortages, and the homelessness crisis is worsening as a result (Badger and Washington 2022). Increasing rent rates are also contributing to more individuals experiencing homelessness because as there is an increased likelihood of an inability to pay rent on time. During the pandemic, many states and cities established eviction moratoriums, which prevented qualifying individuals from being evicted due to unpaid rent, but as moratoriums get lifted, people that are unable to pay rent may end up in a state of homelessness.

Intermodal passenger facility owners and providers are experiencing an increase in the number of people experiencing homelessness, with impacts on vehicles, facilities, employees, service quality, and on housed passengers. This includes individuals seeking shelter within and around facilities and on transit vehicles (Zapata et al. 2024).

Implications

![]()

Intermodal passenger facilities throughout the United States have been affected as increasing numbers of people experiencing homelessness seek out shelter, safe spaces, and hygiene facilities in transportation facilities and vehicles. This is particularly acute in cities with high housing costs. TCRP Research Report 242: Homelessness: A Guide for Public Transportation describes current approaches and best practices that are responsive to people who are experiencing homelessness (Zapata et al. 2024). It identifies a range of initiatives that agencies can undertake to address the effects of homelessness on public transportation services and facilities and support people experiencing homelessness. These include partnerships with other stakeholders to jointly pursue multifaceted community goals pertaining to homelessness.

The ongoing housing crisis means that owners and providers may need to invest human and capital resources to support people experiencing homelessness. TCRP Research Report 242 dedicates a chapter to this topic, providing resources on outreach and emergency response services and activities, outlining transit agency staff roles, and identifying training in support of people experiencing homelessness.

![]()

ACRP Research Report 254: Strategies to Address Homelessness at Airports provides airports and stakeholders with resources and suggested practices to respond, in a comprehensive and humane manner, to people experiencing homelessness by working together with local communities to provide support while ensuring safety and security at the airport (Fordham et al. 2023).

Stakeholder Workshop Discussion of Unhoused Individuals

The research team conducted a workshop with representatives of transit agencies and intermodal passenger facilities. The workshop included a focused conversation on unhoused individuals, leading to the following takeaways:

- Safety, both actual and perceptual, is the most difficult aspect to navigate. Some riders may not feel safe in a station with a substantial number of individuals perceived as unhoused, and this can deter them from using the station.

- Retailers are a huge driver of image, and some stores may opt to leave a location because of high concentrations of unhoused individuals. This can make the location undesirable for other retailers. Store vacancies can diminish non-rider traffic, which can then lead to more unhoused individuals spending time in stations.

This also has staffing implications, requiring more security personnel or the creation of new positions such as restroom or track attendants. Increased staffing also means increased training, and for many of these security-related jobs, individuals require substantive training.

Extreme Weather Events and Climate Adaptation

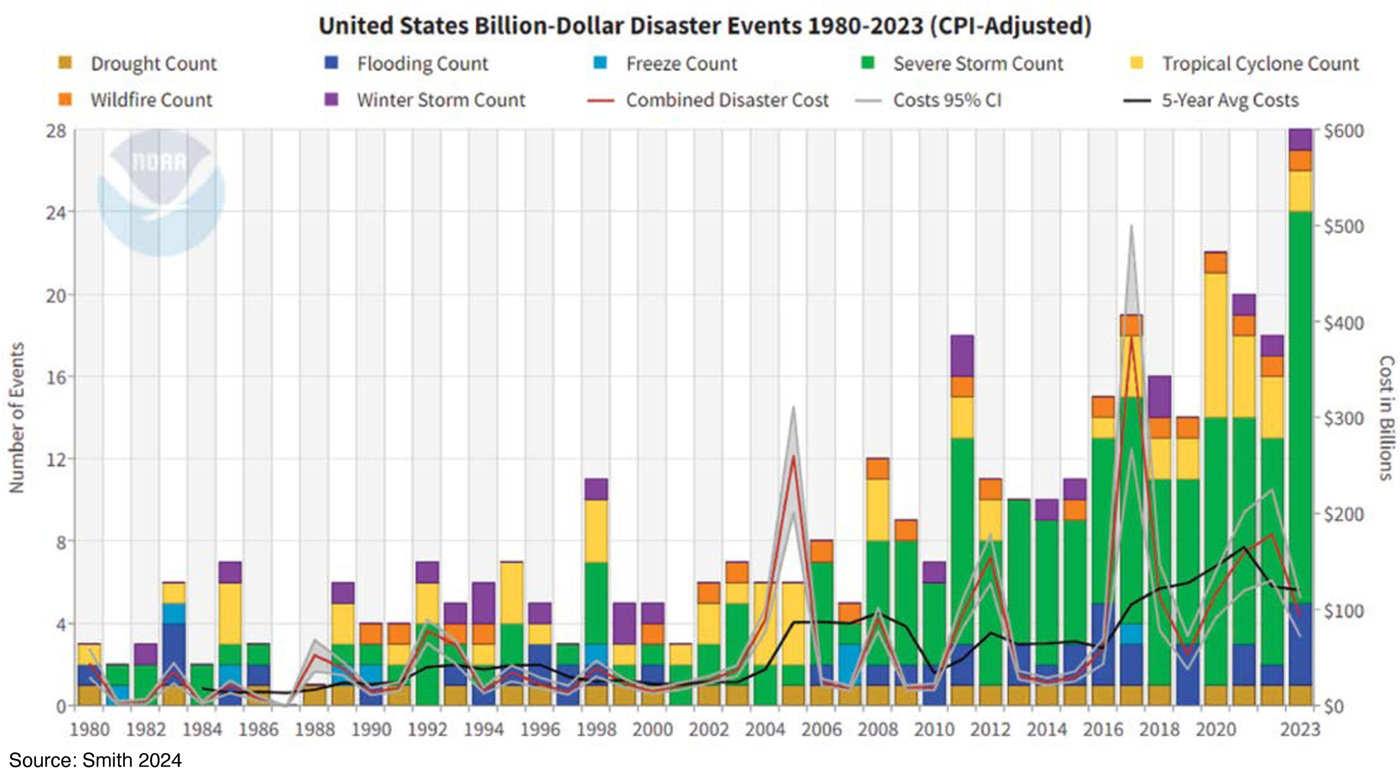

Severe storms, damaging floods and wildfires, and other extreme weather are increasing in frequency and impact (U.S. Global Change Research Program 2018). In 2023, the United States experienced 28 weather/climate disaster events, with losses exceeding one billion dollars and with 492 direct or indirect fatalities (Smith 2024). Such events are expected to increase in frequency and impact (U.S. Global Change Research Program 2018). Figure 3 presents a timeline of inflation-adjusted U.S. billion-dollar disaster events between 1980 and 2023.

Implications

Flooding, major snow events, and other extreme weather can lead to costly shutdowns and result in damage to intermodal passenger facilities, requiring costly repairs and investments in more resilient systems that can withstand and recover from disruptions.

Chronic stressors such as extreme temperature can have a cumulative, long-term impact on the infrastructure and the people who use intermodal passenger facilities. Extreme heat events can cause discomfort and a multitude of human health issues, especially when combined with humidity. Unhoused individuals often ride transit vehicles and visit facilities with air conditioning during periods of excessive heat. For more information, see the Broadening Housing Crisis discussion earlier in this chapter.

Higher temperatures and humidity can also make it harder for mechanical equipment, like air-cooled chillers and transformers, to shed excess heat, thereby leading to accelerated degradation of equipment and premature equipment failure. Warmer temperatures also greatly increase building cooling demands and associated costs, particularly for maintenance activities.

It is important to consider the risks (both the impact and consequences) of these climate-induced stressors and other risks on intermodal passengers and adjacent communities. Planning for future climate conditions is critical to ensure an optimal level of service for the users and for system performance.

Recent intermodal facility projects have incorporated resiliency planning and risk mitigation. For example, Orlando International Airport designed its new Terminal C drainage for a 100-year storm event, and recent upgrades to the San Francisco Downtown Ferry Terminal and the Colman Dock in Seattle included major investments to withstand earthquakes.

![]()

TRB Special Report 340: Investing in Transportation Resilience: A Framework for Informed Choices (Committee on Transportation Resilience Metrics 2021) reviews current transportation agency practices for evaluating resilience and conducting investment analysis and adding resilience. It presents trend data, synthesizes current transportation system resilience practices, summarizes research and analytical methods, and proposes a decision-support framework that includes asset identification, capacity and vulnerability analysis, hazard assessments, and risk assessments. Application of the framework includes stakeholder identification and cost–benefit analyses.

![]()

ACRP Report 147: Climate Change Adaptation Planning: Risk Assessment for Airports provides a guide to help airport practitioners understand the specific impacts climate change may have on their airport, to develop adaptation actions, and to incorporate those actions into the airport’s planning processes. This guide first assists practitioners in understanding their airport’s climate change risks and then guides them through a variety of mitigation scenarios and examples (Dewberry et al. 2015).

Aging Population and Growth from Immigration

Based on U.S. Census Bureau population forecasts, in the next two decades, the U.S. traveling public will consist of a significantly higher proportion of older adults (65+), with nearly one in four people projected to be an older adult by 2060 (Vespa et al. 2018). Beginning in 2030, immigration is also expected to become the primary driver of population growth (Vespa et al. 2018).

Implications

As the U.S. traveling population ages, a larger share of travelers may have mobility limitations, which in turn will increase the demand for assistance in navigating public facilities. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and state and local regulations require intermodal passenger facility planners, owners, and modal providers to design and provide accessible transportation facilities and services. For more information, see ACRP Research Report 177: Enhancing Airport Way finding for Aging Travelers and Persons with Disabilities (Harding et al. 2017).

Focus on Equity and Addressing Past Harms

Increasingly, agencies and organizations around the United States are including equity in decision-making and strategic planning efforts. This includes the U.S. DOT, which added equity as a strategic goal for the first time in its 2022–2026 strategic plan (U.S. Department of Transportation 2023b). This focus includes addressing the impacts that past transportation and other major infrastructure projects have had on disadvantaged, underserved, and overburdened communities.

Acknowledging the negative effects of certain projects, such as highways that divided communities, the IIJA includes funding for the Reconnecting Communities Pilot. This initiative aims to support efforts to restore community connectivity by removing, retrofitting, mitigating, or replacing transportation infrastructure.

Implications

Integration of equity into intermodal passenger facility decision-making includes planning, design or redesign, management, and the integration of new modes. This includes working with external stakeholders to include community groups in the planning process. (See Chapter 7.) For facilities that include intercity bus transportation, considering equity means working to integrate these services within the facility or accommodating passengers in waiting areas, offering ticketing services, and granting access to other amenities.

Considering Equity in San Jose and San Francisco

Intermodal passenger facilities can be part of a larger equity conversation. For example, a project at Diridon Station in San Jose includes raising heavy rail tracks to stitch two neighborhoods back together at the street level. As another example, the San Francisco Bay Area Water Emergency Transportation Authority (aka San Francisco Bay Ferry) lowered its ferry fares and changed its schedule to encourage more riders and change the perception that ferries are a premium product.

Continued Growth in EV Ownership

Between 2020 and 2022, U.S. battery EV sales grew rapidly, with more than 750,000 vehicles sold in 2022. As with BEBs, EV charging infrastructure, particularly rapid charging options, have been slow to develop and will take time to reach a critical mass in certain parts of the United States.

![]()

Ongoing ACRP Research Project 03-71, “Guidance for Planning for Future Vehicle Growth at Airports,” will ultimately provide information for airport operators to inventory and assess the anticipated growth in electrification needs for vehicles, aircraft, and mobile equipment.

This information will cover charging infrastructure needs, site planning, maintenance, financial considerations, resiliency, risks and hazard mitigation, and other technical, operational, and administrative concerns.

![]()

NCHRP Synthesis 605: Electric Vehicle Charging: Strategies and Programs describes strategies and practices that can help in preparation for the widespread development of EV charging facilities as the technology emerges and matures. The report explores progress and gaps in EV charging infrastructure from the perspective of state DOTs, using their experience to identify standards for future deployment of EV infrastructure (Sturgill et al. 2023).

Implications

To accomplish large-scale EV charging, facility owners will need to consider the quantity of electrical power needed, whether to purchase electricity or generate it on their own, and where to place transformers. ACRP Research Project 03-71 should provide information applicable to a broad range of intermodal passenger facilities.

EV charging for fleet vehicle and facility employees will vary by facility according to agency needs, resources, and governing policies. The demand for private passenger car EV charging is more difficult to predict. Over time, airports, future high-speed rail stations, and other intercity intermodal passenger facilities may expand access to fast chargers, perhaps in conjunction with traditional fueling stations.

Customers parking in the long term may wish to obtain a charge so they can have a fully charged vehicle on returning from travel, but such arrangements could require relocating charged vehicles to free up the charger for another vehicle. As of this report’s publication, the rental car sector’s EV commitments were in transition. In early 2022, Hertz announced it would sell about a third of its electric-vehicle fleet worldwide, or about 20,000 vehicles, in a reversal of its earlier strategy (Glickman 2024).

Use of Intermodal Passenger Facilities as Emergency Shelters

The use of intermodal passenger facilities as places to shelter people is not new. During the Cold War, many public buildings served as designated fallout shelters to be used in the event of a nuclear attack. As large public spaces with emergency power sources, certain facilities are capable of sheltering people in emergency circumstances. This has included warming or cooling facilities, evacuation centers during severe storms, and temporary housing for homeless individuals including, most recently, temporary housing for migrants when local shelters were full (Emanual 2024).

Implications

As the frequency of extreme weather (severe storms, excessive heat, or extreme cold) increases, intermodal passenger facilities can expect to see more use for temporary shelter. Owners and providers should consider establishing or expanding contingency plans for such circumstances and train personnel accordingly. They should establish or strengthen partnerships with government and community partners to ensure effective collaboration.

Summary of Potentially Important Trends

The trends discussed in this chapter represent a time of increased uncertainty, from changes in travel behavior to acceleration in technology. This combination makes it more difficult to make decisions, particularly for choices that are difficult to undo. In some circumstances, planning for flexibility may be appropriate. Table 1 summarizes ways in which transportation and other trends may affect intermodal passenger facility customers, owners, and providers. Chapter 6 offers additional suggestions on how to incorporate these trends into the decision-making process.

Table 1. How current trends may affect customers, owners, and modal providers.

| Topic | Customers | Owners | Providers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telework |

Reduced commuter foot traffic. Potential negative perceptions toward public transportation. |

Lower retail activity. Need for more security resources. |

Reduced ridership and revenues. Less predictable demand/need to alter schedules. |

| Intercity bus station closures |

Relocation of bus boarding areas to sidewalks and other locations without amenities. Diminished user experience. |

Pressure will increase to integrate intercity bus services into facilities at affordable fees. | Need for collaboration with public entities and facility owners to find ways to serve customers. |

| MaaS and digitization and fare payment |

Improved options to plan, book, pay, and navigate. Need for fare payment alternatives for those unbanked or unable or unwilling to use digital options. |

Ongoing need to integrate and update systems and technology. Management of partnerships. |

More pressure to integrate with other platforms and to form new partnerships. |

| Shared AVs | Uncertain future and consumer adoption. | Need for agreements with municipalities and providers. | More pressure to deliver sustainable business models. |

| Bus fleet changes | Higher provider capital costs may lead to higher fares. |

Need to invest in fleet charging infrastructure. More bus layover space requirements. Reduced ventilation requirements. |

New infrastructure investments. Higher capital costs. Schedule changes to accommodate charging. |

| AAM | Potential improved connections to more remote locations, including access via small airports. |

Plan for accommodating aircraft takeoff and landing. Integration of ground access at airports without any services. |

New choices on where to invest in facilities and infrastructure. |

| Housing crisis | Concern about personal safety. |

Need to trail staff and partner with social service agencies. Increased investments in security. Creation of segmented areas (i.e., access limited to ticketed passengers). |

Need to train staff and partner with social service agencies. |

| Climate change and extreme weather | Increased demand for weather-protected spaces. |

Infrastructure upgrades. Staff training for emergencies. Use of facilities as shelters. |

Schedule disruptions. Increased contingency planning. |

| Aging population |

Increased leisure travel as baby boom generation retires. Need for more travel support services. |

Increased off-peak facility use. Demand for more travel support services. |

Demand for more travel support services. Reduced revenues from more travel at reduced fares. |

| Equity focus | More attention paid to needs of intercity bus travelers. | Investment decisions increasingly require equity evaluations. | Fare revenue risks. |

| Growth in EV ownership | Demand for charging resources when parking long term. |

Uncertainties around economics and coordination of commercial charging. Provision of space for non-revenue fleet charging. |

Decisions about investments in fleet vehicles. Meeting government or agency board mandates. |