Intermodal Passenger Facility Planning and Decision-Making for Seamless Travel (2024)

Chapter: 7 Governance and Partnerships

CHAPTER 7

Governance and Partnerships

Introduction

This chapter introduces intermodal passenger facility governance, using examples from recent projects at airports, ferry terminals, rail stations, and transit centers. It explains the essential elements of governance and the assignment of roles and responsibilities throughout the facility’s life cycle. It introduces different models of project delivery and offers an overview of private development partnerships with references to available publications about joint development.

“Governance is the act or process of governing or overseeing the control and direction of something (such as a country or an organization)” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). For intermodal passenger facilities, governance typically involves multiple entities supported by strong partnerships. Effective governance and partnership agreements incorporate flexibility throughout the facility’s life cycle and reflect the local stakeholder environment. Ineffective governance can contribute to project delays, cost overruns, legal disputes, and other negative impacts. Identifying the right governance model at project inception is an essential first step in project planning and sets the stage for positive outcomes.

Types of Governance Models

![]()

Different governance models are available for delivering, maintaining, and operating intermodal passenger facilities. The choice of model used often depends on local circumstances, types and scales of project delivery efficiencies, financing plans, and legal authority. The main types are:

- Single public entity,

- Public entity cooperative agreement,

- Public and joint powers authorities, and

- Special purpose vehicles and public–private partnerships.

Single Public Entity

When one entity owns an intermodal passenger facility and provides services directly or through vendors, its governance follows the entity’s internal processes and procedures. The single entity can make all decisions and negotiate all agreements. In single public entity formats, partnerships tend to be internal. (See Coleman Dock example text box.)

Public Entity Cooperative Agreement

A public entity cooperative agreement involves two or more agencies that have distinct processes and procedures. Such agreements typically cover approaches to project funding/financing,

Single Public Entity: Coleman Dock

Washington State Ferries, a division of Washington DOT, began replacing the aging Seattle Coleman Dock in 2017 to enhance the ferry terminal’s role as a regional multimodal transportation hub. Improvements include a new 1,900 passenger terminal, elevator access and other accessibility improvements, elevated pedestrian walkways, and an elevated connection across Alaskan Way via the Marion Street Walkway to/from Downtown Seattle.

See the project website (https://wsdot.wa.gov/construction-planning/search-projects/ferries-seattle-multimodal-terminal-colman-dock-project) for more information.

delivery, and performance and may include identifying how roles and responsibilities are allocated and whose processes and procedures will govern the distinct phases of the asset’s life cycle.

Public and Joint Powers Authorities

For more complex projects or programs that may involve multiple entities, governments often establish public authorities or joint powers authorities through legislation to develop and maintain public infrastructure. Such authorities may receive public funds, directly finance projects, and procure goods and services. Public authorities provide a single point of accountability and clear policies, processes, and procedures for making decisions throughout a project’s life cycle. Public authorities also include procedures and policies to ensure transparency, accountability, and oversight, often reporting to a board made up of representatives of the partnering organizations. (See Greater Orlando Aviation Authority and Transbay Joint Powers Authority examples text box.)

Special Purpose Vehicle and Public–Private Partnerships

The U.S. DOT defines a public–private partnership (P3) as a contractual agreement formed between a public agency and a private entity that allows for greater private participation in transportation project delivery and financing (U.S. Department of Transportation 2024e). All P3s include financing, operations, and maintenance. See Appendix C for a more detailed discussion of using a P3 for delivering an intermodal passenger facility project.

Public–Private Partnership: LAX People Mover Station

The LAX People Mover connects the airport with a new Metro station, airport parking garages, and a new consolidated car rental facility. The project was developed under a P3 delivery model. Agreements among L.A. Metro and individual airlines delineated responsibilities for limits of the developer’s work and those of other entities. The private developer is responsible for delivering and financing infrastructure, including the people mover system and its operations and maintenance. See the LAX automated people mover website (https://www.lawa.org/transforminglax/projects/underway/apm) for more information.

Public Authority: Greater Orlando Aviation Authority

The Greater Orlando Aviation Authority (GOAA) oversees airports in Orlando, Florida. As part of the new Orlando International Airport Terminal C expansion project, GOAA leased three platforms to Brightline, an intercity passenger rail line serving destinations in Florida. Brightline service opened at the airport in 2023. The terminal expansion project also includes a modern car rental facility with provisions for EV charging. See the Orlando International Airport press release website (https://www.orlandoairports.net/press/2022/09/13/orlando-internationals-new-terminal-c-arriving-on-schedule/) for more information.

Joint Powers Authority: Salesforce Transit Center

The Transbay Joint Powers Authority (TJPA) has primary jurisdiction for financing, design, development, construction, and operation of the Salesforce Transit Center (Transbay Terminal). Led by an eight-member board, TJPA was created by the City and County of San Francisco, the Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District, the Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board, the California High Speed Rail Authority, and Caltrans (ex officio).

See the About TJPA website (https://tjpa.org/tjpa/about-the-tjpa) for more information.

Essential Elements of the Governance Process

Regardless of the model chosen, successful governance of intermodal passenger facilities is built on a shared vision, identification of partners and stakeholders, and clearly defined stakeholder relationships.

Establishing a Shared Vision

![]()

Establishing a shared vision with potential partners and stakeholders is a critical first step in the planning and development process. TCRP Report 102: Transit-Oriented Development in the United States: Experiences, Challenges, and Prospects (Cervero et al. 2004) and TCRP Report 224: Guide to Joint Development for Public Transportation Agencies (Raine et al. 2021) provide examples of projects with shared visions.

As an example, for Arlington County, Virginia, maintaining a focus on its shared vision was critical to successful TOD implementation. Through a process that encompassed multiple stakeholders in the early 1970s, the county adopted a bull’s eye metaphor to articulate its TOD goal (Cervero et al. 2004). This enabled the county to leverage Metrorail’s presence and transform once dormant neighborhoods into vibrant clusters of office, retail, and residential development. The original vision and subsequent general plan and station area plans contributed to the realization of that vision. The county’s ability to promote and sustain growth for over 40 years is the result of maintaining the original vision while adapting to the changing needs of its communities (Cervero et al. 2004).

Identifying Partners and Stakeholders

Strong coordination among partners and stakeholders is paramount to a successful intermodal passenger facility, particularly those that feature multiple modes of transportation and

service providers. Each mode or service may have unique public or private stakeholders. Categorizing partners and stakeholders helps to clarify roles and responsibilities, which are then reflected in governance processes and procedures. Partners and stakeholders generally fall into three categories: direct participants, consulting parties, and external stakeholders.

Direct Participants

Direct participants include public entities with direct responsibility for the facility, and they typically include the property owner, a major tenant or operator, a major service provider, or public agencies with authority over the facility. Direct participants, either singly or jointly, have roles in governance and have ultimate decision-making authority. The direct participants’ roles and responsibilities are codified through legal agreements, partnership agreements, contracts, or legislation.

Consulting Parties

Consulting parties may have a role in project delivery or facility management but are not involved with decision-making. Examples of consulting parties are public agencies with review or permitting roles, project abutters, public safety agencies, contractors, project tenants, and modal operating agencies. Agreements with consulting parties may take the form of contracts, cooperative agreements, interface agreements, memorandums of understanding, and operating agreements. These flow from the authority of the direct participants.

External Stakeholders

External stakeholders are public and private entities with an outside interest in an intermodal passenger facility. External stakeholders include community organizations, neighborhood or business associations, and advocates. Intermodal passenger facility projects need well-established plans for external stakeholder communication. Appointed project advisory committees are often used for this purpose. In some instances, specific communication protocols can be established between the primary participants and the external stakeholders to outline the types and schedules of communication.

Defining Stakeholder Relationships

The process of defining stakeholder relationships typically begins with mapping all facility stakeholders and grouping them into functional categories, such as owners, customers, transportation providers, service providers, and community groups. Figure 8 illustrates a mapping example for airport stakeholders that is derived from the International Air Transport Association (IATA) Airport Governance Toolkit (Reece and Robinson 2020). This comprehensive example helps to illustrate parties directly involved in an airport (e.g., facility owner, airlines, owners), consulting parties (e.g., government and related entities), and external entities (e.g., communities). The mapping process in this example also considers other important stakeholders, such as consumers and passengers, modal providers (airlines and surface transportation providers), and retail tenants.

Assigning Roles and Responsibilities

![]()

Because intermodal passenger facility projects often involve several public and private entities as well as external stakeholders, project planners should address certain key questions while defining relationships, roles, and responsibilities, including:

- Who has the legal authority to participate in the project? Is a legislative change required to include the pertinent parties?

- Who can provide funding for the project? Is financing available and by whom? Can equity/revenue flow to the project and, if so, through what party?

- Who has property rights, including land ownership, leases, and development rights?

- Whose regulations and standards will apply and who has oversight?

- Who will sustain and maintain the project through its life cycle?

- Who has responsibility for safety and security?

For governance purposes, entities identified through this initial set of questions are then typically divided into direct participants, consulting participants, and external stakeholders.

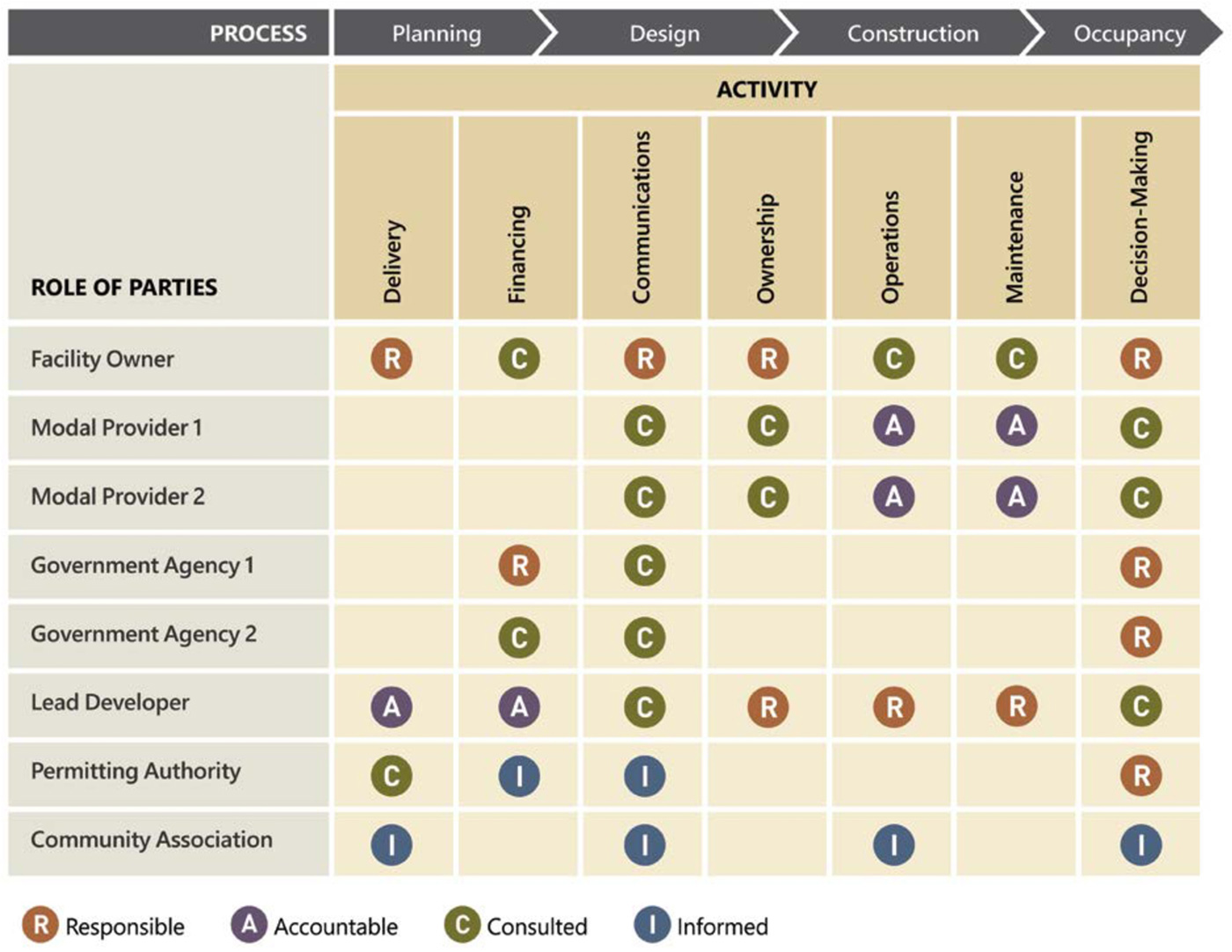

Using a RACI Matrix to Assign Roles and Responsibilities

![]()

RACI (responsible, accountable, consulted, informed) is an acronym for a type of responsibility matrix specifying who is responsible for a task, who is accountable for a task, who needs to be consulted, and who needs to be informed. A RACI matrix is helpful when projects have multiple participating entities performing different tasks that feature multiple timelines, key milestones, and decision points. RACI is commonly used for managing different types of construction, implementation, and monitoring activities (AASHTO 2024).

![]()

A RACI matrix or other matrix approach can help inform the structuring of governance agreements. Once roles and responsibilities are established, legal agreements, contracts, and legislation can be developed to formally establish the relationships among the parties. Figure 9 presents an example for a hypothetical intermodal passenger facility.

Accommodating Changes Over a Project’s Life Cycle

Stakeholder roles and responsibilities may evolve as a project moves from inception to delivery to operations and maintenance. Governance models should take into consideration the full life cycle and what roles each party may play at different times. Flexible governance agreements consider the different roles parties may play during planning, design, construction, and operations and maintenance phases of the project. In addition, the governance model should be flexible and designed to accommodate potential changes in roles and responsibilities.

Governance Model Checklist

![]()

A governance model should address all aspects of the intermodal passenger facility, from planning and delivery through operations and maintenance. Once a model that clarifies roles and responsibilities is created, governance agreements can be created. Regardless of the model of governance, all governance agreements should include these elements:

- A statement of the shared vision for the project and its objectives.

- An outline of the relationships between all internal and external partners and stakeholders and those with property interests.

- A formal agreement among the direct participants that identifies a structure with a single point of authority for decision-making.

- Authority for representing the project in contracting and working with external stakeholders and third parties throughout its life cycle.

- A preliminary financing plan that identifies sources and uses of funds, conditions for receiving grant funds or revenues, and potential for creating incentives to foster cooperative behavior. (See Chapter 8.)

- Considerations for future expansion.

- An agreement on management mechanisms for:

- Processes and procedures,

- Independent reviews and oversight,

- Dispute resolution,

- Approving changes, and

- Reporting and transparency.

Documenting the approaches to these governance framework essentials and identifying the strategies to implement them will contribute to successful project delivery and high levels of performance throughout the facility’s useful life. Spending time early in the intermodal passenger facility development process to document the approach to governance and implementing the framework is a critical first step in project development.

Flexible Governance at Denver Union Station

The Denver Union project illustrates how governance can change over time. The City of Denver originally adopted the Denver Union Station Master Plan in 2004. Four years later, the Denver Union Station Project Authority (DUSPA), a nonprofit, public benefit corporation was established to finance and oversee project implementation. Partners included Regional Transportation District (RTD), the City and County of Denver, Colorado DOT, and the Denver Regional Council of Governments. Since project completion, RTD is responsible for station elements while a private developer is responsible for the historic station building. (See Appendix D.)

Project Delivery Methods

With a governance model in place and project planning and permitting complete (scoping, environmental evaluation and clearance, property acquisition, initial business case and financial plan), the next step is to select a method of project delivery. The following discussion offers a high-level summary of available methods. Appendix C provides more details on project delivery methods, including on structures and timelines.

Design–Bid–Build

Design–bid–build (DBB) is a common method of project delivery that many government entities use. Each project phase (design and construction) is bid out sequentially through separate procurements. The public owner or project sponsor manages the interfaces between the designer and contractor. The designer develops the design and specifications to a level near 100%, and the owner uses a procurement process for the construction components. The construction contracts are bid based on 100% design drawings and specifications. In a DBB procurement, the owner assumes risks for cost and schedule.

Construction Management/General Contractor

Construction management/general contractor (CM/GC) is a progressive project delivery option. A CM/GC is delivered in two phases (preconstruction and construction). This method is also known as construction manager at risk (CMAR). This delivery method brings the contractor on at the 30% level of design and requires delivery at a guaranteed maximum price.

Design–Build

Design–build (DB) integrates different elements of delivery into a single contract. Project owners typically develop concept designs to approximately 30% and then initiate a procurement process to engage a contractor with design experience or a team that includes contractors and designers. The procurement process itself can be interactive by allowing bidding teams to propose alternative technical concepts and innovative solutions to reduce costs and accelerate the schedule.

As with CMAR, this delivery method brings the contractor on early at a 30% level of design and transfers design and construction integration from the owner to the contractor. However, the level of design requires contractors to take a larger share of risk on unknowns because of the limited design stage. This can lead to more claims and changes for the owner if unknowns are encountered.

Progressive Design–Build

Progressive design–build (PDB) is gaining in popularity. Like CM/GC, under a PDB framework, the owner chooses a designer/builder based on qualifications. The relationship between parties is like that with a DB contract in that the designer is working for the contractor instead of the owner; however, PDB includes two distinct phases: development and delivery.

A PDB delivery approach provides greater flexibility than a DB approach by defining and de-risking the project during the development phase. Once the project scope is defined to a sufficient detail, the PDB contractor then submits a hard bid for the delivery phase, which is negotiated with the owner on an open-book basis.

The development phase fosters an opportunity for the contractor to partner with the owner to further progress the design, determine the need for early work packages, and arrive at a more

confident project cost. This method can reduce the overall delivery schedule and potential claims but has the disadvantage of the owner negotiating with a single party.

Design–Build–Operate–Maintain

In most intermodal passenger facility projects, the owner is ultimately responsible for facility operations and maintenance and receives the facility back from the contractor once construction is complete. Under a design–build–operate–maintain (DBOM) delivery model, the same team involved with DB or PDB is also responsible for operations and maintenance over a defined period. DBOM projects typically require the contractor to meet performance measures during the operations and maintenance period to ensure that the facility is well maintained throughout the term. With DBOM, the overall project design and selection of construction materials place greater emphasis on durability of materials to optimize life-cycle costs since the DBOM contractor is concerned with the whole life of the asset. DBOM contracts typically include risk-sharing provisions and incentives to encourage cooperation between the contractor and the owner.

Public–Private Partnerships

P3s combine design, construction, financing, and operations and maintenance under one contract. P3s are performance-based contracts. They are often used when an owner wants to accelerate delivery of a facility and combine that with performance-based operations and maintenance over a set term. It is important to have a defined project scope, environmental clearance, performance-based specifications, and a project champion representing the owner.

P3s require expertise from public owners that they may not have in-house. Because P3s are complex, public owners should have competent legal, financial, and technical advisers in place to assist with development of procurement documents and throughout the procurement process. It can take more than 2 years to procure and negotiate a P3 contract, but the benefits of an integrated delivery with project financing and a performance-based operations and maintenance contract can overcome the disadvantages of a lengthy procurement time frame.

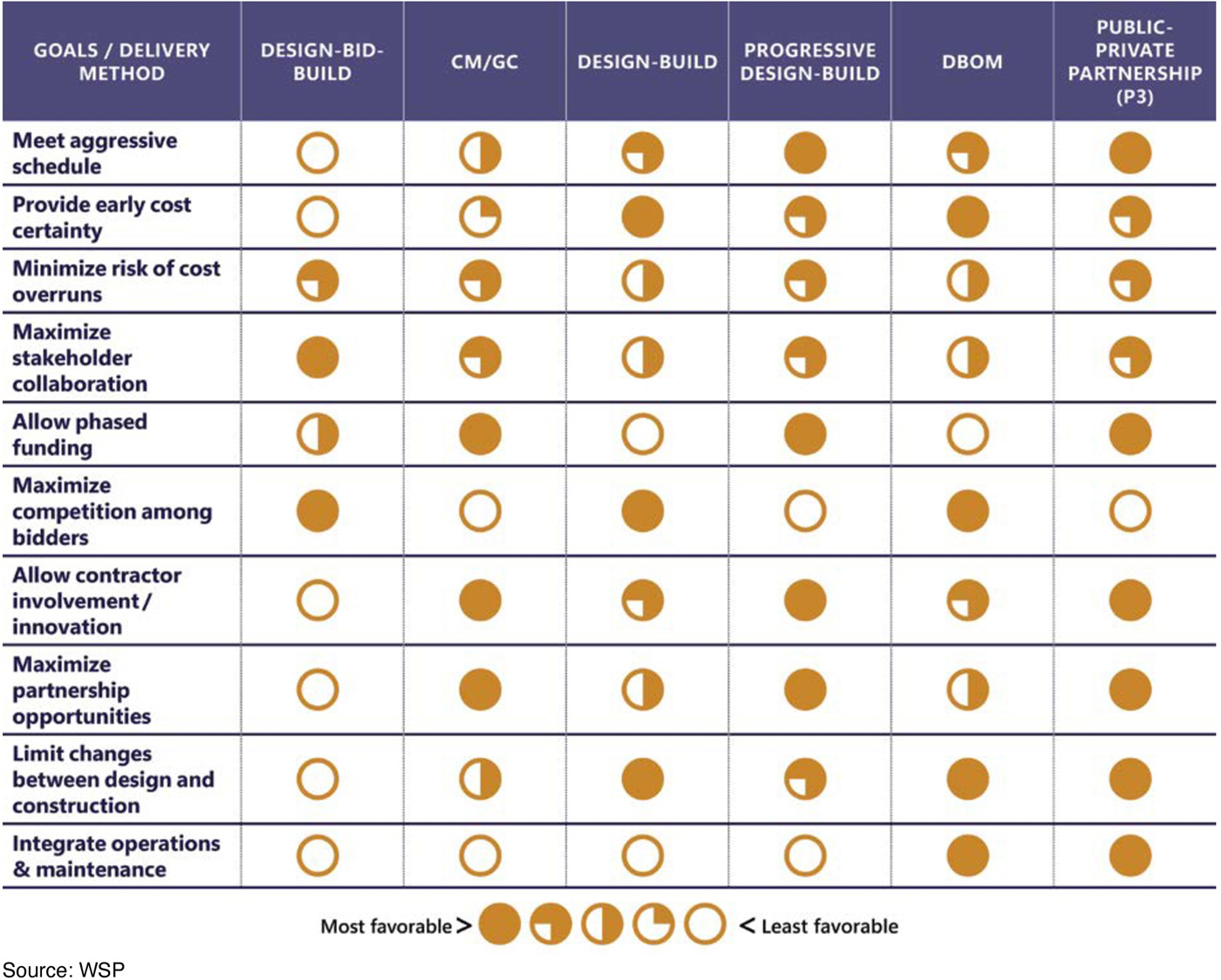

Evaluating Project Delivery Models

When evaluating project delivery options, project planners and owners should determine the legal authorities available, the goals for the procurement, and how each option meets the goals, which can include cost and schedule certainty, speed of delivery, integration of services, degree of risk transfer, and compatibility with existing services available to the owner. The evaluation process is typically both qualitative and quantitative.

Qualitative Comparison of Project Delivery

A qualitative comparison can identify necessary trade-offs to achieve stakeholder consensus. For more complex intermodal passenger facility projects, more than one delivery model may be appropriate for different project elements. For example, the redevelopment of Denver Union Station and the surrounding TOD project used a P3 for the station while a private real estate development team redeveloped the project around the station.

As an example, see Figure 10, which shows, by goal category, a hypothetical evaluation using the six models discussed in this chapter. In this example, the project goal was to quickly deliver a facility funded through facility revenue and downstream grants. The qualitative analysis indicated that P3 would be the most promising delivery model. P3 works in this instance because

of the project’s accelerated schedule; the ability to meet the funding profile; the integration of design, construction, and operations and maintenance; the ability to enhance innovation; and price and schedule certainty. A PDB delivery option also scores well but does not include operations and maintenance services.

Quantitative Analysis of Project Delivery Options

Following the qualitative evaluation, a quantitative analysis can be used for the most promising options to evaluate specific project risk assessments, update cost estimates, and compare schedules and conceptual financing plans for each delivery model. It is important that the analysis receive input from identified stakeholders and that they understand their roles, responsibilities, and how each delivery model will affect their workstreams and overall project governance. Table 9 shows the overall approach (both qualitative and quantitative analysis) to the selection of a delivery method.

Private Development Partnerships

Many intermodal passenger facilities include a private development component, either within the facility or adjacent to it. Assuming market conditions support a mix of new land uses to complement the facility, there are a variety of ways to integrate development. In most cases, this

Table 9. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of project delivery methods.

| Qualitative Analysis | Quantitative Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Options | Constraints | Feasibility study | Preferred option |

| Procurement method | Stakeholder objectives | Refinement of cost and revenue estimates | Variation over phases |

| Project scope | Market appetite | Risk analysis | Risk allocation |

| Phasing | Potential public funds | Financial structure | Governance |

| Legal | Value of options comparison | Legal changes | |

| Regulatory | Range of funding need | ||

Source: WSP

future development potential can and should be factored into the overall governance model and used as a source of potential funding. Ultimately, the most appropriate land development model will depend on who has property rights, including ownership and control of the developable area under consideration.

Joint Development

![]()

Depending on the development scenario and owner goals, developable land can be sold outright or developed through ground or air-rights leases. Detailed guidance on a range of development options is provided in TCRP Research Report 224: Guide to Joint Development for Public Transit Agencies (Raine et al. 2021). This report describes best practices for public transit agencies to optimize joint development opportunities and provides detailed guidance on each step of the process. The report defines joint development by its transactional relationship to the transit agency and its ability to generate lease or sale proceeds, cost avoidance arrangements, or other forms of financial return.

The scale and mix of potential uses will also influence the land development model and eventual selection of a single developer partner, multiple partners, or a master developer. In a scenario where there is a limited inventory of developable land, a single developer partner may be selected to deliver a specific use on a parcel or parcels. If the scale of developable land availability and development potential is larger, a master developer land development model may be more applicable. In this scenario, the master developer typically acquires the land and oversees the phased development of several parcels and uses. This model ensures that there is a holistic approach to the timing, scale, and mix of uses and that there is a cohesive planning framework around the intermodal passenger facility.

Provider Partnerships

Intermodal passenger facility owners may choose to form partnerships with modal providers and with others local entities. These include transportation management associations (TMAs), private mobility providers, social service agencies, and community-based organizations.

Transportation Management Associations

TMAs are nonprofit organizations made up of various public and private stakeholders collaborating to address specific transportation issues. TMAs often focus on alternatives to driving alone. While TMA funding traditionally derives from employed membership, federal grants in

partnership with local jurisdictions have become more common in recent years. [The Association for Commuter Transportation (https://www.actweb.org/) is a valuable resource for working with TMAs.]

Shared Mobility Providers

Cities across the United States (and the world) have responded to the growth in private shared mobility companies operating bikesharing, scooter sharing, ridehailing, and other services by requiring companies to obtain operating permits. Contracts with local governments typically include per-vehicle deployment fees and annual application renewal fees. In exchange, cities often limit the number of shared mobility providers allowed to enter the market, sometimes granting exclusive rights to operate within the market. Fees from these agreements can then be earmarked for infrastructure improvements, maintenance, or expansion.

![]()

TCRP Research Report 204: Partnerships Between Transit Agencies and Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) provides a review of partnerships between transit agencies and TNCs in the United States. (Curtis et al. 2019). The report also presents a partnership playbook that offers step-by-step guidance to transit practitioners interested in pursuing partnerships with TNCs. TCRP Research Report 221: Redesigning Transit Networks for the New Mobility Future (Byala et al. 2021) includes toolkits for leveraging partnerships with other entities and for working with the private sector.

Intermodal passenger facilities can also work with the local government to impose a small surcharge for each ridehailing/TNC trip. Trips to and from airports or major train stations could have additional surcharges for construction and maintenance of accommodating facilities.

Moreover, bikeshare programs such as Citi Bike in New York City and Divvy in Chicago have emerged through public–private partnerships. These partnerships unlock private investment through additional funding opportunities such as advertising revenue and corporate sponsorships. Also see the micromobility discussion in Chapter 6.