Intermodal Passenger Facility Planning and Decision-Making for Seamless Travel (2024)

Chapter: 4 A Typology of Intermodal Passenger Facilities

CHAPTER 4

A Typology of Intermodal Passenger Facilities

Introduction

As explained in Chapter 1, an intermodal passenger facility is a transportation hub served by at least two modes of travel with at least one travel mode being air, rail, bus, ferry, or passenger vessel. Intermodal passenger facilities are present throughout the United States in a variety of contexts and serve local, regional, interregional, and international travelers. Some are standalone facilities, meaning they provide access to another transportation mode and may be part of a network but are distinct from other passenger facilities in that network such as Amtrak stations, Greyhound bus stations, or a city’s main airport.

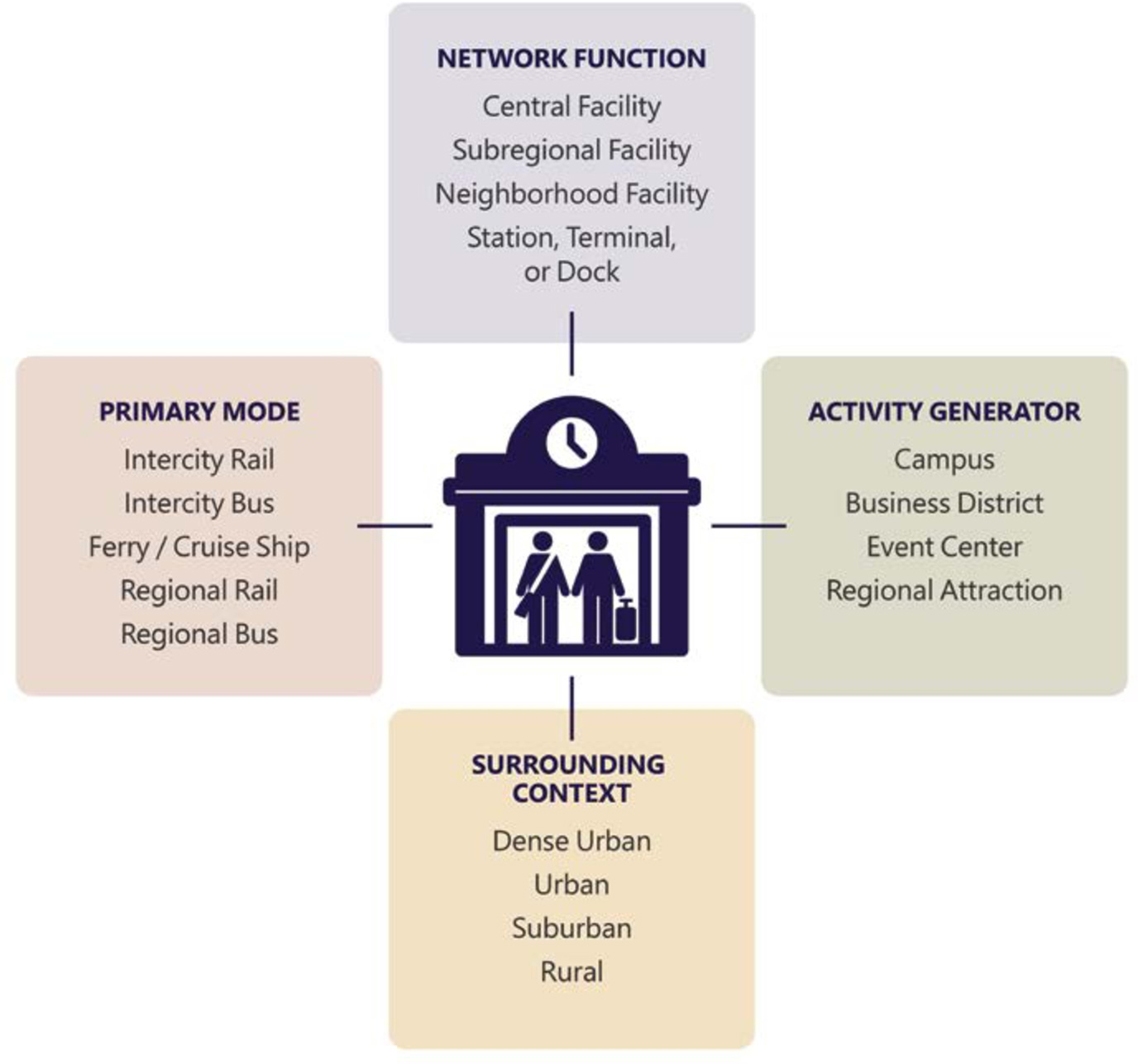

This chapter presents a typology of intermodal passenger facilities. The typology features four main components, as illustrated in Figure 4. For airports, the discussion covers intermodal components both within airports (airside) and outside airports (landside).

Categories of Intermodal Ground Passenger Facilities

The categories of intermodal ground transportation facilities are primary transportation mode or modes, network function, surrounding context, and activity generator or generators.

Primary Transportation Mode

The primary transportation mode represents the main mode or modes of travel the facility serves such as intercity rail, intercity bus, ferry service, cruise ship, regional rail (both commuter rail and subway), and regional bus (both commuter bus and other bus service).

Network Function

Intermodal passenger facilities with a primary function of facilitating travel by rail, bus, and ferry, and passenger vessel fall into one of four categories: central; subregional; neighborhood; or station, terminal, or dock, and range in level of complexity.

Central Facility

A central facility functions as a city’s or region’s main intermodal transportation hub and typically features multiple rail lines or bus routes. Many central facilities are in or near central business districts. Central facilities typically see the highest use within the overall network.

Subregional Facility

A subregional facility typically serves as a secondary transportation center that provides intermodal connections (e.g., subway and rail) and connections to the region’s central facility. Subregional facilities may also offer intercity rail or bus connections.

Neighborhood Facility

A neighborhood facility offers limited intermodal connections and provides local area access with links to a larger regional network.

Station, Terminal, or Dock

Some rail or bus stations are in more isolated locations and include intercity rail or bus stations, regional rail stations, or connections to passenger-vessel terminals/docks. These typically feature few if any secondary transit connections.

Surrounding Context

The amount of density and the extent of nearby or integrated development are key attributes of the surrounding environment. The typology uses urban, suburban, and rural contexts and considers four categories of population density: dense urban, urban, suburban, and rural.

Dense Urban

Intermodal ground passenger facilities located in dense urban areas, such as central business districts in large cities, typically function as central facilities and offer multiple modes. These facilities often include major developments that generate considerable activity.

Urban

In most cities, intermodal ground passenger facilities in urban areas include downtown transit centers and train stations. Such facilities may include a single public transportation mode such as a regional bus service. They may function either as central or subregional facilities.

Suburban

Facilities in suburban contexts can be situated within town centers or adjacent to regional roadway systems. Within the suburban context, parking supply can be a distinguishing characteristic. Functions include subregional, neighborhood, or station, terminal, or dock.

Rural

The rural context applies to individual facilities in areas with low density. These can be bus or rail stations or ferry docks.

Considering Pedestrian Circulation

Intermodal ground passenger facilities in lower-density areas may not support walking or bicycling. However, even when such facilities are auto-oriented, internal pedestrian circulation elements are vital and should be safe and fully accessible.

Activity Generator

The activity generator describes area development integrated with or adjacent to other intermodal ground passenger facilities. These developments can include medical and educational campuses, business districts, event centers, and major attractions. Business districts anchoring passenger facilities can range from traditional downtowns to office parks, and walking environments can vary accordingly. Event centers such as sports arenas have unique peaking characteristics, and major attractions may see seasonal variations in demand.

Intermodal Ground Passenger Facility Examples

Table 2 provides examples of intermodal ground passenger facilities that the research team interviewed representatives from, applies the typology categories, and shows the modes of transportation served. The table includes central, subregional, and neighborhood facilities in different contexts in terms of density and activity generated by surrounding developments.

Intermodal Components of Airports

The FAA categorizes U.S. airports according to their share of annual U.S. commercial enplanements, and as of 2022, the United States had 31 large-hub airports and 33 medium-hub airports that served at least 0.25% of total enplanements (Federal Aviation Administration 2023). Passenger travel at airports includes ground access (travel to and from airport), known as landside, and travel within terminals, known as airside. This report focuses on large-hub and medium-hub airports.

Travel to and From Airports

![]()

Ground access refers to travel to or from airports via external transportation systems and includes public and private transportation services and private automobiles. ACRP Report 4: Ground Access to Major Airports by Public Transportation, which provides resources to improve

Table 2. Typology examples for intermodal passenger facilities.

| Facility Name | Intercity Rail | Intercity Bus | Regional Rail | Regional Bus | Ferry | Function | Context | Activity Generator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlotte Transportation Center | √ | √ | Central | Urban | Business district, event center | |||

| Cincinnati Northside Transit Center | √ | Subregional | Suburban | None | ||||

| Denver Union Station | √ | √ | √ | √ | Central | Urban | Business district | |

| Fort Lauderdale Downtown Mobility Hub | √ | √ | Subregional | Urban |

Business district, campus |

|||

| Hoboken Terminal | √ | √ | √ | Subregional | Dense urban | Business district | ||

| Indianapolis Julia M. Carson Transit Center | √ | Central | Urban | Business district | ||||

| Los Angeles Union Station | √ | √ | √ | √ | Central | Urban | Business district | |

| North Nashville Transit Center | √ | Neighborhood | Urban | None | ||||

| Rio Metro Los Lunas Station | √ | Subregional | Rural | None | ||||

| San Francisco Ferry Terminal | √ | √ | √ | Central | Dense urban | Business district | ||

| San Francisco Transbay Terminal | √ | √ | Subregional | Dense urban | Business district | |||

| San Jose Diridon Station | √ | √ | √ | √ | Central | Urban | Business district | |

| Seattle Colman Dock | √ | √ | Subregional | Urban | Business district | |||

| Washington Union Station | √ | √ | √ | √ | Central | Dense urban | Business district, major attraction |

the quality of public transportation services at U.S. airports, defines public transportation access as via rail, bus, and shared-ride vans, but not single-party limousines, courtesy shuttles, or charter operations (Coogan et al. 2008).

While most of the primary and medium-hub airports in the United States offer some public transportation access as defined previously, connecting to such services varies. In some airports, individuals can walk to a nearby rail station, some require connections via bus or rail, and others offer curbside bus services. Public transportation use at most U.S. airports is relatively low, with only some seeing larger market shares. ACRP Report 4 analyzed 2005 origin–destination data to rank the volume of public transportation use at 27 U.S. airports, showing a range of 200,000 to 2,200,000 annual users. Just six of the 27 top airports had ground access market shares of at least 15% (San Francisco, New York JFK, Boston, Reagan National, Oakland, and New Orleans). Of these, San Francisco, New York JFK, Reagan National, and Oakland provide direct

rail connections. Boston provides shuttle service to nearby rail (Silver Line bus service between Logan Airport and South Station began in 2009), and New Orleans has no rail service.

Entering and Traveling Through Airports

The TSA manages airside access to U.S. airports. (It is worth noting that Amtrak also screens baggage on long-distance routes.) Individuals connecting from a domestic flight to another flight who remain in secured areas do not need additional screening. Except for international flights from airports with preclearance facilities (in 2024, preclearance was available in Ireland, Aruba, Bermuda, United Arab Emirates, Bahamas, and Canada), individuals arriving in the United States must go through immigration, and after retrieving checked baggage, must pass through customs. Individuals with checked bags connecting to another flight must recheck their bags and proceed through TSA screening.

Applying Station Typologies – Planning Examples

This section discusses examples applicable to all intermodal passenger facilities. The process of planning new intermodal passenger facilities or renovating existing facilities involves extensive coordination. For complex projects, the timeline can be lengthy, making it difficult to anticipate how travel will change. The following are examples of how some entities use typologies as part of the planning process.

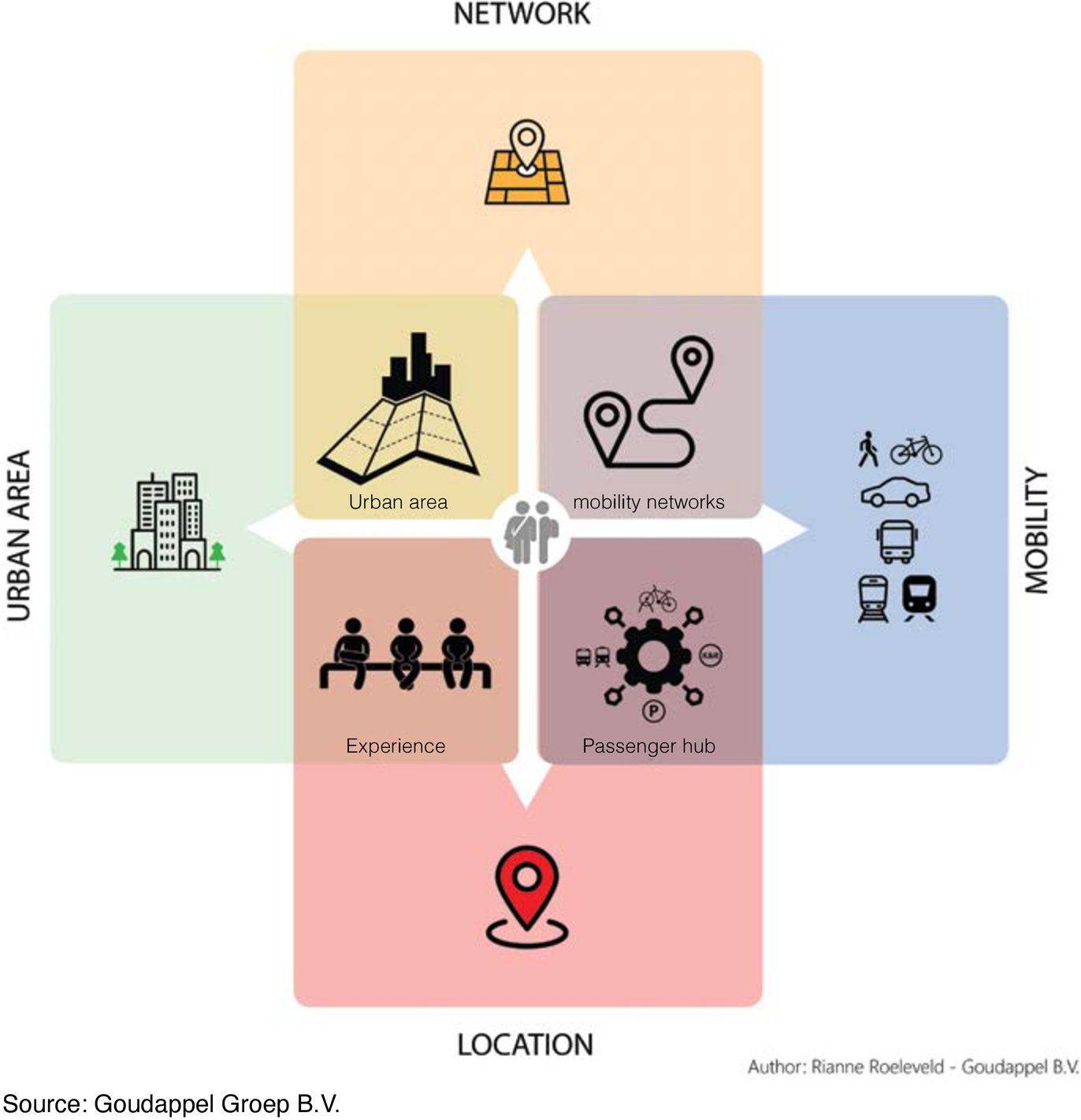

A Typology Framework for Station Area Planning in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, ProRail is responsible for maintaining and extending the Dutch National Railway network. The station area planning process for developing new or redeveloping existing stations considers the station’s urban context, available mobility options, and relationship to the larger rail transport network. Working with all stakeholders, the process developed by Goudappel Groep B.V. asks participants to characterize the current station area and to share their aspirations for its redevelopment. Figure 5 illustrates the relationship of the station’s function (network), urban areas (anchors), mobility (ground access), and location (context), which are key components used in the redevelopment of Leiden Station.

Because each station differs and each stakeholder community is unique, planners use this framework to establish collective understandings of current conditions and the desired future state. A key goal of planners is to build/rebuild intermodal passenger facilities that work well for all user groups (residents, visitors, and travelers—symbolized by the people at the center of the figure) who can enjoy the station as both a hub for mobility and for non-mobility activities. This might result in prioritizing walking and bicycling over driving as a station access mode, increasing security features, or improving ease of transferring between modes.

Using a Typology to Support Access Goals in Boston, Massachusetts

In 2020, the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) and the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) completed a station access study with three main goals. The first was to improve its customer focus by providing a safe, positive, and reliable customer experience. The second was to improve business performance by increasing transit ridership, increasing fiscal resiliency, and managing costs. The third goal was to improve social and environmental stewardship to reshape historical social inequities and combat climate change

(MassDOT and MBTA 2020a). The study included a typology for rapid transit service and for commuter rail that established station types based on context, magnitude of bus transfers, and mode of access (excluding buses), as presented in Table 3.

Applying Typology Principles to a Major Project: The Port Authority Bus Terminal Renovation

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) issued a draft environmental impact statement (DEIS) for its bus terminal replacement project in February 2024. This complex multiyear project will transform the user experience for customers, tenants, bus operators, and others and revitalize the surrounding areas of Manhattan. This project is in a dense urban business district and will replace the existing terminal. As part of area revitalization efforts and to help finance the cost, the project includes commercial development in new towers. At its core, however, the project will dramatically increase intermodal capacity. According to the DEIS, the project has the following goals:

- Improve bus operations through direct linkages to the Lincoln Tunnel and to bus storage and staging areas.

- Improve the customer experience in the terminal with amenities and through safety and security.

Table 3. MBTA station typology and mode shares.

| Primary Service | Station Type | Number of Stations | Magnitude of Bus Transfers | Mode Share (Except Bus Transfers) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walk or Bike | Drive Alone | Carpool | Dropped Off | ||||

| Rapid transit | Core | 68 | None to moderate | 95% | 1% | 0% | 4% |

| Neighborhood | 68 | None to moderate | 87% | 6% | 1% | 6% | |

| Regional | 26 | High | 83% | 7% | 1% | 9% | |

| Commuter rail | Town centers | 46 | None | 38% | 43% | 4% | 15% |

| Neighborhood | 29 | None to low | 70% | 21% | 2% | 7% | |

| Urban centers | 14 | Low | 31% | 44% | 3% | 22% | |

| Regional park-and-rides | 17 | None | 8% | 68% | 4% | 20% | |

| Local park-and-rides | 26 | None | 15% | 62% | 5% | 18% | |

Source: MassDOT and MBTA (2020a)

- Provide seamless passenger accessibility within the facility, strengthening transit connections and supporting bicycling and walking.

- Strive to achieve consistency with local and regional land use plans and initiatives through new civic spaces, as well as integration with the surrounding neighborhood and with West Midtown development projects.

- Optimize life-cycle costs through phased construction and other approaches.

- Reduce the impacts of bus services on the built and natural environment by reducing bus idling, unnecessary bus circulation, and local traffic impacts (Federal Transit Administration and Port Authority of NY & NJ 2024).