Social-Ecological Consequences of Future Wildfires and Smoke in the West: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 9 Stories from Impacted Communities

9

Stories from Impacted Communities

The panel showcasing and discussing stories drawn from wildfire-impacted communities was moderated by Frank Lake, committee member, and research ecologist for the U.S. Forest Service. The goal of the panel was to involve fire-affected communities and marginalized populations not only in creating an initial assessment of their shared needs but also in identifying areas where knowledge is lacking. The panelists were provided with the following guide questions: How did your community’s experiences contribute to planning for and reducing the impact of wildfires? What scientific research and evidence-based policy changes are needed to enhance community resilience and sustainability? How can scientific research and evidence-based policies be modified in order to promote strengthening community resilience and sustainability? The panel also aimed to gain an understanding of the factors that facilitated community-based recovery following specific wildfires, such as community engagement and insurance claims.

BEYOND THE VINEYARD: THE HIDDEN IMPACT OF WILDFIRES ON UNDOCUMENTED AND INDIGENOUS MIGRANT COMMUNITIES

Michael Méndez, Assistant Professor, University of California at Irvine

Shifting from the earlier discussions about socially vulnerable populations and communities, Méndez’s remarks focused on wildfire impacts on undocumented, Latino, and Indigenous migrant communities. His research delves into how views on human identity with respect to gender, class, race, indigeneity, and immigration status intersect with wildfire disasters.1

Méndez highlighted how during disasters these populations, despite facing significant challenges before a disaster strikes, often remain invisible in local and federal disaster planning. For instance, while wildfires have had a profound economic impact on California’s wine industry—including an estimated loss of $3.7 billion due to smoke taint,2 which affects grape quality, making wine both undrinkable and unsellable—he has observed that little attention is paid to the farm workers harvesting these grapes, and how smoke may be tainting their health. These

___________________

1 Méndez, M., Pastor, M., & Lesaca, A. C. (2024). Climate change, migration, and health disparities at and beyond the US-Mexico border. JAMA, 331(8), 696–697.

2 Adams, A. (2021, January 20). 2020 fires cause $3.7 billion in losses for wine industry. Wine Business. https://www.winebusiness.com/news/article/240575

people, working in hazardous conditions within mandatory evacuation zones, often lack adequate occupational health protections, hazard pay, or access to federal disaster relief funds.

Méndez stressed the importance of bringing these inequitable and hazardous conditions to everyone’s attention. He noted that with respect to social vulnerability and demographic data, the State of California may lack an appropriately comprehensive analysis of wildfires, particularly as regards their effects on undocumented, Latino, and Indigenous migrants. In California’s current climate crisis, it is critically important to understand how wildfires may exacerbate existing inequalities, stigmatization, and marginalization among these communities. By aiming to shed light on these issues, he is advocating for strategies to be used during extreme wildfire events to mitigate the harms encountered by undocumented, Latino, and Indigenous migrants.

He has observed that research focusing on the impact of wildfires on one of California’s most marginalized populations, undocumented Latino and Indigenous migrants, including migrants working as farmworkers, also holds global significance, since the wildfire issues in California are now affecting vulnerable populations worldwide. For instance, in 2020 smoke from multiple severe wildfires in the state reached as far as New York State and Western Europe. Due to the unique circumstances during disasters like wildfires, undocumented migrants, including Latino Indigenous populations and others, have faced heightened vulnerability. Given their pre-disaster marginalized status, they can encounter racial discrimination, economic hardships, fear of deportation, and language barriers—many having limited proficiency in English and Spanish—in their daily lives, even before a calamity occurs. Their conditions are distinct from the general concept of preexisting social vulnerability discussed by Susan Cutter (see Chapter 8). Méndez suggested that understanding how social vulnerability intersects with ongoing marginalization, discrimination, and societal stigmatization in these communities is crucial for effective disaster planning and response. The research done by Méndez has focused on not only addressing existing inequalities but also emphasizing how effective disaster risk reduction should begin before disasters occur by integrating migrants into social systems such as healthcare and unemployment.

Using a Co-productionist Research Framework

Méndez’s research on California wildfire impacts in three regions of California—Ventura, Santa Barbara, and Sonoma County,3 known for producing high-yield luxury crops like wine, strawberries, and other fruits and vegetables—employed a co-productionist framework. The research involved collaboration with migrant rights and environmental justice groups to establish appropriate research design, data collection, and analysis methods. Méndez noted that they presented findings to various policy audiences at local, state, federal, and international levels, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the United Nations Migration Agency, and the United Nations Human Settlements Program—as well as within California.

He observed that the co-productionist framework underscores how undocumented migrants—due to systemic racism, cultural norms surrounding U.S. citizenship, and their perceived “unworthiness” as disaster victims—could be overlooked in the public policy decision-making process. This research highlighted how political decisions could prioritize certain lives over others, underscoring that due to structural factors these populations, including undocumented migrants, are among the most severely affected by disasters like wildfires.

Méndez noted that climate change has extended and intensified wildfire seasons, with 17 of California’s 20 largest wildfires (by acreage) occurring since 2000. Sonoma County, a focal point of his research, sits within California’s renowned wine region and has endured several severe wildfire events. Some of these events, including the Tubbs Fire, ranked among the state’s top five most destructive and deadly, and others, including the Glass fire, ranked among the top 20. Since wildfires are projected to grow more frequent and intense, he remarked, it is crucial to understand why certain individuals and communities suffer disproportionately. Though there are many fire-prone areas in California populated by higher-income groups, these same areas also house hundreds of thousands of low-income residents who may lack the means to adequately prepare for or recover from wildfires. This

___________________

3 Méndez, M., Flores-Haro, G., & Zucker, L. (2020). The (in) visible victims of disaster: Understanding the vulnerability of undocumented Latino/a and Indigenous immigrants. Geoforum, 116, 50–62.

disparity is expected to worsen: the California Fourth Climate Assessment Report forecasts by 2100 a potential 77 percent increase in the state’s wildfire acreage burned.4

The Sonoma Fires

Even though Sonoma County has become a focal point for severe wildfires and environmental injustice-related issues within the state, Méndez pointed out that media coverage, government reports, and scholarly attention have predominantly highlighted the loss of coastal mansions and impacts on affluent homeowners and farmers. The wildfires in Sonoma County have not only devastated valuable properties and crops, he said, but also have posed serious health and livelihood risks to thousands of undocumented migrants. He highlighted the potential discrimination and hazardous working conditions these workers experienced during wildfires.

According to Méndez, an estimated 2.6 million undocumented migrants in California could face significant challenges exacerbated by wildfires. Méndez noted they might be overlooked in disaster planning and relief efforts. Sonoma County has a reported 27,000 undocumented people;5 however, he believes these official figures likely underestimate the accurate numbers of these people, due to their cultural and linguistic isolation, or fear of interacting with government officials. He said an estimated 12,000 Indigenous people from Mexico—populations that are neither Hispanic nor Latino, including Mixtec, Triqui, Maya, Chatino, and Zapotec peoples—live in Sonoma County. He described how many work in physically demanding roles crucial to the region’s agricultural productivity, yet they face numerous hardships including inadequate housing; limited access to healthcare and insurance; and language barriers—some speaking neither Spanish nor English, but only their native language.

Méndez said that during the Sonoma fires, migrant workers suffered disproportionately due to job losses, unsafe working conditions, a lack of evacuation information in their native languages, confusion over eligibility for disaster relief, lack of unemployment insurance, and poor housing and transportation. Despite California’s reputation for effective disaster response, these vulnerable populations experienced socioeconomic difficulties. The situation, compounded by the overlapping crises faced by marginalized communities in the state, highlights broader issues of social and economic inequality.

The Sonoma fires occurred amidst a heat wave, drought, and the COVID-19 pandemic, creating what Méndez referred to as a “syndemic”—which he described as a situation where, on top of other public health challenges, multiple disasters intersect and exacerbate existing health disparities. This compounded crisis underscored the need for tailored disaster planning addressing the unique vulnerabilities of undocumented migrants and those with seasonal work visas. These populations often hesitate to seek aid due to fears of deportation. Furthermore, language barriers, literacy, discrimination, and restrictions barring access to federal disaster assistance funds prevent them from accessing crucial support services during and after wildfires.

Since wildfire season aligns with harvest season each year, undocumented farm workers in Sonoma County can face significant health risks due to exposure to Particulate Matter (PM)2.56 from wildfire smoke, which contains toxic substances such as heavy metals. This type of particulate matter can be more harmful to human respiratory health compared to PM2.5 from other sources such as car exhaust.7 Workers may lack proper occupational health and safety standards, yet they play a crucial role—sometimes even entering mandatory evacuation zones without adequate protection—in protecting Sonoma’s wine grapes from smoke and ash during harvest season. Since 2015, due to wildfires, the annual mean PM2.5 particulate matter has increased in northern California, and this has been the primary cause of PM2.5 exceedances in the region.8 Furthermore, the detrimental health effects of wildfire

___________________

4 More information about the California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment is available at https://www.climateassessment.ca.gov/state/overview/

5 Migration Policy Institute. Profile of the unauthorized population: Sonoma County, CA. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/unauthorized-immigrant-population/county/6097

6 More information on particulate matter is available at https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/particulate-matter-pm-basics

7 Aguilera, R., Corringham, T., Gershunov, A., & Benmarhnia, T. (2021). Wildfire smoke impacts respiratory health more than fine particles from other sources: observational evidence from Southern California. Nature Communications, 12, Article 1493.

8 Liang, Y., Sengupta, D., Campmier, M. J., Lunderberg, D. M., Apte, J. S., & Goldstein, A. H. (2021). Wildfire smoke impacts on indoor air quality assessed using crowdsourced data in California. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(36), e2106478118.

smoke on farm workers may be greater even than previously thought, which Méndez said points to the urgent need for further research and policies aimed at protecting California’s most vulnerable and marginalized populations.9

Quotes from interviewees in Méndez’s research illustrate the severe impact of wildfires on Indigenous farm workers and landscapers in Sonoma County. One Indigenous farm worker, describing how smoke inhalation caused health issues for his entire family, said their “throats closed in from breathing too much smoke, and our kids couldn’t go to school.”10 Another landscaper described not only the tragic death of a colleague who had recently moved to the area, but also the loss of homes where they worked. He shared personal challenges, such as being a cancer survivor and “the only one who provides for the family.”11 An Indigenous farm worker described working for extended periods, sometimes weeks on end, in mandatory wildfire evacuation zones, leading to serious health effects such as black saliva resulting from prolonged exposure to smoke.12 Méndez believes that these stories underscore how pre-existing social inequalities and health disparities among farm workers are exacerbated during disasters such as wildfires—reinforcing the concept that people are experiencing a “syndemic.”

Other Disasters and Marginalized Groups

One implication of all this that Méndez highlighted was the urgent need to expand research to emphasize broader impacts on vulnerable populations like farm workers, thus going beyond focusing solely on property values, homeowners, and landowners.

To effectively reduce disaster risks, he suggested we must begin by socially integrating migrants into our broader population. He also stressed it is essential to recognize that undocumented migrants belong to some of the most stigmatized and marginalized communities—which is not an incidental occurrence, but a result of political decisions that withhold federal, state, and local resources from them. Understanding their plight in the broader context of disasters, Méndez said, could be essential for addressing these systemic inequalities. He emphasized that further research is needed to examine historical injustices faced by farm workers and undocumented migrants.13

Méndez compared the Pajaro flooding incident—which took place in northern California, near Santa Cruz, on March 12, 2023, highlighting the government’s longstanding neglect of levees that would eventually collapse—to the negligence seen in New Orleans’ Ninth Ward during Hurricane Katrina. Observing that more than 90 percent of those affected by the Pajaro flooding were farm workers, he said many of them were undocumented migrants, only a small fraction owning flood insurance.

The Pajaro flood took place on the 94th anniversary of California’s second most devastating disaster, the 1928 failure of St. Francis Dam,14 which impacted both Los Angeles and Ventura counties and disproportionately affected undocumented migrants with reports of both segregation in Red Cross shelters as well as challenges when it came to their receiving compensation for property losses from the Los Angeles City Department of Water and Power. Suggesting that these events point to the systemic issues faced by marginalized communities during disasters, Méndez highlighted the need for equitable policies and support mechanisms.

Méndez went on to mention research focusing on LGBTQ individuals, another highly marginalized and stigmatized group. Méndez, Leo Goldsmith, and Vanessa Raditz explored how LGBTQ communities experience significant social vulnerabilities during disasters. Their research underscores the fact that, in the context of disasters, LGBTQ people of color are disproportionately affected and displaced at twice the rate of non-LGBTQ individuals.15

___________________

9 Méndez, M., Flores-Haro, G., & Zucker, L. (2020). The (in) visible victims of disaster: Understanding the vulnerability of undocumented Latino/a and Indigenous immigrants. Geoforum, 116, 50–62.

10 Méndez, M. (2022). Behind the bougainvillea curtain: Wildfires and inequality. Issues in Science and Technology, 38(2), 84–90.

11 Méndez, M. (2022). Behind the bougainvillea curtain: Wildfires and inequality. Issues in Science and Technology, 38(2), 84–90.

12 Méndez, M. (2022). Behind the bougainvillea curtain: Wildfires and inequality. Issues in Science and Technology, 38(2), 84–90.

13 Mendéz, M., & Pastor, M. (2023, March 14). Opinion: What happened in Pajaro isn’t just a ‘natural’ disaster. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2023-03-14/flood-california-levee-atmospheric-river-monterey-county

14 Los Angeles Times. (1928, March 14). 200 dead, 300 missing, $7,000,000 loss in St. Francis Dam disaster. Los Angeles Times.

15 Goldsmith, L., Méndez, M., & Raditz, V. (2021). The need for equitable disaster response for LGBTQ+ communities. University of California.

RESILIENCE AND RENEWAL: INSIGHTS FROM THE SKEETCHESTN COMMUNITY IN SECWÉPEMC NATION

Marianne Ignace, Simon Fraser University, Linguistics and Indigenous Studies and Director,

First Nations Language Centre, and Ronald Ignace, a member of the

Secwépemc Nation in Interior British Columbia

Marianne and Ronald (Ron) Ignace spoke as community members living within the Skeetchestn Community in the Secwépemc Nation, located in the south-central interior of British Columbia. Spanning more than 70 years, Ron’s connection with the community is through birth and traditional training, and his wife’s is through marriage, kinship, and traditional adoption. Being authors and academics, each of whom has collaborated with communities throughout the Secwépemc Nation, they have written about Secwépmec Nation history, culture, and language, including in their discussions of traditional ecological knowledge and cultural fire.16 Experiencing two significant wildfires since 2017, they shared their various roles and experiences in those events.17

Marianne Ignace referenced historical accounts from ethnographer James Teit in the early 1900s, where elders explained that their ancestors recalled living in a time marked “by great winds, fires, and droughts”—events that resonate with the present challenges faced by their community.

Marianne Ignace provided details about the July 2017 wildfire in Elephant Hill, which started about 20 miles away in the neighboring community of Ashcroft. This wildfire engulfed approximately 1,900 square kilometers of forests, grasslands, homesteads, and houses on Indigenous reserves, impacting Secwépmec communities through property loss, destruction of forested areas, and the necessity of weeks-long evacuations.

Ron Ignace added that in 2017 the Indigenous community, during the Elephant Hill wildfire, found itself caught between provincial and federal jurisdictions. Despite having reached out to these authorities for assistance, Ron, who was the chief at the time, and his Council, faced significant challenges in getting them to respond effectively. Consequently, they decided to take matters into their own hands. Deciding to establish its own emergency response systems, including a command center, the community deployed not only its own experienced firefighters equipped with heavy-duty equipment, but also fire scouts who provided critical information about the fire’s behavior, weather, and environmental conditions.

He also described how he, as chief, and the Council welcomed onto their reserve a provincial fire-fighting crew of 300 after learning that their initial base had to relocate. They facilitated the crew’s establishment on their lands by initiating a ceremony, including the singing of honor and welcome songs, to show their gratitude toward them. Ron Ignace said he observed how the crew’s engagement in this ceremony transformed them from distinct and separate individuals into a unified team ready to collaborate closely with the community. They worked together to co-manage fire-fighting efforts, utilizing the ceremony, traditional knowledge, and community leadership to monitor and fight the fire, conduct backburns, and safeguard lives and property. Despite severe damage to their traditional lands, as well as a substantial estimated loss of cultural and natural resources amounting to a billion dollars, the community managed during the wildfire, through their collaborative efforts, to prevent injuries and property losses.

Marianne Ignace highlighted not only the importance of property loss but also the wider implications for Indigenous communities. She quoted Jenny Allen, resource manager for the neighboring community of St’uxwtéws (Bonaparte First Nation), who said

the government needs to understand the impact of this fire on our territories [...] that is our sustenance, that is our backyards, that is our livelihoods that we’ll never see again [...] our plants, and our foods, and our medicines, and our culture, and everything that is being completely destroyed by the fire [...] it is about our rights as Indigenous people living off the land ... And I don’t think that that is taken seriously enough (p. 42).18

___________________

16 Ignace, M., & Ignace, R. E. (2017). Secwépemc people, land, and laws: Yerí7 re stsq’ey’s-kucw (Vol. 90). McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.

17 Since July 2021, Ron Ignace has served as the National Commissioner of Indigenous Languages in Canada. However, Marianne Ignace said their presentation reflects Ron’s community voice and experiences predating his commissioner responsibilities.

18 Dickson-Hoyle, S., & John, C. (2021, November). Elephant Hill: Secwépemc leadership and lessons learned from the collective story of wildfire recovery. Secwepemcúl’ecw Restoration and Stewardship Society.

Marianne Ignace described a detailed report documenting the difficulties and challenges encountered during the 2017 Elephant Hill fire, as well as its subsequent restoration efforts and the broader political, economic, and social implications (p. 42).19 Emerging as a direct outcome of the Elephant Hill fire, the Secwepemcúl’ecw Restoration and Stewardship Society (SRSS)20 adopted as its primary focus land restoration projects guided by the belief that community members are Yecwemin’men—caretakers and stewards of the land.

Ron Ignace explained: “In our language, the term x7ensq’t tells us that if you don’t respect the land, the land will turn on you. The flip side to this, or corollary, is if you care for the land and respect it, the land in turn will care for you.”

Summarizing the restoration efforts after the fire, Marianne Ignace said 192,000 hectares were burned, necessitating the rehabilitation of 582 kilometers of fireguards and the reconstruction of 360 kilometers of fences.21 Additionally, 1.03 million square meters of timber were harvested and salvaged, with 35.3 million trees planted. Moreover, 218 archaeological sites were newly recorded due to the burnt and bare understory, revealing sites that were previously hidden.

Ron Ignace conducted research, and he heard from others that after forest fires, mushroom pickers often invaded territories, leaving human waste and garbage strewn across the forests. This prompted the establishment of the SRSS with the aim being to unite communities and enforce their traditional laws. Implementing a monitoring system to oversee mushroom buyers and pickers, SRSS instituted a licensing system under their sovereignty laws. Demonstrating their role as caretakers of the land, they not only successfully managed to prevent break-ins, he said, but also cleaned up thousands of liters of human waste and 15,000 pounds of garbage from the mountains.

Another outcome that Marianne Ignace referenced was the creation of the Declaration on the understory within the forests of Secwepemcúl’ecw—an initiative that was critical for the continuing ecological health of the forests in Secwépemc Territory and the well-being of the Secwépmec people. At the outset, instead of relying on English-speaking resource managers, they engaged their elders, who speak the language, to articulate their traditional knowledge of land stewardship. They shared insights on how to care for the land, the impacts of wildfires, and the interconnectedness of land, fire, and water management. Rooted in their wisdom, this process led to the establishment of the Declaration on the understory within the forests of Secwepemcúl’ecw.22

Following the 2017 fire, the community and neighboring communities underwent extensive training in firefighting, emergency response, community protection, and prescribed fire use. Despite these efforts, the severity of the 2021 Sparks Lake fire led to a six-week evacuation of Skeetchestn. However, employing the same emergency response tactics as in 2017 prevented significant damage. Additionally, Marianne described how a second fire, the Tremont Creek Fire, which occurred in the south, caused similar devastation, impacting a total of 1,540 square kilometers, many which were previously burned by wildfires. In mid-July 2021, the wildfire approached within approximately 250 yards of Skeetchestn, endangering the school and other parts of the community. In the end, a community-led backburn saved them from potential destruction.

Ron Ignace described how a trained member of the community, guided by teachings from elders, proposed a backburning strategy to the provincial fire-fighting crew working with them; they were able to successfully convince the crew that this approach would protect the school. Ron Ignace observed that through this collaborative effort, the backburning operation saved the school building from being consumed by the fire.

Marianne Ignace elaborated that the fire severely impacted significant spiritual sites such as the Pelúkes (Dead-man Falls) waterfall, which has held deep cultural and spiritual significance within the community for centuries. The elders, highlighting its historical significance, refer to this place as Q’wempúl’ecw. The land, she noted, has unfortunately faced depletion from fires, droughts, and other environmental factors.

One crucial aspect of resilience-building, Marianna Ignace said, involves restoring cultural fire practices.

___________________

19 Dickson-Hoyle, S., & John, C. (2021, November). Elephant Hill: Secwépemc leadership and lessons learned from the collective story of wildfire recovery. Secwepemcúl’ecw Restoration and Stewardship Society.

20 More about the Secwepemcúl’ecw Restoration and Stewardship Society is available at https://srssociety.com/

21 Dickson-Hoyle, S., & John, C. (2021, November). Elephant Hill: Secwépemc leadership and lessons learned from the collective story of wildfire recovery. Secwepemcúl’ecw Restoration and Stewardship Society.

22 The Declaration on the understory within the forests of Secwepemcúl’ecw, and more information about it, are available at https://watershedsentinel.ca/articles/values-and-morels/

Living on an approximately 20,000-hectare reservation grants them the ability to conduct controlled burns on forest edges and grasslands, which foster the regrowth of traditional plants and cultural keystone species such as yellow bells (Tecoma stans L. Juss ex. Kunth) and biscuitroot (Lomatium triternatum J. M. Coult. & Rose). Despite the devastation caused by the 2017 Elephant Hill fire, she noted that for her it was a heartening sight in July 2023 to see cultural keystone species like soap berries beginning to return in the cooler, burn-affected areas. Marianne described how this resurgence is seen as a symbol of hope for their community’s future. Ron Ignace observed that after the controlled burns, yellow bells and biscuitroot plants, which had not grown in that area for a century, were seen successfully regenerating from the soil. Also, the controlled burns not only restored native grasses but also eliminated invasive species.

REFLECTIONS ON LOSS AND RENEWAL: COMMUNITY STORIES FROM THE CZU LIGHTNING COMPLEX FIRE

Irene Lusztig, Indigenous Leadership Initiative

Lusztig was part of the community affected by the 2020 CZU Lightning Complex Fire, which destroyed 900 homes. This experience made her think deeply about the trauma she shared with her neighbors. She reflected on Susan Cutter’s description (see Chapter 8) of a feeling somewhere between topophilia and solastalgia, capturing as Cutter did the tension between love for a beautiful place and the sorrow for its destruction. Lusztig described how during her evacuation, and afterward, she spent a lot of time inventorying her belongings, a task many people realized only belatedly they should do. Making notes on pictures in order to remind herself of what she had, she documented all the items she evacuated from the fire—in case more might be lost.

After returning home from the five-week evacuation, she started reflecting on how to measure loss, especially for items with immense sentimental, but no financial, value. Lusztig focused on objects like a cup from her great-grandmother, a 1980s cassette tape labeled “memory tape,” her grandfather’s camera, and postcards from her parents. This led her to consider the difference between insurance claims, which require a dollar price for each object, and the sentimental value that many items hold. The insurance inventory process is often intense, laborious, and re-traumatizing for those who have experienced such devastating fires. Lusztig highlighted the complex emotional sense of loss that people feel when in a fire their homes and all their belongings—many of which have huge sentimental but zero commercial value—are taken from them.

After her evacuation, Lusztig noticed a surge in community support, with people offering a variety of services to help those who had lost their homes. Reflecting on how she could contribute, she decided to use her skills to create a space for people to share their stories and feelings. She reached out to her community through a Survivor Rebuilding Facebook group, inviting anyone affected by the fire to talk with her. Her aim was to listen to and document their experiences, focusing in this way on the prolonged recovery process. While there is often a burst of media attention and immediate aid right after a disaster, these responses and resources tend to dwindle after a few weeks or months, leaving for the affected individuals a long, ongoing journey of recovery.

Now, four years after the fire, Lusztig noted that only 104 out of 900 homes had been rebuilt. People had exhausted their living-expense coverage funds from insurance and may feel abandoned by the services and structures that initially supported them. Extending her post-fire early contact with people, her goal was to continue checking in with community members over time. For the next nine months, she invited people to share their memories, talk about their homes, and discuss meaningful objects they had salvaged. Some were initially too traumatized to participate but, over time, they eventually opened up. She also explored the emotional impact of the contents inventory process, aiming to create a more nuanced understanding of loss beyond just the listing of items. Her project aimed to go beyond focusing on a spreadsheet of items, by collectively reimagining an emotional contents inventory that could address the complex losses people experienced.

Lusztig shared a photo of Gemma, showing a sculpture on her phone that, although burned, survived the fire. Gemma is a fifth-generation family member from the mountains who lost everything and lacked insurance, preventing her from rebuilding. Another neighbor, Andy, shared a sign from his property, standing in front of his burned land—the sign having survived the fire. Kirsten, who lives near Lusztig’s house, brought a door hinge she

found and told how she had gone on an obsessive search for its matching hinge so the original hinge could feel whole again; unfortunately, she ended up finding only the one. Jason, Shannon, and their child Emmett shared a cup they found under their collapsed home’s debris; written on it were the words “I love dad.” Lusztig observed that these items reflect the deep, personal losses experienced by members of the community.

Lusztig stated that the rebuilding process has been incredibly challenging due to obstacles such as the following: difficulties associated with meeting the building permit requirements; the need for sprinkler systems with water pressure higher than what the county supplies; and having to rebuild wider roads for fire trucks—all of which are financially out-of-reach obligations for individual people who are trying to rebuild. Many people have also faced insurance cancellations, adding to their problems. In closing, Lusztig mentioned that although the community still experiences significant trauma and grief, there are hopeful signs of renewal—for example, the new growth in the forest.

INDIGENOUS LEADERSHIP AND RESILIENCE IN CANADA

Amy Cardinal Christianson, Policy Advisor, Indigenous Leadership Initiative

The Indigenous Leadership Initiative23 is a Canadian national Indigenous organization focusing on Indigenous nationhood and leadership through conservation. Currently leading a fire stewardship program, Amy Cardinal Christianson shared statistics, from 1980 to 2021, on wildfire evacuations in Canada.24 Due to the limited time and the extensive fact-checking required (given its sheer scale) she did not include in her remarks the extreme 2023 wildfire season.

The data points Christianson presented indicate an increasing trend in the annual number of evacuation events. From 1980 to 2021, the median number of events per year was 22, with a minimum of one and a maximum of 217 in 2021. This trend was exceeded in 2023. While there are limitations, such as potential over-reporting, the overall trend indicates more events and more frequent evacuations. On the evacuees’ side, 2016 saw a notable spike due to the Fort McMurray evacuation. In 2023, more than 200,000 evacuees were recorded, suggesting a growing impact on the number of evacuations. Analyzing evacuee numbers provides a way to measure social impacts, complementing data on the area burned.

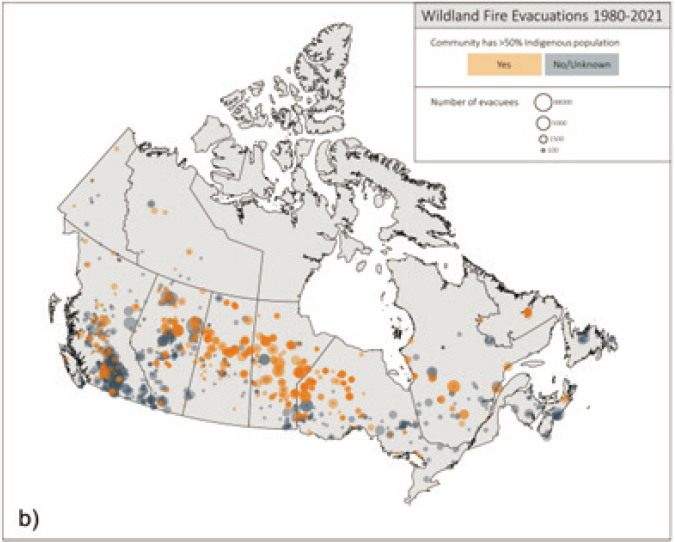

Christianson’s work focuses on Canadian Indigenous peoples, specifically the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit groups. Figure 9-1 illustrates the evacuations across Canada over 42 years, with the size of the dot indicating the number of evacuees. The orange dots, notably, represent evacuations of Indigenous communities. Although Indigenous people make up approximately 5 percent of Canada’s population, they account for over 42 percent of evacuation events in Canada.

Christianson explained that, additionally, most Indigenous people do not have insurance due to the nature of home ownership on reserves and other factors. People not having insurance may exacerbate the impact of evacuations because there are no backup systems in place. Christianson has observed that Indigenous communities also tend to have much lower income levels than the general Canadian population, making recovery even more challenging.

During the relevant 42 years, 16 Indigenous communities in Canada have been evacuated five or more times.25 All but one, West Kelowna, BC, are First Nation communities. Christianson emphasized that this highlights the disproportionate impact of fire events on Indigenous communities. For example, Red Sucker Lake in Manitoba and Summer Beaver have both been evacuated, in each case seven times, as have Deer Lake in Ontario and St. Theresa Point First Nation in Manitoba. While the populations in these areas are smaller than in cities such as Fort McMurray, they face repeated evacuations, which she said points to the significant impact of wildfires on Indigenous nations.

___________________

23 More information about the Indigenous Leadership Initiative is available at https://www.ilinationhood.ca/

24 Christianson, A. C., Johnston, L. M., Oliver, J. A., Watson, D., Young, D., MacDonald, H., Little, J., Macnab, B., & Gonzalez, B. N. (2024). Wildland fire evacuations in Canada from 1980 to 2021. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 33, WF23097.

25 Christianson, A. C., Johnston, L. M., Oliver, J. A., Watson, D., Young, D., MacDonald, H., Little, J., Macnab, B., & Gonzalez, B. N. (2024). Wildland fire evacuations in Canada from 1980 to 2021. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 33, WF23097.

NOTE: Spatial location of wildfire evacuation events (points) and number of evacuees (point size) (1980–2021) for evacuations recorded in the evacuation database. Color-coded by communities that have >50% Indigenous population (shown in orange) or communities that have either ≤50% Indigenous population or an unknown level of Indigenous population (shown in grey); darker shade indicates where there has been a higher density of evacuations. Workshop presentation by Amy Christianson June 14, 2024 (slide 3).

SOURCE: Christianson, A. C., Johnston, L. M., Oliver, J. A., Watson, D., Young, D., MacDonald, H., Little, J., Macnab, B., & Gonzalez, B. N. (2024). Wildland fire evacuations in Canada from 1980 to 2021. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 33, WF23097.

Christianson explained that in Canada, First Nation Reserves are overwhelmingly the most frequently evacuated communities. Many Indigenous communities are evacuated even when there is no direct fire risk, due to poor air quality from smoke. She has also observed that many First Nation communities require air evacuations, necessitating Department of Defense assistance with large aircraft due to a lack of road access in the summer. These evacuations can take three to seven days, and they typically displace people for a month or more, she said, resulting in significant impacts.

In 42 years, the cost of wildfire evacuations in Canada, excluding structural loss or insurance values, has reached approximately $3.7 CAD billion. When considering productivity losses due to displaced individuals unable to work, this figure is estimated to be at $4.6 CAD billion.26 In Canada, the approach to wildfire risk often involves mandatory evacuations—rather than allowing residents to stay and defend their own properties, as seen in some other countries, such as Australia. This forced evacuation approach carries risks, including fatalities.

The Indigenous Leadership Initiative is focused on rethinking fire management in Canada. Christianson suggested moving away from the current fire suppression model—which is costly and ineffective—and moving toward an approach based on four key directions, which would strengthen nationhood through fire kinship:

- Capacity building: Empowering Indigenous nations, drawing upon an Indigenous-led perspective, to manage, respond to, and recover from fires;

- Knowledge sovereignty: Ensuring that Indigenous communities control their traditional knowledge about fire and land stewardship, and in so doing prevent its appropriation;

___________________

26 Christianson, A. C., Johnston, L. M., Oliver, J. A., Watson, D., Young, D., MacDonald, H., Little, J., Macnab, B., & Gonzalez, B. N. (2024). Wildland fire evacuations in Canada from 1980 to 2021. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 33, WF23097.

- Fire governance: Establishing governance structures where Indigenous nations make decisions about their land; and

- Territories of abundance: Enabling Indigenous nations to maintain their cultural practices through effective fire management.

Christianson described several pilot projects, including fire guardian workshops, intended to define and fund year-round fire guardian roles through the development of an Indigenous Fire Stewardship State of Play for Canada.27 Doing this would also include analyzing how funding is distributed to Indigenous communities—versus distribution to other agencies. Other projects include the Riding Mountain Alliance, the Innu Nation wildland firefighter training, and the formation of a national advocacy group called the Thunderbird Collective.

DISCUSSION

Decolonizing Fire Management: Restoring Indigenous Knowledge and Leadership

Lake asked Christianson about the importance of decolonizing, fire management, and collaborating with colonial institutions. Responding, Christianson emphasized the need to recognize that many of the current wildfire effects—including fire exclusion, suppression policies, and the removal of Indigenous fire stewardship—are a result of colonization. To understand present risk levels and plan for the future, she stressed the importance of acknowledging these factors.

Christianson expanded on this by pointing out that while media and government often attribute the increasing evacuations in Canada to climate change, Indigenous nations counter by pointing out that their historical governance structures and fire knowledge were forcibly taken from them through colonization, residential schools, the Indian Act,28 and the Sixties Scoop.29 Christianson described how these events led to the exclusion of fire from forests that require it for health, exacerbating current problems. Indigenous communities, most of them affected by fires, advocate for their being allowed to lead fire-related decision-making. It may be that current government agencies and university-trained experts dominate fire management, Christianson argued, excluding those with practical, traditional knowledge of the land.

Preparedness in Forest Communities: Integrating Indigenous Teachings

Based on a First Nations and community perspective, Lake observed how there is a large amount of forest fuel immediately next to the housing areas. Based on the Indigenous teachings Lake has learned, he emphasized the importance of keeping areas open and clean in order to create defensible space, a cultural cornerstone of living with fire. He wondered how much of this is an accepted risk for those who know there could be a fire in the community—or recognize the need to be fire-prepared? He inquired about what else a community might learn from Indigenous teachings.

Lusztig suggested it might be a combination of factors. From her conversations with community members, she noted that many people are very attached to living among the trees and having them on their property. One neighbor mentioned how painful it was to have trees removed. Lusztig pointed out that while there are neoliberal, individualized mandates for making properties defensible, it may not be affordable or feasible for everyone to manage their property in this way. She observed that there are not adequate programs, infrastructure, or funding to

___________________

27 More information about Indigenous fire stewardship in Canada is available at Hoffman, K. M., Christianson, A. C., Dickson-Hoyle, S., Copes-Gerbitz, K., Nikolakis, W., Diabo, D. A., McLeod, R., Michell, H. J., Al Mamun, A., Zahara, A., Mauro, N., Gilchrist, J., Ross, R. M., & Daniels, L. D. (2022). The right to burn: Barriers and opportunities for Indigenous-led fire stewardship in Canada. FACETS, 7(1), 464–481.

28 More information about the Indian Act is available at https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-5/

29 More information about the Sixties Scoop is available at https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-northern-affairs/news/2017/10/sixties_scoop_agreementinprinciple.html

make it possible for everyone in the community to create defensible space. Some programs exist, but in the effort to effectively manage people’s properties they do not sufficiently support the entire community.

Bridging Indigenous Knowledge and Resilience: Innovations in Cross-Cultural Collaboration

Lake returned to Ron Ignace’s concept of “two-leg walking” and connected it with Méndez’s perspectives on not only the importance of an Indigenous workforce but also the vulnerabilities and unique contributions of Indigenous communities.

Marianne Ignace elaborated that the concept “walking on two legs,” introduced by Ron a couple of years ago, is action-oriented; in other words, it is aimed at advancing initiatives within reservations, akin to maintaining cultural sovereignty and reclaiming lands post-colonization. The idea is to foster dialogue between Indigenous and Western knowledge, emphasizing Indigenous knowledge as not only central to community needs but also providing a moral compass for scientific practices like those of natural scientists and ecologists. The aim is to meet Indigenous needs, Ron Ignace stressed; the approach, he said, involves “adapting and not adopting the Western sciences.”

Based on his observations in northern California, Lake noted that discussions on workforce capacity are heavily influenced by Indigenous knowledge. Many contractors in Indigenous territories, he pointed out, are not only Latino but also Indigenous people from Mexico. As part of a broader strategy for Indigenous justice, he questioned how best to support Indigenous workers who are engaged in both fuel reduction and efforts to enhance wildfire resilience. Lake also raised the issue of fostering greater equity among Indigenous communities across Mexico, the United States, and Canada.

Méndez said he values his collaboration, in the disaster studies field, with colleagues who are engaged in global Indigenous studies. He has observed they recognize that Indigenous migrants from North America and the broader Americas offer an important perspective on climate-induced disasters. Working with labor rights and migrant rights groups in northern California, they share the common goal, he pointed out, of addressing extractive and inequitable practices in climate resilience work.

Their initiatives include programs designed to enhance community resilience by adapting local ecologies, such as clearing brush and improving infrastructure for homeowners and properties. These efforts aim to provide fair wages and support for the Indigenous migrants—who are predominantly from southern Mexico—collaborating with California Native American tribes. This cross-cultural exchange, which he said is relevant across the United States and Canada, not only fosters dialogue but also the sharing of Indigenous practices related to wildfires.

This pilot program—which Méndez noted reflects a step forward in their collective efforts in the way that it facilitates meaningful cross-cultural and linguistic exchanges between California Native American tribes and Indigenous Mexicans from southern regions—represents an empowering and innovative approach.

Perspectives on Fire Resilience and Cultural Sustainability: Insights from Indigenous Communities

Regarding what was presented, Lake asked the panelists about the similarities and differences they observed. From Christianson’s perspective, the common thread is that the struggle continues in many ways. In discussions about fire, there is often a focus on homeowners and insurance. However, numerous vulnerable communities are not concerned with assets or insurance, she said, but are more focused on survival. This emphasis on survival, she pointed out, extends to their territories and the longevity of their culture. The similarity she observes has to do with the need to shift more attention to how the struggle is often a matter of life and death in these communities. Christianson pointed out that for Indigenous people, it is not all just about structures, but how high-intensity fires can get in the way of cultural practices for generations to come, thus deeply impacting in this way the essence of the culture.

Marianne Ignace shared that upon returning from evacuation and witnessing the devastation in their homeland, community members and elders expressed a profound concern, emphasizing in this concern the need to protect and restore the land for future generations. Reflecting on a recent climate change panel she attended, she noted a critical need to reevaluate how society attributes responsibility to climate change. She highlighted how irresponsible

land behavior could lead to consequences from both “the land and the sky,” which holds deep cultural significance. She stressed the importance of contemplating the profound implications of these concepts.

Ron Ignace added that another similarity in the workshop discussions was the evident post-colonial lack of respect for Indigenous community members’ knowledge gained from living on the land, their experience managing resources, as well as the way they care for one another. Government actions, he said, sometimes demonstrate this disrespect. For instance, he recounted how on one occasion the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) came to send news to non-Native people near their reserve, but they initially had no plan to notify the Indigenous people. When the RCMP attempted to do their job, they got lost in the mountains and had to return to seek assistance from the Indigenous people that they had disregarded.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Jonathan Fink, Committee Chair and Professor at Portland State University

Méndez highlighted the disproportionate vulnerability of migrant workers to multiple hazards. Fink noted that Méndez emphasized the need to better integrate and understand these individuals before disasters hit, considering their language, culture, and socioeconomic situations.

Marianne and Ron Ignace described how they developed their own firefighting and recovery capabilities due to two devastating fires in 2017 and 2021, and improved coordination with government agencies, which had previously provided inadequate coverage.

Lusztig provided context for her interviews with fellow victims of fires in Santa Cruz, California, which were captured in her film Contents Inventory. She noted that recovery can be very long.

Christianson discussed her work with the Indigenous Leadership Initiative on fire stewardship. She talked about the increasing number of evacuations and evacuees from Canada’s wildfires from 1980 to 2021. She highlighted the need to change the fire models for Canada.