Social-Ecological Consequences of Future Wildfires and Smoke in the West: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 5 Real-World Perspectives on Wildfire: Analyzing Case Studies from the Fort McMurray, Woolsey, and Maui Case Studies

5

Real-World Perspectives on Wildfire: Analyzing Case Studies from the Fort McMurray, Woolsey, and Maui Case Studies

Specific case studies were chosen for their location and impact. These wildfire-related case studies bring together and ground in real-world experience the workshop speakers’ varied perspectives. The session moderator, Oceana Puananilei Francis, committee member and professor at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, explained that four questions had been developed to guide the discussion: What was unique or specific in each particular case study? What were the unique or unexpected problems during and after the specific fire event? What lessons were learned that can be used to guide preparations for future fires? What are the commonalities among these three cases? These questions will help frame the panelists discussions.

FORT MCMURRAY WILDFIRE, ALBERTA, CANADA

Tara McGee, Professor at the University of Alberta

The Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo (RMWB), located in northeastern Alberta, covers nearly 70,000 square kilometers, or 10 percent of the province. This area was originally home to Indigenous peoples, and currently includes six First Nations and six Métis communities. Beginning in the late 1960s, RMWB also became known for its large-scale oil sands development, related oil industry activity, and service industry which have attracted workers from across Canada and internationally. This industrial development has led to rapid population growth, from just over 65,000 people in 2011 to over 71,000 in 2016, a 9 percent increase.1 With the majority of RMWB’s population residing in urban Fort McMurray, for many neighborhoods Highway 63 is the only road leading in and out of the city.

Beginning on Sunday, May 1, 2016, due to extremely hot and dry conditions, the Horse River Fire quickly grew. At 8:00 p.m. that evening, the RMWB warned residents in Fort McMurray’s Centennial Trailer Park neighborhood to evacuate, while the Beacon Hill and Gregoire neighborhoods were put on evacuation alert. A state of local emergency was declared at 10:00 p.m. for Centennial Trailer Park, Gregoire, and Prairie Creek. Although the warnings for Gregoire and Prairie Creek were rescinded the next morning, the fire continued to grow and was almost one kilometer from Highway 63. The fire expanded west overnight, moving away from Fort McMurray.

___________________

1 Statistics Canada. (2017). Wood Buffalo, SM [Census subdivision], Alberta and Saskatchewan [Province] (table). Census Profile, 2016 Census (No. 98-316-X2016001). Statistics Canada Catalogue. Ottawa. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

On the morning of Tuesday, May 3, the sky was clear and sunny, with no smoke or flames being visible from the city—but at 11:00 a.m. the fire chief warned that winds could shift.2

By noon on May 3, the fire had jumped the Athabasca River, approximately one kilometer away, and was heading toward the city. Later that day the fire entered Fort McMurray. The first impact was in Beacon Hill, Abasand, and the MacKenzie Industrial Park. Ultimately, a mandatory evacuation for all of Fort McMurray was issued by the RMWB at 4:20 p.m. Entering the subdivisions of Thickwood and Waterways later in the evening, the wildfire ultimately destroyed 2,400 homes and forced more than 88,000 people to evacuate.3

Fort McMurray is located in a fire-prone boreal forest, and between 1990 and 2012 five previous large wildfires had taken place nearby (within 20 km of the area).4 In 2016, Fort McMurray experienced a dry and mild winter, followed by an unusually hot and dry spring. Conducting an online survey of evacuees, McGee examined not only how prepared the residents of Fort McMurray had been before they evacuated, but also their experiences during the wildfire, when leaving their homes and communities, and during the time they spent staying in safe places.5 Reflecting back to a few days before the evacuation, 447 participants were asked, with regard to preparedness, to rate how they had perceived the threat of wildfire: 44.8 percent of respondents had perceived the wildfire threat to be low or very low; 28.7 percent had viewed it to be moderate; and only 25.5 percent had viewed it to be high or very high. Many people were not aware of the threat, McGee pointed out, despite the environmental cues. This perception of the threat being so low was, she went on to suggest, likely influenced by social cues. One survey respondent who had to evacuate noted that a fire captain had reassured people the previous day that the fire “was far away and not to worry.” McGee drew attention to how trusted officials provided information downplaying the risk.

Many residents, not having received an official evacuation order, had decided to leave either after seeing houses burning or after being advised to do so by friends, family, or neighbors. “The evacuation was very chaotic,” one respondent commented. “We were not told to leave Beacon Hill until houses were already on fire.”6 When the mandatory evacuation was issued, residents living south of the Athabasca River were directed to head south on Highway 63. Those north of the river, due to traffic tie-ups going south, were instructed to go north on Highway 63 toward Fort McKay First Nation.

An estimated 15,000 to 20,000 evacuees drove north.7 During the initial evacuations, many people stayed in work camps at the oil sands and Fort McKay First Nation. Later that night, at 10:00 p.m., a mandatory evacuation was also ordered for Anzac, Gregoire Lake Estates, and Fort McMurray First Nation, all located south of the city.

A few days after May 3, with the fire continuing and heading north at that time, supplies in the work camps began to run out. Evacuees who had headed north and were then staying in the above-mentioned camps either were flown to Calgary or Edmonton or else proceeded to drive south on Highway 63, passing through Fort McMurray before relocating. For residents leaving their neighborhoods, including those on Highway 63 heading north or south, traffic delays were common. Having little time to prepare, many evacuees left without essentials. As one respondent reported, “I wish the evacuation was made early as I left to pick up kids and couldn’t go back home. I left with no cloth[e]s or anything.”8 Many ran out of gas en route, many were unsure of the correct route on Highway 63, many were separated from family members, and many lacked sufficient food or water during their drive. Fear was prevalent as the evacuees, with the fire burning all around them, struggled to escape. As one survey respondent put it, “I hope it is something I never have to experience again. […] Sitting in stand-still traffic watching fire coming towards you is something no one can imagine until you go through it.”9 Another commented,

___________________

2 Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo. (2016, May 3). Media briefing: Wood Buffalo Forest Fire update – May 3, 11 a.m. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=55O3jp8thKM

3 McGee, T. K. (2019). Preparedness and experiences of evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Horse River wildfire. Fire, 2(1), 13.

4 McGee, T. K. (2019). Preparedness and experiences of evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Horse River wildfire. Fire, 2(1), 13.

5 McGee, T. K. (2019). Preparedness and experiences of evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Horse River wildfire. Fire, 2(1), 13.

6 Respondent #216, cited in McGee, T. K. (2019). Preparedness and experiences of evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Horse River wildfire. Fire, 2(1), 13.

7 McGee, T. K. (2019). Preparedness and experiences of evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Horse River wildfire. Fire, 2(1), 13.

8 Respondent #425 cited in McGee, T. K. (2019). Preparedness and experiences of evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Horse River wildfire. Fire, 2(1), 13.

9 Respondent #31 cited in McGee, T. K. (2019). Preparedness and experiences of evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Horse River wildfire. Fire, 2(1), 13.

“We had to literally drive through mountains of flames to make it out. […] If we had to stop or slow down, we would have died in our car.”10

McGee’s research found that while some evacuees stayed in one host community until they could return home, 60 percent moved multiple times. In many cases they initially found themselves staying with family or friends, but then moved on when they felt they had overstayed their welcome. Additionally, they stayed in various other types of accommodation, such as rental rooms or properties, hotel rooms, or campers, with some even living for a time in a vehicle of one kind or another. Evacuees received help from numerous sources, including friends, family, strangers, aid organizations, the Government of Alberta, and local businesses. These various forms of assistance came their way as people were starting to leave, with some even getting rides from strangers, and continued as they traveled and ended up staying in safe places.

In response to McGee’s questions about the help they received, many evacuees mentioned encountering, stationed along the highway, people handing out food and water,11 with some even driving up from Edmonton to assist. Respondents mentioned that along the route “people were amazingly kind and helpful, going out of their way to do whatever they could to help and accommodate us.”12

Revisiting the key questions being considered as part of the session, McGee said she has concluded that unique aspects of this case study involve the following elements: the extreme nature of the fire as well as the community’s location in the flammable boreal forest with only single highway access, there being only one way in and one way out of the various neighborhoods. In terms of the problems that occurred, she pointed out that many residents, including the municipality as a whole, were not well prepared. People were told to carry on as usual and many people were at work or in school on May 3. At the same time, many chose to evacuate without receiving an official evacuation order because they saw homes burning or were told by others to leave.

One lesson learned, McGee said, is the need to emphasize the importance of involving land use planners in wildfire management in order to address single-road access issues. It is also crucial, given a potential need to evacuate, to warn populations well in advance so they can be prepared.

THE WOOLSEY WILDFIRE

Robert Taylor, Fire GIS Specialist, U.S. National Park Service13

Less than 24 hours before the Woolsey Fire began on November 8, 2018, there was a mass shooting that left 12 dead and 16 injured at a nightclub in nearby Thousand Oaks, California.14 The Woolsey Fire was the largest in the Santa Monica Mountains’ recent history, three times the size of the 1993 Green Meadow Fire, which had held the record since 1993.15 Beginning at 2:24 p.m., it was started by a power line spark from a substation on The Boeing Company’s property in the Santa Susanna Field Lab in the Simi Hills. It took 14 days to contain and burned 87 percent of the National Park Service land in the area and 47 percent of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area.16

The fire occurred in southern California, with the coast to its south, agricultural land to the west, and towns including Thousand Oaks, Los Angeles, and Santa Monica to the north. The east end of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area reaches into dense downtown Los Angeles. The fire initially jumped the U.S. Route 101 freeway near what is now the site of a new wildlife overpass.

___________________

10 Respondent #49 cited in McGee, T. K. (2019). Preparedness and experiences of evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Horse River wildfire. Fire, 2(1), 13.

11 McGee, T.K. (2019). Preparedness and experiences of evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Horse River wildfire. Fire, 2(1), 13.

12 Respondent #416 cited in McGee, T. K. (2019). Preparedness and experiences of evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Horse River wildfire. Fire, 2(1), 13.

13 GIS = geographic information systems.

14 Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2018). Active shooter incidents in the United States in 2018. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-in-the-us-2018-041019.pdf/view

15 CAL FIRE. (2024). Historic fire perimeters. https://www.fire.ca.gov/what-we-do/fire-resource-assessment-program/fire-perimeters

16 U.S. National Park Service. (2023). 2018 Woolsey Fire—Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area. https://www.nps.gov/samo/learn/management/2018-woolsey-fire.htm

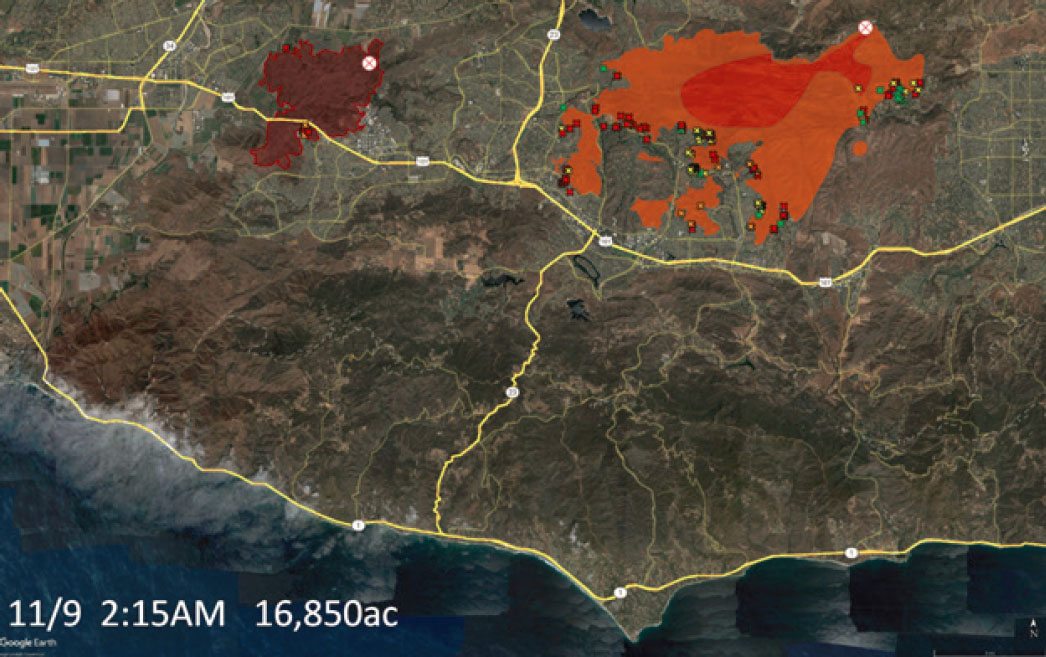

Taylor shared an overhead-projection perspective from Google Earth to show how the fire progressed, helping outside observers visualize the fire’s overall behavior. See Figure 5-1 for a map, showing the Hill Fire on the left and the Woolsey Fire on the right. He pointed out that although it may appear as if the fire spread in clean polygons, the reality was much more chaotic. It spread mainly through windborne embers, over time creating numerous smaller fires that merged into larger ones.

At 2:03 p.m. there was a small ignition in Hill Canyon, which started the Hill Fire. The Ventura County Fire Department immediately dispatched strike teams, but within 15 minutes, the fire outflanked them and jumped the 101 freeway. Just over 20 minutes later, the Woolsey Fire ignited west of Woolsey Canyon Road and rapidly spread from the Santa Susanna Field Lab.

Santa Ana winds and red flag conditions—characterized by low humidity and strong northeast winds of 20 to 25 miles per hour, with gusts of up to 55 miles per hour—drove the fire. Taylor noted that despite the fire department’s preparedness, the fire spread rapidly. By 9:15 p.m., a few hours into the evening, the Hill Fire started stalling out in the light 5-year-old fuels of the Springs Fire footprint. But the Woolsey Fire was off to the races, with many people and much property in harm’s way. L.A. and Ventura County sheriffs started issuing evacuation orders. The fire continued to spread rapidly. By 2:15 a.m. it was crossing over into Thousand Oaks, with dozens of houses engulfed in flames before first responders could even arrive.

By 5:00 a.m., the fire had reached the 101 freeway, a crucial point where firefighters hoped to hold the line. Taylor observed that firefighters believed the 101 freeway—which is primarily an eight-lane highway, with up to ten lanes in some places—was the best possible place to make a stand against fires in this region. Sometimes they

NOTE: The colored X corresponds with green = affected (1–9%); yellow = minor (10–25%); orange = major (26–50%); red = destroyed (51–100%).

SOURCE: Images created using Google Earth. Workshop presentation by Robert Taylor, June 13, 2024 (slide 17).

have succeeded, for example in the 2005 Topanga Fire,17 but not this time. When the fire first spotted18 across the freeway at Cheeseboro Road, they caught it, but when it spotted across Liberty Canyon onto a hill that was in alignment with the winds, it quickly spread. Within hours, the situation was out of control.

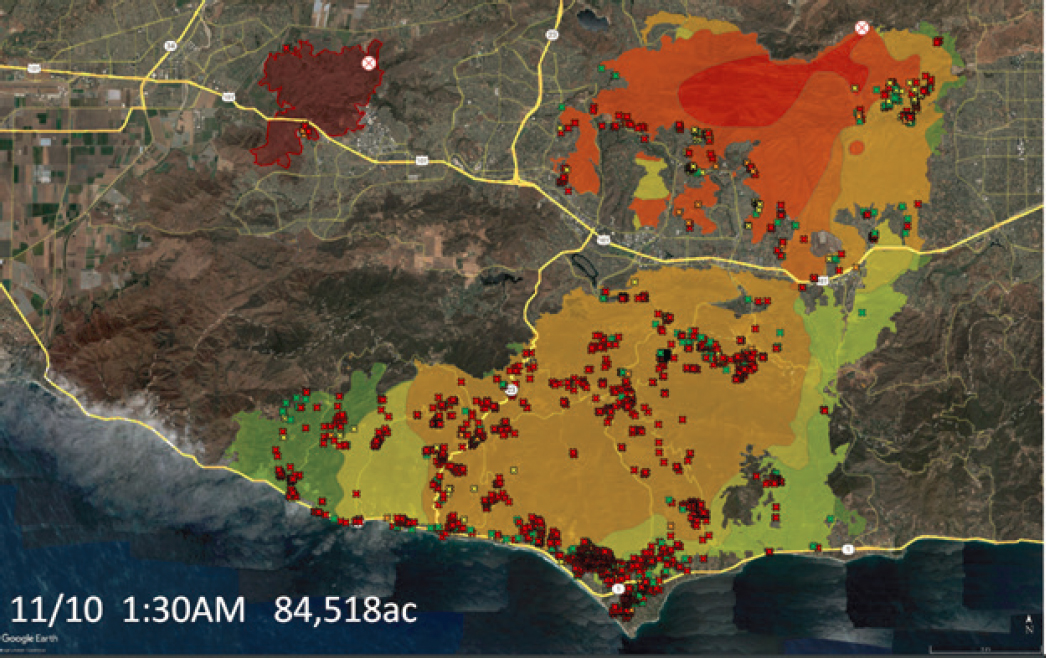

By 11:00 a.m., just six hours later, the Woolsey Fire had spread 11 miles from the 101 freeway to the beach, engulfing more than 1,000 homes. Tragically, several people died, including one person fleeing on foot and two in a car. Despite attempts to contain it, the fire continued to spot across the 101 freeway—which occurrence, Taylor emphasized, demonstrates that an eight-lane freeway is no barrier against wildfire spread in Santa Ana winds. Embers were traveling through the air up to a mile and a half ahead of the front of the fire, a phenomenon that is commonly observed in weather-driven wildfires. By 11:30 a.m. the head of the fire reached the beach—which as Taylor pointed out, firefighters ironically refer to as “the Great Pacific fire break.”

By 1:00 p.m., the fire had spread still further, now covering almost 70,000 acres. Since containing fire spread was generally impossible in the prevailing weather, firefighters focused on point protection (i.e., protecting individual structures where possible) and helping local law enforcement implement the evacuation order to protect human lives. County sheriffs ordered nearly a quarter-million people to evacuate.19 By 1:30 a.m. on November 10,

NOTE: The colored X corresponds with green = affected (1–9%); yellow = minor (10–25%); orange = major (26–50%); red = destroyed (51–100%).

SOURCE: Images created using Google Earth. Workshop presentation by Robert Taylor, June 13, 2024 (slide 17).

___________________

17 Cullom, K. D. (2005, December 1). The Topanga Fire. FireHouse. https://www.firehouse.com/operations-training/article/10503600/the-topanga-fire

18 “Spotting” occurs when embers land on the unburned side of a fireline. More information about spotting is available at https://www.nwcg.gov/publications/pms437/crown-fire/spotting-fire-behavior

19 County of Los Angeles. (2019, November 17). After action review of the Woolsey fire incident. https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/supdocs/144968.pdf

moving westward with the northeast winds, the fire had overspread almost 85,000 acres (see Figure 5-2). It had by this time caused an urban conflagration, destroying 800 structures in one area.

The Santa Ana winds produced extreme fire behavior that overwhelmed available fire suppression resources. Many houses burned despite the creation and maintenance of defensible space along the edge of communities, because fire suppression resources were spread too thin and simply could not be everywhere at once.

On November 11, a temporary break in the weather brought a southwest breeze. Unfortunately, being hot and dry, this did not provide much relief. The next day the Santa Ana winds resumed, and the fire continued to spread. However, at that point, the fire had moved into areas with younger vegetation that had grown after the 2013 Springs Fire. This vegetation, which lacked the fuel load of other areas, as well as the local terrain—which to some degree blocked the winds—helped slow the fire, allowing firefighters to gain control. By the end of November 12, the major fire spread was contained, but it took a full 14 days to declare the fire fully contained.

Impacts from the Woolsey Fire included three deaths, 2,033 destroyed or damaged structures, over 250,000 people evacuated for up to 12 days, and total property damage estimated to have exceeded $6 billion.20 The total suppression costs for the Woolsey Fire were approximately $52 million, involving thousands of firefighters and extensive air attacks.21

A significant issue that Taylor highlighted was how resources had been sent to northern California to assist with the Camp Fire, which started a few hours before the Woolsey Fire.22 This left fewer resources available to tackle the Woolsey Fire, resulting in extensive damage even before responders could arrive. What helped provide a tactical advantage for firefighters, he said, was in those cases where defensible space around homes had been maintained.

Because the National Park Service monitors wildlife as well, Taylor explained that two of 13 collared pumas were lost during the Woolsey Fire. P-74, a young male, was completely consumed by the fire. P-64, known as “The Culvert Cat” for his method of crossing under freeways, is thought to have died as a result of burns, dehydration, and starvation after the fire.

Additionally, the fire had dramatic short-term impacts on stream channel geomorphology, with the heavy sediment, mud, and ash filling pools and disrupting aquatic life. Along with disrupting the reproduction of any number of amphibians, fish, and aquatic invertebrates, the fire affected the red-legged frog, a threatened species present in small numbers at several reintroduction sites. On the positive side, Taylor noted, post-fire sedimentation can benefit riparian tree establishment, aiding species such as sycamores and cottonwoods. The main channels tend to flush out over several years, and this can help recharge gravel beds that provide spawning habitat for fish like steelhead trout—although these fish have yet to return to several local streams that supported them historically.

Key takeaways from Taylor’s comments included the recognition that weather drives big fires, limiting the effectiveness of fuel treatment programs. While defensible space around homes can be effective if defended, strategic fuel treatments have limited success in stopping weather-driven wildfires. Because of long-range ember transport and spot fires, nothing on the ground is very effective at stopping the head of a weather-driven wildfire.23 He said fire prevention remains crucial, and efforts such as, for example, burying power lines and armoring roadsides have the potential to significantly reduce fire starts. Southern California Edison has begun burying power lines in key areas, a long-discussed measure. Since more than half of fires start along roadsides,24 Taylor suggested that modest roadside armoring could prevent many fires.

___________________

20 Holland, E. (November 28, 2018). $6 billion in real estate destroyed in Woolsey fire: Report. Patch Media. https://patch.com/california/malibu/6-billion-real-estate-destroyed-woolsey-fire-report

21 County of Los Angeles. (2019, November 17). After action review of the Woolsey fire incident. https://file.lacounty.gov/SDSInter/bos/supdocs/144968.pdf

22 More information about the 2018 Camp Fire is available at https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2021/02/new-timeline-deadliest-california-wildfire-could-guide-lifesaving-research

23 However, Taylor noted that strategic fuel treatments sometimes help wildland firefighters stop fire spread on the flanks of a fire. For example, at Malibu Creek State Park along Las Virgenes Canyon Road, firefighters successfully held the fire at a strategic fuel treatment area, demonstrating their potential effectiveness.

24 Keeley, J. E., & Syphard, A. D. (2018). Historical patterns of wildfire ignition sources in California ecosystems. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 27, 81–799.

MAUI FIRE DISASTER: PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS AND RESEARCH TRAJECTORIES

Karl Kim, Professor, University of Hawai’i at Manoa

Planning is not just about turning knowledge into action, Kim pointed out, but also about broadening choices and considering alternatives. He said it is also about connecting ends and means while managing uncertainty across disciplines and at different spatial and temporal scales. Planning aims to “do good and be right,” with context being crucial. Fires are connected to climate; decadal, annual, and seasonal oscillations; synoptic storms; and local impacts. Conditions such as severe drought, an El Niño, several La Niña years of built-up vegetation, and high winds, can lead to wildfires rapidly spreading.

Climate and weather-related impacts have increased both financial and human costs.25 Hawai’i’s Maui fire, which destroyed the town of Lahaina,26 was the deadliest wildfire in the United States in over a century27 with an estimated 100 fatalities and over 1,000 injuries.28 Kim said uncertainties remain about the true number of fatalities and injuries, including impacts on pets and other species.

Based on building footprints, mapping has found that the fire destroyed 2,142 structures and burned 2,777 vehicles (though Kim noted that this provides only a partial picture). Although more than 5,000 people were displaced or sheltered, many uncertainties regarding the exact number affected remain, due not only to the large number of tourists attracted to the area but also to the pre-existing houseless population.29 Job losses exceeded 10,000, with $13 million in visitor spending lost each day.30 This disaster resulted in billions of dollars in property damage, lost livelihoods, and reduced tax revenues.31

Hurricane Dora was about 700 miles south of the island before the fire started, and there continues to be some controversy, Kim pointed out, about the level of influence that the hurricane, combined with a high-pressure system to the north, had on the fire. Native Hawaiians named these winds, which is important Indigenous knowledge to be captured, he stressed. Satellite images during the Maui fire disaster showed how three or four large simultaneous fires on other parts of the island were overwhelming local capacity. Firefighters did not run out of water, but there was a lack of equipment and personnel to manage the scale of the wildfire.

Being a remote populated island poses unique challenges, including distance from resources and isolation, which limit the potential for mutual aid. Transportation between islands is limited to maritime operations, making mobilization difficult. Despite these harsh conditions, Hawai’i has, for centuries now, survived, persisted, and flourished. With islands offering opportunities for understanding different possible approaches to adaptation and innovation, Kim pointed out how technology can be used to improve design, planning, and settlement patterns. Kim said that after the Maui fire, observers drove through the affected area to capture imagery.

Research at the National Disaster Preparedness Training Center (NDPTC) focuses on integrating satellite imagery, aerial drones, 360-degree cameras, and other GIS data and hazard sources. This imagery can be used for field deployment, integrating various base maps, including those from the California Governor’s office of Emergency Services (Cal OES) and the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire), to tag buildings to help assess initial damage and track recovery progress. Noting how it shows not just streets and infrastructure but also homes and structures, Kim pointed out that it has now integrated detailed LIDAR imagery.

___________________

25 Additional details on the frequency and cost of billion-dollar weather and climate events is available at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/

26 Kerber, S., & Alkonis, D. (2024). Lahaina fire comprehensive timeline report. Fire Safety Research Institute. https://fsri.org/research-update/lahaina-fire-comprehensive-timeline-report-released-attorney-general-hawaii

27 NOAA. (2023). Global climate report. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global/202313

28 Maui Police Department. (2023). Maui strong: Maui wildfires of August 8, 2023, Maui Police Department, preliminary after-action report. http://www.mauipolice.com/uploads/1/3/1/2/131209824/pre_aar_master_copy_final_draft_1.23.245 4.pdf

29 Elliott, D. (2024, February 8). More than 5,000 Maui residents are still displaced after last summer’s fires. NRP. https://www.npr.org/2024/02/08/1230181195/more-than-5-000-maui-residents-are-still-displaced-after-last-summers-fires

30 Gangnes, B. (2023, September 7). Jobless claims reveal staggering employment cost of Maui wildfires. https://uhero.hawaii.edu/jobless-claims-reveal-staggering-employment-cost-of-maui-wildfires/

31 U.S. Fire Administration. (2024, Feburary 8). Preliminary after-action report: 2023 Maui wildfire. https://www.usfa.fema.gov/blog/preliminary-after-action-report-2023-maui-wildfire/

Relating to the role performed by new technologies, Kim emphasized the need to consider justice, equity, and fairness, both horizontally and vertically, especially given widening disparities. Social vulnerability indices—including indices of socioeconomic status, household composition and disability, minority status and language, and housing type and transportation—can be analyzed. Utilizing these indices to analyze the Maui wildfire fatalities reveals that many of them were older adults, mostly male, many with chronic conditions and limited mobility.32 Additionally, the impacts are very uneven across sectors—which is to say, who can afford to restart businesses or work from home versus who lost jobs (a situation, in this case, resembling that seen during the pandemic)? Kim suggested that since national standards may not apply to unique island conditions, more work needs to be done to understand the social vulnerability indices of islands.

Kim conducted a project on sharing behaviors observed during disasters, comparing experiences on islands to those in other settings.33 Islanders show a higher propensity to share resources, which is tied to local culture, social capital, and trust. Given how devastating the Maui Fire was to the infrastructure, at the county’s request, current work at the NDPTC involves focusing on resilience hubs. These hubs need to be pre-staged with goods and infrastructure such as water and communications systems. Since informal spontaneous hubs were around long before FEMA and other formal systems were created, the NDPTC is studying conditions fostering similar post-fire spontaneous hubs that in the future could be used to provide shelter, relief distribution, and other services.

The NDPTC is also looking at connecting these hubs with greenways, which can serve multiple purposes such as improving connectivity to community sites; creating open space and recreation; and creating evacuation routes, fire breaks, and equipment staging.34 Additionally, they provide stormwater management and ecosystem benefits like sediment trapping, runoff management, and flood mitigation. He went on to suggest considering other hazards besides wildfires, such as flooding and tsunamis, when designing these facilities.

Kim pointed out that there are successful cases of adaptation and disaster recovery, for example the Lafitte Greenway introduced after Hurricane Katrina, funded initially by recovery funds and sustained by community action through public, private, and volunteer assets and resources.35 Designed for visitors, residents, and recreation, the Lafitte Greenway connects key activities, jobs, and schools, and is integrated with stormwater management.

Kim stressed that the biggest challenge of all is disaster recovery. Since applying the response framework and systems to recovery is not effective, given how they are fundamentally different from one another, he suggested focusing on recovery specifically. Doing so would involve learning, integrating diverse ideas and sources across fields with different notions of reliability and validity.36 He emphasized the need for more convergence as well as multi-, inter-, and trans-disciplinary work, not just across academic disciplines, but between both the public and private sectors. He concluded by saying it is crucial to learn from cities, from disasters—especially those on islands—and each other.

DISCUSSION: ENGAGING STAKEHOLDERS IN COMMUNITY WILDFIRE MANAGEMENT AND RECOVERY

During the discussion, Francis asked about the types of stakeholders targeted—e.g., local government, neighborhood boards, the Indigenous population, and city officials—that is, about who responded and who proved helpful.

Taylor said that in his experience, the primary stakeholders were the neighbors in the community. Due to a patchwork quilt of land ownership, the National Park Service has spent a lot of time engaging with different enti-

___________________

32 Kim, K., Yamashita, E. Y., & Hamaguchi, M. (forthcoming, 2024). Leave no one behind: Lessons from the Lahaina fire disaster. University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

33 More information about the findings is available at https://hazards.colorado.edu/public-health-disaster-research/sharing-during-disasters-learning-from-islands-preliminary-findings-and-initial-implications-for-action

34 More details on the West Maui Greenway Plan are available at https://mauimpo.org/west-maui-greenway-plan

35 Fields, B., Thomas, J., & Wagner, J. A. (2017). Living with water in the era of climate change: Lessons from the Lafitte Greenway in post-Katrina New Orleans. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 37(3), 309–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16655600

36 Kim, K. (2024). Learning from disaster: Planning for resilience. Routledge.

ties. About 10 years ago, a community wildfire protection plan was developed for the Santa Monica Mountains involving work with approximately two dozen self-identified communities. Many public meetings were held with the intention of sharing information about fire ecology and safety. Some community groups, for example the North Topanga Fire Safe Alliance, took significant steps, such as soliciting funds to remove hazardous trees along evacuation routes in order to make their areas more resilient.

Taylor went on to note that CalRecycle also played a crucial role post-wildfire by efficiently cleaning up debris and hazardous materials. CalRecycle worked with Cal EPA to not only monitor air quality but also hire and supervise local contractors, the overriding aim being to complete the cleanup quickly.

Kim conducted a stakeholder map analysis designed to break down and understand the agencies and levels of government involved in response, recovery, and adaptation. He pointed out that an unexpected challenge concerning the Maui fire had to do with the unanticipated level of disagreement regarding the fire’s causes, who should be responsible for addressing it, the relevant risk reduction strategies, who should fund the response and priorities for putting it out. He went on to say this highlights the need, in this context, for effective conflict management as well as effective deliberation processes. In a recent project, Kim explored how to deliberate on disasters and recovery, which revealed the common desire to build back faster, stronger, greener, and more equitably.37 He pointed out, however, the insufficient processes and technologies for managing these deliberations, especially in the current digital age. Also presenting challenges is the way stakeholders are engaged due to layered contested histories. Pointing out broad-based resource management issues, Kim suggested specific actions that in his view should be taken.

Drawing from experiences tied to the Fort McMurray evacuation, McGee added insights associated with how numerous stakeholders—including residents, First Nations people, industry, and businesses—helped and hosted evacuees. Almost everyone within the host communities, she said, worked together to support the evacuees.

Challenges and Strategies for Coastal Community Wildfire Evacuations

Diana Cooper from FEMA headquarters asked about people who went to the beach in Lahaina to escape the fire. Kim noted that Lahaina is a coastal community, so some people were rescued there, but others did not survive because they went to the water where there were other hazards. Kim also noted the challenges of using the detection alert and warning systems and the potential confusion from turning sirens on, since sirens mean one thing for tsunamis and another for evacuation.

Taylor explained that in California, while parts of the coastline were rocky, some sandy beaches served as safety zones during fires. In some broad sandy areas of the beach, people took their animals to the beach, gathered in large parking lots, and sometimes even surfed during wildfires due to offshore winds.

Fast-moving wildfires make it harder, Taylor pointed out, to protect homes and lives, but less fireline construction will typically occur because the fires are too intense to manage effectively, which results in fewer firelines produced. In contrast, slower-moving fires can allow more time for extensive fireline creation, necessitating significant post-fire rehab work.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Jonathan Fink, Committee Chair and Professor at Portland State University

The Fort McMurray, Woolsey Fire, and Maui Fire case studies aimed to provide a more personal perspective on these significant wildfires, which have reshaped our understanding of the potential scale and locations of such destructive events, Fink said.

McGee began with Fort McMurray, discussing a survey conducted among evacuees. The survey revealed that knowledge before the fire was limited and inaccurate and that attitudes about risk were unrealistic. Fink noted this

___________________

37 Kim, K., & Foley, D. (2014). Report to Kettering Foundation, Disasters and Democracy Project.

kind of social science research is crucial for understanding the information needed to manage forests and wildfires more effectively in the future.

Taylor provided a detailed chronology of the Woolsey Fire, emphasizing the importance of creating more defensible space and focusing on fire prevention rather than merely responding to fires. This theme of proactive measures was reiterated throughout the workshop, Fink pointed out.

Lastly, Fink pointed out that Kim’s discussion of the Maui Fire highlighted the need for comprehensive and forward-thinking strategies in wildfire management.