Social-Ecological Consequences of Future Wildfires and Smoke in the West: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 11 Policy, Funding, and Action

11

Policy, Funding, and Action

Pivoting from what we know and do not know about the socio-ecological consequences of wildfire, Gary Machlis, committee member and professor at Clemson University, moderated the final session by focusing on identifying additional needs with regard to policy, funding, measurement, and evaluation—such as the need for mitigation strategies, insurance, community engagement, and improved evaluation/metric capabilities. Panelists were asked to consider how to explicitly confront what must be done next in the process—that is, once the “additional needs” listed above are identified. The goal is not only to transform scientific studies into usable knowledge and usable knowledge into policy and action, but at the same time to consider how to fund these transformative actions at local, national, and bi-national scales to better address the socio-ecological consequences of wildfire in the West.

STEWARDSHIP AND SOVEREIGNTY: IMPLICATIONS OF CIRCUMPOLAR WILDLAND FIRE

Edward Alexander, Co-Chair and Head of Delegation,

Gwich’in Council International, Yukon, and Northwest Territories

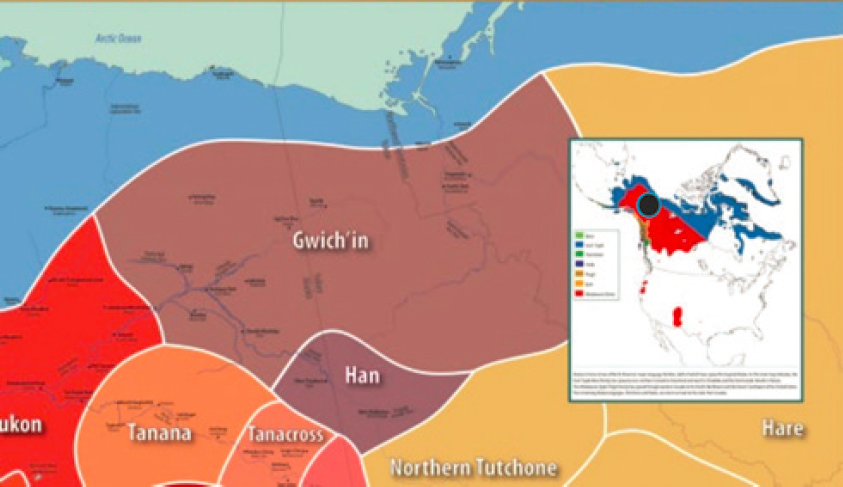

Beginning with an overview of the governance of the Gwich’in Nation, Alexander described how the territory is roughly the size of California. The map in Figure 11-1 depicts the Gwich’in homeland and language areas—which, in this illustration, are not strict political boundaries. In approximate terms, the map shows the region where 10,000 Gwich’in Nation members reside in Alaska, the Yukon Territory, and the Northwest Territory.

Alexander stated that the circumpolar boreal forest, often overlooked, plays a large role in the terrestrial carbon sequestration system. The taiga, or boreal forest, offers essential ecosystem services that support civilization, making it not only significant, but also of international concern.

Alexander has observed that the circumpolar boreal forest has increasingly experienced fires, three times as many taking place each year since 2018 as routinely took place before.1 The 2023 Canadian fires, covering 42.5 million acres,2 were particularly devastating. However, Russia has had several fire seasons that far exceed these

___________________

1 The Global Wildfire Information System (GWIS) is available at https://gwis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/

2 Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre (CIFFC). (2023). Canada Report: 2023 fire season. https://www.ciffc.ca/sites/default/files/2024-03/CIFFC_2023CanadaReport_FINAL.pdf_

SOURCE: Krauss, M., Holton, G., Kerr, J., & West, C. T. (2011). Indigenous Peoples and Languages of Alaska. Fairbanks and Anchorage: Alaska Native Language Center and UAA Institute of Social and Economic Research. Workshop presentation by Edward Alexander June 14, 2024 (slide 2).

in scale (55 million acres in 2003,3 and 74 million acres in 20124), events that, he suggested, are often ignored in North America. He stated that over the last 20 years, more than 200 million acres of boreal forest globally—an area twice the size of California—have burned.5

Impacts of Arctic Amplification

The Arctic has undergone rapid changes, especially in Alexander’s homeland, the Yukon Flats. Since the 1950s, the average temperature has risen by 4.7 degrees Fahrenheit, with winter temperatures increasing by 8.8 degrees since 1950.6 This warming, he pointed out, has resulted in shorter winters and longer summers, leading to less snow, more drying, and extended burning periods. Arctic amplification is significantly impacting the Gwich’in, with 64 percent of their homeland burning between 1960 and 2020.7 During this period, the fire perimeters covered an area equal to four times the size of Delaware.8

Alexander noted that due to the changing climate, across the Arctic fires are increasing in intensity, duration, and area covered. He believes it is crucial to understand the big picture: the boreal forest has sequestered a

___________________

3 More information about the 2003 fire season is available at https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/3858/smoke-from-siberian-taiga-fires

4 More information about the 2012 fire season is available at https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/79161/wildfires-in-siberia

5 This number is an aggregate, primarily adding the largest seasons of Canadian, American (Alaska only), and Russian fires. More information is available at https://www.amap.no/

6 Fox, J., Bertram, M., Guldager, N., Thoman, R., Carroll, H., Brown, R., Lake, B., Grabinski, Z., & Vargas Kretsinger, D. (2021). Yukon Flats changing environment. Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge & International Arctic Research Center.

7 Fox, J., Bertram, M., Guldager, N., Thoman, R., Carroll, H., Brown, R., Lake, B., Grabinski, Z., & Vargas Kretsinger, D. (2021). Yukon Flats changing environment. Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge & International Arctic Research Center.

8 Fox, J., Bertram, M., Guldager, N., Thoman, R., Carroll, H., Brown, R., Lake, B., Grabinski, Z., & Vargas Kretsinger, D. (2021). Yukon Flats changing environment. Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge & International Arctic Research Center.

significant amount of carbon dioxide.9 However, as the forest burns, it is now becoming a net emitter of gases. This shift, Alexander stressed, requires our urgent attention.

The boreal forest sits atop permafrost, which stores more than twice the carbon found in the global atmosphere.10 Additionally, in the Arctic, there is a unique form of permafrost, called Yedoma—these permafrost deposits are found in a small area of the Arctic within Alaska, Russia, and a sliver of Canada—which is no longer stable.11 Unlike regular permafrost, the Yedoma releases a significant amount of its carbon as methane, which is approximately 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period.12

The potential threat is that wildland fires could burn off the insulating layer above the Yedoma, causing it rapidly to release greenhouse gases. Yedoma is mostly water but very fragile. When it collapses, it can form lake-like systems that release methane year-round, unaffected by winter. Additionally, Alexander noted that Yedoma releases not only dangerous methane but also nitrous oxide. Combined, he said that the permafrost and boreal forest are estimated to contain over 3,000 gigatons of carbon—three times the amount released since the Industrial Revolution.13

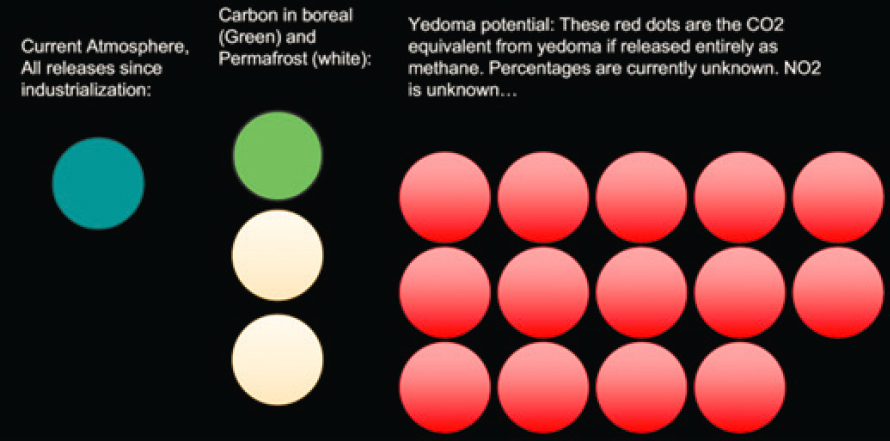

Approximately 25 to 35 percent of the carbon stored in the permafrost (327 to 466 gigatons) is in the Yedoma, which is roughly half of the current amount of carbon in the atmosphere (829 gigatons).14 Alexander shared an example of not only methane flaring from lakes near Fairbanks during winter but also methane bubbles in lakes, which is evidence of year-round production. In Figure 11-2, the color blue represents all emissions since industrialization; green stands for the carbon in the boreal forest; white stands for the carbon in permafrost; and the red dots represent the potential methane emissions from Yedoma. Alexander pointed out that the exact proportions of methane and nitrous oxide releases are unknown.

Fire Management and Conservation Initiatives in the Arctic

Alexander discussed the coordination needed for wildland fire management, emphasizing that this situation necessitates urgent action. Gwich’in Council International is managing two active projects focusing on fire and related issues: ArcticFIRE at the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF),15 and the Circumpolar Wildland Fire Project.16 The Arctic Council’s Norwegian Chairship Wildland Fires Initiative17 is an international effort to raise awareness of the circumpolar and global implications of this issue. Numerous events and activities have

___________________

9 Schädel, C., Bader, M. K.-F., Schuur, E. A. G., Biasi, C., Bracho, R., Čapek, P., De Baets, S., Diáková, K., Ernakovich, J., Estop-Aragones, C., Graham, D. E., Hartley, I. P., Iversen, C. M., Kane, E., Knoblauch, C., Lupascu, M., Martikainen, P. J., Natali, S. M., Norby, R. J., O’Donnell, J. A., Chowdhury, T. R., Šantrůčková, H., Shaver, G., Sloan, V. L., Treat, C. C., Turetsky, M. R., Waldrop, M. P., & Wickland, K. P. (2016). Potential carbon emissions dominated by carbon dioxide from thawed permafrost soils. Nature Climate Change, 6, 950–953.

10 More information about the role of permafrost is available at https://climate.mit.edu/explainers/permafrost

11 Douglas, T. A., Hiemstra, C. A., Anderson, J. E., Barbato, R. A., Bjella, K. L., Deeb, E. J., Gelvin, A. B., Nelsen, P. E., Newman, S. D., Saari, S. P., & Wagner, A. M. (2021). Recent degradation of interior Alaska permafrost mapped with ground surveys, geophysics, deep drilling, and repeat airborne lidar. The Cryosphere, 15(8), 3555–3575.

12 Schuur, E. A., McGuire, A. D., Schädel, C., Grosse, G., Harden, J. W., Hayes, D. J., Hugelius, G., Koven, C. D., Kuhry, P., Lawrence, D. M., Natali, S. M., Olefeldt, D., Romanovsky, V. E., Schaefer, K., Turetsky, M. R., Treat, C. C., & Vonk, J. E. (2015). Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature, 520(7546), 171–179.

13 Schuur, E. A., McGuire, A. D., Schädel, C., Grosse, G., Harden, J. W., Hayes, D. J., Hugelius, G., Koven, C. D., Kuhry, P., Lawrence, D. M., Natali, S. M., Olefeldt, D., Romanovsky, V. E., Schaefer, K., Turetsky, M. R., Treat, C. C., & Vonk, J. E. (2015). Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature, 520(7546), 171–179. See also: Hugelius, G., Strauss, J., Zubrzycki, S., Harden, J. W., Schuur, E. A. G., Ping, C.-L., Schirrmeister, L., Grosse, G., Michaelson, G. J., Koven, C. D., O’Donnell, J. A., Elberling, B., Mishra, U., Camill, P., Yu, Z., Palmtag, J., & Kuhry, P. (2014). Estimated stocks of circumpolar permafrost carbon with quantified uncertainty ranges and identified data gaps. Biogeosciences, 11(23), 6573–6593.

14 Fox, J., Bertram, M., Guldager, N., Thoman, R., Carroll, H., Brown, R., Lake, B., Grabinski, Z., & Vargas Kretsinger, D. (2021). Yukon Flats changing environment. Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge & International Arctic Research Center.

15 More information about the ArcticFIRE project is available at https://www.caff.is/work/projects/arctic-wildland-fire-ecology-mapping-and-monitoring-project-arcticfire/

16 More information about the Circumpolar Wildland Fire Project is available at https://eppr.org/projects/circumpolar-wildland-fire-project/

17 More information about the Norwegian Chairship Wildlands Fires Initiative is available at https://arctic-council.org/news/norwegian-chairship-arctic-wildland-fires-initiative/

SOURCE: Created by Edward Alexander. Workshop presentation by Edward Alexander, June 14, 2024 (slide 2).

taken place to share information and examine concerns about Yedoma, the boreal forest fires, and permafrost.18 The Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge has implemented the first carbon-based fire-fighting strategy in the country to protect Yedoma.19

Additionally, the Gwich’in themselves have a long history of dealing with wildland fire and cultural burning. The Gwich’in practice cultural fire during a specific time of the year when the grass is present in open areas and snow lines the tree edges, allowing them to create a fire break while the ground still remains frozen. This approach reduces smoke and fire intensity, enabling controlled burns that provide various ecosystem benefits. Cultural burning transforms nutrient-depleted soils and monocultures; increases biodiversity; reduces nuisance insect populations; and enhances habitat for pollinating bugs and migrating birds. Cultural burning also increases the land’s carrying capacity, benefiting species such as moose, which produce more calves in healthier browsing areas. As a result, Alexander stated, Gwich’in lands have become sanctuaries for bird species from around the globe.

Noting that more carbon is released from the soil than in forest fires, Alexander pointed out it is important to understand that approximately one-third of this carbon is above ground, while in the northern regions two-thirds resides below ground.20 Stressing the need for shared responsibility and collective action to spur research on the Yedoma wildland fire interface, he said engaging with wildland fire in the Arctic requires a multifaceted approach that should include incorporating Indigenous knowledge and cultural burns. He called for not only inspiring more people to research wildland fires in the Arctic—but also for addressing the amplifying climate feedback loop of Arctic wildfires and permafrost melt. Nations and organizations must assert their commitment to this issue, he emphasized, recognizing it as a shared global responsibility.

Alexander noted that research, in the form of co-produced studies, is needed to determine whether Gwich’in cultural burns are carbon-negative. He said in addition there is a need for a Yedoma protection strategy that includes

___________________

18 More details on one example, the Arctic Wildland Fire Sharing Circle that was held in 2021, are available at https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/items/f70cab34-43c7-4c81-89a5-bf984b937901

19 Ruiz, S. (2023, April 17). Fire suppression deployed in Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge to protect carbon. Woodwell Climate Research Center. https://www.woodwellclimate.org/fire-suppression-yukon-flats-national-wildlife-refuge/

20 Ramage, J., Kuhn, M., Virkkala, A.-M., Voigt, C., Marushchak, M. E., Bastos, A., Biasi, C., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., López-Blanco, E., Natali, S. M., Olefeldt, D., Potter, S., Poulter, B., Rogers, B. M., Schuur, E. A. G., Treat, C., Turetsky, M. R., Watts, J., & Hugelius, G. (2024). The net GHG balance and budget of the permafrost region (2000–2020) from ecosystem flux upscaling. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 38(4), e2023GB007953.

considerations for wildland fire across private, state, and federal lands. Furthermore, it is essential, he stressed, to develop global Yedoma policies; to include Yedoma in national inventories developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); and to develop a carbon credit methodology for Yedoma. Alexander concluded by saying an international strategy for Yedoma protection signed onto by the United States, Canada, and Russia is necessary.

NAVIGATING WILDFIRE POLICY AND LEGAL FRAMEWORKS

Michael Wara, Senior Research Scholar, Stanford University

Collaborating with an interdisciplinary team of researchers and lawyers, Wara’s focus spans various domains and involves close collaboration not only with policymakers in California and across the Western United States but also with environmental justice organizations, as well as tribes. He aims to improve policy, including wildfire management, which he discussed from a legal perspective. Wara believes these perspectives are crucial because, fundamentally speaking, the law shapes societal behavior in America. He suggested that changes in wildfire conditions in the West in recent decades have caused increasing tension between the evolving understanding of the system and longstanding legal frameworks.

Wara has observed that, in California, private spending on wildfire risk reduction is often triggered by the sale of new homes and new construction, as well as investments to maintain insurance coverage. On the public side, there is an increasing amount of data pointing to significant imbalances. Public expenditures from electric utilities in California, mainly aimed at preventing utility ignitions, total about $10 billion per year.21 In contrast, he estimated the combined federal and state wildfire response costs from Cal Fire and the U.S. Forest Service to range between $3 and $4 billion annually.22 Cal Fire’s budget includes essential E-Fund expenditures, which are activated during large incidents that escape initial attacks, leading to substantial spending on campaign fires. He noted that the federal government, bolstered by the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), allocates funds for wildfire risk reduction and fuels management—though the U.S. Forest Service’s spending for different states is not transparent. Estimating that approximately $500 million may be spent annually in California, Wara went on to say, “we live in new and uncertain budget times, and as a result, it’s more likely that California will be spending closer to $200 million on wildfire risk reduction related activities moving forward.”

Wara suggested that utility investment in California, aimed at ignition prevention, dominates risk reduction spending. This focus, he said, may contrast with scientific findings that ignitions are heavily influenced by population—and that fuel modification and home ignition prevention are equally important. These alternative investments could not only prevent ignitions but also mitigate the broader societal impacts of wildfires beyond utility costs. Consequently, he said, our current system is unbalanced.

Wara said it is important to consider that utility investments in wildfire prevention may be causing significant societal impacts, particularly for low-income customers. He has observed that many cannot afford their electricity bills and, for this reason, reduce their consumption—some even going so far as to avoid using air conditioning, due to cost concerns, during dangerous heat events. He noted that the electric system’s reliability in high fire-risk areas cannot match that in low-risk urban areas. He feels as though we might need to consider major federal investments in grid infrastructure. Historically, during the Great Depression, rural electrification was achieved through federal investment, which would not have happened based on economics alone. Today, since there is a new risk environment for the utility system, Wara suggested that trying to maintain equal reliability in rural and urban areas—while at the same time keeping electricity rates affordable—is unsustainable.

The disparity between utility ignition prevention and other wildfire risk reduction investments could point to a lack of cost-effectiveness and balance. Wara suggested there is a need not only to develop policies promoting

___________________

21 St. John, J. (2020, February 10). California utilities look to spend $10B reducing threat of grid-sparked fires. Greentech Media. https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/california-utilities-propose-billions-of-dollars-in-wildfire-prevention-plans

22 Farmer, S., & Myers, J. M. (2024, May 14). Economic risks: Forest Service estimates costs of fighting wildfires in a hotter future. U.S. Forest Service. https://www.fs.usda.gov/about-agency/features/economic-risks-forest-service-estimates-costs-fighting-wildfires-hotter

more risk-based planning beyond the utility sector, but also to improve coordination between various funding sources, including utility funds, the general fund, and California’s cap-and-trade revenues. Efforts to push for better risk-based planning outside the utility sphere have largely failed, which he believes is due to a reluctance from agencies governing fire to adopt a risk-based approach. However, this remains a critical area for future work. Progress, Wara said, is expected to occur eventually.

Navigating Legal Complexities in Wildfire Risk Management

Wara shifted focus to the legal context of risk allocation, especially as pertains to private property ownership. He said the most important legal relationship affecting wildfire in the wildland-urban interface involves the legal obligations of real property ownership. In this context, Wara suggested written laws are less important than the liabilities that courts impose during litigation. This includes nuisance, tort, and negligence cases, as well as public sector liabilities like inverse condemnation, where the government may be held responsible for property damage.

Wara’s second point was that private and public entities typically do not make significant investments to prevent negative outcomes unless failing to do so would expose them to substantial liabilities—or the risk of liabilities. Liability decisions are theoretically based on the ability to manage risk effectively. Courts generally impose liability—and lawyers structure private contracts to place risk management responsibility—on the party best equipped to handle it cost-effectively. Wara suggested that historically, legal decisions regarding fire have been disconnected from this framework. In the context of wildfire, liability is attributed solely to the ignition source rather than being shared between the ignition source and the fuels that the fire burns through—an approach that contrasts with our scientific understanding of wildfire.

Wara briefly noted that the federal government currently faces no liability for failing to manage fuels adjacent to communities, as highlighted by the Cary v. United States case.23

The Maui Fire: Potentially Transformative Legal Implications for Landowner Liability

Wara offered his view of the available evidence as suggesting not only that power lines started the fire in Maui that destroyed the town of Lahaina, but also that the fire’s rapid spread was fueled in part by Guinea grass on lands previously used for agriculture. With lands having previously been burned twice a year—subsequently left fallow and “basically neglected”—landowners may have been aware of the fire risk to the community posed by the grass. He said that one potential allegation that could be made by the plaintiff’s attorneys would be that because the landowners maintained their lands in an “unreasonably dangerous condition prior to the fire” they should bear at least partial responsibility.

Wara believes that this key legal question of landowner liability could have transformative implications for those in the mainland United States. The outcome of the Maui fire case will likely influence future considerations of landowner liability, land management practices, and the costs associated with private land ownership in the Western United States.

ECOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT INSIGHTS FROM NCEAS

Cat Fong, Research Associate, National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis

Regarding improved measures and evaluation capacity, Fong discussed the work the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS)24 is doing in this area. A core belief at NCEAS, she said, is in the need for better, consistent, standardized data—that “you can’t manage what you can’t measure.”

___________________

23 Cary v. United States, 552 F.3d 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

24 More information about the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis is available at https://www.nceas.ucsb.edu/

Fong described the development of NCEAS’s Ocean Health Index,25 which assesses the health of oceans worldwide across various social and ecological domains when compared to a baseline. Updated annually and reflecting changes in ocean health, the index serves as an effective management and communication tool, providing scores for every country and using open-access data. Operating on a modest budget of approximately $50,000—and utilizing three interns over a period of approximately 10 weeks—the project, emphasizing transparency and open science, allows stakeholders to track changes and understand specific impacts on ocean health.

Fong said that at NCEAS the latest initiative, paralleling the work of the Ocean Health Index, is the Western Wildfire Resilience Index. This project aims to assess wildfire resilience across western America, integrating into the index concepts of resilience such as resistance and recovery. While still in development, the index will not only assess health and status but also operationalize resilience factors that matter to stakeholders in this domain. Fong mentioned data that may be included, such as “natural ecosystems, biodiversity, infrastructure, and air quality.”

A virtual audience member asked about the recovery indicators for the Western Wildfire Resilience Index. Fong responded by saying the NCEAS is examining between six and 10 domains, and for each domain, the recovery indicators vary significantly. Elaborating, she said they are evaluating diverse plant characteristics in natural ecosystems, such as their ability to resprout or their dependence on fire. They are also assessing landscape connectivity. Each domain, whether social or ecological, will feature distinct indicators. Due to the comprehensive scope across these domains, Fong emphasized it would not be appropriate simply to enumerate them.

Noting the ability to access vast amounts of open data, Fong shared several maps, including one incorporating the global human settlement layer, offering population density estimates down to 10 meters.26 Another example is Microsoft’s dataset showing on a worldwide basis every building’s footprint.27 Integrating this data into a wildfire index could be highly valuable, Fong stated. Additionally, she noted openly available street map data detailing road locations, topology, surface type (e.g., asphalt versus dirt)—and even details such as bridge types and road capacities (e.g., speed limits and vehicle capacity).28 Lastly, she shared detailed street map data, as well as a recent dataset providing tree heights, on a global basis, at one-meter resolution.29

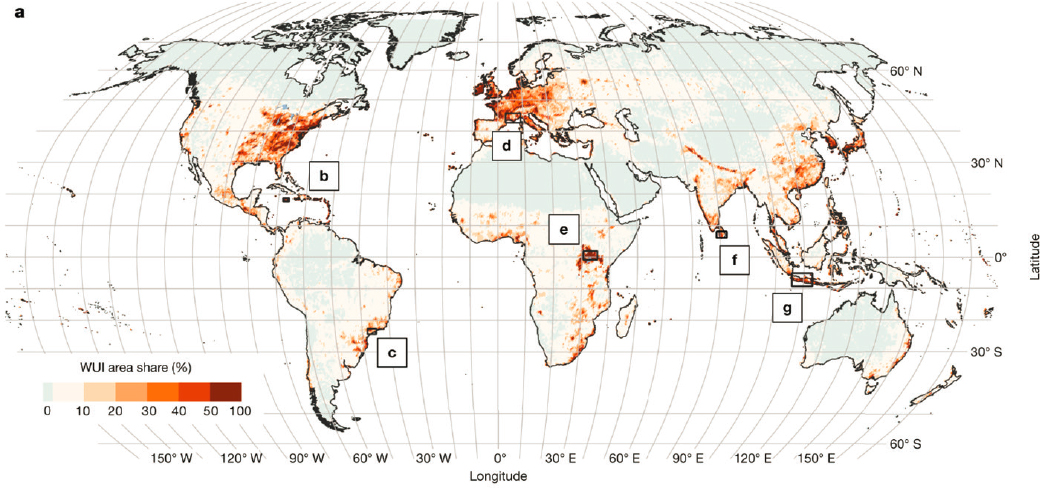

Fong noted there are some continuing debates about what constitutes a Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI). Figure 11-3 combines the global human settlement layer with tree distributions to map the WUI globally at a 10-meter resolution. This dataset provides comprehensive information about areas of risk, locations of structures, population density, and related factors.

Recently, Fong has been exploring aspects of graph theory to analyze questions such as road redundancy, community connectivity, network resilience, and potential evacuation choke points.30 Applying these insights at a landscape scale could be valuable for understanding wildfire contexts. With this data and powerful computing capabilities, she said we can examine defensible space in detail, down to individual parcels and buildings. Fong concluded by saying that by aligning and overlaying various data layers,31 an index can be created that provides a clearer picture of landscape wildfire resilience for different specific settings.

PRIORITIZING WILDFIRE POLICY REFORMS

Machlis began the panel discussion by asking panelists to identify their top suggested policy reforms for addressing the social and ecological impacts of wildfires. Wara highlighted positive smaller efforts in wealthy

___________________

25 More information about the Ocean Health Index is available at https://www.nceas.ucsb.edu/ocean-health-index

26 More information about the Global Human Settlement framework is available at https://collections.sentinel-hub.com/global-human-settlement-layer-ghs-built-s2/

27 More information about Microsoft’s maps is available at https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/maps/bing-maps/building-footprints

28 Anderson, J., Sarkar, D., & Palen, L. (2019). Corporate editors in the evolving landscape of OpenStreetMap. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 8(5), 232.

29 Tolan, J., Couprie, C., Brandt, J., Spore, J., Tiecke, T., Johns, T., & Nease, P. (2024, April 22). Using artificial intelligence to map the Earth’s forests. Sustainability. https://sustainability.fb.com/blog/2024/04/22/using-artificial-intelligence-to-map-the-earths-forests/

30 Boeing, G. (2020). A multi-scale analysis of 27,000 urban street networks: Every US city, town, urbanized area, and Zillow neighborhood. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 47(4), 590–608.

31 Kolios, S., Vorobev, A., Vorobeva, G., & Stylios, C. (2017). GIS and environmental monitoring: Applications in the marine, atmospheric and geomagnetic fields. Springer.

SOURCE: Schug, F., Bar-Massada, A., Carlson, A. R., Cox, H., Hawbaker, T. J., Helmers, D., Hostert, P., Kaim, D., Kasraee, N. K., Martinuzzi, S., Mockrin, M. H., Pfoch, K. A., & Radeloff, V. C. (2023). The global wildland–urban interface. Nature, 621(7977), 94–99, Figure 1. Workshop presentation by Caitlin Fong, June 14, 2024 (slide 12).

counties, like Napa and Marin, aimed at improving wildfire mitigation through pre-fire investments. He emphasized the importance of sustained funding across all jurisdictions to create resources to build trust, skills, and workforce capacity for wildfire resilience everywhere. Noting the current lack of ongoing sustained state and federal programs, Wara advocated for broader implementation of such programs to support the health and resilience of rural communities.

Likening current efforts to rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic—short-term, localized approaches that do not address long-term needs—Alexander suggested efforts too often focus narrowly on mitigating risks to individual homes. He advocated for a comprehensive national strategy, akin to a Yedoma protection plan, integrated into wildland fire services. He has observed in Alaska a disproportionate allocation where only a small percent of funding addresses wildland fires.32 He not only stressed the importance of rational, strategic steps aligned with real risks, but also called for international collaboration, recognizing that wildfire challenges extend beyond national borders, with different countries holding varying levels of responsibility.

Machlis suggested rebuilding, rethinking, and perhaps reorganizing the U.S. Forest Service, such as parsing out their responsibilities and tasks (e.g., fire control, timbering, recreation).

An audience member queried whether the U.S. Forest Service could glean any lessons from the Department of the Interior on enhancing land management for better wildfire outcomes. In response, a workshop participant noted significant bureaucratic hurdles impeding the Forest Service’s efforts to implement prescribed burns and forest management practices. Drawing on examples such as Liberty Utilities in the Tahoe area, she highlighted how navigating these challenges requires innovative approaches.33 At the same time, she emphasized that hindering the Forest Service’s ability effectively to learn and evolve are bureaucratic constraints and limited organizational adaptability.

___________________

32 Rosen, Y. (2024, June 5). An Alaska wildlife refuge is changing its wildfire strategy to limit carbon emissions. Alaska Beacon. https://alaskabeacon.com/2024/06/05/an-alaska-wildlife-refuge-is-changing-its-wildfire-strategy-to-limit-carbon-emissions/?

33 U.S. Forest Service. (n.d.). Liberty Utilities resilience corridors. https://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=55882

BROADENING LIABILITY AND RESPONSIBILITY: REVISITING FIRE LITIGATION STRATEGIES AND LAND MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTABILITY

Regarding targeting the deep pockets of utility companies, an audience member raised a pertinent question about whether this is influenced by the number of fatalities and other affected groups? He also questioned why the focus is exclusively on such entities, suggesting that those responsible for land management should also be held accountable. This discussion reflected the concept that “the legal tail wags the planning dog” in the way that legal considerations sometimes overshadow planning priorities. While such challenges can spur reforms, the audience member was particularly interested in Wara’s main takeaway from this complex situation.

Wara noted the involvement of several parties, including Maui County, which owns land affected by the fire’s rapid spread. He said this case is unusual, distinctively so, because fire litigators typically target large utilities that have substantial financial resources. However, Hawaiian Electric serves a smaller area, and the scale of liabilities from the fire, particularly in terms of structure loss, is significant. It seems improbable, Wara stated, that the utility can absorb these costs or transfer them to customers without overcoming significant hurdles. He said a look at how utilities, like those serving Marin County, have managed similar situations could provide some precedent—but Hawaiian Electric faces a challenging road ahead. There is the possibility of exploring shared responsibility, but this raises complex questions. Holding landowners accountable could have unintended consequences, such as affecting land trusts that lack funds to maintain conservation lands—or impacting timberlands that are often managed less responsibly due to cost considerations. These unintended consequences could lead to scenarios where lands are abandoned or sold for other uses. Because it is a complicated issue that needs careful consideration, Wara said it might be necessary in the future to attract private investment and ensure safer, more responsible land management around communities.

UNIFICATION IN THE ARCTIC COUNCIL

Jonathan Fink, Planning Committee chair, said to Alexander that he found his remarks about the new risks posed by Arctic wildfires, such as the release of methane from the burning of the permafrost, quite compelling. Considering that much of the territory affected is in Russia, and knowing as we do that Russia has not been proactive on climate change, Fink wondered if Russian members of the Arctic Council perceive this issue as significant enough to prioritize at the national level?

Alexander explained that during the Russian reinvasion of Ukraine, the Arctic Council’s activities were paused due to a halt in all diplomatic relations with Russia. Previously, during the Arctic Council cycle in Finland, the United States objected to including the words “climate change” in the Rovaniemi Declaration,34 resulting in the absence of such a declaration for the first time in Arctic Council history. Despite this, Russia did not oppose the inclusion of the words “climate change” in discussions. Alexander went on to discuss the challenges associated with obtaining accurate data from Russia, noting that much of the information available on wildfires in Russia can be unreliable. He highlighted the importance of ground-truthing data and having third-party verification for wildfire and other environmental data coming out of Russia. Though maintaining cohesion within the Arctic Council has been challenging amid geopolitical tensions, Alexander emphasized that efforts around wildfire issues have served as a unifying initiative across all Arctic nations, despite differing views.

ADAPTING TO A FUTURE WITH INCREASED WILDFIRE AND SMOKE: STRATEGIES AND PERSPECTIVES

Committee member Alexandra Paige Fischer queried how communities might adapt to increased fire and smoke in the future? She asked whether the response would involve merely coping—or if there were potential scenarios such as retreating from fire-prone areas, retrofitting homes to withstand fire and smoke, adjusting livelihoods to minimize outdoor work, or restructuring power systems?

___________________

34 More information about the Rovaniemi Declaration is available at https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/items/6d8915de-6345-483d-a97e-17d4dd2eea39

Alexander described wildland fire as a significant concern not only for various ecosystems, including the services they provide, but also for humanity’s future. He expressed a sense of urgency, noting that the data he presented on wildfires are neither accounted for in existing projections, nor are they included in national inventories. Without effective management informed by both scientific knowledge and Indigenous practices, such as cultural burning, he warned that atmospheric CO2 levels could rise rapidly, potentially reaching 800 ppm. Highlighting the immediate threat in the North, he suggested it could exacerbate global climate issues. Additionally, he pointed out the overlooked issue of smokeless emissions, which could be substantial, occurring in the years following wildfires. To effectively address these pressing challenges, Alexander emphasized the need for informed policies and deeper scientific inquiry.

Wara acknowledged shared concerns about the Arctic. He sees the current moment as pivotal, suggesting there is a window of about 10 to 15 years to effectively address the challenges. Getting it right, in his view, would involve not only developing strategies to tolerate higher levels of fire—ideally low-intensity fires—but also restoring a diverse fire pattern known as a fire mosaic, which over the past century has been lost in many parts of California.

He emphasized the importance of, simultaneously, fostering community trust and relationships to modify existing communities in ways that would increase their resilience to wildfires. Pointing out that this goal is achievable, Wara said he believes it is a less daunting challenge than reducing the intensity of hurricanes in the southeastern United States. Success, he argued, hinges on commitment, trust-building, and adequate resources.

Fong expressed optimism about the wildfire issue when compared to ocean-related challenges. Emphasizing that we are in an era with unprecedented access to information and knowledge exchange, she took a cautious stance but saw reason to be optimistic as transparency and community access to decision-making processes improve.

STRATEGIC CONCERNS AND NATIONAL SECURITY IMPLICATIONS OF WILDFIRES

An audience member, Steve Jensen of California State University at Long Beach, asked about the national security implications of wildfires, noting a case garnering attention from the intelligence community—and included even in the President’s daily briefing—involving the use of fire retardants, and its potential environmental impacts in Montana. Suggesting that wildfires could act as a multiplier of existing unrest, he emphasized the potential for intentional multiple wildfires, whether started by an internal actor or someone from the outside, to overwhelm incident management capabilities and become a national security threat. More broadly, Jensen was interested to hear the panel’s consideration of the national security implications of wildfires.

Machlis pointed out that, historically, there is a case where at the beginning of World War II the Japanese employed wildfire as a military tactic in the American West. They attempted to ignite numerous fires to create chaos and distract from war efforts. While the strategy ultimately failed, Machlis said it stands as a notable historical instance of military tactics that rely on wildfire being used in the American West.35

Wara said that we are entering an era where the threat from wildfires is likely to surpass our ability to handle them. A poignant example of this was during the Woolsey Fire when, on the same day, the Camp Fire also erupted, stretching thin Cal Fire’s formidable air force. When this happened, tough decisions had to be made about resource allocation. Moving forward, we could face challenging tradeoffs on an increasing basis where we will be forced to prioritize which fire receives resources and which does not. Wara emphasized this could mean we will not be able to afford the level of response capabilities that have historically been relied upon.

Alexander said he does not believe military solutions are the answer. He supports instead the need for not only scientific solutions but also civilian sector leadership devoted to addressing wildland fires in ways that go beyond military approaches. An example of what was initially a militarized approach was Sweden’s response about six years ago to its major wildfires.36

___________________

35 For more information see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fu-Go_balloon_bomb

36 Braw, E. (2018, July 31). Sweden’s raging forest fires show the value of allies. Defense One. https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2018/07/swedens-raging-forest-fires-show-value-allies/150168/

LEGAL LIABILITY AND FUEL MANAGEMENT: BALANCING FIRE SUPPRESSION WITH CONSERVATION GOALS

Glen MacDonald, a speaker, thanked Alexander for highlighting the reciprocal relationship between forest management and climate change impacts on carbon budgets. Saying he feels it is crucial to recognize that this interaction goes both ways, MacDonald, moving on to comment about legal liability for fuel management, mentioned SB 332 in California,37 which addresses liability related to prescribed burns. This legislation stipulates that if people conduct a prescribed burn and are grossly negligent, they can be held responsible for fire-fighting suppression costs. This raises complex issues: If landowners are mandated to manage land solely for fire suppression, what implications are there for conserving endangered species, carbon sequestration, and ecological services like erosion control? This approach might be feasible in grasslands in Maui, he said, but extending it across diverse ecosystems in the West could potentially lead to a biodiversity catastrophe. Suggesting that these are significant considerations, MacDonald said they need careful navigation within existing regulatory frameworks.

Wara noted that S. bill 332, compared to previous laws, reduced liability risks for burners. Previously, burners and landowners could be held liable for simple negligence—but now they are only liable for “gross negligence.” This change, officially recognizing for the first time cultural burning under California state law, has encouraged more prescribed burning. If landowners were held partially liable due to inadequate fuel management, this law would not necessarily lead to drastic landscape alterations, such as clearing entire areas like transmission line easements. Instead, the legal standard of negligence requires a reasonable duty of care, not perfection. This means, Wara noted, taking reasonable precautions to prevent unreasonably dangerous situations—rather than requiring flawless management.

EXPLORING ALTERNATIVES TO GEOENGINEERING FOR BOREAL WILDFIRE EMISSIONS

In response to an audience member’s question on whether geoengineering is a possible solution for boreal wildfire emissions, Alexander mentioned he has encountered numerous ambitious geoengineering proposals, often submitted by companies based in California, advocating strategies such as deploying reflective materials across the Arctic. However, he finds these approaches potentially more detrimental than beneficial. He said solutions lie instead within Indigenous communities, emphasizing the need to revive practices that have sustained the largest carbon sequestration zone, the boreal ecosystem, for millennia. These approaches, akin to a form of geoengineering, promote biodiversity, enhance land-carrying capacity, and serve multiple ecological functions beneficial to both humans and wildlife. In order to mitigate serious risks, Alexander stressed there is a need, moving forward, to broaden discussions beyond anthropocentric viewpoints.

Wara expressed skepticism about geoengineering being, at this time, a viable solution. Over the past two decades, there has been an ongoing debate regarding environmental geoengineering experiments38 that are possibly driven by private philanthropic funding rather than government support, thus introducing additional risks. Wara underscored the importance of being realistic, noting that geoengineering remains far from feasible and could yield significant unintended consequences.

Fink, drawing on his background as a volcanologist and author of a paper on geoengineering,39 expressed agreement with Wara’s assessment. Highlighting the potential adverse effects associated with current geoengineering concepts, he recounted previous proposals—for example, artificially inducing events akin to Mount Pinatubo’s

___________________

37 Civil liability: prescribed burning operations: gross negligence, S. bill 332, 2021–2022 California State Senate. (2021). https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220SB332

38 Low, S., Baum, C. M., & Sovacool, B. K. (2022). Taking it outside: Exploring social opposition to 21 early-stage experiments in radical climate interventions. Energy Research & Social Science, 90, 102594.

39 Fink, J., & Ajibade, I. (2022). Future impacts of climate-induced compound disasters on volcano hazard assessment. Bulletin of Volcanology, 84, Article 42.

eruption.40 Characterizing some proposals as serving the interests of the oil industry rather than genuine environmental stewardship, Fink criticized these proposals as mere distractions from more sustainable practices such as reforestation and urban efficiency improvements.

PERSPECTIVES ON THE GLOBAL CHALLENGES AHEAD

Referring to Wara’s expressed optimism about reducing building loss and casualties in the United States, a virtual audience member raised concerns about the potential severe impact, possibly making the world less habitable, of the increased heating associated with boreal carbon and methane.

Though emphasizing missed opportunities for action, Wara maintained, despite these shortcomings, a basis for optimism due to the successful avoidance of some worst-case scenarios. He pointed to not only global technological advancements but also the reduction of our reliance on coal, which he sees as pivotal for a brighter future. However, he cautioned that some outcomes will be intolerable—particularly for the world’s most vulnerable populations. Wara stressed both the importance of being realistic as well as the need for concerted efforts to mitigate these impacts to the fullest extent possible.

Machlis closed the session by sharing the following phrase: “Optimism is the only moral choice.”

___________________

40 Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. (2011, February 17). Volcano watch—The Pinatubo effect: Can geoengineering mimic volcanic processes? U.S. Geological Survey. https://www.usgs.gov/observatories/hvo/news/volcano-watch-pinatubo-effect-can-geoengineering-mimic-volcanic-processes?