Social-Ecological Consequences of Future Wildfires and Smoke in the West: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 8 The Socio-Ecological Consequences of Wildfires: Challenges, Research Needs, and Gaps in Understanding

8

The Socio-Ecological Consequences of Wildfires: Challenges, Research Needs, and Gaps in Understanding

SITE, SITUATION, AND SOCIAL VULNERABILITY

Susan L. Cutter, Professor, University of South Carolina

Focusing on the social side of the consequences of wildfires in the United States, Cutter started by addressing principles related to the concepts of both site and situation. “Site” refers to the exact location on the Earth’s surface, as well as the physical attributes—e.g., topography, climate, soils, water bodies, flora, and fauna—and influences on hazard exposure. “Situation” pertains to the location relative to its surroundings and other places—e.g., accessibility, connectivity, and proximity—influencing diversity in at-risk places as well as human consequences of exposures. These factors make each place unique and affect its vulnerability, coping capacity, and resilience, Cutter emphasized. Recognizing this, she not only addressed the diverse consequences of hazards and disasters across the United States, but also discussed empirical measurement and evidence for these differences.

Challenge 1: Recognize Diverse Consequences

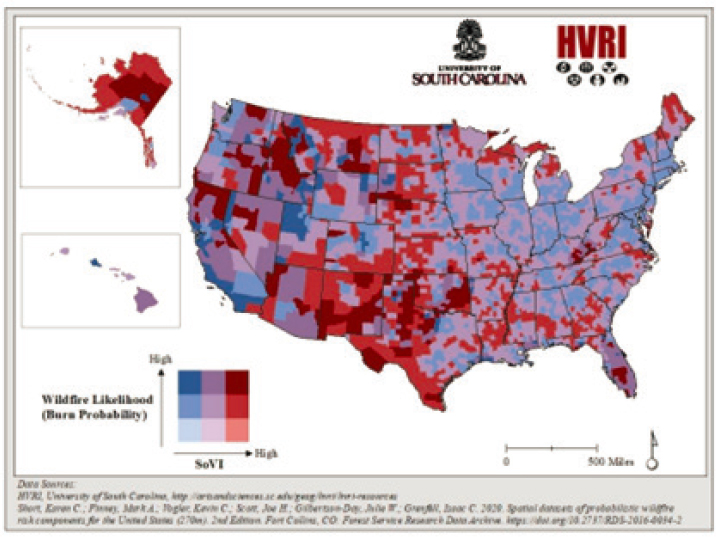

Cutter has observed the increasing use of metrics to assess social vulnerability, which highlights the challenge—as shown in the map in Figure 8-1 comparing the existing social vulnerability with wildfire likelihood—of varying consequences to different populations across the country. The dark red areas indicate regions with both high social vulnerability and high wildfire likelihood. She noted that resilience can be evaluated by examining the capacity of these areas, particularly counties, to cope with such events.

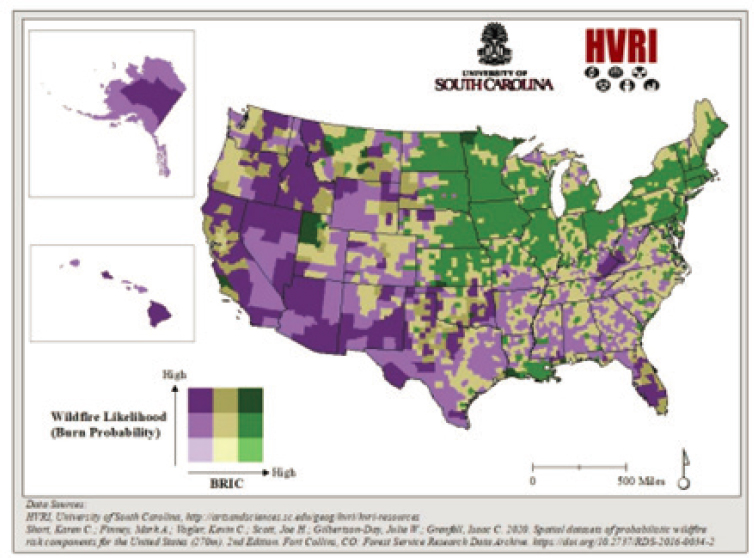

County-level Baseline Resilience Indicators for Communities (CBRIC)1—a baseline index for communities indicating the degree of wildfire likelihood along with the relative capacity of a community to prepare for, respond to, and recover from such events—have been developed and applied to the map in Figure 8-2, dark green areas indicate areas with high wildfire likelihood and high response capacity. She noted this visual representation illustrates the diverse consequences and resilience of different geographical areas.

Cutter compared locations with similar experiences, such as Plumas County, where the 2021 Dixie Fire occurred, and Butte County, where the 2018 Camp Fire took place. Both are low-density areas in California,

___________________

1 More information about these indicators is available at https://sc.edu/study/colleges_schools/artsandsciences/centers_and_institutes/hvri/data_and_resources/bric/index.php

SOURCE: HVRI, University of South Carolina, http://artsandsciences.sc.edu/geog/hri/iri-resources; Short, K. C., Finney, M. A., Vogier, K. C., Scott, J. H., Gilbertson-Day, J. W., & Grenfell, I. C. (2020). Spatial datasets of probabilistic wildfire risk components for the United States (270m) (2nd ed.). Forest Service Research Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.2737/RDS-20160034-2. Workshop presentation by Susan Cutter June 14, 2024 (slide 3).

SOURCE: HVRI, University of South Carolina, http://artsandsciences.sc.edu/geog/hri/iri-resources. Short, K. C., Finney, M. A., Vogier, K. C., Scott, J. H., Gilbertson-Day, J. W., & Grenfell, I. C. (2020). Spatial datasets of probabilistic wildfire risk components for the United States (270m). 2nd Edition. Fort Collins, CO: Forest Service Research Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.2737/RDS-2016-0034-2. Workshop presentation by Susan Cutter June 14, 2024 (slide 3).

with Plumas County having an even lower density (7.8 people per square mile) than Butte County (129 people per square mile).2 She observed that both counties have similar disability rates, but Plumas County has an older population, with 32 percent of households having occupants over 65.3 Despite these similarities, the impacts and consequences differed.

Cutter suggested that Plumas County was already losing population before the fire due to a lack of services for both younger and elderly populations. Suggesting that post-fire recovery was slow partly because Plumas County lacked a post office, she said her visit in May 2023 revealed ongoing trauma and uncertainty in the community. She observed that the greatest need in the community was disaster case management. Recovery efforts were largely driven by one individual who, in their leadership role, was able to unite many people, including the Native American population.

In the Paradise area of Butte County, recovery efforts were led by the Camp Fire Collaborative,4 a collective of community partners and local and regional member organizations. The Camp Fire destroyed nearly 90 percent of the housing stock of Paradise,5 including 36 mobile home parks. Cutter said recovery in Paradise may have been impacted by a criminal settlement with the utility company, Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E), following allegations that the electrical grid had potentially ignited the fire. Residents experienced re-traumatization while navigating the federal recovery process.6 Cutter said this underscores the importance of place, site, and situation in disaster recovery.

Challenge 2: Understand Proximal and Distal Impacts

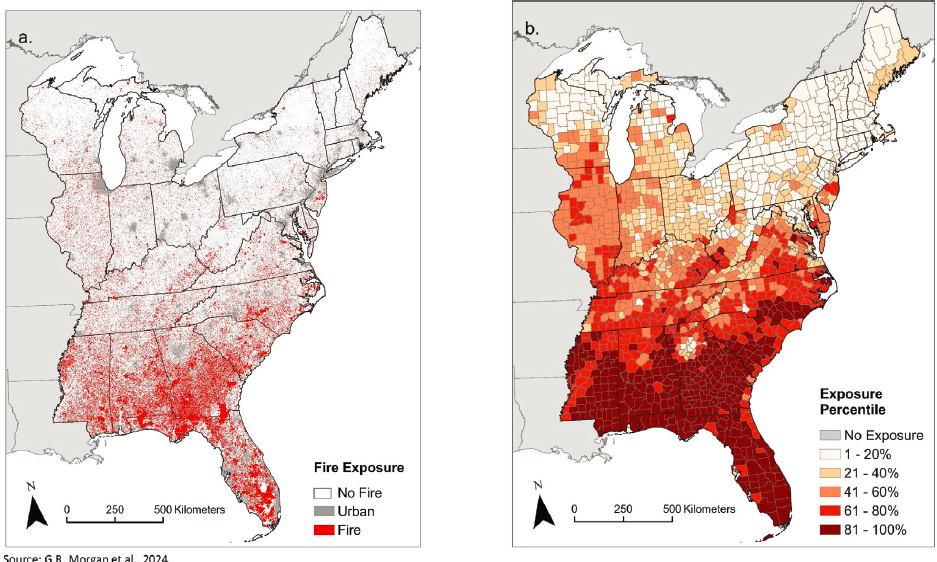

Cutter suggested a second challenge involves understanding the proximal and distal impacts of wildfires. While fires occur in specific locations, elements like smoke can affect areas far away. She has observed that there is a misconception, especially in the eastern United States, that wildfires are only a Western issue. Evidence indicates, however, the need for more focus on wildfires east of the Mississippi River and east of the Rockies’ Front Range.7 Large fires like those near Gatlinburg, Tennessee, do occur in the area.8 Since research shows wildfires in the East are typically small, under 500 acres, this may be the reason they do not appear in large databases. Using remote sensing to detect heat signatures can help identify controlled burns—a primary way, she noted, that fire manifests. Converting this pixel data into county-level information is crucial, she went on to say, since most social data are not point-specific but polygonal. She has observed that this geographic nuance is essential for accurate comparisons.

To compare wildfire exposure with social vulnerability and resilience, Cutter noted that the polygon(s) being used to identify the wildfire-affected area can be compared to social vulnerability and resilience data. She has observed that using this method helps identify disadvantaged places—which is to say, those with high social vulnerability and low capacity to prepare for, respond to, and recover from events like wildfires. In Figure 8-3, the map on the right shows red clusters indicating high concentrations of disadvantaged populations and an increased potential for wildfire exposure. She believes this visualization offers a clear representation of what is at stake that would otherwise require extensive explanation.

Cutter went on to say that by empirically defining disadvantaged populations, we can assess their risk in relation to any threat, including wildfires. In addition, she noted that issues related to distal impacts, such as wildfire

___________________

2 U.S. Census Bureau, QuickFacts, Plumas County, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/plumascountycalifornia,US/PST045223

3 U.S. Census Bureau, QuickFacts, Butte County, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/buttecountycalifornia,US/PST045223

4 More information about the Camp Fire Collaborative is available at https://www.campfire-collaborative.org/

5 Din, A. (2022). What do visualizations of administrative address data show about the Camp Fire in Paradise, California? Cityscape, 3(24), 261–271. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

6 More about the malfunctioning transmission line, the settlement and the recovery process is available at Beam, A., & Rodriguez, O. R. (2023, November 7). Five years after California’s deadliest wildfire, survivors forge different paths toward recovery. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/paradise-wildfire-california-anniversary-five-years-b4434481c38e6a02e9f2d376ac172b04

7 Morgan, G. R., Kemp, E. M., Habets, M., Daniels-Baessler, K., Waddington, G., Adamo, S., Hultquist, C., & Cutter, S. L. (2024). Defining disadvantaged places: Social burdens of wildfire exposure in the Eastern United States, 2000–2020. Fire, 7(4), 124.

8 Associated Press. (2016, November 29). Tennessee flames threaten Dolly Parton’s hotel. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/photo/tennessee-flames-spare-dolly-patron-s-hotel-n689851

SOURCE: Morgan, G. R., Kemp, E. M., Habets, M., Daniels-Baessler, K., Waddington, G., Adamo, S., Hultquist, C., & Cutter, S. L. (2024). Defining Disadvantaged Places: Social Burdens of Wildfire Exposure in the Eastern United States, 2000–2020. Fire, 7(4), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7040124. Workshop presentation by Susan Cutter June 14, 2024 (slide 8).

smoke, can have transboundary and long-term effects (see Sarah Henderson’s presentation and discussion in Chapter 6 for additional information on this point).9

Challenge 3: Know Antecedent Conditions and Local Changes

Cutter suggested a third challenge, tied to understanding the antecedent conditions and local changes before an event occurs, involves identifying the root causes of events. As examples, she mentioned how ecosystem change and modification may have contributed to the Maui Fire in Hawai’i, just as the conversion of grasslands into housing developments could have increased fire risk in the Marshall Fire near Broomfield, Colorado.10 Though it is crucial to recognize how land conversion and demographic shifts elevate risk, she noted that anticipating and understanding these conditions beforehand is increasingly challenging.

Challenge 4: Prepare for Recovery

The final challenge Cutter discussed relates to the recovery process—and the necessity of preparing for it. Recovery does not simply happen on its own, she observed; it requires a well-prepared plan to ensure it occurs swiftly, effectively, and equitably. In Los Angeles, California, efforts led by the Dr. Lucy Jones Center11 focusing on addressing recovery challenges have prompted Cutter’s involvement in studying the Camp and Dixie fires.

___________________

9 See also Dong, M., Malsky, B., Gamio, L., Bloch, M., Reinhard, S., Abraham, L., González Gómez, M., Jones, J., Murphy, J.-M., & Hernandez, M. (2024, June 27). Maps: Tracking air quality and smoke from wildfires. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/us/smoke-maps-canada-fires.html

10 More information on the Marshall Fire is available at https://research.noaa.gov/2024/01/08/lookingback-at-coloradosmarshall-fire/

11 More information about Dr. Lucy Jones Center is available at https://drlucyjonescenter.org/ and resources for steps towards resilience and strengthening communities is available at https://drlucyjonescenter.org/resources/#from-recovery-to-resilience-report

Obstacles and Lessons Learned

In communities affected by wildfires, Cutter has observed not only numerous obstacles but also many lessons being learned. One significant lesson is the disparity in recovery between rural frontier areas like Greenville and communities within the Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI). WUI communities, she has observed, typically have better access to resources and quicker service restoration due to their proximity to assistance. Conversely, rural frontier area recovery efforts are hindered, she suggested, by slow service restoration, limited broadband access, and delayed post office operations. This situation can be exacerbated when basic services required for accessing FEMA relief, such as online applications, are inaccessible due to limited internet connectivity.

Another aspect Cutter highlighted in her discussion of recovery efforts was the importance of building relationships before a disaster strikes. Establishing connections with emergency managers and community members beforehand could result in a smoother response and better recovery phase. She suggested that, rather than introducing oneself during a crisis, it is essential to have established pre-existing networks and familiarity with individuals.

Another lesson Cutter pointed to is the complexity and difficulty of navigating government programs, which can both severely stretch the capacity of local communities and slow down their recovery efforts. Having to navigate this complexity can make it challenging for communities to recover and stay united since residents may not be able to afford to wait years to return to their homes. Additionally, she observed, there is a shortage of disaster case management personnel. These professionals can play a critical role in assisting people to navigate the federal and state resources available for home reconstruction; however, Cutter noted that the bureaucratic hurdles and red tape people may be forced to navigate are extremely daunting and can re-traumatize community members struggling with the aftermath of a wildfire. She observed that this double trauma—first from the fire itself, and then second from the recovery process—underscores the significant challenges faced by these communities.

The next lesson Cutter emphasized was the importance of community proactivity in disaster response and recovery. Agencies such as FEMA only assist when requested by governors and local communities; they do not initiate help. Therefore, communities must actively seek out resources, Cutter emphasized; they may not be able to afford to passively wait for assistance.

RESEARCH NEEDS

Gaps in Understanding

Going on to discuss gaps in understanding, Cutter noted that rurality remains a key underlying correlated driver of some of the consequences. Many disparities in technology access exist among rural households. This disparity in access may affect the ability of some individuals to register for FEMA aid and could influence recovery timelines, which vary significantly across different locations and communities.

In Paradise, recovery may have been hindered by persistent environmental toxins that delayed reconstruction efforts due to safety concerns. She also suggested that households, while seeking assistance, faced challenges with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Cutter observed that some residents rebuild in order to return to some level of normalcy—or, alternatively, build larger homes to increase property values. The evolving nature of communities post-disaster could be a significant concern, with both proximal and distal impacts becoming increasingly evident in the future. Vulnerability and resilience among populations will undergo dynamic changes, she said, which could potentially lead to the emergence of new vulnerable groups—that is, previously unrecognized individuals now living on the brink of vulnerability. She commented that a unique challenge exists in eastern regions where heirs to property can pass ownership down without presenting any formal documentation, complicating the process of accessing federal resources and homeowner assistance.

Cutter has also observed the growing trend of individuals in rural areas who opt to live off the grid. Choosing to live independently as they do, away from conventional infrastructure like sewers and power grids, these people’s lifestyle makes them vulnerable in new ways. Additionally, transient populations and undocumented individuals also face unique vulnerabilities. Cutter emphasized that ongoing challenges remain, including the

need to address antecedent conditions of social demographic and environmental changes; accurately measuring losses; and assessing damages.

Lastly, Cutter noted that with regard to risk information, there is a significant challenge when it comes to understanding, communicating, and building trust. One factor hampering the acceptance of information provided to communities could be a certain widespread distrust in government, science, and other institutions. Overcoming this lack of trust is crucial in the ongoing effort to encourage communities to take protective actions in the face of risks such as wildfires. Addressing this issue could be a major concern moving forward.

Needs for Research and Policy

In terms of research and policy needs, Cutter observed that there are several critical areas to address. First, there is a call for a national hazard insurance policy that transcends specific hazards such as floods, earthquakes, and wildfires. Particularly needed in rural areas lacking adequate insurance options, such a policy could provide consistent coverage and support regardless of the disaster type.

Another urgent need Cutter described was the development of a comprehensive local recovery guide for rural communities. Such a guide, designed to streamline and expedite recovery processes, could outline clear steps, specify whom to approach—state, county, or federal agencies—and when to seek assistance. Currently there is a gap in national legislation guiding long-term recovery after disasters, she noted. While the Stafford Act12 covers preparedness, response, and mitigation, FEMA’s role ends after six months, leaving long-term recovery to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) through their Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program.13 However, guidance on this program is only published in the Federal Register post-event, which Cutter believes highlights the need for formalized roles and clearer processes.

Cutter suggested that improvements in documenting losses and processes may be essential for consistency and effectiveness across disaster response and recovery efforts. She said there could also be a critical need, among both individuals and communities, for consistent assessment of differential preparedness, response, and recovery capabilities, which could be used to better allocate resources where they are most needed.

This results in “changing livelihoods and livability of places,” Cutter said, noting that people’s attachment to where they live is called topophilia—the love of place. Cutter noted that with respect to uncertainty regarding environmental changes and disasters, the emotional and psychological impacts can be significant. Many communities may experience distress and solastalgia, a sense of loss due to environmental degradation. Coming to terms with this emotional toll by acknowledging and working to preserve people’s deep connections to their sense of place may help us learn to do a better job of underscoring the importance of planning for resilience. In closing, Cutter said she has observed that while planning for the worst-case scenarios is essential, there is also the need to “hope for the best.”

Exploring the Possibility of an All-Peril National Catastrophic Insurance Program

Michael Wara noted how he is intrigued by Cutter’s proposal for an all-peril national catastrophic insurance program, especially given the challenges often associated with the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).14 He asked her to elaborate on her vision for such a program.

Cutter responded by saying the proposed all-peril national catastrophic insurance program would be structured on actuarial principles, with the federal government acting as the primary underwriter. In the United States, there have been discussions about catastrophe bonds and other financial instruments, Cutter noted, but relying solely on private-sector insurance might not be feasible due to varying levels of homeowner policy coverage. She suggested that the goal would be to establish a safety net ensuring that people can maintain a minimum standard of living in the event of a disaster.

___________________

12 More information about WUI is available at https://www.fema.gov/disaster/stafford-act

13 More information about HUD’s CDBG program is available at https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/comm_planning/cdbg

14 More information about NFIP is available at https://www.floodsmart.gov/

Addressing the Need for Standardized Federal and State Support in Fire-Prone Areas

Currently, FEMA oversees the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which includes funding and processes for managed retreat from flood-prone areas. However, at this time, there is not one clear institution responsible for managing retreat from wildfire-prone areas—which is presently not practiced in a substantial way but could be adopted in the future.15 A virtual audience member noted that, while communities should be leading discussions on retreat, there may be, in this context, a need for policy recommendations to standardize federal and state support. The participant asked what specific policies at both federal and state levels could ensure consistent and effective support for managed retreat?

Cutter responded that the NFIP program faces significant challenges, which may be evident from the absence of substantial federal reform given the program’s frequent extensions under continuing resolutions. The problem could lie in the fact that most federal disaster programs, including NFIP, being tailored to specific perils such as floods, have lacked any dedicated programs for wildfires—or, historically, even for hurricanes, until recently. In this context, Cutter suggested that focusing on state-level initiatives could be more practical. Since every state contends with wildfire challenges—although the extent can vary across regions—she suggested addressing these issues may necessitate a state-centric approach to effectively manage wildfire risks.

Overlaying Community Emergency Response Team Effectiveness and Insurance Coverage on Vulnerability Maps

Jonathan Fink, committee chair, raised a question regarding the possibility of overlaying the effectiveness of Community Emergency Response Teams (CERT)16 on maps showing vulnerability across the United States. He noted that while there are approximately 2,600 communities with CERT teams, their effectiveness varies significantly. Cutter responded by acknowledging that the presence or absence of is one of the input variables in the resilience index. She mentioned that this resilience index, along with a variant of the social vulnerability index, is part of FEMA’s National Risk Map.17

Fink responded by asking whether areas around the country where people have lost homeowner coverage from major insurance companies could also be incorporated into these indices? Cutter explained that while this data does not currently appear as part of the index, as long as the input data is available and accessible, it is possible to map such information.

Addressing the Vulnerabilities of Renters in Disaster Planning and Recovery

Noting that the presentation primarily focused on homeowners, an audience member inquired about the vulnerabilities of renters. He asked if there was existing research on renters—or, if not, how research needs for this demographic could be identified?

Cutter responded by saying the focus in most discussions revolves around homeowners because they can access more relief resources from FEMA and other federal agencies. However, renters, who are inherently a vulnerable population nationwide, represent a significant concern. For instance, renters in coastal areas can face displacement when the owners of buildings decide, after disasters, to construct condominiums, reducing rental housing stock and driving up rental prices. She highlighted the need, in disaster planning and recovery efforts, to address renters’ unique challenges and vulnerabilities since it is frequently the case that they are the most impacted demographic in many disaster scenarios.18

___________________

15 McConnell, K., & Koslov, L. (2024). Critically assessing the idea of wildfire managed retreat. Environmental Research Letters, 19(4), 041005.

16 More information about FEMA’s CERTs is available here: https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/individuals-communities/preparedness-activities-webinars/community-emergency-response-team

17 More information about FEMA’s National Risk Map is available here: https://www.fema.gov/flood-maps/tools-resources/risk-map

18 Lee, J. Y., & Zandt, S. V. (2018). Housing tenure and social vulnerability to disasters: A review of the evidence. Journal of Planning Literature, 34(2), 156–170.

Incorporating Health Data into Resilience Indices

A workshop participant asked if data on the number of recipients of Medicare or Medicaid could be integrated into the resilience indices. Cutter responded that there is no consistent, readily available data on those who receive Medicare and Medicaid that can be included directly into the indices. However, for certain areas, it is possible to obtain this information and incorporate it into the computations. She went on to note that such data is often correlated with factors like age and income levels, leading to potential issues of collinearity within the index.

NAVIGATING COMPLEXITIES IN DISASTER RECOVERY

Karl Kim noted that managing and implementing recovery efforts at a national, state, or even large municipal level is exceptionally difficult. A dilemma he has observed concerns how, rather than following external guidelines and procedures, often people’s desire to return to normalcy triggers the usual planning, development, and rebuilding processes. Another challenge is the role of HUD as a major national entity—although the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program was not originally designed for disaster response since its rules and conditions differ significantly from those needed for disaster recovery. This dilemma leaves him torn between, on the one hand, the idea of bolstering local capacity to manage recovery independently—and, on the other, the necessity for external resources and assistance. He said that considering the vast size of our country, finding a one-size-fits-all solution for these issues is incredibly challenging.

Cutter agreed that recovery must be locally driven but emphasized the need for consistent support across different disasters. Understanding how to effectively implement long-term recovery efforts remains a significant challenge.

Kim’s experience with various recovery efforts leads him to believe that managing expectations is crucial. Many people anticipate that FEMA or HUD will rebuild everything, yet personal savings, supplemented by insurance coverage where applicable, typically serve as the primary resource for recovery. This reliance on outside help often results in delays as individuals wait for others to take action. Addressing these challenges, Kim emphasized, requires a steadfast focus on providing reliable disaster recovery support.

Cutter noted that due to these dynamics, significant inequalities, impacting environmental justice outcomes, emerge during the recovery process. Since communities often consist of diverse groups with varying abilities to recover, recovery efforts, viewed through an environmental justice lens, must consider “recovery for whom?” Some segments of a community may rebound quickly, while others may struggle or even fail to recover entirely. Determining whether to prioritize rapid rebuilding or sustainable development poses difficult challenges. These discussions can exclude certain voices from decision-making and the recovery process itself, highlighting not only the complexity in this area but also the need for further exploration and solutions.

Strategies and Challenges to Manage Wildfire Risks

An audience member noted that wildfires present a unique hazard because, unlike geological phenomena such as plate tectonics, we can influence and modify factors contributing to fire risks. Methods can range from small-scale actions, like creating defensible spaces around homes, to larger strategies, such as establishing buffer zones and comprehensive landscape management. Given the scale of the issue—as of 2020 approximately 32 percent of homes in the United States are situated in the WUI19—he asked whether managed retreat from high-risk areas should be considered, or if we should concentrate more on improving fuel management strategies? These considerations raise important questions about the most effective ways to mitigate wildfire risks and protect communities in the long term.

___________________

19 Phillips, J. (2023, November 20). Between nature and neighborhoods: Mapping the dynamics of wildland-urban interface and growing wildfire threats. U.S. Forest Service. https://research.fs.usda.gov/news/featured/between-nature-and-neighborhoods-mapping-dynamics-wildland-urban-interface-and

Cutter responded by saying that’s “opening up a little Pandora’s box. In some places, you may get one answer, and in another place, you’ll get a very different answer.” Ultimately, she said, it’s about understanding why people choose to live, or are forced to live, in hazardous places.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Jonathan Fink, Committee Chair and Professor at Portland State University

Fink noted that earlier workshop discussions emphasized the importance of geographic context, distinguishing between site (place) and situation (context). All places have unique vulnerabilities and resilience capacities, as Cutter discussed. Addressing these differences involves tracking both proximal and distal impacts. An issue identified by Cutter is the lack of trust, which affects the uptake of emergency information.

Fink reflected on the key research needs that Cutter mentioned. Among others, he highlighted the need for research on these matters: a national hazard insurance policy; a local recovery guide for rural communities; federal legislation for recovery; improved documentation of losses; and the vulnerability of renters.

This page intentionally left blank.