Social-Ecological Consequences of Future Wildfires and Smoke in the West: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 4 The Range and Scope of Social-Ecological Consequences of Wildfire in the West

4

The Range and Scope of Social-Ecological Consequences of Wildfire in the West

This session delved into the wide-ranging social and ecological impacts of wildfires, the aim being to illuminate the diverse consequences these events have on various communities. The session moderator, Alexandra Paige Fischer, committee member and associate professor at the University of Michigan, explained that the discussion would be structured to gain an understanding of how different community types—rural, overburdened, and marginalized, at different geographical scales, and with varying levels of healthcare, co-morbidity, and resources—experience and manage wildfire threats. Panelists discussed different types of community vulnerability or exposure to wildfire risk; differing levels of sensitivity to the effects of wildfire risk as a function of resource availability and other stressors; and differing adaptive capacities. The panelists were asked to consider questions such as the following: How have communities you have studied been affected by wildfires? In these relevant cases, what were the key vulnerabilities? In your view, how can communities, going forward, best reduce adverse impacts from wildfires? What do you believe should be the focus of future wildfire sciences?

URBANISM + FIRE: RESISTANCE, CO-CREATION AND RETREAT IN THE PYROCENE

Emily Schlickman, Assistant Professor at the University of California at Davis

Schlickman emphasized that in the American West fire has always been part of the landscape, but the last two decades have seen catastrophic events. She described an image from August 2020 where a complex fire 10 miles away resulted in localized ash-covered surfaces and an orange sky, illustrating how not just rural but also urban areas are impacted by wildfire-related air pollution. Highlighting the direct impacts of wildfires on urban areas, using as an example Coffey Park within the city limits of Santa Rosa, California, Schlickman explained that in 2017, the Tubbs Fire crossed six lanes of highway and destroyed approximately 1,000 homes. Though nearly every home has since been rebuilt, the community has neither significantly altered its building footprints or vegetation, nor has it used fire-resistant building materials to anticipate and prepare in advance for future fires. With this example, she emphasized two points: first, Coffey Park is not within a designated fire hazard severity zone, so there are no requirements for it to anticipate or prepare for fire; and second, Coffey Park’s experience and situation is not an anomaly.

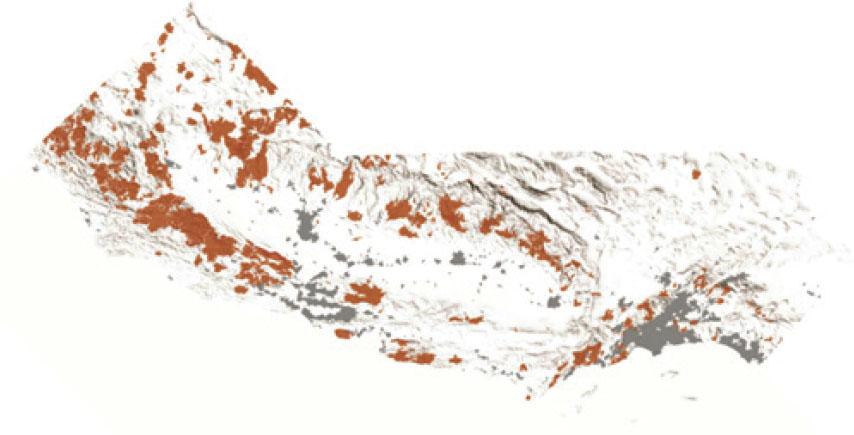

Showing a map of California highlighting the overlap between urban areas and wildfire perimeters (see Figure 4-1), Schlickman noted that urban development is often considered a primary driver of wildfire events. She said the

NOTE: Gray denotes urban areas as defined by the U.S. Census, orange denotes wildfire perimeters in the last 10 years.

SOURCE: Map created by presenter, Schlickman; data for urban areas are from the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans); fire perimeter data is stewarded by CAL FIRE - FRAP, with data from CAL FIRE (including contract counties), USDA Forest Service Region 5, USDI Bureau of Land Management & National Park Service, and other agencies.

encroachment of development into wildlands increases the potential for ignition, and that climate change, bringing hotter and drier conditions, increases wildfire risk and contributes to large-scale landscape shifts. She went on to talk about the impact of colonization, which has altered fire regimes and landscape management practices over the last 150 years, often making landscapes more vulnerable to wildfires.

Recent wildfire events have uniquely affected urban areas due to the high density of critical infrastructure, which Schlickman explained can disrupt regional resources like water and electricity. Urban areas also have a higher density of business and residential structures, which can lead to larger material losses and potentially turn wildfires into urban fires, in which houses and other structures act as fuel, making suppression more difficult. Many urban residents may have a false sense of security, she said, because they assume wildfires cannot reach them since their areas are not designated fire hazard severity zones.

Furthermore, wildfires impact different populations in different ways, she pointed out, creating environmental justice issues. Urban residents without well-sealed homes or air purifiers are more affected by wildfire smoke. Differences in people’s ability to prepare, evacuate, and rebuild also create disparities. For example, peri-urban areas at the edges of cities, where living costs are lower but fire risk is higher, often support diverse populations with varying capacities to prepare for wildfires. Some residents cannot easily evacuate due to mobility issues or fire messaging-related language barriers. Additionally, many are uninsured or underinsured, making it difficult for them to rebuild after a wildfire.

For the past five years, Schlickman and her colleague Brett Milligan have reviewed design and planning techniques implemented globally in fire-prone areas.1 They identified 27 spatial strategies grouped into three technique-related categories, each intended to embrace and utilize landscape forces and strategies to intentionally minimize the need for human intervention:

- Resist: This is a category of techniques that resist the creative and transformative power of fire and the forces of landscape change. For example, in Mission Viejo, an urbanized area southeast of Los Angeles where development is still occurring, people in a particular community are rethinking development layouts

___________________

1 Schlickman, E., & Milligan, B. (2023). Design by fire: Resistance, co-creation and retreat in the Pyrocene. Taylor & Francis.

- Co-Create: This designates techniques that embrace and utilize landscape forces while also trying to co-create with them. Around Clear Lake, communities, in collaboration with Indigenous-led fire crews, are adopting beneficial burns, thus reducing wildfire risk while promoting ecological and cultural co-benefits. For example, a burn in an oak savannah created habitat mosaics, reduced fuel, and managed weevils for an upcoming acorn harvest.

- Retreat: This designates techniques that intentionally retreat from and minimize human intervention in landscapes remade by human agency. Areas affected by the 2018 Camp Fire are implementing wildfire risk reduction buffers. The city of Paradise is purchasing properties at the town’s edge where rebuilding is not occurring.2 Adjacent to Paradise, to provide safer living locations, the community of Chico is focusing on infill opportunities for higher-density, mixed-use developments near the urban core.

in order to mitigate wildfire risk by implementing a “donut”-like design approach, with houses there being clustered together and both a wide road and irrigated crops ringing the community to create a fire break and staging area for suppression efforts.

Schlickman concluded by emphasizing the importance of future fire and climate research focused on helping communities adapt to the new normal. She stressed the need for policies that support these adaptive approaches.

Effective Land Use Strategies and Future Opportunities

With regard to which land use strategies are most effective for high-wind and ember- spread events, Schlickman said that limiting development in very-high-severity zones is likely the most effective tool. When Fischer inquired about opportunities to impact community resilience using the built environment looking ahead to the next five to ten years, Schlickman suggested focusing on infill development within existing cities. She suggested that what could significantly enhance community resilience to wildfires would be directing resources, time, and policies toward building up downtown areas, rather than expanding into peripheral wildlands.

COMMUNITY VULNERABILITY AND RECOVERY FROM WILDFIRES

Miranda Mockrin, Research Scientist, U.S.D.A. Forest Service

Mockrin shared research that considers the consequences of wildfire for different communities. She began by highlighting the significance of the aging population in the United States, particularly members of the Baby Boom generation, who throughout their lifetime have been more likely to move into exurban or rural areas, coinciding with the growth of the wildland-urban interface.3 She noted that older individuals are often more vulnerable during wildfires due to various factors, including personal health conditions, housing quality, and communication challenges—as well as mobility issues during evacuations.4

Mockrin presented recent research on population age and wildfire risk, conducted in collaboration with Dr. Richelle Winkler at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, drawing from the decennial census and a dataset of wildfire risk from the U.S. Forest Service. The research shows that in higher wildfire risk areas, the percentage of residents over age 60 increased from 2010 to 2020, going from 7 percent to 9.8 percent of the total population; often this increase is due to people who had been living in these higher risk places for years

___________________

2 Schlickman noted the low level of participation, with only 2% of needed properties acquired. She emphasized that while buffers can help slow down fires, they cannot stop them, and the scale of implementation is massive.

3 Radeloff, V. C., Mockrin, M. H., Helmers, D., Carlson, A., Hawbaker, T. J., Martinuzzi, S., Schug, F., Alexandre, P. M., Kramer, H. A., & Pidgeon, A. M. (2023). Rising wildfire risk to houses in the United States, especially in grasslands and shrublands. Science, 382(6671), 702–707.

4 Garner, J. M., Iwasko, W. C., Jewel, T. D., Charboneau, B. R., Dodd, A. A., & Zontos, K. M. (2020). A multihazard assessment of age-related weather vulnerabilities. Weather, Climate, and Society, 12(3), 367–386; Melton, C. C., De Fries, C. M., Smith, R. M., & Mason, L. R. (2023). Wildfires and older adults: a scoping review of impacts, risks, and interventions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6252.

and, growing older, have not left.5 People are also the oldest in areas with the highest risk.6 In 2020, people were over age 60 made up 23 percent of those living in the lowest-risk census blocks, but 32 percent of those in the highest-risk census blocks. The geographical distribution at the state level shows a substantial number of people over age 60 living in moderate to high wildfire risk areas, across the United States. Notably, this is not exclusive to places such as California and Arizona, but is also evident in the Great Plains, the Southeast, and some locations not typically thought of as representing a high fire risk—but which are in fact fire-prone—such as Hawaii, Arkansas, and Missouri.

This trend is concerning, Mockrin said, given not only the substantial number of people living in places at high fire risk but also the unfortunate losses that have already been seen among older people in wildfire events. For example, the average age of those who died in the 2023 Maui fire was 65 (p. 53).7 In the 2018 Camp Fire, the average age was 72, and for the fires that burned across Sonoma and Napa in 2017, the average age was 73.8 Given how fire activity is expected to increase in the future—alongside the fact that 20.6 percent of the U.S. population will be over age 65 by 20309—she emphasized that it is crucial to further invest in mitigation and preparedness, especially for this demographic. Mockrin went on to note that taking into consideration class and economic positionality is critical when determining the capacity for mitigation and post-fire recovery. She noted that available resources significantly impact how individuals and communities experience and manage fire. She acknowledged however that it can be challenging to capture household income and other economic data at the same detailed level as age data (that is, by census block).

Shifting to the research documenting wildfire building losses and recovery, Mockrin’s general takeaway was that the recovery process after wildfires is lengthy and complex.10 Challenges grow and intensify in rural and exurban areas, she said, compared to more urban or suburban areas. She highlighted research on recovery trajectories for two different fires that took place in 2009, each burning approximately 60 homes in a planned urban development: one in North Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, and the second in exurban Los Angeles County.11 In South Carolina, the number of rebuilt homes rapidly increased, and within a few years their rebuilding was largely complete—while the inverse pattern was seen in Los Angeles County where there was very limited rebuilding during the first four years after the fire.

Interviews with local government and community leaders indicate that, compared with urban and suburban areas, rural and ex-urban settings present several unique factors and logistical concerns.12 These factors include the increased time needed to rebuild, higher rebuilding costs, the complexity of rebuilding (e.g., based on being farther away from contractors and building supplies), and inadequate insurance payouts. Additional challenges

___________________

5 Winkler, R. L., & Mockrin, M. (2024, February 8). Aging and wildfire risk in the USA [Virtual conference session]. Presentation to the Applied Demography Conference.

6 Based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Demographic and Housing Characteristics File (DHC) and and Scott, J. H., Dillon, G. K., Jaffe, M. R., Vogler, K. C., Olszewski, J. H., Callahan, M. N., Karau, E. C., Lazarz, M. T., Short, K. C., Riley, K. L., Finney, M. A., & Grenfell, I. C. (2024). Wildfire risk to communities: Spatial datasets of landscape-wide wildfire risk components for the United States (2nd ed.). Forest Service Research Data Archive.

7 Maui Police Department (2024, January). Maui strong: Maui wildfires of August 8, 2023, Maui Police Department preliminary after-action report. https://www.mauipolice.com/uploads/1/3/1/2/131209824/pre_aar_master_copy_final_draft_1.23.24.pdf

8 Bénichou, L., Peterson, N., & Pickoff-White, L. (2020, August 10). How we analyzed where older Californians are at increased risk for wildfire. CalMatters. https://calmatters.org/projects/older-californians-increased-risk-wildfires/

9 U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). 2023 national population projections tables: Main series. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2023/demo/popproj/2023-summary-tables.html

10 Recovery studies on building and rebuilding after fire, are national Mockrin, M. H., Fishler, H. K., Kramer, H. A., Radeloff, V. C., & Stewart, S. I. (2022). A tale of two fires: retreat and rebound a decade after wildfires in California and South Carolina. Society & Natural Resources, 35(8), 875–895.

11 Mockrin, M. H., Fishler, H. K., Kramer, H. A., Radeloff, V. C., & Stewart, S. I. (2022). A tale of two fires: retreat and rebound a decade after wildfires in California and South Carolina. Society & Natural Resources, 35(8), 875–895.

12 Mockrin, M. H., Stewart, S. I., Radeloff, V. C., & Hammer, R. B. (2016). Recovery and adaptation after wildfire on the Colorado Front Range (2010–12). International Journal of Wildland Fire, 25, 1144; Mockrin, M. H., Fishler, H. K., Kramer, H. A., Radeloff, V. C., & Stewart, S. I. (2022). A tale of two fires: retreat and rebound a decade after wildfires in California and South Carolina. Society & Natural Resources, 35(8), 875–895; Mockrin, M. H., Fishler, H. K., & Stewart, S. I. (2018). Does wildfire open a policy window? Local government and community adaptation after fire in the United States. Environmental Management, 62, 210–228.

in rural areas can include vegetation restoration; a variety of other hazards (e.g., mudflows); infrastructure repair (e.g., private roads and septic systems); and how government and civic resources may not be as robust in their response as they are in more urban or developed areas. Mockrin emphasized the importance of, and need for, more research to understand not only the role of place attachment in different settings but also the lived experiences of individuals navigating these recovery processes.

Looking ahead, Mockrin identified several research needs. She stressed the importance of tracking wildfire effects on communities through consistent data collection on losses. Currently, only California collects spatial data on buildings lost, through the state’s Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE). She called for more research on the long-term recovery and lived experiences of affected individuals in order better to understand the chronic nature of wildfire hazards and their long-term effects on communities.

ADDRESSING RURAL ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE IN THE CONTEXT OF WILDFIRE RISK

Beth Rose Middleton Manning, Professor at the University of California, Davis

Bringing a rural environmental justice lens to the discussion of wildfire risk, Middleton Manning characterized rural areas on the basis of the following categories: low population density; land use (i.e., resource stewardship or extraction); and land cover (e.g., vegetation, open space, amount of development).13 While in some rural areas in California the population will be predominantly white, in other rural locations it will include people who are African American, Latino/Latinx, or non-federally-recognized Native American/Indigenous tribal members. There are also “hidden” diverse populations, such as undocumented individuals and transient workforces, who do not live in the community all the time—but that at the same time may be affected by wildfires.

Middleton Manning highlighted the overlap between low-income communities and forested areas. Some forested-area-residing disadvantaged communities—containing people who may also be facing impacts of pollution14—can be overlooked in measurements like those conducted by CalEnviroScreen.15

Next, providing definitions relevant to the consideration of environmental justice, Middleton Manning discussed the following terms:

- Environmental justice refers to the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, in the context of the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.16

- Rural environmental justice involves paying special attention to not only the impacts and scope of pollution in less populated areas, but also the understudied exposure pathways that impact rural populations reliant on local resources. Rural environmental justice addresses the consequences of persistent disinvestment. She pointed out that rural regions often serve urban areas as sources of water, power, timber, and minerals, but do not receive adequate reinvestment once the boom-and-bust economy cycles are completed.

- Indigenous environmental justice is specifically attentive to settler colonial structures, institutions, processes, and practices as constitutive of persistent environmental injustice; culturally specific exposure pathways and impacts of contamination; and the disruption of traditional stewardship practices.

___________________

13 To view the rural, suburban, and urban census tracks, see Paykin, S., Menghaney, M., Lin, Q., & Kolak, M. (2021). Rural, suburban, urban classification for small area analysis. Healthy Regions & Policies Lab, Center for Spatial Data Science, University of Chicago.

14 Martinez, D. J., Middleton, B. R., & Battles, J. J. (2023). Environmental justice in forest management decision-making: Challenges and opportunities in California. Society & Natural Resources, 36(12), 1617–1641.

15 More information about CalEnviroScreen is available at https://oehha.ca.gov/calenviroscreen

16 Federal Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice & NEPA Committee. (2016). Promising Practices for EJ methodologies in NEPA reviews. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-08/documents/nepa_promising_practices_document_2016.pdf

Some populations, Middleton Manning observed, are more significantly affected by wildfire (i.e., rural distributive injustice) and have a limited or reduced ability when it comes to influencing policy decisions aimed at preventing megafires (i.e., rural procedural injustice). As an example, she cited the Dixie Fire, which came through Greenville Mountain in California in 2021. A Maidu elder remarked that traditional forest stewardship, if it had been allowed to continue, could have prevented the conditions that led to the Dixie Fire. Despite mandates for environmental justice, when it comes to fire risk reduction planning,17 there is limited focus on rural areas.

Middleton Manning defined “vulnerability” as referring to both the likelihood of a hazard occurring as well as the factors that may reduce a community’s ability to prepare for, withstand, and recover from a catastrophic fire. Possible individual factors include income; savings; home insurance; medical insurance; demographics such as age; social networks; and housing age, value, and status (renter vs. owner). Defining rural vulnerabilities and the needed assets can help build adaptive capacity, which is the ability to prepare for, withstand, and recover from catastrophic fire. An asset-based approach—which begins with community strengths and may include knowledge of the local ecosystem, familiarity with escape routes, strong social networks, high capacity for mutual aid, and community-based support structures—should be used, she said.

She discussed using community assets and strengths, with embedded systems of adaptive capacity and resilience, to support rebuilding fire-hardened communities. Adaptive capacity can be built through cultural fire practices, community planning tools, and the leveraging of local expertise in forestry and emergency services. She emphasized that inclusive planning that recognizes the skills and knowledge of Indigenous and long-term residents is crucial.

Instrumental in understanding adaptive capacity is the “capitals framework.” This framework is based on a community’s capacity to “respond to external and internal stresses; to create and take advantage of opportunities; and to meet the needs of residents, diversely defined.”18 The capitals are divided into six areas: existing physical capital (e.g., infrastructure); financial capital; natural ecological capital; human capital (e.g., skills training, experience); cultural capital (beliefs, norms, relationships, responsibility, and commitments); and social capital (the ability to work together). Middleton Manning posed the following questions: How can these capitals, viewed individually and collectively, build resilience to the increasing catastrophic wildfire risks? After a fire, how are these capitals impacted? What remains, and how can existing capitals be utilized to respond to future risks?

A critical aspect of the “capitals framework,” she noted, is inclusivity: In other words, who is involved in the planning process? Often, community leaders present their views on what they see as capitals, but she stressed that it is essential to include the appropriate urban or rural hidden and vulnerable populations. She highlighted the need, even in sparsely populated areas, for inclusive planning models that address varying fire risk experiences.

With regard to planning for fire risk, an asset-based approach leverages community strengths. Middleton Manning emphasized how in many rural western communities that have a timber economy heritage, there is a need to engage the local people skilled in forestry with local educational institutions to capitalize on their expertise, while at the same time providing them training in restoration forestry, carbon sequestration, and land stewardship. She suggested that what should be central in wildfire adaptation, education, and planning is collaboration with agencies and firms to ensure the availability of jobs for newly trained community members, building on mutual aid traditions and place-based cultural and agricultural knowledge. She highlighted as an example how the Sierra Institute19 repurposed an abandoned mill site. The nonprofit cleaned up contamination and employed locals in the utilization of local forest materials in order to rebuild and enhance forest resilience.

To summarize, Middleton Manning discussed addressing rural environmental justice by shifting toward an emphasis on adaptive capacity and away from vulnerability. This involves identifying community assets and activating them to bolster adaptability and resilience against predicted future fires. It also requires identifying necessary supports to build those assets, which may include policy, workforce development, and strategic invest-

___________________

17 Adams, M. D., & Charnley, S. (2018). Environmental justice and US Forest Service hazardous fuels reduction: A spatial method for impact assessment of federal resource management actions. Applied Geography, 90, 257–271.

18 Kusel, J. (2001). Assessing well-being in forest dependent communities. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 13(1–2), 359–384; Middleton, B. R., & Kusel, J. (2007). Northwest economic adjustment initiative assessment: Lessons learned for American Indian community and economic development. Economic Development Quarterly, 21(2), 165–178.

19 More information about the Sierra Institute is available at https://sierrainstitute.us/

ments in organizations or Indigenous-led efforts. An inclusive process is vital to identifying and supporting diverse projects to prepare for predicted fire impacts and determine which projects to fund. She referenced the work involved in developing a qualitative rubric for project funding.20 This rubric would emphasize diverse partnerships, acknowledge community diversity, include conflict resolution, and commit to long-term forest stewardship with local workforce development. It also stresses tribal leadership and traditional ecological knowledge, recognizing long-term Indigenous environmental justice. Middleton Manning closed by explaining that this is a more qualitative approach—proceeding one person, one project, and one community at a time—to build adaptive capacity to address fire risk.

CHALLENGES AND HISTORICAL CONTEXTS OF CULTURAL BURNING: INSIGHTS ON MANAGING WILDFIRE RISKS TODAY

A workshop participant stated that prehistoric Indigenous communities likely faced similar weather constraints to those we face today and may have focused on high-priority areas near their communities. This participant asked the following question: Realistically speaking, how much land could these communities have managed using traditional methods, given that today’s efforts fall short of the acreage some believe should be treated despite having a larger population?

Schlickman responded by noting that before colonization occurred, the number of acres burned annually varied, with estimates suggesting up to approximately 4.5 million acres per year in California, including both cultural burns and lightning-ignited fires.21 She highlighted the challenges of scaling up cultural burns today, despite strides made in reducing liability and permitting hurdles in states like California. She emphasized that it is not just about the quantity of acres burned but also the quality, the aim in these instances being to create a mosaic pattern that supports culturally significant and beneficial habitats and species. Noting that cultural and prescribed burning cannot be applied everywhere, she acknowledged the complexities involved, saying that targets are not currently being met, which creates challenges for scaling up.

Historically speaking, Middleton Manning observed, Indigenous people devoted extensive care to their homelands, a practice disrupted by colonial invasion and fire suppression. In further remarks, she first noted that while stewardship did continue, its scale was reduced—and then added that in order to reintroduce it on a broader scale today, significant work would be needed to prepare and manage fuel conditions.22

REBUILDING WATER SYSTEMS AFTER WILDFIRES: CHALLENGES AND INNOVATIONS

A workshop participant asked about redesigning water systems in neighborhoods after a fire is over. Schlickman acknowledged that rebuilding water systems can be a significant challenge. After the Camp Fire, for example, the town of Paradise had undrinkable, toxic water, and it took a long time to rebuild the infrastructure. Though some rebuilt communities have considered creating refuge locations near water bodies that could also be a spot for helicopters to get access to water, Schlickman emphasized this is an area that needs further research. Mockrin noted that fires have prompted consideration being given to the upgrading of septic infrastructure in order to prevent contamination of critical water resources. This, she noted, is an example of an attempt to address multiple environmental hazards or goals. Referencing other aspects of rural environmental justice, Middleton Manning

___________________

20 Martinez, D. J., Middleton, B. R., & Battles, J. J. (2023). Environmental justice in forest management decision-making: Challenges and opportunities in California. Society & Natural Resources, 36(12), 1617–1641.

21 Stephens, S. L., Martin, R. E., & Clinton, N. E. (2007). Prehistoric fire area and emissions from California’s forests, woodlands, shrublands, and grasslands. Forest Ecology and Management, 251(3), 205–216.

22 There is research underway such as the following examples which were provided: Eisenberg, C., Prichard, S., Nelson, M. P., & Hessburg, P. (2024, March). Braiding Indigenous knowledge and Western science for climate-adapted forests. https://depts.washington.edu/flame/mature_forests/pdfs/BraidingSweetgrassReport.pdf; Greenler, S. M., Lake, F. K., Tripp, W., McCovey, K., Tripp, A., Hillman, L. G., Dunn, C. J., Prichard, S. J., Hessburg, P. F., Harling, W., & Bailey, J. D. 2024. Blending Indigenous and western science: Quantifying cultural burning impacts in Karuk Aboriginal Territory. Ecological Applications, 32(4), e2973.

highlighted the unique challenges associated with rebuilding or restoring functionality to individual wells and dispersed water systems, underscoring the need to also test for contaminants and find mitigation solutions.

EVACUATION CHALLENGES AND HEALTH RISKS OF OLDER POPULATIONS DURING WILDFIRES

Noting the vulnerability of older populations to direct fire effects, a workshop participant asked about not only the increased risk for this age group during evacuations, but also if there could be elevated health and mortality impacts in nearby communities not directly burned? Mockrin acknowledged there is new research being done on the vulnerability of older populations under these conditions. Regarding fast-moving fires, she highlighted the general challenges associated with evacuation, noting that older people might struggle with emergency response systems reliant on cell phones and personal vehicles. She emphasized the importance of reviewing scientific literature and after-action reports to better understand these challenges.

STRENGTHENING THE SOCIAL FABRIC TO INCREASE CLIMATE RESILIENCY: INITIATIVES BEYOND FIRE HAZARDS

Noting that a strong social fabric is important for climate resiliency, a workshop participant asked about initiatives focusing solely on the social fabric, independent of fire or other climate hazards. Middleton Manning responded by mentioning her work on the California Jobs First project.23 This initiative aims to develop sustainable economic strategies in northern California by leveraging community assets and fostering collaboration for job creation in the context of disinvestment and climate pressure. She emphasized that building social fabric is crucial to these efforts. She also referenced rebuilding the Indian Education Center24 as an example of the importance of institutions when it comes to strengthening community bonds. Centers like this can serve as hubs—especially in rural areas with few relevant facilities—for tutoring, community dinners, meetings, and other events.

SHAPING THE FUTURE OF FIRE SCIENCES: RESEARCH STRATEGIES TO MITIGATE WILDFIRE IMPACTS ON COMMUNITIES

Fischer invited comments on how research, in an effort to shape the future of fire sciences, could be used to address and reduce the adverse impacts of wildfires on communities. Middleton Manning suggested three areas where research could be beneficial:

- Ecological studies: Here research could capture the importance of upstream, locally led forest and meadow restoration. Demonstrating the effectiveness of such efforts, including cultural and prescribed fire, could lead to increased investment in these areas, raising water tables and reducing fire risk.

- Policy analysis: Research should support policies aimed at increasing roles and opportunities for local communities to help reduce the threat of catastrophic fire, even on lands outside their jurisdiction, such as public forests and large private land holdings.

- Socioeconomic analyses: Focusing on the economic aspects of local, rural, and tribal communities, research should promote efforts to build on and enhance local skills through specific training that can strengthen rural economies and create more opportunities for wildfire resilience.

Mockrin emphasized the importance of sharing innovative community-level responses to wildfires. She pointed out that research could not only facilitate connections between communities but also share experiences,

___________________

23 More information about California Jobs First is available at https://www.allhomeca.org/california-jobs-first/

24 A list of American Indian Education Centers in California listed by the county in which they are located, is available at https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/ai/re/aidirectory.asp

especially in post-disaster contexts where communities may feel isolated and there are competing priorities and challenges.

In closing, Schlickman highlighted the potential for exploring alternative insurance models, including community-based insurance. She stressed the importance of understanding community perceptions of different wildfire risk management techniques, including tradeoffs such as ecological functions and social and cultural values.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Jonathan Fink, Committee Chair and Professor at Portland State University

This session explored the consequences of different scales of wildfires and their impacts on different populations, focusing on urban, suburban, and rural contexts. Schlickman presented surveyed global strategies for wildfire management and identified a typology of 27 approaches, categorized into resisting, co-creating, and retreating, with examples from California illustrating each category. This framework, Fink said, provides valuable insights for learning from diverse regions, and bringing these perspectives together is crucial.

Mockrin discussed the specific vulnerabilities of different populations, emphasizing the heightened risk for people over age 60. She highlighted the challenges of recovery in impoverished and rural areas and the need for specific data, such as spatial data on lost buildings and recovery dynamics. Fink noted that this theme of missing data recurred throughout the discussions.

Middleton Manning focused on the adaptive capacity of rural populations to address various aspects of environmental justice, which Fink said rounded out the session with an important perspective on community resilience and equity.

This page intentionally left blank.