Blueprint for a National Prevention Infrastructure for Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

The central aim of a national prevention infrastructure1 for mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) disorders is to promote people thriving at all stages of life and across all settings in society. Achieving this calls for concerted effort at all levels of government and in community-based multisector partnerships with the objective of creating and sustaining the conditions for infants, children, adolescents and emerging, working, and older adults to experience MEB health and well-being.

Throughout this report, “MEB disorders” is used to describe disorders diagnosable using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-V) criteria and behaviors associated with them, including violence, aggression, self-injury, suicide, and antisocial behavior. As such, the term “MEB disorders” encompasses mental illness, substance use disorders, and a “broader range of concerns associated with problem behaviors and conditions” (NASEM, 2019, p. 16). Promoting MEB health and well-being in the United States is a focus of a wide range of government and private-sector entities and dedicated prevention workers across a variety of community settings. MEB disorders are at the heart of several ongoing national crises, and the rising prevalence affects every population group, community, and neighborhood in urban, rural, and suburban areas. Treatment and harm reduction are needed to help those who are suffering

___________________

1 Infrastructure here refers to “systems, competencies, frameworks, relationships, and resources that enable state and local governments and agencies, along with communities, community-based organizations, and their partners, to perform core functions” central to preventing MEB disorder and promoting health and well-being (NACCHO, n.d.).

or in imminent danger of harm, but to reduce incidence—to keep problems from happening in the first place—primary prevention and health promotion are essential.2

The good news is, many MEB disorders can be prevented, and the benefit of doing so is indisputable, measured in lives and resources saved (TFAH, 2009). Unfortunately, despite proven benefits to prevention, a fragmented, unevenly developed, and inadequately funded infrastructure along with deficits in implementation (e.g., to move proven interventions into practice) impede prevention efforts at the federal, state, local, and tribal levels.

Other National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) reports have focused on evidence-based approaches for promoting MEB well-being in young people (of note, the report series that includes Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders [IOM, 1994], Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People [NRC and IOM, 2009], and Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development in Youth [NASEM, 2019]). This report builds on that foundation by putting forward guidance to support the dissemination, implementation, and sustainment of effective prevention strategies throughout the life course by building a more robust infrastructure. That infrastructure comprises governance and partnerships; funding; data systems; workforce, training, and technical assistance; and the evolving evidence base for both programs to be implemented in a range of settings, and policies that influence the prevalence and distribution of protective and risk factors for MEB health. Risk factors are “characteristics at the biological, psychological, family, community, or cultural level that precede and are associated with a higher likelihood of negative outcomes” and protective factors are “positive countering events” and “characteristics associated with a lower likelihood of negative outcomes or that reduce a risk factor’s impact” and generally support healthy outcomes (SAMHSA, 2019). Protective and risk factors may be fixed or variable/modifiable. Variable risk factors include but are not limited to income level and adverse childhood experiences.

This chapter describes the committee’s charge and the committee’s approach, explains the urgency for action, outlines the prevention ecosystem, and offers a timeline of the history of prevention for MEB disorders and other important milestones.

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

In August 2023, the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies launched this study at the request of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

___________________

2 That is, on interventions intended to prevent and mitigate risk factors for MEB disorders.

(CDC).3 The committee appointed by the National Academies was asked to create an actionable blueprint to develop, support, and sustain a national infrastructure focused on preventing mental illness and SUDs (see Box 1-1 for the complete statement of task). The National Academies accordingly convened this authoring committee, which has expertise in prevention science, implementation science, health and human services research, public health research and policy, the criminal-legal system, substance use and mental health (MH) research, economics and finance, and developing interventions to address behavioral health disparities (see Appendix A for biographical information of each committee member).

This report serves as the committee’s response to the charge. It outlines a path forward for leadership and governance on multiple levels to grow and sustain the infrastructure to prevent MEB disorders. It reviews the landscape of how preventive programs are funded and delivered, who implements them, what policies support and sustain them, and what implementation strategies and other technical assistance are required. Finally, it offers recommendations—for improving and strengthening each of these infrastructure components—to Congress, federal agencies, including the report sponsors, and other partners, including national organizations that represent different categories of public health leaders in state, local, and tribal contexts.

CONTEXT FOR THE STUDY

The Need for Action Now

The United States continues to experience worsening MEB outcomes that affect individuals, families, communities, schools, congregations, and workplaces. These include the increase between 2013 and 2021 in youth reporting persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness in the past year and the increase between 2013 and 2021 in youth seriously considering attempting suicide (CDC, 2024b). Other noteworthy figures include the increase in the overdose death rate between 1999 and 2022 (NIDA, 2024) and the increase in the age-adjusted suicide rate in 2021 and 2022, largely led by males 75 years and older (Zilkha et al., 2024). One recent bright spot has been the decline in

___________________

3 The following centers, institutes, and offices supported the study: CDC: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Office of the Director; NIH: Division of Program Coordination, Planning, and Strategic Initiatives Office of Disease Prevention, Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research, National Cancer Institute Office of the Director, National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research Office of the Director, National Institute of Mental Health Office of the Director, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Office of the Director, National Institute on Drug Abuse Office of the Director, National Institute of Nursing Research Division of Extramural Science Programs, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Office of the Director, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Office of the Director; and SAMHSA Center for Substance Abuse Prevention Office of the Director.

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

The National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will convene an ad hoc committee to develop a blueprint, including specific, actionable steps for building and sustaining an infrastructure for delivering prevention interventions targeting risk factors for behavioral health disorders. In conducting its work, the committee will

- Identify best practices for creating a sustainable behavioral health prevention infrastructure. Review the landscape of behavioral health prevention at different levels (e.g., national and state, including evidence-based prevention services); where different levels of these prevention services (e.g., universal, selected, and indicated services) could be delivered (e.g., within the community, health care settings, justice systems, schools, human services settings); the workforce needed (investment and their training); and the data systems necessary to track prevention needs, outcomes, and program delivery. Informed by this review, the committee will identify the optimal characteristics and components of a sustainable behavioral health prevention infrastructure. For this infrastructure, the committee should consider embedding prevention services within existing systems and settings, establishing an independent prevention delivery system to which existing systems and settings can refer individuals and families for the receipt of prevention services, and/or other possible approaches

the rate of opioid overdose deaths beginning in the second half of 2022 and continuing into 2024 (NIDA, 2024) and sustained decline in 2024 (CDC, n.d.-a).

The effects of increases in MEB disorders include staggering loss of life and significant mental, social, and economic costs for individuals, families, communities, and the nation as a whole (Abramson et al. 2024). In addition to the overall burden for all of the United States, specific sub-populations as described below, such as Black and American Indian and Alaska Native, experience a disproportionate burden of MEB disorders (Dawes et al., 2024; Morales et al., 2020).

Highlighting the Scope of the Problem

- Suicide is the 11th leading cause of death overall (48,100 deaths in 2021), the second leading cause among people ages 10–14 and

- by which behavioral health prevention programs can be delivered and sustained.

- Identify funding needs and strategies. Review current funding sources for prevention, identify ways those funding sources could be better deployed (including ways to facilitate the integration of funding streams at the state level to be more impactful), and identify new or emerging funding sources that could be redirected and deployed in a coordinated effort to support the prevention infrastructure (e.g., use of opioid settlement funds).

- Identify specific research gaps germane to the widespread adoption of evidence-based behavioral health prevention interventions. Identify key policy and implementation knowledge gaps and the resulting research opportunities that could provide the information needed to support the adoption and sustainment of a national prevention infrastructure for behavioral health. Research gaps are expected to be identified in the realms of policy research and health services research (e.g., dissemination and implementation, economic analyses).

- Make actionable recommendations. Recommend how federal and state policies could be expanded or implemented to develop and sustain the prevention infrastructure system, including those that improve financing for evidence-based prevention and support workforce development, data interoperability, and evidence-based policy making. Recommendations for research necessary to fill the prevention services research gaps should also be identified.

- 25–34, and the third leading cause for ages 15–24 (NIMH, n.d.). Suicide deaths have been increasing since the pandemic-related funding and government supports were removed, only to return to prepandemic levels. The U.S. suicide death rate is the highest among 10 peer nations (Gunja et al., 2023).

- In urban areas, White non-Hispanic people have the highest suicide rates (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2017); in rural areas, non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN, per the U.S. Census Bureau) people have the highest rates (CDC, n.d.-b).

- The drug overdose rate in adolescents was 2.40 per 100,000 in 2010 (518 deaths) and increased to 5.49 (1,146 deaths) in 2021 (Friedman et al., 2022).

- Deaths related to alcohol have increased by 29.3 percent from 2016–2017 to 2020–2021 (Esser et al., 2024).

- Firearms are the leading cause of death among children, and more than three-quarters of adults experience stress associated with fear of a mass shooting; 51 percent of children aged 14–17 report fears of a school shooting (OSG, 2024).

- Survey data collected between July 2021 and December 2022 indicate that among adolescents aged 12–17, 21 percent reported symptoms of anxiety in the past 2 weeks and 17 percent reported depression symptoms, and that over the decade between 2011 and 2021, adolescents reporting feelings of sadness and hopelessness increased from 28 to 42 percent (Panchal, 2024).

- The economic cost of mental illness is an estimated $282 billion annually (Abramson et al., 2024).

- The economic cost of opioid use and overdose deaths during 2017 was $1,021 billion (Luo et al., 2021).

- Easy access to firearms makes suicide attempts much more likely to succeed, and half of suicide deaths are from firearms (Miller et al., 2013).

Highlighting the Scope of the Problem in Populations that Experience Disproportionate Burdens

- Between 2020 and 2021, the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths rose more than 14 percent. In 2021, AIAN people had the highest overall rate (56.6 per 100,000), followed by non-Hispanic Black (44.2) and White (36.8) people (Spencer et al., 2022).

- “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander and non-Hispanic AIAN people experienced the largest percentage increases in drug overdose death rates from 2020 through 2021, with rates increasing by 47 percent and 33 percent, respectively” (Spencer et al., 2022, p. 3).

- In 2022, the suicide rate in AI/AN people was 91 percent higher than that of the general population, and suicide is the second leading cause of death for non-Hispanic AI/AN people ages 10–34 (CDC, 2024a; HHS, n.d.).

- In 2022, suicide was the leading cause of death for Asian American youth ages 15–24 years. In 2023, Asian American adults were 50 percent less likely to have received mental health treatment than non-Hispanic White adults (OMH, 2024).

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the precarity of many U.S. families, schools, and communities, and the moment of national crisis offered opportunities to enact policies that have had far-reaching effects, such as the

expansion of the Child Tax Credit White House Executive Order 13985: Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities, and American Rescue Plan Act,4 which provided vital support for early childhood care and education, and Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, which gave state education agencies $122.8 billion in grants to support schools. These policy actions stabilized systems under strain and offered a glimpse of what is possible in strengthening systems of care (ACF, 2021; Randi, 2021).

Although the public- and private-sector institutions, facilities, services, funding, and workforce for addressing the MEB crises are largely focused on treatment (i.e., intervening after problems arise), the foundations for an effective prevention infrastructure may be found at every level of government and in most communities. Promoting well-being is a key aspect of preventing MEB conditions across the life course and the multifaceted solution that this report addresses is infrastructure.

Comparing the United States to Peer Nations

The United States compares unfavorably to most of its peer nations regarding MEB health and well-being and on multiple measures of health, from life expectancy at birth to infant mortality. The economic insecurity many people face from the lack of effective social policy has negative effects on MEB well-being. Examples include the lack of paid parental leave, which has been linked with postpartum depression; and the lack of paid sick leave—dramatically highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic—which makes the United States an extreme outlier compared to approximately four-fifths of the world and most high-income countries, and affects medical recovery and caregiving (Heymann et al., 2020; Hidalgo-Padilla et al., 2023).

International comparisons on MH needs indicate that U.S. people experience high MH needs (37 percent, second only to Australians at 41 percent). Also, they are the most likely to forgo needed MH services because of cost (18 percent, compared to 16 percent of Australians, 13 percent of Canadians, 9 percent of New Zealanders and Britons, and 8 percent of Swiss) (Gunja et al., 2024). Before the need for treatment arises, many other wealthy nations have implemented strategies to promote well-being and prevent MEB disorders. These include public health campaigns and population-level interventions, such as the Netherlands’ “Wellbeing at School” national program that integrates preventive interventions,

___________________

4 American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Public Law 117-2, 117th Cong., 1st sess. (March 11, 2021).

teacher and parent education, and school policy changes (Williams, 2024). A Commonwealth Fund report found that “[s]ome countries have begun to recognize that MEB issues are often rooted in or exacerbated by societal problems such as racism, workplace stress, and unemployment. To promote well-being, leaders have sought to ameliorate such systemic factors while also offering support to those coping with their effects” (Hostetter and Klein, 2021). For example, Australia has launched and funds “headspace centers” that are overseen by a nonprofit and provide both MH services and a variety of social supports, such as helping young people find jobs. This is a nonstigmatizing, community-based approach to supporting the MH and well-being of young people.

Although U.S. public- and private-sector institutions, facilities, services, funding, and workforce for addressing these crises are largely focused on treatment, the foundations for an effective prevention infrastructure may be found at every level of government and in most communities and will be strengthened by the recommendations made by this report.

Why Well-Being?

Well-being is a more holistic way to consider the outcomes of an effective prevention infrastructure, and the report generally mentions MEB health and well-being as a broad label. In the context of health measurement, well-being is a broad construct (see the World Health Organization definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity of health”) (WHO, 2024). There are measures of objective and subjective well-being, and the discussion is focused on the latter. Well-being has been defined as “how people think, feel, and function—at a personal and social level—and how they evaluate their lives as a whole” (Pronk et al., 2021, p. 243) and “a relative state where one maximizes his or her physical, mental and social functioning in the context of supportive environments to live a full, satisfying, and productive life” (Kobau et al., 2010).

MEB health refers to key components of well-being that reflect progress in whether individuals and communities are able to flourish and thrive (Rule et al., 2024). Multiple indicators of MH support this picture. One example is the United States’s poor performance on the World Happiness Index (Helliwell, 2024), which describes well-being in the United States to have steadily dropped, placing the United States 23rd in international standings. Of particular concern is the finding that the well-being of younger U.S. people has declined the most of any age group (Helliwell, 2024), indicating that the nation’s resiliency and strength is in serious jeopardy.

Value of Prevention

The best-known public health typology of prevention levels is primordial, primary, secondary, and tertiary.5 The typology frequently used in the context of MEB health—universal, selective, and indicated—refers to targeting preventive interventions to the entire population, groups at increased risk, and individuals showing early signs of exposure/subclinical condition respectively.

Despite significant efforts to support those suffering with MEB disorders, that work has largely been done at the secondary and tertiary prevention levels. Far greater attention and funding is needed for primordial and primary prevention, and implementing prevention requires partnering with all affected communities to build the capacity and secure and deploy the resources needed to implement evidence-driven programming. In addition to greater resources shifted toward preventive services, a strategic investment will focus especially on communities that are under-resourced and/or have historically experienced disinvestment. This is critical to not only prevent disorder, disability, reduced quality of life, and unnecessary deaths but to promote well-being. Investing in the implementation, infrastructure, and programs to support the scale-up of prevention has a clear return on investment not only from a cost-savings perspective but also in disability-adjusted life years averted. For example, a study modeling the return on investment on preventing and treating adolescent MH disorders and suicide using a package of evidence-based interventions across 36 countries that account for 80 percent of the burden measured in disability-adjusted life years showed $23.6 return per $1 spent over 80 years (Stelmach et al., 2022).6

THE PREVENTION ECOSYSTEM7

Within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), NIH includes several institutes, centers, and offices with missions relevant

___________________

5 That is, on interventions intended to prevent and mitigate risk factors for MEB disorders. Primordial prevention = interventions that address social conditions and root causes of disorders; primary prevention = interventions to reduce risk factors and promote protective factors to prevent the onset of disease; secondary prevention = interventions that identify disease before it is symptomatic to treat early and reduce severity; tertiary prevention = interventions to prevent significant adverse consequences once a disease has been established.

6 In addition to MEB health investments, evidence-based prevention programs to increase physical activity, prevent smoking, and improve nutrition can yield $5.60 in savings on every $1 spent (TFA, 2008).

7 While prevention research, science, and practice sometimes does not always distinguish between MEB and physical health outcomes, the focus of this description is on entities that address MEB disorder prevention.

to prevention; SAMHSA has a Center for Substance Abuse Prevention and preventive functions within the Center for Mental Health Services, and CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control operates the agency’s behavioral health (BH) coordinating unit. Several other federal agencies also conduct prevention-related research or provide services (see Chapter 2 for a sample of clearinghouses of evidence-based prevention programs managed by federal agencies). The Indian Health Service Division of Behavioral Health includes a focus on primary prevention of MEB disorders. The state and local levels have BH agencies or public health agencies with BH units. There are also national associations (e.g., the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors, the National Association of State Mental Health Directors, CADCA, formerly known as the Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America), research groups, such as the Society for Prevention Research, and the academic networks of Prevention Technology Transfer Centers (and to a lesser extent the Mental Health Technology Transfer Centers, which were shuttered in September 2024),8 as well as the prevention research centers, etc. This rich ecosystem (see Table 1-1) is better developed for the substance use components of the prevention end of the continuum, and it will take better coordination, more robust and sustainable funding, and more integrated governance of prevention functions at the federal level and with state and tribal partners to move toward a stronger prevention infrastructure.

A Brief History and Milestones

The United States was not always so predominantly focused on treatment of MEB disorders. In the interwar period leading into the Second World War, the approach to MH was focused on mental hygiene in workers so that society could nurture a productive workforce. As the medical field advanced, however, the focus shifted to the individual level, and medical breakthroughs and exposés on horrid conditions within institutions for the mentally ill led to the closure of many of them (Harrington, 2023). The Community Mental Health Act of 1963 represented a change that, in theory, brought treatment into the community, shifting it out of state hospitals. But states and the federal government did not create enough or adequately resource community capacity to take care of deinstitutionalized patients or respond to the considerable needs of people with serious mental illness (IOM, 1991).

Although the onus is not on individual practitioners, the following quote highlights a recognition of the broad context in which MEB disorders arise: “[P]sychiatrists must . . . distinguish between those areas in which [system and structural] social forces rather than psychiatric illness are at

___________________

8 See https://mhttcnetwork.org/ for more info (accessed October 14, 2024).

TABLE 1-1 The Prevention Ecosystem in Which the MEB Prevention Infrastructure Is Embedded

| Part of Ecosystem | Sample Relevant Entities |

|---|---|

| Governance and funding: federal and tribal | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Indian Health Service, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Administration for Children and Families, and Administration for Community Living |

| U.S. Departments of Veterans Affairs; Defense; Education; Agriculture; Justice | |

| White House Office of National Drug Control Policy | |

| Governance and funding: state | Single state agency for substance use, MH, or substance use & MH |

| State public health agency | |

| State Medicaid | |

| Governance, funding, and partnerships: local | Coalitions (e.g., on substance use disorder/Drug Free Communities; violence prevention) |

| Accountable communities for health | |

| Other community entities, such as community health needs assessment advisory groups. Could include other types of partnerships or networks in a variety of systems/settings or associated with individual agencies | |

| Knowledge creation | NIH (multiple institutes and centers, e.g., National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, Office of Disease Prevention, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities); CDC; research entities in other federal government departments |

| Academic institutions | |

| Other evidence-based intervention developers | |

| Practice-based research networks and partnerships | |

| Knowledge translation, technical assistance for service delivery | SAMHSA-funded Prevention Technology Transfer Centers |

| NIH Clinical and Translational Service Awards program and AHRQ Healthcare Extension Service | |

| CDC-funded Prevention Research Centers | |

| Bi-regional centers supported by SAMHSA Center for Mental Health: Dissemination, Implementation, and Sustainment | |

| Other training and technical assistance providers | |

| Community health centers | |

| Clearinghouses |

| Part of Ecosystem | Sample Relevant Entities |

|---|---|

| Knowledge sharers/dissemination | SAMHSA National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory, Society for Prevention Research |

| Society for Research in Child Development and other research organizations | |

| National Prevention Science Coalition to Improve Lives | |

| National associations: National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Agency Directors, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, National Association of City and County Health Officials, National Association of County Behavioral Health and Disability Directors, CADCA, National Indian Health Board, National Council of Urban Indian Health, Association of State and Territorial Health Officials | |

| Systems and settings | Human services (child welfare, aging services) |

| Public health | |

| Education | |

| Criminal-legal | |

| Health care (including national associations) | |

| Tribal |

NOTES: This table should not be considered an exhaustive description of the ecosystem. MEB = mental, behavioral, and emotional.

fault . . . then the psychiatrist must be willing to try to meet social needs and handle the wide range of psychiatric problems” (Erickson, 2021, p. 7).

Structuring governance for the field has also long been a key concern, as SAMHSA, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism were once grouped together under the same agency, in a long-evolving effort to find the optimal forms of governance and funding for MEB health research, prevention, and treatment services (see Table 1-2). The history of the field reflects broader tensions between the biomedical and population health paradigms and between pathologizing approaches focused on the individual compared with a broad focus on social and environmental factors that shape risk for and protection from MEB disorders (Acolin and Fishman, 2023).

THE COMMITTEE’S APPROACH

The statement of task called on the committee to describe an infrastructure to deliver preventive interventions that target risk factors and enhance protective factors for behavioral disorders. In considering terminology for

TABLE 1-2 Timeline of Milestones in the History of MEB Health in the United States

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1944 | The Public Health Service Act enacted (Title V establishes Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]) |

| 1946 | National Mental Health Care Act, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and National Advisory Mental Health Council |

| 1949 | NIMH opens |

| 1952 | First Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I) published |

| 1963 | Community Mental Health Act enacted |

| 1965 | First Neighborhood Health Centers launched Medicare and Medicaid Act enacted |

| 1966 | National Center for Prevention and Control of Alcoholism, and Center for Studies of Narcotic Addiction and Drug Abuse launched |

| 1968 | NIMH reorganized, with a focus on service delivery |

| 1970 | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) established |

| 1972 | NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse) established (within NIMH) |

| 1973 | NIMH reorganized back to NIH |

| 1974 | Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration (ADAMHA) created, contained NIMH, NIDA, and NIAAA |

| 1977 | President’s Commission on Mental Health created |

| 1992 | ADAMHA Reorganization Act—NIMH, NIDA, and NIAAA move back to NIH, while service components become part of SAMHSA (a Public Health Service agency); Act includes support for home visiting services (see Chapter 2) |

| 1996 | Health Centers Consolidation Act (under Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act, health centers serving communities, migrants, unhoused people, and public housing residents) |

| 1996 | Mental Health Parity Act enacted |

| 1999 | First U.S. Surgeon General’s report on mental health released |

| 2000 | Children’s Health Act of 2000 enacted |

| 2002 | President’s New Freedom Commission on MH created |

| 2004 | Mentally Ill Offender Treatment and Crime Reduction Act signed into law to provide resources for alternatives to incarceration for youth and adults with mental disorders/SUD |

| 2006 | Sober Truth on Preventing Underage Drinking Act |

| 2008 | Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act enacted |

| 2009 | American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (increased Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, expanded Earned Income Tax Credit) enacted |

| 2010 | Affordable Care Act enacted, creating the National Prevention, Health Promotion, and Public Health Council (NPC) |

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 2010 | Tribal Law and Order Act enacted, calling for “interagency coordination and collaboration between the Department of Justice, the Department of the Interior, and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)” to focus attention to “justice, safety, education, youth, and alcohol and substance abuse prevention and treatment issues relevant to Indian country” |

| 2016 | Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act enacted |

| 2018 | Support for Patients and Communities Act signed into law |

| 2021 | Protecting Youth Mental Health—Surgeon General’s Advisory9 |

| Behavioral Health Coordinating Council established in HHS to coordinate “all federal government resources to address inequities and gaps within the mental health and substance use disorder system” | |

| 2021 | HHS Overdose Prevention Strategy announced |

| 2022 | Roadmap to Behavioral Health Integration developed, and Behavioral Health Coordinating Council tasked with its implementation |

| Restoring Hope for Mental Health and Wellbeing Act | |

| Surgeon general’s framework Workplace Mental Health & Well-Being | |

| 2023 | Surgeon General issues new advisory about effects of social media use on youth mental health |

| 2024 | National Strategy for Suicide Prevention announced, and federal action plan released |

| Surgeon General: Why I’m Calling for a Warning Label on Social Media Platforms | |

| Surgeon General issues advisory on the public health crisis of firearm violence in the United States |

NOTE: MEB = mental, emotional, and behavioral.

SOURCES: NIMH, n.d.; NIDA, 2025.

this report, particularly the use of “mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) disorders” or “MEB health,” the committee noted the use of the phrase “behavioral health disorders” in the statement of task, sponsors’ remarks to the committee at the first meeting, and context provided by related National Academies reports that provide detailed reviews of the evidence base of interventions (NASEM, 2019; NRC and IOM, 2009).

___________________

9 From the Advisory: “A Surgeon General’s Advisory is a public statement that calls the American people’s attention to an urgent public health issue and provides recommendations for how it should be addressed. Advisories are reserved for significant public health challenges that need the nation’s immediate awareness and action” https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf (accessed February 28, 2025).

“Behavioral” or “mental” disorders include a variety of conditions defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and the International Classification of Diseases with clear diagnostic criteria, which can be diagnosed in clinical settings by health care providers. Federal and state agencies, advocacy groups, professional organizations, and other groups use broader terminology to avoid stigma and ensure relevance to a wider audience (see later for examples of some audiences of this report). Accordingly—and, as Fostering Health Mental Emotional, and Behavioral Development in Children and Youth did—this report primarily uses “mental, emotional, and behavioral” to describe “both disorders diagnosable using [DSM-V] criteria and the problem behaviors associated with them, such as violence, aggression, self-injury, suicide, and antisocial behavior” (NASEM, 2019, p. 16), thus encompassing mental illness, SUDs, and a broader range of concerns associated with problem behaviors and conditions. This is also reflected in the prevention science field, which largely targets risk and protective factors (which are the same for many conditions and disorders).

The committee offers a blueprint to implement and sustain prevention of MEB disorders in the United States. The infrastructure includes evidence-based programs and policies, funding, workforce, data, and governance and partnerships. The committee did not conduct a comprehensive review of programs, but rather focused on a sampling of different types of programs to illustrate the extant evidence base; the needs for the workforce, data systems, funding, and governance; and needs for future research and the dissemination of evidence. The committee briefly examined high-level economic and social policies that are interventions delivered by policy makers who allocate taxpayer funding to support them and are informed by high-level data, such as Census data and Congressional Budget Office cost calculations. Although the report primarily focuses on the infrastructure for delivering evidence-based programs, the committee interpreted its charge in the light of sponsor remarks at its first open information-gathering meeting in December 2023. In response to clarifying questions from the committee, NIDA director Nora Volkow and SAMHSA Center for Substance Abuse Prevention director Captain Christopher Jones shared reflections on the population-level and structural factors, such as poverty and exposure to adverse childhood experiences, that shape BH outcomes, and the interventions that operate upstream of the disease process.

Given the clarification and urging by the study’s sponsors, the committee focused on primary, and, to a lesser extent, primordial and secondary prevention. In addition to describing and making recommendations about the infrastructure needed to support the delivery of preventive programs, the committee also made policy-related recommendations relevant to preventing risk factors and enhancing protective factors. The committee was informed

by the socio-ecological model of health that shows the levels of influences on trajectories to certain kinds of outcomes at every level from intrapersonal (genetic and biological—not discussed in this report because they are not modifiable), to interpersonal (e.g., family), institutional, community, and ultimately, public policy. Sloboda (2009) provides an extensive discussion of socialization and related processes and mechanisms that influence behavior along the life course and identifies the points where interventions can be applied.

The committee asserts, echoing the sponsors’ comments at the giving of the charge, that social, economic, and environmental policies constitute “upstream” or primordial prevention. Policies may be considered interventions because their enactment can lead to changed outcomes at a population level. But policies also shape the broader social and economic context within which programs are implemented, workers deliver services, and other components of the infrastructure operate. This explains why the report treats policies differently from programs. The report’s closing chapter (7) recognizes policy as context for the infrastructure. An in-depth discussion of policy makers as “workforce,” national data systems (with the U.S. Census as foundation), and funding needed for high-level policies seemed out of scope or at least unreasonably broad for the present report. Chapter 7 outlines policies that could enhance MEB health opportunities for all. These include evidence-based early-life investments such as home-visiting programs and quality early childhood care and education, and policies and investments that are impactful later in life such as Social Security and housing vouchers. The chapter discusses in more detail the broad categories (and specific examples) of policies shown to have direct effects on MEB outcomes.

The committee approached its task with a few guiding principles front and center in developing this report. The first two are perhaps the most important. First, the use of lessons learned from implementation science (IS) is crucial if the infrastructure and delivery systems it supports are to achieve their goals. IS, a “systematic, scientific approach to ask and answer questions about how we get ‘what works’ to people who need it, with greater speed, fidelity, efficiency, quality and relevant coverage” (UWDGH, 2024). IS provides not only key insights into implementing discrete interventions or policies but also strategies to sustain a successful infrastructure. IS offers frameworks and approaches that can be used to support sustaining delivery of the intervention as intended and adapting it intentionally and rigorously in response to community and population need. Second, achieving health equity—“the state in which everyone has a fair opportunity to attain full health potential and well-being, and no one is disadvantaged from doing so because of social position or any other socially defined circumstance”—is a key objective of the infrastructure to prevent MEB disorders and promote

MEB well-being (NASEM, 2023). Each chapter includes these guiding principles.

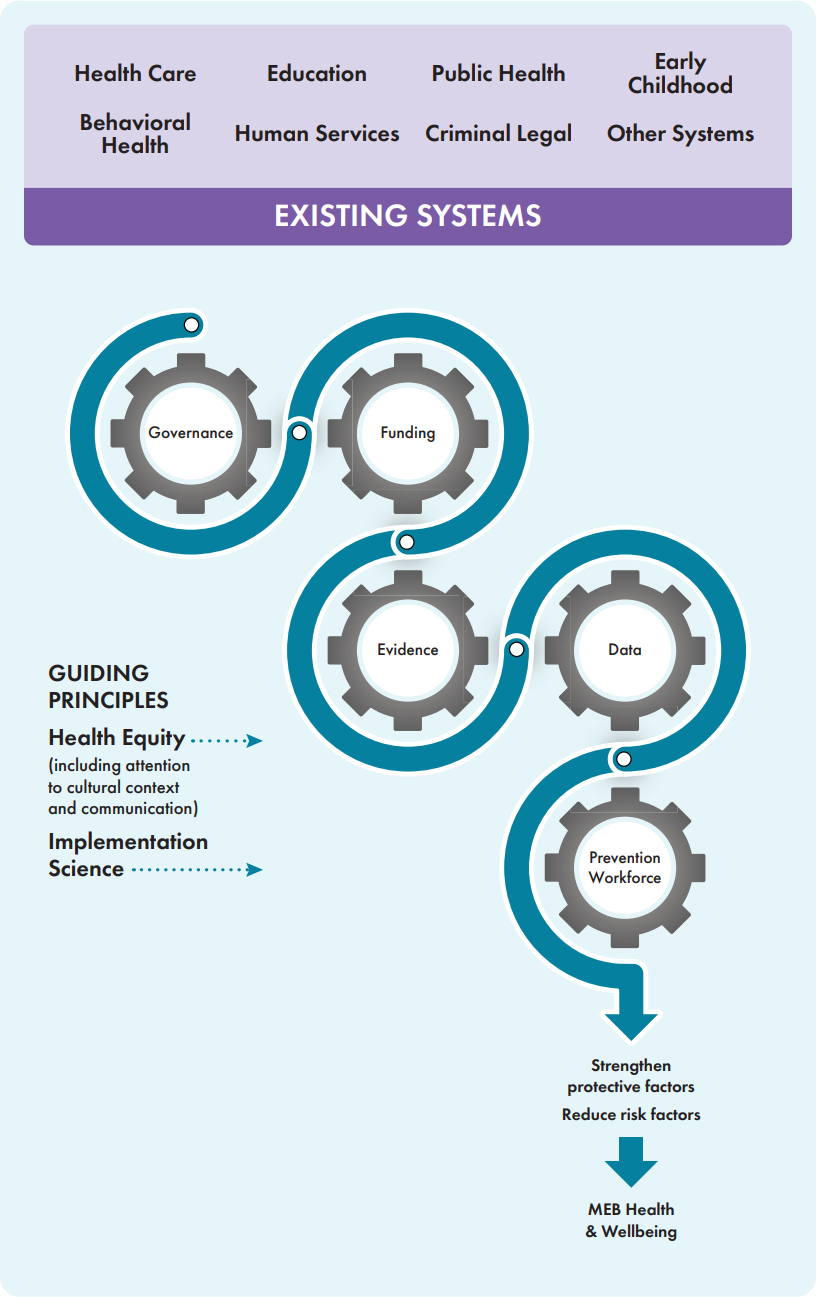

The statement of task asked the committee to “consider embedding prevention services within existing systems and settings, establishing an independent prevention delivery system to which existing systems and settings can refer individuals and families for the receipt of prevention services, and/or other possible approaches by which behavioral health prevention programs can be delivered and sustained.” As shown in Figure 1-1, the committee’s information gathering demonstrated that existing systems (e.g., education, human services) and settings provide a good foundation for the prevention infrastructure. The committee viewed creating an independent delivery system as inefficient and suboptimal. Taking workforce as an example, teachers and staff in education settings are well placed to implement interventions that are both promotive and protective.

Other principles reflected across and within each chapter: prevention is inherently multidisciplinary (NASEM, 2019; NRC and IOM, 2009); it cannot happen successfully without community-driven partnerships or considerations related to local and cultural contexts.

This report describes the components needed to successfully support the implementation of approaches to prevent MEB disorders and promote MEB health on a national scale. Boxes in each chapter highlight (1) needs and considerations for the successful implementation and sustainment of evidence-based interventions, and (2) specific interventions/approaches that are intended to be illustrative and may be useful to communities and their partners. The evidence-based programs mentioned in the report were selected for illustrative purposes only, for being evidence-based or promising, and for exemplifying strategies for a variety of settings and populations. The committee does not endorse these specific sample programs, but shares them to illustrate the types of interventions that are available, and to help explore implementation, workforce, and other dimensions.

The committee conducted four public information-gathering meetings, extensive reviews of the literature, public listening sessions and staff conversations with additional stakeholders or constituents, and closed working meetings to deliberate and write the report.

A Vision for the Prevention Infrastructure for MEB Disorders

A national MEB prevention infrastructure requires “systems, competencies, frameworks, relationships, and resources that enable [state and local governments and agencies, along with communities, community-based organizations, and their partners,] to perform core functions” central to preventing MEB disorder and promoting health and well-being (NACCHO, n.d.).

NOTES: This graphic illustrates (1) the major components of the infrastructure that is embedded in existing systems and operates across varied settings, delivering interventions along the life course, and (2) the guiding principles that should permeate it. The interlocking gears represent how each element is complementary and critical to the others: governance and partnerships at federal, state, local, and tribal levels; sustained funding; supportive data systems; a constantly evolving evidence base; and a competent, supported workforce comprise a flexible and responsive infrastructure to prevent MEB disorders. The blueprint for such an infrastructure includes guidance on turning, engaging, and fine-tuning the “gears” to foster implementation of preventive strategies that is fully responsive to the communities that need them. The infrastructure operates in the context of policies (not included in the graphic) that shape the economic, social, and environmental conditions that enhance protective factors against or present risk factors for MEB disorders. MEB = mental, emotional, and behavioral.

This report proposes recommendations to support a well-functioning prevention infrastructure, which

- Is organized around delivering evidence-based programs that are effectively disseminated, continually evaluated, and well known, with easily accessed details about effectiveness and implementation, and feedback loops that add to the evidence base (a feature of a learning prevention infrastructure) (Chapter 2), and operate in a supportive policy environment (Chapter 7);

- Has a workforce that is appropriately trained to deliver those strategies, representative of the populations served, and able to provide linguistically and culturally appropriate services,10 fairly paid, supported, and provided with career ladders (Chapter 3);

- Has data systems that draw on all existing resources to inform needs assessment and selection of strategies, and to support evaluation and accountability (Chapter 4);

- Has clear governance structures at the federal, state, tribal, and local levels, including shared governance through cross-sector and community partnerships (Chapter 5);

- Is adequately and sustainably funded (Chapter 6);

___________________

10 The committee endorses the recommendation in the recent National Academies report that called on CMS and SAMHSA to “restructure current workforce and training mechanisms and their funding to better incentivize robust training environments that support career choices that will more directly impact care for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries” (NASEM, 2024, p. 241). The restructuring, the committee said, should “focus on the providers serving populations with highest need for greater access to behavioral health provision in Medicaid such as rural, child/adolescent, and racial/ethnic minoritized populations” and “focus on workforce demographic diversity.”

- Exists in the context of supportive evidence-based policies that create and strengthen the social, economic, and environmental conditions necessary for MEB disorder prevention and undergird population health (Chapter 7); and

- Prioritizes implementation with an emphasis on (communities and populations) at highest risk—collaborating and co-creating with communities at each step, from pre-implementation (assessing readiness, defining the problem and goals) to implementation planning (e.g., training, resource distribution), to implementation (discussed throughout the report).

The committee identified a prevention infrastructure that is fragmented and better developed for substance use disorders (SUD) than for MH—and it is embedded in a broad ecosystem of public and private entities and networks. It can be nurtured, strengthened, and robustly funded to close gaps and provide the interventions and packages of interventions needed in every community and at every level of society, with a focus on greater support for areas of greatest need.

It includes parts of several other infrastructures, including public health, health care, social and human services, and education. The major infrastructure components are funding, governance, data, the workforce, and the evidence base; together, these allow for sustained delivery of interventions affecting both upstream and downstream factors related to MEB health. Expanding opportunities for all to reach their full health potential, local and cultural contexts, and community-driven partnerships are necessary throughout these components. For example, workers drawn from the community bring deep knowledge and earned trust. The evidence base must reflect the communities to whom interventions are being delivered and must determine whose voices, perspectives, and contributions shape or lead these decisions.

The charge to the committee underscores the lack of uptake of proven prevention interventions, and that, the committee shows, is fundamentally an implementation issue—having to do with adequate, sustained funding; reliable dissemination of the evidence base with feedback loops to update it and fill gaps; data access, collection, and use to inform decision making and implementation; a well-trained and fairly compensated workforce with opportunities for growth; and a structure of oversight and leadership—governance—that is well coordinated, integrates MH and SUD functions and organizations, and engages community voice and lived expertise.

HOW TO USE THIS REPORT

It is important to first identify partners in the prevention ecosystem who will implement and/or are affected by implementation (as discussed below in the “map constituents” step for supporting the infrastructure).

The ecosystem includes many of the constituents and audiences for the report. In addition to this report’s sponsors, which include several institutes, centers, and offices across NIH, CDC, and SAMHSA, it may be of interest to other federal entities such as other HHS agencies, the Department of Agriculture, Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense, Department of Education, and Department of Justice. This blueprint for the prevention infrastructure will also be useful to state leaders and decision makers, researchers, community coalitions, prevention research centers, academic and community partnerships, government and academic partnerships, and philanthropic and community organizations. It also could be useful to community leaders and members, and other implementers and partners who are not, strictly speaking, responsible for the infrastructure per se but interact with it in various ways.

As noted, this report emphasizes health equity (“the state in which everyone has a fair opportunity to attain their full potential for health and well-being and no one is disadvantaged from doing so because of social position or other socially defined circumstances” [NASEM, 2023]) and applying implementation science in the infrastructure and the interventions. Considerations related to these two points of emphasis appear throughout the report.

When thinking about supporting the prevention infrastructure or delivering interventions in communities, any constituents will benefit from referring to lessons from implementation processes. On multiple levels—the “meta,” or the infrastructure; the “macro,” or social policy; or the “meso” and “micro,” as more discrete interventions implemented on a community level—the overarching steps are the same, but the steps are characterized here with some detail as it would apply to the meta level (e.g., the sustainers, funders, or builders of the infrastructure).

- Identify the gap or need: Sustainers must gather data and establish priorities for the infrastructure itself, which this report in part helps to do. A key component for identifying needs or gaps is doing so in a way that is community driven.

- Select the intervention: Sustainers will consider the major components of the infrastructure (chapter topics in this report) to address identified needs and may look to recommendations from this report and other expert advice or resources to inform selection as well. This step might include redirecting funds or issuing new funds for practice or research, developing methods or support for data collection, or identifying criteria for workforce development. Sustainment is also something to consider during this step, such as designing for dissemination and sustainability of updated or new evidence on preventive interventions (Kwan et al., 2022).

- Map the constituents: Sustainers will likely have done some version of this already but will need to map the constituents invested in the

- infrastructure (see Table 1-1 for examples) to identify partners and assets, increase buy-in, and ensure that the approaches to support the infrastructure are addressing the needs of its constituents.11

- Assess barriers and facilitators, and understand context: Barriers and facilitators, or “determinants,” enable or hinder adoption, implementation, and sustainment of approaches to support the infrastructure. As part of the process, sustainers must have rapid ways to measure their context and those determinants. There are many tools to help support this assessment, such as a pragmatic context assessment tool (see pCAT12).

- Create a logic model: Once sustainers have identified determinants, they can create a logic model for implementation. Smith and colleagues offer one example, but the crucial component is intentionally and prospectively mapping out the whole approach based on the work already done so there is a clear path forward (Smith et al., 2020).

- Evaluate: Sustainers will need consistent metrics to evaluate if their approaches to support the infrastructure are effective. They will also need to select and assess data in partnership with different constituents—this may include the data discussed in Chapter 4 and also data about research funding and outcomes, governance, and the workforce that are not specific to outcomes from specific interventions.

- Adapt: As sustainers begin to collect data and other information about the outcomes of their approaches to support prevention research translation, dissemination, and sustainment, they will need to adapt to ensure maximum success and fit to context.

- Sustain: Sustainment is a key consideration at both the end and the beginning of the process; it is important to plan for it from the start. Sustainers can use tools such as a program sustainability assessment tool to help with planning (e.g., PSAT) (PSAT, n.d.).

This list is semilinear, in that implementers will often be engaged in more than one step at one time. This type of process is a continuous cycle of engagement, supported by data and partnerships with groups that can help with interpretation, adaptation, and ongoing iteration to maintain the infrastructure’s adaptability for new evidence and ways to support the delivery of interventions.

___________________

11 See Potthoff and colleagues (2023) for one example of a constituent engagement model.

12 See https://cfirguide.org/tools/tools-and-templates/ (accessed October 28, 2024). As of October 28, 2024, the tool is updated; in the interim, follow instructions in link to see the tool in “Additional File 2” from Robinson and Damschroder (2023).

REPORT OVERVIEW

The report contains seven chapters and six appendixes. Chapter 2 provides a brief overview of the evidence base for prevention programs and strategies, along with a discussion of IS and the guidance it offers to ensuring that implementation is robust and includes all keys to success and sustainment. Chapter 3 discusses the workforce for prevention, which is considerably different from the traditional, largely clinical, licensed professions in BH (psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, etc.). Chapter 4 discusses the data infrastructure to support the delivery of interventions in a wide range of settings. Chapter 5 discusses the governance and partnerships that set the pace, motivate, and lead the way at different levels. Chapter 6 identifies the gaps in funding that need to be addressed, especially by Congressional and state-level attention, and generating additional resources and devoting them to this essential work. Finally, Chapter 7 offers a brief overview of the social, economic, and environmental policies that create the conditions for primordial prevention of MEB health and population well-being.

REFERENCES

Abramson, B., J. Boerma, and A. Tsyvinski. 2024. Macroeconomics of mental health. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w32354/w32354.pdf (accessed December 30, 2024).

ACF (Administration for Children and Families). 2021. Child care stabilization grants appropriated in the American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act (Public Law 117-2) signed into law on March 11, 2021. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/occ/CCDF-ACFIM-2021-02.pdf (accessed December 30, 2024).

Acolin, J., and P. Fishman. 2023. Beyond the biomedical, towards the agentic: A paradigm shift for population health science. Social Science & Medicine 326:115950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115950.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1992. A framework for assessing the effectiveness of disease and injury prevention. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 41. https://www.cdc.gov/mmWR/preview/mmwrhtml/00016403.htm (accessed December 30, 2024).

CDC. 2024a. Tribal suicide prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/programs/tribal.html (accessed December 16, 2024).

CDC. 2024b. Youth risk behavior survey data summary & trends report. https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs/dstr/index.html (accessed December 30, 2024).

CDC. n.d.-a. Provisional drug overdose death counts. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm (accessed October 28, 2024).

CDC. n.d.-b. Suicide in rural America. https://www.cdc.gov/rural-health/php/public-healthstrategy/suicide-in-rural-america-prevention-strategies.html (accessed October 28, 2024).

CFIR (Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research). 2025. Tools and templates. https://cfirguide.org/tools/tools-and-templates/ (accessed January 2, 2025).

Dawes, D. E., J. Bhatt, N. J. Dunlap, C. Amador, K. Gebreyes, B. Rush, J. Westfall, M. Fendrich, A. Davis, M. Keita Fakeye, C. Philip, N. Wade, D. Hernandez, and A. Dhar. 2024. Projected cost and economic impact of mental health inequities in the United States. https://meharryglobal.org/research-scholarship/projected-cost-and-economic-impact-of-mental-health-inequities/ (accessed January 2, 2025).

Erickson, B. 2021. Deinstitutionalization through optimism: The Community Mental Health Act of 1963. American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal 16(4):6–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2021.160404.

Esser, M. B., A. Sherk, Y. Liu, and T. S. Naimi. 2024. Deaths from excessive alcohol use–United States, 2016–2021. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 73(8):154–161. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7308a1.

Friedman, J., M. Godvin, C. L. Shover, J. P. Gone, H. Hansen, and D. L. Schriger. 2022. Trends in drug overdose deaths among US adolescents, January 2010 to June 2021. JAMA 327(14):1398–1400. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.2847.

Gunja, M. Z., E. D. Gumas, and R. D. Williams II. 2023. U.S. health care from a global perspective, 2022: Accelerating spending, worsening outcomes. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2022 (accessed December 30, 2024).

Gunja, M. Z., E. D. Gumas, and R. D. Williams II. 2024. Mental health needs in the U.S. compared to nine other countries: Findings from the commonwealth fund 2023 international health policy survey. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2024/may/mental-health-needs-us-compared-nine-other-countries (accessed December 16, 2024).

Harrington, A. 2023. Mental health’s stalled (biological) revolution: Its origins, aftermath & future opportunities. Daedalus. 2023;152(4):166–185. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_02037.

Helliwell, J. F., R. Layard, J. D. Sachs, J-E. De Neve, L. B. Aknin, & S. Wang. 2024. World happiness report 2024. University of Oxford: Wellbeing Research Centre.

Heymann, J., A. Raub, W. Waisath, M. McCormack, R. Weistroffer, G. Moreno, E. Wong, and A. Earle. 2020. Protecting health during Covid-19 and beyond: A global examination of paid sick leave design in 193 countries. Global Public Health 15(7):925–934. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1764076.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). n.d. Mental and behavioral health–American Indians/Alaska Natives. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/mental-and-behavioral-health-american-indiansalaska-natives (accessed December 16, 2024).

Hidalgo-Padilla, L., M. Toyama, J. H. Zafra-Tanaka, A. Vives, and F. Diez-Canseco. 2023. Association between maternity leave policies and postpartum depression: A systematic review. Archives of Women’s Mental Health 26(5):571–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-023-01350-z.

Hostetter, M., and S. Klein. 2021. Making it easy to get mental health care: Examples from abroad. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/feb/making-it-easy-get-mental-health-care-examples-abroad (accessed December 30, 2024).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1991. Research and service programs in the PHS: Challenges in organization. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/1871.

IOM. 1994. Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/2139.

Ivey-Stephenson, A. Z., A. E. Crosby, S. P. D. Jack, T. Haileyesus, and M. J. Kresnow-Sedacca. 2017. Suicide trends among and within urbanization levels by sex, race/ethnicity, age group, and mechanism of death–United States, 2001–2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries 66(18):1–16. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6618a1.

Jackson-Morris, A., C. L. Meyer, A. Morgan, R. Stelmach, L. Jamison, and C. Currie. 2024. An investment case analysis for the prevention and treatment of adolescent mental disorders and suicide in England. European Journal of Public Health 34(1):107–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckad193.

Kobau, R., J. Sniezek, M. M. Zack, R. E. Lucas, and A. Burns. 2010. Well-being assessment: An evaluation of well-being scales for public health and population estimates of well-being among US adults. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 2:272–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01035.x.

Kwan, B. M., R. C. Brownson, R. E. Glasgow, E. H. Morrato, and D. A. Luke. 2022. Designing for dissemination and sustainability to promote equitable impacts on health. Annual Review of Public Health 43(1):331–353. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurevpublhealth052220-112457.

Luo, F., M. Li, and C. Florence. 2021. State-level economic costs of opioid use disorder and fatal opioid overdose–United States, 2017. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 70(15):541–546. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7015a1.

MHTTC (Mental Health Technology Transfer Center). 2024. Mental Health Technology Transfer Center. https://mhttcnetwork.org/ (accessed January 2, 2025).

Miller, M., C. Barber, R. A. White, and D. Azrael. 2013. Firearms and suicide in the United States: Is risk independent of underlying suicidal behavior? American Journal of Epidemiology 178(6):946–955. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt197.

Morales, D. A., C. L. Barksdale, and A. C. Beckel-Mitchener. 2020. A call to action to address rural mental health disparities. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 4(5): 463–467. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2020.42.

NACCHO (National Association of County and City Health Officials). n.d. Public health infrastructure and systems. https://www.naccho.org/programs/public-health-infrastructure (accessed November 22, 2024).

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2019. Fostering healthy mental, emotional, and behavioral development in children and youth: A national agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25201.

NASEM. 2023. Federal policy to advance racial, ethnic, and tribal health equity. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26834.

NASEM. 2024. Expanding behavioral health care workforce participation in Medicare, Medicaid, and marketplace plans. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27759.

NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse). 2024. U.S. Overdose deaths by sex, 1999–2022. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates#Fig1 (accessed December 12, 2024.)

NIDA. 2025. NIDA has supported scientific research on drug use and addiction for 50 years, https://nida.nih.gov/about-nida/50th-anniversary (accessed January 3, 2025).

NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health). 2024. Celebrating 75 years: Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/NIMH-Celebrating-75-Years-508_0.pdf (accessed January 2, 2025).

NIMH. n.d. Suicide. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide (accessed October 22, 2024).

NRC (National Research Council) and IOM. 2009. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12480.

OMH (HHS Office of Minority Health). 2024. Mental and behavioral health–Asian Americans. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/mental-and-behavioral-health-asian-americans (accessed December 30, 2021).

OSG (Office of the Surgeon General). 2024. Firearm violence: A public health crisis in America. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/firearm-violence-advisory.pdf (accessed December 30, 2021).

Panchal, N. 2024. Recent trends in mental health and substance use concerns among adolescents. KFF. https://www.kff.org/mental-health/issue-brief/recent-trends-in-mental-health-and-substance-use-concerns-among-adolescents/ (accessed December 30, 2024).

Potthoff, S., T. Finch, L. Bührmann, A. Etzelmüller, C. R. van Genugten, M. Girling, C. R. May, N. Perkins, C. Vis, and T. Rapley. 2023. Towards an Implementation-Stakeholder Engagement Model (I-STEM) for improving health and social care services. Health Expectations 26(5):1997–2012. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13808.

Pronk, N., D. V. Kleinman, S. F. Goekler, E. Ochiai, C. Blakey, and K. H. Brewer. 2021. Promoting health and well-being in healthy people 2030. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 27(Supplement 6):S242–S248. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001254.

PSAT (Program Sustainability Assessment Tool). n.d. Find planning resources. https://www.sustaintool.org/psat/resources/ (accessed October 28, 2024).

Randi, O. 2021. American rescue plan act presents opportunities for states to support school mental health systems. NASHP. https://nashp.org/american-rescue-plan-act-presents-opportunities-for-states-to-support-school-mental-health-systems/ (accessed December 30, 2024).

Robinson, C. H., and L. J. Damschroder. 2023. A pragmatic context assessment tool (PCAT): Using a think aloud method to develop an assessment of contextual barriers to change. Implementation Science Communications 4(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-022-00380-5.

Rule, A., C. Abbey, H. Wang, S. Rozelle, and M. K. Singh. 2024. Measurement of flourishing: A scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology 15:1293943. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1293943.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2019. Risk and protective factors. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/20190718-samhsa-risk-protective-factors.pdf (accessed December 12, 2024).

Smith, J. D., D. H. Li, and M. R. Rafferty. 2020. The implementation research logic model: A method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implementation Science 15:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01041-8.

Spencer, M. R., A. M. Miniño, and M. Warner. 2022. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2001–2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db457.pdf (accessed December 30, 2024).

Stelmach, R., E. L. Kocher, I. Kataria, A. M. Jackson-Morris, S. Saxena, and R. Nugent. 2022. The global return on investment from preventing and treating adolescent mental disorders and suicide: A modelling study. BMJ Global Health 7:e007759. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckad193.

TFA (Trust for America’s Health). 2008. Prevention for a healthier America. https://www.tfah.org/wp-content/uploads/archive/reports/prevention08/Prevention08Exec.pdf (accessed December 30, 2024).

TFA. 2009. Prevention for a healthier america: Investments in disease prevention yield significant savings, stronger communities.

UWDGH (University of Washington Department of Global Health). 2024. Step 4: Select research methods. https://impsciuw.org/implementation-science/research/select-research-methods/ (accessed October 29, 2024).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2024. Constitution. https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution (accessed December 13, 2024).

Williams, R. 2024. International Comparisons & International Health, presented to the Committee on Blueprint for a National Prevention Infrastructure for Behavioral Health Disorders, Meeting 3. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42281_04-2024_blueprint-for-a-national-prevention-infrastructure-for-behavioral-health-disorders-meeting-3 (accessed December 16, 2024).

Zilkha, C., V. Agarwal, and R. G. Frank. 2024. Suicide rates are high and rising among older adults in the US. Health Affairs Forefront. https://doi.org/10.1377/forefront.20240228.27143.