State DOT Certification Programs for Materials Sampling and Testing Personnel (2025)

Chapter: 2 Literature Review

CHAPTER 2

Literature Review

The literature review presented in this chapter describes the DOT certification programs and how they were developed in different ways, in part due to the flexibility found in 23 CFR 637B. Included is a brief history of the requirements DOT sampling and testing technician personnel must meet and a discussion of the current guidelines and standards for technician certification.

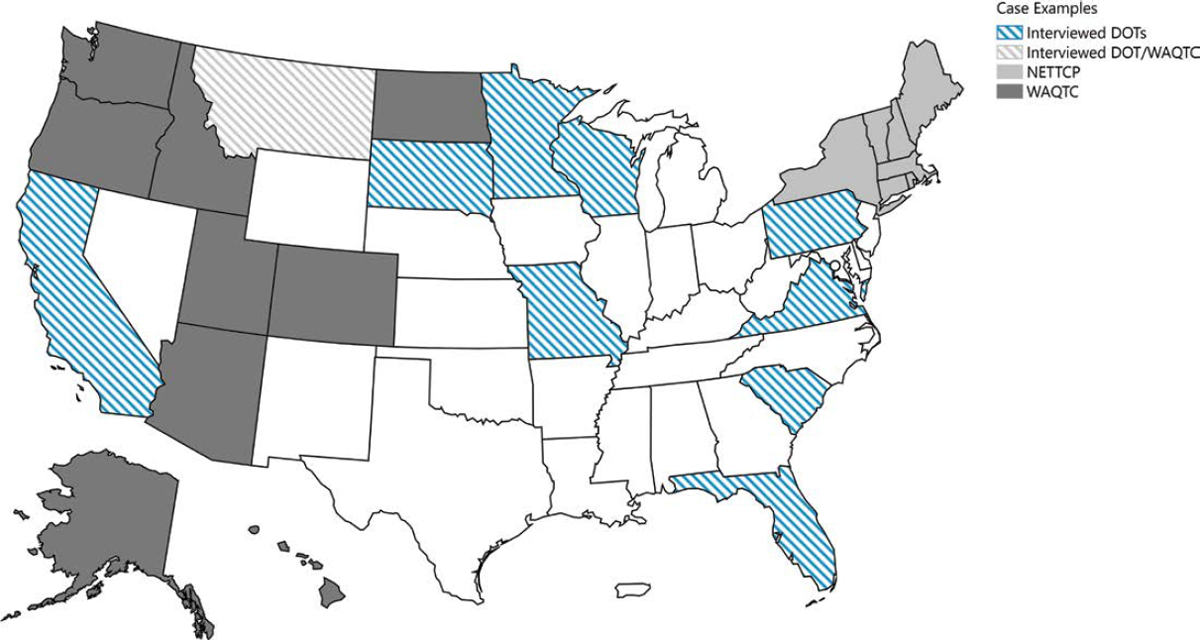

The literature review further describes the current AASHTO and international standards related to technician certifications and how they affect DOT certification programs and definitions, including the terms qualified and certified. At least 35 DOTs are connected to a certification-related cooperative effort. These cooperative efforts were developed in response to the 23 CFR 637B personnel requirements. The history and activities of the cooperative efforts are described, and the DOTs involved are listed.

DOTs also use a variety of external and internal certification programs. The external programs related to the literature review are described in detail in Appendix E; highlights are included in this chapter. DOTs also incorporate national training materials into their certification programs, which are also described in this chapter.

History, Guidelines, and Standards

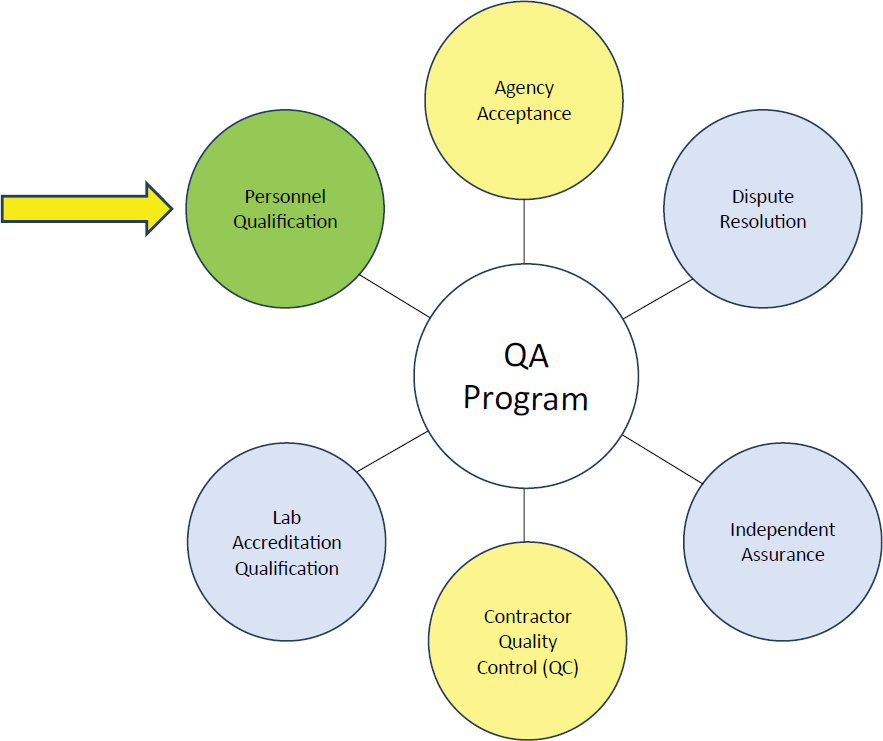

Six core elements of a construction QA program included in the current 23 CFR 637B (shown in Figure 1) include agency acceptance, contractor quality control (QC), IA, personnel qualification and certification, laboratory accreditation and qualification, and material testing dispute resolution.

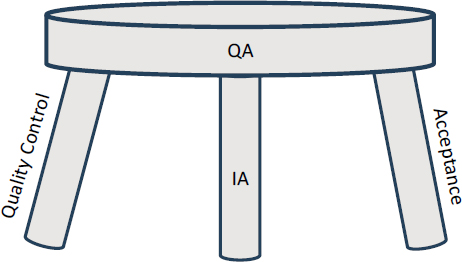

DOT certification programs for personnel who conduct materials sampling and testing are the backbone of the personnel qualification element of QA. Sampling and testing qualification requirements were added to 23 CFR 637B in 1995 (National Archives and Records Administration 1995). Before then, QA was often described as a three-legged stool (Figure 2) consisting of contractor QC, IA, and agency acceptance. Although not one of the original legs, both technician certification and laboratory certification were recognized as part of a total quality management program, and joint training of contractors and DOT sampling and testing personnel was encouraged (Burati and Hughes 1993).

Although qualified technicians were not added to the 23 CFR 637B definition of core elements of a QA program until 1995, evidence of certification of technicians has been found that precedes those requirements. In 1965, the West Virginia DOT developed a certification program for bituminous concrete technicians (Steele and Higgins 1981), and West Virginia recognizes this long history on their current technician certification website (WVDOH 2024). After 1995, all DOTs developed some type of qualification or certification program for their sampling and

Source: Reproduced and modified from Dvorak and Conway 2023

Source: Reproduced based on Burati and Hughes 1993

testing personnel. Although 23 CFR 637B used the term qualified, it was generally “interpreted to mean that most paving technicians must be certified . . .” as noted in a 1998 symposium paper (Christensen et al. 1999).

History of the CFR

As far back as 1938, 23 CFR required materials used in highway construction to be tested prior to use. The interstate era and the growth in funding and construction caused additional changes in the CFR. The Sampling and Testing of Materials and Construction section of 23 CFR 637B that discusses acceptance testing, IA, and project materials certification was added in 1975 (National Archives and Record Administration 1975). After 1975, the industry increased the use of QC/QA specifications. QC/QA specifications are specifications that define the quality control testing that the supplier, the contractor, or both are to perform to achieve the results that the DOTs require. The material quality is verified through testing by the DOT and accepted if standards are met. QC/QA specifications use statistical sampling and pay factors—based on performance-related properties—to accept materials incorporated into the project. Before the development of QC/QA specifications, many DOTs used method specifications that spelled out what materials to use and how to incorporate them (Burati and Hughes 1993). Currently, the term quality assurance specifications is used to describe specifications that include both contractor QC and agency acceptance (TRB 2018). Before QA specifications were adopted, DOTs performed all materials testing on a project, including QC. QA specifications shifted the QC testing to producers and contractors. DOTs use random sampling and testing to assure the quality of materials.

Along with addressing the qualification of sampling and testing personnel and of laboratories, the 1995 CFR introduced the use of contractor test results in the acceptance decision. This allowed DOTs to use contractor test results if they are validated by the DOT. Contractor test results may be different from DOT test results; although variability is inherent in materials, one aspect of test result variability can be the sampling and testing. The technicians’ ability to reliably perform the sampling and testing became more apparent through the use and comparison of contractor test results. At the same time, Superpave research was developing new test methods for asphalt pavement materials that involved new procedures (West and Lynn 1999), and the precision of those new procedures could be affected by testing variability. This all led to a heightened awareness of the importance of properly training and evaluating sampling and testing technicians.

The CFR revisions in 1995 allowed 2 years (until 1997) for the DOTs’ main labs to be qualified (i.e., accredited) and allowed DOTs until June 2000 to address the development of qualifications for sampling and testing personnel. The original wording in the 1994 version of the CFR used the term certified to define qualified sampling and testing personnel (technicians) but, in response to two comments received during the public comment period, the wording to describe qualified technicians was changed from certified to capable (Hughes 2005).

The current 23 CFR 637B specifically addresses all six core QA components. It defines qualified sampling and testing personnel as “Personnel who are capable as defined by appropriate programs established by each STD.” (U.S. Government Publishing Office 2024). As used in this code, STD stands for “state transportation department” and is synonymous with the term DOT. When the regulation was originally issued, no other guidelines existed. In 1998, FHWA provided guidelines on the elements that should be included in a qualification program for sampling and testing personnel. These will be discussed more in the next section.

Currently, 23 CFR 637B is titled Quality Assurance Procedures for Construction; the full text can be found in Appendix D.

Current Guidelines Related to Technician Certification

Currently, 23 CFR 637B requires that all technicians and laboratories used in the acceptance program be qualified and that the main DOT laboratories be accredited. Additional FHWA guidelines specifically related to QA can be found on two websites (see Appendix D for complete text) and include the following components related to sampling and testing personnel:

- Materials: Clarifies that 23 CFR 637B is intended to cover soils, aggregates, asphalt materials, and Portland cement concrete (PCC)—also referenced simply as concrete

- Training materials for technicians: Encourages the use of AASHTO Technical Training Solutions (formerly Transportation Curriculum Coordination Council or TC3) for training materials

- Sampling and testing personnel: Encourages use of IA as part of evaluation

- Qualification program elements: Specifically recommends that sampling and testing (including laboratory and field) personnel’s qualification programs should include:

- Formal training

- Hands-on (proficiency) training

- A period of on-the-job training under a qualified technician

- Written exam and demonstration of proficiency (performance exam) in sampling and test methods

- Requalification at 3- to 5-year intervals

- Documented processes for retraining or removing technicians

FHWA has been performing process reviews on DOTs’ QA programs every few years since 2003 (FHWA 2021). A national review published in 2007 provided several recommendations, including the need for a QA Manual of Practice and a question-based evaluation tool to evaluate DOT QA programs (FHWA 2007). Such an evaluation tool was developed and has been used in assessments conducted since 2008. Two questions in the last FHWA QA review summary document are related to technicians and the criteria used to qualify technicians. The questions are summarized as follows:

- Does the IA program that reviews technicians performing testing cover a minimum percentage of the technicians yearly? (90 percent noted as the goal).

- Does the DOT sampling and testing technicians’ program for the areas of asphalt pavement, concrete, and soils and aggregate include the following?

- Formal classroom training on sampling and testing procedures

- Written examination

- Demonstration of testing proficiency (performance exam)

- Requalification procedures

- Documented decertification process for retraining or removing personnel (Grogg and Espinoza-Luque 2023)

The questions follow the guidelines noted previously and included in Appendix D.

Guidelines in AASHTO Standards

The AASHTO COMP, as a group, manages over 500 AASHTO Materials Standards that cover all aspects of materials and the construction of materials for DOTs. The AASHTO COMP Technical Subcommittee (TS) 5c, Quality Assurance and Environmental, is responsible for standards related to technician certification and other QA components. Two of these AASHTO standard practices, which provide guidelines on technician certification or training, are as follows:

- AASHTO R 18: Standard Practice for Establishing and Implementing a Quality Management System for Construction Materials Testing Laboratories

- AASHTO R 25: Standard Practice for Technician Training and Certification Programs

AASHTO R 25 is directly relevant to sampling and testing technician certification; AASHTO R 18 is related to laboratory testing technicians.

AASHTO R 25: Standard Practice for Technician Training and Certification Programs, includes recommendations related to the following areas:

- Organization and management of the certification program

- Training and certification policies

- Training programs

- Examination methods

- Certification

AASHTO R 25 provides guidelines; it contains mainly “should” (and very few “must”) statements. The “must” statements in AASHTO R 25 include the following:

- Testing must be realistic and practical (Section 5.2).

- Program must have documented policies and procedures (Section 7.1).

- Examiners for performance exams must be qualified in the areas of the exam (Section 7.8).

- Appeals (for decertification) must be in writing (Section 7.9).

- A written policy must be maintained for certification programs (Section 8.1).

- A registry of certified technicians must be maintained (Section 8.2).

- A written policy to protect the privacy of technicians’ records must be maintained (Section 8.6).

AASHTO R 25 provides recommendations similar to the FHWA guidelines in relation to types of materials covered, encouragement to use AASHTO Technical Training Solutions materials and IA, and parameters for general training and testing. AASHTO R 25 recommends that a timeframe be established for recertification but does not indicate a duration (FHWA recommends 3 to 5 years). The standard also recommends the use of a joint oversight committee that includes industry for the certification program; this recommendation is not addressed in the FHWA guidelines. AASHTO R 25 includes an appendix that lists potential qualifying test methods in the areas of soils and aggregates, asphalt mixture, and PCC.

AASHTO R 18: Standard Practice for Establishing and Implementing a Quality Management System for Construction Materials Testing Laboratories includes guidelines related to laboratory technicians. As noted earlier, 23 CFR 637B requires each DOT to have its main laboratory accredited. The AASHTO Accreditation Program (AAP) is one laboratory accreditation program that follows the AASHTO R 18 standard requirements. AASHTO R 18 for technicians includes the following:

- Requirements that the laboratory maintain a procedure for laboratory technicians that “ensures that laboratory personnel are trained.” It also requires maintenance of training and evaluation records.

- Requirements that a proficiency (performance) evaluation of laboratory technicians be conducted for each test method performed. Frequency of these evaluations is not stipulated, but the evaluations must be set and documented by the laboratory. Such evaluations can be performed by in-house personnel, a certification program representative, an assessment body representative, or a consultant.

- Recommendation of training, which may include on-the-job training (OJT), formal in-house training for certification, or training provided by external organizations.

Per AASHTO R 18, laboratories shall maintain procedures to describe the methods used to train and evaluate laboratory technicians, but the method of training is up to the laboratory. The required procedures must include proficiency evaluations, but the method of performing the proficiency evaluation is also up to the laboratory. A proficiency or performance evaluation (or exam) entails an observation of a test being performed; it is not a written exam. Laboratory

technicians must be evaluated in their performance of test methods (through proficiency or performance exams) but do not necessarily have to take written exams or be certified to be qualified under AASHTO R 18.

The 23 CFR 637B defines some aspects of laboratory qualification and requires accreditation for the main DOT laboratory, but the definition of personnel qualifications is left up to the DOTs. FHWA and AASHTO R 25 encourage training and the use of both written and performance (proficiency) examinations for technicians. AASHTO R 18 requires evaluation of laboratory technicians through proficiency evaluations and encourages training and certification for laboratory technicians.

The CFR, FHWA, and the referenced AASHTO standard practices do not mandate training for technicians, nor do they mandate that technicians must be certified to perform acceptance testing; they do provide general guidelines on methods to ensure that qualified technicians perform sampling and testing functions. This flexibility was recognized by West and Lynn in a December 1998 symposium when they noted, “As a result, technician certification . . . programs are likely to continue to develop independently in many states.” (West and Lynn 1999).

International Standards

ASTM International (formerly known as the American Society for Testing and Materials) is a body that maintains standards that are also used by DOTs. ASTM has a standard specifically for certificate programs. ASTM E2659: Standard Practice for Certificate Programs was originally published in 2009. This standard describes the requirements for entities providing certification and differentiates certificate programs from other types of certifications. ASTM E2659-18 references American National Standards Institute (ANSI) International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission (ISO/IEC) 17024:2012, Conformity Assessment—General Requirements for Bodies Operating Certification of Persons; it indicates that ANSI 17024 is used for personnel certification programs and that ASTM E2659-18 is for certificate programs. ANSI 17024 specifically states that training and certification should be performed by separate entities, and does not address any requirements for training programs, only for certification programs. ASTM E2659-18 defines a certificate program as one in which the training and assessment are linked. In practice, the term certification program has been used to describe both a stand-alone assessment without training and training with an end-of-course assessment. ASTM also has a Construction Materials Testing (CMT) certification program, which is described in the External Certification Programs subsection of this synthesis.

ASTM has the following five additional standards that discuss or contain personnel certification requirements (none of these standards reference ASTM E2659-18):

- ASTM D3666: Standard Specification for Minimum Requirements for Agencies Testing and Inspecting Road and Paving Materials (related to asphalt mixtures)

- ASTM D3740: Standard Practice for Minimum Requirements for Agencies Engaged in Testing and/or Inspection of Soil and Rock as Used in Engineering Design and Construction (related to soils and aggregates)

- ASTM C1077: Standard Practice for Agencies Testing Concrete and Concrete Aggregates for Use in Construction and Criteria for Testing Agency Evaluation (related to concrete)

- ASTM C1093: Standard Practice for Accreditation of Testing Agencies for Masonry

- ASTM E329: Standard Specification for Agencies Engaged in Construction Inspection, Testing, or Special Inspection (related to inspection)

The ASTM standards have been driving some certification program requirements due to their use by other entities, such as the FAA. The FAA requires ASTM D3666 accreditation for laboratories that develop asphalt mixture formulas used in airport construction projects

(Johnson 2016 and FAA 2018). ASTM D3666 requires an external certification (defined as national, regional, or DOT) for laboratory supervisors, field supervisors, and lab and field technicians. Related to construction inspection, ASTM E329 requires external certifications for laboratory and field supervisors. The other ASTM standards (D3740, C1077, and C1093) require either internal or external written exams and performance evaluations for personnel. AASHTO R 18 does not require certification or even written exams, only that the lab follow its written procedures and document that it has evaluated its technicians’ proficiency in performing the tests. However, if a laboratory wants accreditation according to the ASTM standards, it is required to have certifications, potentially even external certifications. The certifications required by ASTM are defined as internal or external, with external being defined as certification programs that include a formal exam that is administered by a third party.

DOTs are required to use qualified technicians in accordance with the CFR, and DOTs can define what it means to be qualified. Guidelines exist that include using aspects of certification programs (such as training and written and performance exams) to identify qualified technicians. Certification is also required in the construction industry, driven in part by ASTM standards. There is still some confusion about the difference between qualified and certified technicians.

Qualified and Certified Technician Definitions

The definitions of “qualified” and “certified” technicians, or “qualification” and “certification,” used in the standards and by DOTs are varied. In 23 CFR 637B, only the term “qualified technician” is defined. A previous NCHRP synthesis project on construction QA programs identified that some states were prohibited by law to certify anyone but their own employees, which is why “certified” was removed (Hughes 2005).

Other than AASHTO R 18 and AASHTO R 25, the following AASHTO standard practices (also under AASHTO COMP TS 5c) all define or reference either qualified or certified technicians:

- AASHTO R 9: Acceptance Sampling Plans for Highway Construction

- AASHTO R 10: Definition of Terms Related to Quality and Statistics as Used in Highway Construction

- AASHTO R 38: Quality Assurance of Standard Manufactured Materials

- AASHTO R 42: Developing a Quality Assurance Plan for Hot Mix Asphalt (HMA)

- AASHTO R 44: Independent Assurance (IA) Programs

- AASHTO R 89: Accreditation Bodies Operating in the Fields of CMT and Inspection

Table 1 shows the definitions in these standards (in parentheses and italics or if the term is not specifically defined; a few particularly different passages are bolded) and if the standard mentions the term, how it does so. The table also includes the CFR definition, definitions from AASHTO R 18 and R 25 and the AAP Accreditation Policy on Certification.

Although these standards are all different, the definitions do not conflict with what is used by DOTs, with the exception of AASHTO R 10. AASHTO R 10 definitions consider a certified technician to be automatically qualified. As shown in the survey and website review described later in this document, DOTs may accept external certifications but have additional, state-specific requirements that must be met before they consider the technician qualified.

As shown in the survey in the next chapter, DOTs use the term “certified” more than the term “qualified” to describe their technician program.

ASTM standards do not use the term qualified, only certified. Some of the ASTM standards include a section that covers the general requirements for personnel. Personnel requirements in the ASTM standard can include external or internal certification, internal exams, a professional engineering license, or documented work experience.

Table 1. Different definitions and usage of qualified and certified.

| Source | Qualified Technician | Certified Technician |

|---|---|---|

| 23 CFR 637B | “Personnel who are capable as defined by appropriate programs established by each STD.” | Certification only found in terms of project material certification, not in relation to technicians. |

| AASHTO R 9 | Recognizes importance of having qualified technicians. | Recognizes that “some agencies require certification to determine qualification.” |

| AASHTO R 10 | “A technician who has been determined to be qualified (i.e., meeting some minimum standard) to perform specific duties. [A qualified technician may or may not be certified. See certified technician.]” | “A technician certified by some agency (or organization) as proficient in performing certain duties. [A certified technician is considered to be qualified. A qualified technician may or may not be certified. See qualified technician.]” |

| AASHTO R 18 | Not defined directly, but technicians are required to be evaluated through observation “for the tests they are qualified to perform.” | Not defined. |

| AASHTO R 25 | “The term ‘qualification’ is equivalent to ‘certification’ within this standard.” | |

| AASHTO R 38 | “…personnel who are capable as defined by appropriate programs established or recognized by each agency.” | “…personnel who are recognized by a formal certifying body as qualified to perform sampling, testing, inspection, or related procedures.” |

| AASHTO R 42 | “Sampling and testing personnel should be qualified through procedures developed by the agency…” | Certified or certification not defined in R 42. |

| AASHTO R 44 | Qualified personnel, qualified laboratories, and AASHTO R 25 are referenced, but not defined. | Certified and certification are only found in relation to certified products or certification of project material, not in relation to technicians. |

| AASHTO R 89 | “…generally refers to a process specified by a governmental body (or other authority)…” | “…generally applies to people or products.” |

| AAP Accreditation Policy on Certifications | “Approved through a review and decision-making process.” | “…holding a valid credential that recognizes the competency of the certificant through passing a formal examination.” |

Who Needs to Be Certified, What Needs to Be Tested?

The title of 23 CFR 637 is Construction Inspection and Approval and subsection 23 CFR 637B is titled Quality Assurance Procedures for Construction. The definition of an acceptance program in 23 CFR 637 includes sampling, testing, and inspection. The FHWA guidelines for qualification of construction inspection technicians are similar to the recommended procedures for qualification of sampling and testing technicians, without the performance evaluation component (See Appendix D). However, 23 CFR 637.209(b) specifically uses “sampling and testing personnel” when referring to personnel required to be qualified. Although sampling and testing technicians are recognized by DOTs as requiring some type of formal qualification or certification, inspector certifications were not as prevalent. This synthesis is focused on sampling and testing

certifications, but inspection certifications are noted where they were encountered. Recent research related to construction inspection personnel was found in the literature review and is described at the end of Chapter 2.

The practices and test methods that are to be included in a certification need to be considered by each DOT. 23 CFR 637.207(a)2 states that “the IA program shall evaluate the qualified sampling and testing personnel.” The CFR requires that those test methods included in acceptance and IA testing be performed by qualified technicians. IA is defined in 23 CFR 637.203 to include test procedures used in the acceptance program but specifically excludes the test procedures in the DOT’s central lab. More specific guidelines on which practices and test methods to include in a certification program were not found. In practice, the DOT and the local FHWA division decide (as part of the FHWA review process of a DOT’s QA program) what constitutes an acceptance test for inclusion in a certification program.

Existing DOT Cooperative Efforts

In response to the 1995 personnel qualification and certification requirements in 23 CFR 637.209, five regional training and certification groups were formed: the Mid-Atlantic Region Technician Certification Program (MARTCP), the North Central Multi-Regional Training and Certification Program (M-TRAC), the Northeast Transportation Technician Certification Program (NETTCP), the Southeast Task Force for Technician Training and Qualification (SETFTTQ), and the Western Alliance for Quality Transportation Construction (WAQTC) (FHWA 1999). Of those listed, only SETFTTQ is no longer found in the literature.

Figure 3 shows the states identified as participating in a cooperative certification effort. Two of the DOTs were identified as participating in more than one cooperative effort.

MARTCP

The Mid-Atlantic Region Technician Certification Program’s May 2023 Training and Testing Information document includes the logos of the Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia DOTs (MARTCP 2023). The MARTCP website (MARTCP, n.d.) is maintained by the Maryland State Highway Administration (SHA) Office of Materials Technology, Materials Management Division. MARTCP provides training and certification for technicians performing QC and QA testing. The website review completed as part of this synthesis noted that MARTCP certifications were mentioned in the District of Columbia, Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania DOT websites. Recent Virginia DOT documents state that VDOT does not have reciprocity with MARTCP certifications (VDOT 2024). However, the DOTs listed are all identified as participating in the Mid-Atlantic Quality Assurance Workshop. That QA Workshop has been held annually since 1967 as a 3-day event and includes discussions on materials and quality assurance.

M-TRAC

Multi-Regional Training and Certification is a training partnership and an affiliate of AASHTO Technical Training Solutions (M-TRAC, n.d.). M-TRAC provides a forum for DOTs to share information in order to maximize resources. Its member DOTs are those of Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Texas, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Des Moines Area Community College currently supports M-TRAC. Previously, it was supported by the North Central Superpave Center at Purdue. During the early development of Superpave (while M-TRAC was at Purdue) it developed training materials for Superpave. Some DOTs currently use training materials that began with this early cooperative effort.

M-TRAC members host a yearly meeting to discuss issues related to training and certification. FHWA assisted in organizing the first M-TRAC meeting, which was held in White Bear Lake, Minnesota, in 1996. Topics at the 2023 meeting included performance exams, online testing, how DOTs addressed cheating on exams, and changes in DOTs’ programs. The meeting also included updates from AASHTO Technical Training Solutions and FHWA. From the beginning, M-TRAC has encouraged the use of AASHTO standards and has improved the standards themselves to make it easier to attain reciprocity. For the past 5 or 6 years, an M-TRAC State Certification Programs book has been maintained that identifies the certifications used by the different states and what test methods are included in the certification programs. That book is updated regularly, and DOTs use it to determine whether certification by another M-TRAC DOT covers similar test methods. M-TRAC, in conjunction with FHWA, also developed training courses in the late 1990s in areas such as soils and asphalt. The 1998 soils training document (Cryer and Jones 1998) was found on a DOT’s certification website as a soils reference. Another DOT noted that it used the original M-TRAC training on asphalt to develop the training for their DOT’s certification program.

NETTCP

The Northeast Transportation Training and Certification Program was originally founded in 1995 as the New England Transportation Technician Certification Program. The name was changed in 2008 when the New York DOT joined the state DOTs already in the program—those of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. The NETTCP website (NETTCP, n.d.) notes that FHWA and the FAA were founding sponsors, along with several associations, material supply companies, and contractors.

NETTCP currently has nine committees, six of which are certification related. Those committees are Asphalt Plant Technician, Concrete, Geotechnical, Soils and Aggregate, Paving Inspector, and Quality Assurance Technologist. NETTCP also has a Laboratory Committee as well as a Laboratory Qualification Program, which is set up to meet the CFR requirements for qualification of laboratories. Its other committees are an Executive Committee and a Scholarship Committee.

NETTCP allows private firms to become members at various levels. Members receive a discount on technician certification courses. Over 50 corporate members were identified for the 2023–2024 term.

The 12 certifications associated with NETTCP are listed in Appendix F.

WAQTC

The Western Alliance for Quality Transportation Construction includes the DOTs of Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Central and Western Federal Lands among its membership.

The WAQTC was established in 1998 and provides training materials and a common certification platform (WAQTC, n.d.). WAQTC member DOTs observe varying degrees of reciprocity. To assist reciprocity, WAQTC DOT representatives meet annually to revise and update the training materials, which are based on AASHTO standards. WAQTC technicians are certified to perform sampling and testing according to each AASHTO standard listed in the module. The WAQTC Field Operating Procedure or the AASHTO standard are referenced by the DOTs’ specifications. Member DOTs are allowed to add agency-specific requirements but are not allowed to eliminate any portion of the WAQTC modules for a certification.

WAQTC currently includes eight certifications, which are listed in Appendix F.

Comparison of Cooperative Efforts

As with DOTs, the cooperative efforts described use different means to achieve the same goal. M-TRAC and MARTCP are voluntary; they share and coordinate efforts but do not appear to involve any joint funding for certification programs. NETTCP and WAQTC are more formal organizations. A comparison of the program management and means that NETTCP and WAQTC use to ensure qualified sampling and testing personnel are discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

External Certification Programs

A recent National Academies of Sciences document on the future needs of a skilled technical workforce estimated that there are over 4,000 certification entities in the United States (NASEM 2017). These most likely include a much larger number of individual certification programs. The certification programs considered cover a vast range of industries, including health care, computers, production, and construction. Focusing on only the highway construction industry, AASHTO re:source (https://aashtoresource.org/) has identified over 55 certification programs; many of these are DOT programs. Considering the DOT programs as internal, related external sampling and testing technician certification entities, most of which are referenced by DOTs, are the following:

- American Concrete Institute (ACI)

- Asphalt Institute (AI)

- American Concrete Pipe Association (ACPA)

- American Society for Quality (ASQ)

- ASTM International

- National Center for Asphalt Technology (NCAT)

- National Institute for Certification in Engineering Technologies (NICET)

- National Ready Mixed Concrete Association (NRMCA)

- National Precast Concrete Association (NPCA)

- Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (PCI)

- Washington Area Council of Engineering Laboratories (WACEL)

These are each individually described further in Appendix E with their relevant certifications; this section focuses only on the most pertinent highlights. Specific external certifications are also described in Chapters 5 and 6.

- ACI’s program was found to be one of the most widely used external certification programs by DOTs; only three of the DOTs identified in the survey do not formally recognize ACI certifications in some way. As described in Appendix E, ACI has 30 different certifications, but the Concrete Field Technician (ACI-CFT Grade 1), which covers the basic fresh concrete test methods (slump, air content, density, and casting cylinders), is the certification most often referenced by DOTs. ACI has 5-year recertification requirements for its ACI-CFT Grade 1 and its ACI Concrete Strength Testing Technician (ACI-CST Grade 1), the certifications most frequently used by DOTs. There are ACI chapters in over 40 states, and they have over 120 sponsoring groups that have testing centers to administer ACI exams. DOTs can be approved to administer ACI certification programs, and three DOTs are noted on the ACI website as ACI testing centers. The ACI certifications most used by DOTs focus on performance of test methods. ACI does not have a defined process to decertify technicians.

- AI has certifications for asphalt binder and emulsion that are noted as national; the increased use of these certifications was evident, but the certifications were not recognized by all DOTs. NETTCP’s PG Binder class and AI Binder class use the same training materials.

- ASTM has CMT programs in the areas of soils, asphalt aggregates, and asphalt mixture. The ASTM certifications are online exams. Some exams may include live virtual training, but most of the online training is not directly connected to the certifications. Performance (proficiency) exams are completed by the applicant’s supervisor and submitted to ASTM. ASTM certifications were not referenced on any of the DOT websites and documents reviewed but are included here because many DOTs reference ASTM standards. The certifications are designed to meet the ASTM requirements for technician certification.

- NCAT has generic certifications for asphalt mixtures, asphalt binder, and inertial profilers. NCAT was also found to host some of Alabama DOT’s and Puerto Rico DOT’s technician certifications.

- An NCHRP synthesis published in 1998 found that training requirements for materials and construction acceptance personnel were “predominately defined in terms of NICET examination qualifications” (Smith 1998). NICET has historically been linked with the 1990s quality movement related to DOTs (Farouki et al. 1999), but identification of current references to NICET certifications in DOTs’ technician certification documentation was limited. Seven DOTs identified some uses of NICET in the survey. NICET lists seven states as users in the Highway Construction realm on their website (NICET, n.d.), but only one of those DOTs responded affirmatively as being a user when surveyed. NICET Level IV certification was found as an option for the requirement of a Professional Engineer license for resident or project engineers in Connecticut. NICET was also mentioned as being related to inspector certifications (in Idaho and Ohio) and has been identified as an option in certain aspects of technician certification programs (in Arizona for field concrete supervisor, in Virginia for concrete certification). In 2019, NICET added an optional performance exam component to their existing CMT certifications in soils, asphalt, and concrete (the exam previously consisted only of written components).

- PCI certifications include three levels of plant QC technician certifications and two auditor certifications. All three levels of PCI plant certifications require ACI-CFT Grade 1 as a prerequisite.

National Efforts

Technician Training (Not Associated with a Certification)

Several DOTs referenced the training programs of FHWA and AASHTO on their websites or in documentation [the FHWA National Highway Institute (NHI) and the AASHTO Technical Training Solutions]. NHI classes were noted more for inspector-focused training, and AASHTO Technical Training Solutions were noted more for AASHTO Standard Practices and Test Methods.

The NHI is part of FHWA’s Office of Technical Services and includes the following elements:

- NHI has in-person and online training classes (web conference for live online courses; web-based for self-paced courses). The courses cover a variety of topics including planning, design, construction, maintenance, safety, and administration. The NHI Course Catalog identifies 18 different focus areas. Four areas related to material sampling and testing include (1) Pavement and Materials, (2) Geotechnical, (3) Construction and Maintenance, and (4) Structures. Most of the classes are offered in person.

- NHI encourages active learning and end-of-course assessments (exams). The classes may provide continuing education units (CEUs) but are not certification classes.

- NHI classes in the materials area include general QA training (NHI-131141: Quality Assurance for Highway Construction Projects) and more specific materials training (e.g., NHI-1311117: Basic Materials for Highway and Structure Construction and Maintenance, NHI-131135: Aggregate Sampling Basics, NHI-131139: Constructing and Inspecting Asphalt Pavements, and NHI-134097: Fresh Concrete Properties). Over 45 classes are included in the latest NHI catalog under Materials and Pavements, and over 100 different classes are included under Construction and Maintenance. The NHI classes can vary from 1-hour web-based training to multiday in-person classes.

AASHTO Technical Training Solutions is an AASHTO Technical Service Program supported by AASHTO members. It includes training on more than 20 AASHTO standards and over 100 online training courses related to materials; general information includes the following:

- The training is online and can be purchased through the AASHTO store.

- AASHTO Technical Training Solutions include videos that go through many AASHTO Standard Practices and Test Methods step-by-step.

- AASHTO Technical Training Solutions can be connected to a DOT’s learning management system (LMS) for online training for employees.

Research and Quality Assurance

The TRB Standing Committee on Quality Assurance Management (AKC30) is an active part of the QA community and has historically involved state DOT materials engineers. The committee has developed several e-circulars related to QA and research need statements related to QA. It also maintains a Glossary of Transportation Construction Quality Assurance Terms (TRB 2018) that is similar to the AASHTO R 10 Glossary.

This synthesis was a direct result of the efforts of TRB Standing Committee on Quality Assurance Management (AKC30) members; the original idea was documented in the committee’s 2023 meeting minutes. Hughes (2005) also shares a connection, that synthesis (NCHRP Synthesis 346: State Construction Quality Assurance Programs) was performed by a former chair of AKC30. That

synthesis, along with NCHRP Synthesis 263: State DOT Management Techniques for Materials and Construction Acceptance (Smith 1998), were the only synthesis projects found that were related to the topic of this one. These previous syntheses covered QA in more general terms but mentioned technician certification. Hughes (2005) includes an appendix (Appendix D) that contains an FHWA Technician Qualification memorandum dated July 17, 1998. Although the memorandum is similar to current guidelines, it notes that requalification was recommended to be performed in 2- to 3-year intervals, instead of the 3- to 5-year intervals currently recommended. These syntheses identified that the QA programs were varied.

More recent research specifically related to sampling and testing technician certification was not found, but an NCHRP research project focused on construction inspectors addressed some components of certification as related to construction inspection. Two documents were developed from that research effort: NCHRP Web-Only Document 337: Training and Certification of Construction Inspectors for Transportation Infrastructure (Harper et al. 2022) and NCHRP Research Report 1027: Guide to Recruiting, Developing, and Retaining Transportation Infrastructure Construction Inspectors (Harper et al. 2023). The research identified that construction inspection training was commonly performed using internal DOT training programs and indicated that a combination of internal and external training was the most effective. ACI, NCAT, NICET, and PCI were listed as external training or certification programs related to materials and used for construction inspectors in all four AASHTO regions.

Literature Review Summary

23 CFR 637B requires each DOT to have a QA program that addresses the qualifications of the sampling and testing technicians involved in material acceptance. AASHTO R 18 and R 25 both address testing technician qualifications. Neither standard requires technicians to be certified, nor do they require a formal written exam for testing technicians. However, AASHTO R 18 recommends training and requires a proficiency (performance) exam for laboratory technicians, and AASHTO R 25 recommends technician certification that includes training and formal written and performance (proficiency) exams. The CFR allows DOTs to define all qualifications for sampling and test technicians as well as most qualifications for laboratories, as defined in AASHTO R 18 Section 5.5, Laboratory Test Technicians. FHWA has provided additional guidelines and works with DOTs on implementing them.

ASTM standards related to soils, aggregates, asphalt mixtures, and concrete require sampling and testing personnel certifications. DOTs can specify either ASTM standards or AASHTO standards.

AASHTO standards are somewhat consistent in how they define the terms qualified and certified (if they are defined) with the exception of AASHTO R 10, which conflicts with the way most DOTs are using the terms.

Several different DOT cooperative efforts exist to reduce some of the burden of duplication or to provide examples of ways to cope with changes. These programs are very different in how they work. Two of them are discussed further in Chapter 4. External certifications are also used by DOTs in different ways. ACI concrete certification is the main external certification used by DOTs; nine other external certification programs are in use in some way by DOTs.

National-level training efforts like FHWA’s NHI and AASHTO’s Technical Training Solutions are available for training classes and training materials that can be used in a certification program. TRB’s Standing Committee on Quality Assurance Management is a focal point for national research efforts in QA.