State DOT Certification Programs for Materials Sampling and Testing Personnel (2025)

Chapter: 5 DOT Certification Program Findings

CHAPTER 5

DOT Certification Program Findings

As part of gathering material for this synthesis, each DOT website was reviewed for information on its certification program. The review included DOT websites, linked websites of outside entities (such as colleges or associations), program manuals, pamphlets, and training manuals. In the survey, 41 DOTs provided website links for their certification programs. Four DOTs provided one or more documents in response to the survey question.

The case examples in Chapter 4 provide some specific information, based on interviews, related to overall program management and use of technology for 10 different DOT programs. This chapter consolidates the findings from the survey, case examples, and DOT website review and presents them in a format that covers the components of a certification program as documented in AASHTO R 25, Standard Practice for Technician Training and Certification Programs.

AASHTO R 25 is specifically related to the practices used in certification programs and associated training. The standard consists of the following five sections:

- Program organizational structure

- Training and certification policies (including prerequisites and reciprocity)

- Training (including online training)

- Examinations and methods

- Certification (including recertification and decertification)

AASHTO R 25 guidelines related to each of the sections is also noted where appropriate.

Program Organizational Structure

The case examples on program management in Chapter 4 provided examples of how DOT certification programs were organized in different ways. It also provided examples of the different organizational structures of the two cooperatives, NETTCP and WAQTC. Table 24 illustrates program management combinations described in response to survey Question 6. The numbers in the table reflect the number of DOTs that identified the listed combination of entities as related to program management for a particular material (soil, aggregate, asphalt, or concrete). The table shows that there were 13 different program management structure combinations identified in the survey, with those for asphalt having the most variations. The DOT is the predominate selection for each of the materials. All 52 DOTs surveyed responded to Question 6. Seventeen DOTs (33 percent) selected DOT only for all four of materials (those of Alaska, Arkansas, California, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, South Dakota, Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming). Fifteen DOTs (29 percent) also identified a consistent program management structure for each of the materials (those of Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts,

Table 24. Combinations of program management entities/structure (compiled from survey Question 6).

| Program Management* | Soils | Aggregate | Asphalt Mixture | Concrete | |

| DOT only | 26 | 22 | 19 | 19 | of 52 DOTs |

| 50% | 42% | 37% | 37% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT and outside C/C | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | of 52 DOTs |

| 8% | 6% | 8% | 6% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT and C/U | 6 | 8 | 9 | 5 | of 52 DOTs |

| 12% | 15% | 17% | 10% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT and OA | 6 | 7 | 6 | 10 | of 52 DOTs |

| 12% | 13% | 12% | 19% | % of DOTs | |

| C/C only | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | of 52 DOTs |

| 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | % of DOTs | |

| C/U only | 2 | 1 | of 52 DOTs | ||

| 0% | 0% | 4% | 2% | % of DOTs | |

| OA only | 3 | 6 | 6 | 3 | of 52 DOTs |

| 6% | 12% | 12% | 6% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT, C/C, and C/U | 2 | 1 | 1 | of 52 DOTs | |

| 4% | 2% | 2% | 0% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT, C/C, and OA | 1 | of 52 DOTs | |||

| 0% | 0% | 2% | 0% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT, C/C, C/U, and OA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | of 52 DOTs |

| 2% | 2% | 2% | 6% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT and LTAP | 1 | 1 | of 52 DOTs | ||

| 2% | 2% | 0% | 0% | % of DOTs | |

| LTAP and OA | 1 | of 52 DOTs | |||

| 0% | 0% | 2% | 0% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT, C/U, and OA | 1 | 1 | of 52 DOTs | ||

| 0% | 0% | 2% | 2% | % of DOTs | |

| None noted | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | of 52 DOTs |

| 4% | 2% | 0% | 0% | % of DOTs |

* Abbreviation key:

C/C = Contractor/consultant

C/U = College/university

LTAP = Local Technical Assistance Program

OA = Outside association

Missouri, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, and Vermont). The remaining 20 DOTs (38 percent) noted variations in the program management structure by material. DOT programs not only differ from each other, but may also vary by material within a single DOT.

AASHTO R 25 Sections 4.1 and 4.2 recommend that DOTs partner with other parties that are involved in the technician certification program, including the development of a certification oversight committee and the use of task groups for each certification area. Caltrans’s Advisory Council and MnDOT’s Technical Certification Advisory Committee, described in Chapter 4, are examples of oversight committees that include partners. FDOT’s TRTs and SCDOT’s task forces, also described in Chapter 4, are examples of task groups.

AASHTO R 25 also describes different options for leading the program, including in-house, consultant, universities/colleges, public/private, and national organizations. Although these are described individually in AASHTO R 25, they can also be used in combinations, as shown in the survey results and in Table 24. One example of using combinations of partners was found in the Colorado DOT (CDOT)’s documentation.

CDOT notes a variety of allies in its certification program, including ACI, LabCAT (Laboratory for Certification of Asphalt Technicians, a certification program administered by the Rocky Mountain Asphalt Education Center), and WAQTC. CDOT’s Field Materials Manual 2024, which is over 900 pages long, contains all of the CDOT test procedures and includes Colorado Procedure (CP) 10-24, Standard Practice for Qualification of Testing Personnel and Laboratories. CP 10-24, Table 10-1 (Sampling and Testing Personnel Qualifications) clearly identifies the associated AASHTO, ASTM, and CDOT designation for test methods, as well as which certification is required to perform the test. Several types of ACI certifications are used for the concrete and aggregate tests; LabCAT certifications are used for asphalt mixture and asphalt aggregate testing, and WAQTC is used for embankment and base.

Training and Certification Policies

For standard practices and test methods, AASHTO R 25 Section 5.1 recommends the use of AASHTO practices and test methods if possible. Pennsylvania DOT (PennDOT)’s Field and Laboratory Testing Manual (Publication 19) indicates there have been 40 Pennsylvania Test Methods deleted since 2013 as PennDOT adopts AASHTO standards. The prevalence of DOT-specific methods is evident in the certification programs noted in Appendix F. Even with DOTs that predominately use AASHTO standards, there may be DOT modifications. AASHTO R 25 recommends the use of standard methods to make it easier for programs to be developed regionally or nationally. As discussed in Chapter 6, there are reasons that some practices and methods may need to be customized based on local conditions.

Prerequisites

AASHTO R 25 Section 5.4 addresses the use of prerequisites, such as experience or required training. In the case examples in Chapter 4, it was shown that NETTCP certifications used prerequisites; they expect the technicians to have experience before taking the certification classes and exams, whereas the WAQTC training materials are structured toward newer technicians.

This difference in certification and training program focus was also seen in the individual DOTs. In some DOT certification programs, training appeared to be designed for newer technicians. Tests are demonstrated in the lab, and technicians can practice running the tests in the lab before taking the certification exams. These programs may also have a separate, shorter recertification class that is designed for more experienced technicians. Some certifications specifically require experience. The test methods may be described in class, and the technician is expected to know how to perform the test before attending class. Thirteen DOTs (not including the seven NETTCP DOTs) were found to specifically require or recommend prior experience for at least some of their certifications (those of Arizona, Colorado, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming). Recent changes related to experience requirements were found in the Arizona DOT (AzDOT).

AzDOT’s Arizona Technical Testing Institute (ATTI) program recommended that technicians have experience in the test methods but now requires a minimum of 12 months of experience or its equivalent. In 1995, AzDOT and industry formed a steering committee to address sampling

and testing requirements. ATTI is a nonprofit organization that was created the following year. The program is governed by a Board of Directors composed of AzDOT representatives, contractors, consultants, materials suppliers, and a technical advisory board. ATTI offers three certifications: Field Technician (for general field sampling and testing), Laboratory Soils/Aggregate Technician, and Asphalt Technician (for lab testing of asphalt mixtures). ACI-CFT Grade 1 is accepted by AzDOT for concrete field testing.

The ATTI website noted that in the previous year, the process was amended to require proof of prior experience before technicians can take the certification classes and exam. This information appeared in the following pop-up on the ATTI home page:

We wanted to inform you of some upcoming changes to ATTI in 2023 . . . The ATTI program is designed such that applicants must have experience or have received training in the applicable test methods and calculations before taking examinations.

Therefore, the ATTI Board of Directors voted to implement the following prerequisites . . . All New Applicants . . . must submit evidence of this training or experience in one of the following ways:

- work history . . . 12 months experience . . .

- record of prior certification . . .

- training records demonstrating initial training in each of the test methods . . .

The training records must be verified by a qualified person . . . (ATTI 2023)

ATTI does have a recertification class, and it reintroduced the recertification review class and is steering technicians to the ATTI study guides and videos in order to ensure that the technicians are prepared for the exams.

Differing laboratory, field technician, and inspector requirements were found on the Oregon DOT (ODOT) website, with separate links for technician, inspector, and laboratory certifications (ODOT, n.d.). ODOT is a member of WAQTC and coordinates with the Asphalt Pavement Association of Oregon, Oregon Concrete and Aggregates Producers Association, and the Oregon Chapter of the ACI for technician certifications. The Inspector Certification Program is operated in-house, and the program document states that it is a part of ODOT’s overall QA program. All inspectors are required to have the General Construction Inspection certification. The laboratory certification program reviews the laboratory and lab equipment.

Reciprocity

AASHTO R 25 Section 5.3.2 recommends that DOTs have a written policy regarding reciprocity. AASHTO R 25 also recommends that the requirements for certifications (such as training, prerequisites, and exams) should be identified.

Reciprocity in this context means accepting another DOT’s certification program as a partial or complete alternative to a DOT’s own certification, or an agreement that a certification is joint (i.e., reciprocity is mutual). Reciprocity can also mean accepting another certification, such as ACI or NICET. In the survey, 49 of 52 DOTs indicated that they accepted or required ACI certification. Other forms of reciprocity for other materials testing areas included the following:

- Case-by-case basis of acceptance

- DOT-specific exam and other certification information required

- Specific certifications identified as reciprocal

The following section includes examples of written reciprocity policies found on the DOT websites or in the technician certification policy documents.

Iowa DOT

The Iowa DOT accepts certifications from other DOTs if all criteria in the Iowa DOT Technical Training and Certification Program Information and Registration Booklet (Instructional Memorandum 213) are met. The booklet also notes that if the DOT certification is considered to be similar, the applicant can take the Iowa DOT exam without attending the full certification class, but a passing exam is still required for certification. The Iowa DOT recognizes the ACI certifications, but applicants need to take a web-based PCC Level I review that covers elements that are not in the ACI exams (maturity, flowable mortar, beams, and measuring cores) and pass a written exam in order to receive the PCC certification.

Kansas DOT

The Kansas DOT Policy and Procedure Manual for The Certified Inspection and Testing Training (CIT) Program notes that the Kansas DOT accepts recent aggregate and Superpave certifications from the Iowa, Nebraska, and Missouri DOTs if the applicant passes the basic math exam and successfully performs the sampling and testing procedures, witnessed by DOT personnel. These DOTs also recognize ACI-CFT Grade 1.

Maryland DOT

The Maryland DOT has an Accepted Reciprocity List document linked on its website (MARTCP, n.d.) that includes which certifications are accepted, not accepted, or not applicable, as well as reciprocity conditions for the Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia DOTs, ACI, WACEL, and 3RD PAGES.

Minnesota DOT

The Minnesota DOT (MnDOT) has an online State Reciprocity Certification Exam option. Its certification program web page (MnDOT, n.d.-a.) includes the requirements and how to apply for the reciprocity exam. Some of the requirements are that the other DOT certification is current, that there is a valid reason that the latest MnDOT certification class (held between November and May) was missed, that the certification is comparable, and that the technician has experience. The reciprocity exam is the full certification exam, and the student is provided with the option to self-study and take the exam without attending the class. Students are not allowed to retest; if they fail the exam they must attend the full certification class.

Missouri DOT

The Missouri DOT (MoDOT)’s Technician Certification Program Policy notes that other DOTs may recognize MoDOT’s certifications and that MoDOT may recognize those of other DOTs. The Technician Certification Coordinator will make the determination on a case-by-case basis. MoDOT includes its certifications in the M-TRAC book of certifications described in Chapter 2 and has used the M-TRAC book itself to aid in determining whether to accept other DOTs certifications.

North Dakota DOT

The North Dakota DOT addresses reciprocity in its online Technical Certification Program FAQs (NDDOT, n.d.). Reciprocity requires that applicants pass the written exam with a score of at least 70 percent, as well as pass a performance exam. The other DOT’s certification must be valid, and it will be verified. Reciprocity is good for 1 year; the applicant must take the full certification class to receive full certification. The North Dakota DOT recognizes the ACI-CFT Grade 1 as equivalent, with no additional testing required.

South Carolina DOT

The South Carolina DOT (SCDOT) recognizes that “Acceptance of SCDOT Certification by other state agencies is at the sole discretion of the other agency” (SCDOT 2024). The guidelines also consider reciprocity of other agencies’ certifications as special circumstances; only the class portion will be waived, and passing the SCDOT exam is still required.

Utah DOT

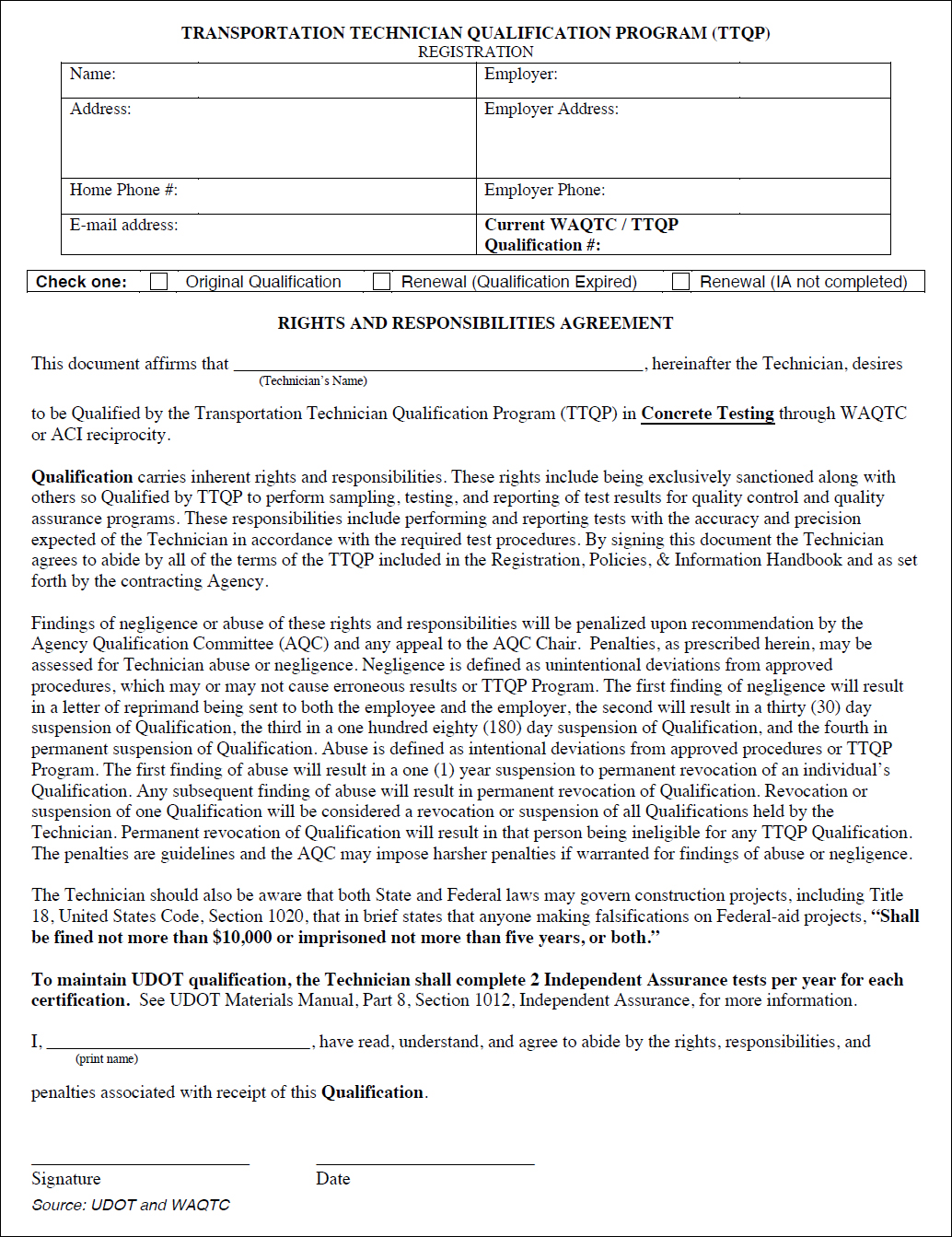

The Utah DOT (UDOT) is a member of WAQTC. UDOT specifically addresses WAQTC reciprocity, along with ACI reciprocity, on its website (UDOT, n.d.-a). Applicants must sign a Rights and Responsibilities Agreement (Figure 26) and must participate in the UDOT IA program for an ACI certification to be accepted instead of a UDOT WAQTC certification.

UDOT’s acceptance of other WAQTC DOTs’ certifications also require that applicants sign the Rights and Responsibilities Agreement; two of the five WAQTC certifications (Aggregate and Embankment and Base) also require applicants to pass an exam that includes UDOT-specific field operating procedures.

Virginia DOT

VDOT’s website identifies reciprocity with NICET, ACI, and WACEL. VDOT was once a part of MARTCP, but no longer accepts MARTCP certifications (VDOT, n.d.-b).

The following certifications are accepted:

- NICET CMT Level II in Soils is allowed as a substitute to VDOT’s Soils and Aggregate Compaction certification.

- ACI-CFT Grade 1, WACEL Concrete Level 1, and NICET Level II CMT-Concrete are all identified as equivalents for concrete certification.

West Virginia DOT

The West Virginia DOT has a Policy for Materials Certification Reciprocity that describes a provisional path to certification for PCC Inspectors and Aggregate Technicians that involves receiving approval from the West Virginia DOT for consideration of existing outside certifications and taking a written exam (WVDOT, n.d.).

NETTCP

The DOTs that are identified as part of NETTCP responded to Question 14 of the survey that they accepted or required a regional program for reciprocity. NETTCP certifications are reciprocal to NETTCP member DOTs. As described in Chapter 4 and Chapter 6, NETTCP’s asphalt binder certification is reciprocal to the AI Binder certification because they were developed together.

WAQTC

The WAQTC member DOTs had varied responses to Question 14 as related to outside certifications. Some stated that they required a regional program for reciprocity, some indicated that they accepted outside certifications, and some (such as UDOT) indicated that they accepted outside certifications with additional requirements. WAQTC reciprocity is DOT-specific. WAQTC does not have stand-alone certifications; each DOT issues DOT-specific WAQTC certifications based on the WAQTC training materials. The WAQTC member DOTs use the same core training and can add DOT-specific exam sections to cover additional components.

Highlights—Reciprocity

Reciprocity is defined in the dictionary as a “mutual exchange of privileges.” Twenty-four of 52 DOTs (46 percent) address reciprocity in some manner. One common form of reciprocity was to recognize another DOT’s certification in order to allow a technician to take the certification exam without prerequisites. Four DOTs (8 percent) indicated that reciprocity was handled on a case-by-case basis. Reciprocity requirements were not found in some DOTs’ program documents or websites.

A recent guide developed for certification of construction inspectors identified the need for DOTs to consider reciprocity agreements with other DOTs. The guide noted that “Reciprocity agreements are signed documents stating that qualifications for certification of a construction inspector are the same or similar . . .” (Harper et al. 2023). The document also recognized that reciprocity of certifications could address local personnel shortages and provide DOTs with overall savings on training efforts.

The M-TRAC State Certifications Program Book contains information on 12 DOT certifications (those of the Arkansas, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin) as well as ACI certifications. Even without formal reciprocity agreements, having information on certifications gathered in a consistent manner, such as in the M-TRAC book, can be helpful to evaluate potential reciprocity. The Alabama DOT (ALDOT) was also found to have a clear format to identify their certification requirements.

ALDOT has 18 different certifications, and each has the certification requirements summarized in a “Summary of ALDOT Certification Requirements” table that provides information on the certification in a consistent format. The table includes information about prerequisites, training and testing, certification and recertification requirements, and decertification conditions. Each certification is linked to a procedure document describing the training and specific test methods in more detail.

Training—Programs and Online Resources

Table 25 illustrates responses to the survey question related to DOT training (Question 11). It shows the number of DOTs that identified a particular combination of entities as being related to training for the different materials. The table shows that there are 13 different combinations of training entities identified in the survey, with those for asphalt mixture and concrete having the most variations. The DOT is the predominate selection for each of the materials. Of the 52 DOTs, 15 (29 percent) selected only the DOT in relation to training for all four materials (those of Alaska, California, Delaware, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, North Dakota, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming). Seven (13 percent) of these DOTs also selected DOT only for all aspects of program management (the DOTs of Alaska, California, Georgia, Idaho, Louisiana, West Virginia, and Wyoming).

AASHTO R 25 Section 6 recommends a training program that may include “lecture, hands-on training, or self-study.” It references AASHTO Technical Training Solutions for instructor training, but it does not provide any details for online training. AASHTO’s Technical Training Solutions uses online interactive videos for training. Chapter 4 described different DOTs’ use of technology, including online training. Training materials, including complete manuals and online tutorials, were found in use by other DOTs in the DOT website review.

Online DOT Training Resources

Survey responses to Question 12 (see Chapter 3) show that of 52 respondents, 20 DOTs (38 percent) offer online training for soils and aggregate; 17 DOTs (33 percent) offer it for asphalt

Table 25. Combinations of entities involved in training (compiled from survey Question 11).

| Training* | Soils | Aggregate | Asphalt Mixture | Concrete | |

| DOT only | 24 | 20 | 20 | 16 | of 52 DOTs |

| 46% | 38% | 38% | 31% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT and outside contractor/consultant | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | of 52 DOTs |

| 6% | 4% | 6% | 2% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT and college/university | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | of 52 DOTs |

| 6% | 6% | 8% | 4% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT and OA | 2 | 4 | 3 | 6 | of 52 DOTs |

| 4% | 8% | 6% | 12% | % of DOTs | |

| C/C only | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | of 52 DOTs |

| 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | % of DOTs | |

| C/U only | 5 | 6 | 6 | 4 | of 52 DOTs |

| 10% | 12% | 12% | 8% | % of DOTs | |

| OA only | 7 | 9 | 10 | 13 | of 52 DOTs |

| 13% | 17% | 19% | 25% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT, C/C, and C/U | 1 | 1 | of 52 DOTs | ||

| 2% | 0% | 2% | 0% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT, C/C, and OA | 2 | of 52 DOTs | |||

| 0% | 0% | 0% | 4% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT and LTAP | 1 | of 52 DOTs | |||

| 2% | 0% | 0% | 0% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT, LTAP, OA | 1 | 1 | 1 | of 52 DOTs | |

| 0% | 2% | 2% | 2% | % of DOTs | |

| LTAP | 1 | of 52 DOTs | |||

| 0% | 0% | 2% | 0% | % of DOTs | |

| DOT, C/U, and OA | 2 | of 52 DOTs | |||

| 4% | % of DOTs | ||||

| No training | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | of 52 DOTs |

| 6% | 6% | 4% | 8% | % of DOTs | |

| No response | 1 | 1 | 1 | of 52 DOTs | |

| 0% | 2% | 2% | 2% | % of DOTs |

* Abbreviation key:

C/C = Contractor/consultant

C/U = College/university

LTAP = Local Technical Assistance Program

OA = Outside association

mixture; and 19 (37 percent) offer it for concrete. Nine DOTs (17 percent) required registration or a login to access the training; four DOTs (8 percent) link to outside training such as ACI or AASHTO Technical Training Solutions. Following is a discussion of the resources available through DOT websites, AASHTO, and YouTube.

AzDOT’s Resources section of the ATTI website (ATTI, n.d.) includes practice calculations and workbooks for each of the exams. The exams require an 80 percent passing minimum and are closed-book exams. Performance exams for each test method are also required. The Resources page provides links to over 40 videos on YouTube. The videos discuss and demonstrate over

40 individual test methods; 11 are AASHTO practices and methods and the rest are AzDOT methods.

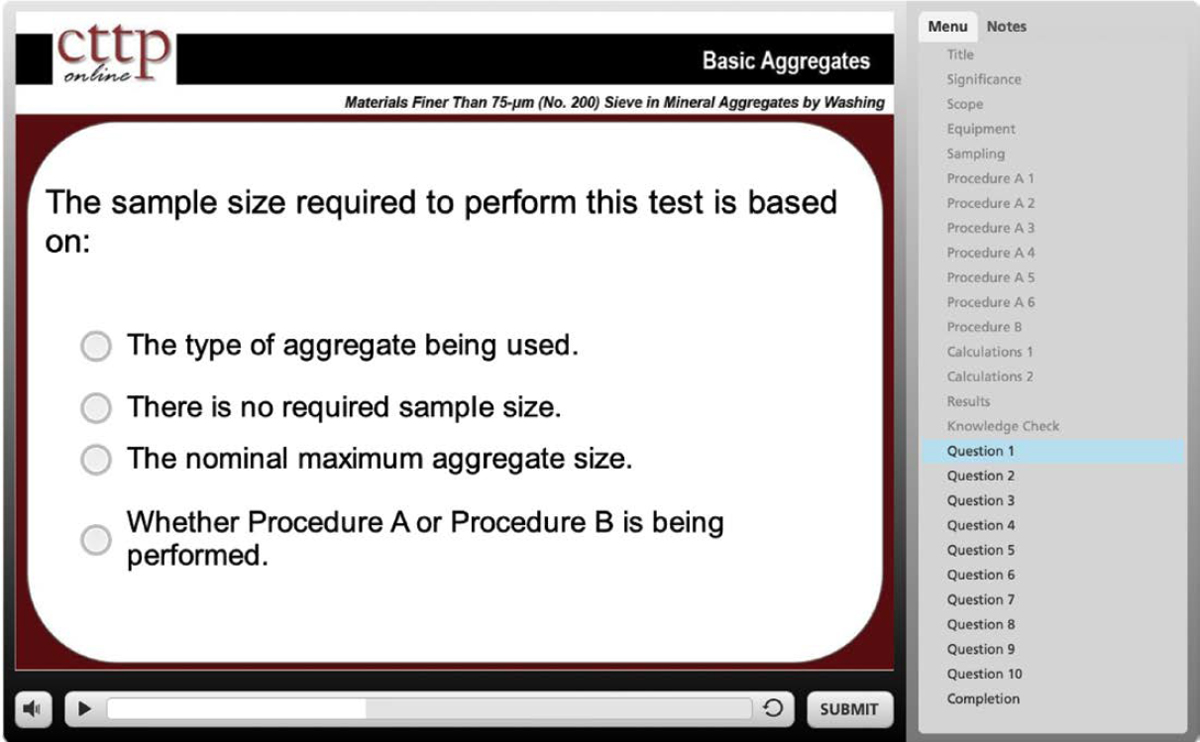

The Arkansas DOT has online video presentations based on AASHTO standards available through the University of Arkansas Center for Training Transportation Professionals. These training materials are available for review; registration in the course is required for certification. Topics include Aggregate, Hot Mix Asphalt, Concrete Field, Concrete Strength, Soils, and Basic Math. The website (University of Arkansas, n.d.-a) provides links to numerous YouTube videos to help applicants prepare for certification classes. The Arkansas DOT also has online classes that include practice exams (Figure 27) as well as homework problems that are similar to exam questions. The Arkansas DOT’s Center for Training Transportation Professionals program is run by the University of Arkansas.

CDOT produced training videos based on the WAQTC Embankment & Base/In-Place Density training materials, which are centered on the AASHTO standards. The videos are available on the CDOT Colleague Channel on YouTube (CDOT, n.d.). CDOT encourages review of the training videos for initial and recertifications.

The Iowa DOT training web page contains links to YouTube videos for sampling and testing of Aggregate, Hot Mix Asphalt, Concrete Field, and Soils based on Iowa test methods (IowaDOT, n.d.).

The Kentucky DOT Qualified Testers and Laboratories web page links to the University of Kentucky for Asphalt Training Testing webpage. The Superpave Plant Technologist (SPT) link includes videos for SPT Math Reviews. Other online training requires registration for the course.

Source: Center for Training Transportation Professionals

The Maryland DOT training webpage for MARTCP has links on YouTube to training videos based on Maryland test methods for Soils (MARTCP, n.d.).

MnDOT has a video library of resources for materials technicians (MnDOT, n.d.-b). Videos are based on AASHTO standards but may be modified as indicated.

The Mississippi DOT has concrete testing videos based on ACI-CFT Grade 1 on the Mississippi Concrete Association website (Mississippi Concrete Association, n.d.).

The Montana DOT offers online training, which is discussed in Chapter 4.

NDDOT offers video resources based on DOT test methods. The Technical Certification Program page includes links to an unlisted YouTube Channel (NDDOT, n.d.).

The North Carolina DOT webpage for Materials and Tests Unit Training Schools links to YouTube videos for ACI-CFT Grade 1 training (NCDOT, n.d.).

AASHTO Training Available Online

Some DOT websites included links to AASHTO Technical Training Solutions, which offers 114 web-based courses covering sampling and testing construction materials according to AASHTO standards. Courses are available for purchase through the AASHTO Bookstore. AASHTO Technical Training Solutions was discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

Training Available on YouTube

There are many videos posted on YouTube addressing construction materials sampling and testing. Many are based on DOT methods that may not agree with another specified method, some are not approved by the agency referenced, and some may not be current. The videos developed by CDOT were WAQTC-approved training videos, but other training videos were found online that reference WAQTC methods not developed or sanctioned by WAQTC.

Examination and Methods

AASHTO R 25 recommends that certifications involve written and performance examinations. AASHTO R 25 Section 7.4 notes that written examinations should have a designated time limit, and that the exams can be open- or closed-book. According to the website documentation, it was found that DOTs varied in using open- or closed-book exams, and some DOTs used open-book exams for some certifications and closed-book exams for others. Eleven DOTs (those of Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Minnesota, New York, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming) indicate through information on their websites that they use open-book exams; and nine DOTs indicate that they use closed-book exams (those of Arizona, Arkansas, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Montana, New Mexico, Utah, and Washington). Other DOTs (those of Colorado, Florida, Kentucky, Nevada, Ohio, and Tennessee) use open-book exams for some certifications and closed-book exams for others. It was unclear in some DOT website documentation whether open- or closed-book exams were used. The required percentage passing also varied. Either 70 percent or 80 percent passing was the most typical value required for written exams. ACI-CFT Grade 1 certification uses 70 percent overall and 60 percent for each test method as criteria for passing the written exam, and pass/fail for the performance exam. WAQTC similarly identifies written exam criteria of 70 percent passing with a minimum score of 60 percent for each method. NETTCP uses the same criteria for most of their certification written exams (70 percent overall and 60 percent per section), but a few of the NETTCP certifications have an 80 percent passing requirement.

Certification—Recertification and Decertification

Recertification

AASHTO R 25 Section 8.7 recommends that a recertification policy be developed and suggests that it may include written and performance exams along with refresher courses. It also includes a note stating that some DOTs have used IA to replace performance examinations in recertifications.

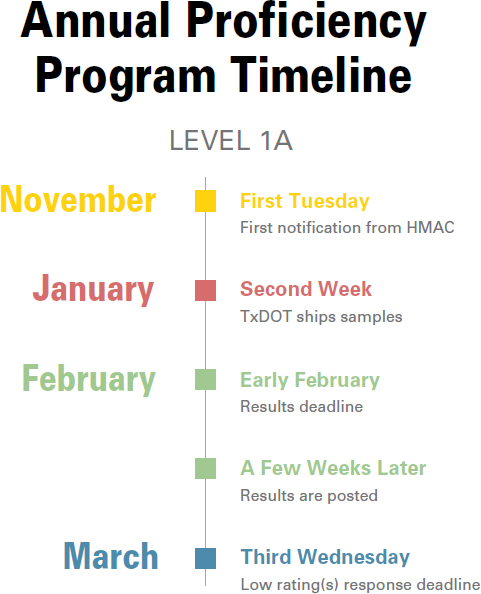

For example, the Texas DOT (TxDOT) was identified as using IA as part of its certification program. TxDOT requires certified technicians that are “Specialists” (Level 1A, AGG101, SB101, SB201, and SB202) to participate in annual proficiency or split sample tests for IA purposes, along with normal certification requirements. The results are required to be within two standard deviations. As an example, Level 1A Certified Plant Production Specialists were notified in November 2023 that they are required to perform and submit test results for some of the asphalt test methods used by TxDOT, including asphalt content by the ignition method, theoretical maximum specific gravity, bulk specific gravity, and sieve analysis of the extracted aggregate. The samples are shipped to the technicians, and deadlines are communicated online through Hot Mix Asphalt Center (HMAC) flyers. Technicians are given worksheets in order to submit their results in a consistent format by the deadline. A recent flyer is shown in Figure 28.

Decertification

AASHTO R 25 Section 8.8 recommends a written policy for removing technician certification; the use of progressive discipline is noted as a method of decertification. FHWA recommends that DOTs have a documented policy for removing technician certifications as part of their guidelines as well as in their QA evaluation tool (described in Chapter 2). Forty-seven of the 52 DOTs in the survey (90 percent) indicated that they have a decertification process.

NETTCP has a Code of Ethics that the technicians must sign as part of certification. The Executive Director and Executive Committee jointly address infractions.

WAQTC has an Administration Manual that documents negligence and abuse as two potential reasons for revocation or suspension. It is recommended that the individual DOTs’ AQC review any actions or appeals.

Individual state employment law is expected to affect the way DOTs handle decertification policies. The Idaho DOT is a WAQTC member and it follows the general WAQTC procedures, but the appeal process in their manual specifically notes Idaho Code 67-5201 for their appeals process. Technician appeals involve the DOT’s chief engineer for a final order; further appeals go to district court.

DOTs’ decertification processes often involve DOT personnel as part of the investigation but may also include outside entitles in an appeal board. Kansas DOT’s Policy and Procedure Manual for its CIT program describes 11 different infractions (beyond cheating on a test) that are subject to an investigation by the DOT. Based on the results of the investigation, a three-member review committee composed of DOT employees may get involved. If an action is found to be warranted, the technician can appeal to an appeals committee that includes one member from a local public authority and two DOT members.

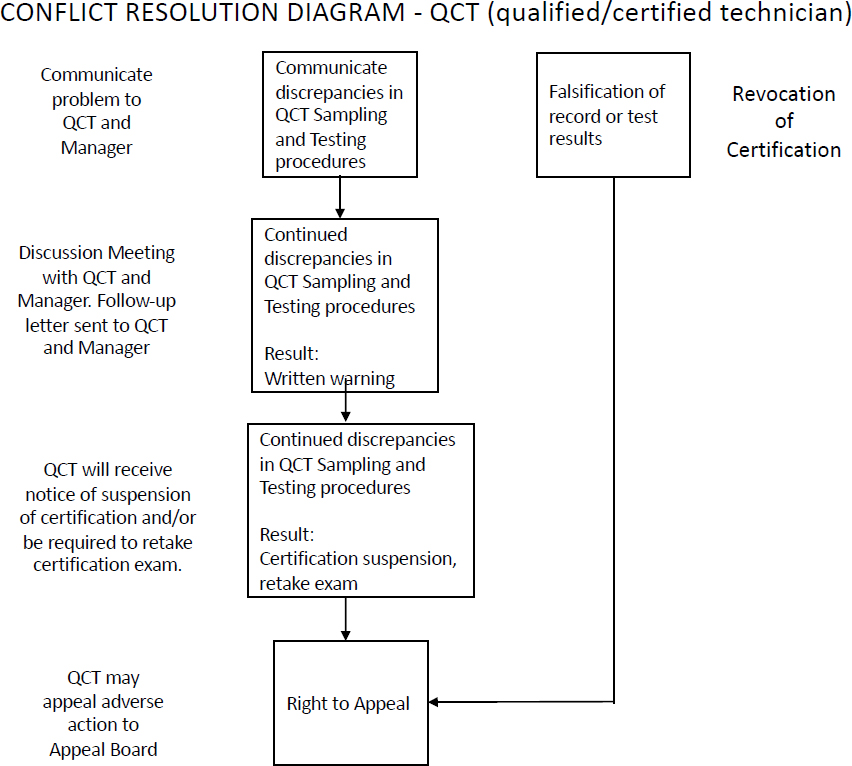

The Georgia DOT (GDOT)’s Quality Control Technician Training and Qualification Program and Roadway Testing Technician Training and Qualification Program (RTTTQP) documents specifically note that they were developed from AASHTO R 25 and even follow the headings used in the standard. The Conflict Resolution Diagrams (generic example shown in Figure 29) included in both documents are similar and were based on GDOT’s own personnel policies related to verbal and written warnings and progressive discipline. The Appeals Board for GDOT in the asphalt area is composed of five members (two from the DOT and one representative each from a consultant, contractor, and FHWA) with the GDOT Director of Construction as the chair. Appeals for the RTTTQP (which is focused on nuclear density-type testing) are heard by the GDOT Director of Construction.

DOT Certification Program Findings Summary

Certification or qualification programs are used in some form by all DOTs.

The complexity, similarities, and differences of each of the DOT programs vary. NCHRP has performed two previous syntheses related to QA. An NCHRP synthesis on acceptance practices published in 1998 (after the 1995 change in 23 CFR 637B but before the June 29, 2000, deadline that required qualified sampling and testing personnel) noted that “the most difficult aspect of the synthesis was trying to identify consistent patterns among the DOT practices” (Smith 1998). A later synthesis of State Construction Quality Assurance Programs (Hughes 2005) noted that almost half of the agencies anticipated significant changes in their QA program “in the near future.” At the time of that synthesis, it was found that most agencies used in-house training and certification programs. Based on the results of the survey for this synthesis and the 10 individual DOT case examples discussed in Chapter 4, it is evident that practices are still varied. There is also evidence that there have been changes in the use of external certifications. In the 2005 synthesis study, only 16 of 40 DOT responses (40 percent) used ACI for concrete certification; this synthesis (survey described in Chapter 3) found that 49 of 52 DOT responses (94 percent) either accept or require ACI certifications.

AASHTO R 25 provides some directions and recommendations for the development and operation of technician certification programs for DOTs. The standard and other guidelines for DOT certification programs is very flexible, providing for variability in the different programs.

This chapter shared that although DOTs are the predominate lead for the daily management and training used in certification programs, there are over a dozen different combinations of entities involved in both the certification program management and associated training. This structure also may be different for the different materials. Only seven of 52 DOTs surveyed (13 percent) did not identify other entities (outside contractors/consultants, colleges/universities, or outside associations) in their certification management or training program.

Prerequisites for certification are also different. Information from 20 DOTs’ websites indicate that they recommended or required experience prior to certification; other DOT programs specifically noted that they were focused on basic sampling and testing competency.

Reciprocity with other DOTs was identified in the survey and in this chapter. Reciprocity was predominately defined as allowing the technician to take the certification exam without taking the associated training. This was evident in the responses of the 52 DOTs surveyed, as 29 DOTs (56 percent) include DOT specifications in their exams. Although some DOTs specifically identified reciprocity with other DOTs, case-by-case approval was also used. ACI-CFT Grade 1 was accepted the most by DOTs, but because ACI does not have a decertification policy, DOTs also required the technician to submit their ACI certification in order to receive a DOT certification.

As AASHTO R 25 notes, reciprocity decisions can be aided by a clear description of the certifications (such as specifics on training, test methods, and use of performance and written exams) and a uniform format. The Colorado DOT and Alabama DOT tables discussed in this chapter

and the M-TRAC State Certifications Program Book are examples of different formats that can be used.

Examination methods in use are as varied as the programs themselves. There was no predominate use of open-book or closed-book exams. Although 70 to 80 percent is the most common criteria found for passing the written exams, the passing percentage varied by DOT and even by material or certification level in a DOT. The most common external certification (ACI-CFT Grade 1) uses 70 percent overall and 60 percent for each test method as the criteria for passing the closed-book written exam, and pass/fail for the performance exam.

Decertification policies were found that require a technician to sign a document recognizing the policy. The DOT or a DOT along with an industry group were involved in reviewing decertification issues. AASHTO R 25 recommends the use of progressive discipline, which was found to be in use for negligence-type infractions; more stringent measures were found for infractions that could be considered intentional.