Cooperating with Nature: Confronting Natural Hazards with Land-Use Planning for Sustainable Communities (1998)

Chapter: Part One: The Choices of the Past 2 Planning and Land Use Adjustments in Historical Perspective

CHAPTER TWO

Planning and Land Use Adjustments in Historical Perspective

RUTHERFORD H. PLATT

FROM THE DAWN OF CIVILIZATION, humans have struggled to predict, prepare for, survive, and recover from natural disasters. The tale of Noah's flood in the Old Testament Book of Genesis, whether or not apocryphal, represents perhaps the earliest "documented" instance of flood hazard mitigation. One can assume that antiquity witnessed countless unrecorded episodes of coping with such eternal perils as fire, flood, earthquake, volcano, drought, famine, plague, and pestilence. The civilizations of the ancient Nile and Tigris-Euphrates Valleys clearly recognized how to derive agricultural benefits from floodplains while placing their settlements on higher ground if available. The colonial enclaves established by Greece and Rome chose sites, where possible, that were both militarily defensible and relatively safe from flood.

But the historical record on natural hazard mitigation, at least in Western Civilization, is sketchy until the Renaissance. Advances in literacy, technology, scientific knowledge, and the diminishing influence of unquestioning belief in an omnipotent and punishing God all contributed to the awakening recognition that human settlements may be designed or redesigned to

be safer from natural and other perils. In fact, the idea that ordinary people are worth protecting from disaster was a precondition to examining why and where disasters occur and what may be done to reduce their effects.

LEARNING FROM DISASTER

The beginning of wisdom concerning disasters is the recognition that choices must be made, both in the original layout of new settlements in hazardous areas, and in recovery after a disaster strikes. Indeed, the aftermath of disaster offers a critical opportunity to review the choices available and possibly to select modification of the status quo ante to achieve greater protection from future disasters. Communities need not suffer destruction over and over again from the same natural hazard. As the experiences to be related from the Great Fire of London in 1666, the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, and the Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989 illustrate, the recognition of choices in the wake of disaster is fundamental to greater security.

The Great Fire of London: Seizing the "Window of Opportunity"

Perhaps the first disaster to stimulate deliberate and well-documented changes in public policy was the Great Fire of London of 1666. This event, which burned most of the medieval part of the city within the old Roman Walls in three days, was faithfully chronicled by educated observers including Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn.

The fire epitomized Garrett Hardin's (1968) gloomy axiom "Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all." Neglect of the urban environment after a period of rapid population growth during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—combined with dry, windy conditions—led to disaster. The city's few public spaces had been encroached on by private structures clogging the narrow lanes and passageways and blocking access to the Thames River. In the absence of effective regulation of building size, location, and construction materials, the fire was inevitable. Without access to water, it could not be halted.

The point was not missed by certain leading minds of the time. While the ruins were still smoking, plans, or at least concepts, for the rebuilding of London were being prepared by Sir Christopher Wren, the city's leading architect, and several others (Bell [1920] 1971, Chapter 13).

Wren proposed to transform the city into a monumental, baroque-style imperial capital, much as Haussmann would restructure Paris in the mid-nineteenth century. But such a radical proposal for restructuring the city was incompatible with the culture and economy of England at that time. The government could not afford to pay property owners whose private lots would have been taken to implement the plan (a very modern dilemma).

A week after the fire had subsided, the recently restored sovereign, Charles II, addressed by proclamation the need for restraint and foresight in rebuilding, pending a full investigation of the causes of the disaster. Rasmussen ([1934] 1967, p. 117) praised this proclamation as "astonishingly modern . . . a true piece of town-planning, a program for the development of the town." The proclamation addressed five practical aspects of the rebuilding process: (1) using stone or brick on exterior facades in place of wood; (2) setting minimum width of streets; (3) reserving open space along the Thames River to preserve access to water for firefighting; (4) removing public nuisances such as breweries or tanneries from central London; and (5) paying reasonable compensation to property owners whose right to rebuild was curtailed by public restrictions.

Charles II then appointed a special investigative commission (like a modern mayor appointing a "blue ribbon committee") to draw up recommendations for future building practices in London. Christopher Wren served on the commission and was to be a principal figure in the reconstruction of the city. Based on the royal proclamation and the commission's report, the "Act for Rebuilding London" was adopted February 8, 1667. The act has been described as London's first "complete code of building regulations" (Bell [1920] 1971, p. 251). While not fulfilling Wren's baroque vision (which he did instill in his new St. Paul's Cathedral), the rebuilt London proved durable: even the Nazi blitz failed to destroy London as completely as the Great Fire.

The Lisbon Earthquake of 1755: Assessing Options for Recovery

Less than a century after London's Fire, Portugal's capital of Lisbon was devastated by a major earthquake, which killed up to 30,000 people and destroyed much of its medieval core. As in England, experts were assembled under sovereign decree to assess whether and how the city should be rebuilt. The Marques de Pombal, a key royal advisor, was

appointed to direct the recovery process. Recognizing the recurrent nature of the earthquake hazard, Pombal in modern fashion reviewed a range of options: (1) no change in streets or building lines; (2) widening of streets with little change in densities; (3) total demolition and replacement in the same location; (4) relocating the capital elsewhere (Mullin, 1992).

While London effectively followed the second approach, Lisbon chose the third. The Baixa district (the "lower town"), situated in the area of greatest seismic risk, was to be entirely leveled, replanned, and reconstructed. Pombal obtained a series of alternative plans for the rebuilding of the Baixa. The one selected accomplished several objectives: (1) it replaced the old medieval wooden city with stone and stucco in the manner of London, (2) it reoriented streets to gain maximum exposure to sunlight, (3) it linked commercial and royal districts of the city, (4) it eased circulation in the heart of the city, and (5) it created open space for ceremonies and access to the river. According to Mullin (1992, p. 168): "At once, ceremony, iconography, commerce, bureaucratic functions and everyday interaction were served."

As with the rebuilding of Paris by Baron Haussmann a century later, the reconstruction of Lisbon reflected the declining dominance of royalty and the church, and the emerging role of the commercial middle class. It provided order, relative safety from future earthquakes and fires, and an ornate capital setting for the Portuguese nation-state of the nineteenth century.

The San Francisco Earthquake of 1906: Confronting the Limits of Technology

It would be a century and a half before another catastrophic earthquake struck a large city: San Francisco in 1906. By the turn of the twentieth century, San Francisco had acquired a population of one-third of a million, and was well established as one of the leading American cities. Other cities, most recently Chicago, had experienced catastrophic fires. But no city in North America had been consumed by fire triggered by an earthquake. Like the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, the San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906 shattered conventional assumptions regarding the ability of modern technology to overcome natural perils. And just as the loss of the Titanic led to tightening of safety requirements for ocean vessels, the San Francisco earthquake in time would stimulate actions there and elsewhere to mitigate the severity of future disasters.

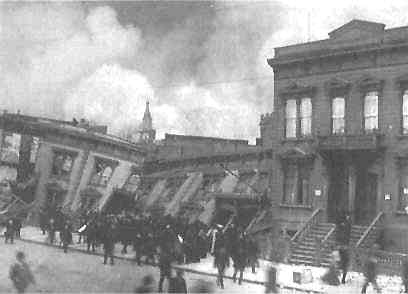

The San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. This row of buildings tilted when the ground beneath them slumped because of the intensity of ground shaking. This photo was taken before fire destroyed the entire block (note smoke in the sky) (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Geophysical Data Center).

The San Francisco earthquake and fire of April 18, 1906, is still considered America's worst urban natural disaster and one of the world's worst urban conflagrations (a list which now includes the Oakland 1991 firestorm). It burned an area of 490 blocks covering about 3,000 acres—six times the area burned by the Great Fire of London in 1666 and half again as much territory as the 1871 Chicago fire. The San Francisco fire and earthquake killed approximately 500 people and destroyed the entire business district and the homes of three-fifths of the city's inhabitants (Bronson, 1986).

The 1906 catastrophe exhibited many characteristics of contemporary urban natural disasters: (1) multiple interrelated hazards (earthquake and fire); (2) failure of lifelines (water, communications, transportation) which caused secondary impacts; (3) widespread structural damage due to inadequate building standards and prevalent use of wood for smaller structures; (4) resulting homelessness and joblessness of much of the working-class population; but (5) a nurturing external society that as-

sisted in the immediate aftermath to the disaster and to some extent in the longer-term recovery. Missing from the San Francisco catastrophe, as compared with modern disasters, was any significant assistance from the national government. Most help was rendered by states, cities, churches, and other voluntary donors.

The foremost public action in response to the catastrophe was the development of an external water supply derived from damming of the Hetch Hetchy Valley in the Sierra Nevada, some 150 miles east of the city. The proposal by the City of San Francisco to construct a dam within Yosemite National Park precipitated a ten-year controversy between advocates of wilderness preservation, headed by John Muir, and proponents of ''wise use of natural resources" represented by Gifford Pinchot, Director of the U.S. Forest Service and advisor to President Theodore Roosevelt. The dam and reservoir were finally approved in 1913 and have since provided San Francisco with a high-quality source of drinking water. But the reliability of the system in the event of another major Bay Area earthquake remains in doubt. The Hetch Hetchy water pipes extend across the Hayward Fault in the East Bay and thus could rupture in an earthquake there, potentially leaving San Francisco once again deprived of its water supply (a problem shared by its East Bay neighbors).

San Francisco recovered rapidly from the 1906 catastrophe chiefly because the downtown business district was well insured. Total insurance payments amounted to $5.44 billion (1992 dollars), by far the worst urban fire insurance loss in American history. However, like London after its fire in 1666, San Francisco declined to alter its basic pattern of streets and land use patterns as it rebuilt. In particular, it ignored Daniel H. Burnham's "City Beautiful" plan for the redesign of the city that had been presented to civic leaders just before the fire: "Few cities ever found themselves demolished, with a ready-made plan for a new and grander city already drawn up, awaiting implementation, and with money pouring in to help realize the plan. San Francisco chose to ignore its Burnham Plan, and decided instead to build at a rate and manner which made the city not only less beautiful than was possible, but more dangerous. The rubble of the 1906 disaster was pushed into the Bay; buildings were built on it. Those buildings will be among the most vulnerable when the next earthquake comes" (Thomas and Witts, 1971, p. 274). This statement was prophetic: the city's Marina district, built on 1906 rubble, sustained heavy damage in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

The Loma Prieta Earthquake: Lifeline Failures

Modern urban disasters, particularly earthquakes, involve disruption of public and private lifelines such as bridges and highways, communications, electrical facilities, water, food supplies, and medical care. The failure of lifelines, by definition, amplifies the geographic, economic, and social consequences of a natural disaster. The Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989 was, like the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, notable for significant lifeline failures. Such failures on an even larger scale followed the Northridge earthquake of 1994 and the Kobe earthquake in Japan in 1995.

On October 17, 1989, the San Andreas Fault reawakened in the Bay Area with a 7.1 magnitude earthquake, the first of that magnitude since 1906. The fault ruptured over a distance of 25 miles at a depth of 12 miles below the surface; no surface faulting appeared (Bolin, 1993b; FEMA, 1991). Seismic shaking lasted 15 seconds, followed by numerous aftershocks. The event was felt over an area of about 400,000 square miles extending southward as far as Los Angeles and northward to the Oregon border. It caused 62 known deaths and 3,757 injuries, and left 12,000 people homeless. The quake resulted in over $6 billion in property damage and disrupted public transportation, utilities, and communications. Occurring just before a World Series game, ironically between the San Francisco Giants and the Oakland Athletics, the earthquake presented an unparalleled opportunity to raise public awareness of seismic hazard.

Although the epicenter was in a rural upland well south of the major population centers of the Bay Area, it nevertheless caused dramatic and costly damage to infrastructure and older private buildings on both sides of the Bay. In general, French (1990) has identified four classes of infrastructure damage caused by the Loma Prieta quake:

-

Direct physical and economic damage to infrastructure systems themselves

-

Diminished ability to carry out emergency response activities

-

Inconvenience due to temporary service interruption

-

Longer-term economic losses due to the length of time required to rebuild.

The most horrifying result of the earthquake was the collapse of a 1.5 mile double-deck section of a major commuter freeway constructed

on bay mud in Oakland. The collapse trapped hundreds of cars and accounted for 41 of the 62 deaths attributable to the earthquake. For several days, the nation witnessed on television the heroic rescue of survivors from their vehicles trapped under the collapsed rubble of the upper deck. The last living victim was removed from his car after 90 hours. (Even more extensive freeway damage would occur in the January 17, 1994, Northridge earthquake in southern California.)

Another lifeline failure was the collapse of a 50-foot section of the upper deck of the San Francisco—Oakland Bay Bridge, the only direct vehicular link between San Francisco and the East Bay. Its closure for repairs forced the cross-Bay commuters to take circuitous routes far to the north or south, or to rely on the BART rapid transit system, which was not damaged. Cross-bay ferry service was also revived. In San Francisco, Interstate Highway 280 and the incomplete Embarcadero Freeway were also damaged. Elsewhere, many local roads and highways were blocked by landslides triggered by ground shaking.

Structural damage was concentrated in cities close to the epicenter, particularly Santa Cruz. But many older unreinforced masonry buildings were damaged in Oakland (including its City Hall) and in San Francisco. Damage in both cities was primarily caused by ground shaking on unconsolidated filled lands along the bay, as predicted by Thomas and Witts (1971). As in 1906, local water mains ruptured, leading to loss of water pressure for firefighting. A fireboat helped to pump bay water and local citizens organized bucket brigades to save the Marina District.

Elsewhere, damage was more related to soil propensity for ground shaking than to distance from the epicenter. Many critical facilities including several hospitals were damaged in locations where hazardous soil conditions could have been recognized. Stanford University in Palo Alto, which was severely hit by the 1906 earthquake, suffered $160 million in damage from Loma Prieta. Public schools were generally not badly damaged due to earthquake construction codes adopted after the 1933 Long Beach earthquake in southern California. The East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD), which supplies water to 1.5 million people in the East Bay region, experienced some 200 local water main breaks, but its main supplies were not affected (FEMA, 1990).

Loma Prieta was a wake-up call to the Bay Area, which would be reinforced by the 1994 Northridge earthquake in Southern California and the Kobe earthquake in 1995. While building codes have been gradually upgraded in California and elsewhere to protect against earthquake damage to individual structures, the prospect of massive lifeline failures

in metropolitan regions is daunting. Preparedness for the proverbial "Big One" is the highest-priority issue in natural hazard planning for FEMA and the State of California.

FLOOD DISASTERS: A RANGE OF ADJUSTMENTS

The Mississippi-Missouri River system is second in the world only to the Amazon River in main-stem length (3,799 miles) and ranks behind only the Amazon and the Congo Rivers in watershed area. But in contrast to most other great rivers, the Mississippi-Missouri system drains a fertile and largely inhabitable heartland.

The Mississippi-Missouri watershed, comprising about 41 percent of the land area of the conterminous United States, is a region of great climate variability. Average annual precipitation ranges from less than 20 inches in the upper Missouri basin in the west to more than 50 inches in the Ohio River basin in the east. High levels of river flow result from seasonal snowmelt in the northern portions of the basin and from storm systems that move across the region from west to east at any time of year. Tropical hurricanes emerging from the Gulf of Mexico in late summer and fall occasionally threaten the lower valley with heavy rainfall, wind, and coastal storm surges. All of these climatic phenomena contribute to recurrent and occasionally massive floods along the Mississippi and its tributaries.

More than any other river system, Mississippi floods have consistently attracted national attention and, when flooding causes widespread losses, national response. The policies of the United States towards flooding have to a great extent been forged in the incessant quest for a reasonable accommodation between human settlement and natural hazard in the Mississippi River valley.

Early plantations established along the river in the eighteenth century under French rule sought to protect themselves from floods and channel shifts by building levees on their respective lands. These individual private levees to control the river were largely ineffective against major floods because they were discontinuous and of uneven height and durability.

With the accession of the region by the United States through the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, local interests increasingly sought governmental assistance and protection. The Army Board of Engineers in 1825 was authorized to undertake waterway improvements, but for several

decades these were intended primarily to aid navigation. In 1861, two army engineers, Abbot and Humphreys, proposed a system of levees along the Mississippi River to enhance navigation and also provide flood control. This approach, known as the "levees only" policy, was adopted. A series of further floods prompted Congress to establish the Mississippi River Commission, a joint military-civilian board that continues to oversee federal efforts to contain the lower Mississippi today. The commission attracted humorous skepticism from Mark Twain in his 1882 book Life on the Mississippi. Notwithstanding Mark Twain's doubts, the lower Mississippi was lined with federally designed and funded levees by the early twentieth century. Levees were also beginning to appear along segments of the upper Mississippi and its navigable tributaries.

Faithful to the "levees only" policy, flood control dams for upstream storage were not built on the Mississippi before the 1930s. Upstream storage was first used on a large scale in the Miami River basin in Ohio following disastrous floods there in 1913. The Miami River Conservancy District, organized under a state law passed the following year, constructed a series of five dams to impound flood runoff in reservoirs that remained empty when not needed for that purpose.

The great lower Mississippi River flood of 1927 prompted Congress to scrap the "levees only" policy and expand the range of engineering approaches to controlling the river. The 1927 flood reclaimed most of the alluvial valley from the Ohio River to the Gulf. Hundreds of levees were breached or overtopped. Some 20,000 square miles of land were inundated, 700,000 people were displaced, over 200 were killed, and 135,000 structures were damaged or destroyed.

Seldom has a policy change been so quickly and clearly adopted in the wake of a natural disaster. The lower Mississippi Flood Control Act of 1928 authorized a series of dams and flood storage projects, channel improvements, floodways, and other measures for the valley. According to two eminent hydrologists, Hoyt and Langbein, "Few natural events have had a more lasting impact on our engineering concepts, economic thought, and political policy in the field of floods. Prior to 1927, control of floods in the United States was considered largely a local responsibility. Soon after 1927 the control of floods became a national problem and a federal responsibility" (1955, p. 261).

After disastrous floods in the Ohio Valley and New England in 1935 and 1936, the Flood Control Act of 1936 shifted the focus of Army Corps of Engineers flood activities beyond the Mississippi Valley to the entire nation. The act authorized 218 new projects nationally, includ-

ing several multiple-purpose projects. Federal funding was contingent upon nonfederal cost-sharing and upon a benefit-cost analysis that determined that a project would be cost-effective. But in the Flood Control Act of 1938, Congress assumed full federal funding of upstream flood control dams and reservoirs, while levees remained subject to local contribution.

During the 1930s and the New Deal, some of the world's largest and most admired multipurpose river development projects were completed. Foremost among these was the system of main-stem and tributary dams constructed by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). The TVA was chartered by Congress in 1933 as a public corporation to focus federal resources upon an impoverished and environmentally stressed region, the drainage basin of the Tennessee River. The TVA is best known for its series of main-stem dams which harnessed the river for power, navigation, recreation, and flood control. But the TVA also developed pioneering programs in floodplain management, soil erosion management, reforestation, economic development, and improvement of housing, medical care, schools, and recreation. It proved to be an internationally important experiment in governmental resource management. Although no other similar agencies were established in the United States, the TVA demonstrated that it is possible to promote regional development through comprehensive river basin management (White, 1969). The concept of river basin planning was further promoted through the many reports of the National Resources Planning Board during the 1930s.

Federal flood control and multipurpose river development projects were undertaken on the Columbia, the Colorado, the Sacramento, and in the east in more limited form on the Connecticut, the Delaware, the Potomac, and elsewhere. Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia and Hoover Dam on the Colorado remain two of the most impressive concrete dams in the world.

Between 1936 and 1952, Congress spent more the $11.1 billion for flood control, of which $10 billion was allocated to the Corps of Engineers (not adjusted for inflation). The cost of Corps flood control projects in the lower Mississippi River valley alone between 1928 and 1983 was estimated at $10 billion. After the 1993 floods on the upper Mississippi and Missouri rivers, the Army Corps of Engineers reported that all federally constructed facilities performed as designed and prevented $19.1 billion in flood losses (Interagency Floodplain Management Review Committee, 1994, p. 21).

The concept of floodplain management through land use planning

and restrictions was relatively late to appear. In the early 1950s, the Tennessee Valley Authority initiated a floodplain mapping and information program under the direction of James E. Goddard. This would in turn stimulate the Army Corps of Engineers to initiate a wider flood information program around 1961, which continued until the primary function of mapping floodplains was assumed by the National Flood Insurance Program. However, communities were slow to translate improved information into land use regulations. In 1955 Hoyt and Langbein wrote, "Flood zoning, like almost all that is virtuous, has great verbal support, but almost nothing has been done about it" (p. 95).

Nonstructural Approaches to Flood Control

The National Flood Insurance Program

The geographic focus of flood policy attention shifted to the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts in the wake of a series of vicious hurricanes during the 1950s and 1960s. In 1965, Congress called for a study of flood insurance and other measures as alternatives to structural flood control and disaster assistance. Two ensuing reports, respectively authored by resource economist Marion Clawson and geographer Gilbert F. White, recommended that a national flood insurance program might be feasible if it contained requirements for land use controls and building standards to reduce future losses. Congress responded by passing the National Flood Insurance Act.

This act established the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which has become the primary vehicle of federal flood policy. This program serves three interrelated congressional objectives. First, the NFIP seeks to reallocate a portion of the burden of flood losses to all occupants of flood hazard areas through the mechanism of insurance premiums. Second, it seeks to reduce steadily increasing flood losses by limiting additional development and investment at risk in floodplains. Third, the NFIP calls for mapping of flood hazard areas across the United States; the program has spent over $900 million for this purpose since the law was enacted. In order for insurance to be available to property owners, the community in which their land is located must regulate new and rebuilt structures in the flood hazard area according to standards set by the NFIP, particularly the elevation of the lowest floor of a structure above the estimated local "base flood" level. Currently over 18,000

municipalities and counties have adopted such regulations and are eligible for flood insurance coverage.

The 1973 Flood Disaster Protection Act, adopted after Tropical Storm Agnes devastated the Middle Atlantic states, made flood insurance purchase compulsory for anyone borrowing money from a federally related lender to purchase or develop property in identified flood hazard areas. This requirement helped boost participation in the National Flood Insurance Program to a level of about 3.3 million policies by 1996, with total coverage of over $300 billion.

Besides the National Flood Insurance Program, nonstructural flood loss reduction has included several other measures, for example, improved weather forecasting and warning systems, preparedness and evacuation planning (particularly in areas subject to hurricanes), flood-proofing of existing structures, and relocation of certain structures in locations subject to chronic flooding.

Also as a condition of eligibility for flood insurance, the National Flood Insurance Act required land use planning for and management of identified flood hazard areas. This planning and management was to be a joint responsibility of the federal government, states, and local communities. The Federal Insurance Administration (until 1979 a unit of the Department of Housing and Urban Development and thereafter of the Federal Emergency Management Agency) was required to "develop comprehensive criteria designed to encourage, where necessary, the adoption of adequate state and local measures which . . . will: (1) constrict the development of land which is exposed to flood damage where appropriate, [and] (2) guide the development of proposed construction away from locations which are threatened by flood hazards" (P.L. 90-448, sec. 1361; U.S. Code, vol. 42, sec. 4102).

Floodplain Zoning

The Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973 made land use management and participation in the NFIP prerequisites for federal financial assistance including disaster assistance. And in contrast to the use of "encourage" in Section 1361 of the 1968 law, the 1973 law stated the intent of Congress to "require states or local communities as a condition of future federal financial assistance, to participate in the flood insurance program and to adopt adequate floodplain ordinances with effective enforcement provisions consistent with federal standards to reduce or

avoid future flood losses" (P.L. 93-234, sec. 2(b)(3); U.S. Code, vol. 42, sec. 4002(b)(3), emphasis added).

But uncertainty lingered as to whether floodplain zoning that precluded use of privately owned flood hazard areas was constitutional or not. Since its origins in the early twentieth century, the planning and zoning movement in the United States had taken little notice of natural hazards. Zoning—the division of a community's land area into districts of specified land uses and densities—had largely been employed to protect single-family neighborhoods from incompatible neighbors, and later to insulate suburban communities from unwanted forms of housing, commerce, and public facilities. Until the late 1960s, natural hazards had generally been assumed to be controllable through technology and were therefore not considered an impediment to development.

In the first comprehensive legal review of floodplain zoning, law professor Allison Dunham (1959) found few judicial cases on the subject. However, he urged that such measures should be held valid to protect (1) unwary individuals from investing or dwelling in hazardous locations, (2) riparian landowners from higher flood levels due to ill-considered encroachment on floodplains by their neighbors, and (3) the community from the costs of rescue and disaster assistance.

In 1972, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in Turnpike Realty Co. v. Town of Dedham (284 N.E.2d, at 891) at last provided a strong decision upholding a local floodplain zoning ordinance. The case involved a 61-acre parcel located in a wetland adjoining the Charles River in eastern Massachusetts which the plaintiff sought to fill and develop. The town refused permission to do so under its 1963 "floodplain district" law. The purposes of the law included: (1) protection of the groundwater table; (2) protection of public health and safety against floods; (3) avoidance of community costs due to unwise construction in wetlands and floodplains; and (4) conservation of "natural conditions, wild life, and open spaces for the education, recreation and general welfare of the public" (284 N.E.2d, at 894). The last objective raised the specter of "public benefit" which normally is a forbidden purpose of zoning. The Massachusetts court, however, accepted the first three purposes as valid and ruled that since "the by-law is fully supported by other valid considerations of public welfare," the conservation of natural conditions would be acceptable as well.

Although the plaintiff claimed that the site was only flooded due to improper operation of a floodgate, the court found the site to lie within the natural floodplain of the Charles River. It cited testimony as to

recent severe flooding of the site. Relying on the Dunham (1959) rationale stated above, the court upheld the measure, declaring, "The general necessity of floodplain zoning to reduce the damage to life and property caused by flooding is unquestionable" (284 N.E.2d, at 899).

During the 1970s and the 1980s, state and local floodplain regulations were widely adopted in response to the National Flood Insurance Program and increasing public recognition of coastal and riverine flood hazards. Upon challenges to such laws, courts generally followed the Turnpike Realty rationale and upheld the constitutionality of floodplain regulations (Kusler, 1982). State floodplain managers funded by FEMA assisted elected officials and judges in understanding flood hazards. Their professional organization, the Association of State Floodplain Managers, has contributed through its conferences and publications to the acceptance of floodplain management, including land use regulations.

LAND USE REGULATION REGARDING OTHER HAZARDS

In contrast to floods and coastal hazards, there is no congressional mandate for land use planning and regulation in the case of seismic hazards, landslides, or urban-wildland fire risk areas. Whatever the shortcomings of its implementation, the NFIP has at least promoted the idea of regulating development in identified flood hazard areas. The Earthquake Hazards Reduction Act of 1977 (P.L. 95-124; U.S. Code, vol. 42, sec. 7701) established a program of research and technical assistance to states and local governments but stopped short of establishing a mandate for planning and regulation of land use and building practices. In 1993, a review by the former Federal Insurance Administrator George Bernstein found mitigation of earthquake hazards to be inadequate due to the voluntary nature of the national program. In particular, he found that "neither improved design and construction methods and practices nor land use controls and redevelopment have been implemented broadly enough to hold out promise for comprehensive hazard reduction throughout the United States" (Bernstein, 1993, p. 28). As discussed below, land use planning has likewise not been utilized widely in the aftermath of such wildfire disasters as the Oakland fire of 1991.

THE PROPERTY RIGHTS MOVEMENT: PUTTING THE BRAKES ON LAND USE MANAGEMENT?

In the mid-1990s, the climate of political and judicial approval of floodplain regulations may be weakening. The "property rights move-

ment'' and the Republican "Contract with America" aroused broad grassroots opposition towards government regulations over the use of private land. Restrictions on building or rebuilding along hazardous coastal shorelines have been a particular area of controversy. Property rights organizations such as the Fire Island Association (New York) have argued strenuously that no limits on coastal building should be imposed without compensation to the private landowner. They and other property rights groups successfully blocked amendments to the National Flood Insurance Act that would have mandated minimum setbacks for new and rebuilt structures along eroding shorelines, as recommended by a 1990 report of the National Research Council (1990). After passing the House of Representatives by a vote of 388 to 18 in 1991, the measure never reached the Senate floor due to property rights lobbying. The 1994 NFIP amendments simply called for further study of coastal erosion (P.L. 103-325, sec. 577).

Property rights advocates have also sought to enlarge the scope of compensation for "regulatory takings" in several recent Supreme Court decisions. Their argument is based on the fifth amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which states in part: "nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation." Since the 1920s, it has been recognized that occasionally public regulations may "go too far" and amount to a "taking" of the value of property, for which compensation should be paid. Generally, where a regulation clearly is supported by a valid public purpose, such as preventing flood losses, it is upheld regardless of its impact on property values.

In 1987, the property rights movement gained a halfhearted decision from the U.S. Supreme Court relating to a flood disaster. First English Lutheran Evangelical Church v. County of Los Angeles (107 S.Ct., at 2378, 1987) involved a county moratorium on rebuilding of a camp for handicapped children in a canyon after a flash flood swept through the area. A 5-4 majority sustained a theory of "inverse condemnation" which allows an owner to recover monetary damages for loss of value during the time a restriction is in effect, if the restriction is held to be invalid. The Court did not decide whether the Los Angeles County moratorium was in fact a taking and remanded the question to the California Court of Appeals, which ruled that it was not and vigorously upheld the county's challenged moratorium: "If there is a hierarchy of interest the police power serves-and both logic and prior cases suggest there is then the preservation of life must rank near the top. Zoning restrictions seldom serve public interests so far up on the scale. . . . The zoning

regulation challenged in the instant case involves this highest of public interests—the prevention of death and injury. Its enactment was prompted by the loss of life in an earlier flood. And its avowed purpose is to prevent the loss of lives in future floods" (258 Cal. Rptr., at 904, 1989).

In 1992, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council (112 S.Ct., at 2886, 1992) that a regulation that removes virtually all of the value of property may require compensation as a "taking" regardless of the purpose of the law. Under the 1988 South Carolina Beachfront Management Act (Act 634), which prohibited new building seaward of an erosion setback baseline, Lucas was denied permission to build on his two oceanfront lots. Lucas did not challenge the validity of the Beachfront Management Act per se but claimed that its application to his lots destroyed all of their value. The trial court agreed and ordered the state to pay Lucas $1.2 million as compensation (Platt, 1992, 1996).

After the South Carolina Supreme Court (404 S.E.2d, at 895, 1991) reversed the trial court, the U.S. Supreme Court accepted Lucas's appeal from the state decision. The resulting national attention attracted numerous "amicus curiae" briefs by interested parties on both sides of the issue. Its potential importance was reflected in an editorial in the Boston Globe (March 5, 1992): "The case has far-reaching implications for the enforcement of regulations concerning everything from billboards to wetlands, as well as the coastline. Environmentalists fear that if the court decides in Lucas' favor, virtually every environmental restriction placed on the use of property will be considered a taking, thus making environmental protection too expensive" (p. 14).

The U.S. Supreme Court reversed the state ruling in a 6-3 decision, holding that where a regulation "denies all economically beneficial or productive use of land" (112 S.Ct., at 2893, 1992), it is a compensable taking. The majority opinion held that the need to compensate for "total takings" could not be avoided by merely reciting harms that the regulation would prevent, except in the case that a regulation merely reflected a state's "background principles of nuisance and property law" (Id., at 2901). Subsequently, the state supreme court on remand held that the Beachfront Management Act did not fall under that exception and that Lucas should be compensated for the period during which his land was restricted. (The state subsequently sold both of the Lucas lots to recoup its expenses, and a large house has been built on one of them, which in 1996 was threatened by renewed erosion!)

Dolan v. City of Tigard, Oregon (114 S.Ct., at 2309, 1994) involved a property owner's challenge to several requirements imposed by the city as conditions for approval of a permit to enlarge an existing hardware store. The owner was required to donate a portion of her property lying in the 100-year floodplain, plus an additional strip to be used as part of a public bikeway system. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed the Oregon Supreme Court in another 5-4 decision and held these conditions to be invalid takings due to a lack of "rough proportionality" between the burden upon the property owner and the benefit to the public: "No precise mathematical calculation is required, but the city must make some sort of individualized determination that the required dedication is related both in nature and extent to the impact of the proposed development" (114 S.Ct., at 2329-2330). The court was primarily interested in the demand by the city that public access by means of a bikeway be allowed by the property owner without compensation. The floodplain restriction was not discussed. It is not clear whether the court meant to apply the "rough proportionality" test to floodplain management regulations.

However, as with Lucas, the political importance of Dolan transcended its narrow legal significance. Justice Stevens observed in dissent that "rough proportionality" is difficult to satisfy in relation to such statistically uncertain phenomena as flooding and traffic congestion. In language calculated to raise the spirits of planners and floodplain managers, Stevens declared: "In our changing world one thing is certain: uncertainty will characterize predictions about the impact of new urban developments on the risks of floods, earthquakes, traffic congestion, or environmental harms. When there is doubt concerning the magnitude of those impacts, the public interest in averting them must outweigh the private interest of the commercial entrepreneur" (114 S.Ct., at 2329). With a change of one vote, this statement would have been the majority opinion and the law of the land.

In addition to challenges to land use regulation in the courts, property rights advocates have attempted to pass legislation that would permanently constrain takings by governmental action. Between 1990 and 1996, 18 states adopted takings legislation, while efforts to pass bills failed in 30 other states. These laws fall into two categories: assessment laws and compensation laws. An assessment law typically requires all governmental actions, or a select group of them, to be reviewed for potential impact on private property prior to implementation. The reviews, called "takings impact assessments," are in theory equivalent to

the judicial review undertaken through inverse condemnation suits, but occur before rules and regulations are adopted and implemented. These laws are expected to have a "chilling" effect on more restrictive governmental actions in order to avoid invalidation. Compensation bills, which have been adopted by four states, go a step farther. If land use rules or regulations will diminish the fair market value of property by a specified percentage (usually ranging between 10 and 50 percent), property owners must be compensated before the rule or regulation takes effect (see Freilich and Doyle, 1994). Whether the rush to limit land use regulation through legislative means will continue or abate is uncertain.

DISASTER ASSISTANCE: CAN MITIGATION STEM THE TIDE?

Although floods are involved in about 90 percent of natural disasters in the United States, the National Flood Insurance Program has by no means succeeded in its goal of shifting the costs of floods from taxpayer-funded disaster assistance to premium-based flood insurance. Outlays for federal disaster assistance, which follow presidential disaster declarations, have risen from a paltry $5 million appropriated in the original 1950 Federal Disaster Relief Act to several billion dollars annually in the 1990s. Outlays from the Disaster Relief Fund accounted for 80 percent of the $5.4 billion in payments made by FEMA in fiscal year 1994 (U.S. Congress, General Accounting Office, 1995, p. 2). But outlays from the fund comprise only an indeterminate fraction of total federal disaster-related assistance provided each year. Approximately 30 federal programs of various types offer some form of disaster service or funding (Congressional Research Service, 1992, p. 11). Twenty-six federal departments and agencies perform disaster response functions (plus the American Red Cross) as part of the Federal Response Plan coordinated by FEMA (FEMA, 1992b).

Federal assistance to public and private disaster victims after a presidential declaration is largely in the form of grants funded by the nation's taxpayers. The Bipartisan Senate Task Force report on Federal Disaster Assistance estimated that federal disaster-related expenditures from 1977 through 1993—those devoted to preparedness, emergency response, recovery and mitigation (including structural flood control projects)—totaled about $119 billion (U.S. Senate Task Force on Funding Disaster Relief, 1995, p. viii). Of that amount, direct grants to communities and individual victims, including but not limited to the Disaster Assistance

Program, amounted to about $64 billion. The remainder, approximately $55 billion, occurred in the form of low-interest loans and insurance payments. For those outlays, the actual tax cost, after considering repayments of loans and payment of insurance premiums, is represented by the amount to which the federal government subsidizes insurance premiums, issues loans at subsidized rates, or forgives loans (i.e., does not require them to be repaid).

To stem the ever-rising tide of federal disaster assistance, hazard mitigation has been increasingly advocated. As discussed previously, hazard mitigation has long been employed on a national level to protect against floods. The 1974 federal Disaster Relief Act initiated a procedure for assessing all natural hazards following a disaster declaration in which "the state or local government shall agree that the natural hazards in the areas in which the proceeds of the grants or loans are to be used shall be evaluated and appropriate action shall be taken to mitigate such hazards, including safe land use and construction practices" (P.L. 93488, sec. 406; renumbered sec. 409 in P.L. 100-707). The Office of Management and Budget in 1980 charged federal agencies under the leadership of FEMA to prepare post-disaster assessments of options for mitigating future flood losses. To comply with these mandates, FEMA formed interagency hazard mitigation teams in each federal region to prepare the required reports promptly after a disaster occurs.

The Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act in 1988 required evaluation of mitigation opportunities to accompany efforts to recover from any disaster for which funds are expended under the act. Furthermore, a variety of initiatives such as the National Earthquake Hazard Reduction Program and FEMA's Hurricane Preparedness Program seek to promote pre-disaster planning and mitigation activities at the state, local, and private levels. FEMA in 1993 established a new Mitigation Directorate, which is formulating a "National Mitigation Strategy."

However, the recommendations of hazard mitigation assessments often fly in the face of the desire of disaster-stricken communities to rebuild as quickly as possible. Rebuilding more safely may be more expensive than simply reconstructing the status quo ante. Section 404 of the Stafford Act authorized federal funding of 50 percent of the cost of mitigation projects, up to a maximum of 10 percent of total Stafford Act funding under a particular disaster declaration. After the Midwest floods of 1993, this was amended by P.L. 103-181 to authorize 75 percent federal funding for mitigation, up to 15 percent of total disaster expendi-

tures. A supplemental appropriations bill signed July 21, 1995, provided $6.5 billion for disaster relief but a mere $5 million for start-up of the Mitigation Assistance Grant Program.

Funding for flood-related mitigation projects, without the need for a disaster declaration, was authorized in the 1994 amendments to the National Flood Insurance Act (P.L. 103-325, Subtitle D). These amendments established a National Flood Mitigation Fund (NFMF), to be financed through surcharges on NFIP policies. Grants were authorized to states and communities for preparing "flood risk mitigation plans" such as those described in Chapter 1 (Sidebar 1-2). Pursuant to such plans, grants to states and communities from the NFMF are authorized to fund up to 75 percent of the cost of proposed flood mitigation activities.

The Midwest Floods: Mitigation in Practice

The Midwest floods of 1993 offered an opportunity to apply various types of post-disaster mitigation on a massive scale. The floods prompted presidential disaster declarations covering 525 counties in nine states. Total damage was estimated to fall between $12 billion and $16 billion, with federal costs amounting to about $4.2 billion (Platt, 1995, p. 26). Flood insurance payments only accounted for $293 million, or about 14 percent of total federal costs (of which about half was for basement flooding outside floodplains). As the floodwater receded in the fall of 1993, numerous studies and conferences were conducted to assess what went wrong. Foremost among these was the report of the Interagency Floodplain Management Review Committee (IFMRC, 1994; also known as "Galloway Report" after the committee's chair, Brigadier General Gerald E. Galloway, Jr.).

This report documented that, unlike coastal disasters, the 1993 flooding in the upper Midwest disproportionately affected low-income households and individuals. A comparison of census data for the flooded areas with data for nearby upland tracts disclosed that the flood victims were on the average, older, poorer, and more likely to live in mobile homes. Homes in the flooded area frequently had "market values of less than $25,000 and often as low as $10,000 or $5,000" (IFMRC, 1994, p. 7). Many of the victims were, in a sense, trapped; they lived in the floodplain out of economic necessity rather than by choice.

Before final publication of the Galloway Report, Congress in December 1993 acted to lessen future vulnerability by acquiring chronically flood-prone properties and helping their occupants relocate to safer areas (P.L. 103-181). Altogether FEMA bought out about 8,000 properties in nine states, at a total cost of more than $150 million.

Thousands of miles of nonfederal levees were breached or overtopped despite valiant efforts to defend them with sandbagging in many locations. However, as mentioned earlier, the Corps of Engineers reported that "all federally funded flood storage reservoirs operated as planned during the 1993 flood" and prevented $19.1 billion in losses (IFMRC, 1994, pp. 48 and 21). Corps reservoirs in the Missouri Basin stored about 18.7 million acre feet, reducing downstream flood damage on the Missouri by an estimated $7.4 billion. Corps levees on the Missouri River were estimated to have prevented another $4.1 billion in damages, primarily at Kansas City and St. Louis, where floodwalls were almost overtopped (IFMRC, 1994, p. 21).

Environmentalists and others maintained that future flood levels would be lower if nonfederal levees were either eliminated or allowed to fail in a large flood, and if substantial areas of floodplain drained for agriculture were allowed to revert to natural wetlands. The Galloway Report took issue with the argument that "flooding would have been reduced had more wetlands been available for rainfall and runoff storage" (p. 46). Modeling of the effects of wetland storage in four representative small watersheds indicated that "maximum reduction for floodplain wetlands was 6 percent of the peak discharge for the 1-year event and 3 percent of 25- and 100-year storm event[s]" (p. 47). Based on these findings, the committee concluded that "upland wetlands restoration can be effective for smaller floods but diminishes in value as storage capacity is exceeded in larger floods such as the Flood of 1993. Present evaluations of the effect that wetland restoration would have on peak flows for large floods on main rivers and tributaries are inconclusive" (p. 47).

On the subject of land use planning and regulation, the Galloway Report was politically cautious: "land use control . . . is the sole responsibility of state, tribal, and local entities. . . . The federal responsibility rests with providing leadership, technical information, data, and advice to assist the states" (p. 74). Despite this reluctance to endorse land use regulation in flood hazard areas, the report provided a balanced review of both structural and nonstructural issues pertaining to the recovery process.

The Oakland Fire: Rebuilding for Disaster

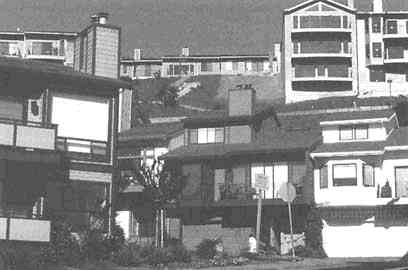

Despite all the emphasis on mitigation of multiple hazards in recent years, political, social, and economic forces conspire to promote rebuilding patterns that set the stage for future catastrophe. Perhaps nowhere has this been more conspicuous than the rebuilding in the Oakland-Berkeley Hills area after the firestorm of October 20, 1991, which destroyed over 3,300 homes in a few hours and killed 25 people. Few disasters have been more predicted beforehand or more analyzed afterwards. Yet the pattern of rebuilding, while safer in certain details, is more dense and congested than before and raises the prospect of another catastrophe. The next Bay Area earthquake is expected to occur on the

The Oakland-Berkeley Hills were rebuilt after the Oakland firestorm. Despite the very small size of lots in the burned area, reconstruction of homes within the same "footprint" was permitted. A new overlay zone for the burned area, adopted by Oakland 14 months after the fire, permitted enlargement of burned structures by 10 percent and exempted any plans submitted before its date of effectiveness, regardless of the size of structures proposed. The physical results of the ordinance are visible on the hillsides of Oakland: hundreds of very large, free-standing homes of eclectic design, often standing within 10 to 15 feet of each other on tiny lots, interlaced with roadways still as narrow and twisting as before the fire (Rutherford Platt).

Hayward Fault at the foot of the East Bay hills, "probably the most built-on fault in the world" (BAREPP, no date). About 1.2 million people live within the epicentral region of a potential 7.0 tremor on the Hayward Fault, ten times the population of 130,000 within the area affected by Loma Prieta (USGS Working Group, 1990, p. 4). The Hayward Fault has not seriously adjusted since 1868 and is estimated to have a 30 percent probability of a major earthquake in the next 30 years. Ground shaking in the East Bay would be at least 12 times worse in a 7.0 magnitude Hayward Fault earthquake than occurred there due to Loma Prieta (U.S. Geological Survey, 1994).

The Oakland fire of October 19-20, 1991, erupted under textbook conditions. Daytime temperatures hovered around 90°F and relative humidity was 17 percent. Hillside vegetation was bone dry. Dead plant material littered the ground and trees overhung many homes despite the long drought and warnings of fire danger. Hot, dry Santa Ana winds blew from the east on the morning of the conflagration. The California Department of Forestry had issued a "red flag" warning of potential fire hazard, but few residents took notice.

The conflagration began with a small brush fire. About 790 houses burned in the first hour after it began to spread. Turbulent winds generated by the fire itself spewed burning material in all directions. The fire crossed an eight-lane highway (Route 24) and continued to consume homes and vegetation further downslope. Public orders to evacuate were difficult to communicate in the absence of sirens. As the fire swept downslope, many tried to flee in their cars only to find it impossible to drive down the obstructed roads. Cars by the hundreds were abandoned as individuals literally ran for their lives, leaving the roads impassable to firefighters, who also soon lost all water pressure. There was little any of the victims could do at the last moment other than save themselves and whatever they could carry. Sixty years of building on the hills had created a hazard that no individual could undo. It was a classic "tragedy of the commons." All were swept up in the common peril, and personal consequences depended upon the fluke of the winds, not individual actions.

After the fire, all public officials proclaimed that the hills would be rebuilt. The option of not rebuilding but adding the burned area to the existing system of regional parks in the hills was not seriously considered. Public acquisition costs would have been sizable (estimated by the writer at about $400 million), and Oakland would have lost a valuable part of its tax base. Nevertheless, the failure to assess the economic and

environmental impacts of not rebuilding represents a major deficiency in the post-disaster recovery process. Several studies by federal, state, and regional authorities provided much advice on decreasing fire risk in the area through use of tile roofs, improved firefighting capabilities, and management of vegetation. Many of these proposals were carried out at least partially.

But the major influence on the rebuilding process was the private market, fueled by insurance payments. One year after the disaster, 3,954 claims amounting to $1.4 billion had been filed with 49 insurance companies, averaging more than $350,000 per household. Reconstruction stimulated the largest building boom in California in 1992 and 1993, creating some 11,000 construction jobs during a time of statewide recession. Despite the very small size of lots in the burned area, reconstruction of homes within the same "footprint" was permitted. A new overlay zone for the burned area, adopted by Oakland 14 months after the fire, permitted enlargement of burned structures by 10 percent and exempted any plans submitted before its date of effectiveness, regardless of the size of structures proposed. The physical results of the ordinance are visible on the hillsides of Oakland: hundreds of very large, free-standing homes of eclectic design, often standing within 10 to 15 feet of each other on tiny lots, interlaced with roadways still as narrow and twisting as before the fire.

Hurricane Andrew: The Private Insurance Industry and Mitigation

The year after the Oakland fire, and three years after Hurricane Hugo and the Loma Prieta earthquake, the insurance industry was hit with another immense loss, this time in Florida. On August 24, 1992, Hurricane Andrew struck Florida south of Miami, and two days later it made a second landfall in Louisiana. Andrew was not strictly speaking either a coastal disaster or a flood disaster: the destructive force here was wind. Some 75,000 homes and 8,000 businesses in South Florida were destroyed or seriously damaged by sustained winds of more than 120 miles per hour. A total of over 250,000 people were displaced from their homes in Florida and Louisiana. Total economic loss due to Andrew was estimated at $30 billion. Total federal disaster assistance was about $2 billion, and the private insurance industry paid about $15.5 billion on 680,000 claims. Nine property casualty insurance companies were rendered insolvent by the disaster [Insurance Institute for Property Loss

Reduction (IIPLR), 1995a]. This was at the time the largest loss from a natural disaster in U.S. history (U.S. Congress, General Accounting Office, 1993, p. 4). (The 1995 Northridge earthquake was larger.)

Contrary to experience under the National Flood Insurance Program, Hurricane Andrew caused more damage to recently built structures than to those built before 1980 (IIPLR, 1995b). This partly reflected the use of building and architectural practices that actually increased vulnerability to wind damage. And about one-fourth ($4 billion) of the insured loss was attributed to shoddy workmanship and poor enforcement of building codes (IIPLR, 1995b).

Because of Hurricane Andrew, the private casualty insurance industry in the United States assumed a more active role in promoting safe building and land use practices. In remarks to the National Mitigation Conference in December 1995, Eugene Lecomte, CEO of IIPLR, stated, ''Our mission is to reduce deaths, injuries, and property damage resulting from natural hazards—from hurricanes, earthquakes, tornadoes, floods, windstorms, hail, freezing, and urban wildfires. . . . If we can prevent building in the most hazard-prone areas, we can prevent property damage and probably eliminate many deaths and injuries. So why do we allow building on earthquake faults? On coastal shorelines where hurricanes hit? . . . All we ask is that builders in these areas acknowledge that their structures—whether homes or commercial buildings—are at greater risk and mitigate accordingly. In some cases, that may mean not building at all in the most vulnerable areas." The insurance industry's reaction may signify a new era of hazard mitigation in the United States in which the industry presses the government to do what the property rights movement has argued against: regulate private land use to reduce disaster losses.

CONCLUSIONS

Since the seventeenth century, Europe and the United States have gained considerable experience in preparing for and mitigating the effects of major natural disasters. Elements of this preparation have included: (1) recognizing a disaster as an opportunity to alter laws, policies, and practices relating to the reconstruction process; (2) considering a range of approaches to reduce vulnerability, including both structural and nonstructural measures; and (3) recognizing the limitations of technology, especially with respect to lifelines.

Disasters inevitably raise the issue of the level of responsibility in

regard to intervention to achieve mitigation—namely, who should be required to do what? The private and local levels of authority usually seek to at least rebuild the status quo ante, and preferably bigger and better. While well-intentioned efforts may seek to incorporate mitigation into the rebuilding process, the combined influence of private real estate values and municipal tax base concerns often stymie any significant changes in building patterns, as in the case of Oakland after its 1991 fire. (Even London in its 1667 Rebuilding Act prescribed more drastic replanning of the street plan than occurred in Oakland.)

Under the 1988 Stafford Act and its predecessors, the Federal Emergency Management Agency is the prime federal response agency. Mitigation has been a key element of national disaster policy and programs, as reflected most recently in the creation of a FEMA Mitigation Directorate in 1993. Yet FEMA today seeks to devolve responsibility for mitigation to lower levels of government under the rubric "all mitigation is local." Federal technical assistance and, in certain cases, funding are provided, as after the Midwest floods. But the initiative is left to nonfederal authorities to pursue mitigation efforts, even though they may conflict with the local and private interest in rebuilding as quickly as possible. As noted in the Galloway Report (p. 180), the assurance of federal assistance in the event of a repeat disaster creates a "moral hazard" by lowering the incentive to avoid risk.

In the case of flood disasters, the National Flood Insurance Program specifies more detailed federal standards for local mitigation than is the case under the Stafford Act. Yet as discussed earlier, land use planning and management have been subordinated to building and elevation requirements. Even in highly hazard-prone floodways and coastal areas, building and rebuilding are generally allowed under NFIP standards, and flood insurance coverage is available to the mean high-water line along tidal coasts, with the cost contingent upon elevation. This in turn obligates the private insurance industry to provide wind and comprehensive coverage to homes in hazardous locations. According to the Insurance Institute for Property Loss Reduction (1995b, p. 2), total privately insured property exposure values (not including the NFIP) in coastal counties increased by 69 percent between 1988 and 1993, from $1.86 trillion to $3.15 trillion (although much of this coverage applies to property not situated directly on the coast).

Certain states impose stricter requirements than the NFIP, such as Florida and North Carolina in regard to coastal erosion zones, and Illinois regarding 100-year floodplains. But the growing influence of the

property rights movement, discussed in this chapter, may undermine the viability of such prudent limitations.

Thus, the issue of the appropriate scale of intervention seems to be an "Alphonse and Gaston" situation where each level of authority looks to the others to take leadership, provide funding, and accept the legal and political heat for prescribing unpopular or costly mitigation initiatives.