Cooperating with Nature: Confronting Natural Hazards with Land-Use Planning for Sustainable Communities (1998)

Chapter: 3 Governing Land Use in Hazardous Areas with a Patchwork System

CHAPTER THREE

Governing Land Use in Hazardous Areas with a Patchwork System

PETER J. MAY AND ROBERT E. DEYLE

AT THE HEART OF THE THORNY problems posed by management of land subject to natural hazards lies a central conflict in public policy goals. On the one hand there is the goal of promoting economically beneficial uses of land, and the accompanying desire to allow individuals free use of their property, unimpeded by governmental intervention where possible. But these goals often conflict with the goal of promoting public safety and the welfare of the larger community through land use management policies that protect against the destructive effects of floods, coastal storms, earthquakes, landslides, and wildfires.

There are strong incentives to permit and even promote economically beneficial use of land despite the presence of natural hazards. The land may have significant value as residential real estate, or as rich, riverine floodplains, or as important commercial access to resources or navigation. Moreover, there is a reluctance to constrain or prohibit land use when areas are already in private ownership or have already been developed in economically beneficial ways.

On the other hand, private owners of land vulnerable to natural hazards may put their land to use in a

way that threatens public safety. Some argue that government is obliged to protect individuals from their unwise land use decisions, or to protect their neighbors from the effects of those decisions as, for example, when filling floodplain land in one area results in increased flood risk or destruction of valued wetland habitats downstream. Still others maintain that it is inequitable for governments to subsidize land use in hazardous areas through public financing of emergency management and disaster response programs, or through public maintenance of the infrastructure that serves those areas.

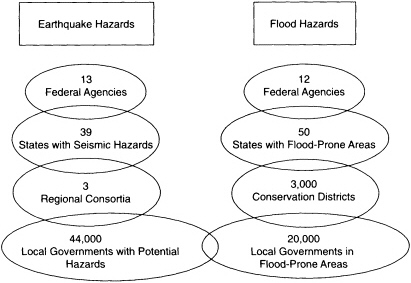

In addition to the choices posed by these conflicting goals, policymakers must also decide upon the appropriate roles of different levels of government in land use and development management. At the heart of this choice are issues of the ability and willingness of different governmental levels to undertake such management. State governments delegate most decisions about land use to local governments, although federal and state interests in reducing disaster losses and minimizing relief payments in the aftermath of disaster provide a compelling rationale for higher-level government involvement. Relationships among different levels of government involved in land use management are complex, with a number of governmental levels and agencies sharing responsibility in relation to various hazards. Figure 3-1 illustrates these relationships with regard to earthquake and flood hazards.

As discussed in Chapter 2, the federal government has assumed increasing responsibility for financing structural protection against natural hazards and supplementing state disaster-relief efforts. States also have assumed a sizable burden of the nonfederal share of the costs of disaster response and recovery. Generally, federal and state governments over the past two decades have become increasingly involved in directly regulating land use and in influencing land use decisions by local governments.

The various choices made by the federal and state governments in attempting to influence land use and development in hazardous areas are reflected in a diverse set of policies and programs. Most of these are aimed at influencing the ways in which local governments regulate land use or development. The various policies and programs resemble a house that has been subjected to numerous cosmetic fixes and redesigns over the years. Different owners and architects have added their perspectives on what would make it more livable. New additions have been appended to the old structure to accommodate changing demands or preferences and different ideas about what constitutes good design. As a

FIGURE 3-1 Relationships among different agencies and levels of government can be complex when they share responsibility regarding earthquake and flood hazards. Some government levels have jurisdiction over areas that are both earthquake- and flood-prone. Sources: Federal Interagency Floodplain Management Task Force (1992); Federal Emergency Management Agency (1994c).

consequence, the system is awkward and inconsistent in design, and many of its parts do not function well. The house is better thought of as a set of overlapping structures than the product of any grand design.

In recent years there has been increasing criticism of the patchwork of federal and state policies and programs governing local decisions about land use and development. Concerns about the costs imposed by the patchwork—both compliance costs and lost income caused by delayed or restricted development—have given way to a much stronger reaction expressed as a movement to protect private property rights. In addition to these criticisms, the hodgepodge of land use policies and programs is now being measured against a new standard—environmental sustainability. The critical test is whether the system helps the private sector and local governments make choices about development and growth that ensure long-term maintenance of a desired quality of life. Fostering sustainability fundamentally challenges intergovernmental policy design; it requires examination of the complexities of human interaction with

the natural environment over the long-term, and consideration of the cumulative effects of development on air, land, and water, and among different jurisdictions. Such an examination also raises issues about the appropriate spatial and temporal scales of planning and policy making.

This chapter discusses the choices faced by various levels of government and the resultant intergovernmental patchwork of policies and programs governing land use and development in hazardous areas. The primary focus is the intergovernmental system as it relates to decisions that the private sector and local governments make about land use and development. We also look at the motivations and interests of different levels of government, potential conflicts among and within these levels, and the implications for the design and implementation of natural hazards policies.

LOCAL GOVERNMENTAL CHOICES: RELUCTANCE TO ENACT STRONG LAND USE MEASURES

If people chose not to locate in hazard-prone areas, the problems posed by development would be greatly diminished. However, the reality is that certain types of hazardous areas are often among the most desirable for development. Moreover, development of these areas has been made possible by engineering advances that allow building on steep hillsides and in areas with poor soils; by construction that is more resistant to wind, flooding, and earthquakes; by protective works that limit risks posed by flooding and coastal storms; and by risk-sharing mechanisms such as federally sponsored flood insurance and federal disaster assistance programs that reduce the private risks of developing hazard-prone areas. Given these factors, landowners and developers are unlikely to alter their preferences for development of such land without prodding.

Such prodding might be expected from local governments, but it is not a simple matter to put in place a set of rules that balance desires for development with needs for protection of life, safety, property, and environmental quality. Achieving this balance often pits powerful forces against each other (see Logan and Molotch, 1987). Various studies point to the reluctance of local governments to adopt, or adequately enforce, strong measures for managing land use and development in hazardous areas. National studies of risk reduction measures by Berke and Beatley (1992b), Burby and French et al. (1985), Godschalk et al. (1989), and Wyner and Mann (1986) document noteworthy gaps in local policy

adoption of land use measures for reducing risks posed by earthquakes, floods, and coastal hazards.

Local governments are often reluctant to adopt such policies for a variety of reasons. First, like individuals, unless governments have direct experience with the devastation wrought by a natural disaster, they tend to discount the risks involved in allowing development in hazardous areas. Second, even in relatively high-risk areas where losses have already occurred, other problems are often higher on local agendas. Third, hazard-prone areas often are very valuable economic resources because of natural amenities such as open topography, view, ocean frontage, and access to water and water-based transportation. Finally, because hazard-prone areas often are already built out, remedial actions for addressing hazards are costly to implement and politically difficult. As a consequence, local governments are typically reluctant to take strong steps to regulate land use and prefer other hazard mitigation mechanisms such as structural protection or strengthening existing buildings. Federal programs reinforce this preference by allowing costs to be shifted from local taxpayers to the federal treasury.

Two factors are key to local governments' use of strong land use planning and development management programs for hazard mitigation. Of prime importance is the commitment of local officials to manage development in hazard-prone areas. The willingness of local elected officials to advocate such measures is an essential ingredient to local governmental action, and their reluctance to do so serves as a key impediment. Also relevant, but generally found less of a constraint than commitment, is the capacity of local governments. While lack of resources and technical expertise can impede such programs, shortfalls in capacity are generally not an insurmountable barrier in larger jurisdictions, with the notable exception of building code enforcement (see Federal Emergency Management Agency, 1992c, pp. 74-76; Berke and Beatley, 1992b, p. 94). The importance of commitment and capacity is documented in a number of studies, but stands out most clearly in work by planning scholar Raymond Burby and his colleagues on local planning for hazard mitigation (see Burby and May et al., 1997; Dalton and Burby, 1994; May et al., 1996). One clear implication of this line of research is that the willingness of local governments to undertake risk reduction programs has more to do with community resources and the extent of local political demands, which affect the commitment of elected officials, than with previous experience with disasters or objective risk.

Clearly there are constraints on the ability to reduce the risks of

natural hazards through land use planning and development management. The existing patterns of development and the nature of the hazard limit the appropriateness of different planning tools. A community in which a large amount of land is susceptible to severe risks is much less able to use land use tools to steer development to safer land. Also, communities with large areas already developed will be less able to apply land use measures as a primary mitigation tool.

Studies of post-disaster recovery further demonstrate the reluctance of local governments to significantly restrict land use in hazardous areas even when the risks of such land use have been vividly demonstrated (Haas et al., 1977; Rubin et al., 1985; Rubin and Popkin, 1990; Smith and Deyle et al., 1996). After a disaster, local governments tend to focus on returning to normal as quickly as possible. Where there is an attempt at planning the post-disaster recovery process, the focus is typically on improving the community by enhancing its economic viability. Mitigation measures—either structural alterations to the environment (dams, levees, etc.) or strengthening of the built environment—are often employed to protect against future hazards. Radical changes in land use are rarely attempted and even less frequently accomplished. There have been few instances where a post-disaster recovery plan was in place prior to a natural disaster.

FEDERAL CHOICES GOVERNING STATE AND LOCAL ACTIONS

The federal government has a strong interest in reducing disaster outlays by promoting land use and development measures that reduce exposure to hazards. However, the federal government depends on local government to put hazard mitigation measures in place, and local governments have been reluctant to play this role (more generally, see May and Williams, 1986). The states may be able to resolve this impasse by acting as intermediaries in bringing about local action. In this section, we consider federal choices and influence.

Federal (and state) policymakers can make use of a variety of interventions to influence land use and development (see Table 3-1). Generally, these interventions fall into two categories: direct and indirect involvement. Higher levels of government can act directly to regulate land use and development, or they can attempt to influence development directly by investing in real property or infrastructure. Acting more indirectly, higher levels of government can influence decisions of lower-level

TABLE 3-1 Federal and State Choices for Influencing Land Use and Development

|

Direct Intervention |

Indirect Intervention |

Incentives and Information Overlays |

|

Land use regulation |

Planning mandates |

Financial assistance |

|

Investment in land or infrastructure |

Regulatory mandates |

Technical assistance Education and training Information |

governments by imposing planning requirements or other mandates. Other policy tools include the use of various incentives (e.g., funding, technical assistance), information (e.g., maps of hazardous areas, risk profiles), and education and training.

The Federal Patchwork of Programs

A plethora of federal programs attempt to influence decisions by the private sector and local governments about land use in hazardous areas. Direct federal regulation of land use has been limited to the protection of wetlands and endangered species, and has had only limited impact on reducing the risks of natural hazards. For some hazards, the federal government has employed regulatory mandates and incentives to prod local governments to initiate controls over land use and development, or to at least analyze the hazards presented by development. For other hazards, the federal government has used investment and incentive strategies to influence private sector development behavior. In still other cases, federal influence has been limited to the provision of technical information or financial support for planning or development management by states or local governments.

With the exception of wetlands permitted under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act (P.L. 95-217; U.S. Code, vol. 33, sec. 404), the related "swampbuster" provisions of the 1985 Food Security Act (P.L. 99-198; U.S. Code, vol. 16, sec. 3821), and the restrictions on habitat modification under the Endangered Species Act (P.L. 93-295; U.S. Code, vol. 16, sec. 1534), the federal government has avoided direct regulation of land use. Wetlands regulations, in fact, are grounded in the federal government's authority to regulate navigation under the interstate commerce

clause of the Constitution (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3) rather than any explicit intent or authority to regulate land use (see Ferretti et al., 1995, p. 12-139). One could argue that restrictions on wetland development have reduced exposure to flood hazards where the flood storage capacities of wetlands have been preserved in riverine floodplains and in coastal areas at risk from hurricane-driven storm surges. However, such impacts were not the principal focus of the legislation and do not accrue from the protection of all types of wetlands.

Provisions under the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 that require local governments to adopt building codes for floodproofing and elevation of habitable structures constitute a regulatory mandate. These provisions were strengthened with the enactment of the Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973 which requires communities to adopt the specified regulatory measures in order to be eligible for federal aid, including disaster assistance for flood damages, loans for rebuilding after disasters, and eligibility for federal flood insurance. As noted in Chapter 1, these incentives served to induce much greater participation in the federal flood insurance program than was the case prior to their imposition. By 1978, over 85 percent of the local governments in the nation with designated flood hazard areas were participating (Petak and Atkisson, 1982). Although the program has had an important impact in stimulating local action, rather than emphasizing restriction of development (outside of the floodway itself), the emphasis has been on construction standards. Some observers (e.g., Burby and French, 1981; Platt, 1987) argue that this emphasis, coupled with the availability of relatively low-cost flood insurance, has encouraged floodplain development.

Since the late 1980s, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has offered incentives under the Community Rating System to encourage greater local effort to avoid development of floodplains. Local risk reduction initiatives that exceed the minimum requirements under the Flood Insurance Act—such as more extensive regulation of flood hazard areas, mapping, public information, and flood damage reduction—can result in lower flood insurance premiums for property owners. While participation and hazard reduction have been modest, community effort to mitigate flood hazards has been recognized with this program.

Executive Order 12699, issued January 5, 1990 (3CFR, 1990 comp., p. 269), is an example of federal leadership in hazard mitigation. In an attempt to call attention to seismic issues in new construction, the executive order requires that new buildings constructed and leased by the federal government comply with appropriate seismic design and construc-

tion standards. It also requires federal agencies that are responsible for financing new construction (i.e., through federal loan or mortgage insurance programs) to develop plans for using appropriate seismic measures in construction.

The Coastal Barrier Resources Act (CBRA) (P.L. 97-348; U.S. Code, vol. 16, sec. 3503), enacted in 1982 and revised in 1990, employs a mix of investment and incentive strategies for regulation of development on coastal barrier islands. The act designates coastal areas as ineligible for federal subsidies for growth-inducing infrastructure such as roads, bridges, water, sewer systems, and protective works. In addition, new development within such areas is ineligible for federal flood insurance. While CBRA has accomplished the objective of reducing federal financial exposure to the risks posed by coastal hazards, the act has had limited success in actually deterring development (Godschalk, 1987; U.S. Congress, General Accounting Office, 1992). Development has continued in some coastal barrier islands with private financing, especially of high-valued projects such as multi-story condominiums.

Other federal programs operate indirectly to influence state and local policy on land use and development in hazardous areas. The Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 (P.L. 92-583; U.S. Code, vol. 16, sec. 1451 et seq.) declared a national policy favoring better management of coastal land and water resources and authorized coastal states to develop and implement coastal zone management plans (Godschalk, 1992). To encourage states to prepare management plans for the coastal zones, the act offered incentives including federal funding for the design and implementation of federally approved plans. It also granted states the power to review federal actions occurring within the designated state coastal zones. State plans were required to address nine areas of declared national interest, two of which concern natural resource protection and hazard management. As noted by Godschalk (1992), the $696 million invested in the coastal program over its first 14 years had a substantial impact, motivating 29 states to design and carry out coastal management efforts. But because several basic aspects of the coastal plans are subject to state determination (e.g., the definition of the coastal boundaries, permissible uses, intergovernmental roles), there is considerable variation in approach from state to state. Moreover, the voluntary nature of the program leaves room for considerable variation in overall state effort.

Planning is also required under provisions of the Stafford Act of 1988, which amended the 1974 Disaster Relief Act. States are required to prepare and implement ''Section 409" hazard mitigation plans as a

condition for receiving disaster relief grants or loans. The plans must include an evaluation of the options for mitigating the natural hazards that threaten designated areas in the state, and must be revised following disasters that qualify for presidential declarations. The Federal Emergency Management Agency considers the status and implementation of these plans when evaluating a state's application for disaster assistance. However, local government participation in this process is at the behest of the responsible state; there are no explicit incentives for local governments to consider the provisions of the state plans in their own comprehensive planning. Reviews of these state plans have generally been critical of their failure to tie the nature of the problem to stated goals and objectives, to identify priorities in hazard mitigation, and to adequately relate priorities to implementation strategies (Deyle and Smith, 1994; Godschalk, 1995).

Other federal programs employ a mix of incentives, information, and education to influence local decisions about land use and development in hazardous areas. With regard to earthquakes, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, in conjunction with the Building Seismic Safety Council, a nongovernmental organization, has encouraged the development of earthquake-resistant construction standards and seismic standards for lifelines. FEMA has provided technical and financial assistance for federal-state partnerships for fostering stronger earthquake-preparedness efforts. The U.S. Geological Survey has attempted to mobilize local planning and response efforts by documenting seismic risks in urban areas and developing tools that local governments can use in their land use planning.

In sum, a wide range of federal programs addresses land use and development in hazardous areas. The federal government plays a direct regulatory role in wetlands protection. Through the Coastal Barrier Resources Act the federal government uses investment policies to deter development of hazardous coastal areas. With regard to earthquake and flood protection, the federal government does not intervene directly but attempts to induce state and local governments to carry out national objectives. The National Flood Insurance Act, for example, offers the incentive of affordable flood insurance as an inducement for communities to regulate development in floodplains. The Stafford Act of 1988 was enacted to bring about a more comprehensive and coherent approach to achieving mitigation of a number of natural hazards. Yet, the resulting effort—like previous efforts to provide integrated approaches—has encountered obstacles such as lack of standards for planning, cumber-

some bureaucracy, and the indifference of states and localities, or their inability, to engage in the desired planning processes.

The Legacy of the Federal Patchwork

Several key points can be made about the diverse federal programs and policies that relate to the management of natural hazards. First is the patchwork nature of federal programs and policies. No overarching federal policy governs land use and development in hazard-prone areas. Instead there are individual initiatives such as the Coastal Zone Management Act addressing development in coastal areas; the Coastal Barrier Resources Act addressing development on designated barrier islands; the National Flood Insurance Act addressing development in flood-prone areas; Section 404 of the Clean Water Act and the "swampbuster" provisions of the 1985 Food Security Act addressing development in wetlands; various disaster-relief provisions of the Stafford Act that open opportunities for mitigation in the aftermath of major disasters; and several technical and financial assistance initiatives concerning seismic hazards. In total, there are over 50 federal laws and executive orders that relate to hazard management (Federal Interagency Floodplain Management Task Force, 1992).

Secondly, land use provisions are often the weak elements of federal programs; they are the provisions that are given low priority, are ignored and unfunded. The Coastal Zone Management Act allocates funds to states for developing plans for managing growth in coastal areas, but for most states participating in the program, planning for natural hazards has taken a back seat to other goals such as accessibility and environmental quality. The Water Resources Development Act of 1974 requires the Army Corps of Engineers to consider nonstructural alternatives to prevent or reduce flood damages (P.L. 93-251), but this provision largely has been ignored (Burby and French et al., 1985). The National Flood Insurance Act included land use planning provisions, but these were never implemented.

A third key point is that the net effect of federal programs is to encourage development in hazardous areas. For example, rather than prohibiting or restricting development in flood-prone areas (with the exception of floodways), the National Flood Insurance Program has arguably encouraged development, although development is elevated to protect against losses (i.e., from a 100-year storm). By encouraging development, the NFIP has increased the risk of losses from more severe,

Sandbags and pumps keep floodwater away from residential area, St. Genevieve, Missouri (FEMA).

less frequent storms, such as the Midwest floods of 1993. This bias toward solutions that encourage development and away from land use approaches also characterizes the current federal involvement in the reduction of earthquake hazards. As noted above, federal initiatives aimed at mitigating earthquake losses consist of a mix of developing new building code standards, providing information and education about earthquake hazards, and financing and participating in collaborative-planning partnerships. The potential for land use provisions has been overshadowed by efforts to foster stronger building codes, to encourage enactment of such codes by states and localities that do not have them, and to improve code compliance and enforcement.

A fourth key point about the federal patchwork is that a host of other federal policies can limit opportunities for local governments to use land use management tools for hazard mitigation. The largest influence by far has been the extensive construction of protective works along major rivers, first mandated by the Flood Control Act of 1917 (U.S. Statutes at Large, vol. 39, p. 948), then in the 1930s by a series of amendments to the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899 (U.S. Statutes at Large, vol. 30, p. 1121). Despite the expenditure of many billions of dollars for structural flood control measures, flooding remains a formi-

dable hazard. Moreover, like the provisions of the National Flood Insurance Act, the protective works have arguably increased the numbers of people and the amount of public and private property exposed to catastrophic flooding. The Federal Interagency Floodplain Management Task Force summed up the situation as follows: "Floodplain management should result in an actual decline in the nation's flood losses, including public and private property damage, injuries, and disaster relief. This has not been achieved. In fact, there was a definite increase in flood damages from 1916 to 1985, although there is evidence that these losses have remained fairly constant over the last two decades when compared to broad economic indicators like the GNP" (1992, p. 60). Increased exposure of people and property to flooding has been abetted by federal financing of highway construction, sewers, and other infrastructure that increase the likelihood of development in flood-prone areas while reducing development costs.

To sum up, the federal effort to date has for the most part failed to advance land use planning to manage losses from natural disasters, and to promote sustainability. The patchwork of federal programs affecting land use in hazard-prone areas has resulted in missed opportunities, notably, the failure to take advantage of land use provisions in the National Flood Insurance Program, or to make stronger land use provisions part of federal policy regarding other hazards. Moreover, a number of long-standing federal programs contain a bias against effective use of land use methods for hazard mitigation; these programs show a strong preference for protective works which in the long run increase rather than decrease the potential for catastrophic loss.

STATE CHOICES: GOING THEIR OWN WAY

With the exception of regulatory actions spurred by the National Flood Insurance Act and the planning incentives of the Coastal Zone Management Act, states have largely gone their own way in devising policies governing land use and development in hazardous areas. Not surprisingly, there has been a wide divergence in the approaches taken by states and in the extent to which they actively seek to mitigate risks. Like the federal government, states have a number of choices concerning when and how to intervene in decisions about land use and development. States can intervene directly and exert their regulatory powers over local decision making. Or states can establish planning or other processes that

require or encourage local governments to take actions in concert with state desires. Or states can choose to ignore problems posed by development in hazardous areas and leave them for other levels of government to address. As is true at the federal level, a variety of policy instruments can be incorporated into state policy.

The Range of State Programs

The choices that states have made span the full range of policy approaches. Some states, such as Delaware, Florida, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, and Wisconsin, have been willing to intervene directly in private land use decisions by imposing requirements upon development of environmentally sensitive or hazardous areas such as wetlands and coastal zones. Other states have required local governments to enforce provisions of state building codes that address seismic hazards or hurricane winds. In addition, Florida, North Carolina, Washington, and others have established planning mandates, with varying levels of incentives, to prod local governments into considering natural hazards as part of comprehensive planning. A few states, such as California, Florida, Massachusetts, and North Carolina, have used their investment policies for land acquisition and public infrastructure to influence land use and development in hazardous areas.

By far the most common approach chosen by states is direct regulation of selected areas (e.g., wetlands) or aspects of development (e.g., coastal development). This entails state promulgation of rules governing land use or development for the particular situation, and state responsibility for enforcing the rules (which may be delegated to local governments). For example, Godschalk et al. (1989) report that all 18 hurricane-prone coastal states have enacted some type of direct state regulation regarding beach erosion, wetland areas, or sand dunes. At least 13 states now impose various coastal setbacks, requiring new development to locate a certain distance inland from the shoreline. Similarly, California has a requirement that no structures for human occupancy can be placed within 50 feet of a defined earthquake fault. In addition, many states have established special regulations governing development near sensitive areas such as wetlands (see Kusler, 1980).

More than a dozen states have enacted mandates that require local governments to develop comprehensive land use plans. The states specify policy goals and objectives but, to varying degrees, leave the specific details of the content and implementation of plans to local governments.

The state programs vary in the extent to which they identify problems posed by development in hazardous areas to be considered in the local planning process. As noted by Burby and May et al. (1997), there are three basic arguments for the comprehensive-planning approach. First, in some states local governments have shown a willingness to grapple with land use problems and are prepared to work as partners with state governments in addressing these problems. Second, the emphasis on comprehensive planning recognizes the interrelated character of land use decision making and other aspects of community development. A third argument is that comprehensive-planning programs can overcome shortcomings that sometimes characterize direct state regulation of land use or development. These shortcomings or obstacles include inefficiencies inherent in uniform state standards, objections to state control over local decisions, gaps in piecemeal approaches, and difficulties in monitoring and enforcing state standards.

California has mandated local planning since 1937, but it was not until 1972 that California required local governments to consider natural hazards in their planning. Subsequent development of state planning mandates has occurred in two waves. In the 1960s and early 1970s the California mandate was revised, and new programs were established in

These houses on pilings survived a nor'easter in Scituate, Massachusetts, 1991 (Ralph Crossen, Building Commissioner, Barnstable, Mass.).

Florida, Hawaii, Oregon, and Vermont. Also at this time, planning requirements for selected substate areas were mandated in Colorado (unincorporated areas of counties), Massachusetts (Cape Cod Commission, Martha's Vineyard), New Jersey (Pinelands area), New York (Adirondack Park), and North Carolina (coastal counties). The second wave of planning mandates began in the mid-1980s and included major revisions to planning requirements in Florida and Vermont, and the institution of new state mandates in Delaware, Georgia, Maine, Maryland, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Washington.

States have also employed a mix of incentives and informational and educational approaches to influence local decisions about land use and development in hazardous areas. One approach is to withhold funds for public facilities or other infrastructure in such areas so as to discourage development. Florida's policymakers have enacted strong legislation of this type, which substantially restricts public investment in hurricaneprone coastal areas. Other states that use variants of this general approach include Delaware, North Carolina, Massachusetts, and South Carolina (see Godschalk et al., 1989, and Deyle and Smith, 1994). States also offer incentives to local governments in the form of low-interest loans and grants for funding mitigation planning and programs. This is particularly common in the funding of flood control projects; for example, the Texas Water Control Revolving Fund is a source of funding for development of structural and nonstructural protection against floods. Florida recently initiated a matching grants program to support preparation of local hazard mitigation strategies. Many states provide information, such as maps or technical assistance, in order to enable local governments to carry out state objectives. In California, for example, the Division of Mines and Geology has produced maps of ground shaking, landslide, and liquefaction potential for some localities, and the Division of Forestry has produced wildfire hazard maps for urban areas of the state.

In sum, states, independently from federal initiatives, have developed an array of policies and programs relating to hazardous areas. There is considerable variation in the specifics of the state regulations, mandates, and other strategies that have been adopted. While most states have policies or programs that influence development within environmentally sensitive areas like wetlands, fewer states have taken initiatives that are explicitly concerned with development in areas subject to natural hazards. However patchy, there clearly has been more progress at the state level than at the federal level both in using land use measures to

manage development in hazard-prone areas and in stimulating local efforts to better manage development in such areas.

The Legacy of Divergent State Choices

Perhaps the most noteworthy point about state management of natural hazards is the diversity of choices that have been made. In studying state mandates governing hazard-prone areas, May (1994) found several reasons for state choices. State legislatures vary in their willingness to intervene in local decision making, reflecting differences in the political culture of the states. Willingness to intervene at the local level is, in turn, affected by the level of agreement among state policymakers about the seriousness of the hazards. Where agreement is strong, there is a predisposition to craft a tough statute. Another source of variation in state choices arises from within-state differences in the political power of various development and environmental interests.

Although a number of states have undertaken direct regulation of various aspects of development, there is a notable lack of systematic evaluation of those experiences. In one notable exception, a study of programs in 20 states to reduce erosion and sedimentation pollution in urban areas, Burby (1995) found a number of deficiencies in program content and performance. Chief among these, as the program administrators asserted, were low levels of staffing and funding relative to the tasks at hand. Recognizing the limited capacity of state agencies, Burby and Paterson (1993) found that local enforcement of a North Carolina program at least equaled, if not surpassed, state performance.

Planners have taken more interest in state mandates requiring local governments to undertake comprehensive planning. Dozens of articles and several books have described these mandates and the state land use management systems in which they are embedded, and have compared programs across states (for an overview, see Bollens, 1993). But, except for critical commentary about efforts of states in the 1970s to put in place comprehensive planning mandates, there has, until recently, been little assessment of the impact that these state mandates have had on local government policy and land use.

A national study of state comprehensive planning mandates (Burby and May et al., 1997) reached more positive conclusions than evaluations of the first generation of state planning mandates. By comparing the actions of local governments in states that have imposed planning mandates with the actions of local governments in states that have not

imposed such mandates, Burby and his colleagues show that the planning mandates have stimulated local government efforts to plan for and manage development in hazard-prone areas. Local governments are more likely to prepare comprehensive plans when required to do so, and state planning mandates foster a substantial improvement in the quality of plans and their attention to natural hazards. For states that require comprehensive plans of local governments and follow through on those requirements, local plans are more well grounded in fact, they state goals more clearly, and they propose stronger local policies for guiding development.

However, while it is better to have a state comprehensive planning mandate than not, such mandates do not guarantee local attention to hazards. In a detailed study of the degree to which local plans comply with Florida's planning mandate, Deyle and Smith (1994) found substantial variation. Policy choices made by the state implementing agency had a significant impact on which hazard mitigation planning mandates were complied with by local governments. This study also documents substantial tolerance by the state for variation among communities in their compliance with most of the hazard mitigation planning requirements.

Similar variation in local government compliance with state mandates is documented by May and Birkland (1994) in a study of earthquake policies in California and Washington State. A higher percentage of local governments in California adopted earthquake risk reduction measures than in Washington State. California has both a number of state mandates governing such actions and a history of notable earthquakes. Washington State has similar seismic potential, but less extensive earthquake experience and fewer mandates. The key finding from the study, however, is that compliance with California's earthquake-specific mandates is uneven; much slippage occurs at the stage of actually carrying out the policies. In their analysis of the data from the comparative state survey conducted by Burby and his associates, Berke et al. (1996) document substantial variation among the local plans prepared both with and without state planning mandates.

The research reviewed here on state planning and hazard reduction mandates is sobering in that it shows that such mandates, in stimulating local efforts, produce marginal rather than widespread changes. Bringing about major shifts in land use or development decision making is very difficult given existing development patterns and the entrenchment of forces for development. The influence of planning mandates varies

considerably among the states due to differences in policy design and the strength of efforts by relevant state agencies to implement mandates. By far the most important factors in enhancing local attention to these issues are strong commitment by relevant state agencies to the mandate, backed by strong implementation efforts. Florida's success in mandating comprehensive growth-management planning by local governments illustrates the importance of commitment-building incentives within mandates (e.g., threatening local governments with sanctions for failing to meet deadlines, requiring revisions of unacceptable local plans), accompanied by strong state implementation efforts.

The bottom line is that state governments have made progress in advancing local land use planning for natural hazards, but with notable gaps. The evidence is that state comprehensive-planning mandates can be useful in influencing the way local governments address development in hazard-prone areas. In particular, planning mandates draw attention away from limiting harm—for example, through hazard protection structures-toward preventing harm through management of land use. But, less than one-third of the states have chosen this route, and among those states there is substantial variation in outcomes.

CHOICES ABOUT REGIONS: THE LIMITATIONS OF REGIONAL LAND USE SOLUTIONS

One of the more challenging aspects of managing hazards is choosing an appropriate spatial scale. A strong case can be made for regional approaches, which have been advocated for the management of ecosystems, earthquake hazards, and flood hazards. Regions whose jurisdictional boundaries coincide with natural boundaries are ideal for managing natural resources and environmental conditions. This is the logic of watershed associations and river basin authorities that have been created for water resource planning and development (Platt, 1987). This kind of spatial scale is also illustrated by regional park management districts (such as the regional authorities created for managing natural resources in the Adirondack Mountains in New York State and the Pinelands in New Jersey) and regional districts for air pollution management and flood control in a number of metropolitan areas.

The United States is perhaps exceptional in the variety of forms of regional entities and special districts that have been created for dealing with such issues. The success of regional initiatives for land use planning has been limited however. A key impediment to the formation of re-

gional levels of authority, whether in the form of entirely new organizations or less formal councils or federations, is that they pose a threat to other levels of government and their constituencies. No matter how desirable it is to have regional management entities, they constitute another layer of bureaucratic intervention and their existence can provoke turf wars. Local officials see funds going to regional organizations that could be coming to them, and they are concerned with potential encroachment on local authority. Rather than easing intergovernmental relations, regional initiatives can increase the potential for conflict and for fragmenting program implementation.

Florida's experience in carving out a broad-purpose regional role in land use planning illustrates the tensions that attend regional planning and management initiatives. There was long-standing tension between local governments and the independently authorized and funded regional water-management districts. Partly to avoid exacerbating these conflicts, Florida's policymakers assigned regional planning functions under the state's 1985 growth management legislation to a different set of regional authorities, involving regional planning councils that had less power. Even though local officials hold two-thirds of the seats on each regional council (the other third are appointed by the governor), local governments resent regional interference in local affairs, just as they resent state interference. The precariousness of the regional planning function was revealed by efforts in the 1992 legislative session to abolish regional planning councils. This eventually resulted in legislation redefining their roles in order to minimize potential interference with local planning.

The experience of the federal government in creating regional entities has also been unsatisfactory. Efforts to mandate the creation of regional planning entities by lower levels of government, best exemplified by the Section 208 areawide water quality planning provisions of the 1972 Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments (P.L. 92-500, U.S. Statutes at Large, vol. 86, p. 816), have been largely unsuccessful (Deyle, 1995). The six regional river basin commissions created by the 1965 Water Resources Planning Act were never granted adequate resources to carry out their tasks (P.L. 89-80, U.S. Statutes at Large, vol. 79, p. 244). Furthermore, they were criticized for studies and plans that were too general in scope (Kusler, 1985). The Reagan administration dismantled these commissions in the early 1980s. In addition, Burby and French et al. (1985) found that regional councils did a poor job of floodplain management. After a survey of 585 regional councils, the authors concluded that most devoted relatively little of their overall staff re-

sources to management of flood hazards. The majority of such agencies performed planning, coordination, and capacity-building functions. Very few exercised direct land use regulatory powers or undertook investment strategies such as land acquisition.

The most successful examples of regional planning and management of land have been new special-purpose organizations created by federal or state legislatures with the authority to directly implement or compel implementation of their plans and policies. Regional partnerships between levels of government that are less oriented toward intervention have also been successful in facilitating planning for natural hazards. Prominent examples of regional planning and regulatory entities include the Adirondack Park Agency, the New Jersey Pinelands Commission, the Tennessee Valley Authority, Florida's water management districts, the Delaware River Basin Commission, and flood control agencies such as the Denver Urban Drainage and Flood Control District. Platt (1986) attributes the success of the regional flood control agencies to a mix of fiscal autonomy, legal flexibility in interpreting their mandates, professionalism among staff, and clear goals for the agencies. In many instances, however, the political, organizational, and environmental conditions that facilitated such initiatives were exceptional.

Less ambitious regional partnerships between federal and state governments have been successful in enhancing the capacity of lower levels of government to plan for and manage natural hazards. Examples include the Southern California Earthquake Preparedness Program and the San Francisco Bay Area Regional Earthquake Preparedness Project, which were established by the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the state of California in the 1980s to provide technical information and technical assistance to local governments. The success of these programs has led to similar initiatives elsewhere around the country (Berke and Beatley, 1992b).

Some observers have argued that fragmentation among levels of government within a federal system is a fact of life that cannot be changed. Thus, as noted by Deyle (1995), collaborative alliances among existing government entities—such as the successful Chesapeake Bay Program and the regional earthquake partnerships between the Federal Emergency Management Agency and states—are probably the best that can be achieved in efforts to integrate natural-resource and land use management on a regional scale. The function of regional entities in governing land use in areas prone to natural hazards is likely to remain limited to broad-brush planning, intergovernmental coordination, and capacity-

building functions of providing information, education, and technical assistance to local governments.

PROMISING FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The historic reluctance of federal and state governments to intervene directly in land use decisions by private property owners and the current movement toward reasserting property rights contribute to a political environment in the latter half of the 1990s that is not particularly supportive of a stronger federal or state regulatory presence in governing land use or development in hazardous areas. Given this environment, and the limited impact of previous federal, state, and regional initiatives that have relied principally or solely on incentives, investment policies, or information and education, the challenge is to identify ways to enhance the commitment of local officials to managing development without engendering such negative reactions. Many argue that future directions for environmental policy in general should include less emphasis on regulatory prescription and greater reliance on local governments as partners with state and federal governments in pursuing paths to sustainability—in other words, a more flexible form of intergovernmental policy mandate.

Various authors have written about collaborative forms of environmental management under the labels ''co-production" (Godschalk, 1992), "collaborative planning" (Bollens, 1993), "civic environmentalism" (John, 1994), and "cooperative intergovernmental policies" (May et al., 1996). Although the use of these terms varies considerably, the central thrust is to devise higher-level policies that enhance local government interest in and ability to work toward achieving policy goals. These programs may prescribe planning or process elements to be followed (a form of policy mandate), but they do not prescribe the particular means for achieving desired outcomes. Cooperative mandates use financial and technical assistance for the dual purpose of enhancing the commitment of local governments to policy goals and increasing their capacity to act. The logic behind this is that higher-level governments know that action must be taken to meet specific policy goals, but local governments are best situated for determining how to achieve those goals. Local governments are told to think seriously about the problems and their solutions following prescribed planning processes, but the specific actions are left to the local governments to determine.

Federal and state policies governing hazards are evolving in the di-

rection of more intergovernmental cooperation. The primary federal example of this approach is the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, although it has been amended over the years to add greater prescription about state actions, including attention to hazards (Godschalk, 1992). Also, after two decades of experience with the limited regulatory mandate of the National Flood Insurance Program, the pendulum is swinging the other way as federal monitoring of local floodplain management is reduced in favor of local self-evaluation, as states assume stronger technical assistance roles, and as incentives through the Community Rating System are offered for enhanced local floodplain management programs. A number of states which have recently enacted or revised comprehensive-planning mandates have sought a more cooperative approach to local land use planning and development management. These states have established collaborative partnerships in which the states mandate local government planning processes with varied degrees of prescription about the form and content of the plans. The state mandates vary in the extent of oversight by state governments and the degree of coercion that is employed to get local governments to comply with planning requirements.

Better examples of this approach can be found in other countries. The cooperative approach to hazards management is a central part of environmental management in New Zealand and hazard-management in New South Wales, Australia. New Zealand has received worldwide attention for its reform of resource and environmental management and its vision of integrated, "effects-based" environmental management. Although less comprehensive, the intergovernmental regime in New South Wales provides a noteworthy example of a shift from a heavy hand to a more flexible approach to help local governments cope with flood hazards.

A study by May and his colleagues (1996) of the experience of local governments with cooperative planning programs provides a number of relevant findings. The authors compared what they labeled as a coercive regime, found more typically in the United States (such as Florida's growth management program), with cooperative regimes such as the programs in New Zealand and New South Wales. Both coercive and cooperative forms of intergovernmental policies present dilemmas. The dilemma for coercive regimes is that in bringing about procedural compliance by lower-level governments and forcing them to pursue state initiated innovations, they may straightjacket local governments that want to develop their own innovative solutions to environmental problems. Coercive intergovernmental regimes can foster a "cookie-cutter" compliance mentality in meeting state-defined deadlines and objectives

dilemma for cooperative regimes is that, although they foster local that tends to emphasize procedural over substantive compliance. The ownership of environmental management programs, they suffer from gaps in compliance because of the reluctance of some local governments to participate or follow the prescribed planning process. Local ownership is important because it provides the constituency base for fashioning acceptable land use and development rules, thereby enhancing prospects for implementation and effective environmental management. But gaps in compliance are troublesome, both in themselves and because they are difficult to close.

This research, along with findings summarized earlier from analysis of planning mandates in the United States, provides promising directions for developing more effective federal or state frameworks for governing land use and development in hazardous areas. As noted by Deyle (1995), successful collaboration depends on a confluence of favorable environmental conditions, political will and leadership, an adequate infusion of resources, an effective convener, and sufficient time for a collaborative relationship to mature through experience, mutual learning, and the development of trust between the collaborators. Perhaps the greatest challenge in natural hazards management will be forging a common view of the appropriate policy goals between local governments and higher levels of government.

CONCLUSIONS

The variety of federal and state policies and programs attempting to influence local decisions about land use and development in hazard-prone areas has resulted in an ad hoc patchwork of land use governance. Federal efforts are limited in focus, uneven across different natural hazards, and in some cases undermine the objectives of limiting exposure of life, property, and environmental resources to damage from development of hazardous areas. States employ a greater diversity of management strategies, including greater use of direct regulation of private sector land use as well as an array of incentives, investment policies, and planning and regulatory mandates. The state and federal patchwork of programs is characterized by gaps in coverage and compliance and by missed opportunities for using land use solutions to mitigate hazards.

Another consequence of the land use planning patchwork is the fostering of uneasy intergovernmental relationships. Simply put, local governments do not like the way in which the federal and state governments

have attempted to encourage or force their attention to problems posed by natural hazards (or to other environmental issues). Many local officials perceive federal and state environmental mandates as overly prescriptive and coercive. This is a recurring theme of major studies undertaken in the past decade by the U.S. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (1993) and the General Accounting Office (U.S. Congress, GAO, 1990a, 1995). Local governments complain about the failure of higher-level governments to fund implementation, about the lack of flexibility in the required actions, and about taking the political blame for infringement on property rights.

The clear implications of the uneasy intergovernmental relationships are a divergence in policy goals and a lack of trust among different levels of government, resulting in a reluctance by local officials to fully implement federal or state policies. The local responses to many federal and state programs are often token, half-hearted compliance; delay in hopes that the higher-level programs will be altered; or in some instances outright refusal to participate. For example, when the federal government sought more state involvement in the National Flood Insurance Program, formerly a federal-to-local program, the states varied greatly in their willingness to take part (May and Williams, 1986). Illinois and other states established strong state programs, but most states mounted only a token effort, and some, such as Oregon, initially refused to establish a state program.

Closely related to the goal divergence and mistrust among different levels of government is the confusion created by inconsistencies among different policies. This occurs at two levels. First is the inconsistency among policies promulgated within a given level of government, notably the long-standing conflict between policies that promote development (e.g., flood control projects and flood insurance) and policies that seek to limit exposure to risk (e.g., regulation of wetlands and development on coastal barriers). The second level of inconsistency is that between state and federal provisions; which provisions take precedence has been an important issue in court decisions about environmental policies. When conflicts exist between regulatory statutes, the federal statute generally prevails under the interstate commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution. However, where federal programs rely on incentives and inducements, there is the potential for divergent state policies to undermine federal initiatives. For instance, although the federal Coastal Barrier Resources Act constrains use of federal funds for growth-inducing infrastructure on coastal barrier islands, states remain free to cover the shortfall with state funds.

Fragmentation of programs and inconsistencies among layers of government are not unique to natural hazards policy making within the American system. Indeed, these are common features of our federal system of government. Yet, the complexities that are introduced by these features are perhaps as strong in relation to natural hazards as in any area of policy.