Cooperating with Nature: Confronting Natural Hazards with Land-Use Planning for Sustainable Communities (1998)

Chapter: Part Three: Looking to the Future 8 The Vision of Sustainable Communities

CHAPTER EIGHT

The Vision of Sustainable Communities

TIMOTHY BEATLEY

AS WE CONVERGE ON THE twenty-first century, sustainability represents the only viable paradigm in which to place land use policy and planning, and indeed environmental and social policy more generally. What sustainability means is somewhat ambiguous and controversial, but the vision of sustainability is a powerful and compelling one. It is at once a moral statement about how we should be living on the planet, and a description of the social and physical characteristics of the world as it should be. Any discussion of land use policy and planning, then, must be placed within a broader framework of sustainability. Land use planning to reduce natural hazards is ultimately and fundamentally about promoting a more sustainable human settlement pattern and about living more lightly and sensibly on the earth. As noted in Chapter 1, the increasing severity and impact of natural disasters suggest a serious breakdown in sustainability, and that indeed we are not living in a very sustainable way on the planet.

This chapter presents a vision of sustainability in the context of the reduction of natural hazards. It begins by discussing the history of the idea and the

different meanings and definitions that have emerged over the years. Next, the chapter discusses the connection between sustainability and natural hazards and identifies recent examples of how planning to foster hazard mitigation has been tied to sustainability. This chapter then extracts and presents a series of general principles of sustainability. These principles describe what the vision of sustainability implies in more detail; it can serve as a guide to more specific local and regional initiatives. The final section discusses specific steps in planning for sustainability, as well as tools, techniques, and methods for implementing the vision of sustainability.

THE MANY MEANINGS OF SUSTAINABILITY

To many, sustainability and sustainable development are just the latest buzzwords to make their way into the planning field—another set of fashionable phrases. There is no question that planners use these terms increasingly to describe what they do and what their professional mission is. A common criticism, however, is that meanings of the terms are not immediately obvious: sustainability and sustainable development require definition and elaboration, as do terms like freedom, justice, or quality of life.

We have a sense that sustainability is a good thing (and that being unsustainable is a bad thing), but will we know it when we see it? It is likely that this ambiguity will remain with us, but, in my view, the very fact that we are questioning what is or is not sustainable and exploring what the idea means and calls for is a very positive sign. It opens opportunities for critical dialogue and serves as an important catalyst for thinking clearly and systematically about the future planners can help to bring about.

Sustainability is the root term, from which stems its use as a modifier (e.g., sustainable development, sustainable forestry). A typical dictionary definition of sustain might include the following: to keep in existence, to maintain or prolong, to continue or last. Sustainability finds many of its roots in biology and ecology and specifically in the concept of ecological carrying capacity—the notion that a given ecosystem or environment can sustain a certain animal population and that beyond that level overpopulation and species collapse will occur (see Kidd, 1992). Central, then, is the idea that certain physical and ecological limits exist in nature that, if exceeded, will have ripple effects that bring population back in line with capacity.

The meaning of sustainability is perhaps clearest when applied to renewable resources such as ocean fisheries, forests, groundwater, and soils. Terms such as optimal sustainable yield have been incorporated explicitly into, for example, U.S. fisheries management law. The growing advocacy for sustainable use of a variety of renewable resources—sustainable forestry, sustainable fisheries, sustainable agriculture—is premised on the idea that these resources can be used and harvested in a manner that allows them to renew themselves and that preserves their long-term productivity. Sustainability is also a useful concept in planning the use of nonrenewable resources, the waste-assimilative capacities of the earth, and the natural services provided by the environment (e.g., climate regulation; see Jacobs, 1991).

The use of the term sustainability in environmental planning and policy circles is relatively new. It began appearing in the literature in the early 1970s and emerged as a significant theme in the 1980s, when sustainability was embraced by such nongovernmental organizations as the Worldwatch Institute and World Resources Institute, governmental organizations such as the U.S. Agency for International Development, and a number of international study groups. The term of preference became sustainable development, which focused on how human interventions—especially international development programs and projects—failed to respect the integrity of the natural systems in which they were sited. Projects of international development agencies such as the World Bank were severely criticized as the antithesis of sustainable development.

There have been a number of attempts to define sustainable development formally, especially in the last decade. Perhaps the most frequently cited definition is that put forth by the World Commission on Environment and Development—also commonly known as the Brundtland Commission (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). The WCED defined sustainable development as that which ''meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (WCED, 1987, p. 8). More recently the National Commission on the Environment has defined sustainable development as "a strategy for improving the quality of life while preserving the environmental potential for the future, of living off interest rather than consuming natural capital. Sustainable development mandates that the present generation must not narrow the choices of future generations but must strive to expand them by passing on an environment and an accumulation of resources that will allow its children to live at least as

well as, and preferably better than, people today. Sustainable development is premised on living within the Earth's means" (National Commission on the Environment, 1993, p. 2). These definitions share an emphasis on certain important concepts and themes at a general level. They stress the importance of living within the ecological carrying capacities of the planet, living off the ecological interest (protecting the ecological capital), and protecting the interests of future generations. They envision a society that "can persist over generations, one that is farseeing enough, flexible enough, and wise enough not to undermine either its physical or its social systems of support" (Meadows et al., 1992, p. 209).

Application of concepts of sustainability to cities, towns, and settlement patterns has been an even more recent phenomenon, yet there has been an explosion of thinking, writing, and practice attempting to make this connection in recent years (e.g. see Aberley, 1994; Beatley and Brower, 1993; Blowers, 1993; Newman, 1996; Rees and Roseland, 1991; Roseland, 1992; Van der Ryn and Calthorpe, 1991; and many others). There are a variety of labels used including sustainable cities, sustainable urban development, and sustainable communities, among others (I will tend to use the latter in this chapter). All take as their beginning assumption that the current patterns and forms of urban development are not sustainable in the long run.

Common attributes of sustainable communities frequently identified in the literature, in professional discussions, and in practice include the following: compact, higher-density development, and the more efficient use of land and space; the "greening" of communities with greater emphasis on trees, parks, and open space; an emphasis on redevelopment of underutilized urban areas and on infill development; greater emphasis on public transit, and creating mixed-use environments which are more amenable to walking and less dependent on autos; and energy and resource conservation and low pollution, among other qualities. Increasingly, the resilience of a community to natural disasters is being added to this list of central qualities, as discussed in detail below.

Examples of sustainability initiatives at local and regional levels are increasingly common, with cities like Seattle and Chattanooga organizing their planning and redevelopment efforts around sustainability. The Habitat II meeting in Istanbul in 1996 had as a major theme sustainable cities, and the recent report of the President's Council on Sustainable Development (1996, Chapter 4), Sustainable America, gives considerable attention to the importance of sustainability at a community level.

In addition, however, a number of states also have undertaken studies, appointed commissions, or convened conferences aimed at taking stock of the sustainability of land use and development patterns (including, for example, Florida, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania). In Minnesota, the result was a report (Minnesota Environmental Quality Board, 1995) which identifies weaknesses and ways in which development is not occurring in a sustainable way, and a set of principles, goals, and guidelines for how local sustainability can be advanced.

There are strong reasons to believe that current growth and development patterns are not sustainable in the long-term. Contemporary patterns of land use do not appear to acknowledge the fundamental fact that land, air, water, and biological diversity are finite. Land use patterns are extremely wasteful, economically expensive, and ecologically damaging. There is also reason to question the social sustainability, livability, and quality of life of the communities being created. (For telling critiques of American patterns of land development, see Calthorpe, 1993; Kunster, 1993; and Langdon, 1994.)

SUSTAINABILITY AND NATURAL HAZARDS

Exposure and vulnerability to natural hazards is an important dimension of the sustainability of cities and communities. Natural disasters dramatically illustrate the ways in which contemporary development is not sustainable in the long run. The unprecedented levels of property damages experienced in recent years, discussed in Chapters 1 and 2, are the clearest indication of the unsustainability of human settlements.

There has been considerable acknowledgment in recent years that sustainability and sustainable development imply efforts to create and maintain communities that avoid or mitigate natural hazards. Within the sustainability literature increasing attention is paid to natural hazards. Agenda 21, the action agenda adopted at the 1992 Rio Summit, gives considerable attention to reducing natural hazards, and clearly includes hazard reduction and avoidance in the definition of sustainable human settlement patterns (United Nations, 1992). Chapter 7 of the report proposes a number of pre-disaster planning and post-disaster reconstruction planning activities including "redirecting inappropriate new development and human settlements to areas not prone to hazards" and supporting efforts at "contingency planning, with participation of affected communities, for post-disaster reconstruction and rehabilitation" (United Nations, 1992, p. 61-62).

The recent report of the President's Council on Sustainable Development gives considerable attention to natural hazards, and includes as a specific action agenda item the identification and elimination of "government subsidies, such as subsidized floodplain insurance and subsidized utilities, that encourage development in areas vulnerable to natural hazards" (1996, p. 99). Increasingly, the literature and the debate about sustainability encompasses natural hazards (e.g., see also Berke, 1995; Geis and Kutzmark, 1995).

Similar connections are being made by the natural hazards community. One of the strongest expressions of the connection between sustainability and natural hazards can be seen in the recent report of the National Science and Technology Council (1996). The need for society to move toward greater sustainability is a major and recurring theme in its report, Natural Disaster Reduction: A Plan for the Future. The report suggests, for instance, that an additional criterion be added to what sustainable development means and requires (in addition to economic growth, environmental protection, and sustainable use of ecological systems): "There is . . . a fourth criterion of equal importance: sustainable development must be resilient with respect to the natural variability of the earth and the solar system" (National Science and Technology Council, 1996, p. 2). This natural variability includes such forces as floods and hurricanes and shows that much economic development is "unacceptably brittle and fragile" (p. 2).

Current patterns of land use have much to do with why development is "brittle." Many of the places experiencing the highest growth rates, and the most sprawling development patterns, are also subject to severe natural hazards. Consider the level of development in southern California, development along the Wasatch front in Utah, development in the Outer Banks of North Carolina or the Florida Keys, or redevelopment of the Oakland hills, as Platt points out in Chapter 2. Community land use patterns are clearly not sustainable if they allow or encourage the exposure of people and property to significant risks from natural hazards, and if alternative settlement patterns are available that would avoid such exposure.

Contemporary land use patterns and practices contribute to placing people and property at risk in both direct and indirect ways. Obviously, human settlement patterns are not sustainable when people and property are placed directly in harm's way (e.g., growth in close proximity to ocean fronts subject to storm surge and shoreline erosion, construction in high-risk landslide areas or wildfire zones, etc.). But breakdowns in

sustainability also occur in more indirect ways, for instance when land use patterns and practices serve to undermine the ability of the natural environment to absorb hazards or generally alter important natural systems. The creation of dramatically greater areas of impervious surface (road surfaces, parking lots, buildings), for instance, can lead to increased downstream flooding. Constructing seawalls, floodwalls, or levees may serve to exacerbate flood problems in other areas or reduce the ability of the larger ecosystem to naturally buffer or absorb these natural forces.

There is another important way in which natural disasters and sustainability are related. Most major natural disasters—whether hurricanes, floods, or earthquakes—present clear opportunities to rebuild in ways that promote greater sustainability. By moving people and property out of higher-risk locations, long-term sustainability of a community can be enhanced (for instance, relocating development out of the floodplain as occurred in a significant way following the 1993 Midwest floods). It is important to recognize also that long-term community sustainability can be enhanced in other ways (non-land use), during recovery and reconstruction. For instance, homes and businesses can be rebuilt so that they are more energy efficient, use renewable sources of energy (e.g., solar), minimize waste (e.g., incorporate new water conservation technologies), and minimize the creation of toxins and other harmful pollutants. Increasingly, rebuilding following disasters must be viewed as an important opportunity to move society in the direction of greater sustainability. Often (and perhaps increasingly) these opportunities will be massive. Consider the case of Hurricane Andrew, where some 28,000 homes in Dade County were destroyed, and some 107,000 homes were damaged. With so much housing to replace, even if small improvements were made in the energy and resource efficiency of the new and rebuilt structures, the potential reduction in associated environmental stresses would be considerable.

William Rees has been advocating the use of the concept of the ecological footprint as a way to conceptualize and understand the implications of consumption and development patterns, and this concept has tremendous application to natural hazards as well (Rees, 1992; Wackernagel and Rees, 1996). The ecological footprint, simply put, is an estimate of the land and water area needed to support consumption and development practices. Included in these calculations is land necessary to produce food and provide housing, transportation, and other consumer goods. Not surprisingly, Rees concludes that the average North American has a very large ecological footprint (each person re-

quires about five hectares), and that North American lifestyles are supported through the appropriation of carrying capacities of other regions and nations. Ecological footprint analysis can be done at a number of levels (from the individual to the national policy level), and might be adapted to take into account natural hazards and disasters. The costs—environmental and economic—for instance, of locating a housing development in the floodplain might be incorporated into an ecological footprint analysis. The displaced flood waters must be mitigated or managed in some way by society; this might take the form of additional acreage of wetlands downstream or flood storage capacity, or might be expressed in terms of the economic damages from future floods. Also, redevelopment following a disaster, by reducing displacement of floodwaters, for example, or by reducing energy and resource consumption, can serve to substantially reduce the ecological footprint. In these ways, hazard mitigation and sustainability are closely and intimately linked.

What this suggests is that there are several ways of understanding the relationship between sustainability and natural hazards. Exposure to natural hazards clearly reduces a community's sustainability. This vulnerability may be reduced (and the community made more sustainable) through a variety of different measures, including but not limited to land use planning and policy (for instance, by strengthening the community's building code). And natural disasters may present significant opportunities to enhance several different aspects or dimensions of local sustainability, including but not limited to reducing exposure to future disasters. While reducing exposure to natural hazards through land use planning and policy is the primary focus of this book, it is important to keep in mind these other relationships between sustainability and hazards; indeed, the holistic nature of a vision of sustainability requires no less.

Increasingly, hazard mitigation and disaster redevelopment efforts are being described under the rubric of sustainability. A number of recent examples can be cited which illustrate the increasing relevancy of sustainability to natural hazards and which show that these concepts are resonating positively with the natural hazard community, and in particular how land use policies and actions can enhance the sustainability of communities. The granddaddy of these efforts took place in Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin, which chose to relocate its business district entirely out of the floodplain of the Kickapoo River, while at the same time achieving a number of other sustainability objectives, including use of solar energy (new businesses were required to obtain at least half of their

Soldier's Grove, Wisconsin, chose to relocate its business district entirely out of the floodplain of the Kickapoo River, while at the same time achieving a number of other sustainability objectives, including use of solar energy. Like other businesses in the town, Turk's grocery is solar heated (DOE).

energy from solar), conducting life-cycle analysis of building materials, siting buildings and landscaping based on site analyses, as well as mixing housing into the downtown (Becker, 1994). Following the disastrous Midwest floods of 1993, efforts to rethink redevelopment patterns were defined and conceived of in terms of promoting more sustainable communities. A group calling itself the Midwest Working Group on Sustainable Redevelopment formed to encourage flood-damaged communities to think about more sustainable patterns of redevelopment and rebuilding. With U.S. Department of Energy funding, a conference was convened to explore these possibilities, bringing together experts on various aspects of sustainability and community leaders from the region. Several flooded communities took up the charge, in particular Valmeyer, Illinois, and Pattonsburg, Missouri. Valmeyer chose to relocate entirely out the Mississippi floodplain and to create, essentially, a new town designed and built at least in part with sustainability in mind. While not entirely successful, it has encouraged energy conservation and use of solar and geothermal energy. The town of Pattonsburg took a similar approach

following the Midwest floods, also choosing to relocate a major portion of the community outside of the floodplain, and again organizing its efforts around the notion of sustainability. The town, in fact, adopted a "Charter of Sustainability" to guide redevelopment, as well as new energy-efficiency and resource-conservation standards, a pedestrian-friendly and solar-oriented new street layout, and a system of constructed wetlands to treat urban run-off, among other features (President's Council on Sustainable Development, 1996, p. 98).

Following the devastating effects of Hurricane Andrew, there were also a number of efforts in south Florida to rethink development patterns more along sustainability principles. Design charettes were conducted, and as a result of one of the more important of these, Habitat for Humanity built an impressive affordable housing project near Homestead. Called "Jordan Commons," the project reflects a new sense among Habitat for Humanity officials that the focus of their efforts should be on creating viable and sustainable neighborhoods, rather than on building individual housing units. The project is unique in its attempt to link safety from future hurricane events (e.g., steel frame structures, which do much better in future events) with a variety of other provisions to support ecological and social sustainability.

As these examples illustrate, some communities are beginning to see reduction of exposure to natural hazards as an essential dimension of their long-term sustainability, and land use planning as an important tool for achieving greater sustainability.

PRINCIPLES OF SUSTAINABILITY/ SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITIES

The broad vision of sustainability which began this chapter was a useful theoretical starting point. For a more detailed vision and more specific guidance regarding the land use policies, programs, and practices described and advocated in this book, an additional set of principles of sustainability or sustainable communities may be useful. Again, I use the term sustainable communities (or community sustainability, sustainable community development, sustainable cities) because it orients us toward the local and regional levels, and toward contemplating more sustainable human settlement patterns. The coupling of communities with sustainability is also important in that it captures the concern about people and overcomes a common criticism that the vision of sustainability is overly or exclusively environmental.

Sustainable Communities Minimize Exposure of People and Property to Natural Disasters; Sustainable Communities are Disaster-Resilient Communities

Any vision or theory of sustainability must prominently include consideration of the long-term safety and survivability of communities and their citizens. Protection from, and avoidance of, natural disasters is an important element of sustainability, and I believe they should receive greater emphasis. A sustainable community, then, is clearly one that seeks to avoid exposure of people and property to natural phenomena like hurricanes, floods, and earthquakes. Communities are sustainable when they can survive and prosper in the face of major natural events. Avoidance is the preferable approach, but sustainable communities recognize that some exposure is inevitable (for example, wind forces from hurricanes and coastal storms, which in Florida and other coastal states are unavoidable) and can lead to achieving other important community goals. Minimum building codes and construction standards, for instance, are important components of a sustainable community, as are minimum facilities for sheltering, and programs, policies, and actions for evacuation of residents from high-risk areas.

As the preceding chapters of this book illustrate, there are many different land use tools and techniques promoting avoidance and reducing exposure to natural hazards. They range from land acquisition to land use regulations and to information dissemination. The relocation program undertaken following the 1993 Midwest floods is an example of efforts to avoid disasters, and the actions of communities like Soldiers Grove, Valmeyer, and Pattonsburg, are examples of efforts to create more fundamentally sustainable patterns of human settlements when the long-term is considered.

Sustainability does not, however, necessarily mean that all risk is eliminated; sustainable communities strive to balance risk against other social and economic goals. Some degree of risk from natural disasters may be necessary and acceptable. For instance, a number of coastal communities around the country have heavily developed shorelines, subject to extensive natural hazards, including hurricanes, sea-level rise, and long-term erosion. For some communities, strategic retreat or relocation will not be feasible. And, indeed, their location along the beach or shore has economic and aesthetic desirability. The vision of sustainability for communities such as Charleston, South Carolina, or Ocean City, Maryland, will not mean abandonment of their sites, but sensible policies to

strengthen buildings, facilitate evacuation, and protect and enhance the natural features and qualities of these places (and, for instance, the choice of beach renourishment over structural hardening of the shore). Sustainability also implies an equitable distribution of the costs of these risks and the programs (such as beach renourishment) for mitigating them.

Where communities choose to allow development to occur in areas exposed to natural hazards, and where there are few alternatives (such as in the case of south Florida), this development can occur in ways that support or advance sustainability, and can generally help create more disaster-resistant communities. Considerable attention in recent years has been focused on development that is sensitive to the environment, and clearly the design of buildings and neighborhoods can reduce long-term risk. Among other things, development can avoid particularly hazardous portions of a site (e.g., occurring away from a surface fault line or away from steep-slope areas), can respect and protect the natural conditions and features that reduce risk (e.g., minimizing impervious surfaces and destruction of vegetation), and can restore and re-create the natural functions that may have been diminished or destroyed (e.g., creation of wetlands, natural drainage swales). (For examples of such environmentally sensitive development projects, see Berke and Beatley, 1992b; Brewster, 1995.) Where possible, ecological infrastructure should take the place of traditional engineering solutions. Such approaches, in working with nature rather than against it, can at the same time accomplish the preservation and enhancement of a range of natural values (e.g., protection of wildlife habitat, creation of significant recreational areas). These projects can often achieve the same results (for example, drainage, flood control) as more conventional engineering solutions, but at significantly lower financial cost.

A sustainable community, then, is a resilient one; it is a community that seeks to understand and live with the physical and environmental forces present at its location.

Sustainable Communities Recognize Fundamental Ecological Limits and Seek to Protect and Enhance the Integrity of Ecosystems

A sustainable community seeks to promote land use and development patterns that acknowledge fundamental ecological limits and operate within the natural carrying capacities of the region. Many of our more serious natural hazards are a direct result of a failure to understand the regional ecological context and to live within it. A sustainable com-

munity acknowledges the presence of natural features and processes, such as riverine flooding and natural wildfires, and arranges its land use and settlement patterns so as to sustain rather than interfere with or disrupt them. Riverine systems, for instance, represent areas of biological and ecological importance, and the vision of a sustainable community is one that respects and protects these qualities.

A consistent theme in this book has been the desirability of assuming a regional scale of planning and management. It has been observed in several chapters that the existing system of local governance is fragmented and fractured and does not correspond very well with important natural boundaries. Implementing programs through local government jurisdictions tends to be a fragmented process that works against consideration of the cumulative effects of land use changes over space and time. (How will we know how much, if any, alteration of the watershed can be tolerated before the impacts are unacceptable?) The vision of sustainability, however, strongly supports the need for planning and management at broader regional, bioregional, and ecosystemic levels. Effective strategies for protecting the integrity of the environment, and for addressing a host of important environmental conservation issues (e.g., wetlands protection and restoration, non-point water pollution control, habitat and open space protection) all require broader regional or ecosystem-level strategies.

A sustainability approach to natural hazards understands that frequently the most effective way to reduce vulnerability of people and property is to preserve a healthy, well-functioning ecosystem. There have been considerable experience and consensus over the years concerning the mitigative benefits of the natural environment, for instance the benefits of wetlands, beaches, and dunes (e.g., see Phillippi, 1994-95; Thieler and Bush, 1991). One dramatic case is the decision by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to acquire and protect 8,500 acres of natural wetlands in the Charles River (Massachusetts) watershed as an alternative to constructing new flood control works. This strategy of protecting the natural functioning of the environment has proven effective and costs an estimated one-tenth of the cost of flood control works (National Park Service, 1991).

The benefits of a regional, ecosystem approach are perhaps most evident when considering riverine flooding and management of riverine systems. Several earlier chapters have pointed out the destructive effects of upstream actions, such as the building of levees and floodwalls, and the cumulative impacts of discrete land use actions (e.g., the filling of

wetlands). The recent report of the Interagency Floodplain Management Review Committee (the ''Galloway Report") strongly recommends a move toward more of an ecosystem approach, which acknowledges and protects the natural qualities and functions of the river system (Interagency Floodplain Management Review Committee, 1994).

Successful examples of regional and ecosystem-level management are few. Collaborative management efforts such as the Chesapeake Bay program (and other examples of the Natural Estuaries Program) have had modest, though promising, results (see Chapter 3 for a discussion of this approach). Watershed councils in the northwest and bioregional commissions in California are other promising examples. Effective regional and planning governance is rare in the United States, though the accomplishments of the Portland Metropolitan Service District suggest it is possible. There "Metro" is coordinating an ambitious effort to develop a regional plan for the year 2040. A regional "growth vision" concept has already been adopted, embracing the need to promote compact growth, focus development and redevelopment into existing centers, and protect open space and the natural environment. A more detailed framework plan is being developed to coordinate and guide regional investments and the individual local plans in the region. While Portland's Metro has unique and extensive regional planning powers, it illustrates the importance of planning at this scale for achieving a variety of objectives related to sustainability, including protection of open space and biodiversity, compact development, and a settlement pattern and landscape resilient to natural hazards. As difficult as it may be to bring about, the vision of sustainability is one that assumes, at least in part, an ecosystemic or bioregional management perspective.

Sustainable Communities Promote a Closer Connection With, and Understanding of, the Natural Environment

The vision of sustainability also includes a fuller, deeper understanding of, and connection with, the natural environment. Indeed, there is considerable and increasing evidence of the importance of exposure to nature, especially during childhood, even in very urban environments (e.g., see Kellert, 1996; Nabhan and Trimble, 1994). Sustainable land use patterns attach greater importance to these connections and strive to promote and reinforce them. Floodplains and riparian areas, for instance, begin to be seen as important avenues for people to experience nature and the natural environment. Coastal land use that seeks to di-

rect development back from and away from natural beaches and dune systems acknowledges that doing so preserves these areas for important recreational uses, and can provide opportunities for individuals to experience the coastal natural environment.

Areas subject to natural hazards, whether riverine flooding, wildfires, or seismic mass movement, are seen then as important elements of a land use mosaic that values natural lands as an important part of the human settlement pattern. Even exposure to micro-habitats (i.e., small natural areas) is beneficial, whether it is the nearby butte, the creek behind a row of houses, or the natural space set aside to avoid a surface fault zone. There are increasing examples of environmentally sensitive development projects that, through clustering and creative site design, have been able to set aside such natural areas.

There has been much concern in recent years that our communities and regions do not advance or inspire a sense of place, and that people do not have a sense of being rooted in a particular place. Much of the support for bioregionalism is based on developing a greater sense of connection with and commitment to place (e.g., see Sale, 1991). Acknowledging and understanding natural hazards is primary in developing a sense of place. Indeed, the natural forces that shape a place—storms along the coast, movement of the earth, landform, and topography—should be viewed within a sustainability framework as defining elements of a place or region, as fundamental attributes of where we live. Children and adults learn about them, appreciate them, and integrate them into their fundamental understanding of where they live, of their home.

Sustainable Communities Seek to Reduce the Consumption of Land and Resources in Fundamental Ways

At the heart of the idea of sustainability is recognition of limits, and of the need to curtail human consumption of land and resources. Without such collective restraint, we will be unable to achieve sustainable communities. The goal of minimizing environmental impacts is certainly not a new one in planning and the other professions with an interest in land. Ian McHarg (1969) made the passionate plea for "designing with nature" more than a quarter of a century ago. Substantial progress has been made in promoting environmental planning and management. Yet a sustainable community is one that does not accept business as usual. It is more than saving a few acres of the habitat of an endangered species,

or requiring a few "best management practices" to abate non-point-source pollution. Rather, it represents a basic shift in philosophy. Instead of sporadic, incremental adjustments to meet environmental ends, sustainable communities seek to use and consume only the amount of land that is absolutely necessary, and to cause environmental destruction only as a last resort and where no reasonable alternatives exist. The practical implications of this principle for land use are numerous: in essence, land is consumed sparingly, environmentally sensitive land (wetlands, habitat, mountainous areas, coastal shorelines) is placed off-limits, and development and land use practices reduce the consumption of resources at every stage.

This philosophical shift has important implications for the physical form future communities assume. Reducing the inefficient, wasteful, and destructive practice of low-density sprawl becomes a priority in a sustainable community. Cities and towns become more compact and contained, and rely more heavily on infill, redevelopment, and reurbanization within areas already committed to urban development. Compact development patterns can in turn be very complementary to the reduction of natural hazards. Curtailing scattered development and sprawl often means curtailing development in the most dangerous and hazardous locations, as we have seen (e.g., areas prone to wildfires or coastal flooding). It may also allow for more efficient public investments and responses to protect against these hazards (e.g., reducing need for wildfire-fighting capability in certain areas).

Sometimes, however, the goals of compact growth and avoidance of hazardous locations conflict with each other. In some situations containment of growth may actually direct development onto more hazardous sites (e.g., urban floodplains or steep-slope locations previously avoided). Both goals must be considered and high-risk sites within the city avoided—indeed, such areas are important in providing parks and green spaces for urban residents. Recent "reurbanization" efforts by the city of Toronto illustrate how this can occur. Areas of the city have been identified where reurbanization could occur, but the urban floodplain has been designated off-limits. It is possible through such a plan to encourage infill and intensification (reducing the consumption of land at the urban periphery) while at the same time discouraging development of hazardous locations within the city.

As the recent examples of Soldiers Grove, Pattonsburg, and Jordan Commons illustrate, it is also possible to minimize the overall ecological footprint of development at the same time that we achieve safer commu-

nities. These examples show that sustainable communities seek to use renewable resources (e.g., solar energy) and limit the consumption of energy and water, at least at the scale of small villages.

Sustainable Communities Recognize the Interconnectedness of Social, Economic, and Environmental Goals

A sustainable community is also one that seeks to integrate social and environmental goals. It is not simply the protection of the natural environment that is important, but the consideration of a broader set of social and economic goals. People are important in this vision, as is the quality of the resulting communities and development. Indeed, the vision of sustainable communities holds that we must consider and promote settlement patterns and policies that accomplish both social and environmental goals.

A number of important social and economic goals are included in the vision of sustainability. These include the availability of affordable housing, transportation, and mobility; access to basic public services and facilities; access to recreation; creation of livable and aesthetically attractive places; and access to jobs, income, and economic activity. The last, economic vitality, is a particularly important component of a sustainable community. To sustain itself in the long run, a community requires the development of a sustainable economic base. In the context of natural hazards, a sustainable economy is one that is resilient and robust in the face of natural events like floods and earthquakes. Keeping businesses and economic infrastructure out of and away from high-risk areas, and areas where natural events cause repeated economic disruption, is one way to go about promoting a more sustainable local economy (along with other mitigation measures such as building codes and construction standards).

The high degree of dependence of many communities on federal and state disaster assistance also raises questions about how sustainable they are. Indeed, the vision of sustainablity in part embodies a spirit of responsibility and self-sufficiency, and heavy reliance on outside resources appears inconsistent with this. Communities must be better prepared to cope with the financial implications of disaster events and should be expected to utilize more of their own resources, at least in all but the most catastrophic of disaster events. Partly this means accepting more responsibility for allowing, or even actively promoting, development in vulnerable places, and striving to reduce this over time; it also means

setting aside resources (financial and otherwise) that will be needed to repair and rebuild the community when a disaster occurs.

A sustainable economy includes activities that are environmentally benign and ecologically restorative, which means avoiding economic and industrial activities that heavily degrade the environment, and that destroy or use up the environmental capital of an area. Recall that at the heart of many of the definitions of sustainability is the notion of maintaining ecological capital. Increasingly it is recognized that heavily extractive industries (e.g., timber, mining, ranching) do not account for as much economic activity and jobs as once thought, and that maintaining and protecting the natural environment may have a much greater positive economic effect [e.g., creating attractive places to live and retire, or places attractive to new industry—what Power (1996) calls the "environmental view of the economy"].

Protecting the ecological capital of a community or region will very often also mean steering development away from high-risk locations and maintaining these areas for their natural qualities, such as coastlines, estuarine shorelines, and areas subject to landslides. In this way, the goals of providing a thriving and healthy economy are inherently interconnected with preserving a healthy environment, and degrading or destroying the latter is not necessary to promote the former. Sustainable communities, then, view the environment, social life, and economy as interconnected. Sustainability is not simply about protecting the natural environment.

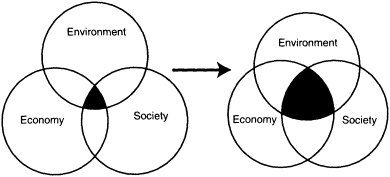

Understanding the connections between these different realms is central to the vision of sustainable communities. As Figure 8-1 illustrates, this is the intersection where much of our energy should be focused, and indeed a central goal of sustainability is to increase the overlap between economy, environment, and society; to promote programs, policies, and strategies that simultaneously respond to these different realms (see the report issued by the Governor's Commission for a Sustainable South Florida, as contained in FAU/FIU, 1996). These interconnections have clear relevance to natural hazards. Protecting the integrity and health of ecosystems can at the same time reduce exposure to natural hazards (e.g., by leaving the natural floodplain untouched), enhance the quality of life in the community (by protecting open space, and creating opportunities to enjoy rivers and wildlife), and strengthen the economy and economic base of the community (e.g., by reducing damage and dislocation to businesses).

FIGURE 8-1 Sustainable communities work to maximize the overlap between environment, economy, and society.

Source: Report of the Governor's Commission for a Sustainable South Florida, as contained in FAU/FIU, 1996.

Sustainable Communities Promote Integrative and Holistic Strategies

Sustainable communities seek to address a number of goals simultaneously and promote strategies and policies that are integrative and holistic. Sustainable communities look for ways of combining policies, programs, and design solutions that bring about multiple objectives. No longer is it possible or desirable, for instance, to view housing policy in isolation from environmental policy or transportation policy or land use policy. This characteristic has clear implications for reducing exposure to natural hazards. Flooding problems in a community may be effectively addressed by certain land use strategies that accomplish other goals at the same time. Certainly protection of wetlands serves to both mitigate flood hazards and to protect important economic and biological resources. Promoting a compact urban form, and urban infill and reuse, can provide more affordable housing at the same time that it prevents or reduces consumption of land at the urban periphery, possibly in turn reducing exposure to natural hazards.

There are many other ways in which natural hazard reduction and other goals can be integrated in the service of community sustainability. The Jordan Commons project mentioned earlier is an example of an effort to simultaneously create a socially cohesive neighborhood, provide safer hurricane-resistant homes, and promote environmental sustainability in the form of more energy- and resource-efficient structures. A

number of communities have sought to establish a system of greenways formed in large part from creek beds and floodplains. (These communities include Raleigh and Charlotte, North Carolina; Boulder and Littleton, Colorado; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Tulsa, Oklahoma; and Scottsdale and Tucson, Arizona. See Little, 1995; National Park Service, 1991; Smith and Hellmund, 1993.) Such greenways protect important ecological features, create areas of special recreational and aesthetic value, and at the same time reduce exposure of people and property to flooding.

Watershed protection efforts, such as the Austin (Texas) Comprehensive Watersheds ordinance, serve simultaneously to protect water quality, reduce flooding, protect important habitat, and set aside valuable open space. Multi-objective river basin planning, which has occurred successfully along several major rivers, is a further example of this integration. Successful efforts to integrate flood-loss reduction, ecological restoration, recreation, and other goals has occurred, for instance, along the Charles River (Massachusetts), the South Platte River (Colorado), the Chattahoochee River (Georgia), and the Kickapoo River (Wisconsin), among others (see National Park Service, 1991). The buyout program following the 1993 Midwest floods has offered similar opportunities to accomplish multiple objectives, and the National Park Service has helped several communities to develop green-space plans for floodplain areas where buyouts and relocation efforts have taken place (Hanson and Lemanski, 1995).

Sustainable Communities Require a New Ethical Posture

Promoting sustainable communities is ultimately about embracing a new ethical posture. There are several important dimensions to this new ethic. Most definitions of sustainability, as we saw earlier, contain at their core a moral reorientation toward the future. The ethic of sustainability explicitly argues for an expansion of the "moral community"—that is, the people or things to which we have a moral duty and whose interests we must consider when making land use and environmental decisions. Under a vision of sustainability it is no longer morally permissible to assume a narrow or traditional short-term time frame in decision making. (This perspective is elaborated on in Beatley, 1994.) The idea of a moral community has significant implications for exposure to natural hazards. Communities have an obligation to consider the impacts of land use policies on future residents and future generations. While a

gradual increase in impervious surfaces may have little discernible effect in the short term, what will be the impact on flooding and run-off over a much longer time span? While the construction of a single house on a barrier island may have little effect in the short run, what longer-term development patterns are put into motion by such an approach, and what are the implications for the safety of future residents?

The importance of a longer time frame for mitigation of natural hazards is clear. Much of the current risk and exposure is a result of a past failing to think carefully about the long-term, cumulative effects of individual and community actions—what will be the effect on flooding of continued loss of wetlands, deforestation, and increases in impervious surfaces in the watershed? What will be the effect of allowing incremental development in wildfire-prone areas, or areas of steep slopes? What will be the effect on long-term community risk patterns of building a bridge and causeway system to an undeveloped barrier island? Extending the moral time frame results in greater importance accruing to long-term risk reduction—for example, perhaps imposing a 100- or 200-year coastal setback line, or projecting, say, at least one hundred years into the future the incremental loss of wetlands in a watershed and the likely disastrous results.

The precautionary principle often comes up in discussions about sustainability. It states that uncertainty about the extent and nature of environmental impacts should not prevent actions to protect or restore the environment. From an ethical point of view, this principle suggests that we err on the side of caution and conservatism and refrain from actions that may have serious, long-lasting, and potentially irreversible effects, even though such results may not be certain. Under this principle many anthropogenic environmental impacts that we often accept cavalierly would be questionable or unacceptable, such as causing the extinction of a species and loss of biodiversity generally, destruction of wilderness, allowing the continuing emission of greenhouse gases, or the continued loss of topsoil. The precautionary principle suggests that we refrain from altering the natural flow of rivers, that we refrain from structural alteration and reinforcement of the coastline, that we prohibit the filling of wetlands and the destruction of vegetation that provides important wildlife habitat, and that we discourage the needless replacement of natural land with impervious surfaces. Such a principle reinforces the need to take action to prevent exposure of people and property to natural hazards even where their nature and magnitude are uncertain. It supports the need to adjust human settlement patterns to take into

account the effects of potential sea-level rise even though there remain uncertainties about its rate and areal effects.

Sustainability also involves an expansion of the moral community spatially and geographically. What obligation does a community have to consider the effects of its actions and policies on other communities and populations, in some cases located many miles away? A community considering, for example, whether to permit development in its floodplain must consider that these decisions may displace floodwaters onto other down-river communities. A community's land use, transportation, and energy policies, as a further example, have significant implications for the generation of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. The ethical posture of a sustainable community takes these extra-local impacts into account. Sustainability also expands the moral community to consider the interests of other forms of life (see Beatley, 1994, Chapter 7).

The new ethical posture is also one that clearly emphasizes the importance of community, where citizens and community groups are willing and able to see and pursue a larger public good. Self-interest and self-benefit are moderated out of respect for the needs of the larger public, including future generations. At an individual level, a developer understands that his or her desire to build along a high-risk shoreline must be moderated by the larger community's need to preserve the beauty of this land and to ensure the safety of its residents, present and future. The desire of a landowner to erect a new home in the floodplain is restrained by the realization that such an action may have serious ramifications for others and the broader public.

The ethics of sustainability affect how we perceive private property rights. Platt notes in Chapter 2 that recent takings challenges, and the property rights movement generally, are significant impediments to land use planning and management. The new ethical posture would clarify and reestablish the ethical content of private property ownership and use. Private property has never been inviolable and absolute, but rather is subject to collective regulation and control (Beatley, 1994, Chapter 9). The ethics of sustainability suggest that land use is a privilege, collectively bestowed, not an absolute right. No landowners ought to have the right to build houses in the floodway, for instance, if this serves to displace waters onto other people's property or damages the integrity of the riverine ecosystem. No property owners ought to have the unfettered right to, say, fill the wetlands on their land.

In part, the ethical posture toward the use of land and property implied by sustainability ought to be left to individual property owners to

translate into action. Indeed, it has proven difficult for government to effectively enforce land use and development regulations (e.g., consider the problems enforcing the south Florida building code, which were evident following Hurricane Andrew). Ideally, the vision of sustainability helps to reinforce a more environmentally and socially responsible ethic of private ownership and use of land. Precisely how this more respectful private land ethic could be nurtured is unclear, but it surely is a function of education, good example, and a system of societal signals and incentives that rewards positive behavior and penalizes negative behavior.

Sustainable Communities Seek a Fair and Equitable Distribution of Resources, Opportunities, and Environmental Risks

Sustainability implies a strong concern for social equity. We must always ask the question, Sustainable for whom? Sustainable communities, then, are places that emphasize social diversity and social, ethnic, and cultural inclusiveness. Sustainable communities are concerned about and strive to promote a fair and equitable distribution of community benefits and opportunities, and a fair sharing of costs and risks.

Natural disasters are not always fair and equal in their impacts, and there are important ways in which a sustainable community in its pursuit of safer, less hazardous land use patterns must be cognizant of social equity. Is risk minimized or reduced for some economic or social classes and not others? Must certain groups endure higher levels of risk? For instance, high-risk floodplains tend to be the location of very inexpensive housing, whose occupants, the community's poorest citizens, are the most vulnerable to flooding. This kind of housing pattern, of course, is not sustainable either from a natural hazard reduction or a social equity point of view, and a program to address the problem might consider these two goals at the same time. A sustainable community seeks to minimize such inequities in response to risks.

Public efforts to make a community more sustainable from a natural hazard perspective may sometimes serve to exacerbate social inequities. For instance, there has been concern that efforts to buy out floodplain properties following the 1993 Midwest floods would have the undesirable effect of reducing the overall supply of affordable housing in riverside communities. As a further example, mandatory seismic retrofit ordinances may have the effect of raising rents and displacing residents; those residents with the fewest economic resources may be the hardest hit by efforts to enhance safety.

In a sustainable community, special efforts are essential to ensure that such effects are minimized. Social equity requires that when a community clears out its floodplain, it must ensure that opportunities for affordable housing are made available elsewhere. And, again, the integrative philosophy implicit in a sustainable community will help. Promoting more compact development, infill, and urbanization, and allowing secondary housing units, for example, can have the important effect of enhancing housing affordability (as in the example of Portland, Oregon).

IMPLEMENTING THE VISION

Building sustainable places means building local capacity to systematically think about, plan for, and effectively shape the future. Several steps in the development process can be identified. An initial step is often understanding the impacts and implications of current patterns and practices of development. A number of analytic techniques and methodologies can prove useful, including the ecological footprint analysis mentioned earlier (e.g., Rees, 1992; Wackernagel and Rees, 1995), carrying capacity studies, and build-out analyses, among others.

The development of sustainability indicators is an important step in understanding the extent to which patterns of development and consumption are or are not sustainable in the long run. A number of communities on the leading edge of the sustainable communities movement have successfully developed such indicators (for example, Seattle, Washington; Santa Monica, California; Cambridge, Massachusetts; Jacksonville, Florida; and the Oregon Benchmarks program; see Community Environmental Council, 1995, for a discussion of sustainability indicators). These indicators, however, typically do not include a natural hazard of disaster vulnerability indicator. Several key indicators could specifically gauge the degree of risk and disaster-resilience of the community, and the extent to which this changes over time. (Are the numbers of people and amounts of property in high-hazard zones on the increase? How many individuals are currently living in seismically deficient structures? What are the trends with respect to impervious surfaces in the watershed?) Sustainability indicators also allow a community to understand its exposure to risk relative to other important community goals, and other resources of sustainability (e.g., availability of open spaces and recreation areas).

Because sustainable community planning is fundamentally participa-

tory and community based, it involves efforts to develop a collective future vision—how the community believes it should evolve and grow over time, and what goals and community attributes people think are important. Very often, design charettes or visioning processes are needed to help in this task. (Such processes have been used very effectively in communities such as Chattanooga, Tennessee; for an extensive discussion of these tools and techniques, see Local Government Commission, 1995.)

Portland, Oregon's 2040 process is exemplary in this regard. Portland Metro has gone to great lengths to engage and consult the public in developing its regional vision, using a variety of methods including a mail questionnaire (with an amazing 17,000+ respondents), community meetings, informational videotapes, and newsletters. Out of this process, a conceptual vision for the future of the region has emerged and will serve as the basis for formulating more specific plans and implementation programs.

Geographic information systems, computer simulations, and other technologies are increasingly useful in helping citizens and community leaders imagine the alternatives available (see also the discussion of GIS in Chapter 5). The California Urban Futures model (CUF) is one recent notable example illustrating the power of these models to show the implications of different community visions, as well as the most effective land use policies and actions to bring them about. The model has been used creatively to show what growth patterns would result in the San Francisco Bay Area under different policy and planning assumptions, including a ''business as usual" scenario, a "maximum environmental protection" scenario, and a "compact cities" scenario (see Landis, 1995). This model allows citizens and policymakers to understand the pattern of growth and the consumption of land that would result if current trends are allowed to continue, and if certain sustainable community practices such as growth containment are implemented. The compact cities scenario would result in the development of some 40,000 fewer acres of land than the "business as usual" scenario (a 35 percent reduction in land consumption in the nine-county area, assuming that all new residential density is 18 persons per acre or greater, and that 20 percent of new growth will be accommodated through infill). The power of this technology is that many other "what if" scenarios can be analyzed, depending on the important components of a region's vision. While the "maximum environmental protection" scenario run for the Bay Area included no development on steep slopes or wetlands, it could be ex-

panded, for instance, to more extensively and directly consider natural hazards. What would the regional growth patterns look like if all 100-year floodplains were placed off-limits, as well as high-risk seismic zones (e.g., areas of high liquefaction potential, surface-fault rupture zones, etc.) and other hazardous features and locations? Computer models like the CUF model will be increasingly important in helping to visualize more sustainable places.

A community or region's vision of a sustainable future, including greater resilience to natural forces, should be translated into more concrete "targets" which indicate when and how quickly progress is being made in moving toward sustainability. Hazard reduction targets could be quantitative, and an early draft of the National Mitigation Strategy offers an example of such targets, albeit at the national level. The 1994 draft strategy sets a 25-year goal for mitigation: "By the year 2020, engender a fundamental change in public attitude that demands safer communities in which to live and work, and thereby reduce by at least half, the loss of life, injuries, economic costs (1994 dollars), and destruction of natural and cultural resources that result from the occurrence of natural hazards" (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 1994b, emphasis added). Unfortunately, perhaps, the final version of the strategy dropped this quantitative goal. Each locality and region will need to develop its own specific targets and measures of progress, depending upon its specific vision of sustainability.

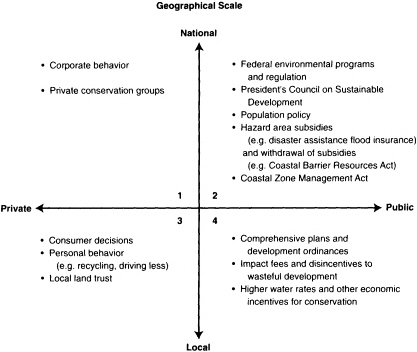

Once goals and targets are identified, implementation becomes the challenge. There are many opportunities for advancing local and regional sustainability, and many different policy levers and initiatives that might be employed. Many of these have been discussed extensively in the previous chapters. Figure 8-2 presents one initial way to understand these opportunities, which exist at both public and private levels. While much of the emphasis of this book is on public sector planning and policy, the private sector holds much potential to influence and promote safer, more sustainable land use patterns. One important private sector level involves the many decisions that individuals engage in—for instance, making decisions about where to live. Individuals have opportunities to promote sustainable land use by buying homes in safer locations, such as outside of floodplains or off the high-erosion beach front, or away from landslide-prone locations. Such actions reflect the principle that individuals have the responsibility to consider issues of sustainability when making a host of personal choices (which often correspond to self-interest). As Paterson strongly argues in Chapter 7, nongovernmental groups

FIGURE 8-2 Opportunities to advance sustainability.

(the "third sector") offer tremendous potential in advancing sustainability. Most of these efforts tend to fall in quadrant three. A host of grassroots environmental groups have a direct interest in hazard mitigation. But environmental groups at the national level, including the National Wildlife Federation and the Coast Alliance, also have been heavily involved in advocating for less destructive development patterns (quadrant 1). Other private sector opportunities include the potentially significant role of groups like the Nature Conservancy, or Habitat for Humanity, or We Shall Rebuild, among many others. These groups can have both direct effects (e.g., buying land, building projects) and more indirect influence in shaping public discourse and dialogue about community sustainability. The sustainability paradigm creates opportunities for different, otherwise disparate, community interests to come together in support of common goals. The emphasis on integrating social and environmental goals means that groups as different as affordable housing advocates, grassroots environmental and open-space conservation

groups (e.g., the Greenbelt Alliance, which Paterson cites), taxpayer groups, and members of the business community, among others, can productively join forces and come together in support of a common agenda. Promoting sustainable communities and land use has the potential not only to keep people and property out of harm's way, but also to provide more affordable housing and better living conditions (e.g., higher-density, more compact development, less reliance on the automobile), to protect important environmental resources and amenities, and to reduce the long-term costs of growth and development, among others. The integrative holistic vision of sustainability, then, creates great opportunities for collaboration and political partnerships.

Most of our discussion in this book focuses on public sector land use policy and planning, activities falling on the right side of Figure 8-2. There are a variety of public policy levers and tools that might be effective in promoting more sustainable places. These include land use plans, regulations (e.g., urban growth boundaries to promote compact cities, zoning restrictions to prevent development in high-risk areas), land acquisition, public investment decisions, and taxation and other fiscal incentives.

The other axis of Figure 8-2 reflects the fact that sustainable community policy can be made and actions can be taken at a number of different jurisdictional scales. At the national level, efforts range from federal environmental laws [e.g., the Endangered Species Act (P.L. 93205, U.S. Code, vol. 16, sec. 1531)] and disaster and hazard reduction programs (e.g., the Stafford Act, the National Flood Insurance Program) to the recent activities and recommendations of the President's Council on Sustainable Development.

The sustainability paradigm offers at least the possibility of overcoming the limitations of the present intergovernmental patchwork, described by May and Deyle in Chapter 3. Indeed, the importance of an ecosystem management approach offers the possibility of federal and state agencies coming together to undertake more collaborative, coordinated approaches and decision making. At the federal level, there has been considerable interest in reorganizing federal actions and policy around ecosystem management and achieving the "vertical linkages" Burby discusses in Chapter 1. A federal interagency task force on ecosystem management recently released its report, strongly endorsing the concept of ecosystem management, emphasizing its many benefits, and recommending that federal agencies facilitate the use of ecosystem management (see Interagency Ecosystem Management Task Force, 1995).

Sustainable communities have perhaps the clearest and most potent application on the bottom end of Figure 8-2—at local and regional development levels. Indeed, this is traditionally where the urban and land use policy functions have resided in the United States, and it is at this level where perhaps the greatest potential exists to promote the vision of sustainability.

It is also true, of course, that policies and programs adopted at one scale have profound impacts on sustainability at other scales. Clearly, national policy in a variety of areas influences the local level, and what can and cannot be done there. Federal transportation, housing, environmental, and economic policy, as well as the federal tax code and other de facto policy instruments, have tremendous impact at the local level. Federal programs such as disaster assistance, flood insurance, tax deductions for second homes and casualty losses, and so on, influence the exposure of local land use patterns to natural hazards.

CONCLUSIONS

Sustainability, then, represents a powerful new theoretical framework through which to understand land use and natural hazards. Extremely high levels of property damage in recent disasters clearly suggest that current patterns and practices of land use and community building are not sustainable in the long run. Creating sustainable places means creating places that are far less vulnerable to natural forces and events,

and that are resilient to these events. A set of principles has been offered for understanding more specifically what sustainability means at local and regional levels. Among other things, the vision of sustainable communities is one where development and patterns of living acknowledge fundamental ecological and resource limits; seek to reduce or minimize the physical footprint; recognize the interconnectedness of social, economic, and environmental goals; seek integrative and holistic strategies; and acknowledge the need for a new ethic and an equitable distribution of risks and resources. The specific issues, opportunities, and leverage points of a sustainable community, and how to build one, will vary from place to place, but ultimately the sustainable community must derive from an open, participative, and democratic process in which citizens and groups contemplate and coalesce around a desirable view of the future of their community.