Exploring Military Exposures and Mental, Behavioral, and Neurologic Health Outcomes Among Post-9/11 Veterans (2025)

Chapter: 2 Background and Military Context

2

Background and Military Context

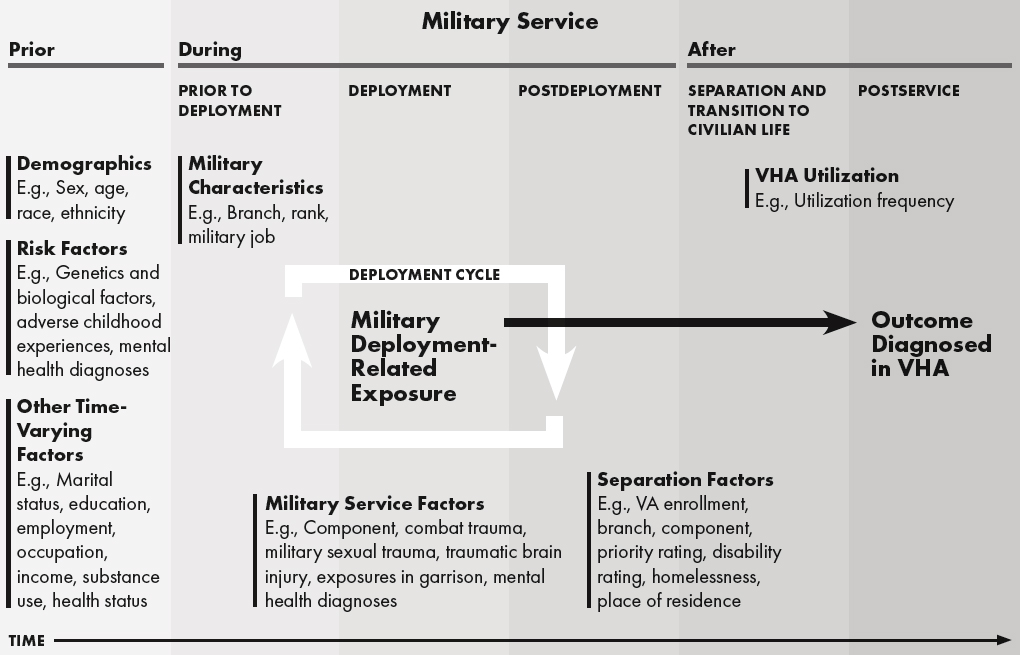

The primary focus of this report is to identify potential associations between toxic military-related occupational and environmental exposures among U.S. service members who deployed to the Southwest Asia Theater of Operations or Afghanistan after September 11, 2001, and the development of mental, behavioral, and neurologic health outcomes and chronic multisymptom illness. Given the evidence that links other possible risk factors to similar outcomes, the committee developed a conceptual framework to apply narrowly to the members of this population. It links demographic factors, premilitary factors, military-related environmental and occupational exposures, other factors during deployment, and postservice experiences to the studied health outcomes. It applies to all exposures and outcomes of interest, because although the committee acknowledges that the pathways by which each exposure affects each outcome are unique, evidence links factors from all phases of the conceptual model to most of the outcomes.

Figure 2-1 illustrates how, across phases of a service member’s life, different factors may contribute to mental, behavioral, and neurologic health outcomes. The framework does not include the comprehensive universe of these potential influences on health and instead focuses on those factors that are related to both the likelihood of military exposure and the outcomes. The framework also does not present all possible relationships: in some instances, these factors may confound a relationship between exposure and outcome; in other instances, they may modify the relationship between environmental exposures and outcomes. The committee focuses on these factors because they can affect its ability to observe the true relationship between a given exposure and outcome in its statistical analyses, presented

NOTE: VA = Department of Veterans Affairs; VHA = Veterans Health Administration.

in Chapters 6–8. To that end, the diagram does not show direct relationships between other factors at different periods (e.g., between demographics and trauma exposure during military service).

The simplified framework is divided into periods that correspond with military careers (broadly, before, during, and after service) and borrows somewhat from the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (Bovin et al., 2023; Vogt et al., 2013). First, relevant factors and experiences are present or occur before joining the military, which can range from genetic profile to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) to mental health diagnoses; this period also includes demographic characteristics, like sex, age, and race and ethnicity. The next stage is before deployment, which includes factors like service branch and occupation and whether someone enlists or enters as an officer. It may also include traumas not associated with deployment, such as those that may occur during training exercises, or those that may or may not be associated with military service, such as sexual trauma, harassment, assault, or non-combat related injuries. The next period (deployment) is particularly relevant to the committee’s task in that this is when a toxic occupational or environmental exposure could occur, possibly in combination with other exposures and factors, like combat trauma, that are relevant to ultimate mental, behavioral, and neurologic health outcomes. It is followed by the postdepolyment phase, which includes factors such as tenure in the military, any subsequent deployments either in Southwest Asia or other parts of the globe, receipt of any health care services, or experiences of any additional stressors not limited to deployment (e.g., family discord, loss of comrades, or military sexual trauma); relevant mental, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes could begin manifesting in this stage. These three subphases make up the deployment cycle, and factors that occur during or after deployment become relevant again as pre-deployment elements to successive deployments. The next phase focuses on separation and transition to civilian life, encompassing factors such as Veterans Health Administration (VHA) enrollment, utilization frequency, Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) priority, and disability ratings. Despite debate about the duration of this phase, a number of factors can influence the experience, including education, employment, place of residence or homelessness, and/or financial stress. (These time-varying factors can also be relevant to military exposures and the relevant health outcomes.) The final phase is the postservice period, when veterans are reintegrated in the civilian setting and health outcomes may be diagnosed in VHA; elements from military service, multiple deployments, and separation factors may emerge or be exacerbated.

This chapter provides context for the relationships between this range of factors and the likelihood of military exposures and/or the mental, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes of interest; it provides examples of these factors rather than comprehensively describing all potential relationships

and influences for all exposures and all outcomes. Chapter 3 describes the environmental and occupational exposures of interest in more detail, and Chapters 6–8 describe the outcomes and the results of the committee’s analysis and literature search on the relationships between exposures and outcomes.

FACTORS BEFORE MILITARY SERVICE

Demographics

Age and Sex

The post-9/11 cohort is younger and includes a higher percentage of women veterans (12–17%) than other veteran cohorts (IOM, 2013; Robinson et al., 2023). Many mental and behavioral health disorders begin in late adolescence and young adulthood (Solmi et al., 2022); it is therefore possible that someone could already be in the early stages of one (e.g., depression or bipolar disorder) before beginning military service or coming into contact with deployment-related occupational or environmental exposures. Additionally, it is challenging to examine outcomes with long latency and late onset (e.g., neurodegenerative outcomes) among this relatively young cohort. However, demographic patterns related to age and sex exist for both deployment-related exposures and the mental, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes of interest. Sometimes, these are relatively straightforward. For example, the onset of schizophrenia typically occurs after age 18 and is later for women than men (NIMH, n.d.). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), however, is more common in men and has an average age of diagnosis of between 60 and 79 years (Al-Chalabi and Hardiman, 2013; Feldman et al., 2022).

In other instances, demographic patterns may be more difficult to untangle. For example, depression and thoughts of suicide (suicidal ideation) are more common among female than male veterans (Hoffmire et al., 2021; Maguen et al., 2012), but suicide rates are higher among men (VA, 2024). This is comparable to patterns observed in nonmilitary/veteran populations and has been referred to as the “gender paradox” of suicide (Canetto and Sakinofsky, 1998). Also similar to civilian studies, female and male post-9/11 veterans have elevated rates of depression and substance misuse, respectively (Maguen et al., 2012; Ramchand et al., 2015).

In at least two studies, women who deployed were more likely to have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after accounting for differences in combat exposure (Luxton et al., 2010; Schell and Marshall, 2008). This also highlights gender-based differences in military exposures. Women have long

served in combat operations, though it was only in 2015 that they were no longer subject to the exclusion policy that restricted them from ground combat arms units or positions (Moore, 2020). As discussed later, certain military jobs may entail a greater likelihood of being exposed to specific environmental exposures, which may explain certain gender differences in the committee’s outcomes.

Race and Ethnicity

Racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes among the general population have been well documented (HHS Task Force on Black and Minority Health, 1985; NASEM, 2017) and thus merit consideration as a factor before military service that may influence the mental, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes of interest, especially considering that post-9/11 veterans are more racially and ethnically diverse than previous cohorts (Barroso, 2019; Holder, 2018; NCVAS, 2018; Robinson et al., 2023). Per 2016 data from the American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample, 20.5% and 33.2% of male and female post-9/11 veterans, respectively, were non-White, non-Hispanic, compared to just 13.3% and 22.2% of all other male and female veterans, respectively. Additionally, 12.0% and 11.8% of post-9/11 male and female veterans, respectively, were Hispanic compared to just 5.7% and 6.4% of all other male and female veterans, respectively (NCVAS, 2018).

The health disparities documented among the general population also appear among veterans. For example, a study of over 400,000 men and women in the Million Veteran Program found racial and ethnic differences in circulatory, musculoskeletal, mental health, infectious disease, kidney, and neurologic conditions, including more reported mental health conditions among Hispanic, Black, and Other men compared to White men and more reported neurologic conditions among Hispanic compared to White men (Ward et al., 2021). Data from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study, a 2019–2020 survey of over 4,000 veterans, also found racial differences in positive screening for PTSD, major depressive disorder, drug use disorder, and suicidal ideation. For example, Hispanic and Black veterans were more likely to screen positive for lifetime PTSD than White veterans (17.8% and 16.7% versus 11.1%, respectively), Hispanic veterans more likely than White veterans with lifetime major depressive disorder (22.0% versus 16.0%), Black veterans more likely with current PTSD and drug use disorder than White veterans (10.1% versus 5.9% and 12.9% versus 8.7%, respectively), and Hispanic veterans more likely with current suicidal ideation than Black veterans (16.2% versus 8.1%) (Merians et al., 2023). A retrospective cohort study of a random sample of veterans who received care at VHA found higher dementia incidence in Black and

Hispanic than White veterans (Kornblith et al., 2022). Data are also suggestive of racial and ethnic differences in related outcomes, such as psychological resilience, alcohol use disorder, and mood and anxiety disorders (Carr et al., 2021; Herbert et al., 2018).

Other Risk Factors

Service members may have risk factors for the mental, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes of interest before joining the military. Most of the outcomes have evidence of genetic contributions, though the magnitude of influence varies. Sibling data from Sweden’s national registry suggest that, among eight disorders examined, genetic influences were most important for autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia (Pettersson et al., 2019).1 A subsequent meta-analysis found heritability estimates of smaller magnitude, though still significant, for many of the outcomes investigated in this report, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, PTSD, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and ADHD (The Brainstorm Consortium, 2018). There appears to be a genetic link for 10–15% of those with ALS (Feldman et al., 2022).

Another type of premilitary stressor that has significant evidence supporting its association with mental, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes is ACEs, which may increase the risk for psychological disorders during and after service. ACEs are defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as “potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood” and include “physical and emotional neglect, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, exposure to domestic violence, mental health problems, family incarceration, separation and substance misuse” (Tzouvara et al., 2023). A meta-analysis provides evidence of a relationship between having experienced four or more ACEs and anxiety, depression, illicit drug use, heavy alcohol use, problematic alcohol use, problematic drug use, and suicide attempts (Hughes et al., 2017). Evidence indicates that individuals who join the military are more likely to have experienced ACEs (Blosnich et al., 2014; Katon et al., 2015), and ACEs are associated with military sexual trauma, especially among female veterans (Doucette et al., 2023). Several studies have documented higher levels of childhood sexual abuse among female veterans compared to their civilian counterparts (McCauley et al., 2015; Scott et al., 2014).

In addition, exposure to environmental toxins during childhood could contribute to development of mental, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes.

___________________

1 The other four disorders studied were alcohol dependence, anorexia nervosa, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. For these, heritability estimates were lower than 0.50, suggesting the more important role of environmental influences.

For example, childhood exposure to lead is associated with lower IQ and greater cognitive decline (Reuben et al., 2017). Service members from rural farming communities may have been exposed to pesticides and fertilizers that may contribute to mental, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes (James and O’Shaughnessy, 2023).

With the advent of the all-volunteer force in 1973 (Lopez, 2023), people were no longer drafted, which ushered in a new era for the military. The characteristics of people who decided to join this all-volunteer force were not always the same as in people from the general population. For example, studies have found that people who are more prone to sensation seeking, impulsive, individuated, and focused on altruistic service are more likely to join the military (Montes and Weatherly, 2014; Woodruff, 2017). These social selection factors may have been particularly present from 2003 to 2008, when many soldiers were granted enlistment waivers for medical concerns, misconduct (e.g., felonies), or positive alcohol/drug tests (Gallaway et al., 2013; Malone, 2014). People may have joined the military for economic reasons, such as having a steady job, or patriotic reasons, such as many doing so after 9/11 out of a desires for national service and a sense of purpose (Carter et al., 2017; Matthieu et al., 2021). People who join the military are more likely to have family who served, and some have even theorized a heritability factor (Beaver et al., 2015; Miles and Haider-Markel, 2019). These intergenerational impacts of war are worth noting because of the high rates of psychiatric disorders among veterans of previous eras, such as the Vietnam War, Korean War, and World War II (Forrest et al., 2018; Ikin et al., 2007; Solomon et al., 2022). Children growing up in military households face unique stressors (e.g., frequent relocations) that may explain elevated rates of behavior problems and/or mental health symptoms in some studies, though this finding is inconsistent (Cramm et al., 2019); these studies highlight the potential intergenerational consequences of war. These preexisting and premilitary factors are important to consider in studying who joins and how they are exposed to toxicants and their potential effects on their mental, behavioral, and neurologic health.

FACTORS DURING MILITARY SERVICE

Factors Before Deployment

The discussion of factors during military service distinguishes between factors prior to deployment and during deployment. This is done for descriptive purposes only and, in fact, most of the factors prior to deployment are relevant risk factors that can be experienced during deployments as well. Similarly, many deployment-related exposures (e.g., repetitive blast exposure) can be experienced when service members are not deployed (i.e., during training).

Military Characteristics

People join a component (Active, Reserve, including National Guard), join specific service branches (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, Space Force), enlist or are commissioned as officers, and choose or are assigned a Department of Defense (DoD) occupation code based on test scores and other factors. While some DoD occupation codes may imply a direct relationship between deployment and the potential for exposures (e.g., infantry), others do not have such an obvious direct line (e.g., medic). DoD occupation codes may only correlate with, not predict, the risk of exposure to environmental toxicants. Other factors, such as type of military action, unit, environmental conditions, and deployment location, also influence exposure.

Trauma Exposures

Service members may experience significant traumas before deploying and being exposed to combat-related traumas (discussed later). Injuries, including traumatic brain injury (TBI), may be a proxy for some of these traumas. While the risk of TBI is significantly greater in deployed than nondeployed environments (Jannace et al., 2025), the latter account for 80–85% of TBIs (though TBIs later diagnosed in nondeployed settings may have been caused during deployments) (Cameron et al., 2012; Helmick et al., 2015). Over half of deployment-related TBIs are caused by a bullet or blast; in nondeployed environments, TBIs result from motor vehicle crashes, military training, sports or physical training, or falls (Jannace et al., 2025).

Another type of trauma is hazing. Service members were asked about 10 potential hazing incidents in the past year in the 2017 Workplace and Equal Opportunity Survey of Active Duty Members; 7.0% reported being “hurtfully insulted” and 4.6% that someone “tried to humiliate” them. Other reported behaviors included having property taken or damaged (2.9%); being deprived of food, water, or sleep (2.2%); being threatened or deliberately caused physical pain (1.9%); being pressured to do something illegal or dangerous (1.3%); having their private body parts touched or being made to touch others’, without a medical purpose, when they knew this contact was unwanted (1.1%); and being pressured to consume harmful amounts of alcohol, water, or other substances (1.0%) (OPA, 2018).

Military sexual assaults are another form of trauma possible in both nondeployed and deployed settings. A meta-analysis of 69 studies estimated that among both service members and veterans, 3.9% of men and 38.4% of women report having had experienced either sexual harassment or assault (Wilson, 2018). In 2023, 6.8% and 1.3% of active-duty women and men, respectively, reported unwanted sexual contact in the past year

(DoD SAPRO, 2024). A good share of these assaults may be considered “hazing”: in 2018, 21% of women and 38% of men who experienced at least one sexual assault described it as hazing and/or bullying (OPA, 2019). Service members who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual face an increased risk of sexual assault (Morral and Schell, 2021). A recent review provides evidence that military sexual trauma is independently associated with symptoms of PTSD, depressive symptoms, and suicidality (Yancey et al., 2024).

Environmental and Occupational Exposures in Garrison

Although this report focuses on military exposures incurred during deployments to the Southwest Asia Theater of Operations or Afghanistan after September 11, 2001, people may be uniquely exposed to such toxicants during military service. Between 1953 and 1985, the drinking water at U.S. Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, contained industrial solvents, including trichloroethylene, which likely contributed to certain forms of cancers (Bove et al., 2024). Exposure to lead in military-provided housing is also possible (APHC, n.d.); although the service branches have monitoring protocols, at least one study of Army housing showed deficiencies in the implementation of the program (Winkie, 2023).

Mental Health and Behavioral Factors

Many of the committee’s outcomes can be disqualifying for enlistment, appointment, or induction into and retention in military service (DoD, 2018, 2020). However, among active-duty service members, including those who have and have not deployed, particularly high rates of adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, depressive disorder, and alcohol-related disorders have been diagnosed and documented, with an estimated overall incidence rate of 8,141 per 100,000 person-years from 2016 to 2021 (Health.mil, 2024b). An anonymous survey study of Army and Marine combat infantry units before and 3–4 months after deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan in 2003 found the number of those screening positive for major depression, generalized anxiety, or PTSD significantly higher after duty to Iraq (15.6–17.1%) than Afghanistan (11.2%) or before deployment to Iraq (9.3%) (Hoge et al., 2004). Rates of mental health disorders among deployed U.S. Army personnel rose between 2008 and 2013, with rates peaking between 2010 and 2012, before gradually declining (Paxton Willing et al., 2022).

Harmful substance use often co-occurs with mental health conditions, potentially contributing to their onset or exacerbating the severity of symptoms. One in 10 veterans has been diagnosed with a substance use disorder (SUD), a slightly higher prevalence than the general population (NIDA,

2019). Some risky substance use begins while in the military. Deployment is associated with smoking initiation, unhealthy drinking, drug use, and other health risk behaviors. Illicit drug use among active-duty personnel is relatively low and monitored regularly with screening protocols. However, they may have higher use of certain prescribed or illicit stimulants, which may be related to military performance or premilitary factors, such as ADHD (Kennedy et al., 2015). Moreover, cigarette smoking used to be common among military personnel (Lopez et al., 2018), and at least one study found that they smoked more while approaching separation from the military and smoking prevalence was higher in veterans than military personnel (Nieh et al., 2021); smoking tobacco and vaping can negatively affect mental health conditions like anxiety, depression, and schizophrenia (Taylor and Munafò, 2019; Wu et al., 2023). Heavy alcohol use (e.g., binge drinking) is elevated among service members in the active and reserve components and is associated with subsequent alcohol use disorder diagnoses—among veterans who consumed alcohol, approximately 9% meet criteria for alcohol use disorder (Adams et al., 2019; Davis et al., 2025; Meadows et al., 2021a, 2021b).

Many other behaviors may also influence whether veterans or service members develop some of the committee’s conditions of interest. These range from diet (Bremner et al., 2020) and exercise (Caponnetto et al., 2021) to energy drink consumption (De Sanctis et al., 2017) and social media use (Valkenburg et al., 2022). Data from the 2018 DoD Health Risk Behavior Survey indicate that DoD is monitoring these behaviors among service members and that many of those in both the active and reserve components engage in behaviors that may put them at risk (e.g., 15.1% of the active component and 19.0% of the reserve component are classified as obese [Meadows et al., 2021a,b]).

Pain and Prescribed Opiates

Pain is prevalent among service members and veterans: approximately 29% of those in the active component and 21% of those in the reserve component report bodily pain and nearly one-third of all veterans over age 20 report chronic pain (CDC, 2020; Meadows et al., 2021a,b). To help manage this pain, health care providers may prescribe opiates: in 2017, approximately one in four members of the active component had a filled opioid prescription and among veteran patients in VHA, prescribing increased from 9% in 2004 to 33% in 2012, declining thereafter (NASEM, 2025; Peters et al., 2019). Although opiates can help address pain, some who use them may develop dependency on them, and overuse can lead to overdose or contribute to mental health conditions and suicide risk (NASEM, 2025).

Deployment Factors

Combat Trauma

Across studies, combat exposures have been among the strongest predictors of many of the committee’s conditions (see, e.g., Bryan et al., 2015; Ramchand et al., 2010, 2015; Yancey et al., 2024). A range of events constitute such traumas—a categorization scheme was developed by King and colleagues (1995) and adapted by Vogt and colleagues (2013). As reviewed by Ramchand and colleagues (2011), “traditional combat events” include “being injured or wounded in combat; killing, injuring, or wounding someone else; and handling or smelling dead and decomposing bodies.” Among those deployed to the Southwest Asia Theater of Operations or Afghanistan after September 11, 2001, depending on survey population and timing, estimates can be as high as 75% experiencing incoming artillery, rocket, or mortar fire. During this time, it became apparent that for those who deployed, blast injuries represented a significant threat (RAND, 2008). Initially, the focus was on blast injuries resulting from improvised explosive devices, but recent attention has been on low-level blast exposures, specifically repetitive neurologic stresses from flying aircraft (Phillips, 2024c), operating speedboats (Phillips, 2024a), or repeatedly firing weapons like mortars (Phillips, 2024b). This is emerging literature, and such repetitive stresses may be associated with the development of mental health or neurological symptoms (Carr et al., 2020).

Another category of exposures is atrocities or episodes of extraordinarily abusive violence and may include witnessing brutality toward detainees or prisoners, reported by 5% of previously deployed personnel in one study (Schell and Marshall, 2008); hitting or kicking a noncombatant when it was not necessary (4–7%); or modifying or ignoring Rules of Engagement (5–9%) (SOG MNF–I and SOG MEDCOM, 2006). Subjective or perceived threats are events that individuals perceive as threatening: as many as 50% of Army soldiers who served in Iraq felt in danger of being killed (Hoge et al., 2006; Milliken et al., 2007).

Environmental Features

The focus of this investigation is toxic military-related occupational and environmental exposures. These are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3, and may be considered as part of a category of deployment-related exposures broadly referred to as part of a “general milieu of a harsh or malevolent environment” (King et al., 1995)—common irritations or annoyances. In addition to a lack of personal space and privacy (SOG MNF–I and SOG MEDCOM, 2006), diarrhea, respiratory complaints, and skin irritation and infection were commonly reported by deployed service

members, revealing concerns about food quality, air quality, and flies or insects (Sanders et al., 2005; Vickery et al., 2008). Physical and mental strains of the harsh environment can have far-reaching impacts: those who have experienced trauma, injury, or hospitalization during combat are at risk for increased drinking or drug use, and veterans with SUD are three to four times more likely to receive a PTSD or depression diagnosis (Teeters et al., 2017).

Social and Psychological Stressors

In general, service members face various forms of psychological stress while deployed as they encounter new environments, hostile combat situations, and social disconnection from family and friends. In modern warfare, psychological and logistical challenges also arise from being embedded within local foreign military forces fighting enemies also embedded in local communities (Caforio, 2014; Hobfoll et al., 1991). This psychological stress can manifest emotionally or somatically. Some soldiers do seek mental health services, and most of the data on psychological stress are limited to those who have sought treatment. One 2018 cross-sectional study reported that about 39% of service members who used mental health services had severe unspecified psychological distress (Cordes et al., 2025), which may affect their sleep and productivity (Hourani et al., 2006; Orasanu and Backer, 2013).

Service members in the relevant population who experienced stress may have impaired sleep (or deficiencies therein), which may bidirectionally contribute to mental, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes. In one study, only 37.4% of service members received the recommended amount of sleep (7 or more hours per night), and 31.4% received 5 or fewer hours per night. In addition, almost half met criteria for clinically significant sleep problems. However, it is not clear whether sleep problems are worse before, during, or after deployment. These were associated with both a probable diagnosis of depression and PTSD in this sample (Troxel et al., 2015), with evidence from multiple studies describing an inverse relationship between sleep quality and many mental, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes (Good et al., 2020).

Postdeployment

The postdeployment period can be stressful for the returning service member and their family. This is when they move from a typically hyper-intense setting with its own norms of behavior to the accepted behaviors in civilian society and in the family. As noted, it can lead to separation from the military and transition to civilian life or become relevant as a

pre-deployment period; the length and number of deployments among post-9/11 veterans range across components and service branches (IOM, 2013). Factors and experiences before and during deployment, such as combat and other traumas, deployment-related environmental or occupational exposures, and mental or neurologic health diagnoses, are therefore important in this phase as well and may be repeated or exacerbated in additional deployments. For example, a population-based, cross-sectional study of U.S. Army and National Guard service members using anonymous surveys 3 and 12 months after deployment found that the prevalence rates of PTSD or depression with serious functional impairment were between 8.5–14.0%, with those reporting some level of impairment between 23.2–31.1%. Alcohol misuse or aggressive behavior comorbidity was present in about half of the cases. Rates remained stable for the active component soldiers but increased from the 3- to 12-month time point for the National Guard, illustrating the persistent effects of service in a combat environment that influence postdeployment care and have implications for redeployment (Thomas et al., 2010). Postdeployment risk also varies by many of the characteristics previously described; for example, in a study of Army soldiers, suicide risk was elevated among junior enlisted soldiers relative to senior enlisted or officers (Adams et al., 2022). Resilience can mediate the effect of postdeployment stressors on PTSD symptoms in some groups of veterans (Wooten, 2012).

In general, active-duty service members deploy with, and return to, members of their assigned unit. They are also generally granted some form of leave to spend with their family. The duration varies by type of unit, policy, and command discretion. Family members may or may not have remained at this location during the deployment period. Uniformed members return to their units and continue in their typical job duties. Active-duty service members are seen within the Military Health System for any physical or mental health issue. They generally continue in their career until their contract ends and they decide to leave or retire from service. Some receive a medical disability determination and may be medically discharged (Health.mil, 2025). Reserve component members, including those in the National Guard, are often moved out of their unit of assignment and serve in a deployed area temporarily, after which they return to part-time duty status and, in many cases, are returned to their home of record. The vast majority of those in the reserve component have a home, family, and job to return to. Those in the reserve component have 6 months of the Transitional Assistance Management Program (TRICARE, 2024), which provides health coverage as they go back to their civilian health insurance. If they were on active-duty orders for 180 days or more, they are deemed to be veterans with certain rights and privileges, including seeking health care through VHA.

This transition can be difficult, as family members must readjust to former roles as the service member returns home and adapts from ways of being “normal” in an abnormal deployment setting to being “normal” in their home station life (Health.mil, 2024a). For example, the RAND Deployment Life Study found service members and spouses became less satisfied with their marriages across the deployment cycle, but more frequent communication during deployment was associated with spouses’ greater marital satisfaction postdeployment (RAND, 2016). Service members also reported higher parenting satisfaction and better family environment during deployment, while spouses’ parenting satisfaction declined, though additional preparation before deployment and more frequent communication during it reversed this pattern. Negative psychological outcomes of deployment, like trauma and stress, were associated with negative family outcomes postdeployment; deployment trauma was associated with increased depression, anxiety, and PTSD among service members, and spouses had similar symptoms and binge drinking when the soldier was injured during deployment. Psychological symptoms were increased in those who separated or retired from the military in the study period.

FACTORS DURING AND AFTER SEPARATION FROM MILITARY SERVICE

Transition to Civilian Life and Postservice

Transition out of the military is a long process—“conditions for postservice success are set well before the uniform comes off” (Ramchand et al., 2023). Topics discussed earlier in this chapter, such as military occupation, exposure to combat, other traumas, and ease of finding postmilitary employment, can affect the experience. Nonetheless, transition is an important process that has implications for not only the development of mental, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes but also whether, when, and where veterans may access treatment to help with these.

Within this phase the cumulative experiences when in uniform can be considered. For those who served in Southwest Asia or Afghanistan after September 11, 2001, the number of deployments has often been hypothesized as a factor that may have contributed to many of the outcomes under investigation. Studies have shown an association between multiple deployments and PTSD (Ramchand et al., 2015), but some have showed the inverse (Luxton et al., 2010; Wilmoth et al., 2015) or a lack of an association between number of deployments and suicide (e.g., LeardMann et al., 2013), suggesting a possible “healthy warrior” effect (Haley, 1998).

Cumulative experiences, whether in the military or not, may also influence the development of ALS. Feldman and her colleagues (2022) have

suspected the presence of what they call the “ALS exposome,” which is the sum of toxic environmental exposures, including prolonged exposures to organic chemical pollutants, metals, pesticides, particulate matter in dust from construction work, and generally poor air quality. Over time, the cumulative impact of genetic factors and prolonged exposure to toxic occupational and environmental exposures and lifestyle factors, such as years of alcohol consumption, higher cigarette pack years of use, and intense physical activity (common in military service), may heighten the risk of ALS.

The duration of military service and, relatedly, rank when leaving the military may also contribute to posttransition outcomes. One outcome for which this is evident is suicide risk. Evidence from longitudinal cohort studies shows that, on average, this increases upon separating from the military (Reger et al., 2015). However, it is elevated among those who served less than 2 years and members of the active (versus reserve) component (Ravindran et al., 2020). The character of service determination also is important, and suicide risk is also elevated among those who did not have an honorable discharge (Reger et al., 2015).

To help veterans transition to civilian life, VA and other federal agencies also offer programs and services such as DoD’s Transition Assistance Program, developed through the National Defense Authorization Act of 1990 after the first Gulf War and mandatory reductions in force after it; it was revised in 2011 to support individuals as they were leaving the service and focused largely on finding postmilitary employment, education, and benefits. Such programs could mitigate the stressors during transition. A review of the program found a limited focus on areas such as adjusting to new work/educational/cultural settings, meeting family transition needs, managing finances, securing adequate housing, managing trauma responses, and similar issues; the authors suggested a new model to address these gaps (Whitworth et al., 2020). The Government Accountability Office has also found DoD could improve participation in and results of the program (GAO, 2022).

Employment

When one leaves the military also has implications. In particular, those who left after 2001 may have done so during two U.S. recessions: the Great Recession from 2007 to 2009, during which the unemployment rate rose to 10% (Cunningham, 2018), and the brief spike in unemployment during the COVID-19 pandemic (Falk et al., 2021). During the Great Recession, post-9/11 veteran unemployment rates were higher than those of civilians, suggesting that perhaps some struggled to find jobs (IOM, 2013; Schwam and Marrone, 2023). A Pew Research Center report found that a majority

of veterans said military service was useful for skills and training for nonmilitary employment, and among those post-9/11 veterans without a job lined up, more than half were able to find employment in less than 6 months (Parker et al., 2019). Despite no robust literature on not finding a job upon transition and poor mental and behavioral health outcomes among service members, more broadly, losing a job is linked with new onset of or increases in mental health symptoms and some behaviors, like alcohol use (Levin et al., 2024; Ramchand et al., 2022).

Health Care

Some service members leave the military with one or more mental or physical disabilities, including the mental, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes that are the focus of this report. Those referred to the joint DoD–VA Integrated Disability Evaluation System are evaluated for whether they can return to service or be separated or retired for disability. They receive a rating on a 0–100% scale, which (in combination with their length of service) determines the amount of their disability compensation from DoD and VA, and eligibility for DoD and VA health care benefits. Veterans can apply for VA benefits and health care after they have served in other ways, determined in large part by whether their health conditions resulted from military service and/or they have economic needs. Eligibility changes often; most recently, the PACT Act2 established presumptive eligibility for veterans with certain medical conditions who deployed to certain regions at specific times—they do not need to prove that a health condition is caused by military service because it is presumed by law.

This process is described briefly because this system has implications for who receives care and whether VA provides it. First, veterans may choose not to receive any care. For veterans with “invisible wounds” in particular, many may not recognize their symptoms, not believe in mental health treatment, or distrust the mental health system (Ein et al., 2024); perceived stigma around mental health care may be a barrier to seeking it (Hoge et al., 2004). Second, veterans may elect not to receive any care at VA. Ninety-seven percent of veterans have health insurance coverage, but only one-third are enrolled in VA (Wagner et al., 2024). Veterans who present with chronic pain or screen positive for PTSD and depression have been found more likely to link to VHA care than those who do not present with chronic pain or positive PTSD and depression screenings (Adams et al., 2021; Vanneman et al., 2017). Thus, many veterans with the conditions of interest do not receive care at VA—these tend to be in better health and

___________________

2 PL 117-168.

with higher income (Wagner et al., 2024). Even 75% of veterans enrolled in VA have other forms of health insurance and may thus only receive some of their care from VA facilities. As discussed in Chapter 4, the committee’s analysis relies on VA encounter data, thus representing only a share of all veterans.

According to a 2016 profile, fewer post-9/11 veterans enrolled in VA and then used VA health care than other veterans (NCVAS, 2018). Studies of the use and nonuse of health care programs and services by post-9/11 veterans within the first 3 months of their transition to civilian life suggest that those from junior enlisted ranks, who are most at risk for poor transitions, were much less likely to use programs and services than those from higher ranks (Aronson et al., 2020), though those exposed to combat were more likely to use VA health care services. They have found that men often report not needing health care or social service programs, and women or those from the lowest enlisted ranks are more likely to report not knowing if they are eligible for support programs (Aronson et al., 2019).

Social Support and Community

Researchers, practitioners, and policy makers who work with military members and veterans recognize the need to understand and respond to the role of culture and cultural dynamics and their influence on the transition process and readjustment to postservice life. Many experience the military environment as a family that provided them with support, norms, values, and structure—all of which influence their identity (Ahern et al., 2015; Castro and Kintzle, n.d.; Cooper et al., 2018); loss of this identity can be distressing (Markowitz et al., 2023). When service members leave the military, with its structure, comradery, and other protective influences of a community, mental and behavioral health issues may become more prominent (Larson et al., 2012; Teeters et al., 2017). For example, reported drug use increases after leaving active service, with marijuana accounting for most drug use: 3.5% reporting use and 1.7% reporting use of other drugs in a 1-month period. More than 10% of veteran admissions to substance use treatment centers were for heroin, followed by cocaine at just over 6% (SAMHSA, 2015; Teeters et al., 2017). The return to civilian life can also be marked by alienation, isolation, social disconnection, and difficulties within personal relationships, further threatening the social connections and support that promote health and psychosocial well-being (Ahern et al., 2015; Demers, 2011; ODPHP, n.d.). Extensive literature has linked military-related PTSD in veterans to relationship problems, including higher divorce rates, poorer family adjustment, greater intimacy-related anxiety, less self-disclosure and emotional expressiveness, and psychological and physical aggression (Creech et al., 2019; Monson et al., 2009). Furthermore, studies

have linked relationship breakups to substance use among veterans and noted that they appear to be a prominent factor on the path to homelessness (Hamilton et al., 2011; Metraux et al., 2017).

Place of Residence and Homelessness

Among the general population, the community in which one lives is an important component of health; this is no different for veterans (NASEM, 2017). Approximately 2.7 million veterans enrolled in VHA reside in rural communities, which can have positive benefits, like lower cost of living, but also brings challenges related to access to quality health care, nutrition, and educational resources (VA, n.d.), especially as more than half of them are age 65+. Post-9/11 veterans make up an increasing share of rural veterans (VA, n.d.). Veterans returning to rural communities who live near or work in agriculture may be exposed to chemicals (e.g., pesticides, fertilizer) that increase risk for some of the committee’s outcomes of interest (Curl et al., 2020).

In a study of over 750,000 veterans who had used VHA services within the past 3 years, rural veterans had significantly more physical health conditions but fewer mental health conditions than urban and suburban veterans (Weeks et al., 2004). In a 2023 analysis of data on veterans with sleep disorders and comorbid conditions, although the prevalence of diagnosed sleep disorders during FY 2010–2021 was similar among rural and urban veterans, rural veterans had a higher prevalence of three comorbid conditions: chronic pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, and diabetes mellitus. The analysis also found that from 2012 to 2021, the percentage of rural veterans who received sleep-related care at VA facilities was lower than that for urban veterans, which suggests that rurality creates disparities in access to care (Folmer et al., 2023). Data from the 2008–2009 National Survey of Women Veterans also illustrate worse physical health among rural compared to urban veterans (Cordasco et al., 2016).

On the other hand, data suggest that rural residence may be a protective factor for mental health. In a 2020 study of veterans in central and northeastern Pennsylvania with at least one warzone deployment, rural veterans had lower global mental health severity scores and fewer mental health-related visits (Boscarino et al., 2020). However, contradictory data exist from veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn living in Hawaii, illustrating that rural veterans were more likely to meet screening criteria for mental health conditions, including PTSD and alcohol use problems (Whealin et al., 2014).

VA and various community partners have made dramatic progress in reducing veteran homelessness over the past decade (O’Toole et al., 2024; Tsai et al., 2021), but many veterans remain at risk. In 2024, veterans

accounted for approximately 5% of all U.S. adults experiencing homelessness, and this proportion was the same among all unsheltered homeless adults (De Sousa and Henry, 2024). Forty-seven percent of all veterans experiencing homelessness are in one of the nation’s 50 largest cities, and major cities account for a larger share of the unsheltered veteran population. Homelessness is associated with a host of clinical and environmental factors that may have preceded and/or followed initial episodes of it.

Studies of veterans in the VA health care system have reported much higher rates of diagnosed mental health conditions and SUD among homeless than housed veterans (O’Toole et al., 2013; Tsai et al., 2025). Veterans experiencing homelessness, particularly those unsheltered and staying in places not meant for human habitation, may be exposed to various pollutants and toxicants in their surroundings. They may also experience challenges with accessing clean water and practicing clean hygiene behaviors, given either limited access to or reliance on public facilities and shelters (Anthonj et al., 2024; Tsai and Wilson, 2020). Depending on geography, they may also be exposed to extreme weather conditions, including heat, cold, and natural disasters, that negatively affect their health (Kidd et al., 2021; Schwarz et al., 2022). All of these factors may influence the outcomes of interest. However, despite some veterans on one end of the spectrum of homelessness and housing instability, the majority of veterans in the general population live in households that have lower housing cost burdens and enjoy greater housing security overall than nonveterans (Andrew et al., 2025).

SUMMARY

This chapter discusses factors relevant to the possible relationships between military environmental and occupational exposures experienced during deployment to Southwest Asia or Afghanistan and the mental, behavioral, and neurologic health outcomes of interest among post-9/11 U.S. veterans, who are the focus of this report. The committee considered factors across a service member’s life and time in the military, including those before, during (including the deployment cycle of pre-deployment, deployment, and postdeployment), and after service, including periods of separation, transition to civilian life, and postservice. Where data are available, some of these factors are accounted for in the committee’s analyses; this information is the committee’s approach to understanding the confluence of factors potentially increasing risk of the outcomes.

REFERENCES

Adams, R. S., E. J. Dietrich, J. C. Gray, C. S. Milliken, N. Moresco, and M. J. Larson. 2019. Post-deployment screening in the military health system: An opportunity to intervene for possible alcohol use disorder. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 38(8):1298–1306.

Adams, R. S., J. E. Forster, J. L. Gradus, C. A. Hoffmire, T. A. Hostetter, M. J. Larson, C. G. Walsh, and L. A. Brenner. 2022. Time-dependent suicide rates among army soldiers returning from an Afghanistan/Iraq deployment, by military rank and component. Injury Epidemiology 9(1):46.

Adams, R. S., E. L. Meerwijk, M. J. Larson, and A. H. S. Harris. 2021. Predictors of Veterans Health Administration utilization and pain persistence among soldiers treated for postdeployment chronic pain in the military health system. BMC Health Services Research 21(1):494.

Ahern, J., M. Worthen, J. Masters, S. A. Lippman, E. J. Ozer, and R. Moos. 2015. The challenges of Afghanistan and Iraq veterans’ transition from military to civilian life and approaches to reconnection. PLoS ONE 10(7):e0128599.

Al-Chalabi, A., and O. Hardiman. 2013. The epidemiology of ALS: A conspiracy of genes, environment and time. Nature Reviews Neurology 9(11):617–628.

Andrew, M., D. Schwam, and V. Parks. 2025. The local geography of housing cost burden: Advantages and disadvantages among veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Anthonj, C., K. I. H. Mingoti Poague, L. Fleming, and S. Stanglow. 2024. Invisible struggles: Wash insecurity and implications of extreme weather among urban homeless in high-income countries—a systematic scoping review. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 255:114285.

APHC (Army Public Health Center). n.d. Lead-Based Paint in Military Housing: A Fact Sheet for Military Families. https://ph.health.mil/PHC%20Resource%20Library/LeadFactSheet_FamMem_FS_66-015-0918.pdf (accessed May 28, 2025).

Aronson, K. R., D. F. Perkins, N. Morgan, J. Bleser, K. Davenport, D. Vogt, L. A. Copeland, E. P. Finley, and C. L. Gilman. 2019. Going it alone: Post-9/11 veteran nonuse of healthcare and social service programs during their early transition to civilian life. Journal of Social Service Research 45(5):634–647.

Aronson, K. R., D. F. Perkins, N. R. Morgan, J. A. Bleser, D. Vogt, L. A. Copeland, E. P. Finley, and C. L. Gilman. 2020. Use of health services among post-9/11 veterans with mental health conditions within 90 days of separation from the military. Psychiatric Services 71(7):670–677.

Barroso, A. 2019. The Changing Profile of the U.S. Military: Smaller in Size, More Diverse, More Women in Leadership. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/09/10/the-changing-profile-of-the-u-s-military/ (accessed May 28, 2025).

Beaver, K. M., J. C. Barnes, J. A. Schwartz, and B. B. Boutwell. 2015. Enlisting in the military: The influential role of genetic factors. SAGE Open 5(2).

Blosnich, J. R., M. E. Dichter, C. Cerulli, S. V. Batten, and R. M. Bossarte. 2014. Disparities in adverse childhood experiences among individuals with a history of military service. JAMA Psychiatry 71(9):1041–1048.

Boscarino, J. J., C. R. Figley, R. E. Adams, T. G. Urosevich, H. L. Kirchner, and J. A. Boscarino. 2020. Mental health status in veterans residing in rural versus non-rural areas: Results from the Veterans’ Health Study. Military Medical Research 7(1):44.

Bove, F. J., A. Greek, R. Gatiba, B. Kohler, R. Sherman, G. T. Shin, and A. Bernstein. 2024. Cancer incidence among Marines and Navy personnel and civilian workers exposed to industrial solvents in drinking water at U.S. Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune: A cohort study. Environmental Health Perspectives 132(10):107008.

Bovin, M. J., A. Schneiderman, P. A. Bernhard, S. Maguen, C. A. Hoffmire, J. R. Blosnich, B. N. Smith, R. Kulka, and D. Vogt. 2023. Development and validation of a brief warfare exposure measure among U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans: The Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory-2 Warfare Exposure—Short Form (DRRI-2 WE-SF). Psychological Trauma 15(8):1248–1258.

Bremner, J. D., K. Moazzami, M. T. Wittbrodt, J. A. Nye, B. B. Lima, C. F. Gillespie, M. H. Rapaport, B. D. Pearce, A. J. Shah, and V. Vaccarino. 2020. Diet, stress and mental health. Nutrients 12(8):2428.

Bryan, C. J., J. E. Griffith, B. T. Pace, K. Hinkson, A. O. Bryan, T. A. Clemans, and Z. E. Imel. 2015. Combat exposure and risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors among military personnel and veterans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 45(5):633–649.

Caforio, G. 2014. Psychological problems and stress faced by soldiers who operate in asymmetric warfare environments: Experiences in the field. Journal of Defense Resources Management 5(2):23–42.

Cameron, K. L., S. W. Marshall, R. X. Sturdivant, and A. E. Lincoln. 2012. Trends in the incidence of physician-diagnosed mild traumatic brain injury among active duty U.S. military personnel between 1997 and 2007. Journal of Neurotrauma 29(7):1313–1321.

Canetto, S. S., and I. Sakinofsky. 1998. The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 28(1):1–23.

Caponnetto, P., M. Casu, M. Amato, D. Cocuzza, V. Galofaro, A. La Morella, S. Paladino, K. Pulino, N. Raia, F. Recupero, C. Resina, S. Russo, L. M. Terranova, J. Tiralongo, and M. C. Vella. 2021. The effects of physical exercise on mental health: From cognitive improvements to risk of addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(24):13384.

Carr, M. M., M. N. Potenza, K. L. Serowik, and R. H. Pietrzak. 2021. Race, ethnicity, and clinical features of alcohol use disorder among U.S. military veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. American Journal on Addictions 30(1):26–33.

Carr, W., A. L. Kelley, C. F. Toolin, and N. S. Weber. 2020. Association of MOS-based blast exposure with medical outcomes. Frontiers in Neurology 11:619.

Carter, S. P., A. A. Smith, and C. Wojtaszek. 2017. Who will fight? The all-volunteer army after 9/11. American Economic Review 107(5):415–419.

Castro, C. A., and S. Kintzle. n.d. Military Matters: The Military Transition Theory: Rejoining Civilian Life. https://istss.org/military-matters-the-military-transition-theory-rejoining-civilian-life-carl-andrew-castro-phd-and-sara-kintzle-phd-lmsw/ (accessed June 2, 2025).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2020. Percentage of adults aged ≥20 years who had chronic pain, by veteran status and age group—National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2019. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report 69(1797).

Cooper, L., N. Caddick, L. Godier, A. Cooper, and M. Fossey. 2018. Transition from the military into civilian life: An exploration of cultural competence. Armed Forces & Society 44(1):156–177.

Cordasco, K. M., M. A. Mengeling, E. M. Yano, and D. L. Washington. 2016. Health and health care access of rural women veterans: Findings from the National Survey of Women Veterans. Journal of Rural Health 32(4):397–406.

Cordes, M. F., A. E. Ahmed, and D. E. Singer. 2025. Psychological distress in active-duty U.S. service members who utilized mental health services: Data from a 2018 DoD survey. Journal of Affective Disorders 379:884–888.

Cramm, H., M. A. McColl, A. B. Aiken, and A. Williams. 2019. The mental health of military-connected children: A scoping review. Journal of Child and Family Studies 28(7):1725–1735.

Creech, S. K., J. K. Benzer, E. C. Meyer, B. B. DeBeer, N. A. Kimbrel, and S. B. Morissette. 2019. Longitudinal associations in the direction and prediction of PTSD symptoms and romantic relationship impairment over one year in post 9/11 veterans: A comparison of theories and exploration of potential gender differences. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 128(3):245–255.

Cunningham, E. 2018. Great Recession, Great Recovery? Trends from the Current Population Survey. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2018/article/great-recession-great-recovery.htm (accessed June 2, 2025).

Curl, C. L., M. Spivak, R. Phinney, and L. Montrose. 2020. Synthetic pesticides and health in vulnerable populations: Agricultural workers. Current Environmental Health Reports 7(1):13–29.

Davis, J. P., W. S. Livingston, R. K. Landis, and R. Ramchand. 2025. Alcohol Use Disorder Among U.S. Veterans. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA1363-14.html (accessed July 16, 2025).

De Sanctis, V., N. Soliman, A. T. Soliman, H. Elsedfy, S. Di Maio, M. El Kholy, and B. Fiscina. 2017. Caffeinated energy drink consumption among adolescents and potential health consequences associated with their use: A significant public health hazard. Acta Biomedica 88(2):222–231.

De Sousa, T., and M. Henry. 2024. The 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress: Part 1: Point-in-time estimates of homelessness. Washington, DC: Office of Policy Development and Research, Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Demers, A. 2011. When veterans return: The role of community in reintegration. Journal of Loss and Trauma 16(2):160–179.

DoD (Department of Defense). 2018. DoD instruction 6130.03, volume 1 medical standards for military service: Appointment, enlistment, or induction. Washington, DC: Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, Department of Defense.

DoD. 2020. DoD instruction 6130.03, volume 2 medical standards for military service: Retention. Washington, DC: Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, Department of Defense.

DoD SAPRO (Department of Defense Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office). 2024. Fact Sheet: Fiscal Year 2023 (FY23) Department of Defense (DoD) Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/public/docs/reports/AR/FY23/FY23_Annual_Report_Fact_Sheet.pdf (accessed May 28, 2025).

Doucette, C. E., N. R. Morgan, K. R. Aronson, J. A. Bleser, K. J. McCarthy, and D. F. Perkins. 2023. The effects of adverse childhood experiences and warfare exposure on military sexual trauma among veterans. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 38(3–4):3777–3805.

Ein, N., J. Gervasio, K. St. Cyr, J. J. W. Liu, C. Baker, A. Nazarov, and J. D. Richardson. 2024. A rapid review of the barriers and facilitators of mental health service access among veterans and their families. Frontiers in Health Services 4:1426202.

Falk, G., I. A. Nicchitta, E. C. Nyhof, and P. D. Romero. 2021. Unemployment rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Feldman, E. L., S. A. Goutman, S. Petri, L. Mazzini, M. G. Savelieff, P. J. Shaw, and G. Sobue. 2022. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 400(10360):1363–1380.

Folmer, R. L., C. J. Smith, E. A. Boudreau, A. M. Totten, P. Chilakamarri, C. W. Atwood, and K. F. Sarmiento. 2023. Sleep disorders among rural veterans: Relative prevalence, comorbidities, and comparisons with urban veterans. The Journal of Rural Health 39(3):582–594.

Forrest, W., B. Edwards, and G. Daraganova. 2018. The intergenerational consequences of war: Anxiety, depression, suicidality, and mental health among the children of war veterans. International Journal of Epidemiology 47(4):1060–1067.

Gallaway, M. S., M. R. Bell, C. Lagana-Riordan, D. S. Fink, C. E. Meyer, and A. M. Millikan. 2013. The association between U.S. Army enlistment waivers and subsequent behavioral and social health outcomes and attrition from service. Military Medicine 178(3):261–266.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2022. Servicemembers Transitioning to Civilian Life: DoD Can Better Leverage Performance Information to Improve Participation in Counseling Pathways. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-104538 (accessed June 2, 2025).

Good, C. H., A. J. Brager, V. F. Capaldi, and V. Mysliwiec. 2020. Sleep in the United States military. Neuropsychopharmacology 45(1):176–191.

Haley, R. W. 1998. Point: Bias from the “healthy-warrior effect” and unequal follow-up in three government studies of health effects of the Gulf War. American Journal of Epidemiology 148(4):315–323.

Hamilton, A. B., I. Poza, and D. L. Washington. 2011. “Homelessness and trauma go hand-in-hand”: Pathways to homelessness among women veterans. Women’s Health Issues 21(4):S203–S209.

Health.mil. 2024a. Adjustments After Deployment. https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Mental-Health/Mental-Health-Topics/Adjustments-After-Deployment (accessed June 2, 2025).

Health.mil. 2024b. Update: Diagnoses of Mental Health Disorders Among Active Component U.S. Armed Forces, 2019–2023. https://www.health.mil/News/Articles/2024/12/01/MSMR-Mental-Health-Update-2024 (accessed May 28, 2025).

Health.mil. 2025. Medical Evaluation Board. https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Access-Cost-Quality-and-Safety/DES/Medical-Evaluation (accessed June 2, 2025).

Helmick, K. M., C. A. Spells, S. Z. Malik, C. A. Davies, D. W. Marion, and S. R. Hinds. 2015. Traumatic brain injury in the U.S. military: Epidemiology and key clinical and research programs. Brain Imaging and Behavior 9(3):358–366.

Herbert, M. S., D. W. Leung, J. O. E. Pittman, E. Floto, and N. Afari. 2018. Race/ethnicity, psychological resilience, and social support among OEF/OIF combat veterans. Psychiatry Research 265:265–270.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services) Task Force on Black and Minority Health. 1985. Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health.

Hobfoll, S. E., C. D. Spielberger, S. Breznitz, C. Figley, S. Folkman, B. Lepper-Green, D. Meichenbaum, N. A. Milgram, I. Sandler, I. Sarason, and B. van der Kolk. 1991. War-related stress: Addressing the stress of war and other traumatic events. American Psychologist 46(8):848–855.

Hoffmire, C. A., L. L. Monteith, J. E. Forster, P. A. Bernhard, J. R. Blosnich, D. Vogt, S. Maguen, A. A. Smith, and A. I. Schneiderman. 2021. Gender differences in lifetime prevalence and onset timing of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among post-9/11 veterans and nonveterans. Medical Care 59:S84–S91.

Hoge, C. W., J. L. Auchterlonie, and C. S. Milliken. 2006. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 295(9):1023–1032.

Hoge, C. W., C. A. Castro, S. C. Messer, D. McGurk, D. I. Cotting, and R. L. Koffman. 2004. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine 351(1):13–22.

Holder, K. A. 2018. They Are Half the Size of the Living Vietnam Veteran Population. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/04/post-9-11-veterans.html (accessed May 28, 2025).

Hourani, L. L., T. V. Williams, and A. M. Kress. 2006. Stress, mental health, and job performance among active duty military personnel: Findings from the 2002 Department of Defense Health-Related Behaviors Survey. Military Medicine 171(9):849–856.

Hughes, K., M. A. Bellis, K. A. Hardcastle, D. Sethi, A. Butchart, C. Mikton, L. Jones, and M. P. Dunne. 2017. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2(8):e356–e366.

Ikin, J. F., M. R. Sim, D. P. McKenzie, K. W. A. Horsley, E. J. Wilson, M. R. Moore, P. Jelfs, W. K. Harrex, and S. Henderson. 2007. Anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in Korean War veterans 50 years after the war. British Journal of Psychiatry 190(6):475–483.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2013. Returning home from Iraq and Afghanistan: Assessment of readjustment needs of veterans, service members, and their families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

James, A. A., and K. O’Shaughnessy. 2023. Environmental chemical exposures and mental health outcomes in children: A narrative review of recent literature. Frontiers in Toxicology 5:1290119.

Jannace, K. C., L. Pompeii, D. Gimeno Ruiz de Porras, W. B. Perkison, J.-M. Yamal, D. W. Trone, and R. P. Rull. 2025. Risk of traumatic brain injury in deployment and nondeployment settings among members of the Millennium Cohort study. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 40(2):E102–E110.

Katon, J. G., K. Lehavot, T. L. Simpson, E. C. Williams, S. B. Barnett, J. R. Grossbard, M. B. Schure, K. E. Gray, and G. E. Reiber. 2015. Adverse childhood experiences, military service, and adult health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 49(4):573–582.

Kennedy, J. N., V. S. Bebarta, S. M. Varney, L. A. Zarzabal, and V. J. Ganem. 2015. Prescription stimulant misuse in a military population. Military Medicine 180(suppl_3):191–194.

Kidd, S. A., S. Greco, and K. McKenzie. 2021. Global climate implications for homelessness: A scoping review. Journal of Urban Health 98(3):385–393.

King, D. W., L. A. King, D. M. Gudanowski, and D. L. Vreven. 1995. Alternative representations of war zone stressors: Relationships to posttraumatic stress disorder in male and female Vietnam veterans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 104(1):184–196.

Kornblith, E., A. Bahorik, W. J. Boscardin, F. Xia, D. E. Barnes, and K. Yaffe. 2022. Association of race and ethnicity with incidence of dementia among older adults. JAMA 327(15):1488–1495.

Larson, M. J., N. R. Wooten, R. S. Adams, and E. L. Merrick. 2012. Military combat deployments and substance use: Review and future directions. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions 12(1):6–27.

LeardMann, C. A., T. M. Powell, T. C. Smith, M. R. Bell, B. Smith, E. J. Boyko, T. I. Hooper, G. D. Gackstetter, M. Ghamsary, and C. W. Hoge. 2013. Risk factors associated with suicide in current and former U.S. military personnel. JAMA 310(5):496–506.

Levin, C., S. Nenninger, D. Freundlich, S. Glatt, and Y. Sokol. 2024. How future self-continuity mediates the impact of job loss on negative mental health outcomes among transitioning veterans. Military Psychology 36(5):491–503.

Lopez, A. A., R. L. Toblin, L. A. Riviere, J. D. Lee, and A. B. Adler. 2018. Correlates of current and heavy smoking among U.S. soldiers returning from combat. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 26(3):215–222.

Lopez, C. T. 2023. All-Volunteer Force Proves Successful for U.S. Military. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/article/3316678/all-volunteer-force-proves-successful-for-us-military/ (accessed June 4, 2025).

Luxton, D. D., N. A. Skopp, and S. Maguen. 2010. Gender differences in depression and PTSD symptoms following combat exposure. Depression and Anxiety 27(11):1027–1033.

Maguen, S., D. D. Luxton, N. A. Skopp, and E. Madden. 2012. Gender differences in traumatic experiences and mental health in active duty soldiers redeployed from Iraq and Afghanistan. Journal of Psychiatric Research 46(3):311–316.

Malone, L. 2014. Hiring from high-risk populations: Lessons from the U.S. military. Contemporary Economic Policy 32(1):133–143.

Markowitz, F. E., S. Kintzle, and C. A. Castro. 2023. Military-to-civilian transition strains and risky behavior among post-9/11 veterans. Military Psychology 35(1):38–49.

Matthieu, M. M., M. Meissen, A. Scheinberg, and E. M. Dunn. 2021. Reasons why post-9/11 era veterans continue to volunteer after their military service. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 61(3):405–426.

McCauley, H. L., J. R. Blosnich, and M. E. Dichter. 2015. Adverse childhood experiences and adult health outcomes among veteran and non-veteran women. Journal of Women’s Health 24(9):723–729.

Meadows, S. O., C. C. Engel, R. L. Collins, R. L. Beckman, J. Breslau, E. Litvin Bloom, M. S. Dunbar, M. Gilbert, D. Grant, J. Hawes-Dawson, S. B. Holliday, S. MacCarthy, E. R. Pedersen, M. W. Robbins, A. J. Rose, J. Ryan, T. L. Schell, and M. M. Simmons. 2021a. 2018 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS): Results for the active component. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Meadows, S. O., C. C. Engel, R. L. Collins, R. L. Beckman, J. Breslau, E. Litvin Bloom, M. S. Dunbar, M. Gilbert, D. Grant, J. Hawes-Dawson, S. B. Holliday, S. MacCarthy, E. R. Pedersen, M. W. Robbins, A. J. Rose, J. Ryan, T. L. Schell, and M. M. Simmons. 2021b. 2018 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS): Results for the reserve component. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Merians, A. N., G. Gross, M. R. Spoont, C. D. Bellamy, I. Harpaz-Rotem, and R. H. Pietrzak. 2023. Racial and ethnic mental health disparities in U.S. military veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans study. Journal of Psychiatric Research 161:71–76.

Metraux, S., M. Cusack, T. H. Byrne, N. Hunt-Johnson, and G. True. 2017. Pathways into homelessness among post-9/11-era veterans. Psychological Services 14(2):229–237.

Miles, M. R., and D. P. Haider-Markel. 2019. Personality and genetic associations with military service. Armed Forces & Society 45(4):637–658.

Milliken, C. S., J. L. Auchterlonie, and C. W. Hoge. 2007. Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA 298(18):2141–2148.

Monson, C. M., C. T. Taft, and S. J. Fredman. 2009. Military-related PTSD and intimate relationships: From description to theory-driven research and intervention development. Clinical Psychology Review 29(8):707–714.

Montes, K., and J. Weatherly. 2014. The relationship between personality traits and military enlistment: An exploratory study. Military Behavioral Health 2:98–104.

Moore, E. 2020. Women in Combat: Five-Year Status Update. https://www.cnas.org/publications/commentary/women-in-combat-five-year-status-update (accessed July 16, 2025).

Morral, A. R., and T. L. Schell. 2021. Sexual assault of sexual minorities in the U.S. military. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. Communities in action: Pathways to health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2025. Veterans, prescription opioids and benzodiazepines, and mortality, 2007–2019: Three target trial emulations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NCVAS (National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics). 2018. Profile of post-9/11 veterans: 2016. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse). 2019. General Risk of Substance Use Disorders. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/substance-use-military-life (accessed May 28, 2025).

Nieh, C., J. D. Mancuso, T. M. Powell, M. M. Welsh, G. D. Gackstetter, and T. I. Hooper. 2021. Cigarette smoking patterns among U.S. military service members before and after separation from the military. PLoS ONE 16(10):e0257539.

NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health). n.d. Schizophrenia. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia (accessed May 28, 2025).

ODPHP (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion). n.d. Social Cohesion. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/social-cohesion (accessed June 2, 2025).

OPA (Office of People Analytics). 2018. 2017 Workplace and Equal Opportunity Survey of Active Duty Members: Tabulations of responses. Alexandria, VA: Office of People Analytics, Department of Defense.

OPA. 2019. 2018 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Members: Overview report. Alexandria, VA: Office of People Analytics, Department of Defense.

Orasanu, J. M., and P. Backer. 2013. Stress and military performance. In Stress and human performance, 1st ed., edited by E. Salas, J. E. Driskell, and S. Hughes. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

O’Toole, T. P., C. Bourgault, E. E. Johnson, S. G. Redihan, M. Borgia, R. Aiello, and V. Kane. 2013. New to care: Demands on a health system when homeless veterans are enrolled in a medical home model. American Journal of Public Health 103(Suppl 2):S374–S379.

O’Toole, T. P., L. M. Pape, V. Kane, M. Diaz, A. Dunn, J. L. Rudolph, and S. Elnahal. 2024. Changes in homelessness among U.S. veterans after implementation of the Ending Veteran Homelessness Initiative. JAMA Network Open 7(1):e2353778.

Parker, K., R. Igielnik, A. Barroso, and A. Cilluffo. 2019. The American veteran experience and the post-9/11 generation. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Paxton Willing, M. M., L. L. Tate, K. G. O’Gallagher, D. P. Evatt, and D. S. Riggs. 2022. In-theater mental health disorders among U.S. soldiers deployed between 2008 and 2013. Medical Surveillance Monthly Report 29(11):11–17.

Peters, Z. J., M. W. Kincaid, R. F. Quah, J. G. Greenberg, and J. C. Curry. 2019. Surveillance snapshot: Trends in opioid prescription fills among U.S. military service members during fiscal years 2007-2017. Medical Surveillance Monthly Report 26(10):21.

Pettersson, E., P. Lichtenstein, H. Larsson, J. Song, A. Agrawal, A. D. Børglum, C. M. Bulik, M. J. Daly, L. K. Davis, D. Demontis, H. J. Edenberg, J. Grove, J. Gelernter, B. M. Neale, A. F. Pardiñas, E. Stahl, J. T. R. Walters, R. Walters, P. F. Sullivan, D. Posthuma, and T. J. C. Polderman. 2019. Genetic influences on eight psychiatric disorders based on family data of 4,408,646 full and half-siblings, and genetic data of 333,748 cases and controls. Psychological Medicine 49(7):1166–1173.

Phillips, D. 2024a. Chronic Brain Trauma Is Extensive in Navy’s Elite Speedboat Crews. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/12/us/brain-trauma-cte-navy-speedboat.html (accessed June 2, 2025).

Phillips, D. 2024b. Signs of Brain Injury in Mortar Soldiers: “Guys Are Getting Destroyed.” https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/12/us/brain-trauma-cte-navy-speedboat.html (accessed June 2, 2025).

Phillips, D. 2024c. Top-Gun Navy Pilots Fly at the Extremes. Their Brains May Suffer. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/08/us/navy-pilot-brain-injury-topgun.html (accessed June 2, 2025).

Ramchand, R., T. L. Schell, B. R. Karney, K. C. Osilla, R. M. Burns, and L. B. Caldarone. 2010. Disparate prevalence estimates of PTSD among service members who served in Iraq and Afghanistan: Possible explanations. Journal of Traumatic Stress 23(1):59–68.

Ramchand, R., T. L. Schell, L. H. Jaycox, and T. Tanielian. 2011. Epidemiology of trauma events and mental health outcomes among service members deployed to iraq and afghanistan. In Caring for veterans with deployment-related stress disorders: Iraq, Afghanistan, and beyond, edited by J. I. Ruzek, P. P. Schnurr, J. J. Vasterling, and M. J. Friedman. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Ramchand, R., R. Rudavsky, S. Grant, T. Tanielian, and L. Jaycox. 2015. Prevalence of, risk factors for, and consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems in military populations deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Current Psychiatry Reports 17(5):37.

Ramchand, R., L. Ayer, and S. O’Connor. 2022. Unemployment, Behavioral Health, and Suicide. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/briefs/unemployment-behavioral-health-and-suicide (accessed June 2, 2025).

Ramchand, R., K. M. Williams, and C. M. Farmer. 2023. “Conditions for postservice success are set well before the uniform comes off”: Proceedings from a roundtable on how military service affects veterans’ posttransition outcomes. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

RAND. 2008. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

RAND. 2016. The Deployment Life Study: Longitudinal analysis of military families across the deployment cycle. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Ravindran, C., S. W. Morley, B. M. Stephens, I. H. Stanley, and M. A. Reger. 2020. Association of suicide risk with transition to civilian life among U.S. military service members. JAMA Network Open 3(9):e2016261.

Reger, M. A., D. J. Smolenski, N. A. Skopp, M. J. Metzger-Abamukang, H. K. Kang, T. A. Bullman, S. Perdue, and G. A. Gahm. 2015. Risk of suicide among U.S. military service members following Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom deployment and separation from the U.S. military. JAMA Psychiatry 72(6):561–569.

Reuben, A., A. Caspi, D. W. Belsky, J. Broadbent, H. Harrington, K. Sugden, R. M. Houts, S. Ramrakha, R. Poulton, and T. E. Moffitt. 2017. Association of childhood blood lead levels with cognitive function and socioeconomic status at age 38 years and with IQ change and socioeconomic mobility between childhood and adulthood. JAMA 317(12):1244–1251.

Robinson, E., J. W. Lee, T. Ruder, M. S. Schuler, G. Wenig, C. M. Farmer, J. Phillips, and R. Ramchand. 2023. A summary of veteran-related statistics. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2015. Veterans’ Primary Substance of Abuse Is Alcohol in Treatment Admissions. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_2111/Spotlight-2111.html (accessed June 2, 2025).

Sanders, J. W., S. D. Putnam, C. Frankart, R. W. Frenck, M. R. Monteville, M. S. Riddle, D. M. Rockabrand, T. W. Sharp, and D. R. Tribble. 2005. Impact of illness and non-combat injury during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 73(4):713–719.

Schell, T. L., and G. N. Marshall. 2008. Chapter 4: Survey of individuals previously deployed for OEF/OIF. In Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery, edited by T. Tanielian and L. H. Jaycox. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Schwam, D., and J. V. Marrone. 2023. Veterans’ Employment During Recessions. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA1363-7.html (accessed June 2, 2025).