Exploring Military Exposures and Mental, Behavioral, and Neurologic Health Outcomes Among Post-9/11 Veterans (2025)

Chapter: 6 Results for Mental and Behavioral Health Outcomes

6

Results for Mental and Behavioral Health Outcomes

This chapter describes the mental and behavioral health outcomes of interest and presents the results of the case-control studies and structured literature review. These outcomes include adjustment disorders; attention disorders; anxiety disorders; depression; posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); serious mental illness (SMI), which includes psychosis and schizophrenia spectrum disorders and bipolar disorder; sleep disorders; substance use disorders (SUD)1; and nonfatal suicide attempts and intentional self-harm. Criteria to prioritize results of the statistical analyses presented in this chapter are an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of at least 1.10 and the exclusion of 1.0 in the 95% confidence interval (CI). The chapter also includes conclusions on possible relationships between mental and behavioral health outcomes and deployment-related environmental and occupational exposures. In addition, the chapter presents results of stratified analyses and a cumulative exposure analysis. Although traumatic brain injury (TBI) was specified as an outcome in the Statement of Task, because TBI is not caused by military exposures by definition, the committee instead treated it as a covariate and stratified each exposure–outcome pair by TBI status. For these results, the committee prioritized reporting those in which the adjusted ORs between strata were different, at least one stratum’s OR was above 1.0 and the lower bound of the 95% CI was also above 1.0, and the

___________________

1 SUD includes alcohol-related disorders; opioid-related disorders; cannabis-related disorders; sedative-, hypnotic-, or anxiolytic-related disorders; cocaine-related disorders; other stimulant-related disorders; hallucinogen-related disorders; nicotine dependence; inhalant-related disorders; and other psychoactive substance–related disorders.

95% CIs did not overlap between strata. Cumulative exposure analyses were based on additive counts of individual binary exposures. The chapter presents results of these analyses when there was evidence of a trend of increased risk with increasing exposure. Full results of all data analyses are in Appendix G.

Due to time constraints, the committee undertook its structured literature search before obtaining data on exposures from the Individual Longitudinal Exposure Record (ILER); therefore, the search is not directly based on each of the exposure categories available for its analyses (see Chapter 4 for more information). For example, ILER data contained exposures for dust and particulate matter (PM), exhaust, and incinerator emissions, while the search was conducted for PM because it is a component of these exposures and has a robust literature base. Additionally, burn pits have been known to be associated with other component pollutants, such as PM, dust, metals, volatile organic compounds, and fuels (IOM, 2011). The committee has detailed literature search results in sections for some of these specific components of burn pit exposure pollutants, even if there were no specific studies on burn pits identified in the search. Furthermore, studies in the search were not limited to those about onset of new disease but rather could have measured incidence, prevalence, changes in symptom severity, or mortality related to an outcome. Chapter 4 describes how the committee integrated evidence from its statistical analyses with the search results to draw its conclusions. The committee cautions again that the results presented are based on a sample of post-9/11 veterans who served in Southwest Asia or Afghanistan and received care at Veterans Health Administration (VHA), so the sample used for its analyses has limited generalizability. All conclusions should be interpreted as specific to this population.

ADJUSTMENT DISORDERS

Adjustment disorders refer to emotional or behavioral symptoms that occur within 3 months of a psychosocial stressor. Symptoms are similar to those of other affective disorders like depression or anxiety, such as generalized impairment or difficulty dealing with a specific stressor, but do not persist for more than an additional 6 months (O’Donnell et al., 2019). Symptoms or behaviors are clinically significant in that they cause marked distress and significant impairment in functioning. Population-based studies in Europe have reported low rates (about 1%) of adjustment disorders (Gradus, 2017). However, much higher rates have been reported among high-risk populations with known and specific psychosocial stressors, such as those who are unemployed (27%), are bereaved (18%), or have psychiatric conditions and other medical illnesses (O’Donnell et al., 2019).

Due to the physical and emotional demands of military life, including

high rates of trauma exposure, adjustment disorders are among the most commonly diagnosed mental health disorders among active-duty service members (DHA, 2024). They accounted for more than three in 10 incident mental health diagnoses between 2016 and 2020 (Military Health System, 2021). Using administrative and TRICARE electronic health record (EHR) data, their prevalence was found to be 6.2% in 2021 and 7.6% in 2022 (Curry et al., 2025). Prevalence rates are similarly high among some post-9/11 U.S. veterans—4.1% in women and 3.5% in men, based on Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) electronic health data from 163,812 Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF)/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF)2 veterans between 2001 and 2007 (Haskell et al., 2011). Importantly, diagnoses of adjustment disorders are also known to be a predictor of linkage to VHA care, particularly among service members with chronic pain, and may precede other mental health diagnoses and can mediate risk of suicide among those with TBI (Adams et al., 2021; Brenner et al., 2023).

Analysis Results

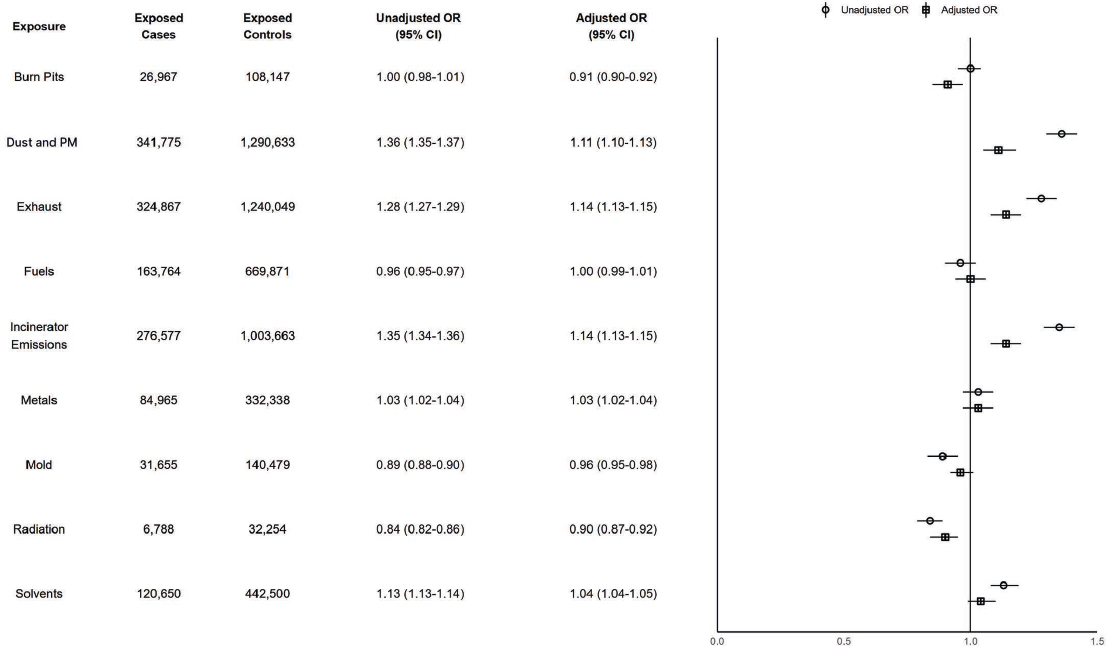

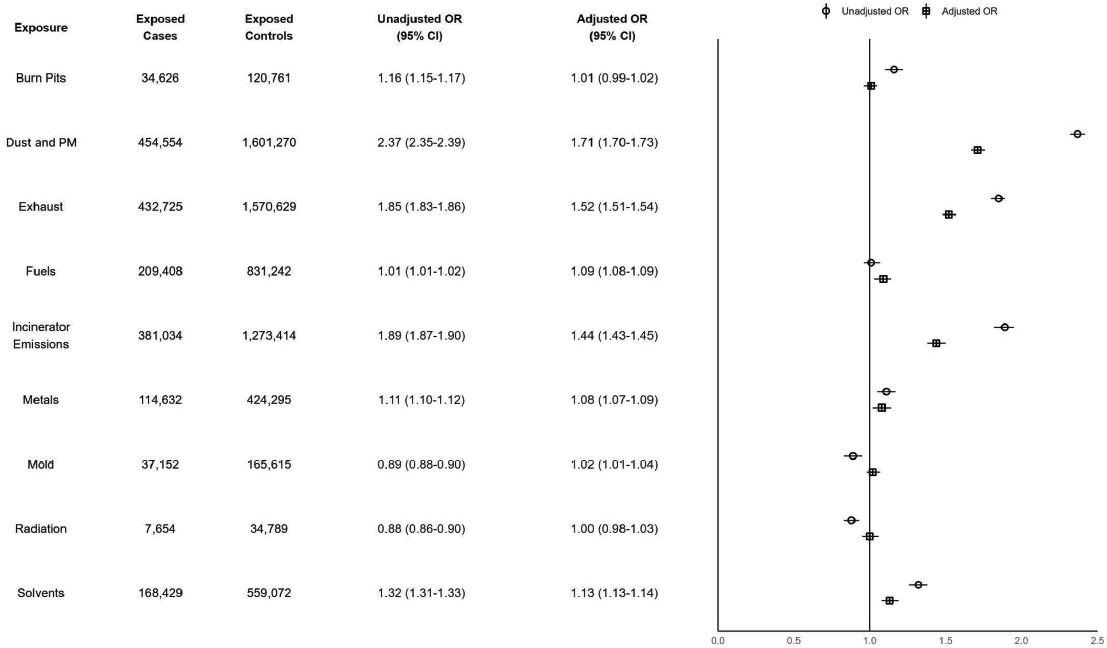

There were 423,877 cases (37.0%) of adjustment disorders. Figure 6-1 shows that exposure to dust and PM, exhaust, and incinerator emissions is associated with a risk-conferring relationship with adjustment disorder, with adjusted ORs of 1.11 (95% CI: 1.10–1.13), 1.14 (95% CI:1.13–1.15), and 1.14 (95% CI: 1.13–1.15), respectively. Odds of adjustment disorders associated with all three exposures were elevated for those both with and without TBI. Additionally, stratified analyses identified differences in the magnitude of association. The associations with dust and PM, exhaust, and incinerator emissions are 14.1%, 9.1%, and 6.7% higher, respectively, for people without TBI. Additionally, increasing number of exposures (compared to zero) was generally associated with elevated risk, despite no synergy among exposure groupings.

Literature Search Results

PM and Adjustment Disorders

One cohort study that pooled data from six European countries found a positive but not significant association between long-term exposure to PM2.5 and mortality from psychiatric disorders, which the authors defined as a broad range of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9)- and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10)-coded mental and behavioral disorders, including adjustment disorders

___________________

2 OEF was the military operation in Afghanistan October 7, 2001–December 28, 2014. OIF was the military operation in Iraq March 19, 2003–August 31, 2010.

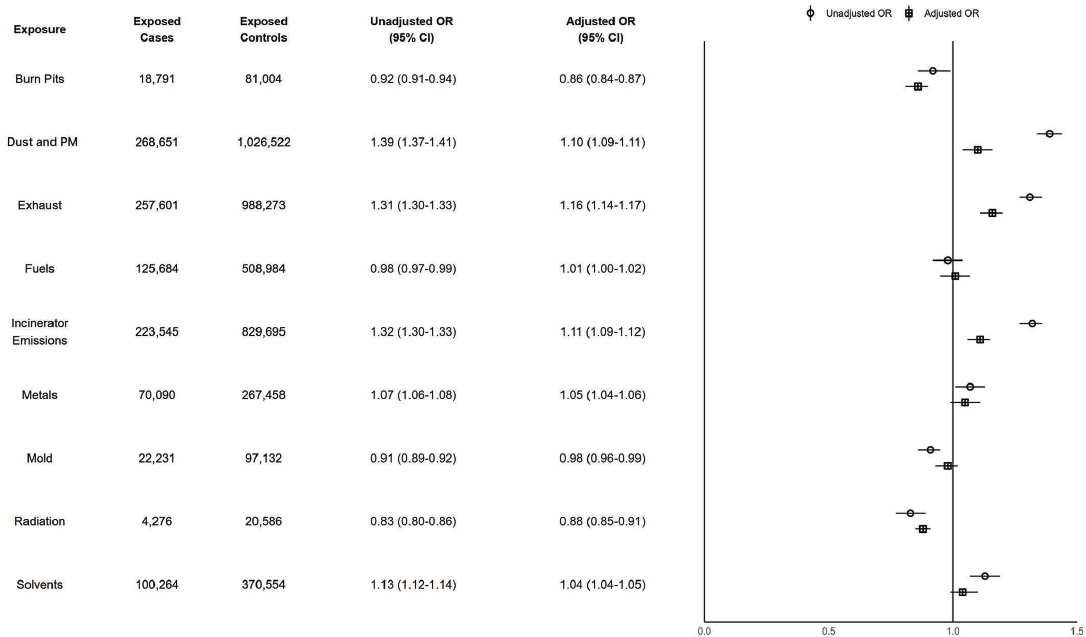

NOTES: Exposed cases n = 423,877; exposed controls n = 1,649,584. CI = confidence interval; ILER = Individual Longitudinal Exposure Record; OR = odds ratio; PM = particulate matter.

(Andersen et al., 2022). The authors found long-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide and black carbon were positively associated with psychiatric disorder mortality; ozone was negatively associated with mortality, but this association attenuated and was no longer significant after adjusting for other pollutants.

Metals and Adjustment Disorders

One cohort study that pooled data from six European countries found no association between long-term exposure to seven metal and metalloid components of PM2.5 (copper, iron, nickel, potassium, silicon, vanadium, and zinc) and mortality from psychiatric disorders, which the authors defined as a broad range of ICD-9- and ICD-10-coded mental and behavioral disorders, including adjustment disorders (Andersen et al., 2022).

Burn Pits, Fuels, Mold, Radiation, or Solvents and Adjustment Disorders

The search yielded zero results on the possible relationships between exposure to burn pits, fuels, mold, radiation, or solvents and the risk of adjustment disorders.

Conclusion

Conclusion 6-1: Based on its analysis of the available data, the committee finds there is a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to dust and particulate matter (PM), exhaust, or incinerator emissions and adjustment disorders. The committee does not find a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, fuels, metals, mold, radiation, or solvents and adjustment disorders.

Based on the literature review, there is insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to PM or metals and adjustment disorders. There is no identified literature on the relationship between exposure to burn pits, fuels, mold, radiation, or solvents and adjustment disorders.

Synthesizing the committee’s data analysis and literature review, the committee concludes there is a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to dust and PM, exhaust, or incinerator emissions and adjustment disorders. The committee further concludes there is inadequate or insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, fuels, metals, mold, radiation, or solvents and adjustment disorders.

ATTENTION DISORDERS

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder of executive functions beginning in childhood that can continue into adulthood. ADHD is characterized by persistent patterns of inattention (e.g., not following instructions, trouble organizing tasks), and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity (such as being unable to sit still, talking excessively). To be diagnosed in adulthood, individuals must have experienced symptoms before age 12 and exhibit at least five persistent symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity-impulsivity in at least two different contexts (home, school, or work) (NIMH, 2021). Attention-deficit disorder (ADD) had similar symptomology but was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and is no longer used for diagnosis, although it remains in common parlance (Epstein and Loren, 2013). ICD codes for both ADHD and ADD are included in the committee’s analyses.

Several studies have estimated ADHD prevalence in the general population. A subsample of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, a nationally representative face-to-face survey conducted during 2001–2003, estimated the U.S prevalence of adult ADHD at 4.4% (Kessler et al., 2004, 2006). A meta-analysis of global studies found that the prevalence of persistent adult ADHD and symptomatic adult ADHD were 2.58% and 6.76%, respectively, in 2020 (Song et al., 2021).

Estimates for ADHD prevalence in veteran and military populations are higher than those reported in the general population. A retrospective cohort study found an age-adjusted annual prevalence of 0.84% among VA patients during 2009–2016 (Hale et al., 2020), but one study of 21,449 active-duty soldiers screened for ADHD found a prevalence of 7.6–9.0% depending on the diagnostic criteria used (Kok et al., 2019). Another study of a representative sample of nondeployed U.S. Army personnel found a prevalence of 7.0% (Kessler et al., 2014).

Analysis Results

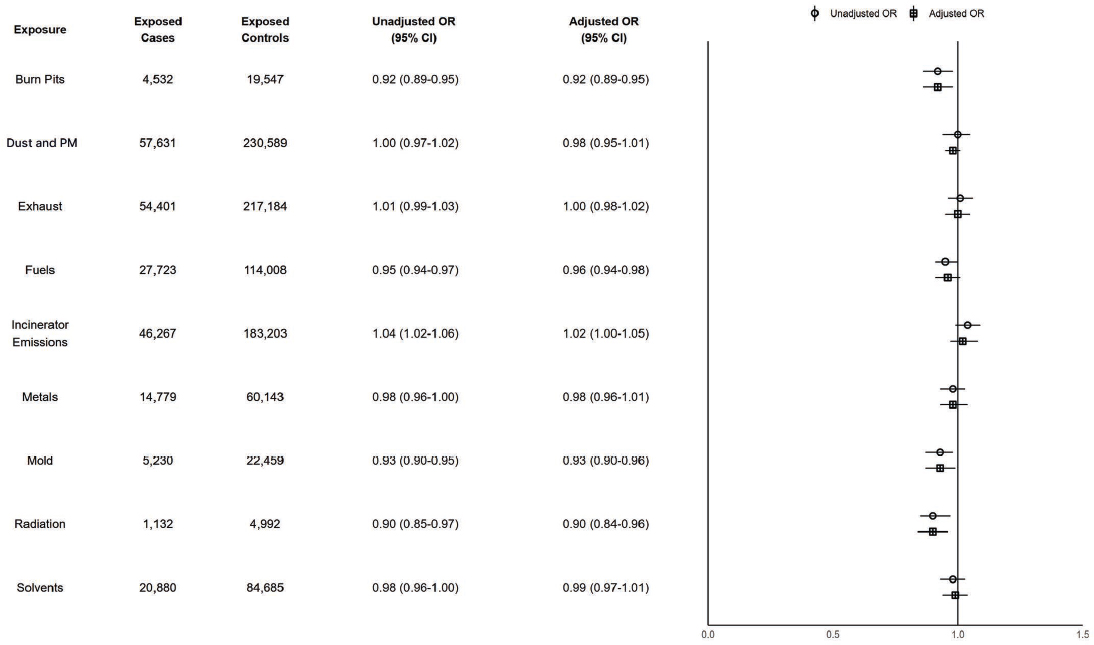

There were 70,310 cases (6.1%) of attention disorders. In Figure 6-2, none of the adjusted ORs and associated CIs for the exposures and attention disorders met the prioritization criteria for additional discussion. All exposures had no differences in the magnitude of association when stratifying by TBI, which suggests no interaction between these exposures and TBI on odds of attention disorders.

Literature Search Results

Because attention disorders are frequently diagnosed in adolescence and the bulk of the evidence base on these and environmental exposures is

NOTES: Exposed cases n = 70,310; exposed controls n = 281,217. CI = confidence interval; ILER = Individual Longitudinal Exposure Record; OR = odds ratio; PM = particulate matter.

among adolescents, this literature search included adolescents. This differs from the searches for the other outcomes of interest, which were limited to adults or people 18 years and older. Most studies of environmental exposures and ADHD diagnoses identified were among adolescent populations.

PM and Attention Disorders

Eight studies in the literature search investigated the relationship between PM and ADHD, most of which were in children and/or adolescents; none included specific military or veteran populations. The results included one meta-analysis (Zhang et al., 2022), three systematic reviews (Aghaei et al., 2019; Donzelli et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2024a), and four other study types (Andersen et al., 2022; Park et al., 2020; Shim et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2024) and they examined PM overall, PM2.5, PM10, and other specific air pollutants.

The studies that considered air pollution and/or PM overall did not find consistent association between exposure and ADHD. For example, the meta-analysis of nine studies did not find exposure to PM significantly increased risk of ADHD (Zhang et al., 2022), while one systematic review found the majority of included studies reported positive association between PM exposure and behavioral problems in children related to attention (Donzelli et al., 2020). Another systematic review stated that more studies reported an association between PM and air pollution and ADHD than did not but overall concluded there was limited evidence that exposure is linked to increased risk of ADHD (Aghaei et al., 2019). The meta-analysis found no publication bias and exclusion of lower quality studies did not change the results, but the authors note studies were limited and heterogeneous (Zhang et al., 2022); Donzelli and colleagues (2020) also highlight the small number of studies, high heterogeneity, and a high risk of publication bias.

The studies that examined PM2.5 and PM10 exposures had more consistent results, with more evidence for PM10. Another systematic review of eight studies found some evidence that prenatal exposure to PM2.5 increased ADHD risk and reported more evidence that postnatal exposure increases risk (Zhao et al., 2024a). This finding is complemented by Zhu and colleagues (2024), who found genetically predicted PM2.5 exposure significantly increased risk of ADHD among adults in a two-sample Mendelian randomization study using publicly available genome-wide association study3 data, though this effect could have been confounded by other air pollutants. The Zhao and colleagues (2024a) systematic review

___________________

3 A genome-wide association study compares complete sets of subjects’ DNA and differences in the genome while also investigating other factors’ effects on an outcome, such that genetics (and often other factors) can be compared as exposures.

also highlighted the growing body of evidence that postnatal exposure to PM10 increases risk of developing ADHD. Similarly, a time-series analysis of South Korean adolescents indicates short-term exposure to PM10 significantly increased risk of hospital admissions for ADHD (Park et al., 2020), and another study also using South Korean data found exposure to long-term PM10 was significantly associated with higher odds of ADHD among children and adolescents (Shim et al., 2022). Finally, a cohort study that pooled data from six European countries found a positive but not significant association between long-term exposure to PM2.5 and mortality from psychiatric disorders, which the authors defined as a broad range of ICD-9- and ICD-10-coded mental and behavioral disorders, including attention disorders (Andersen et al., 2022).

Five of these studies also provided results for other specific air pollutants, with the most evidence about nitrogen dioxide. While the Aghaei and colleagues (2019) review did not find consistent evidence of an association between nitrogen dioxide and ADHD, the Zhao and colleagues (2024a) review discussed an overall indication of the association when exposed postnatally, and Park and colleagues (2020) found short-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide significantly increased risk of ADHD-related hospital admissions, particularly among older adolescents. The Park and colleagues (2020) study also found short-term exposure to sulfur dioxide significantly increased risk of these hospital admissions. Aghaei and colleagues (2019) reported more studies found a significant association between black and elemental carbon and ADHD than did not. Results from the meta-analysis and two of the reviews were not significant or were inconsistent for the association of nitrogen oxides and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and ADHD among children (Aghaei et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2024a). Finally, Andersen and colleagues (2022) found long-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide and black carbon were positively associated with psychiatric disorder mortality; ozone was negatively associated with mortality, but this association attenuated and was no longer significant after adjusting for other pollutants.

Metals and Attention Disorders

The literature search yielded a meta-analysis (Dimitrov et al., 2024), a systematic review (Farmani et al., 2024), and a cohort study (Andersen et al., 2022) of metals and attention disorders; none were specific to military or veteran populations, and the meta-analysis and review focused on children. Results for lead were consistent. The meta-analysis found childhood (but not prenatal) exposure to lead was significantly associated with higher odds of ADHD symptoms and diagnosis (Dimitrov et al., 2024); the systematic review also found most observational studies on lead reported

significant associations with symptoms of one or more ADHD subtypes (Farmani et al., 2024). However, results for mercury were mixed: the meta-analysis found significant associations between prenatal and childhood exposure to mercury and ADHD (Dimitrov et al., 2024), while the systematic review reported most studies did not find a significant association between mercury exposure and any type of ADHD (Farmani et al., 2024). Finally, Dimitrov and colleagues (2024) did not find a significant association between cadmium exposure and ADHD.

The cohort study that pooled data from six European countries found no association between long-term exposure to seven metal and metalloid components of PM2.5 (copper, iron, nickel, potassium, silicon, vanadium, and zinc) and mortality from psychiatric disorders, which the authors defined as a broad range of ICD-9- and ICD-10-coded mental and behavioral disorders, including attention disorders (Andersen et al., 2022).

Mold and Attention Disorders

The literature search yielded one study on mold and attention disorders (Casas et al., 2013). The study did not include military or veteran populations and instead focused on children in two German population-based birth cohorts. The authors did not find a significant association between parent-reported indoor visible mold and a parent-reported measure of children’s hyperactivity/inattention.

Burn Pits, Fuels, Radiation, or Solvents and Attention Disorders

The committee’s search yielded zero results on the possible relationships between exposure to burn pits, fuels, radiation, or solvents and the risk of attention disorders.

Conclusion

Conclusion 6-2: Based on its analysis of the available data, the committee does not find a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, dust and particulate matter (PM), exhaust, fuels, incinerator emissions, metals, mold, radiation, or solvents and attention disorders.

Based on the literature review, there is mixed evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to PM or metals and attention disorders. There is insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to mold and attention disorders. There is no identified literature on the relationship

between exposure to burn pits, fuels, radiation, or solvents and attention disorders.

Synthesizing the committee’s data analysis and literature review, the committee concludes there is inadequate or insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, dust and PM, exhaust, fuels, incinerator emissions, metals, mold, radiation, or solvents and attention disorders.

ANXIETY DISORDERS

Anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder) are common and can affect daily functioning. Generalized anxiety disorder is defined by persistent feelings of anxiety (restlessness, irritability, feeling on edge, being easily fatigued, etc.) or dread beyond normal episodic anxiety that disrupts daily activities for at least 6 months (NIMH, 2025). In the 2019 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), an annual, cross-sectional, nationally representative household survey, 15.6% of respondents reported anxiety symptoms within the prior 2 weeks (Terlizzi and Villarroel, 2020). The Mental and Substance Use Disorders Prevalence Study (MDPS), which conducted clinical interviews with 5,679 participants between 2020 and 2022 to provide prevalence estimates of specific mental health disorders in the U.S. adult population, found 10.0% of working-age U.S. adults with generalized anxiety disorder (Ringeisen et al., 2023).

The prevalence of anxiety among veteran populations appears higher than that in the general U.S. population. The 2019–2020 National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study, a survey of a large nationally representative sample of U.S. veterans used to estimate the prevalence and sociodemographic factors contributing to anxiety, found that among all veterans (not just those enrolled in VA care), 22.1% screened positive for probable mild anxiety symptoms and 7.9% for probable generalized anxiety disorder (Macdonald-Gagnon et al., 2024). A study of questionnaires and chart reviews at VA primary care clinics found that 12% of veterans met diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorders (Milanak et al., 2013). A more recent study of approximately 5.4 million VA primary care users nationally found gender differences in prevalence of anxiety disorders: 7.2% among men and 14.1% among women (Leung et al., 2020).

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by repeated unwanted and uncontrollable intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and potentially repeated behaviors (compulsions) often in response to the unwanted thoughts (NIMH, 2023a). The unwanted thoughts often cause anxiety in people with OCD (NIMH, 2023a). While OCD is distinct from an anxiety disorder, the committee included OCD outcomes within the category of

anxiety disorders in its analysis due to the common symptom of anxiety among those with OCD.

Analysis Results

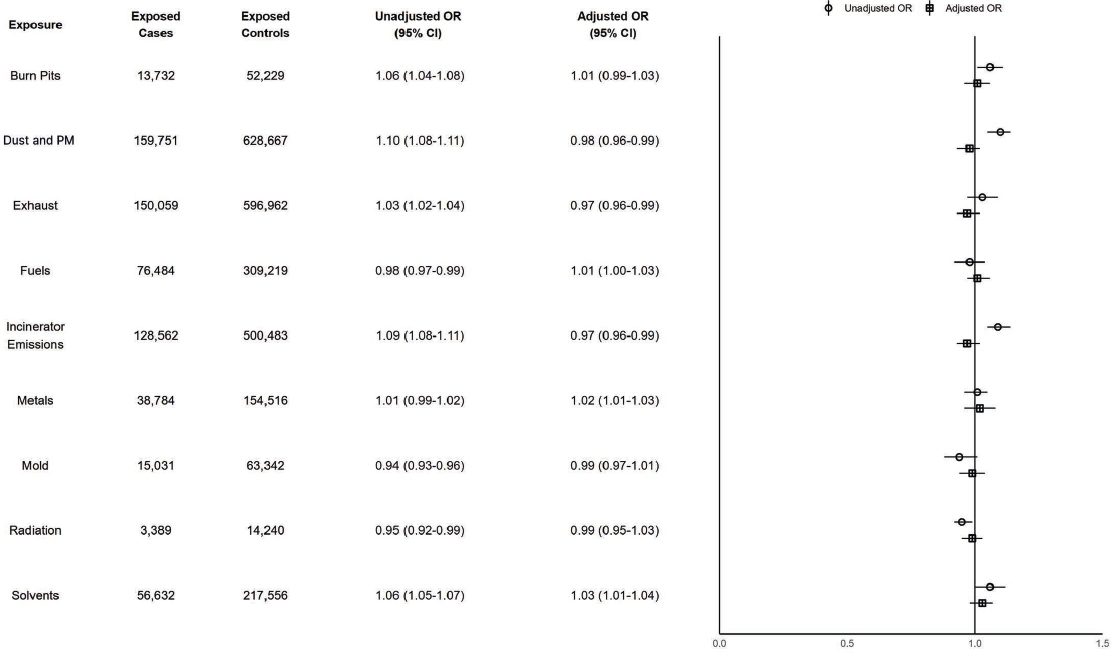

There were 199,477 cases (17.4%) of anxiety disorders. In Figure 6-3, none of the adjusted ORs and associated CIs for the exposures and anxiety disorders met the prioritization criteria for additional discussion. All exposures had no differences in the magnitude of association when stratifying by TBI, which suggests no interaction between these exposures and TBI on odds of anxiety disorders.

Literature Search Results

PM and Anxiety Disorders

The search yielded 10 studies that examined the association between PM exposure and anxiety, including two meta-analyses (Cao et al., 2024; Trushna et al., 2021), two systematic reviews (Braithwaite et al., 2019; Zundel et al., 2022), and six other types of studies (Andersen et al., 2022; Bakolis et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2023; Gao et al., 2023; Nobile et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2024). No study was specific to military or veteran populations, and the studies investigated exposure to air pollution generally or a combination of air pollutants, PM2.5, PM10, and other specific pollutants, with mixed results.

One review of air pollution generally, including PM2.5, PM10, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, and diesel exhaust particles, found most studies on internalizing psychopathology, including anxiety, depression, and suicide outcomes, were on PM2.5, PM10, and nitrogen dioxide (Zundel et al., 2022). Almost three-quarters (73%) of the review’s included studies found an association between exposure to air pollution and greater internalizing symptoms and behaviors. One-quarter of the studies reported no significant association (14%) or mixed results (11%; i.e., significant for one outcome but not the other), and 2% found decreased internalizing symptoms or behaviors following air pollution exposure. Similarly, a cross-sectional study using an air pollution index of combined pollutants (PM2.5, PM10, PMcoarse, nitrogen dioxide, nitrogen oxides) found significantly higher odds of a joint depression–anxiety outcome associated with long-term exposure (Gao et al., 2023).

Results for PM2.5 alone were mixed. Two meta-analyses of a small number of studies reported no association between PM2.5 exposure and anxiety disorder (Cao et al., 2024; Trushna et al., 2021); authors note high heterogeneity among included studies. This finding was echoed in a

NOTES: Exposed cases n = 199,477; exposed controls n = 797,666. CI = confidence interval; ILER = Individual Longitudinal Exposure Record; OR = odds ratio; PM = particulate matter.

cross-sectional study in London (Bakolis et al., 2021) and in an ecological study of wildfire-related PM2.5 in California (Chen et al., 2023). Additionally, a cohort study that pooled data from six European countries found a positive but not significant association between long-term exposure to PM2.5 and mortality from psychiatric disorders, which the authors defined as a broad range of ICD-9- and ICD-10-coded mental and behavioral disorders, including anxiety disorders (Andersen et al., 2022). However, four other studies did find a significant association. The review by Braithwaite and colleagues (2019) concluded short- and long-term exposure to PM2.5 was significantly associated with anxiety symptoms, though this was based on just two studies. A large longitudinal cohort study in Italy also found long-term PM2.5 associated with slightly higher risk of anxiety disorders (Nobile et al., 2023). The study by Gao and colleagues (2023) also found small but significantly higher odds of anxiety among participants exposed to PM2.5 at baseline and similarly small but significantly increased risk of incident anxiety after several years. Finally, genetically predicted PM2.5 exposure was significantly associated with higher odds of anxiety among adults in a two-sample Mendelian randomization study using publicly available genome-wide association study data, though this effect could have been confounded by other air pollutants (Zhu et al., 2024).

Studies of PM10 were similarly mixed, with the Trushna and colleagues (2021) meta-analysis finding a protective effect (which the authors note could have been due to confounding), the Gao and colleagues (2023) cross-sectional study finding a significant positive effect, and the Bakolis and colleagues (2021) study finding no association of PM10 exposure with anxiety.

Results for other specific air pollutants were also inconsistent or only included in one study, except for black carbon. Nobile and colleagues (2023) found a positive association between black carbon and anxiety; Andersen and colleagues (2022) reported long-term exposure to black carbon was positively associated with psychiatric disorder mortality. Exposure to nitrogen dioxide was negatively (Trushna et al., 2021), positively (Gao et al., 2023; Nobile et al., 2023), or not (Bakolis et al., 2021) associated with anxiety, and nitrogen oxides were either positively associated (Gao et al., 2023) with anxiety or null (Bakolis et al., 2021). Null results were also reported for PMcoarse (Gao et al., 2023). Ozone was negatively associated with psychiatric disorder mortality, but this association attenuated and was no longer significant after adjusting for other pollutants (Andersen et al., 2022).

Metals and Anxiety Disorders

The literature search identified six studies that assessed the association between metals and anxiety disorders, including one systematic review (Cybulska et al., 2021), a cohort study (Andersen et al., 2022), and four

cross-sectional studies (Chen et al., 2024; Gui et al., 2023; Islam et al., 2013; Racette et al., 2021), none of which were specific to military or veteran populations. The studies included a variety of metals with mixed results.

The review of lead and cadmium found a mix of results for the association between lead and anxiety, and no included studies reported an association between cadmium and anxiety (Cybulska et al., 2021). However, two cross-sectional studies using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data found urinary cadmium was significantly associated with self-reported anxiety (Gui et al., 2023) and serum cadmium was significantly associated with self-reported anxiety in current smokers in a linear dose-response pattern (Chen et al., 2024). Both of these studies also found cadmium was associated with increased anxiety when included in metals mixtures: with cobalt, antimony, uranium, and tungsten (Gui et al., 2023) and playing the largest role with lead, mercury, selenium, and manganese (Chen et al., 2024). Gui and colleagues (2023) did not find an association with lead and anxiety.

In two other studies of manganese, one cross-sectional study did not show significant differences in anxiety scores between unexposed and exposed residential areas (near a manganese smelter) (Racette et al., 2021), but another cross-sectional study found participants with anxiety had significantly higher serum manganese than participants without anxiety (Islam et al., 2013).

In terms of other metals and metalloids studied, urinary antimony and urinary cobalt at the highest level were associated with increased odds of self-reported anxiety (Gui et al., 2023). Islam and colleagues (2013) also found participants with anxiety had significantly lower serum zinc and higher copper and iron than those without anxiety. No association was found between anxiety and barium, molybdenum, thallium, cesium, selenium, calcium, and magnesium (Chen et al., 2024; Gui et al., 2023; Islam et al., 2013). A cohort study that pooled data from six European countries found no association between long-term exposure to seven metal and metalloid components of PM2.5 (copper, iron, nickel, potassium, silicon, vanadium, and zinc) and mortality from psychiatric disorders, which the authors defined as a broad range of ICD-9- and ICD-10-coded mental and behavioral disorders, including anxiety disorders (Andersen et al., 2022).

Radiation and Anxiety Disorders

A systematic review and meta-analysis of low-to-moderate exposure to ionizing radiation on mortality from a heterogenous composite measure of mental and behavioral disorders, which included anxiety disorders, found a significantly lower mortality of such disorders among the exposed populations compared to the general population (Lopes et al., 2022); the authors note this result may be explained by the healthy worker effect.

Burn Pits, Fuels, Mold, or Solvents and Anxiety Disorders

The committee’s search yielded zero results on possible relationships between exposure to burn pits, fuels, mold, or solvents and the risk of anxiety disorders.

Conclusion

Conclusion 6-3: Based on its analysis of the available data, the committee does not find a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, dust and particulate matter (PM), exhaust, fuels, incinerator emissions, metals, mold, radiation, or solvents and anxiety disorders.

Based on the literature review, there is mixed evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to PM or metals and anxiety disorders. There is inadequate and insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to radiation and anxiety disorders. There is no identified literature on the relationship between exposure to burn pits, fuels, mold, or solvents and anxiety disorders.

Synthesizing the committee’s data analysis and literature review, the committee concludes there is inadequate or insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, dust and PM, exhaust, fuels, incinerator emissions, metals, mold, radiation, or solvents and anxiety disorders.

DEPRESSION

Depression is common, varies in severity, and can affect daily activities, like sleep, work, or appetite. Major depressive disorder is a serious mood disorder consisting of symptoms like depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, weight loss or gain, insomnia or hypersomnia, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness, diminished ability to concentrate or indecisiveness, and/or recurrent thoughts of death, lasting longer than 2 weeks (APA, 2013). Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, an annual nationally representative survey sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, determined the 2021 prevalence of depression among U.S. adults aged 18 years or older as 8.3% (NIMH, 2024b). The MDPS also found high rates—for example, prevalence of major depressive disorder was 15.5%—among U.S. adults aged 18–65, suggesting that more adults may be experiencing depression than in the past (Ringeisen et al., 2023).

Estimates of depression prevalence in the veteran population, however, appear higher than the general U.S. population, though estimates vary widely depending on the case definition and subpopulation. Among veterans generally (not only VHA users), a study using six cycles of NHANES found a prevalence of depression peak at 12.3% in 2011–2012 (Liu et al., 2019). Data from VHA health records on all patients assigned a VA primary care provider before VHA introduced a patient-centered medical home model indicated the prevalence of depression from diagnostic codes is 13.5% (Trivedi et al., 2015). Among a national cohort of 9,191,729 VHA patients who were universally administered the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 from 2018 to 2023, 7.4% reported incident depressive symptoms (Leung et al., 2024). Certain veteran subgroups appear to have higher than average rates of depression. Based on a research cohort including diagnostic interviews of 1,700 post-9/11 veterans during 2005–2012, 46.5% of female and 36.3% of male veterans had a lifetime major depressive disorder diagnosis (Curry et al., 2014).

Analysis Results

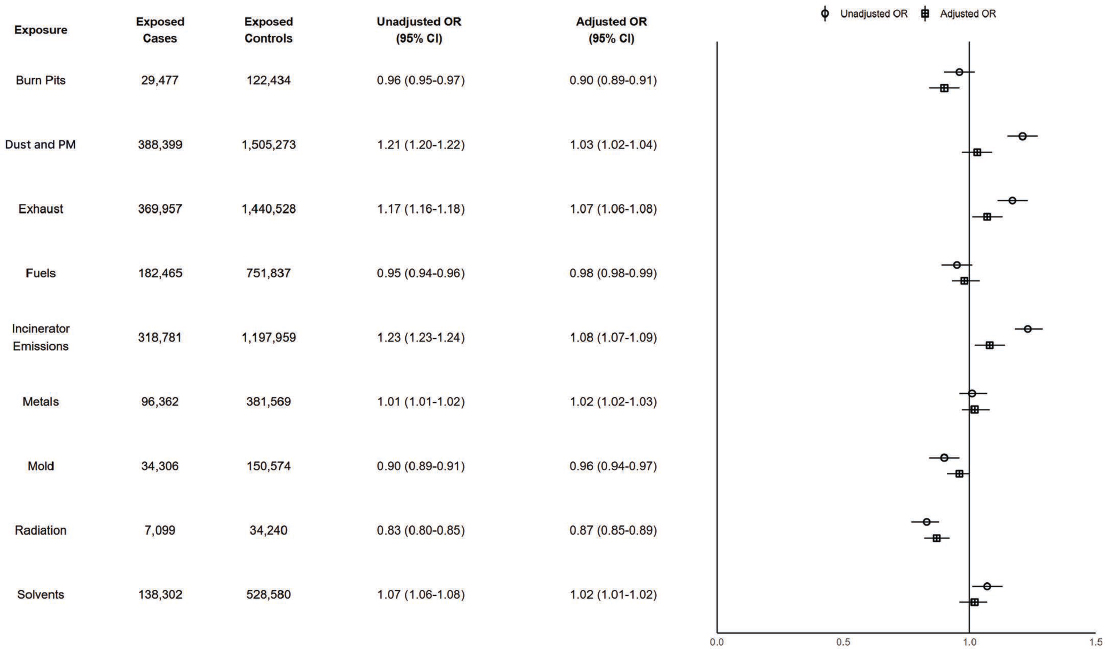

There were 473,754 cases (41.4%) depression. In Figure 6-4, none of the adjusted ORs and associated CIs for the exposures and depression met the prioritization criteria for additional discussion. Analyses stratified by TBI status indicated elevated odds of depression associated with incinerator emissions exposure among people without TBI; the association with depression is 8.2% higher than among people with TBI.

Literature Search Results

PM and Depression

The literature search yielded 16 studies on the association between PM and depression, including six meta-analyses (Borroni et al., 2022; Braithwaite et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2024; Fan et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2019), one systematic review (Zundel et al., 2022), and nine other study types (Andersen et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023; Gao et al., 2023; Hao et al., 2022; Jiang and Zhao, 2024; Nobile et al., 2023; Pignon et al., 2022; Qiu et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2024). None of the studies were specific to military or veteran populations. The studies assessed air pollution overall, PM2.5, PM10, and other specific air pollutants.

Zundel and colleagues (2022) reviewed air pollution generally, including PM2.5, PM10, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, and diesel exhaust particles, and internalizing psychopathology, including anxiety, depression, and suicide outcomes. Based on the results of the majority of their included studies, the

NOTES: Exposed cases n = 473,754; exposed controls n = 1,894,163. CI = confidence interval; ILER= Individual Longitudinal Exposure Record; OR = odds ratio; PM = particulate matter.

authors concluded air pollution is associated with increased risk of internalizing symptoms and behaviors (about 25% of studies reported mixed or no association, and a small percentage found a negative association).

Most of the studies that evaluated PM2.5 found a positive association with depression. The meta-analysis of 39 studies by Borroni and colleagues (2022) found a small but significant risk-conferring association between both short- and long-term PM2.5 exposure and depression risk. The authors found some publication bias, but sensitivity analyses supported initial findings. This result is complemented by additional meta-analyses. Liu and colleagues (2021) also found a significant risk-conferring relationship between short- and long-term PM2.5 exposure and depression (with a larger magnitude of effect in the long-term exposure results). Braithwaite and colleagues’ (2019) meta-analysis of five studies also found higher long-term exposure was associated with increased odds of depression. Zeng and colleagues (2019) reported that long-term but not short-term PM2.5 exposure significantly increased risk of depression. Using 23 studies, Cao and colleagues (2024) similarly found a significant relationship between PM2.5 and depression. Among the meta-analyses, only Fan and colleagues (2020) failed to find a significant relationship between short- and long-term PM2.5 exposure and depression. The positive association found by many meta-analyses is echoed in the other study types, including the large longitudinal cohort study in Italy that found risk of depression significantly increased with long-term exposure to PM2.5 (Nobile et al., 2023); the Qiu and colleagues (2022) case-crossover study of people age 65 or older, which found short-term PM2.5 associated with increased rate of hospitalization for depression; Hao and colleagues’ (2022) cross-sectional study, which reported a significant positive relationship between PM2.5 and risk of major depression; and the Gao and colleagues (2023) study that also found a risk-conferring relationship between long-term PM2.5 exposure and odds of depression. However, two studies reported no association: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study of genetically predicted PM2.5 exposure, which reported that predicted exposure to PM2.5 did not significantly increase risk of depression (Zhu et al., 2024), and an ecological study of wildfire-specific PM2.5 in California, which did not find evidence of an association with a composite mood disorder outcome including depression and bipolar disorder (Chen et al., 2023). Additionally, a cohort study that pooled data from six European countries found a positive but not significant association between long-term exposure to PM2.5 and mortality from psychiatric disorders, which the authors defined as a broad range of ICD-9- and ICD-10-coded mental and behavioral disorders, including depression (Andersen et al., 2022).

More studies reported no evidence of an association between depression and PM10 than for PM2.5. Three meta-analyses found risk of depression or depressive symptoms significantly associated with short-term PM10 exposure

but not with long-term PM10 exposure (Borroni et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2019). Three more meta-analyses did not find a relationship with PM10 in general (Cao et al., 2024), long-term PM10 (Braithwaite et al., 2019), or short- or long-term exposure (Fan et al., 2020). In qualitative synthesis, Braithwaite and colleagues (2019) also found that three studies examining short-term exposure to PM10 and emergency department admissions for depression reported mixed results, while a fourth study found that short-term PM10 exposure was associated with an increase in reported depression symptoms in an elderly population. Similarly, PM10 peaks (days in which the daily mean level of PM was above national warning levels) were significantly associated with emergency department visits for depression in the Pignon and colleagues (2022) study, and higher levels of PM10 were associated with higher odds of depression and with risk of incident depression at follow-up in the Gao and colleagues (2023) study.

Other specific air pollutants investigated include nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, ozone, carbon monoxide, and black carbon with mixed results. Studies with nitrogen dioxide were generally consistent in reporting a risk-conferring relationship between short- or long-term exposure and risk of depression (Andersen et al., 2022; Borroni et al., 2022; Cao et al., 2024; Gao et al., 2023; Nobile et al., 2023; Qiu et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2019). Results for sulfur dioxide were mixed: two found nonsignificant results overall (Cao et al., 2024; Fan et al., 2020), one reported a significant positive association with short-term exposure and no association with long-term exposure (Zeng et al., 2019), and one reported a significant positive association with short-term exposure and a significant negative association with long-term exposure (Borroni et al., 2022). Evidence for carbon monoxide was also mixed: one meta-analysis found no association (Cao et al., 2024), one found positive associations in both short- and long-term exposures (though based on a small number of studies) (Borroni et al., 2022), and one reported a positive association with risk of depression in short-term exposure but nonsignificant results with long-term exposure (Zeng et al., 2019). There was no evidence of an association for ozone exposure in four meta-analyses (Borroni et al., 2022; Cao et al., 2024; Fan et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2019); ozone was negatively associated with psychiatric disorder mortality in Andersen and colleagues’ (2022) cohort study, but this association attenuated and was no longer significant after adjusting for other pollutants. A cross-sectional study using NHANES data found urinary metabolites of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons were significantly associated with increased risk of depression (Jiang and Zhao, 2024). Finally, Andersen and colleagues (2022) found long-term exposure to black carbon was associated with increased risk of psychiatric disorder mortality.

Metals and Depression

Six studies examined metals and depression, including one systematic review (Cybulska et al., 2021); a cohort study (Andersen et al., 2022); and four cross-sectional studies, three of which used NHANES data (Berk et al., 2014; Jiang and Zhao, 2024; Racette et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024). None of these were specific to military or veteran populations. The studies included cadmium, mercury, lead, selenium, and manganese and a mix of other metals.

Four studies found a positive association between higher cadmium and depression or depressive symptoms (Berk et al., 2014; Cybulska et al., 2021; Jiang and Zhao, 2024; Zhang et al., 2024). Two studies found higher mercury was negatively associated with depression (Berk et al., 2014; Jiang and Zhao, 2024), which authors say may be related to fish consumption. There were conflicting results for lead: two studies found a positive association (Cybulska et al., 2021; Jiang and Zhao, 2024) and two reported no significant association (Berk et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2024). The studies also included conflicting results for manganese: Racette and colleagues (2021) found participants, exposed to manganese (living in a residential area near a manganese smelter) had significantly higher depression scores than unexposed participants, but Zhang and colleagues (2024) did not find an association between serum manganese levels and depression. The Zhang and colleagues study (2024) also did not find an association with selenium.

The cohort study that pooled data from six European countries found no association between long-term exposure to seven metal and metalloid components of PM2.5 (copper, iron, nickel, potassium, silicon, vanadium, and zinc) and mortality from psychiatric disorders, which the authors defined as a broad range of ICD-9- and ICD-10-coded mental and behavioral disorders, including depression (Andersen et al., 2022).

Radiation and Depression

A retrospective cohort study of clean-up workers of the Chornobyl disaster site found a significantly elevated risk of non-psychotic organic disorders, which included depression, among those exposed to higher levels of ionizing radiation compared to the internal control group (those exposed to less than 50 millisieverts of radiation) (Loganovsky et al., 2020). Authors also found clean-up workers experienced a higher percentage of affective disorders (mainly severe depression) compared to an unexposed group.

Solvents and Depression

Two cross-sectional studies examined the relationship between occupational exposure to solvents and depression and found consistent results,

though neither included military or veteran populations (Saraei et al., 2022; Siegel et al., 2017). One study found a significant association between solvent exposure among workers at a tire factory in Iran and more depressive symptoms (Saraei et al., 2022). Siegel and colleagues (2017) also found significant associations between reported ever-use of solvents, gasoline, and petroleum distillates; long duration of any solvent use; and short-term use of petroleum distillates and a continuous score of depression among U.S. farmers in the Agricultural Health Study. The cross-sectional design of both studies limits the establishment of causality between solvent exposure and depression.

Burn Pits, Fuels, or Mold and Depression

The committee’s search yielded zero results on the possible relationships between exposure to burn pits, fuels, or mold and the risk of depression.

Conclusion

Conclusion 6-4: Based on its analysis of the available data, the committee does not find a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, dust and particulate matter (PM), exhaust, fuels, incinerator emissions, metals, mold, radiation, or solvents and depression.

Based on the literature review, there is suggestive evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to PM and depression. There is mixed evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to metals and depression. There is limited evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to solvents and depression. There is insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between radiation and depression. There is no identified literature on the relationship between exposure to burn pits, fuels, or mold and depression.

Synthesizing the committee’s data analysis and literature review, the committee concludes there is a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to PM and depression. The committee further concludes there is inadequate or insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, dust, exhaust, fuels, incinerator emissions, metals, mold, radiation, or solvents and depression.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

PTSD affects someone who was exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence and causes disturbances lasting more than one month. Symptoms usually appear within 3 months of the event and include avoidance of potential triggers, re-experiencing the traumatic memory, arousal and reactivity (such as being easily startled), and cognition and mood symptoms (such as being unable to remember specific parts of the event) (NIMH, 2023b). Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, a nationally representative face-to-face survey conducted during 2001–2003 using DSM-IV criteria, estimated the U.S. population prevalence of 3.6% in the past year; a more recent survey using the Wave 3 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC-III), a nationally representative survey, found past-year prevalence of 4.7% with DSM-5 criteria (Goldstein et al., 2016; NIMH, n.d.). Clinical interview data from MDPS found 4.1% of working-age U.S. adults had PTSD in the past year (Ringeisen et al., 2023). Lifetime prevalence of PTSD among the general population is estimated between 6.0 and 6.8% (Goldstein et al., 2016; NIMH, n.d.).

Rates are higher among veteran than nonveteran U.S. adults, even though PTSD in veterans can be difficult to diagnose due to the avoid-ant nature of some symptoms (Lawson, 2014). Based on the NESARC-III survey, lifetime prevalence of PTSD among U.S. veterans is 7% (Schnurr, 2025). Interviews with a sample at outpatient VA medical centers estimated the current prevalence at 11.5% (Magruder et al., 2005). A study of approximately 5.4 million VA primary care users nationally found gender differences in prevalence of PTSD—11.4% among men and 15.0% among women in 2014 (Leung et al., 2020). There is also evidence that female veterans may have higher prevalence of PTSD due to additional risks to their exposure to specific traumas (Lehavot et al., 2018). Additionally, a meta-analysis of studies of OEF/OIF veterans published during 2007–2013 estimated much higher average prevalence (23%) in this cohort of veterans (Fulton et al., 2015).

Analysis Results

There were 514,125 cases (44.9%) of PTSD. Figure 6-5 shows that exposure to dust and PM, exhaust, incinerator emissions, and solvents is associated with a risk-conferring relationship with PTSD; adjusted ORs are 1.71 (95% CI: 1.70–1.73), 1.52 (95% CI: 1.51–1.54), 1.44 (95% CI: 1.43–1.45), and 1.13 (95% CI: 1.13–1.14), respectively. Sensitivity analyses of the same analysis were conducted in a cohort of VHA users identified as serving post-9/11 using an alternate indicator (post-9/11 service and combat service indicators) to control for combat exposure; the corresponding adjusted ORs for dust and PM, exhaust, incinerator emissions, and

NOTES: Exposed cases n = 514,125; exposed controls n = 2,055,806. CI = confidence interval; ILER = Individual Longitudinal Exposure Record; OR = odds ratio; PM = particulate matter; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

solvents exhibit risk-conferring associations. Odds of PTSD associated with dust and PM and exhaust were elevated in both TBI and non-TBI strata. Additionally, exposure to dust and PM and exhaust and PTSD are 20.3% and 9.5% higher, respectively, among people with TBI. Increasing number of exposures (compared to zero) was generally associated with elevated risk of PTSD.

Literature Search Results

PM and PTSD

One cohort study that pooled data from six European countries found a positive but not significant association between long-term exposure to PM2.5 and mortality from psychiatric disorders, which the authors defined as a broad range of ICD-9- and ICD-10-coded mental and behavioral disorders, including PTSD (Andersen et al., 2022). The authors found long-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide and black carbon were positively associated with psychiatric disorder mortality; ozone was negatively associated with mortality, but this association attenuated and was no longer significant after adjusting for other pollutants.

Metals and PTSD

One cohort study that pooled data from six European countries found no association between long-term exposure to seven metal and metalloid components of PM2.5 (copper, iron, nickel, potassium, silicon, vanadium, and zinc) and mortality from psychiatric disorders, which the authors defined as a broad range of ICD-9- and ICD-10-coded mental and behavioral disorders, including PTSD (Andersen et al., 2022).

Burn Pits, Fuels, Mold, Radiation, or Solvents and PTSD

The search yielded zero results on possible relationships between exposure to burn pits, fuels, mold, radiation, or solvents and the risk of PTSD.

Conclusion

Conclusion 6-5: Based on its analysis of the available data, the committee finds there is a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to dust and particulate matter (PM), exhaust, incinerator emissions, or solvents and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The committee does not find a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, fuels, metals, mold, or radiation and PTSD.

Based on the literature review, there is insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to PM or metals and PTSD. There is no identified literature on the relationship between exposure to burn pits, fuels, mold, radiation, or solvents and PTSD.

Synthesizing the committee’s data analysis and literature review, the committee concludes there is a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to dust and PM, exhaust, incinerator emissions, or solvents and PTSD. The committee further concludes there is inadequate or insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, fuels, metals, mold, or radiation and PTSD.

SERIOUS MENTAL ILLNESS: SCHIZOPHRENIA, PSYCHOSIS, AND BIPOLAR DISORDER

SMI is defined as a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder resulting in serious functional impairment, which substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities (NIMH, 2024d). It is therefore not restricted to a specific diagnosis, and definitions of SMI and included diagnoses may vary in different structures and settings. The committee includes three conditions in its category of SMI: psychosis, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

Psychosis is not a diagnosis per se but a set of symptoms wherein the individual has experienced some loss of contact with reality, such as delusion and hallucinations, and may have other symptoms, such as nonsensical speech and inappropriate behaviors (NIMH, 2023c). Psychosis has no single cause and symptoms can occur without a co-occurring mental health condition, though psychosis can also be a symptom of physical illnesses or mental illnesses, like bipolar disorder or depression (NIMH, 2023c). Notably, a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophrenia spectrum disorders (which also includes schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders and delusional disorder) requires psychotic symptoms (APA, 2024b; Fowles, 2003). Schizophrenia is also accompanied by negative symptoms such as loss of motivation and executive functioning, catatonia, reduced focus, and reduced decision-making capabilities (NIMH, 2024c). Emerging research indicates that it may not be a single distinct disease but rather represents a segment of a broader schizophrenia or psychosis spectrum (Cuthbert and Morris, 2021). In contrast, a diagnosis of bipolar disorder does not require psychosis; it is characterized by periods of unusually intense emotion marked by manic episodes, wherein a person can feel highly elevated and high energy and have racing thoughts, juxtaposed with depressive episodes, where a person feels down,

slow, and unable to do simple things. Sometimes, people in manic or depressive episodes may exhibit psychosis as a symptom (NIMH, 2024a).

The MDPS estimated prevalence of past-year schizophrenia spectrum disorders to be 1.2% and lifetime prevalence to be 1.8%. The past-year prevalence of bipolar disorder was estimated to be 1.5% (Ringeisen et al., 2023). Current understanding is that although 1.5–3.5% of people will meet diagnostic criteria for a psychotic disorder, a significantly larger variable number will experience at least one psychotic symptom in their lifetime (Calabrese and Al Khalili, 2025).

VHA estimated 127,445 cases of schizophrenia among its enrollees in 2017, equaling approximately 2.1% of the VHA-treated population (VA, 2018). An earlier analysis of VHA EHRs identified 163,859 patients (3.7%) with either bipolar disorder or schizophrenia (Trivedi et al., 2015). A meta-analysis of studies of veterans with a mean study participant age of 65+ found 11.2% pooled prevalence for schizophrenia, though the authors note the estimate may have been skewed by including two studies with very high prevalence owing to higher rates of more severe cases enrolling in VHA inpatient mental health care (Williamson et al., 2018). The same study estimated a pooled prevalence of bipolar disorder to be 3.9% (Williamson et al., 2018).

Analysis Results

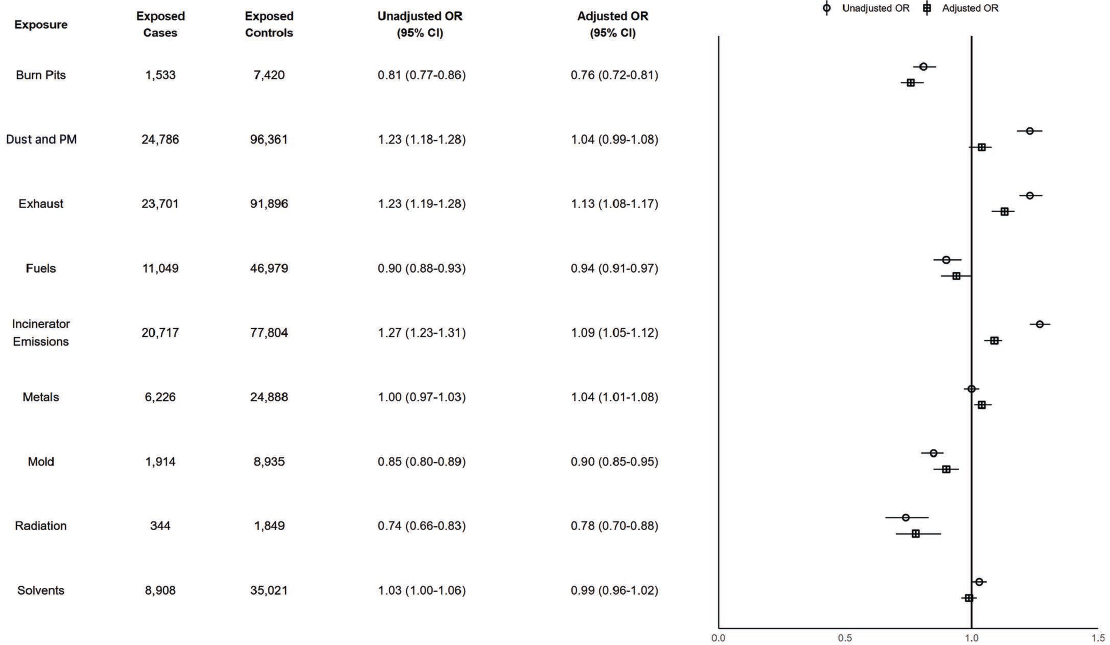

There were 29,097 cases (2.5%) of a composite outcomes of psychosis/schizophrenia and 40,498 cases (3.5%) of bipolar disorder. Figure 6-6 shows that exposure to exhaust is associated with a risk-conferring relationship with psychosis and schizophrenia with an adjusted OR of 1.13 (95% CI: 1.08–1.17). All exposures had no differences in the magnitude of association when stratifying by TBI, which suggests no interaction between these exposures and TBI on odds of psychosis and schizophrenia.

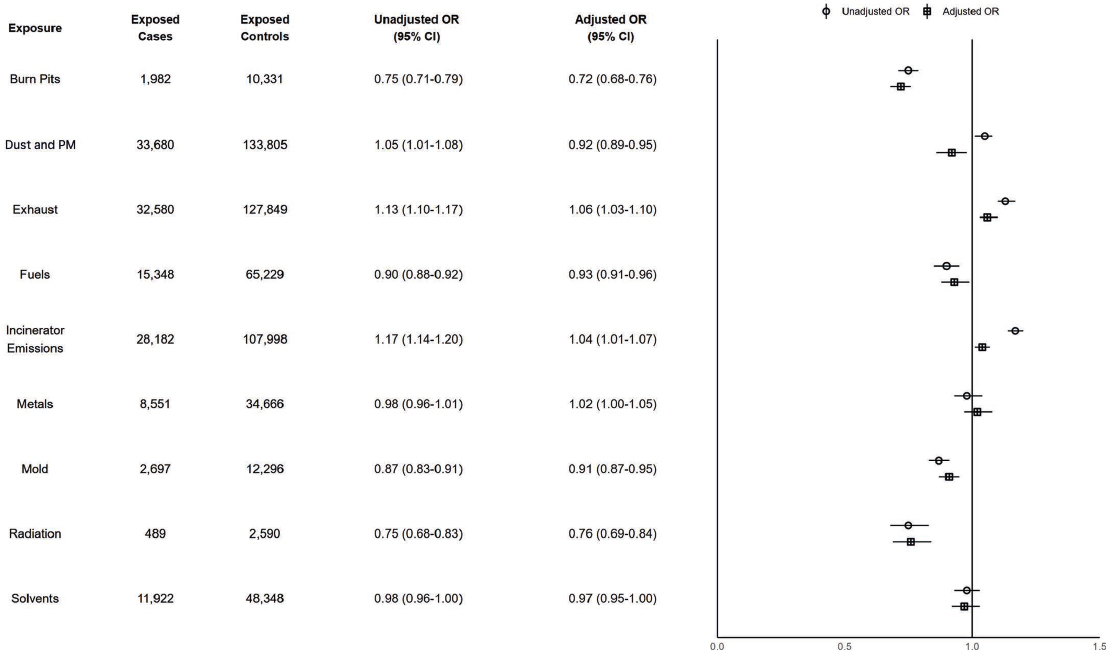

In Figure 6-7, none of the adjusted ORs and associated CIs for the exposures and bipolar disorder met the prioritization criteria for additional discussion. There were no differences in the magnitude of association when stratifying by TBI, which suggests no interaction between these exposures and TBI on odds of bipolar disorder.

Literature Search Results

PM and SMI

The literature search yielded 16 studies on SMI, none of which were specific to military or veteran populations. Investigated components of air pollution include PM2.5, PM10, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, carbon

NOTES: Exposed cases n = 29,097; exposed controls n = 116,364. CI = confidence interval; ILER = Individual Longitudinal Exposure Record; OR = odds ratio; PM = particulate matter.

NOTES: Exposed cases n = 40,498; exposed controls n = 161,961. CI = confidence interval; ILER = Individual Longitudinal Exposure Record; OR = odds ratio; PM = particulate matter.

monoxide, black carbon, and ozone. Overall, there was generally evidence of an association between air pollutants and at least one SMI outcome.

One study used a Bayesian spatial model to estimate the association between air pollution, defined as annual mean concentration of PM2.5, and prevalence of SMI (including schizophrenia, psychosis, and bipolar disorder in one measure) in England, finding greater national-level prevalence of SMI was significantly associated with air pollution (Cruz et al., 2022). However, a cohort study that pooled data from six European countries found a positive but not significant association between long-term exposure to PM2.5 and mortality from psychiatric disorders, which the authors defined as a broad range of ICD-9- and ICD-10-coded mental and behavioral disorders, including SMI (Andersen et al., 2022). The authors found long-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide and black carbon were positively associated with psychiatric disorder mortality; ozone was negatively associated with mortality, but this association attenuated and was no longer significant after adjusting for other pollutants.

Eight studies considered the relationship between schizophrenia and PM2.5, PM10, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and/or carbon monoxide, including a meta-analysis of 13 studies (Song et al., 2023) and a systematic review (Braithwaite et al., 2019). Seven of these studies assessed PM2.5 and all reported a positive association between exposure to PM2.5 and schizophrenia (or schizophrenia-related hospitalizations); this result held across the meta-analysis and other types of studies (Chen et al., 2023; Nobile et al., 2023; Pignon et al., 2022; Qiu et al., 2022; Qiu et al., 2023; Song et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2024). Song and colleagues (2023) found a small but significant association with short-term exposure to PM2.5, with a peak at lag day 5 and a stronger association in people under age 45, though they note high heterogeneity among the studies included in the meta-analysis. A large longitudinal cohort study in Italy found long-term PM2.5 significantly associated with incident schizophrenia, though the magnitude of effect was also small (Nobile et al., 2023). The two studies by Qiu and colleagues (2022, 2023) also found higher risk of schizophrenia hospitalizations associated with increased exposure in the United States, including in a population restricted to those aged 65 and older (Qiu et al., 2022), and of hospitalizations for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in people over age 30 and in areas with higher community poverty (Qiu et al., 2023). Similarly, an ecological study of wildfire-specific PM2.5 and emergency department visits in California found wildfire smoke events significantly increased risk of emergency department visits for schizophrenia (Chen et al., 2023). The study by Pignon and colleagues (2022) found the association between PM2.5 exposure and schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders-related emergency department visits in France was significant only in multivariable analysis. Finally, Zhu and colleagues (2024) completed a two-sample Mendelian

randomization study and found genetically predicted PM2.5 exposure significantly increased risk of schizophrenia; multivariate analysis confirmed this effect of PM2.5 was independent of other air pollutants.

All three studies that assessed PM10 found a positive association with schizophrenia (Braithwaite et al., 2019; Pignon et al., 2022; Song et al., 2023), though there is less evidence than for PM2.5. For example, the systematic review by Braithwaite and colleagues (2019) only found one study relevant to schizophrenia (which reported a significant positive association between PM10 and schizophrenia-related hospitalizations). Song and colleagues (2023) again reported a small but significant increased risk (and also found the same results for PM with diameter between 2.5 and 10 micrometers); this association was again stronger in younger people. As with their results for PM2.5, the Pignon and colleagues (2022) study found the association between PM10 exposure and schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders-related emergency department visits significant only in multivariable analysis.

Increased exposure to nitrogen dioxide was consistently positively associated with risk of schizophrenia, especially among women (Song et al., 2023), or risk of hospitalization for schizophrenia or schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (Qiu et al., 2022, 2023). The 2023 Qiu and colleagues paper also found this result was more pronounced among male study participants and people living in communities with higher poverty. In their meta-analysis, Song and colleagues (2023) also found a small but significant association between increased sulfur dioxide and risk of schizophrenia, particularly among women, but null results for carbon monoxide.

Four studies considered components of air pollution and psychosis (Bakolis et al., 2021; Braithwaite et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2022; Nguyen et al., 2021). Braithwaite and colleagues (2019) did not identify any studies on psychosis. Two studies on PM2.5 had conflicting findings: a case-crossover study in South Korea found a small but significant increased risk of psychosis-related emergency department visits associated with short-term PM2.5 exposure (Lee et al., 2022), while a time-series analysis of California data did not find an association (though the authors did find same-day PM2.5 was associated with increased risk of emergency department visits for all mental health outcomes combined) (Nguyen et al., 2021). Two results for PM10 were consistent. A cross-sectional analysis in London found a positive association between exposure to PM10 and psychotic experiences (Bakolis et al., 2021); Lee and colleagues (2022) again found a small but significant increased risk of psychosis-related emergency department visits associated with short-term PM10 exposure. These authors also found significant associations between short-term nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide and psychosis-related emergency department visits, and null results for carbon monoxide and ozone (Lee et al., 2022). The time-series analysis

also did not find a significant result for ozone (Nguyen et al., 2021), but the cross-sectional analysis in London reported a significant negative association between ozone and psychotic experiences (Bakolis et al., 2021).

Ten studies assessed the relationship between air pollutant components and bipolar disorder. However, Braithwaite and colleagues (2019) did not find any relevant studies on PM2.5 or PM10 and the outcome.

The eight studies that assessed PM2.5 found positive or null results. Both a prospective cohort study (Li et al., 2023) and a cross-sectional study (Hao et al., 2022) that used UK Biobank data found an increase in PM2.5 significantly increased risk of bipolar disorder incidence and symptoms. Li and colleagues (2023) also found consistent associations for all studied pollution components (PM2.5, PM10, nitrogen dioxide, nitrogen oxides) in high and intermediate genetic risk groups. The Qiu and colleagues (2022) case-crossover study also found a significant positive association between PM2.5 and bipolar disorder hospitalization rate among people age 65 or older. However, most studies failed to find an association between PM2.5 and bipolar disorder. The large longitudinal cohort in Italy did not find an association between long-term PM2.5 exposure and incident bipolar disorder (Nobile et al., 2023); the studies by Pignon and colleagues (2022) and Nguyen and colleagues (2021) found no association with emergency department visits related to bipolar disorder (though Nguyen and colleagues [2021] did find same-day PM2.5 was associated with increased risk of emergency department visits for all mental health outcomes combined); the ecological study of wildfire-related PM2.5 found nonsignificant results for a composite mood disorder outcome including depression and bipolar disorders (Chen et al., 2023); and the two-sample Mendelian randomization study did not find a causal effect of genetically predicted PM2.5 exposure (Zhu et al., 2024).

Of those that assessed PM10, one study found a positive association and one found no association. The Li and colleagues (2023) cohort study found the risk of bipolar disorder was positively associated with long-term PM10 exposure, but the Pignon and colleagues (2022) study did not find an association. Additionally, a cross-sectional study in Italy found short-term exposure to PM10 was associated with a change in bipolar disorder presentation, with a reduction in mania rating (symptoms moved toward the depressive end) and a higher risk of manic episodes with mixed4 features (Carugno et al., 2021).

A few studies examined other specific air pollutants. While the Italian longitudinal cohort study did not find an association between long-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide and bipolar disorder (Nobile et al., 2023),

___________________

4 Mixed episodes of bipolar disorder include both depressive and manic symptoms (NIMH, 2024a).

another prospective cohort study did find an increased risk of the disorder, along with an association with nitrogen oxides (Li et al., 2023). The time-series analysis of California data found increased ozone increased risk of emergency department visits for bipolar disorder, especially in the warmer months (Nguyen et al., 2021).

Metals and SMI

One cohort study that pooled data from six European countries found no association between long-term exposure to seven metal and metalloid components of PM2.5 (copper, iron, nickel, potassium, silicon, vanadium, and zinc) and mortality from psychiatric disorders, which the authors defined as a broad range of ICD-9- and ICD-10-coded mental and behavioral disorders, including SMI (Andersen et al., 2022).

Three studies assessed the relationship between metal concentrations in biologic samples and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, none of which were specific to military or veteran populations (Arain et al., 2015; Baj et al., 2020; Laidlaw et al., 2018). Studies assessed specific metals in hair or serum samples. A systematic review of serum metal levels and diagnosed schizophrenia found levels of phosphorus were generally lower in people with schizophrenia, while levels of antimony, chromium, lead, nickel, and uranium were generally higher (Baj et al., 2020). The authors found mixed results for serum levels of aluminum, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, selenium, and zinc. However, a small (n = 222) cross-sectional study using hair samples from men with bipolar disorder, men with schizophrenia, and controls found levels of both aluminum and manganese were significantly higher in men with either psychiatric disorder than controls (Arain et al., 2015). Another cross-sectional study of 67 patients with schizophrenia found mixed results for the correlation of levels of various metals in hair and schizophrenia symptoms; for example, cobalt, copper, and lead were negatively correlated with negative symptoms of schizophrenia (e.g., blunt affect and emotional withdrawal), while lead was positively associated with resistance symptoms (e.g., hostility, suspiciousness) (Laidlaw et al., 2018).

Radiation and SMI

A systematic review and meta-analysis of low-to-moderate exposure to ionizing radiation on mortality from a heterogeneous composite measure of mental and behavioral disorders, which included schizophrenia, found significantly lower mortality from such disorders among the exposed populations compared to the general population (Lopes et al., 2022). The authors note this result may be explained by the healthy worker effect.

Burn Pits, Fuels, Mold, or Solvents and SMI

The committee’s search yielded zero results on the possible relationships between exposure to burn pits, fuels, mold, or solvents and the risk of SMI.

Conclusions

Conclusion 6-6: Based on its analysis of the available data, the committee finds there is a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to exhaust and a composite outcome measure of schizophrenia and psychosis. The committee does not find a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, dust and particulate matter (PM), fuels, incinerator emissions, metals, mold, radiation, or solvents and this outcome.

Based on the literature review, there is suggestive evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to PM and schizophrenia and psychosis. There is mixed evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to metals and schizophrenia. There is inadequate and insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to radiation and schizophrenia. There is no identified literature on the relationship between exposure to burn pits, fuels, mold, or solvents and schizophrenia and psychosis. There is also no identified literature on the relationship between exposure to metals or radiation and psychosis.

Synthesizing the committee’s data analysis and literature review, the committee concludes there is a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to exhaust or PM and schizophrenia and psychosis. The committee further concludes there is inadequate or insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, dust, fuels, incinerator emissions, metals, mold, radiation, or solvents and a composite outcome of schizophrenia and psychosis.

Conclusion 6-7: Based on its analysis of the available data, the committee does not find a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, dust and particulate matter (PM), exhaust, fuels, incinerator emissions, metals, mold, radiation, or solvents and bipolar disorder.

Based on the literature review, there is mixed evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to PM and bipolar disorder. There is insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to metals and bipolar disorder. There is no identified literature on the relationship between exposure to burn pits, fuels, mold, radiation, or solvents and bipolar disorder.

Synthesizing the committee’s data analysis and literature review, the committee concludes there is inadequate or insufficient evidence of a possible risk-conferring relationship between exposure to burn pits, dust and PM, exhaust, fuels, incinerator emissions, metals, mold, radiation, or solvents and bipolar disorder.

SLEEP DISORDERS

Sleep disorders are common and may arise from physical or mental health conditions. They include abnormalities of sleep, such as insomnia and hypersomnia, and parasomnias, which are abnormal behaviors or phenomena occurring before, during, after, or in between periods of sleep. Examples of other sleep disorders include restless legs, narcolepsy, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) (Karna et al., 2023). Insomnia is a chronic disorder where individuals struggle to fall asleep, stay asleep, or get high-quality restful sleep. Chronic insomnia occurs three or more times per week, lasts 3 months or longer, and cannot be explained by other health problems (NHLBI, 2022). OSA is a common chronic sleep disorder in which the airway becomes obstructed during sleep, usually because the upper airway and tongue have collapsed while sleeping. This prevents the body from receiving the proper amount of oxygen, can cause snoring or gasping, and reduces the quality and length of sleep (NHLBI, 2025; Rowley et al., 2024). Consequences of undiagnosed or untreated sleep disorders, and resultant disturbed sleep quality or duration, can be severe, including increased rates of heart attacks, strokes, motor vehicle accidents, and cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease (Bubu et al., 2016; Daghlas et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2024; NHLBI, 2025; Pocobelli et al., 2021; Rowley et al., 2024).

Sleep disorders are common in the general population. Among U.S. adults aged 18+, NHIS reports that 14.5% reported trouble falling asleep most or every day in the last 30 days (Adjaye-Gbewonyo et al., 2022). In one study on the prevalence of insomnia, roughly one-third of adults report at least one nocturnal insomnia symptom across population-based studies (Morin and Jarrin, 2013). A review of studies on OSA found a mean prevalence of 22% in men and 17% in women (Franklin and Lindberg, 2015).

Insomnia and other sleep disorders are also common among veterans. A study of post-9/11 veterans enrolling in VHA found that 57.2% screened

positive for insomnia disorder at entry into VHA care (Colvonen et al., 2020). Another study of VHA EHRs found that 11.8% of veterans receiving outpatient care at VA medical facilities in 2018 had insomnia and 22.2% had sleep-related breathing disorders (Folmer et al., 2020). A serial cross-sectional study of veterans seeking care in the VHA system between 2000 and 2010 found a prevalence of 26% for insomnia and 47% for sleep apneas (Alexander et al., 2016).

Analysis Results

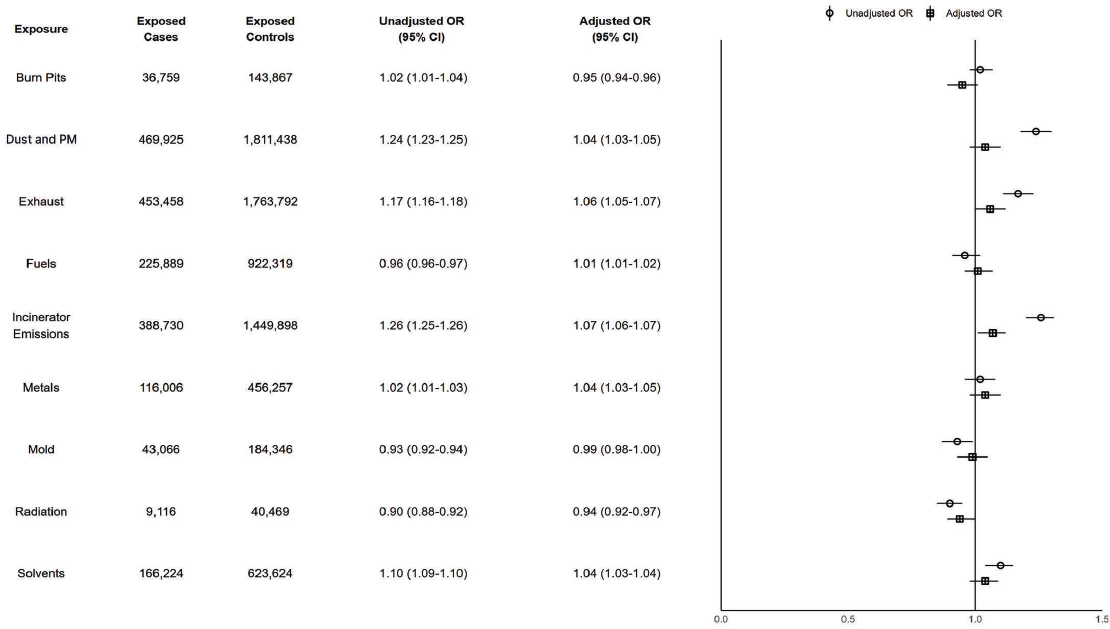

There were 572,012 cases (49.9%) of sleep disorders. None of the adjusted ORs and associated CIs for any exposure of interest and sleep disorders met the prioritization criteria for additional discussion (see Figure 6-8). Among people with TBI, the association between exposure to burn pits and sleep disorders is 17.0% higher than among people who did not have TBI.

Literature Search Results

Burn Pits and Sleep Disorders

One small study (n = 100) assessed burn pit exposure and OSA in previously deployed military personnel (Powell et al., 2021). In a subset of participants from a larger prospective study of military personnel with chronic dyspnea after deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan, prevalence of OSA was similarly high but not significantly different in those with self-reported burn pit exposure and those without. Some measures of breathing disruptions, sleep fragmentation, and sleep architecture were significantly worse in the unexposed group, and other sleep variables were not significantly different between those reporting exposure to burn pits and those without the exposure. There were also no significant differences in subgroup analyses of those with higher levels of exposure (self-reported burn pit duty and extended hours of exposure) compared to those with no exposure. The authors note the study was constrained by confounding comorbidities (smoking status, diabetes, and obesity).

PM and Sleep Disorders

Seven studies examined the relationship between PM and sleep outcomes, including one meta-analysis (Zhao et al., 2024b), three other systematic reviews (Clark et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Wallace et al., 2023), and three cohort studies (Andersen et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2023). None were specific to military or veteran populations.

NOTES: Exposed cases n = 572,012; exposed controls n = 2,286,793. CI = confidence interval; ILER = Individual Longitudinal Exposure Record; OR = odds ratio; PM = particulate matter.

The studies investigated air pollution overall, PM2.5, PM10, and specific air pollutants.

A systematic review stated general support for an association between ambient air pollution and disrupted sleep and between PM, nitrogen dioxide, and poor sleep quality (Wallace et al., 2023). Similarly, a systematic review of 22 studies found some evidence of an association between air pollution overall and poor sleep quality, including sleep-disordered breathing, shorter sleep duration, and sleep disturbances (Liu et al., 2020). Additionally, another systematic review of five studies concluded there is a suggested association between traffic-related air pollution and OSA but noted inconsistent results for the duration of exposure to PM2.5, PM10, and nitrogen dioxide, as they vary by season, temperature, and location, and heterogeneity in exposure measurement across included studies (Clark et al., 2020).