The Role of Seafood Consumption in Child Growth and Development (2024)

Chapter: Summary

Summary

BACKGROUND

Seafood, including marine and freshwater fish, mollusks, and crustaceans, is a protein food that is also a rich source of the nutrients needed in pregnancy and lactation as well as those vital to support growth and development from infancy through adolescence. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025 (DGA) includes an overarching recommendation that all U.S. adults aim to consume at least 8 ounces (two servings) of seafood per week.1 For children, the DGA recommends two servings per week in amounts corresponding to an individual’s total daily caloric intake. The DGA also includes a recommendation to introduce seafood to children when they are around 6 months of age.

Although seafood is an important source of key nutrients, it can also be a source of exposure to contaminants such as methylmercury, persistent pollutants including per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls, and microbiological hazards that may be detrimental to the growth and development of children. The Closer to Zero action plan, launched by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2021, proposed an approach to reduce exposure through food, including seafood, to four metals—arsenic, lead, cadmium, and mercury—that can have adverse effects on child development, particularly neurodevelopment, with the goal of reducing blood-level concentrations of these contaminants in infants and children by decreasing exposure from foods that contain them. The recommendations in the action plan serve as a foundation for DGA recommendations about consuming seafood.

The juxtaposition of nutritional benefits and toxicological risks associated with the consumption of seafood led FDA, in collaboration with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to ask the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) to convene a committee to review the role of seafood in the diets of pregnant and lactating women and children, including adolescents—with consideration of the components found in seafood that are potentially detrimental as well as those that are beneficial—to evaluate their respective, interacting, and complex roles in child development and lifelong health. Additionally, these federal sponsoring agencies asked the committee to evaluate when or when not to conduct a formal risk–benefit analysis (RBA) relative to risk–benefit factors including how to assess the quality and uncertainty of an RBA

___________________

1 Throughout the report, seafood consumption guidelines refer to the recommendations in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. This clarification was added after release of the report to the study sponsor.

and to provide scientific information and principles that can serve as a foundation to evaluate confidence in the potential conclusions of an RBA. The committee was further asked to identify and comment on additional context, including equity, diversity, inclusion, and access to health care, that may be additive to the findings of an RBA approach to the task.

The committee approached its task by evaluating evidence submitted by the study sponsors, supplemented with additional searches of existing databases and published literature. The committee contracted with the Texas A&M University Agriculture, Food, and Nutrition Evidence Center to conduct an update of two systematic reviews from the USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review—one on seafood consumption during childhood and adolescence and neurocognitive development and the other on seafood consumption during pregnancy and lactation and neurocognitive development in the child. In addition, the committee requested the Evidence Center conduct a de novo systematic review on toxicants in seafood and neurocognitive development in children and adolescents. The committee also commissioned two scientists from the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future at the Bloomberg School of Public Health to perform analyses using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) cross-sectional data on seafood consumption and factors that affect decision making and dietary patterns. To provide deeper context for both nutrient intake and exposure to contaminants, particularly among at-risk groups, the committee’s review of evidence included the assessment of data from the United States and from Canadian populations, including Native and Indigenous peoples. While this evidence was considered, the committee’s recommendations apply only to U.S. populations.

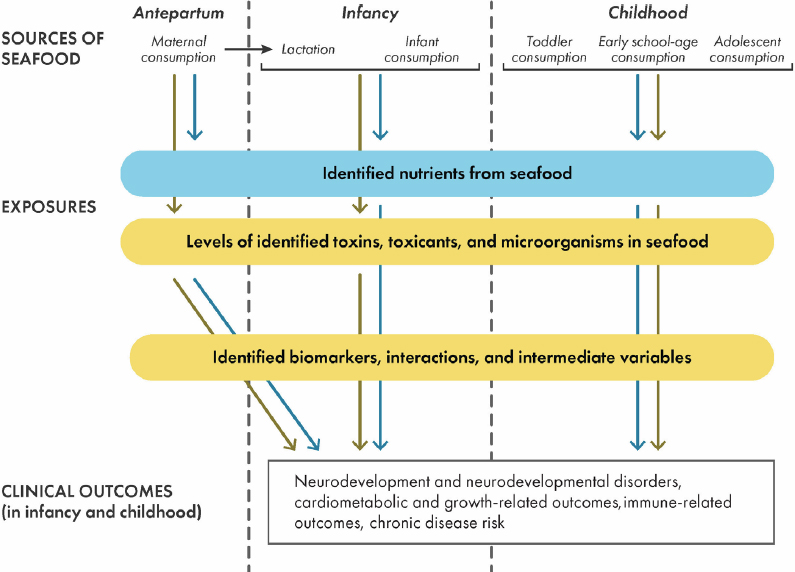

As part of its task, the committee was asked to develop and implement an approach to integrating scientific evidence in a transparent way and draw conclusions on questions related to seafood and child development outcomes. To facilitate this, the committee developed a conceptual framework (Figure S-1). The conceptual framework indicates the relationships of sources of nutrient, contaminant, and micro-organism exposures in seafood with health outcomes. The framework also identifies relevant time periods over the life course of the population groups of interest. The framework was used to guide the committee’s discussions, particularly on exposure and health outcomes through consumption of seafood by these population groups.

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH CONSUMING SEAFOOD

Types and Amounts of Seafood Consumed

According to dietary intake data from 2018–2019, the 10 most consumed seafood species for the total U.S. population accounted for about three-quarters of the total seafood consumption. All of the 10 most consumed species in both the United States and Canada are rich in protein. Several of them, such as salmon and albacore tuna, are also rich in docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), which are n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs). The remaining most consumed seafood species are lower in total lipids, including n-3 LCPUFAs.

During the past century, overall consumption of seafood has increased and is attributable to a combination of increasing population and greater per capita consumption. Most of the increase has been in the consumption of fresh and frozen seafood, as consumption of canned seafood has remained generally stable and cured seafood (e.g., fermented, pickled, or smoked) has had a negligible contribution to overall seafood consumption. Most seafood consumed in the United States is imported.

Most of the seafood consumed by women of childbearing age and children comes from retail purchases (e.g., supermarket, grocery store, or convenience store) and is consumed at home as part of lunch or dinner meals and, less frequently, as restaurant meals. School and other institutional meals provide a negligible contribution to overall seafood intake.

Factors Influencing the Choice to Consume Seafood

Factors, including cultural background, income, and geographic locations, influence the types and amounts of seafood consumed. Native and Indigenous peoples and recreational fishers are likely to consume seafood more frequently than other groups. Individuals with lower household incomes may tend to eat fish less frequently and consume fish that are less rich in n-3 LCPUFAs. With regard to the types of seafood, individuals identifying as non-Hispanic Asian and non-Hispanic Black most commonly consume shrimp, salmon, other fish, and other unknown fish or catfish, whereas those who identify as Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and those of other racial and ethnic identities consume more shrimp, tuna, salmon, and crab.

Residence in a geographic area near the Atlantic, Pacific, or Gulf of Mexico coasts, or the Great Lakes, is associated with greater average seafood consumption, although few children or women in these areas consume the recommended two servings of seafood per week.

Limited information is available regarding the awareness of fish consumption guidelines for women of childbearing age and children. Longitudinal data from over a decade ago suggest that there was consumer awareness about prior guidelines. However, consumer awareness was not a factor in amounts of seafood consumed.

Nutrient Intake from Seafood Consumption

Seafood is a source of protein that is high in biological value (i.e., contains all the essential amino acids and has high absorption rates); therefore, the DGA includes seafood as a subgroup of dietary protein that also includes the subgroup of meat, poultry, and eggs.2 Some types of seafood contain EPA and DHA, which are necessary for fetal development as they form key components of cell membranes; they are also precursors of several metabolites that are potential lipid mediators. Although EPA and DHA can be synthesized from alpha-linolenic acid (an essential short-chain n-3 fatty acid), the conversion rate is less than 10 percent in humans.

NHANES data for adults indicate that, compared with women 25 years of age or older, younger women consume lower amounts of micronutrients from seafood, except for vitamin B12. No large differences in the average intakes of any nutrients were observed by racial and ethnic identity. Higher income is associated with higher intake

___________________

2 Available at https://health.gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/dietary-guidelines/previous-dietary-guidelines/2015/advisory-report/appendix-e-3/appendix-e-31a1 (accessed February 13, 2024).

from seafood for all nutrients, except vitamin D, which was the same in women from middle- and high-income households. Differences in nutrient intake between seafood consumers and nonconsumers are small.

NHANES data for children indicate that a small proportion of daily protein intake is from seafood and that average protein intake from seafood high in n-3 LCPUFA is less than 2 grams per day. Those in the highest percentile of protein intake from seafood that is also high in n-3 LCPUFAs consume only about 27 grams of protein per day, which contributes approximately 25 percent of their daily total protein intake. Boys showed a higher protein intake from seafood compared with girls; however, the proportion of total protein intake from seafood was below 25 percent in all age groups. Non-Hispanic Asian children had higher intakes of n-3 LCPUFAs compared with all other children, and Hispanic children had the second-highest intakes of n-3 LCPUFAs.

Primary Findings and Conclusions

Findings

- Despite population-level increases in seafood disappearance during the past decade, seafood consumption among women of childbearing age and children and adolescents is generally low and has remained similar to that reported in Seafood Choices: Balancing Benefits and Risks (IOM, 2007).

- Limited evidence is available to suggest that the public is knowledgeable about both the types and amounts of seafood that are recommended for consumption by women of childbearing age and children and adolescents.

- Most of the seafood consumed by both women of childbearing age and children and adolescents comes from retail purchases and is consumed at home as part of lunch or dinner meals. School lunch is a negligible contributor of seafood to children’s diets.

- Limited evidence is available on the types and preparation methods of seafood consumed by pregnant and lactating women and children and adolescents in the general population.

- Although few women of childbearing age and children and adolescents in the general population meet the recommended intake of two servings of seafood per week, some from certain ethnic or cultural backgrounds—such as those of Asian or Native American heritage, Indigenous peoples, and sport and subsistence fishers and their families—consume greater than average amounts of seafood.

- Multiple factors influence patterns of seafood consumption, including residence in coastal areas or near bodies of water such as the Great Lakes, familiarity with fish preparation methods, and cultural and traditional practices.

- Current evidence on the nutrient content of seafood indicates that seafood is a rich source of multiple nutrients, including vitamin D, calcium, potassium, and iron, which are identified as nutrients of public health concern by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and play roles in supporting pregnancy and lactation as well as growth and development.

- Seafood is an important source of n-3 LCPUFAs, which are key nutrients for the prenatal period, during lactation, and throughout childhood. Choline, iodine, and magnesium are additional nutrients that are provided by seafood and have important functions throughout childhood and adolescence.

- Individuals who do not consume seafood likely have intakes of n-3 LCPUFAs below recommended amounts.

- Seafood is one component of healthful dietary patterns described in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The majority of the U.S. and Canadian population has lower-than-recommended intakes of n-3 LCPUFAs from seafood. Intakes are highest among high-income women and children, but income status, however, is not consistently associated with intake levels of other nutrients.

- Among Native and Indigenous populations who are transitioning away from traditional diets, limiting seafood consumption increases the risk of not achieving optimal intake of a range of nutrients, including n-3 LCPUFAs. Low seafood consumption may also contribute to inadequate nutrient intakes among other at-risk populations who are low consumers, such as non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic Americans, and especially among those with lower incomes or experiencing food insecurity.

Conclusions

- Most women of childbearing age and children and adolescents do not consume the recommended amounts and types of seafood. Strategies to support increasing consumption toward meeting recommendations are needed.

- Identification of strategies to overcome barriers to seafood consumption are needed so (1) individuals who consume some seafood will increase their intake toward recommended amounts, and (2) nonconsumers will begin consuming seafood with the goal of meeting recommended amounts.

- Insufficient evidence exists to suggest a need to revise seafood consumption guidelines, but a need does exist to identify strategies to help individuals meet current guidelines.

- Taken together, the committee concludes that nutrient intakes from seafood by women of childbearing age and children are low.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 1: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should identify strategies to address gaps in the current National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey monitoring to better assess the sources, types, amounts, and preparation methods of seafood consumed by women of childbearing age, pregnant and lactating women, and children and adolescents up to 18 years of age.

Recommendation 2: The U.S. Department of Agriculture should reevaluate its federal nutrition programs, especially school meals, to support greater inclusion of seafood in meal patterns.

RESEARCH GAPS

- Research is needed to characterize the knowledge of, and responses to, current seafood consumption guidelines among women of childbearing age and children and adolescents. This should include research of seafood consumption by children, particularly in school settings and other meals consumed outside the home.

- Further research is needed to assess the types, amounts, and patterns of seafood consumed during pregnancy and lactation.

- Additional research is needed to assess the barriers to providing seafood as a component of meals served in schools and other settings frequented by children.

- Data are needed on levels of nutrient intake by seafood consumers who meet current seafood intake recommendations compared to nonconsumers and low consumers of seafood.

- Additional data are needed on the nutrient composition of types of seafood frequently consumed in different geographic regions in the United States and Canada.

HEALTH OUTCOMES ASSOCIATED WITH EXPOSURE TO CONTAMINANTS IN SEAFOOD

Exposure to Contaminants in Seafood

Estimates of exposure to contaminants of concern through consumption of seafood depend principally on two factors: the amount of seafood consumed and the amount of the contaminant in seafood. Using the reported consumption rates from national surveys such as NHANES and the Canadian Community Health Survey, it is possible to quantitatively estimate the exposure of different contaminants from seafood consumption among women of childbearing age, children, and adolescents. The concentration of contaminants in seafood depends on many factors including the species, age of the fish, its geographic origin, how it is prepared, and which part of the fish is consumed.

Seafood can contain a broad range of contaminants, including microbial contaminants. Concentrations of contaminants such as metals, metalloids, and other trace elements along with organic compounds such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) vary widely among species and geographic region, by the size and age of the organism, and according to whether they are wild caught or cultivated, among other factors. Mercury is the most studied contaminant in seafood, but because seafood consumption is generally below recommendations and the concentrations of mercury for commonly consumed seafood (except for tuna) tend to be relatively low, exposure will likely not exceed guideline values for most people. Certain subgroups of the population, including Native and Indigenous peoples and subsistence or sport fishers could be at greater risk from exposure to seafood toxicants because of their pattern of seafood intake or source of seafood.

Exposures to pathogens and microbial toxins occur episodically as “outbreaks” at a specific time and location, or as food poisoning cases among individuals who consume contaminated seafoods. These risks are often mitigated by the closing of the harvest at specific times or locations or by removing contaminated seafood from the market before it is sold.

FDA oversees the inspection of both domestic and imported seafood to ensure its safety to consumers. Products are assessed for various adulterations including the presence of contaminants and pathogens as well as mislabeling and unsanitary manufacturing, processing, or packing. An Institute of Medicine (IOM) report indicates that most of the seafood sold in the United States is wholesome and unlikely to cause illness. Potential differences in contaminants and pathogens from imported and domestic products are difficult to assess owing to the great variety of seafood products and processing methods.

Biomarkers of Exposure to Toxicants Associated with Seafood Consumption

Epidemiological studies relating seafood intake during pregnancy to biomarkers of contaminant exposure have largely focused on mercury, with findings of higher blood, hair, and toenail mercury concentrations among those who consumed more seafood. Evidence from NHANES indicates that higher seafood intake is positively correlated with blood levels of mercury and urinary concentrations of total arsenic, domoic acid, and arsenobetaine, among both women of childbearing age and children. Studies of the biomarker concentrations of other contaminants associated with seafood consumption are relatively scarce, and for all contaminants very little data exist on biomarker associations with seafood intake specifically during lactation, infancy, and childhood.

Health Outcomes

Higher fish consumption by women of childbearing age, including women who are pregnant and lactating, and by children is either generally associated with a lower risk of adverse health outcomes or no association with health outcomes is found. An exception is higher exposures among certain population subgroups such as consumers of sport-caught species or groups dependent on subsistence fishing. Moreover, there is evidence that greater fish consumption by women during pregnancy is likely associated with several health benefits, including improved birth outcomes. Taken as a whole, the evidence reviewed by the committee indicates that higher fish consumption is associated with lower risk of adverse health outcomes or no association with health outcomes. The evidence for increased risk of adverse health outcomes associated with seafood consumption was insufficient to draw a conclusion.

Mechanisms of Action

Some experimental evidence supports that the toxicity of mercury and PCBs can be modified by other factors (i.e., in antioxidant response pathways). This literature is complex, and the committee was not able to identify supportive evidence in humans.

Primary Findings and Conclusions

Findings on Contaminants of Concern and Exposure Through Seafood

- Toxins, toxicants, and microbes, including persistent bioaccumulative chemicals, metals and metalloids, infectious organisms, microplastics, and micro-organisms, may be present in seafood at levels hazardous to consumers. The concentration of these various contaminants in seafood depends on many factors, including species, trophic position, size, age, geographic location, and origin—wild caught or farm raised.

- With the exception of some types of tuna, the most commonly consumed seafood species in the United States and Canada contain relatively low concentrations of methylmercury, and concentrations of other metals and metalloids tend to be limited to certain species and geographic areas.3

- Among adults and children, seafood consumption is associated with higher blood, hair, and toenail levels of mercury, and urinary concentrations of certain forms of arsenic, particularly those common to seafood such as arsenobetaine.

- Average intake levels of methylmercury from seafood are below the FDA “Closer to Zero” recommended limits among women of childbearing age, infants, and children, except for those who frequently consume tuna.4

- PCBs and mercury are the key drivers for fish consumption advisories and PCBs are particularly relevant in the Great Lakes region.

- Certain population groups, in particular Native Americans and Indigenous peoples, as well as subsistence and sport fishers and their families, may consume more seafood species or seafood components from geographic locations that could have high concentrations of mercury and PCBs than individuals in the general population, thereby exceeding recommended limits.5

Findings on Health Outcomes

- Many of the studies reviewed by the committee reported outcomes correlated with seafood consumption generally and without differentiation as to species. One commonly accepted assumption has been that omega-3 long-chain fatty acids in seafood, particularly DHA, contribute benefits, possibly in combination with other nutrients.

- The evidence reviewed indicates that some gains in neurodevelopment may be achieved during childhood and are apparent in the children of women who consume greater quantities of seafood during pregnancy compared to those who consume lower quantities or no seafood.

- Seafood consumption by women during pregnancy may also have a protective effect against adverse neurocognitive outcomes in their children that is linked to the nutrients in seafood, particularly the n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids that are essential to brain development. Associations of health outcomes with seafood intake differ between the general populations and recreational and subsistence fishers.

Conclusions

- The committee found insufficient evidence to assess exposure to most consumers associated with emerging contaminants in seafood, including PFAS, microplastics, and domoic acids.

- PBDE exposure is not due primarily to seafood consumption; however, as PBDEs migrate into aquatic environments, risk of increased exposure through seafood may emerge.

- Although seafood consumption is generally low across population groups, it continues to be an important predictor of methylmercury, arsenic, and PCB exposure and may be important for assessing PFAS exposure,

___________________

3 The sentence was revised after release of the report to the study sponsor to clarify that concentrations of methylmercury vary in different types of tuna after release of the report to the study sponsor.

4 This sentence was modified after release of the report to the study sponsor to clarify that recommended limits of contaminant exposure are based on the Closer to Zero Action Plan.

5 This section was modified after release of the report to the sponsor to reference recommended limits rather than acceptable risk levels.

- The results of the studies identified through the committee’s evidence reviews did not support a beneficial association of seafood consumption during childhood and adolescence and reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.

- No evidence was identified to determine whether seafood consumption among children or adolescents is associated with benefits to reducing risk of other diseases such as immune disease.

- The evidence reviewed on health outcomes associated with seafood consumption for women of childbearing age, children, and adolescents is not adequate to support an accurate assessment of the health benefits and risks associated with meeting the recommended intakes of seafood for this population group.

where evidence is beginning to emerge. Therefore, if fish intake were to increase to DGA-recommended levels, then exposures would likely increase.

Research Gaps

- Additional research is needed to assess geographic and temporal trend data for levels of methylmercury, mercury, and other contaminants in seafood, and to monitor intake levels of these contaminants among women of childbearing age, infants, and children. Special attention should be given to at-risk population groups such as Native Americans and Indigenous peoples, and to other at-risk groups, such as subsistence and sport fishers and their families.

- Research is needed for specific studies that examine arsenic and selenium in fish. Additional research is needed to assess the potential protective role of nutrients and other factors, such as selenoneine effects on mercury (Hg) toxicity.

- More quantitative characterization is needed to assess the risk of chronic exposure to less studied contaminants such as PFAS, arsenic species, microplastics, and domoic acid to assess bioaccumulation in food chains at the levels of exposure and toxicity.

- Research is needed to characterize biomarkers of exposure to contaminants in seafood among women of childbearing age, infants, children, and adolescents. This research is needed to identify and characterize dose–response relationships between contaminants and contaminant mixtures in seafood and adverse outcomes among the children of women exposed during pregnancy and lactation.

- Additional research is needed to assess childhood health outcomes related to seafood consumption by children. This should include not only amounts and types consumed but also the age of introduction of seafood to infants and children.

- Additional research is needed to determine whether there are sensitive periods in child development during which seafood consumption or exposure to contaminants in seafood might have different effects on child health.

- Population studies that examine the effects of maternal and child seafood consumption on child health outcomes need to better characterize the seafood species (e.g., type of fish, source, and location) as well as nutrient composition and contaminant concentrations in the seafood consumed.

- Additional research is needed on the health effects of contaminant mixtures and varied exposure levels to determine applicability for these observations in seafood-consuming populations in the United States and Canada.

- Additional research is needed to assess how to effectively communicate seafood consumption recommendations to women of childbearing age, children, and adolescents.

RISK–BENEFIT ANALYSIS

The assessment of risks and benefits to human health associated with seafood consumed as a food product as well as a part of a dietary pattern can be either quantitative or semiquantitative. The four steps in the risk assessment process are (1) identification of chemical and/or microbiological hazards, (2) assessment of intake response, (3) assessment of the nature of the risk, and (4) characterization of health outcomes. The balance of positive and negative health outcomes identified in the risk assessment is used to inform policy decisions and develop guidelines for public health practitioners.

Approaches to Conducting Risk–Benefit Analyses

An evidence scan, provided by the study sponsors, identified three tiers of risk–benefit analyses (RBAs). These are:

- Tier 1: Initial—a qualitative RBA that determines whether the health risks clearly outweigh the health benefits or vice versa.

- Tier 2: Refined—a semi-quantitative or quantitative estimate of risks and benefits at relevant (toxicant, essential nutrient) exposure levels.

- Tier 3: Composite metric—a quantitative RBA that compares risks and benefits as a single net health effect value, such as disability-adjusted life year (DALY) or quality-adjusted life years (QALY).

Across the body of epidemiological evidence, the evidence scan identified differences in exposure levels and in exposure and outcome measurements and windows, questionable population representation, and generalizability of diverse and specialized study samples. From a biostatistical perspective, variation existed in the covariates, confounders, and effect modifiers that were considered. The findings from the evidence scan show the importance of sufficient planning, preparation, discussion, consensus building, and further innovation when applying evolving review methodologies, incorporating emerging findings from new studies, and exploring approaches for integrating and synthesizing evidence.

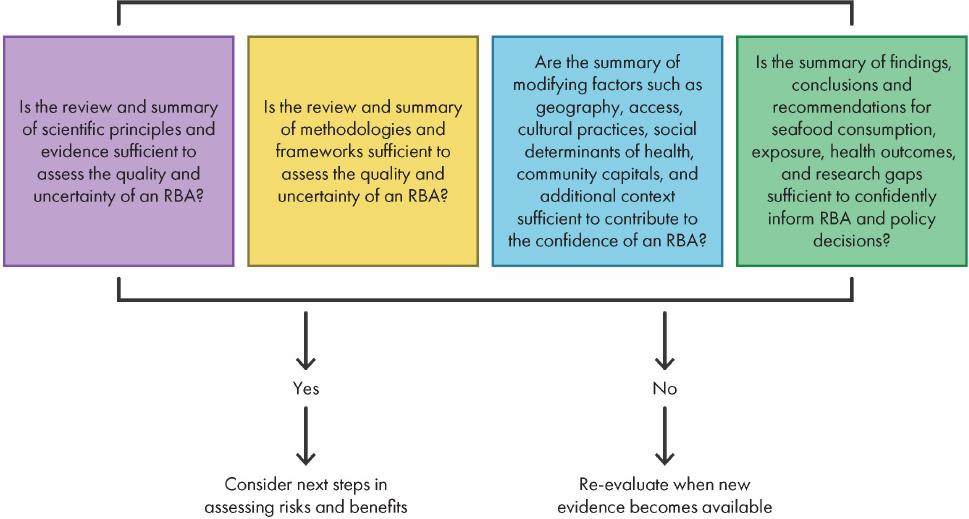

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) scientific commission recommended that risk assessors consider the risks and benefits independently and compare health outcomes to determine whether the benefits outweigh the risks or vice versa. Step 1 of the EFSA model indicates the sources of evidence used to evaluate whether the evidence is of sufficient quality and quantity to justify an RBA. Step 2 indicates the methodologies and framework for comparing risks and benefits as a single net health effect value. Step 3 identifies the factors that influence the decision of whether to conduct an RBA. Step 4 considers factors that the committee considered in developing a process for evaluating confidence and conclusions in the evaluation process. If the results demonstrate that neither a substantial risk nor benefit exists, the assessment is terminated.

A Decision Tree for Evaluating When to Conduct a Risk–Benefit Analysis

Figure S-2 shows the committee’s steps for evaluating when or when not to conduct a formal risk–benefit analysis. The committee based its steps for refining risk–benefit decision making on the EFSA model.

The committee considered a range of contextual factors—such as access to health care, access to food, community resilience, and stress—that modify the risk–benefit decision process. Specifically, higher perceived stress levels have been associated with lower adherence to a healthful dietary pattern. Social environments (family and peer influence), physical environments (schools and restaurants), and economic factors (income and socioeconomic status) also have an effect on food choice behaviors. Factors related to diversity, equity, and inclusion such as ethnicity, culture, and identity can affect food choice as well as availability.

Primary Findings and Conclusions

Findings

- The integration of diverse data sources and the heterogeneous nature of information available about risks and benefits presents a challenge when selecting metrics to adequately evaluate and compare these risks and benefits in a formal RBA. To date, many formal RBAs have focused on methylmercury (MeHg) as the contaminant and have not assessed contaminant mixtures and toxins. Many other contaminants present in mixtures showed gaps in evidence and hence were less suitable to conduct a formal RBA. Key factors influencing the conduct of RBAs include the social determinants of health at the individual level, such as poverty and health disparities, and cultural traditions and vulnerability at the community level.

NOTE: RBA = risk–benefit analysis.

- All 50 U.S. states issue voluntary fish consumption advisories on potential contaminant exposure from consuming local fish. Advisories often include specific information about contaminants found in distinct fish species and waters. The evidence available showed variability in the information included in fish advisories for how these hazards are described, and even more variability in what (or if) nutritional information is included in these advisories, yet they are an information source for consumers. A key focus was observed on risks associated with the consumption of MeHg-contaminated fish by pregnant women. Most advisories do not adequately address the risk for specific vulnerable populations, especially subsistence fishers. The committee finds that this irregularity across advisories makes comparison of risks and benefits difficult for most consumers.

Conclusions

- A risk–benefit analysis can be an excellent tool to analyze, in a transparent matter, factors that affect both benefits and risks in an integrated approach, rather than as independent domains. This integrated approach toward assessing benefits and risks positions an RBA to effectively support decision-making processes regarding fish consumption. This tool can be applied at the population and individual levels and its scope extended beyond health concerns by including costs, environmental sustainability, and ethics.

- The process for evaluating when or when not to conduct a formal risk–benefit analysis requires assessing the following four key areas: the state of evidence aided by systematic reviews of existing literature, the existence of validated approaches and metrics, an analysis of contextual factors affecting benefits or risk tailored to specific target populations, and the quality and uncertainty of the overall RBA evaluation.

- Formal risk–benefit analyses of fish consumption are seldom conducted because no comprehensive source exists that provides necessary, available data on consumption, contextualization factors, and contamination.

- Maximizing the usefulness of a risk–benefit analysis requires the integration of datasets addressing life stages, consumption patterns, information on nutrient status, exposure to contaminants, health outcomes, and contextual factors.

- Communication about potential health benefits conferred by specific nutrients in seafood is varied. The advisories reviewed by the committee were voluntary and not subject to regulation.

- Strengthening the links between a formal risk–benefit analysis, management decisions, and dietary recommendations communicated to the public can improve transparency and advance public health outcomes by ensuring that the best science informs management decisions.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 3: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration should consider conducting a risk–benefit analysis of maternal and child seafood intake and child growth and development, and, in doing so, routinely monitor data and scientific discoveries related to the underlying model and assumptions to ensure the assessment reflects the best available science.

Recommendation 4: In conducting a risk–benefit analysis, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency should include reviews of current evidence scans, systematic and supplemental reviews, approaches and metrics, benefit–harm characterization, and quality and assurance in evaluating the confidence in a risk–benefit analysis for policy decision making.

Recommendation 5: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, in collaboration with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, should create an integrated database to support risk–benefit analyses for fish consumption, thoroughly considering implications of using a metric that reflects transparency and conflicts of interest for both risk and benefit.

Recommendation 6: To maximize the use of a formal risk–benefit analysis, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in collaboration with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency should present conclusions of a risk–benefit analysis, including a risk estimate, in a readily understandable and useful form to risk managers and be made available to other risk assessors and interested parties.

RESEARCH GAPS

- Research is needed to inform the use of emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, to develop a comprehensive data integration framework to support the conduct of risk–benefit analyses.

- Research is needed to determine both the individual effect as well as the potential cumulative effects of factors that influence the conduct of a risk–benefit analysis.

- The science undergirding the conduct of a risk–benefit analysis should be periodically reviewed, such as every 3–5 years, and updated when needed.