The Role of Seafood Consumption in Child Growth and Development (2024)

Chapter: 2 Methodological Approach to the Task

2

Methodological Approach to the Task

The committee developed a systematic approach to support its synthesis of the evidence on relationships between seafood consumption and health outcomes (including behavioral outcomes), both advantageous and harmful. As part of its evidence-gathering approach, the committee commissioned an update of two systematic reviews of the literature and a de novo systematic review. The committee also gathered and reviewed publicly available information, including both original research and systematic reviews from the published peer-reviewed literature, that has become available since the previous study on these topics, Seafood Choices: Balancing Benefits and Risks (IOM, 2007). Finally, the committee commissioned analyses of seafood consumption and nutrient intake using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the Canadian Community Health Survey.

The committee’s approach to integrate scientific evidence from a range of sources to inform conclusions helped support a key goal of the study, which is to produce the most up-to-date understanding of the science on fish consumption in a whole diet context to determine whether the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Environmental Protection Agency’s current fish consumption advice (FDA, 2021) should be updated. As discussed in Chapter 1, the committee’s scientific review will also help inform FDA in its efforts through the Closer to Zero Action Plan (FDA, 2023), which launched in April 2021 and sets forth the agency’s approach to reduce the public’s dietary exposure to contaminants to as low as possible.1

SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

The sponsors provided the committee two existing systematic reviews conducted to support the Scientific Advisory Committee for the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020–2025 (DGA). These reviews covered (1) the relationship between seafood consumption during childhood and adolescence and neurocognitive development (up to 18 years of age) (Snetselaar et al., 2020a) and (2) the relationship between seafood consumption during pregnancy and lactation and neurocognitive development in children up to 18 years of age (Snetselaar et al., 2020b). The committee was asked to update these existing systematic reviews (referred to in this report as the “nutrition reviews”) and to also conduct a de novo systematic review of the relationship of toxins, toxicants, and microorganisms in seafood with health outcomes in children and adolescents (the “toxicology review”).

___________________

1 This section was modified after release of the report to the study sponsor to accurately reflect the study scope.

Scoping Reviews

Prior to conducting systematic reviews on toxicants from seafood consumed during pregnancy, lactation, childhood, or adolescence and child development and health outcomes, the Texas A&M Agriculture Food and Nutrition Evidence Center (Evidence Center) conducted a scoping review to identify toxicant exposures with sufficient evidence to warrant a systematic review, as well as gaps in the evidence. The scoping review protocol is described in Appendix C. The committee prioritized the list of outcomes to narrow the scope and inform decisions about which exposure–outcome pairs would have sufficient evidence to warrant a systematic review.

Protocols for Updated Existing and Conducting De Novo Systematic Reviews

The committee appointed a technical expert panel (TEP) composed of three consultants to develop a protocol to update the two existing systematic reviews with articles published from January 1, 2019, through May 15, 2023. The committee also asked the TEP to design a protocol for a de novo systematic review on toxins, toxicants, and micro-organisms in seafood. For consistency and to facilitate comparison between the updated nutrition systematic reviews and the new toxicology systematic review, the toxicology review protocol was generally aligned with the search strategy used in the nutrition reviews (see Appendix C). It was based on two overarching questions provided by the sponsors:

- What is the relationship between maternal seafood consumption in the United States and Canada and child growth and development?

- What is the relationship between seafood consumption in the United States and Canada during childhood and adolescence and neurocognitive development?”

The specific subquestions relevant to the toxin/toxicant systematic review are as follows:

- What are the exposures to toxins and toxicants from seafood in the perinatal period, including lactation, and childhood?

- What are the associations between seafood toxins and toxicant exposure during pregnancy, lactation, and childhood and child growth and development?

- What are the biological mechanisms of action (single actions, interactions, compound effects, and/or synergistic effects) through which toxins and toxicants from seafood potentially affect child growth and development?

For each of these three subquestions, the committee identified two additional subquestions:

- What are the differences by social, economic, and/or environmental factors (e.g., race/ethnicity, income, cumulative exposure to nonchemical stressors such as psychosocial stress and depression, cumulative exposure to environmental stressors)?

- What are the differences by preexisting disease burden in the mother or child (e.g., asthma, allergy, neurodevelopmental disorders, other developmental disorders, cardiovascular disease, growth disorders, psychomotor performance)?

To assist the committee in understanding the state of the published literature and to afford a basis for structuring the systematic reviews the sponsors provided three evidence scans: (1) epidemiology, (2) mechanisms of action, and (3) risk–benefit analysis. The first scan focused on studies of exposures from seafood and all available outcomes in all populations. The second scan reviewed the available evidence on how the composition of the seafood matrix may function as exposures within the body that have various mechanisms of action and interplay. The third scan reviewed existing risk–benefit analyses and methodologies within the published literature.

The committee asked the National Academies’ Research Center to carry out the literature search for the updated and the de novo systematic reviews. National Academies staff, working with the committee’s consultants,

created initial lists of relevant controlled vocabulary terms (Medical Subject Heading [MeSH] terms for Medline and Emtree terms for Embase). The committee then reviewed the lists and suggested additional terms. The search was carried out in Medline using PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, using Ovid for the latter two databases. Reports published in English between January 2019 and May 2023 for the nutrition updates and between January 2000 and July 2023 for the de novo toxicology review were included. Appendix C describes additional eligibility criteria for the two nutrition reviews and the toxicology review. The eligibility criteria follow the populations, exposures, comparators, outcomes, and study design (PECOD) formulation. The complete series of commissioned systematic reviews is available online in Appendix H.2 The protocols for the systematic reviews were prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023432844),3 an international prospective register of systematic reviews.

The committee developed an internal check to ensure that the search strategy was capturing known relevant studies. Individual committee members suggested five to six key articles that they expected to find in the search results. Research Center staff checked whether the search had identified the submitted articles. Audit results were consistent with expected outcomes; therefore, no further refinements were made to the literature search and the search syntax was finalized. The search strategy is available online in Appendix F.4

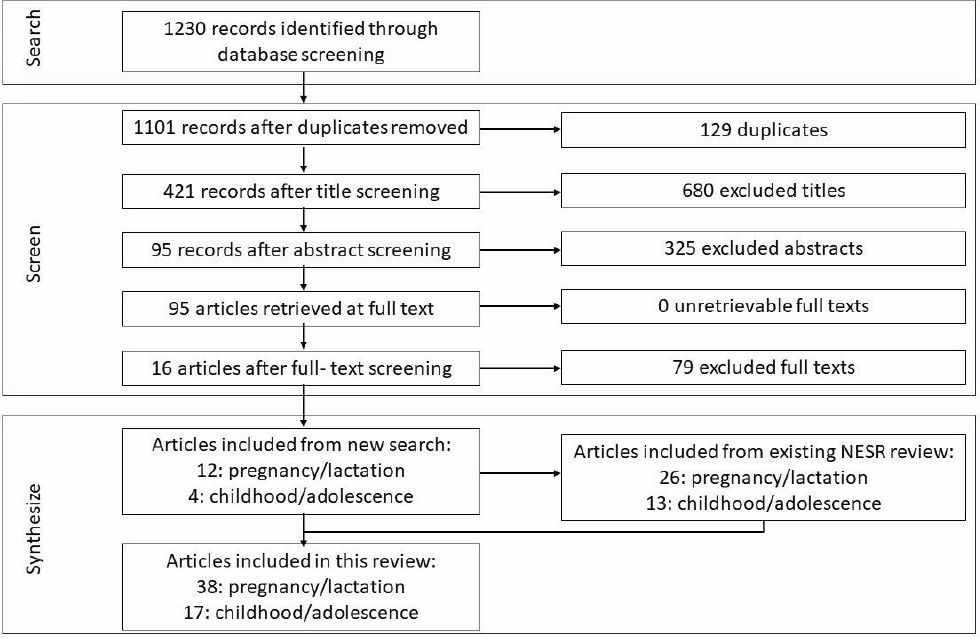

The committee then commissioned the Evidence Center to perform the updates to the two existing nutrition reviews and the new toxicology review. As noted above, the committee provided the PECOD formulation, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and search strategy for each of the systematic reviews to the Evidence Center. The Evidence Center then carried out the screening, data extraction, and risk-of-bias assessment as described in Appendix C. The PRISMA flow charts for each review are shown in Figures 2-1 and 2-2.5 For the nutrition reviews updates, there were 12 new articles related to maternal seafood consumption and 4 new articles related to seafood consumption during childhood since the time period covered by the existing systematic reviews.

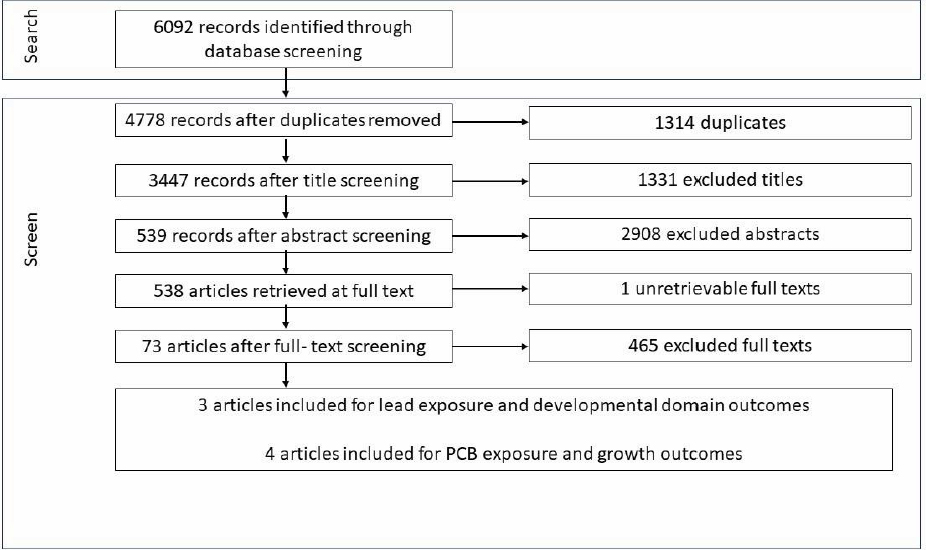

The de novo systematic review on associations between contaminants in seafood and health outcomes found 73 included articles. Prior to full data extraction, the Evidence Center conducted a scoping review and extracted high-level data from each included article (see description above). These data were used to inform committee decisions on prioritizing toxicant and outcomes relationships for further systematic review. Based on these decisions, two toxicant exposure pairs were identified for full systematic review: polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and growth and body composition, and lead and developmental domains. Four articles on PCBs and three on lead were included for data extraction (see Appendix H online for full details).6

SUPPLEMENTARY REVIEW OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

In response to the two overarching questions and specific subquestions submitted by the sponsor, the committee was interested in identifying additional health outcomes, toxic elements, and micro-organisms. Those terms not included in the commissioned systematic reviews were searched in a supplementary review of systematic reviews in the published literature. The supplementary reviews included seafood consumption and cardiometabolic, immune-related, and cancer outcomes.

To execute the supplementary reviews, the committee followed a similar process as described for the systematic reviews. The committee identified key topics relevant to its statement of task that were not included in the systematic reviews. The committee then defined search terms and eligibility criteria (Appendix D) and conducted literature searches in PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase for articles published from 2010 to 2023. The search results were uploaded to a systematic review management program (Pico Portal) for screening. Two staff independently screened each article title and abstract. Any conflicting results were discussed by the staff reviewers and

___________________

2 Appendix H can be found online at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27623.

3 See https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=448200;https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=432844 (both accessed April 10, 2024).

4 Appendix F can be found online at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27623.

5 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart depicts the flow of information through the different phases of a systematic review. For more information on PRISMA, see http://prisma-statement.org/ (accessed February 13, 2024).

6 Appendix H can be found online at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27623.

NOTE: NESR = Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review.

SOURCE: Texas A&M Agriculture, Food, & Nutrition Evidence Center.

resolved by consensus. The final full-text screening was conducted independently by a committee member and consultant team with a similar conflict resolution process as described above. Following extraction, data synthesis was conducted independently for each of the key topics.

The committee did not conduct meta-analyses or other reanalyses of data. Risk-of-bias analyses and AMSTAR 27 (or equivalent) certainty-of-evidence conclusions were considered as reported within the existing publications. In addition, the methodological quality of each systematic review identified in the supplementary review of systematic reviews was evaluated using the A Measurement Tool to Access Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR 2) quality-assessment tool (Appendix D). The AMSTAR 2 questions were answered for each article and given an overall assessment of the quality of each review. Extracted data for the supplemental systematic reviews is in Appendix D. The complete search strategy is described in online Appendix G.8

The committee was also interested in examining the association between mercury and child health outcomes using studies that did not explicitly report fish or seafood consumption. The search was focused on relevant, timely, and high-quality systematic reviews on mercury exposure during pregnancy, lactation, childhood, or adolescence on child health and development outcomes. Two reviewers screened all search results at the full-text level, and conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer. Each reviewer conducted independent assessments for each systematic

___________________

7 The sentence was edited after release of the report to the study sponsor in order to correctly identify the method used for assessing systematic review quality.

8 Appendix G can be found online at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27623.

NOTE: PCB = polychlorinated biphenyl.

SOURCE: Texas A&M Agriculture, Food, & Nutrition Evidence Center.

review that met inclusion criteria. Conflicts were discussed and resolved by the two reviewers. The AMSTAR 2 quality-assessment tool was used to assess the quality of included systematic reviews (Appendix D). A total of 53 articles were identified in the search for existing systematic reviews related to the association between mercury exposure during pregnancy, lactation, or childhood and child outcomes. Existing systematic reviews were identified for all but two prioritized outcomes. No articles were identified in the search related to blood pressure; however, a review from 2019 was identified through manual searching and included.

SEAFOOD INTAKE ANALYSES

The committee also commissioned analyses of seafood intake data from the NHANES, a nationally representative sample of the U.S. population. Data from survey cycles 2011–2012 to 2017–March 2020 were analyzed for the following age/sex subgroups of the exposed population:

- Female individuals of childbearing age (16–50 years)

- Male and female children ages 12–24 months, and 2–5, 6–11, and 12–19 years.

Usual intake of seafood was estimated using modeling approaches based on 24-hour recalls from 2 nonconsecutive days for children (2–19 years old, n = 13,171) and women of childbearing age (16–50 years old, n = 7,355) in year cycles 2011–2012 to 2017–March 2020. As seafood is known to be episodically consumed, special modeling methods are required to estimate usual intake and intake distributions from 24-hour recall data. The National Cancer Institute approach was used for such estimates (Appendix E). Analyses adjusted for complex sampling design and the contributions of multiple NHANES cycle years to the dataset. Mean usual intake and usual intake

distributions were estimated for total seafood, seafood groups high and low in long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, total protein foods (e.g., red meat, processed meat, poultry, eggs, nuts and seeds, legumes, soy), seafood species, fatty acids, and micronutrients for demographic groups above, and stratified estimates generated by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and income.

To understand consumption of common seafood species the committee used the NHANES 30-day food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), which includes questions about consumption of meals containing 31 different species (but not amounts). The frequency of seafood intake by food source (retail, restaurant, etc.), meal type (breakfast, lunch, dinner), and by the top 10 most commonly consumed species (shrimp, tuna, salmon, etc.) was analyzed by age, sex, race/ethnicity and income groups. Frequencies of the top 10 species were developed using the 30-day FFQ counts multiplied by the average seafood meal size weighted by meal type (breakfast, lunch, dinner). Average seafood meals sizes were estimated for age-sex group. A separate analysis was conducted of infants and children (n = 1,750) 6 months to 2 years of age for the same time period to examine patterns related to the timing of introduction of seafood. See Appendix E for the full methodology report.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

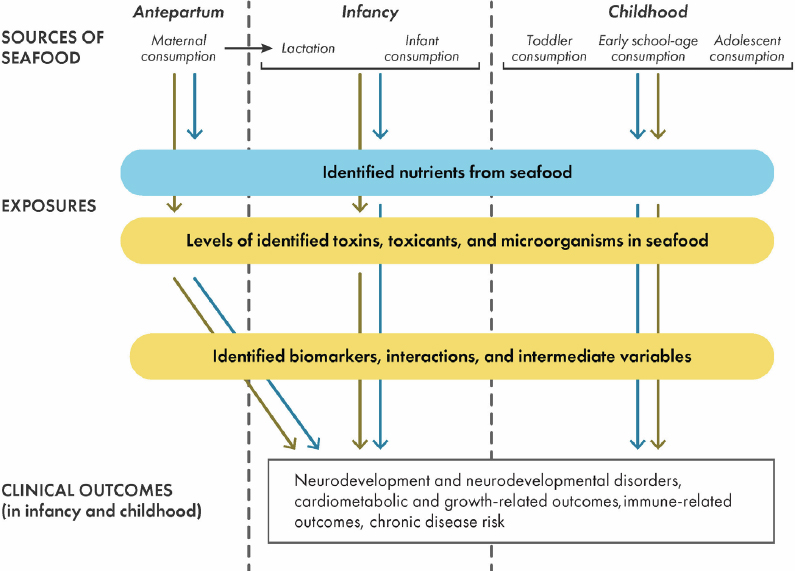

The committee was asked to develop and implement an approach to integrate scientific evidence in a transparent way and to draw conclusions (quantitative and/or qualitative) on questions related to seafood and child development outcomes. To facilitate this task, the committee developed the conceptual framework shown in Figure 2-3. The committee used iterative discussions to achieve consensus regarding the framework. The framework is organized such that relationships between sources of nutrient, toxin, toxicant, and micro-organism exposures in seafood and their relationships with clinical outcomes are depicted along the vertical direction (from top to bottom). The horizontal direction of the framework (from left to right) follows the relevant time periods of the life course of the exposed population and the outcome population. The framework was used to guide the committee’s discussions, particularly on health outcomes related to nutrient and toxicant exposures through seafood (see Chapter 6).

NOTE: Interactions refer to possible nutrient–toxin interactions.

REFERENCES

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2021. Advice about eating fish: For those who might become or are pregnant or breastfeeding and children ages 1–11 years. https://www.fda.gov/food/consumers/advice-about-eating-fish (accessed October 30, 2023).

FDA. 2023. Closer to Zero: Reducing childhood exposure to contaminants from foods. https://www.fda.gov/food/environmental-contaminants-food/closer-zero-reducing-childhood-exposure-contaminants-foods (accessed October 30, 2023).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2007. Seafood choices: Balancing benefits and risks. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Snetselaar, L., R. Bailey, J. Sabaté, L. Van Horn, B. Schneeman, J. Spahn, J. H. Kim, C. Bahnfleth, G. Butera, N. Terry, and J. Obbagy. 2020a. Seafood consumption during childhood and adolescence and neurocognitive development: A systematic review. USDA Food and Nutrition Service, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review. https://doi.org/10.52570/NESR.DGAC2020.SR0503 (accessed January 30, 2023).

Snetselaar, L., R. Bailey, J. Sabaté, L. Van Horn, B. Schneeman, J. Spahn, J. H. Kim, C. Bahnfleth, G. Butera, N. Terry, and J. Obbagy. 2020b. Seafood consumption during pregnancy and lactation and neurocognitive development in the child: A systematic review. USDA Food and Nutrition Service, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review. https://doi.org/10.52570/NESR.DGAC2020.SR0502 (accessed January 30, 2023).

This page intentionally left blank.