The Role of Seafood Consumption in Child Growth and Development (2024)

Chapter: 7 RiskBenefit Analysis

7

Risk–Benefit Analysis

This chapter presents the committee’s work to evaluate when or when not to conduct a risk–benefit analysis (RBA) relative to risk–benefit factors, including how to assess quality and uncertainty, evaluate confidence in the potential conclusions of an RBA, identify relevant factors that are additive to the findings of an RBA, and discuss any implications or applications that may inform policy decision making.

In this report, the RBA approach integrates relevant evidence from components, including nutrition, toxicology, microbiology, and epidemiology toward a comprehensive assessment of health outcomes related to seafood consumption. The goal is to facilitate evidence-based decision making and support policy development and public health advice.

APPROACH TO REVIEWING EVIDENCE ON CONDUCTING A RISK–BENEFIT ANALYSIS

The assessment of risks and benefits to human health associated with seafood consumed as a food product or part of a dietary pattern can be quantitative or semiquantitative. The steps in the process are identification of any chemical and/or microbiological hazards, assessment of intake response, assessment of the nature of the risk, and characterization of health outcomes (IOM, 2007). The balance of positive and negative health outcomes is used to inform policy decisions and develop guidelines for public health practitioners. The committee reviewed a range of evidence on how RBAs are conducted, which included an evidence scan provided by the sponsor as well as additional published literature identified in a supplementary literature review conducted by the committee (Appendix G).

ASSESSMENT OF THE STATE OF THE SCIENCE ON RISK–BENEFIT ANALYSIS

Evidence Scan on Risk–Benefit Analysis

The study sponsors provided to the committee an evidence scan on existing risk–benefit analyses related to seafood and health as an approach to exploring the current state of the evidence on seafood consumption and health outcomes and as a contribution to the committee’s review of the state of the science of risk–benefit analyses. The committee notes that apart from the evidence scan there is a preponderance of “grey” literature on this topic.1 In

___________________

1 Grey literature is defined as literature that is not formally published in books or journal articles. Examples include government reports, conference proceedings, white papers, or dissertations.

consideration of its task, however, the committee used only peer-reviewed literature and published reports from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as part of its evidence base.

The data sources for the sponsor-provided evidence scans included PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Cochrane, and Embase. The final screening results identified 176 relevant publications for full-text review. The study types included in the evidence scan were randomized controlled trials, cohort studies (prospective and retrospective), case–control studies, cross-sectional studies, ecological studies, case–cohort studies, nested case–control studies, case series, and case studies. The interventions and exposures included the following: type, duration, placebo/control (if used); exposure level quantified; dietary assessment (with emphasis on seafoods and/or with high methylmercury [MeHg], such as food records and food frequency questionnaires, and other screeners; and biochemical assays or markers of exposure such as, urinalysis, blood, hair, nail, and fecal markers.

The evidence scan also included primary health outcomes and conditions that affect health outcomes, including neurodevelopment, reproductive biology, pregnancy, psychiatric or behavioral, allergy, cardiovascular, endocrine, cancer/tumor, genetic expression, growth, immune function, inflammation, and infections.

The evidence scan identified three types of risk–benefit analyses:

- Tier 1: Initial—A qualitative RBA that determines whether the health risks clearly outweigh the health benefits or vice versa;

- Tier 2: Refined—A semiquantitative or quantitative estimate of risks and benefits at relevant (toxicant, essential nutrient) exposure levels; and

- Tier 3: Composite Metric—A quantitative RBA that compares risks and benefits as a single net health effect value, such as disability-adjusted life year (DALY) or quality-adjusted life year (QALY).

Across the body of epidemiological evidence, the evidence scan showed differences in exposure levels and in exposure and outcome measurements and windows of time, questionable population representation, and generalizability of diverse and specialized study samples. From a biostatistical perspective, variation existed in the covariates, confounders, and effect modifiers that were considered. There were also a range of statistical methods and approaches to addressing biases during the conduct of a study and in assessing the risks and effects of bias in interpreting results.

The findings from the evidence scan suggest a need for sufficient planning, preparation, discussion, consensus building, and further innovation when applying evolving review methodologies, incorporating emerging findings from new studies, and exploring triangulation approaches for integrating and synthesizing evidence.

METHODOLOGIES AND FRAMEWORKS USED TO CONDUCT RISK–BENEFIT ANALYSES

In addition to the sponsor-provided evidence scan, the committee reviewed evidence gathered in its supplemental review of the literature. Relevant studies and reports from the literature review are discussed in the following sections.

Evidence from the European Food Safety Authority Scientific Committee

In response to a request for an RBA of risks of MeHg exposure and nutritional benefits associated with consuming seafood, the EFSA Scientific Committee used previous work performed by the EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain and the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, and Allergies to create scenarios based on typical seafood consumption patterns among European population groups at risk of exceeding the tolerable weekly intake (TWI) for MeHg (EFSA, 2015). The number of servings of seafood per week were estimated that would reach both the TWI and the recommended intake (dietary reference value) for n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty

acids (LCPUFAs). Additional assumptions included that the form of mercury (Hg) was 100 percent MeHg in fish meat, fish products, fish offal, and seafood, and 80 percent in crustaceans, mollusks, and amphibians. All other foods were assumed to contain inorganic Hg.

Analysis of the scenarios showed that children, including those younger than age 3 years, exceeded the TWI for MeHg at the fewest number of seafood servings per week. The results were expressed as “total mercury” for the various product categories because Hg speciation is not performed routinely by national laboratories. The EFSA Scientific Committee identified wild-caught tuna as the source of the highest levels of MeHg exposure among all fish and seafood commonly consumed in the European Union. Inadequate data precluded full characterization of the benefits of seafood consumption from being performed. For the risk assessment of seafood consumption at the EU population level, no other representative longitudinal follow-up study was identified that could have simultaneously provided good quality data on seafood consumption and clinical/physiological endpoints in this population. The EU committee concluded that the estimated mean dietary exposures to MeHg across age groups did not exceed the TWI, except for children.

Models from the Peer-Reviewed Literature

A study by Hoekstra et al. (2013) that was identified in the evidence scan described a process for conducting a quantitative RBA of seafood consumption for the Dutch population. In their approach the researchers expressed risk and benefits using the DALY metric, and evaluated the data using a software tool, QALIBRA,2 to compare the net effect of eating seafood on health outcomes. A potential impact fraction (PIF) was used to calculate the proportional change in average disease incidence following a change in exposure of a risk factor. Specifically, the factors considered in the PIF were a decrease in the risk of fatal coronary heart disease (CHD), increase in IQ in newborns, decrease in sperm count, decrease in the production of TT4 (thyroid) hormone, and increase in the incidence of diffuse fatty liver. The health outcome scenarios were based on a population intake model of consuming 200 and 500 g of seafood per week (equivalent to about 7 and 15 oz per week). The analytical finding was expressed as the relative risk of an adverse outcome. The results indicated a net benefit for populations consuming 200 g of seafood per week.

Overall, the study concluded that the beneficial effect associated with increased seafood consumption was attributable in large part to the balance of intake against the relative burden of disease from CHD and stroke, and a decrease in thyroid hormone and sperm count. Specifically, the alternative diet scenarios resulted in a decrease in DALYs and an average net annual health benefit. A loss of IQ points owing to Hg exposure from seafood consumption was compensated for by a gain in IQ points owing to the contribution of docosahexaenoic acid in fish.

Cohen et al. (2005) investigated the aggregate effect of hypothetical shifts in seafood consumption using a modeling approach. The level of risk versus benefit was modeled as the product of exposure to the active agent (MeHg or n-3 LCPUFAs) and the dose–response relationship for that agent (incremental risk per microgram per day of MeHg, or reduction in risk per gram per day of n-3 LCPUFAs, or number of seafood servings per week). The investigators then quantified the effect of changes in seafood consumption on MeHg exposure, n-3 LCPUFA intake, and the average number of servings consumed per week.

In the model, seafood consumption was estimated for 42 species from data collected in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Continuing Survey of Food Intake by Individuals reporting years from 1989 to 1991 and the third National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey reporting years from 1988 to 1994. The authors modeled five scenarios of seafood consumption and measures to increase consumption. To aggregate disparate health effects across the population, the authors reexpressed the health effects in terms of QALYs. After accounting for uncertainties in the model, the investigators found that among women of childbearing age, a shift to consumption of low-MeHg seafood resulted in a substantial improvement in cognitive development in the offspring. Alternatively, the model showed that when women of childbearing age reduced seafood consumption, the aggregate effect on cognitive development remained positive but was substantially smaller than the women who modified their consumption choices.

___________________

2 QALIBRA is a general model for food risk–benefit assessment that quantifies variability and uncertainty.

The authors concluded that risk managers should carefully and quantitatively evaluate how the population will react to changes in consumption advice and how such reactions will affect exposure to contaminants and intake of nutrients as well as how changes in contaminant exposure and nutrient intake will affect the probability of both adverse and beneficial health effects.

Boué et al. (2015), also identified in the evidence scan, conducted a systematic review of the published literature to synthesize RBA studies associated with food consumption and summarize the current methodological options and/or tendencies carried out in the field. The final review consisted of 126 articles focused on studies of RBAs and 34 on methodological frameworks. The recommended methodology for conducting RBAs followed a risk assessment framework similar to that used in science-based research, but with a risk–benefit comparison step added. Most of the studies in the review compared nutritional benefits and adverse health effects related to fish consumption based on safety reference values. The studies reviewed identified two categories of reference values, recommendations by food safety authorities, and process and formulation designs by manufacturers.

To help public health programs know which commercial or locally caught fish species may be eaten more frequently, considering only Hg and n-3 LCPUFAs, Ginsberg et al. (2015) updated a previous RBA methodology published in 2009. The previous model predicted a net risk for neurodevelopmental outcomes for many species when risk data were calibrated against benefit data and compared with risk–benefit models, including models from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Among commonly eaten fish high in Hg, the calibrated model identified risks that are consistent with current fish advisories, although other models predicted greater net neurodevelopmental benefits.

The calibrated model was used to propose a three-step framework for setting consumption advisories:

- Set an initial consumption level based on the Hg reference dose (RfD).

- Adjust consumption estimates upward if the risk–benefit model indicates a net benefit.

- Limit fish consumption based on the saturation of benefit from n-3 LCPUFAs.

To advise the public on the frequency of consuming those species that exceed the RfD requires confidence that there is a net benefit. Upper bound and lower bound slope estimates can be used to identify where a benefit is substantial relative to uncertainties in slope estimates. Borderline benefits may not warrant increasing consumption beyond relatively minor rounding to the next whole meal, and a net risk may warrant downgrading of consumption advice. Where a clear net benefit exists, the saturation of n-3 LCPUFA benefit as introduced by FAO/WHO (2011) appears to be a reasonable way to limit meal frequency and prevent excessive risk of Hg exposure.

Simple n-3 LCPUFA-to-Hg ratios in fish tissue have been proposed as a useful screen for estimating risk–benefit trade-offs associated with consuming a particular species. The simplicity of such an approach could encourage more species sampling. In this approach, an n-3 LCPUFA-to-Hg ratio of 30 or greater would represent a clear neurodevelopmental benefit (see Table 4 in Ginsberg et al., 2015). This approach could also help assessors determine when it may be appropriate to recommend that it is acceptable for consumers to exceed the RfD on a species-specific basis.

In a different approach, Ginsberg and Toal (2009) developed a method to quantitatively analyze the net risk–benefit of individual fish species based on MeHg and n-3 LCPUFA content, which was intended to allow a more nuanced approach to providing advice about risks of consuming seafood. This study identified dose–response relationships for MeHg and n-3 LCPUFA’s effects on CHD in adults and neurodevelopment in infants. The investigators used the MeHg and n-3 LCPUFA content of 16 commonly consumed species to calculate the net risk–benefit for each species. The results indicated that the estimated benefits from n-3 LCPUFAs outweighed the risks from MeHg for some species (e.g., farmed salmon, herring, trout), while the opposite was true for others (e.g., swordfish, shark). Other species were associated with a small net benefit (e.g., flounder, pollack, canned light tuna) or a small net risk (e.g., canned white tuna, halibut). The results were used to place fish into one of four meal frequency categories. However, the advice was considered provisional owing to limitations in the underlying dose–response information.

The overall results of the study showed a framework for risk–benefit analysis that could be used to develop categories of consumption advice ranging from do not eat to unlimited, with the caveat that the term unlimited may

need to be moderated for certain fish (e.g., farm-raised salmon) because of other contaminants and end points (e.g., cancer risk) that may be present. Furthermore, the authors proposed a tailored approach because of uncertainties in the underlying dose–response assessment. Although showing possible directions for species-specific advisories, the analysis also identifies key research areas—such as examining the adverse effects of MeHg on cardiovascular outcomes in adults—for improving RBAs for fish consumption.

Summary of Evidence on Methodologies Used to Conduct Risk–Benefit Analyses

The committee determined that a quantitative approach to fish type and specific toxicant health impact could be useful for assessing risk compared with benefits where one size does not fit all, and where the concentrations of MeHg by fish species provide more appropriate guidance for the public. However, this approach could benefit from identifying further directions needed for high consumers and providing specific calculations for updating current information on both nutrient and toxicant.

MODELING BENEFITS AND RISKS OF FISH CONSUMPTION

FDA’s 2014 quantitative risk assessment (also discussed in Chapter 6) estimated the effects on the developing nervous system of the fetus from the consumption of commercial fish during pregnancy (FDA, 2014). The assessment also reviewed the evidence on the effects of fish consumption by young children on their own neurodevelopment. The methodology for this assessment included exposure modeling and dose–response modeling. Exposure modeling was based on previously published work by Carrington and Bolger (2002). The dose–response models were developed from results from selected observational research studies in humans. The preferences for selecting research results for input into the dose–response modeling included outcomes for neurodevelopment that were biologically plausible, sufficiently detailed, and reasonably consistent with effects seen in other studies.

The data and results from which the Hg dose–response relationship with IQ was derived established that IQ is a representative indicator of effect, and sufficient detail was available to conduct dose–response modeling. The results were biologically plausible and reasonably consistent with effects seen in other studies. Furthermore, the MeHg effects are not likely to have been substantially confounded as exposure levels were relatively high and the combined study population was relatively large.

The assessment estimates that for each of the endpoints modeled, consumption of commercial fish during pregnancy is beneficial for most children in the United States. On a population basis, average neurodevelopment is estimated to benefit by nearly 0.7 of an IQ point (95% confidence interval [CI] of 0.39–1.37 IQ points) from maternal consumption of commercial fish. For comparison purposes, the average population-level benefit for early-age verbal development is equivalent in size to 1.02 of an IQ point (95% CI of 0.44–2.01 IQ size equivalence). For a sensitive endpoint as estimated by tests of later age verbal development, the average population-level benefit from fish consumption is estimated to be 1.41 verbal IQ points (0.91, 2.00).

The assessment also estimates that a mean maximum improvement of about three IQ points is possible from fish consumption, depending on the types and amounts of fish consumed. Fish lower in MeHg generally produce greater benefits and have a lower likelihood of an adverse net effect than fish higher in MeHg. The amount of fish consumed that is needed to obtain the greatest benefit, meaning the greatest gain in IQ points, can vary depending on fish species, but in the hypothetical scenarios modeled, the largest benefits on a population-wide basis occurred when all pregnant women ate 12 oz of a variety of fish per week.

By contrast, an FDA survey of young women indicated that pregnant women on average ate slightly less than 2 oz of fish per week (FDA, 2017). The assessment modeled the net effects of maternal fish consumption on early-age verbal development as a representative indicator of the net effects from fish consumption on neurodevelopment generally. This updated assessment focused on IQ but retained the modeling approach for early-age verbal development for purposes of comparison. The estimated effects on both endpoints were not identical, but they were consistent and appear to provide a plausibly narrow range in which net effects are likely to fall. The assessment also included modeling based on scores of later-age verbal development because the scores appear to

reflect a particular sensitivity to the effects of both MeHg and nutrients in fish. The results allow for a comparison between a particularly sensitive endpoint and more representative endpoints.

The FDA assessment also included species-by-species modeling for 47 selected species and market types of commercial fish. This included both population-level modeling, which estimates percentiles of the population experiencing various net effects, and individual-level modeling, which estimates the net effects of eating commercial fish during pregnancy on IQ measured through 9 years of age as indicative of how eating fish can affect neurodevelopment and verbal development. There is evidence that the neurodevelopmental test results for this endpoint are sensitive to both detrimental effects of MeHg exposure (e.g., the Boston Naming Test as administered in the Faroe Islands study) and beneficial nutrients in fish consumed by the mother.

Nauta et al. (2018) identified 10 key challenges to be addressed when developing an RBA, such as application of different definitions of risk or benefit. For example, the term benefit can be used for anything from the agent causing the health effect to the probability and magnitude of the effect. Another challenge is how to assess health effects in an RBA. The approach chosen usually depends on whether the health effects associated with food components are obtained from animal experiments or human observational studies. A top-down approach to human consumption data is presented as a more feasible approach, particularly if data have a large n value and the data needs are diverse.

Nauta et al. (2018) also discussed dose–response models as well as the modeling process, which is often based on relative risk, although the uncertainties can be large. The committee notes that the level of scientific evidence needed to identify a risk may be low because indication of a risk is sufficient for scientific validation. Lastly, the study concluded that risk communication is a key pillar in risk analysis and should be a part of RBAs applied to foods.

Future Work

With the availability of new evidence on the risks and benefits of fish consumption, FAO and WHO in October 2023 conducted an Expert Consultation on the Risks and Benefits of Fish Consumption to update the previous report (FAO/WHO, 2011) on this topic. Although the full report has not yet been published, the “Meeting Report” with executive summary was published on November 1, 2023.3

FAO and WHO commissioned a systematic literature review from the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research (IMR) that was used to generate a FAO/WHO background document on the risks and benefits of fish consumption to inform the expert consultation. The IMR review covered existing evidence scans, including the following:

- Benefit and Risk Assessment of Fish in the Norwegian Diet published by the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment (Andersen et al., 2022);

- report from the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF International, 2018);

- reports from the EFSA containing expert opinion on MeHg (EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain, 2012) and dioxins (EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain, 2018); and

- additional publications identified from a systematic literature search to identify publications not considered in these prior evidence scans.

After reviewing the background document on the risks and benefits of fish consumption, the 2023 Joint FAOWHO Expert Consultation agreed on the following overall conclusions regarding human health benefits from fish consumption:

- Fish consumption provides energy, protein, and a range of other nutrients important for health.

- Fish consumption is part of the cultural traditions of many peoples. In some populations, fish are a major source of food, animal protein, and a range of other nutrients that are important for health.

___________________

3 Available at https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/food-safety/jecfa/summary-and-conclusions/jecfa-summary-risks-and-benefitsof-fish-consumption.pdf?sfvrsn=af40f32c_5&download=true (accessed February 29, 2024).

- “Strong evidence exists for the benefits of total fish consumption during all life stages: pregnancy, childhood, and adulthood. For example, associations are found for maternal consumption during pregnancy with improved birth outcomes and for adult consumption with reduced risks for cardiovascular and neurological diseases. This evidence for health benefits of total fish consumption reflects the overall effects of nutrients and contaminants in fish on the studied outcomes, including nutrients and contaminants not specifically considered in the evidence review.”

- “Benefits derived from general population studies and individual effects will vary depending on overall diet (e.g., selenium intake, exposure to other contaminants) and characteristics of consumers (e.g., n-3 LCPUFA status and individual susceptibility) and fish consumed (e.g., fish species and food preparation methods).”

- Risk–benefit assessments at regional, national, or subnational levels are needed to refine fish consumption recommendation, which should consider local consumption habits, contamination levels, and nutrient content of fish species present, as well as the population of interest’s nutritional status, cultural habits, and demographics.

Summary of Evidence on Modeling Benefits and Risks of Fish Consumption

It is a reasonable hypothesis that fish consumption by young children can affect their neurodevelopment. They may be especially vulnerable to MeHg but could also be especially responsive to the beneficial nutrients in fish. Consistent evidence indicates that young children can benefit from fish consumption, but the evidence is not consistent with regard to whether young children are especially vulnerable to adverse effects from MeHg from postnatal exposure.

DEVELOPING A FRAMEWORK FOR CONDUCTING A RISK–BENEFIT ANALYSIS

The risk–benefit framework is based on three key elements: assessment of risks and benefits, management of risks and benefits, and communication of risks and benefits. Boué et al. (2022) proposed an approach to assessing the effect of diet on public health using RBA methods that simultaneously consider both beneficial and adverse health outcomes. Their aim was to develop a harmonized, transparent, and documented methodological framework for selecting nutritional, microbiological, and toxicological RBA components. The investigators used a stepwise approach to component selection that involved conducting a comprehensive literature search to first identify an initial, long list of components to consider for each of the three domains. To trim each domain’s long list of components to a shorter list, they applied a series of predefined criteria that were established based on occurrence and severity of health outcomes related to these components. The final list of components was developed by refining the short list based on availability and quality of data for a feasible inclusion in the RBA model.

The final list included the components and health outcomes to be considered in the RBA to estimate the overall public health impact of using the DALY composite metric. The limitations of using DALYs as a composite metric to quantify health impact include that the criteria for occurrence and severity may not specifically distinguish between the general populations and the vulnerable populations nor identify potential allergic reactions. Additionally, the use of DALYs as a metric in analysis could limit the inclusion criteria because of data model gaps. The investigators thus concluded that the RBA should not be considered as a one-dimensional process, rather as a process that could benefit from the integration of environmental, economic, and sociological assessments. The committee’s assessment of this study was that it presented an insufficient and complicated approach to using RBA as a means of harmonizing the findings.

Membré et al. (2021) also shows some of the complexity involved in attempting to conduct an accurate RBA that can reflect, to the extent possible, the net risks and benefits to a population. For example, complications can arise from the differences between specific population groups and the general population, from the challenges to obtaining the large amount of data often required for an RBA, and from the substantial time required to perform it. Additional factors influencing the conduct of an RBA include the availability of the food type, costs, personal preference, and food quality, among others. Separate studies often result in conflicting messages, and several

examples were given. Although fish is one of the most widely studied foods in an RBA, it can be highly complicated and difficult to capture the overall effect of fish consumption on health among different populations. Often, large states of risk and benefit must be tailored for specific groups. Hence, clear communication of the results or findings is essential to ensure that consumers can make balanced and objective choices.

As stated by Membré et al. (2021), the first message component is often the most influential. An accurate and effective RBA is essential to supporting informed decision making by both the target population and specific subgroups within it. Transparency about the data and input incorporated into an RBA are important for public acceptance of the RBA and to help promote behaviors aligned with the RBA’s results.

Scherer et al. (2008) conducted a comparative analysis of state websites to assess health messages accessible to vulnerable populations, including pregnant women and women of childbearing age. These advisories were issued by state, tribal, and local governments. The study demonstrated that of the 48 fish consumption-related state advisories that were examined, 90 percent targeted pregnant women and 58 percent targeted women of childbearing age. Six of the 48 advisories mentioned only one contaminant (Hg), and the other 42 mentioned anywhere from 2 to 12, most frequently mercury, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), chlordane, dioxin, and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane. Beneficial health effects mentioned were limited to effects associated with n-3 fatty acids found in fish. The two states without advisories at the time of the analysis, Alaska and Wyoming, subsequently issued guidelines for fish consumption.

Scherer at al. (2008) attempted to answer the question, do advisories convey risk and benefit information about fish that is sufficient to provide context for the advice offered? Advisories provided numerous recommendations for consumption frequency across multiple groups. For children, the specific age ranges mentioned varied from children younger than 6 years to those children younger than 18 years. Thirty-eight percent of advisories were offered in non-English language, and that language was Spanish only. All advisory websites reviewed (except for Nebraska) offered meal frequency advice, although states varied by whether they issued such advice in units per week, per month, or per day. Some websites referenced the 2004 Environmental Protection Agency/FDA recommendations to consume up to 12 oz per week, while 75 percent provided meal size and 10 percent targeted sensitive populations. Some websites also provided advice about preparation and cooking.

In 2011, the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) issued a report and framework for the assessment of health benefits or risks of fish consumption to guide public health authorities and decision making (FAO/WHO, 2011). Although several potential contaminants can be present in fish, MeHg and dioxin are the major toxicants addressed in the JECFA report. The health benefits of fish consumption or dietary intake of n-3 LCPUFAs are often assessed using imprecise dietary estimates, whereas health risks of contaminants are often assessed using objective biomarkers. After reviewing the literature, JECFA compared the effects of prenatal exposure to n-3 LCPUFAs and MeHg on child IQ, and exposure to n-3 LCPUFAs and dioxins on mortality. Several meta-analyses have established linear dose–response relationships between dietary exposure to n-3 LCPUFAs and MeHg and child IQ.

The JECFA report concluded that convincing evidence exists for benefits of maternal fish consumption during pregnancy on neurodevelopment in their children. The JECFA further concluded that their differing quantitative analyses from different perspective cohorts, each employing different metrics and divergent assumptions, showed consistent dose–response relationships between maternal fish consumption and child IQ. Using a central estimate of MeHg risk, neurodevelopmental risks of not eating fish exceeded risks of eating fish for up to at least seven 100-g servings per week and MeHg levels up to at least 1 µg/g.

When comparing the benefits of n-3 LCPUFAs with the risks of MeHg among women of childbearing age, maternal fish consumption was found to lower the risk of suboptimal neurodevelopment in their offspring compared with the offspring of women not eating fish. At levels of maternal exposure to dioxins (from fish and other dietary sources) that do not exceed the provisional tolerable monthly intake of 70 pg/kg body weight established by JECFA for polychlorinated dibenzodioxins, polychlorinated dibenzofurans, and coplanar PCBs, neurodevelopmental risk for the fetus was negligible. From this study, the committee determined that among infants, young children, and adolescents, available data are currently insufficient to derive a quantitative framework of the health risks and health benefits of eating fish.

Summary of Evidence on Developing a Framework for Conducting a Risk–Benefit Analysis

The studies that the committee reviewed on addressing the risk and benefits of seafood consumption focused largely on pregnant women as one of the most vulnerable subpopulations. While some analyses included dioxins, most RBAs targeted MeHg as the contaminant of concern. From the benefit perspective, there was early recognition of the role of nutrition independently, and as a component of a broader public health approach. Together, the evidence from meta-analyses comparing dietary exposure of n-3 LCPUFAs and MeHg exposure with child IQ indicate that maternal fish consumption may be protective against potential toxic effects of MeHg exposure. However, in its framework for assessing health benefits or risks of fish consumption, the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives determined that there were insufficient data to develop an RBA for infants, children, and adolescents (FAO/WHO, 2011).

SCIENTIFIC PRINCIPLES UNDERPINNING A RISK–BENEFIT ANALYSIS

FAO/WHO (2023) identified principles for the analysis of risks versus benefits intended for application in the framework of the Codex Alimentarius. The objective was to provide guidance to the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC) and to JECFA to ensure that the food safety and health components of Codex standards and related texts are based on the analysis. Within the framework of CAC and its procedures, the responsibility for providing advice on risk management lies with CAC and its subsidiary bodies (risk managers), while the responsibility for risk assessment lies primarily with JECFA.

The general aspects of RBA used in the Codex report included consistent application, openness, transparency, and documentation. Analyses are conducted in accordance with both the statements of principle concerning the role of science in the Codex decision-making process and the extent to which other factors are considered and the statements of principle relating to the role of food safety risk assessment. Moreover, analyses are evaluated and reviewed as appropriate in light of newly generated scientific data. The RBA is intended to follow a structured approach comprising three distinct but closely linked components—risk assessment, risk management, and risk communication—with each component integral to the overall risk analysis.

Components of a Risk–Benefit Analysis

The three components of an RBA (risk assessment, risk management, and risk communication) should be documented fully, transparently, and systematically, and applied within an overarching framework for management of food-related risks to human health. While respecting legitimate concerns to preserve confidentiality, documentation should be accessible to all stakeholders. Furthermore, effective communication and consultation with stakeholders should be ensured throughout the analysis. There should also be a functional separation of risk assessment and risk management, to ensure the scientific integrity of the risk assessment, to avoid confusion over the functions to be performed by risk assessors and risk managers, and to reduce any conflict of interest. However, RBA is an iterative process, and interaction between risk managers and risk assessors is essential for practical application. When there is evidence that a risk to human health exists, but scientific data are insufficient or incomplete, CAC should not proceed with developing a standard, but should consider detailing a related text, such as a code of practice, provided that such a text would be supported by the available scientific evidence.

Uncertainty

As precaution is an inherent element of RBA, many sources of uncertainty exist in the process of risk assessment and risk management of food-related hazards to human health. The degree of uncertainty and variability in the available scientific information should be explicitly considered in the risk analysis. Where there is sufficient scientific evidence to allow Codex to proceed to elaborate a standard or related text, the assumptions used for the risk assessment, and the risk management options selected, should reflect the degree of uncertainty and the

characteristics of the hazard. Lastly, the needs and situations of developing countries should be specifically identified and considered by the responsible bodies in the different stages of the risk analysis.

Risk Assessment Policy

The FAO/WHO (2023) Risk Assessment Policy posits that the determination of a risk assessment policy should be included as a specific component of risk management. It should be established by risk managers in advance of risk assessment in consultation with risk assessors and all other interested parties. The goal of this procedure is to ensure that the risk assessment is systematic, complete, unbiased, and transparent. The mandate given by risk managers to risk assessors should also be as clear as possible and, where necessary, risk managers should ask risk assessors to evaluate the potential changes in risk resulting from different risk management options.

Summary of Evidence on Scientific Principles Underpinning a Risk–Benefit Analysis

In their assessment of risk, FAO/WHO (2023) stated that the scope and purpose of the particular risk assessment being carried out should be clearly stated and in accordance with risk assessment policy. The committee’s review of the evidence suggests that nutritional concerns may be prevalent in performing an RBA, as nutrients in themselves may pose both risks and benefits. Examples of risk include adverse effects of overconsumption, effects of adverse absorption of other nutrients, interaction among nutrients, and effect on other nutrients such as lowering their absorption or use.

APPROACH TO CONDUCTING A RISK–BENEFIT ANALYSIS

In 2010, the EFSA Scientific Committee designed a framework for performing an RBA with foods (EFSA, 2010). Its guidance acknowledges that sufficient evidence is lacking and proposes following a four-step risk assessment process. Once a problem has been formulated an initial assessment is performed; then a refined assessment and comparison of risks and benefits is made using a composite metric.

In a subsequent scientific opinion EFSA (2015) used a clear approach for establishing a risk overview and identifying data needed to assess fish consumption. This included work previously performed by the EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain and the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, and Allergies to create scenarios based on typical seafood consumption patterns among European population groups at risk of exceeding the TWI for MeHg. The number of fish servings per week was estimated that would reach the TWI and the dietary reference value for n-3 LCPUFAs. The process and results of this activity were described earlier in the chapter, where it was reported that the estimated mean dietary exposures to MeHg across age groups did not exceed the TWI, except for children. No representative longitudinal follow-up data were available, however, that could have provided the information on seafood consumption and health outcomes that is needed for risk assessment (or for full characterization of benefits) of fish consumption at the level of the EU population.

Because of the variety of fish species consumed across the European Union, it is not possible to make general recommendations for fish consumption. The EFSA Scientific Committee therefore recommended “Each country needs to consider its own pattern of fish consumption and carefully assess the risk of exceeding the TWI of methylmercury while obtaining the health benefits from consumption of fish/seafood.”

Summary of Evidence on an Approach to Conducting a Risk–Benefit Analysis

In its assessment of the EFSA (2015) report the committee identified inadequate data and uncertainties for fish species, season, location, diet, life stage, and age, as well as undefined regional differences as factors that had a major effect on both the nutrient and contaminant levels reported. Assessment of risks and benefits is further complicated by additional uncertainties in available epidemiological studies about actual serving sizes and actual contents of the potentially active positive and negative components in the seafood consumed.

STEPS IN EVALUATING WHEN OR WHEN NOT TO CONDUCT A RISK–BENEFIT ANALYSIS

The committee’s review of the EFSA (2015) report along with additional evidence from peer-reviewed published literature led to the following interpretation of when or when not to conduct a risk–benefit analysis for seafood consumption by women of childbearing age, children, and adolescents.

Initial Assessment in Determining the Need for a Risk–Benefit Analysis

Because RBAs have an inherent requirement for concurrently evaluating both risks and benefits from seafood consumption, any evaluation should combine risks and benefits into a matrix that represents the overall assessment of a particular seafood. Risks are more likely to be included in an RBA leading to a potential bias in the RBA. The imbalance in the required level of scientific evidence for risks versus benefits demands a shift from the RBA as a sum of risks and benefit assessment to the RBA as a well-documented risk–benefit assessment.

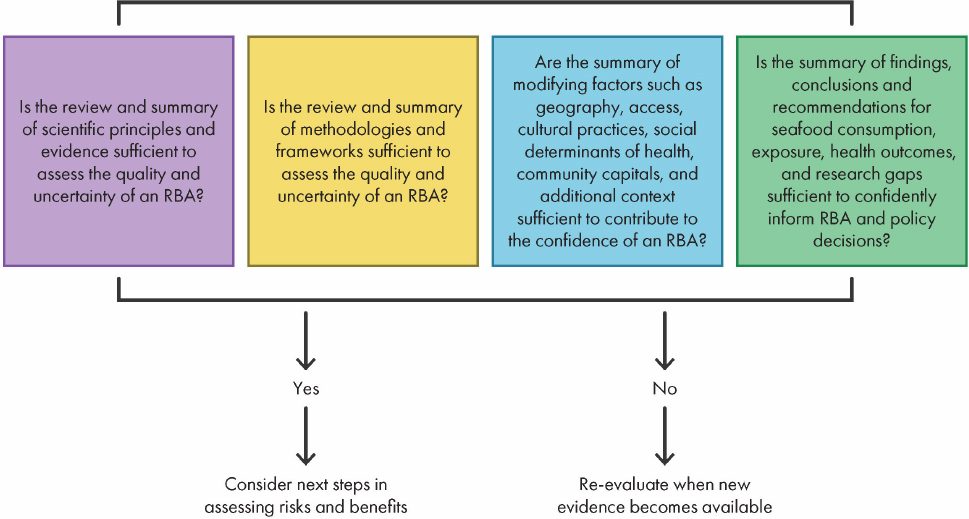

Refining the Initial Assessment in Determining the Need for a Risk–Benefit Analysis

The EFSA Scientific Commission recommended that risk assessors consider risks and benefits independently and compare health outcomes to determine whether the benefits outweigh the risks or vice versa. If results demonstrate that neither a substantial risk nor benefit exists, the assessment is terminated. The first and second questions are derived from the model proposed by the EFSA Scientific Commission as it asks whether the scientific principles and evidence as well as the methodology supports assessment of both quality and uncertainty. The third question asks whether modifying factors and additional context are sufficient to establish confidence in the RBA. The final question asks whether the findings, conclusions, recommendations, and data gaps are sufficient to inform policy decision making (EFSA, 2017).

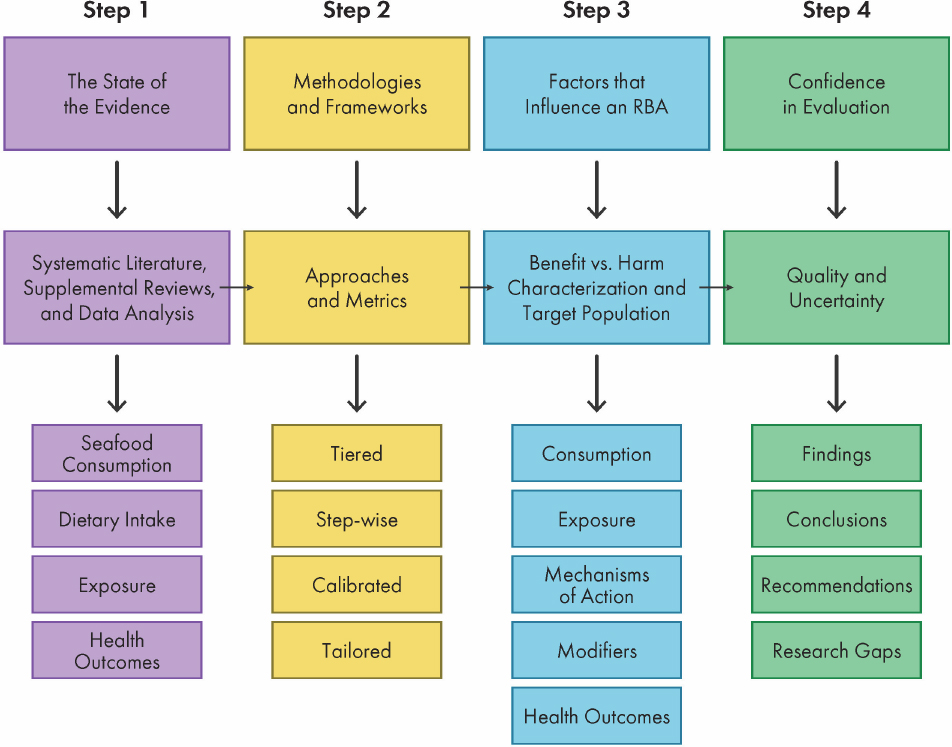

Figure 7-1 shows the committee’s steps in the evaluating when or when not to conduct a formal risk–benefit analysis. The committee based its steps for refining risk–benefit decision making on the EFSA (2015) model. Step 1 of the model indicates the sources of evidence used to evaluate whether there is sufficient evidence to justify an RBA. Step 2 indicates the methodologies and framework for comparing risks and benefits as a single net health impact value. Step 3 identifies the factors that influence the decision of whether or not to conduct an RBA. Lastly, step 4 considers factors that the committee considered in developing a process for evaluating confidence and conclusions in the evaluation process.

Summary of Evidence Reviewed on Evaluating the Need for a Risk–Benefit Analysis

The committee notes that the EFSA guidance does not include critical factors such as socioeconomics, diversity, equity, inclusion, access to health care, and other considerations such as mechanisms of action and modifiers, which are essential components of the committee’s charge. Therefore, the committee considered the following:

- inclusion of nutritional benefits;

- level of contaminant and microorganism exposure;

- mechanisms of action such as biomarkers, interactions, and intermediate variables;

- modifiers such as geography, access, dietary, and cultural practices;

- environmental stressors, including dimensions of community resilience;

- clinical outcomes relative to risk;

- presence of social determinants of health in the literature; and

- diversity, equity, and inclusion principles in demographic data, data gaps, and recommendations (see Chapters 4 and 5).

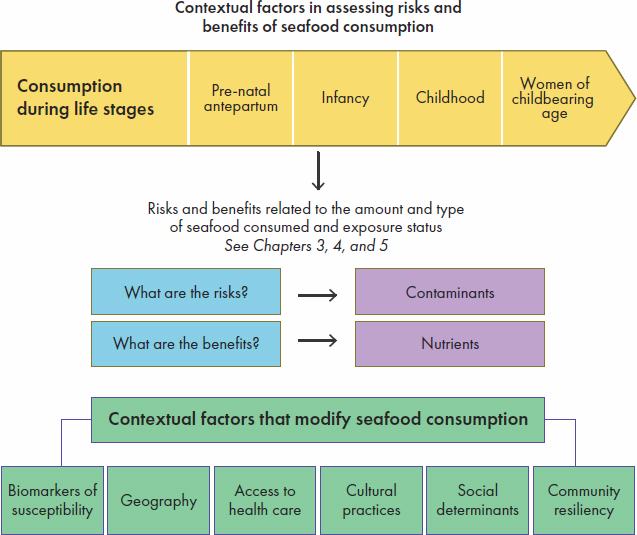

The committee reviewed the summary of evidence on health outcomes associated with potential risks factors identified in Chapter 6. Studies and reports on those factors that could potentially modify the decision-making process in evaluating whether to conduct an RBA were identified in a subsequent search and are summarized below. The committee considered exposure as it relates to consumption across the life stages of interest, meaning prenatal, infancy, and childhood as described in the analytical framework as important to understanding the interactions between nutrients consumed in seafood and health outcomes (Chapter 6).

A BASIS FOR DECISION MAKING

The committee’s review of evidence on nutritional characteristics and potential toxicants in seafood, along with evidence on health outcomes associated with consumption, led to its overarching conclusion that seafood has the potential to exert both health benefits and health risks. Risk–benefit managers should have the ability to weigh those risks against the benefits based on either a qualitative or quantitative RBA. Implied in the decision-making process is that an imbalance exists between risks and benefits that would influence the need for an RBA. Important questions that risk managers should ask are the following:

- What is the totality of the evidence on benefits and risks associated with seafood consumption?

- What are the implications of modifiers of benefit or risk, such as among populations with high vs. low seafood consumption?

- How is the balance between the risks and benefits characterized?

- What is the balance between risks and benefits? Does the risk exceed any benefit or vice versa?

- Can the benefit only be derived by exposure to seafood?

- For example, will a supplement of n-3 LCPUFA provide the same benefit as consumption of fish? That is, does the analysis need to consider the complexity of a food (nutrients, food components, food matrix, overall dietary pattern with or without seafood, etc.)?

- What is contaminant exposure relative to the TWI?

- When can an existing RBA be adapted to the population of interest?

- Is there relevant evidence in the population of interest that should be factored into the decision-making process?

To be able to answer these questions requires both strength and adequacy of evidence to support an RBA. In this report the committee searched for new evidence published since the report Seafood Choices: Balancing Benefits and Risks (IOM, 2007) to understand the totality of evidence on both benefits and risk associated with consuming seafood and determined that the outcome of each step of an RBA must include a narrative of the strengths and weaknesses of the evidence base as well as the uncertainties.

The report Guidance on the Use of the Weight of Evidence Approach in Scientific Assessments (EFSA, 2017) states that the purpose of weighing evidence is to assess the relative support for potential answers to a scientific question, in this case, in support of an RBA. In some circumstances, the evidence supports only one answer with certainty. It is more often the case that multiple answers are possible, each with varying levels of support. Thus, a conclusion should state the range of answers that are possible rather than choose a single answer.

Assessing Quality and Uncertainty

The quantitative metric that is most often used in published RBAs involving food is the DALY. The DALY is increasingly used for risk ranking and in assessing the burden of disease. It is used as an aid to policy makers for decision making about where to spend available resources. When separate health effects need to be aggregated across populations, this analysis can also be expressed as QALYs, which are a measure of health impairment that takes into account changes in longevity and quality of life.

In considering seafood consumption, specifically in the United States and Canada, the committee’s assessment was complicated by the finding that many pregnant women and young children do not consume large amounts of seafood (see Chapter 3). Furthermore, much of the data and many of the studies reviewed by the committee came from the European Union and countries outside of the United States and Canada.

Mapping the Decision-Making Process

The committee defined the parameters of risk by including toxins, toxicants, and micro-organisms and defined benefits by considering dietary intake, dietary patterns, and nutrients. In assessing the risks and the benefits, the committee included mechanisms of action such as biomarkers of susceptibility, interactions, and intermediate variables, as well as positive and negative modifiers such as geography, access, dietary patterns, cultural practices, social determinants of health, and community resilience. Lastly, the committee focused on the positive and negative health outcomes relative to growth and development, which includes neurodevelopment, cardiometabolic profiling, immune function, and disease, both chronic and acute. The committee developed a decision tree that takes a systematic approach to assessing when or when not to conduct a risk–benefit analysis for seafood consumption for the target population (Figure 7-2).

COMMUNITY RESILIENCE AND ACCESS TO HEALTH CARE

An example of community resilience is presented in the National Academies report Advancing Health and Resilience in the Gulf of Mexico Region: A Roadmap for Progress (NASEM, 2023). The goal of the report was to advance the development of sustainable systems that support activities focused on health and community resilience. The report identified four key roadblocks to achieving resiliency: (1) lack of a uniform systems approach to program development and service delivery; (2) incomplete, ineffective, and uncoordinated efforts to capture data; (3) insufficient resources reaching communities in need; and (4) an enduring failure of current systems to effectively account for the role and multiple dimensions of equity in rendering communities persistently vulnerable. The report then identified four overarching pillars corresponding to the four roadblocks: data, infrastructure, human capital, and governance.

NOTE: Steps 1–4 include hyperlinks to respective content in the report.

The report recommended that agencies within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services- the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, as well as external partners, such as the U.S. Census Bureau, should be involved in developing the data pillar. The infrastructure and governance pillars included recommendations for active inclusion of state and legislative leadership with meaningful engagement of communities at state and local levels. The human capital and funding pillar recommendation included public participation to identify specific needs and priorities as well as supports that integrate with community resilience activities. Finally, the report recommended that both federal agencies and philanthropic funding be considered as a means to address issues identified in the report, and that funders should be explicit about their long-term research agendas, research gaps, and funding availability and sustainability expectations.

Social Determinants Influencing Seafood Consumption

Social determinants are defined as the conditions in environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks. Access to healthy foods is a potential determinant of nutritional health. A study by Guenther et al. (2009) used the Healthy Eating Index–2005 (HEI-2005) to compare food choices between higher-income and low-income individuals (family income less than 130 percent of poverty). The study found that, compared to higher-income

individuals, lower-income individuals had significantly lower scores for vegetables, legumes, and whole grains, and higher scores for sodium (indicating a lower intake). However, there was no significant difference in total HEI-2005 scores among children ages 2–18 years by income level.

Among Indigenous female adolescents in Canada, aged 15–22 years, Hanemaayer et al. (2022) assessed the effects of determinants that included social environments (family and peer influence), physical environments (home, schools, and restaurants), and economic factors (income and socioeconomic status) on food choice behaviors. This study found that the built environment had an important influence on food choice, specifically the home and school settings. Family was found to be a facilitator of consistency and health choices, whereas the social environment, such as peers and community relationships, were barriers to healthy food choices. Cost had a detrimental influence on both food choice and regularity of meals. The ecological environment was not a consistent influence on food choice except seasonal consumption of traditional foods.

To understand the role of social factors, such as family structure, parental employment, and education level, as determinants of consumption of seafood and intake of n-3 LCPUFAs in children and adolescents Martínez-Martínez et al. (2020) administered a food frequency questionnaire to parents of school-age children to capture intake frequency and amount. This study identified dietary habit and food familiarity as well as ease of preparation as factors potentially contributing to low frequency of fish consumption. Additionally, the analysis found significantly lower consumption of fish high in n-3 LCPUFAs among children and adolescents whose mothers worked outside the home. An interesting finding was that children and adolescents whose mothers attained a secondary school education had lower intakes of n-3 LCPUFAs than those whose mothers had either a primary school or university education. The authors speculated that the difference could be caused by higher employment outside the home by these mothers.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion as contextual factors for consideration are discussed in Chapter 3 (seafood consumption); Chapter 4 (nutrient intake from seafood), and Chapter 5 (exposure to contaminants in seafood). A summary of contextual factors relevant to assessing risks and benefits associated with seafood consumption is shown in Figure 7-3.

In summary, this chapter (1) discusses key gaps in the existing evidence, (2) proposes a three-step framework for conducting an RBA (Figures 7-1, 7-2, and 7-3), and (3) emphasizes the role of both individual- and community-level factors to consider when assessing risks and benefits associated with seafood consumption. The committee’s comprehensive approach suggests a “big data” strategy that could be enabled by artificial intelligence and machine learning methodologies to allow for predictive modeling informing prevention and early intervention action.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Findings

Approach to Conducting a Risk–Benefit Analysis

- The integration of diverse data sources and the heterogeneous nature of information available about risks and benefits presents a challenge when selecting metrics to adequately evaluate and compare these risks and benefits in a formal RBA. To date, many formal RBAs have focused on methylmercury as the contaminant and have not assessed contaminant mixtures and toxins. Many other contaminants present in mixtures showed gaps in evidence and hence were less suitable to conduct a formal RBA. Key factors influencing the conduct of RBAs include the social determinants of health at the individual level, such as poverty and health disparities, and cultural traditions and vulnerability at the community level.

Factors Influencing Risk–Benefit Analysis

- All 50 U.S. states issue voluntary fish consumption advisories on potential contaminant exposure from consuming local fish. Advisories often include specific information about contaminants found in distinct fish species and waters. The evidence available showed variability in the information included in fish advisories for how these hazards are described, and even more variability in what (or if) nutritional information is included in these advisories, yet they are an information source for consumers. A key focus was observed on risks associated with the consumption of MeHg-contaminated fish by pregnant women. Most advisories do not adequately address the risk for specific vulnerable populations, especially subsistence fishers. The committee finds that this irregularity across advisories makes comparison of risks and benefits difficult for most consumers.

Conclusions

- A risk–benefit analysis can be an excellent tool to analyze, in a transparent matter, factors that affect both benefits and risks in an integrated approach, rather than as independent domains. This integrated approach toward assessing benefits and risks positions an RBA to effectively support decision-making processes regarding fish consumption. This tool can be applied at the population and individual levels and its scope extended beyond health concerns by including costs, environmental sustainability, and ethics.

- The process for evaluating when or when not to conduct a formal RBA requires assessing the following four key areas: the state of evidence aided by systematic reviews of existing literature, the existence of validated approaches and metrics, an analysis of contextual factors affecting benefits or risk tailored to specific target populations, and the quality and uncertainty of the overall RBA evaluation.

- Formal risk–benefit analyses of fish consumption are seldom conducted because no comprehensive source exists that provides necessary, available data on consumption, contextualization factors, and contamination.

- Maximizing the usefulness of a risk–benefit analysis requires the integration of datasets addressing life stages, consumption patterns, information on nutrient status, exposure to contaminants, health outcomes, and contextual factors.

- Communication about potential health benefits conferred by specific nutrients in seafood is varied. The advisories reviewed by the committee were voluntary and not subject to regulation.

- Strengthening the links between a formal risk–benefit analysis, management decisions, and dietary recommendations communicated to the public can improve transparency and advance public health outcomes by ensuring that the best science informs management decisions.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 3: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration should consider conducting a risk–benefit analysis of maternal and child seafood intake and child growth and development, and, in doing so, routinely monitor data and scientific discoveries related to the underlying model and assumptions to ensure the assessment reflects the best available science.

Recommendation 4: In conducting a risk–benefit analysis, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency should include reviews of current evidence scans, systematic and supplemental reviews, approaches and metrics, benefit–harm characterization, and quality and assurance in evaluating the confidence in a risk–benefit analysis for policy decision making.

Recommendation 5: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, in collaboration with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, should create an integrated database to support risk–benefit analyses for fish consumption, thoroughly considering implications of using a metric that reflects transparency and conflicts of interest for both risk and benefit.

Recommendation 6: To maximize the use of a formal risk–benefit analysis, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in collaboration with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency should present conclusions of a risk–benefit analysis, including a risk estimate, in a readily understandable and useful form to risk managers and be made available to other risk assessors and interested parties.

RESEARCH GAPS

- Research is needed to inform the use of emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, to develop a comprehensive data integration framework to support the conduct of risk–benefit analyses.

- Research is needed to determine both the individual effect as well as the potential cumulative effects of factors that influence the conduct of a risk–benefit analysis.

- The science undergirding the conduct of a risk–benefit analysis should be periodically reviewed, such as every 3–5 years, and updated when needed.

REFERENCES

Andersen, L. F., P. Berstad, B. A. Bukhvalova, M. H. Carlsen, L. J. Dahl, A. Goksøyr, L. Sletting Jakobsen, H. K. Knutsen, I. Kvestad, and I. T. L. Lillegaard. 2022. Benefit and risk assessment of fish in the Norwegian diet—scientific opinion of the steering committee of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment.

Boué, G., S. Guillou, J.-P. Antignac, B. Le Bizec, and J.-M. Membré. 2015. Public health risk–benefit assessment associated with food consumption—A review. European Journal of Food Research & Review 5(1):32.

Boué, G., E. Ververis, A. Niforou, M. Federighi, S. M. Pires, M. Poulsen, S. T. Thomsen, and A. Naska. 2022. Risk–benefit assessment of foods: Development of a methodological framework for the harmonized selection of nutritional, microbiological, and toxicological components. Frontiers in Nutrition 9:951369.

Carrington, C. D., and M. P. Bolger. 2002. An exposure assessment for methylmercury from seafood for consumers in the United States. Risk Analysis 22(4):689-699.

Cohen, J. T., D. C. Bellinger, W. E. Connor, P. M. Kris-Etherton, R. S. Lawrence, D. A. Savitz, B. A. Shaywitz, S. M. Teutsch, and G. M. Gray. 2005. A quantitative risk–benefit analysis of changes in population fish consumption. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 29(4):325-334.

EFSA (European Food Safety Authority Scientific Committee). 2010. Guidance on human health risk–benefit assessment of food. EFSA Journal 8(7):1673.

EFSA. 2015. Statement on the benefits of fish/seafood consumption compared to the risks of methylmercury in fish/seafood. EFSA Journal 13(1):3982.

EFSA. 2017. Guidance on the use of the weight of evidence approach in scientific assessments. EFSA Journal 15(8).

EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain. 2012. Scientific Opinion on the risk for public health related to the presence of mercury and methylmercury in food. EFSA Journal 10(12):2985.

EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain. 2018. Risk for animal and human health related to the presence of dioxins and dioxin-like PCBs in feed and food. EFSA Journal 16(11: e05333.

FAO/WHO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation and World Health Organization). 2011. Report of the joint FAO/WHO expert consultation on the risks and benefits of fish consumption. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

FAO/WHO. 2023. Joint FAO/WHO expert consultation on the risks and benefits of fish consumption. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2014. Quantitative assessment of the net effects on fetal neurodevelopment from eating commercial fish (as measured by IQ and also by early age verbal development in children). https://www.fda.gov/food/environmental-contaminants-food/quantitative-assessment-net-effects-fetal-neurodevelopment-eating-commercialfish-measured-iq-and (accessed February 29, 2024).

FDA. 2017. FDA and EPA issue fish consumption advice. https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-and-epa-issue-fish-consumption-advice (accessed December 5, 2023).

Ginsberg, G. L., and B. F. Toal. 2009. Quantitative approach for incorporating methylmercury risks and omega-3 fatty acid benefits in developing species-specific fish consumption advice. Environmental Health Perspectives 117(2):267-275.

Ginsberg, G., B. Toal, and P. McCann. 2015. Updated risk/benefit analysis of fish consumption effects on neurodevelopment: Implications for setting advisories. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal 21(7):1810-1839.

Guenther, P. M., W. Juan, M. Lino, H. A. Hiza, T. V. Fungwe, and R. Lucas. 2009. Diet quality of low-income and higher-income Americans in 2003-2004 as measured by the Healthy Eating Index-2005. FASEB Journal 23:540.545.

Hanemaayer, R., H. T. Neufeld, K. Anderson, J. Haines, K. Gordon, K. R. L. Lickers, A. Xavier, L. Peach, and M. Peeters. 2022. Exploring the environmental determinants of food choice among Haudenosaunee female youth. BMC Public Health 22(1):1156.

Hoekstra, J., A. Hart, H. Owen, M. Zeilmaker, B. Bokkers, B. Thorgilsson, and H. Gunnlaugsdottir. 2013. Fish, contaminants and human health: Quantifying and weighing benefits and risks. Food and Chemical Toxicology 54:18-29.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2007. Seafood choices: Balancing benefits and risks. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Martínez-Martínez, M. I., A. Alegre-Martínez, and O. Cauli. 2020. Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids intake in children: The role of family-related social determinants. Nutrients 12(11).

Membré, J. M., S. S. Farakos, and M. Nauta. 2021. Risk-benefit analysis in food safety and nutrition. Current Opinion in Food Science 39:76-82.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine). 2023. Advancing health and resilience in the Gulf of Mexico region: A roadmap for progress. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27057.

Nauta, M. J., R. Andersen, K. Pilegaard, S. M. Pires, G. Ravn-Haren, I. Tetens, and M. Poulsen. 2018. Meeting the challenges in the development of risk-benefit assessment of foods. Trends in Food Science & Technology 76:90-100.

Scherer, A. C., A. Tsuchiya, L. R. Younglove, T. M. Burbacher, and E. M. Faustman. 2008. Comparative analysis of state fish consumption advisories targeting sensitive populations. Environmental Health Perspectives 116(12):1598-1606.

WCRF (World Cancer Research Fund) International. 2018. Meat, fish and dairy products and the risk of cancer. Continuous Update Project Expert Report. London, United Kingdom.