The Future of Youth Development: Building Systems and Strengthening Programs (2025)

Chapter: 8 Current OST Funding and Policies

8

Current OST Funding and Policies

Funding and policy decisions dictate the structural framework of out-of-school-time (OST) programs. Without sufficient funding and pertinent policies, even the most well-designed programs struggle to achieve their goals. In this chapter the committee considers the funding and policy mechanisms behind OST systems, settings, and programs, and what changes can be made in order to improve the availability, accessibility, and quality of OST programs serving children and youth from low-income and marginalized1 backgrounds. The sections that follow provide an overview of the key sources for OST funding: families, the public sector, and the private sector.

The chapter first discusses the role of program fees paid by families in supporting OST programs before moving to federal supports—including key funding streams and illustrative examples, cross-agency efforts, and other roles of government in extending capacity-building, evidence base, and research to advance the field forward. The committee then examines the role played by state policies and funding in shaping access to and opportunity in OST programs, including state implementation of federal funding streams, dedicated state funds for OST programs, state network efforts in technical assistance, professional development, and evaluation. This is followed by a brief discussion of local funding and support for OST programs.

___________________

1 In a scoping review of 50 years of research, Fluit et al. (2024) synthesized an integrated definition of marginalization as “a multifaceted concept referring to a context-dependent social process of ‘othering,’ where certain individuals or groups are systematically excluded based on societal norms and values, as well as the resulting experiences of disadvantage” (p. 1). The authors note that both the process and outcomes of marginalization can vary significantly across contexts (Fluit et al., 2024). See Box 1-3 in Chapter 1.

In addition to a description of the role of public investments, the chapter highlights philanthropy’s role in supporting OST programs, including efforts to fund innovation, frameworks and tools, and catalytic investments. Finally, the chapter outlines future directions for public and private investments in OST systems, settings, and programs.

Key Chapter Terms

21st Century Community Learning Centers (21st CCLC): The only federal funding stream dedicated to OST programs, the Nita M. Lowey 21st Century Community Learning Centers are a part of Title IV.B., administered through the U.S. Department of Education. It is awarded via funding formulas to state education agencies and then granted to local communities via a competitive process.

American Rescue Plan (ARP) funds: Emergency federal funds made available during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Blended funding: When two or more funding streams are merged to support one initiative. Many funders prohibit blending because it makes individual grant-reporting challenging.

Block grant: Federal funding awarded to state and local governments for a specific program (e.g., Child Care and Development Block Grants are awarded from the federal government to the state to support low-income families’ access to childcare for children under the age of 13).

Braided funding: When two or more funding streams are coordinated (but separate) to support one initiative (e.g., a program might utilize funding from Title I and their state’s afterschool investment to support OST activities).

Discretionary programs: Programs whose levels are appropriated by the legislative branch each year. The federal discretionary programs are competitive (e.g., Full-Service Community Schools represent an example of a discretionary grant by which the federal government reviews and selects applications across the country to fund selected initiatives).

Entitlement programs: Noncompetitive federal funds to support programs that are open to all eligible participants.

Formula grant: Also known as state-administered programs, formula grants are federal noncompetitive awarded to states using a predetermined formula. (e.g., 21st CCLC).

Full-service community schools: Schools that “improve the coordination, integration, accessibility, and effectiveness of services for children and families, particularly for children attending high-poverty schools, including high-poverty rural schools” (U.S. Department of Education [ED], 2024a, para 4).

Local workforce development board: A group of appointed officials who oversee and plan workforce services.

Municipality: A city or town with a local government.

State agencies: State education or childcare agencies.

State formula grants: Federal funds that are allocated to the states or local governments based on formula rather than competition.

PROGRAM FEES

Nationally, in diverse program models (including fee for service), many OST programs require fees for participation to cover operating costs (e.g., staff salaries and benefits, facilities).

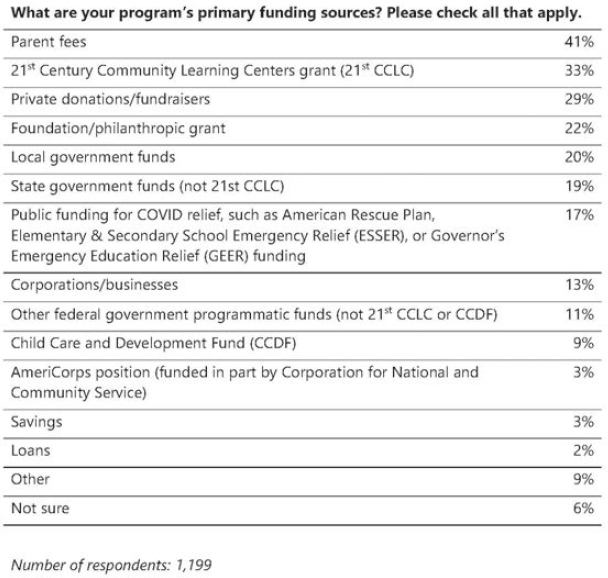

An online survey conducted in spring 2023 by Edge Research (Afterschool Alliance, 2023d), involving 1,119 OST providers that represent nearly 10,300 program sites in 50 states, showed that programs rely heavily on nonpublic funding sources, especially parent fees: 41% of providers reported parent fees as a primary funding source, the most common funding source cited. The other primary sources of funding were 21st Century Community Learning Centers (21st CCLC) grants, private donations and fundraisers, foundation and philanthropic grants, and local and state government funds. See Figure 8-1 for details.

SOURCE: Afterschool Alliance, 2023d, p. 37.

Primarily, this report examines OST programs serving children and youth from low-income households, where a goal is for public and private sources to alleviate the need for families to pay for participation. Still, some programs serving this population may charge fees and others may invite families to donate an amount they can afford—both instances can be a significant source of funding for these programs. Relying on family fees as a primary source of funding for OST participation is a likely contributor to the differential access to programs between families with low and high incomes. As noted in Chapter 4, families with low incomes often cite program costs as a factor in their decision not to enroll their child. Some programs have implemented policies to reduce or eliminate fees for these families, such as sliding pay scales based on family income; scholarships; stipends for older youth to participate; and, where possible, making program participation free.

PUBLIC FUNDING AND POLICIES

It is challenging to quantify all the public funding dedicated for OST systems, settings, and programs because many of the public funding streams have a wide variety of allowable uses and do not report on how much of the funding is directed to OST programs specifically. In addition, nearly all the public funding sources support a combination of OST experiences (e.g., afterschool and summer programs). The total funding across the most commonly reported public funding sources that are directed specifically to OST programs primarily serving children and youth from low-income households is roughly $6.3 billion annually: $5 billion from state funding streams and $1.3 billion from 21st CCLC grants. Using a conservative estimate of the cost of providing high-quality programming, at $2,400 per participant per year, that $6.3 billion reaches approximately 2.6 million young people (consistent with the most recent count of 2.7 million children and youth from low-income households who participate in OST programs [Afterschool Alliance, 2020]). This number is far outpaced by demand, as the America After 3PM (AA3) survey2 reports: approximately 24.6 million children and youth would participate if programs were available (Afterschool Alliance, 2020), including more than 11 million from low-income households (Afterschool Alliance, 2024c). Furthermore, because of lack of public data on the overall direct spending on OST across all public funding streams, coupled with a lack of disaggregated data by demographic variables, it is unclear how many eligible students, such as those attending Title I schools, have access to quality OST programs.

___________________

2 The AA3 survey assesses participation across all OST programs serving all children and youth, not only programs serving those from low-income households. In the most recent AA3 study from 2020, over 30,000 households were surveyed with questions about the ways in which their child or children are cared for in the hours after school, participation in organized activities and summer experiences, and household demographics. Survey results are examined in Chapter 4.

Federal Funding for OST

The primary role of the federal government in the youth development field is to provide guidance, funding, and assistance to address national issues, while leaving the majority of funding decisions to state and local control (Jennings, 2015).3 This section first addresses the federal funding landscape, offering an overview of some of the notable OST-related funding streams under several agencies, including those that are focused on OST or could be used to support OST; it then notes the role of the government as it pertains to research, technical assistance, and emergency relief.

Similar to funding for K–12 education historically, federal funding represents only a small fraction of the overall funding for OST opportunities, with estimates of 10% of all K–12 education funding and 11% of OST funding coming from federal sources (Afterschool Alliance, 2009; Children’s Funding Project, 2023b). Yet, those funds play an important role, especially when it comes to reaching children and youth from low-income backgrounds. Issues pertaining to youth development have often been distributed to different areas based on their primary designation (e.g., health, education, housing, food), leading to a siloed approach to OST funding; this funding is currently spread across 25 federal agencies and departments.4

The federal government administers over 280 programs supporting children and youth, the majority designed to support low-income families (Afterschool Alliance, n.d.a; Children’s Funding Project, 2023b). Of those, 87 are designed to support OST programs in direct or indirect ways (Children’s Funding Project, 2023b).5 Of note, the American Rescue Plan (ARP); the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act of 2020; and the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations (CRRSA) Act of 2020 contained provisions that benefited OST providers (this COVID-era relief funding is discussed in detail in Box 8-1 and Appendix B). Although the breadth of funding streams available offers a variety of opportunities for support, each funding stream has limitations in depth of reach. Only a few eligible programs receive funding either directly or through a partnership with a district, city/county, or a university,

___________________

3 For a primer on federal government and the Congressional appropriations process, please visit https://www.congress.gov/legislative-process

4 The U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Education and the Workforce and its associated Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education handle legislation on the OST system and programs. The U.S. Senate’s Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee and its subcommittee on Children and Families hears OST-related bills. Committees that deal with OST-related appropriations include the House of Representatives’ Labor, Health, Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Committee and the Senate’s Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies.

5 The Children’s Funding Project tracks federal funding investments in child and youth services through an interactive map. For more information see https://www.childrensfundingproject.org/federal-funding-streams

BOX 8-1

Federal Pandemic-Related Relief Funds Supporting OST Programs

The American Rescue Plan (ARP) was the third and final in a series of COVID-19 relief packages intended to spur recovery from the devastating effects of the pandemic. While the two previous relief packages, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act of 2020 and the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations (CRRSA) Act of 2020, contained provisions that benefited out-of-school-time (OST) providers, ARP offered the greatest funding opportunity and most explicit language regarding use of funds for afterschool and summer opportunities.

In total, the ARP provided up to $500 billion that could be used to support young people during the hours they are out of school. Estimates suggest that at least $10 billion of that supported afterschool and summer opportunities (Afterschool Alliance, 2023a). It is important to note, however, that all of the ARP funds were time limited. States, schools, and communities that directed ARP funds to support OST opportunities must find alternate funding streams to support their initiatives. These changes may happen as early as September 2024 and no later than March 2026 (Roza & Silberstein, 2023). Throughout 2023 and 2024, numerous states initiated new or increased existing state funding streams for OST in an effort to help minimize the impact of expiring ARP funds on families and youth. (See Appendix B for more detail on ARP investments.)

SOURCE: Generated by the committee, with excerpts from Afterschool Alliance, 2023a; Roza & Silberstein, 2023.

leaving some children and youth from low-income backgrounds without adequate access to OST opportunities.

The following sections describe the most prevalent funding associated with this committee’s task, highlighting nine agencies that administer significant OST programming for children and youth from marginalized backgrounds.6 The overview offers an illustration of opportunities for OST program support, but also underscores the fragmented nature of the overall federal funding landscape for youth development.

U.S. Department of Education OST Programs

The U.S. Department of Education (ED), under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA; the reauthorized Elementary and Secondary Education Act [ESEA]), administers multiple OST-related grants, including in Titles I,

___________________

6 A full list of OST programming administered by federal agencies can be found at youth.gov.

II, and IV. 7 In addition to CCLCs, it administers the Full-Service Community Schools grant, which incentivizes partnerships between local education agencies and OST providers, and Promise Neighborhoods, which embrace comprehensive, whole-child, whole-community strategies. The sections that follow provide an overview of these investments.

21st Century Community Learning Centers

is the only dedicated funding stream for OST programs at the federal level; it grew from $750,000 in 1995, to $1 billion in 2001, to $1.3 billion in 2024 (Afterschool Alliance, 2023b; McCallion, 2003). While $1.3 billion is a sizable investment, it represents a fraction of the overall federal funding for education, which totals roughly $79.1 billion (Committee for Educational Funding, 2024). Moreover, that investment reaches only a small segment of the overall K–12 population in the United States. In 2023, nearly 1.4 million students benefited from 21st CCLC (Afterschool Alliance, 2023b). However, compared with 49.6 million public school students in the country (National Center for Education Statistics, 2023), this investment reaches only 3% of the total public school student population.

21st CCLC legislation was first introduced in 1994, attached to the Improving America’s Schools Act of 1994, the ESEA Reauthorization, Title IX, Part I. Authorized through 1999, the program was focused on developing community schools, promoting 21st-century learning, and encouraging school–community partnerships, with school districts being the primary recipients (McCallion, 2003, 2008). The allowable use of funds included activities such as OST programming, extended library services, nutrition and health programs, family engagement, senior citizen programming, and services for individuals with disabilities. With the brokered partnership between ED and the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, 21st CCLC benefited from strong public and philanthropic partnership, bipartisan support, and the federal budget surplus of the late 1990s. The funding stream grew substantially from $750,000 in 1995 to $845.6 million by 2001 (Phillips, 2010). By then, there were 308 awardees among 2,850 applicants, signaling an unmet demand for federal support for OST programs (Gayl, 2004).

The ESEA reauthorization, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2002, evolved 21st CCLC to an additional $250 million per year for 6 years, growing the authorized levels between 2002 and 2007 to $2.5 billion. However, the appropriations allocated approximately $1 billion per year, leaving a gap between the allowable and authorized amounts. The competitive grants

___________________

7 The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (now known as the Every Student Succeeds Act) focused attention on ameliorating pernicious gaps in opportunities and learning outcomes for various populations of learners, whether through bilingual education, students with disabilities, or students from low-income backgrounds (Cross, 2014).

shifted from federal allocation to state formula grants, based on Title I-A funding from the previous year (Congressional Research Service [CRS], 2003). This was a significant shift from prior grant administration that shifted control to the states. The grant length was 3–5 years, and eligibility expanded to be inclusive of community- and faith-based organizations (McCallion, 2003). The grant focused on three priorities:

- Provide academic enrichment to meet state and local student achievement standards in core academic subjects,

- Offer a broad array of additional activities designed to reinforce and complement regular academic programming, and

- Offer families of students with opportunities for literacy and related educational development (ED, 2024b, para. 1).

As a result, 21st CCLC prioritized academic achievement and student support such as tutoring, mentoring, homework assistance, library and counseling services, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) programs, career readiness, and family engagement, among others (CRS, 2003). In 2002, two-thirds of the awardees served elementary school students primarily and one-third served middle school students primarily; 15% served high school students and 5% targeted secondary education students.

In 2015, the Nita M. Lowey 21st CCLC program was reauthorized through ESSA as part of Title IV, Part B. Its three priorities are

- Academic enrichment, including tutoring for students in low-performing schools;

- A broad array of youth development activities; and

- Family engagement.

The 2015 reauthorization signaled evolution of the program to focus on whole-child supports, family engagement and literacy, and supporting students with disabilities and English-language learners. In addition to reading and math, 21st CCLC can offer programming in STEM, arts, health, and music, and maintain the long-standing drug and violence prevention focus (Afterschool Alliance, 2023b). Students have an opportunity to engage in educational development, mentoring, internship, apprenticeships, and career readiness.

Today, 21st CCLC are funded at $1.3 billion, with 85% of the funded programs reported to support academics, STEM, physical activity, and peer-to-peer relationships (Afterschool Alliance, 2023b). The federal funding is administered through states, allowing states to establish funding competitions, professional development and technical assistance, evaluation, and guidance. Each 21st CCLC involves hiring and extensive coordination with schools and partnerships with community-based programs. In summer 2023,

ED drafted nonregulatory guidance for the program to align 21st CCLC with the 2015 legislative language, with attention to blending and braiding of funds;8 access and equity in underserved areas; investments in research and practice for high-quality programming; and intentional engagement of youth, family, and community voices (Afterschool Alliance, 2023c).

Full-Service Community Schools

ED (2024a) also administers the Full-Service Community Schools (FSCS) grant, reaching 292 schools and 229,549 students.8 The FSCS funding stream “provides support for the planning, implementation, and operation of full-service community schools that improve the coordination, integration, accessibility, and effectiveness of services for children and families, particularly for children attending high-poverty schools, including high-poverty rural schools” (ED, 2024a, para. 4). In fiscal year 2022, significant investments were made in the FSCS strategy, propelling the funding to $75 million and doubling to $150 million in fiscal year 2023 (ED, 2024a). FSCS is guided by four pillars: integrated supports, expanded learning opportunities, family and community engagement, and collaborative leadership (ED, 2024a). OST programs are an important part of FSCS expanded learning opportunities and can include programs such as homework assistance and tutoring, academic programs, mentoring, youth development programs, community and service learning, and job training (Maddox, 2024).

Promise Neighborhoods

were authorized under the ESEA of 1965, which was amended by ESSA in 2015. Their purpose is to “significantly improve the academic and developmental outcomes of children living in the most distressed communities of the United States, including ensuring school readiness, high school graduation, and access to a community-based continuum of high-quality services” (Office of Elementary & Secondary Education, 2024, para. 1).9 Eligible organizations for a Promise Neighborhood grant include higher education institutions, nonprofit organizations, and tribal organizations (ED, 2022). Between 2010 and 2023, 39 Promise Neighborhoods worked with 348,474 children in 321 schools in several states, including California, Texas, Minnesota, and New Jersey (ED, 2023a).

___________________

8 The historical investment in the community schools strategy by the federal government dates back to the 1974 Community Schools Act and the 1978 Community and Comprehensive Community Education Act (Edelman & Radin, 1991; Fantini, 1983). In fiscal year 2009, roughly $5 million in FSCS funding was authorized as allowable use of funds under ESEA Title V, Part D, Subpart 1, Fund for Improvement of Education, as a competitive demonstration program. Throughout fiscal years 2010–2015, the program received $10 million in annual funding (ED, 2024a) and continued to grow modestly from 2015 to 2021, from $17.5 million to $30 million, respectively.

9 The program builds from the success of the Harlem Children’s Zone, supporting efforts to scale the model to other neighborhoods and localities (Croft & Whitehurst, 2010).

Between 2010 and 2021, ED (2022) awarded 82 planning, implementation, and extension grants to several nonprofit organizations and higher education institutions (see also Office of Elementary & Secondary Education, 2023a). Promise Neighborhoods grantees are required to report 10 outcomes that span a cradle-to-career pipeline: school readiness, academic proficiency, successful transitions, high school graduation, college and career ready, healthy students, safe communities, stable communities, supportive communities, and 21st-century learning tools (ED, 2023b). OST programs are an important component of this holistic strategy.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) administers two key family assistance programs: the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

The Child Care and Development Fund

is part of the Child Care and Development Block Grant Act enacted in 1990 (and amended in 1996 and 2014) and funded through capped entitlement grants and discretionary funding (CRS, 2003). It offers $9.5 billion for childcare subsidies to low-income families administered through states, tribes, and territories (HHS, n.d.a,b). OST programs are supported through either direct provider contracts or vouchers to families. The amounts are driven by individual jurisdictions, with each state determining its associated policies, services, and quality improvement of eligible services. (State examples are offered in the following section on state-level policies and funding.) Although 45% of children served by CCDF subsidies are of school age, there is no guarantee of equivalency of the same percentage of funding for OST programs for school-age children, as school-age subsidies are considerably lower than early care subsidies (National Center on Afterschool and Summer Enrichment, 2022).

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

provides financial assistance for childcare to low-income families, which offers $16.5 billion of annual funding to the states and territories to provide cash assistance for low-income families that can be used toward OST program fees and family labor market entrance and persistence (HHS, n.d.b; 2018). TANF can be used for OST programs directly, and their use offers a wide range of services. Thirty percent of these TANF funds can also be transferred to CCDF to expand OST programming. The most recent Notice of Proposed Rulemaking will further adjust costs for inflation, define the term needy, and ensure use of funds as intended by the law, including for OST programs and childcare services (Strengthening Temporary Assistance for Needy Families [TANF] as a Safety Net and Work Program, 2023).

U.S. Department of Justice

The U.S. Department of Justice Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) supports mentoring programs in OST through competitive discretionary grants focused on supporting youth at risk of being court involved as well as court-involved youth (ages 12–21, with some transition-age programs supporting youth through age 24). Its Multistate Mentoring Program Initiative is one illustrative example of multiyear investment in nationwide mentoring efforts to promote career exploration, workforce development, and employment through mentoring in OST (OJJDP, 2021). OJJDP (2023) also administers the Youth Violence Prevention Program with a focus on gang/group violence prevention through referrals to service systems and youth programming.

In addition to the programs focused on youth who face risks for engaging with the justice system, OJJDP also administers programs for youth through the Juvenile Justice Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA), which addresses juvenile delinquency through evidence-based prevention programs and practices, mental and behavioral health supports, and positive youth development for youth within the juvenile justice system. JJDPA supports state, local, and tribal government programs for youth within restrictive settings (OJJDP, 2018; Snodgrass Rangel et al., 2020); it offers technical assistance, training, evidence-based research and evaluation, and broad dissemination of evidence-based research to improve outcomes for youth involved in the juvenile justice system. To receive funding, each state must submit a plan, which in part details positive youth development programs.10 OJJDP compliance measures are focused primarily on factors such as deinstitutionalization, separating adults and juveniles in facilities, and racial/ethnic disparities within the juvenile justice system.

U.S. Department of Agriculture

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Division of Youth & 4-H administers the 4-H program. 4-H “serves as a model program for the practice of positive youth development by creating positive learning experiences; positive relationships for and between youth and adults; positive, safe environments; and opportunities for positive risk taking” and is conducted through the land-grant university extension 4-H offices (National Institute of Food and Agriculture, n.d., para 3). 4-H serves 6 million children and youth ages 9–17 annually, through

___________________

10 Within the legislation, positive youth development programs are defined as “programs [that] assist delinquent and other at-risk youth in obtaining— (i) a sense of safety and structure; (ii) a sense of belonging and membership; (iii) a sense of self-worth and social contribution; (iv) a sense of independence and control over one’s life; and (v) a sense of closeness in interpersonal relationships” (JJDPA, 34 U.S.C. § 1133[a][9][4]).

STEM, agricultural sciences, leadership, and career development programming. The National 4-H Council supports programming of 4-H sites.

In addition to youth programming through 4-H, USDA plays a critical role in supporting conditions for child and youth development in the form of food security benefits that support families at school, in OST spaces, and during the summer. Child nutrition programs support both in-school and out-of-school child nutrition and include the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program (SBP), and Summer Food Service Program. SBP reimburses states that operate nonprofit breakfast programs, including before-school OST programs, serving 15 million students (USDA, n.d.).

According to USDA (2024), only one in six eligible students access summer meal programs. To increase participation, the Summer Nutrition Programs for Kids now offers rural community delivery, group meal sites, and food benefits at local grocery stores. The meals can also be administered in partnership with summer OST programs for eligible students. The Summer EBT program (SUN Bucks) is federally funded and supports OST programs; in 2024, this program is administered by 36 state agencies and 9 territories and tribal nations and their local partners to reach families (USDA, 2024).

U.S. Department of Labor

Through the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL, n.d.) administers three long-standing OST-connected programs: Job Corps, Youth Activities, and YouthBuild.

Job Corps,

founded in 1964, helps young people ages 16–24 connect to workforce opportunities through job training, service learning, career and technical education, and academic supports in 123 centers (CRS, 2020, 2022). Its programs expose youth to over 70 careers as they work toward secondary and postsecondary credentials. With around 50,000 participants, Job Corps enables federal, state, and local agencies, and nonprofit organizations to contract with DOL to run these learning opportunities (CRS, 2020, 2022).

Youth Activities,

a formula grant program within WIOA, supports OST learning for youth ages 14–24 with particular attention to youth from low-income backgrounds (CRS, 2022). The funding serves up to 15 statewide efforts; remaining funds go to local workforce development board activities designed to support local partnerships with community-based organizations and community colleges (Collins & Edgerton, 2022). The OST programs served through Youth Activities include 14 program elements,

such as tutoring, internships, preapprenticeships, and summer employment. In 2020–2021, this program served 123,000 youth (CRS, 2022).

YouthBuild

is a competitive award program, funded through WIOA, that is designed to support annually approximately 6,000 youth ages 16–24 in on-the-job skill training and leadership skills (CRS, 2020). Youth who can be served through this program include those who come from low-income backgrounds, are in foster care, have been formerly incarcerated, are from migrant families, or have disabilities. YouthBuild focuses on three elements—construction, education, and leadership training. Research shows that participants are more likely than their peers to obtain GEDs, enroll in college, and increase earnings (CRS, 2020).

U.S. Department of Defense

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) administers education programs for military families on bases across the country and the globe. In fact, “DoD operates one of the largest employer-sponsored child care programs in the U.S., serving more than 160,000 children every year” (Clark, 2024, para. 12). DoD’s (n.d.) School Age Centers (SACs) are OST programs that serve children ages 6–12 and can partner with such entities as 4-H and Boys & Girls Clubs of America. They include full-day, before-school, afterschool, and seasonal programs, guided by the National AfterSchool Association framework. SACs focus on “leisure, recreation, and the arts; sports and fitness; life skills, citizenship, and leadership; and mentoring and supporting services” (U.S. Army, n.d., para 1). To support low-income families, the SAC rate schedule is determined based on total family income, ranging from $54 to $138 for a basic weekly rate (Clark, 2024). Additionally, a cooperative agreement established the Defense Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Education Consortium to provide STEM programming supporting workforce development needs through hands-on and side-by-side learning opportunities for students over the upcoming decade (DoD, 2024).

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (n.d.) administers the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) for states, counties (under population of 200,000), and cities (under population of 50,000), focusing on housing, economic development, and support of low-income families and individuals. Started in 1974 under Title I of the Housing and Community Development Act, the CDBG supports cross-governmental partnerships, including enabling local governments to revitalize community centers and OST programs.

AmeriCorps VISTA

As mentioned in Chapter 3, AmeriCorps (n.d.b) is the federal agency focused on national service and volunteerism. About 7,000 AmeriCorps members participate in the Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) program, which supports OST programs annually (AmeriCorps, n.d.a). They are categorized as members, leaders, and summer associates. In exchange for service, AmeriCorps offers support for housing, money for postsecondary education, and ongoing training. Those who serve through AmeriCorps (n.d.a) are eligible for loan deferment and interest forbearance. VISTA volunteers offer an important source of staff in OST programs.

National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation (NSF) has a long-standing commitment to building the evidence base in STEM programming, helping build the future STEM workforce, and creating opportunities in STEM learning for students from low-income backgrounds. Two funding streams offer opportunities for programmatic evaluation and knowledge development and sharing to advance the scientific and OST communities: (1) Advancing Informal STEM Learning funds OST STEM programs and advances research and assessment of such programs (NSF, n.d.b), and (2) the Innovative Technology Experiences for Students and Teachers (ITEST) supports young people in grades K–12 in STEM learning about information and communications technology. ITEST is designed to support STEM career pathways through interdisciplinary work, including mentorship, career exploration, and preparation programs (NSF, n.d.a).

Other Roles of the Federal Government

In addition to providing funding to support OST programs, the federal government plays other important roles, such as coordinating cross-agency efforts, providing technical assistance, funding research and clearinghouses, issuing timed initiatives on cross-cutting issues central to an administration, and supporting state and local governments in critical situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

A number of efforts exist across federal agencies and through public–private partnerships to coordinate across the various funding streams described below. For example, the Interagency Working Group on Youth Programs (IWGYP) was formed in 2008 and comprises 12 federal agencies and 13 federal departments (see youth.gov, n.d.). IWGYP runs the youth. gov website that lists federal funding streams available for OST programs,

alongside seminal toolkits, guides, frameworks, and analyses that inform the field. IWGYP also manages a youth-focused leadership effort, Youth Engaged 4 Change (n.d.), a program geared toward 16- to 24-year-old youth who are leading change in their communities, regionally, and/or nationally.

ED and the Johns Hopkins Everyone Graduates Center collaborate to support the National Partnership for Student Success (NPSS), a cross-government and cross-sector collaboration to support student learning through wraparound supports, coaches, mentors, tutors, and postsecondary transition coaches. NPSS (n.d.) offers technical assistance, resources, and convenings for districts, states, and OST providers; develops and disseminates quality standards; conducts research; disseminates information; and collaborates with AmeriCorps for volunteer placement.11

The federal government also funds technical assistance through awards and contracts to entities such as intermediaries, research institutions, higher education institutions, small businesses, and others, to offer capacity-building and support to grantees and the broader field. For instance, the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance funds 10 Regional Educational Laboratory Programs (RELs) that work with local and state entities (e.g., school districts, state education agencies) to inform policy, research, and practice (IES, n.d.a). RELs broadly offer support on a range of education issues, and they can provide support to the OST field through evaluation toolkits, research guidance, and related assistance. HHS’s Office of Child Care, Child Care Technical Assistance Network offers training and technical assistance under the National Center on Afterschool and Summer Enrichment to Child Care and Development Fund lead agencies, supporting areas such as coordination of early child care and OST, and quality school-age child care (NCASE, n.d.).

Funding research is critically important to advancing the youth development field and a key role for the federal government. The federal government can support research in various ways, such as continued funding of agencies and associated clearinghouses, authorized use of funds toward evidence-generating activities, and set-aside allocations that require federal grantees to budget for internal and/or external evaluations (Executive Office of the President Council of Economic Advisers, 2014). For example, designated funding has allowed the IES (n.d.b) to run an ongoing evaluation of 21st CCLC. In addition, grantees are required to set aside funds for ongoing program monitoring and evaluation to assess progress and report on government performance

___________________

11 NPSS closed in January 2025 and will continue as the Partnership for Student Success. For more information see https://www.partnershipstudentsuccess.org

indicators. The 21st CCLC evaluation requirement “has created incentives for evaluating afterschool programs and has therefore shaped afterschool evaluation in a number of ways” (Weiss, 2013, p. 3). In addition, IES (2009) published a guide to help schools, districts, and OST programs increase student learning. The guide, which informs research and evaluation in the youth development field, recommends that “OST programs design features that ultimately strengthen academic progress while fulfilling the needs of parents and students” and “deliver academic instruction in a way that responds to each student’s needs and engages them in learning” (IES, 2009, pp. 8–9). The evaluation guidance does not offer direct caps on evaluation costs but offers parameters for the allowable use of funds.

Federal clearinghouses are another access point to OST research. The Safer Schools and Campuses Best Practices Clearinghouse offers evidence on academic excellence, improved learning conditions, and pathways for global engagement (ED, 2024c). It offers resources, technical assistance, illustrative examples, and learning events. Additionally, the Youth.gov Evidence for Program Improvement (EPI) offers an approach to evidence-based OST practices. EPI is organized across three main domains: externalizing behavior, social competence, and self-regulation, each with areas of inquiry (e.g., academic-educational, relational, and skill-building interventions). EPI offers a clearinghouse of evidence-based programs and core components approaches. Other agencies have their own evidence-based clearinghouses for youth programs: the AmeriCorps Evidence Exchange,12 Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Model Programs Guide,13 and Clearinghouse for Labor Evaluation and Research.14

The federal government also engages in special initiatives, such as public–private partnerships to provide schools and communities the connections and assistance they may need to expand access to afterschool and summer learning programs.

And finally, the federal government at times provides special funding opportunities in emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Enacted in March 2021, the ARP provided a total of nearly $122 billion in Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds to states and school districts to address the impact of the pandemic on schools and students. ARP outlined specific ways in which state and local education agencies should use their ARP ESSER funds to provide OST opportunities for young people. Of the roughly $12.2 billion in ARP ESSER funds available at the

___________________

12 https://americorps.gov/about/our-impact/evidence-exchange

state education agency level, states were directed to reserve the following to support OST programs:

- $1.22 billion for summer enrichment (1%)

- $1.22 billion for evidence-based comprehensive afterschool programs (1%)

- $6.1 billion, for learning recovery, such as summer learning or summer enrichment, extended day, comprehensive afterschool programs, or extended school year programs (5%)

Of the $109 billion in ARP ESSER available at the local education agency level, districts were required to reserve 20% ($22 billion) for learning recovery strategies, including afterschool and summer enrichment. If a district decided their OST funding needs were greater than their learning recovery set-aside, there was nothing in the legislation that prohibited a district from spending more than 20%; however, given the wide range of needs at the district level, that is widely seen as an unlikely.

State-Level Funding and Policies Shaping OST

Since 2000, state-level investment in OST programming has grown more than 20-fold, from a total of $264 million in 15 states in 2020 to $5 billion in 26 states in 2024 (Afterschool Alliance, 2024b). California has consistently topped the list of state investments and currently accounts for more than $4 billion of the total investment by states. In 2024, five new states (Colorado, Hawaii, Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Virginia) began investing in afterschool and summer, totaling $47 million (Neitzey, 2025). The importance of state policy in closing opportunity gaps in access to OST opportunities for youth cannot be overstated.

As mentioned in Box 8-1, the expiration of COVID-19 relief funds for OST programs presents states with an urgent reason to dedicate funds in this area. One way that states are approaching funding for OST programs is using dedicated line items in state budgets. A number of states have amplified their efforts to secure new funding streams or maximize existing funding streams to support afterschool, and often summer, opportunities for youth. In 2023 and 2024 alone, 10 states offered new funding to support OST programs, many of which were specifically cited as intended to help sustain ARP ESSER–funded programs (see Table 8-1). Box 8-2 details examples of how states are securing dedicated funding for OST programs.

States also fund OST through state revenues. One recent approach is using tax revenue from adult-use cannabis sales to support OST. As of early 2024, eight states that have legalized adult use of cannabis are directing some tax revenues from those sales to youth development, including OST

| State | Year | Funding Amount | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hawaii | 2024 | $20 million | State funding for summer learning and enrichment programs for summer 2025 to help sustain programs supported through the ARP ESSER funds. |

| Minnesota | 2023 | $30 million | $7.5 million annually over 4 years (totally $30 million) for the Afterschool Community Learning Grant to help sustain programs supported through the ARP ESSER funds. |

| Michigan | 2023 | $50 million, increased to $75 million in 2024 | Funding for comprehensive afterschool and summer programs, with 60% of funding dedicated to community-based organizations (CBOs) to help sustain programs supported through the ARP ESSER funds. |

| Missouri | 2024 | $7.4 million | New investment in comprehensive afterschool programs. |

| New Mexico | 2023 | $20 million in 2023, $15 million in 2024 | $20 million in 2023–2024 to help sustain programs supported through ARP ESSER funds. $15 million in 2024–2025 for afterschool programs, of which $8.5 million is designated for tutoring. |

| Oregon | 2024 | $30 million | New state funding for summer learning and enrichment programs offered by school districts in partnership with CBOs. |

| Pennsylvania | 2024 | $11.5 million | Funding for afterschool programs and summer enrichment with a focus on reducing community violence. |

| Texas | 2023 | $5 million | $5 million over 2 years for CBOs to offer OST programs with a focus on supporting youth mental well-being. |

| Vermont | 2024 | $4 million | $4 million per year for afterschool and summer programs (funded in part by cannabis sales tax revenue). |

| Virginia | 2024 | $5 million | $5 million over the next 2 years for afterschool and summer enrichment programs to help sustain programs supported by ARP ESSER funds. |

NOTE: ARP ESSER = American Rescue Plan Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief.

SOURCE: Data from Afterschool Alliance, 2024b.

BOX 8-2

Examples of Securing Dedicated State-Level Funding for OST

Securing dedicated state funding for out-of-school-time (OST) opportunities often takes a number of years and the express support of governors and state legislatures, as evidenced by Vermont’s journey toward state funding for afterschool programming. In 2016, after years of administering 21st Century Community Learning Centers grants in the state and building an infrastructure to support quality OST programs, the Vermont Child Poverty Council, a subcommittee of the Vermont state legislature, recommended funding for afterschool and summer learning as a top priority. Shortly after, in 2018, $600,000 in state tobacco settlement funds were directed to OST programs—the first state investment in programs (Vermont Afterschool, 2019, 2020). In 2020, Vermont’s governor pledged to provide universal afterschool programming for Vermont’s students. Since that time, the state leveraged federal COVID-19 relief funds to expand afterschool and summer programming, and in 2024, the state announced the availability of $3.5 million in afterschool grants (State of Vermont Agency of Education, n.d.).

Similarly, California’s Proposition 49 is the most well-known ballot initiative supporting expansion of OST programs (Afterschool Alliance, n.d.c), leading to the first statewide investment in afterschool in 2002, and the funding has grown and expanded over time. Additionally, in 2023, even as the state faced a projected budget deficit, it proposed continued funding for the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program at $4.4 billion and outlined a goal of growing the state funding stream to $5 billion in the coming years (California Afterschool Network, 2024).

In Virginia, an amendment to the state budget was introduced in 2023 directing the state education agency to study the availability of OST programs, identify gaps in access, and develop recommendations to help more families access programs. The study would also include identifying the benefits provided by OST programs and potential funding sources (Virginia General Assembly, 2023).

The Council of the District of Columbia (2023) introduced the Out of School Time Special Education Inclusion and Standards Amendment Act of 2023. It directed the Office of Out of School Time Grants and Youth Outcomes, in coordination with the Office of the State Superintendent of Education, to develop standards for training and recruiting OST providers for students with individualized education programs (IEPs). The agencies are also directed to undertake a study to determine the financing needed for attracting and retaining OST practitioners who are qualified to provide OST programming for students with IEPs.

In 2021, Oklahoma House Bill 1882 created the Oklahoma Out-of-School Time Task Force (2022) to study the return on investments of OST programs across the state, resulting in recommendations for the establishment of a sustainable OST funding source, including equitable access to funding for community-based organization providers, standardized outcomes and reporting, and training and technical assistance related to data collection.

programs. There is no documented tracking of how much cannabis tax revenue is directed to OST programs, but some estimate as much as $500 million per year (Afterschool Alliance, n.d.e).

In addition to cannabis tax revenue, states fund OST programs using other revenue sources, such as lotteries, license plate fees, public settlements, and taxes on sports betting and digital advertising (Illinois Secretary of State, n.d.; see Table 8-2).

TABLE 8-2 State Revenue Sources Directed to Out-of-School-Time (OST) Programs

| Adult-Use Cannabis Tax Revenue | |

| Alaska | The state legislature created the Marijuana Education and Treatment Fund in 2018. The legislation mandated that 25% of all cannabis tax revenue be deposited into the Fund and then split between the Positive Youth Development Afterschool Program—which supports afterschool, evening, and weekend programs that serve children in grades 5–8—and the Department of Health & Social Services for education, treatment, surveillance, and monitoring of marijuana. The legislation also explicitly mentions professional development, which allows for supporting and training OST staff on quality practices. As of 2024, the funding totals $2 million, and nine OST providers in Alaska received funding in 2023 (Alaska Afterschool Network, n.d.). |

| Illinois | The Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act of 2019 created the Restore, Reinvest, and Renew (R3) grant program, which targets areas with high economic disinvestment, gun violence, unemployment, child poverty, and rates of incarceration, as well as those disproportionately impacted by previous drug convictions. It calls for using 25% of all cannabis tax revenue to help tackle some of the challenges in these targeted communities. In 2021, the first grants totaled $31.5 million, half of which funded youth development initiatives. In 2022, $45 million in grants were awarded (Office of the Lieutenant Governor, 2023). |

| New York | The Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act of March 2021 dedicated 40% of all cannabis tax revenue to community reinvestment, with a focus on communities disproportionately impacted by previous cannabis-related convictions. The Community Grants Reinvestment Fund provides grants to nonprofits and local governments and includes OST programs as an allowable use of funds (Afterschool Alliance, 2022a). |

| Unclaimed Lottery Funds | |

| Nebraska | Nebraska has been directing a portion of unclaimed lottery funds to OST since 2016. |

| Tennessee | Tennessee’s Lottery for Education: Afterschool Programs was created in 2002 to direct unclaimed lottery funds for public and nonprofit OST programs serving participants aged 5–18, with priority for programs enrolling 80% high-need students (Tennessee Lottery for Education Amendment, Tenn. Const. art. XI, § 5 [2002]). |

| Settlement Funds | |

| Colorado | The Colorado Opioid Abatement Council provided $500,000 infrastructure grants to the Boys & Girls Clubs in Fremont County and Chaffee County to support facilities expansion and development, which enabled them to expand their OST offerings (Colorado Office of Attorney General, n.d.). |

| Vermont | The earliest example of settlement funds for OST comes from Vermont’s use of funds from the tobacco industry’s Master Settlement Agreement. Vermont’s Afterschool for All Grants started with a one-time tobacco settlement funds allocation of $600,000 by the Vermont Legislature to Vermont’s Child Development Division in 2018 to increase access to OST learning programs. Twelve OST efforts received funding for 2 years (Vermont Afterschool, 2020). |

| Wisconsin | In 2023, Wisconsin dedicated $750,000 of its $31 million in opioid settlement funding to the Boys & Girls Club of Fox Valley to partner with the Wisconsin Alliance of Boys & Girls Clubs and 25 other Boys & Girls Clubs organizations to serve children and youth at 199 sites in 73 communities across the state. Its SMART Moves Program provides children and youth with the information and skills to make healthy decisions (Wisconsin Department of Health Services, 2024). |

| License Plate Fees | |

| Illinois | Illinois’s Park District Youth Program directs license plate fees to OST programs offered by recreation agencies (Illinois Secretary of State, n.d.). |

| Sports Betting Revenue | |

| Massachusetts | Massachusetts directs 1% of its sports betting revenue to the Youth Development Achievement Fund. This fund, created in 2022, offers financial assistance for higher education programs and OST programs (Bill H.5164, 191st General Court, 2020 [Mass.]). |

| Digital Advertising Tax | |

| Maryland | Maryland instituted a tax on digital advertising revenue in 2020, with potential for funding to support OST programs via the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future (Maryland General Assembly, 2020). |

State-Level Administration of Federal Funds

States exert influence on how federal dollars that flow through the state are spent, with most of the decision-making and oversight in the hands of agencies such as state education and childcare agencies, often working in tandem with governor’s offices and in some cases state legislatures. State agencies generally have a great deal of discretion in administering federally funded programs in their states. While the agencies must follow the requirements of the legislation and take into consideration any nonregulatory guidance from federal agencies, much of the decision-making about how to use the federal funds is up to agency leaders who interpret the legislation and guidance and administer the funds.

The discretion of state agencies is most obvious when it comes to administering the two primary federal funding streams that all states receive a portion of and are administered at the state agency level: 21st CCLC funds and CCDF. The former are typically overseen by state education agencies, while the latter is administered by a range of agencies depending on the state (e.g., agencies pertaining to economic security, education, human and social services, early childhood; Office of Child Care, 2019).

In the case of 21st CCLC funds, state education agencies write the requests for proposals (RFPs), manage the competitions, determine how to measure success, and apply their own interpretation of federal requirements and guidance. State education agencies set priorities for funding, which historically have included age groups to be served, specific types of activities to offer, and geographic regions of the state. They determine grant funding amounts; number of years of funding; minimum hours of operation; and requirements for professional development, measures of success, and more. This translates to tremendous variability in what organizations receive funding, what activities are offered, what the state evaluations include, which communities benefit, and how much staff can be paid. For example, in Vermont, nearly all 21st CCLC funding goes to schools, while in Georgia, the list of grantees is much more diverse. A recent scan of available 21st CCLC RFPs by the Afterschool Alliance (n.d.d) highlights the array of state-level decisions that shape 21st CCLC implementation in each state.

In contrast with 21st CCLC funding using RFPs as the primary vehicle for state flexibility, state CCDF plans are updated every two years, allowing state childcare agencies to shape the implementation in their states. State CCDF plans allow states to demonstrate a commitment to quality care for school-age children and youth by articulating the role of this care in an overall continuum of care, addressing specific licensing requirements for caregivers for school-age children and youth, identifying quality standards and assessment tools, and providing training and technical assistance (Afterschool Alliance, 2022b).

In recent years, there has been some movement to establish new state agencies that bring together early childhood and OST funding streams, such as the Michigan Department of Lifelong Education, Advancement, and Potential (2024), a proposed new Office of Youth Development in Washington, and a new Department of Children Youth and Families as of July 2024 in Minnesota (Minnesota Management and Budget, n.d.).

Coordination and Alignment of Federal and State Funding Streams

Federal and state agencies can make braiding of funds—coordinating funding streams while keeping them separate to support one initiative—easier, by taking a careful look at how their requirements might restrict

which funds can be used for what purposes (Children’s Funding Project, 2023a). One such example is between 21st CCLC funding and the CCDF. Programs that have CCDF funding are expected to charge a copayment to families who are accessing CCDF subsidies. In contrast, 21st CCLC programs are discouraged from charging fees for participation. State agencies administering 21st CCLC and CCDF funds can help programs overcome this hurdle by exploring waivers and other flexibilities in state implementation of these federal funding streams (National Center on Afterschool and Summer Enrichment, 2024). Missouri’s approach illustrates how these discrepancies can be addressed effectively. Starting in the 1990s, a memorandum of understanding between the Missouri CCDF Lead Agency and the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education brought administration of 21st CCLC and school-age CCDF grants under the same office. In 2021, that ongoing memorandum resulted in a new Office of Childhood that includes CCDF and 21st CCLC, along with early childhood programs and services. This allows for greater coordination of resources and grants and ensures that research-based quality practices are implemented across funding streams (Afterschool Alliance, 2024a).

Similarly, the alignment of federal dollars at the state level is illustrative of one way in which state agencies can work together to increase access to programs and reduce barriers to participation by ensuring funds are used in complementary ways and systems are easy to navigate for providers and for families. For example, Georgia, like Utah and other states, has an approach that aligns its CCDF funds with its TANF funds. The Afterschool Care Program, managed by the Georgia Division of Family and Children Services, focuses on ensuring that every child and young person has access to high-quality youth development programming within their community. Roughly $15 million in TANF funding is provided to organizations that offer project-based learning activities and/or apprenticeship experiences during the OST hours (National Center on Afterschool and Summer Enrichment, 2019).

Other states have consolidated the administration of funding streams for OST programs under one agency, office, or division, which then acts as an intermediary. In 2011, California formed the California Department of Education Afterschool Division, which has since evolved to the Expanded Learning Division (California Afterschool Network, 2016, n.d.). This centralized approach is essential to ensure that the administration of the state funding streams and 21st CCLC are well aligned and complementary. With the addition of the newest state funding stream, the Expanded Learning Division of the California Department of Education currently oversees three ongoing funding streams for expanded learning programs, including the After School Education and Safety (ASES) program (originally established by the Proposition 49 ballot initiative), the 21st CCLC program, and the more recently established Expanded Learning Opportunities Program (ELO-P).

However, even with a centralized office administering funds, external partners are often essential for highlighting gaps in services and needs for additional funds and supports. In California, a central access to data for all the major funding streams facilitated the examination of how the three major funding streams in the state are complementing one another and where gaps remain. In particular, state OST leaders have been using data to make the case for more investment in programs for older youth. ASSET’s funding, which is the portion of 21st CCLC funds directed to high school youth in California, totaled $70 million and reached 306 high school OST programs in the 2022–2023 school year, while ASES and the remaining portion of 21st CCLC provided approximately $222 million to 1,125 middle and junior high school programs. In comparison, ELO-P, which reaches only children in grades K–6, is funded at $4 billion annually. Looking at all of California’s OST funding combined, less than 2% supports high school students and less than 5% supports middle school students (Partnership for Children & Youth, n.d.).

In addition to implementing policies that support braiding of funds, state agencies also implement approaches to address the unique needs of communities. For example, given transportation challenges in rural communities, the California Department of Education administers the ASES Frontier Transportation Grant, which is intended to provide supplemental funding for ASES grantees that have transportation needs due to their program site being located in Frontier Areas. Funding began in the 2017–2018 school year, and all programs with this classification are eligible for funding of up to $15,000 per site (California Department of Education, n.d.a,b).

Local Funding and Support for OST

Similar to state policymakers and agencies, local leaders—including mayors, city council members, and county leaders—are critical partners in supporting OST programs. They drive investments, facilitate partnerships, and advocate for OST initiatives, and they can play an important role in increasing access to OST programs in their communities. Local leaders can leverage influence and position to bring together stakeholders from various sectors to collaborate on developing and implementing effective OST initiatives. This can involve organizing meetings, task forces, and networking opportunities to exchange ideas, share best practices, and coordinate efforts (Afterschool Alliance, n.d.b). For example, mayors can

- Lead or contribute to a landscape analysis and identify high-needs communities and “service deserts”;

- Convene a broad set of potential partners, such as community-based organizations, school districts, and city departments;

- Act as a funding entity;

- Provide access to community spaces, including recreation centers and libraries;

- Facilitate data-sharing agreements between cities, community-based organizations, and school districts;

- Assist with transportation needs for expanded access to OST programs;

- Increase public awareness and sustain public attention through initiating media coverage, facilitating awards programs for OST program youth and/or staff, issuing proclamations, and visiting programs; and

- Align programs with key public priorities (Stockman, 2024, p. 1).

Through a grant from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation and the Wallace Foundation (2011), the National League of Cities (NLC) Institute for Youth, Education, and Families selected nine states to host “mayoral summits” to focus on OST programs in 2011. In 2022, more than 40 mayors from the National League of Cities gathered to discuss how to use their office to support learning both during and after school (Pitts & Bartlett, 2022). In 2009, the U.S. Conference of Mayors also included OST as a priority for its action guide for success.

Cities and counties often facilitate OST programs through their established parks and recreation and/or library departments, a preferred mode of service delivery for smaller-sized municipalities with limited resources (see Box 8-3 for discussion of governing structures for local OST programs). Many cities and counties are expanding and enhancing their more traditional forms of OST programs, building on conventional sports-centric models to include more holistic programming frameworks. Collaborations with intermediaries such as Statewide Afterschool Networks have further enriched these endeavors, facilitating the establishment of program quality standards, robust monitoring mechanisms, professional development initiatives, and access to increased funding opportunities. (Discussion on how cities and counties are developing and implementing quality standards can be found in Chapter 6; discussion on addressing barriers to participation can be found in Chapter 4.)

According to the NLC, cities have invested over $3 billion in OST programs and related infrastructure (Afterschool Alliance & National League of Cities, n.d.; Stockman, 2024). Mayoral support for funding OST programs is apparent in cities such as Washington, DC, and Chicago, Illinois. Washington, DC, made a $22 million investment in OST organizations in August 2023 through the Office of OST Grants for Youth Outcomes. In Chicago, the 2023 mayor’s proposed budget included $76 million for youth jobs and programs (City of Chicago, 2023).

Many cities also play the role of direct-service provider through a comprehensive OST-specific department. For example, the City of Roanoke,

Virginia, facilitates OST programs through its Parks and Recreation Department and local libraries. The city leveraged $400,000 of its ARP State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds to expand existing OST initiatives, specifically targeting underserved communities. Through community-based partnerships, the city provides mental health support, tutoring, and mentoring services for young people enrolled in OST programs. The remainder of the program cost has been funded by city general funds (Stockman, 2024).

In rural communities, many OST programs build off existing structures, including county-level parks and recreation programs, school district–level

BOX 8-3

Governance Models for Local OST Intermediaries

Three governance models are commonly used for out-of-school-time (OST) systems, settings, and programs at the local level, according to a 2018 report titled Governance of City Afterschool Systems: A Review and Analysis, which reviewed governing structures for OST programs across 15 U.S. cities (Deich et al., 2018).

Public Agency Model

Under the public agency model, the managerial, fiscal, or administrative support for OST programs is housed in one public entity or through a partnership between two or more public entities. The leader for an OST system under this model can be a mayor, superintendent, or a city agency. Examples include the following:

- In New York City, the OST program is housed in the Department of Youth and Community Development, which, in turn, works with a nonprofit organization to serve young people in more than 800 schools.

- In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a department of recreation was established in 1911 by the Wisconsin Legislature to assign the responsibility of recreation activities for children and youth to school districts. The department of recreation has since undergone several name changes but remains focused on using OST programs to improve the health, educational, and social well-being of Milwaukee children and youth.

- In Oakland, California, the Office of Afterschool Programs is housed in the Oakland Unified School District and coordinates with several nonprofit organizations to support students and families.

- In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Office of Children and Families operates several education programs that include preK, summer employment for teens, and the preK–12 OST office.

Advantages of the public agency model include access to key local policymakers, buy-in from local stakeholders, and the ability to partner with private groups interested in improving economic or social well-being of the city.

or county office of education initiatives, and 4-H programs. Much less is known about the role of local leaders in rural communities. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, smaller tax bases limit the ability of local governments to fund OST programs, and the lack of a community partners and funders makes it even more difficult for rural OST programs to diversify their funding (Fischer, 2019). However, as discussed in Chapter 5, there is significant need for more OST programming in rural communities, and rural communities face unique challenges. More research is needed on rural OST systems, settings, and programs.

Challenges include constraints on how much advocacy an elected or public official can use to drive the initiative, turnover of elected officials and agency staff, and laws that prohibit private funding for government work (Deich et al., 2018, p. 15).

Nonprofit Organizations

Nonprofit organizations, the second model, are funded by private and public sources and can be either single purpose or multiservice. The Family League of Baltimore (Maryland) is one example. As a 501(c)(3), the Family League is a quasi-governmental agency with its own board of directors, half of them appointed by a mayor; it uses its authority to support city- and community-based OST programs. In Omaha, Nebraska, the Collective for Youth works with more than 60 OST providers that reach 7,000 elementary- and middle school-aged youth in 42 Omaha Public Schools. They focus on advocacy, offering resources, and providing quality training for OST providers (Collective for Youth Development, n.d.). Advantages of the nonprofit organization model include more stable leadership than in the public agency model, more flexibility to advocate for policy, and the ability to raise funds from private donors. Challenges include competing with existing nonprofits, lack of direct access to local officials, and uncertainty around funding (Deich et al., 2018).

Networked Home

A networked home, the third model, relies on several organizations for managerial and resource support for OST programs. In 2023, Indianapolis, Indiana, launched an initiative to provide afterschool programs for children in grades preK–5. Partners in this work include the Indianapolis Public Schools, the YMCA of Greater Indianapolis, and community stakeholders. Advantages of this model include strong links to grassroots organizations and a diversified leadership model. Its challenges include the need to involve multiple stakeholders in decision-making (Deich et al., 2018).

SOURCE: Generated by the committee, with data from Deich et al., 2018.

THE ROLE OF INTERMEDIARIES IN SUPPORTING FUNDING AND POLICY

At both the state and local levels, intermediaries can play key roles in helping communities maximize the funding available for OST programs, including working with public agencies to develop requests for proposals, distributing funds to local OST providers, building capacity of local OST providers to access funds, and offering technical assistance and professional development to OST providers to help them ensure quality programming while meeting grant requirements. For example, a number of statewide OST networks were instrumental in helping their state education agencies distribute the ARP state set-asides for afterschool and summer programming (see Appendix B for more detail). At the local level, intermediaries such as Prime Time Palm Beach County (n.d.) distribute funds to local programs to implement innovative programming; develop and help programs utilize quality improvement systems; offer professional development and training, including scholarships for staff who participate; and conduct research to document the impact of programs.

PHILANTHROPIC FUNDING AND SUPPORT

Philanthropy plays a critical role in the youth development field. Foundations—national, regional, community, and corporate (defined in Chapter 3)—have invested in child and youth development, school–community partnerships, and field building. In the past two decades alone, funders supporting OST programs have granted funds to direct-service and intermediary organizations, universities and research institutions, and advocacy and coalition-building entities, and have partnered with businesses and government agencies at all levels on various initiatives. Philanthropic investments have helped develop program evaluations, quality tools, theoretical frameworks, national surveys, data dashboards, and rigorous research that advance and inform the field (Traphagen & Goldberg, 2024).

Philanthropy serves three primary roles: promoting innovation in programming, partnering on public efforts, and advancing the field through investments in research and practice. This section shares examples of roles philanthropy plays in advancing the field; it also highlights ways the philanthropic sector is evolving to deepen its support for children and youth from marginalized and minoritized backgrounds.

Investing in Innovation

Philanthropies’ seed and catalytic dollars play an essential role in launching new areas of inquiry, innovations, and pilot projects, and they

draw attention to areas of OST programming that may be underresourced. For example, the Noyce Foundation, operating from 1990 to 2015, invested in what it called “informal science,” supporting STEM OST programs in the No Child Left Behind era. This investment promoted the growth and evidence base of learning labs, maker spaces, and coding camps, and helped provide college preparation for middle and high school youth from low-income backgrounds (National Center for Family Philanthropy, 2016). The Noyce Foundation invested in tools, evaluations, and professional development for youth-serving practitioners and became a catalyst in the STEM Next Opportunity Fund, designed to encourage a learning exchange of funders for continued STEM investments in OST programs. After its closure, its legacy initiative, STEM Next Opportunity Fund, became a standalone organization and now helps advance the growth and sustainability of the OST STEM field.

Investing in Public–Private Partnerships

Public–private partnerships are critical for supporting the youth development field, especially for providing larger, transformational funding opportunities. Leveraging opportunities and resources of both sectors, public–private partnerships can both accelerate and sustain movements and fields. The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, for example, has invested in a “big bet” strategy for a century, starting with community schools investments in the 1920s, expanding to community education in the 1950s, and including OST programming for much of the 20th century and onward (Young & Quinn, 1963). In the 1990s, the Mott Foundation partnered with ED in support of the 21st CCLC program (Phillips, 2010). The Mott Foundation (2014) also hosted bidder conferences to raise visibility of the opportunity to promote high-quality program design and implementation. And it invested in technical assistance for new federal grantees, leading to the development of the 50 State Afterschool Network, supporting intermediaries and research institutions that continue to grow the shared knowledge base.

Investing in Field Advancement

The third primary role is funding intended for field advancement—creating projects and products in the youth development field to inform policy, research, and practice. For example, the Wallace Foundation has made significant investments in developing research and tools. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Wallace-Reader’s Digest Fund invested in innovative afterschool, community school, and summer programming. Since then, the Wallace Foundation has continued its commitment to the

youth development field—partnering with RAND, a national research institution, to conduct longitudinal studies on the effects of summer programs, the National Summer Learning Project. The first report from this effort, Making Summer Count, offered evidence-based recommendations on how school districts can support voluntary, mandatory, and reading-at-home summer programs (McCombs et al., 2011). The second study, Ready for Fall?, offered initial results in five school districts including 5,600 elementary school–aged students, finding positive improvements in mathematics and offering insights into factors that lead to program improvement in reading and mathematics (McCombs et al., 2014). Six subsequent reports further investigated quality summer learning, examining instructional practices, program quality components, capacity-building, network coordination, and city-level system change (see Wallace Foundation, n.d.).

Future Directions in Philanthropy for OST Programs