The Future of Youth Development: Building Systems and Strengthening Programs (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

Youth development, sometimes known as positive youth development, is “an intentional, prosocial approach that engages youth within their communities, schools, organizations, peer groups, and families in a manner that is productive and constructive; recognizes, utilizes, and enhances young people’s strengths; and promotes positive outcomes for young people by providing opportunities, fostering positive relationships, and furnishing the support needed to build on their leadership strengths”1 (Interagency Working Group on Youth Programs, n.d., para 1). This approach, which evolved from the field of prevention, recognizes individuals as agents in their development. As a field, it encompasses the diverse programs and settings where young people spend their time outside of school and the actors (i.e., implementors, funders, researchers) and systems that support them. Out-of-school-time (OST) programs are a part of the broader field of youth development. The terms OST and youth development programs are sometimes used interchangeably; however, OST speaks to the time programs can happen and youth development speaks to the approach.

In 2002, the National Research Council (National Research Council & Institute of Medicine, 2002) released its report Community Programs to Promote Youth Development. This report was foundational for the field of youth development and continues to be an important resource for individuals working with, studying, or advocating on behalf of youth.

___________________

1 The (positive) youth development approach is commonly applied in multiple settings, including in the home; in residential facilities; in libraries, parks, and camps; and often in out-of-school-time programs.

Commonly referred to today as the “Blue Book” by those in the field, that report reviewed the evidence available at the time on positive youth development, identifying the personal and social assets young people need to succeed, the settings that foster these assets, and ultimately the value of community programs as an opportunity for youth to experience positive developmental settings.

Since the publication of the Blue Book, much of the policy and funding advances related to youth development have come in the form of OST opportunities. OST programs provide promise for learning and development during the critical time when children and youth are not in school. Rich OST experiences give children and youth opportunities for play, discovery, joy, and carefreeness. Participants can try new activities, talk with new people, discover their passions, and develop the supportive relationships they need to thrive. High-quality OST programs offer opportunities to develop skills and capabilities during childhood and adolescence that can help them prepare for adulthood. These skills—such as cultivating strong personal relationships, acting with autonomy, and deriving pleasure from art or sports—can increase their societal contributions and enable them to live fuller lives. Moreover, OST opportunities offer structured safe spaces for children and youth after the school day that allow parents and caregivers to work. Research shows parents overwhelmingly view OST programs as helping working families keep their jobs or work more hours (Afterschool Alliance, 2022), a view that may be more prominent among low-income families, where parents are more likely to be in service occupations with less flexible schedules (Douglas-Hall & Chau, 2007; Harknett et al., 2020). There is also a general consensus that OST opportunities for adolescents are preferable to other less productive or unsafe and unstructured activities teens have access to and that OST remains a critical, ongoing connector to school participation.

Today’s youth development field in the United States is increasingly varied in its settings and programming, and in the children and youth served, which is both a strength and a factor that can make it difficult to describe and study. OST programs may be based in schools or offered through community-based organizations, and in many other settings. Programs can include a range of activities or have a specific focus, such as arts, sports, activism, or academics. Some programs are designed to serve specific populations, such as LGBTQ+, refugee children and youth, or Latine children and youth; others are funded to serve children and youth from households with low incomes. The variation in program foci and design is relevant to understanding the landscape of activities and funding issues and identifying relevant outcomes.

In the decades since the Blue Book, interest and funding for programming to support children and youth in organized activities outside of school

has continued to grow. Developments in the field that followed and may have been inspired by the publication of the Blue Book include codified program practices, systemic support of program quality, recognition of the youth development workforce as a valued asset, and the trajectory of youth outcomes from purely academic to social and emotional competencies. Along the way, the youth development field has maintained roots in strengths-based and community-driven approaches that mitigate persistent gaps in opportunities and outcomes. Nonetheless, much work remains to ensure access to high-quality programs for all children and youth who may benefit. The committee aims to unpack these issues and more, based in the robust evidence now available. It will share conclusions and propose recommendations to fuel directionality in the youth development field in the same spirit of the committee that authored the Blue Book over 20 years ago.

THE STUDY CHARGE AND THE COMMITTEE’S APPROACH

With the support of the Wallace Foundation, the Board on Children, Youth, and Families convened an ad hoc committee to review the evidence on OST activities across geographic settings for children and youth from low-income households.

Specifically, the committee was asked to review the evidence across four key areas: (1) characterizing the array of OST activities; (2) evaluating the strength and limitations of the evidence on the effectiveness of OST activities in promoting learning, development, and well-being; (3) outlining improvements to existing policies and regulations to increase program access and quality; and (4) laying out a research agenda that would strengthen the OST evidence base. In addressing these priorities, the committee was directed to the intersections between economic stress and other factors—such as gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, age, disability, immigrant status, and involvement with justice or child welfare systems—that have operated historically to marginalize young people.

The full statement of task for the committee appears in Box 1-1. The committee also had an opportunity to hear directly from the sponsor at its first public meeting and ask clarifying questions around the statement of task. In this conversation, the sponsor emphasized a few key points: identifying robust qualitative and quantitative studies to review entails thinking about quality standards for inclusion and making clear the strengths and limitations of the research. The sponsor emphasized the need to go beyond discussions of program access to discussions of program quality and to understand where investments and policy changes at all levels—federal, state, and local—can help ensure higher-quality programming for children and youth.

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) will convene an ad hoc committee of experts to conduct a consensus study on learning and development of low-income youth in out-of-school-time (OST) settings across the K–12 age span. Specifically, the study will focus on students from low-income households, across urban, suburban, and rural settings. Analyses of findings will attend to issues of intersectionality of economic stress with other factors that have operated historically to marginalize young people, such as gender, sexual orientation, race, age, disability, and involvement with justice or child welfare systems, among others. The committee will establish and describe quality standards of inclusion to ensure that only the most robust qualitative and quantitative studies are included in the review and will address and make recommendations for the following questions:

- How can OST programs specifically designed to serve K–12 youth from low-income households be characterized (e.g., program goals, audiences, governance structures/staffing, size, dosage, programmatic approaches, and theories of change)? How and why do these characteristics vary among OST programs? Are there any patterns among these organizational dimensions related to community served, focus/purpose, geographic region, or other factors?

- What is the evidence on the effectiveness and outcomes of OST programs for promoting learning, development (social, emotional, intellectual, and physical), and well-being for children and youth from low-income households? How are these constructs defined and measured by programs and in the research literature? Do findings vary by subgroups of low-income youth experiencing additional forms of structural inequality?

- What approaches are linked to positive effects, across a range of quantifiable outcomes? How do results vary by demographic factors (e.g., age, ethnicity/race, gender, gender identity, disability) and program approach (including governance structures and dosage) as well as intersectionality with additional forms of structural inequality?

- What other types of outcomes have been documented in the research (e.g., social, emotional, academic, workforce) and how do these differ by demographic factors (e.g., age, ethnicity/race, gender, gender identity, disability) and program approach (including governance structures and dosage), as well as intersectionality with additional forms of structural inequality?

- How can existing policies and regulations for OST programs be improved to ensure high-quality opportunities for children and youth from low-income households? How might these vary when low-income youth experience additional forms of structural inequality?

- What are the existing gaps in the literature that can be addressed to produce more robust findings about how OST can support learning and development for children and youth from low-income households? How might these vary when low-income youth experience additional forms of structural inequality?

Defining the Study Scope

In order to carry out its charge, the committee had to first define its scope of interest. To narrow the scope, the committee relied on the established definition of organized activities, which are characterized by structure and adult supervision, have scheduled meeting times, and emphasize skill-building. They typically denote for whom (school-age, child, adolescent, youth), what (activities, programs, organizations), where (school based, community based), and when (after school, extracurricular, summer, non-school, out of school) youth development programs will occur (Mahoney et al., 2005).

The committee further narrowed its review to focus on the following:

- Organized activities in OST settings, defined as structured school- and community-based programs offered outside of school hours that occur with regular frequency. This could include programs that are distinct from the school curriculum and are offered before or after school, on weekends, or during the summer. This report looks primarily at programs after school during the afternoon and early evening and on weekends.2

- Programs serving children and youth in grades K–12 (between the ages of 5 and 18) from households with low incomes, where possible. The committee recognizes that young people who are contending with economic insecurity may also face other intersecting challenges or characteristics.

- Programs serving children and youth from low-income households, across urban, suburban, and rural settings with attention to issues of intersectionality of economic stress with other factors as defined in its statement of task. In some cases, the literature the committee reviewed did not present details or disaggregate by the aforementioned factors. In those cases, the committee described the population focus, or lack thereof, in its description of the evidence.

___________________

2 While summer programming provides important developmental opportunities for children and youth, the committee did not focus specifically on this body of work, as a recent National Academies report, Shaping Summertime Experiences: Opportunities to Promote Healthy Development and Well-Being for Children and Youth (2019c), examines the impact of summertime experiences on the developmental trajectories of school-age children and youth. It discusses impacts across four areas of well-being, including academic learning, social and emotional development, physical and mental health, and health-promoting and safety behaviors. It also reviews the state of the science and available literature regarding the impact of summertime experiences.

The Committee’s Approach

A variety of activities and sources informed the committee’s work. Foremost, the study benefited from the varied perspectives of its 15-member committee, which collectively holds expertise in public policy, child and adolescent development, developmental psychology, sociology, population health, juvenile justice, economics, and evaluation, program design and delivery, and the populations that are the focus of this study. Many members also had previous experience providing direct services to children and youth through OST programs. (See Appendix D for biographical sketches of the committee.) The committee met in formal closed sessions five times over the course of its study and conducted additional deliberations in several ad hoc virtual meetings.

Sources of Evidence

The committee gathered and synthesized the available evidence pertaining to the questions raised in its statement of task. It reviewed scientific literature, gray literature (i.e., literature produced by organizations outside of the traditional or academic publishing sphere), papers and reports produced by youth-focused organizations, and previous reports from the National Academies (see Box 1-2). To augment its activities, the committee commissioned two systematic literature reviews. Mathematica conducted a review of peer-reviewed studies based on quantitative data. To complement this work, Youth-Nex, a research center at the University of Virginia, reviewed studies based on mixed-methods and qualitative data.3

The committee held three public information-gathering sessions (National Academies, 2024a). In the first session, representatives of national, state-, and city-level organizations shared their perspectives on investments and partnerships that would support OST program access, quality, and assessment, as well as professional pathways for the OST workforce. In the second and third public sessions, young people and staff from program settings across the country shared their personal experiences participating in and supporting community programs. Program participants discussed the opportunities they see in these programs, what matters most to them about these programs, and how they define a successful program, among other areas. Program staff shared ways in which their organizations are reaching and serving young people, and they illuminated OST workforce challenges through their personal experiences.

The committee also requested memos and commissioned papers from experts in academia and organizations that serve children and youth.

___________________

3 These reviews are available in the committee’s public access file; access can be requested via https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/managerequest.aspx?key=DBASSE-BCYF-22-03

BOX 1-2

Relevant National Academies Reports

This report is a contribution to a series of reports by the National Academies that focus on opportunities and gaps in positive developmental experiences, elevating the strengths of children, youth, and their families. Together, these reports offer a comprehensive exploration and set of recommendations for the potential and promise of coordinated programs, systems, and investments to support better outcomes for children, youth, families, and communities.

- Reducing Intergenerational Poverty (National Academies, 2024b)

- Closing the Opportunity Gap for Young Children (National Academies, 2023)

- A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty (National Academies, 2019a)

- Shaping Summertime Experiences: Opportunities to Promote Healthy Development and Well-Being for Children and Youth (National Academies, 2019c)

- The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth (National Academies, 2019d)

- Identifying and Supporting Productive STEM Programs in Out-of-School Settings (National Academies, 2015)

- Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Development in Children and Youth: A National Agenda (National Academies, 2019b)

- Community Programs to Promote Youth Development (National Research Council & Institute of Medicine, 2002)

- From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development (Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2000)

The topics included a review of the work of the Grantmakers for Education Out-of-School Time Impact Group, city-level supports and governance structures of OST activities, findings from an ongoing study estimating OST program costs (American Institutes for Research [AIR], 2024), and the experiences of youth workers in the United States (AIR, 2025). The committee also commissioned the Afterschool Alliance to provide additional data on OST participation and demand among low-income families on a national level.

Standards of Evidence on Program Effectiveness and Outcomes

The youth development field is rich and diverse. The field is upheld by a set of principles including strengths-based and context-driven approaches that inherently promote multiplicity in program offerings. The field is organized by OST systems that vary in their governance and goals

and work in a multitude of settings: schools, communities, parks, places of worship, and more. The workforce comes with preparation, credentials, and experience in multiple fields and is ideally rooted in the local community. Programs are complex; they have many moving parts and are emergent—in other words, outcomes may manifest differently for different youth (even for youth who attend the same activity). Activities constantly evolve, and two programs based on the same principles may shift in different ways in reflection of the assets, context, and talents of the implementers and participants. For example, two local affiliates of the same national organization (e.g., Boys & Girls Clubs, Girls Inc.) can vary in program quality, norms, youth–staff interactions, and specific activities, even when they are founded on the same principles, programming, and staff training (Seitz et al., 2021; Simpkins, 2015). This variety is more expansive when considering the various programs and activities offered, such as the range of academic clubs across multiple high schools. Scholars have argued that regarding all possible activities in the youth development field as a singular intervention is not tenable, as activities vary in structure, quality, and youth experiences (Mahoney & Zigler, 2006). Still, this array of activities and approaches is a strength, creating greater opportunity for youth and families.

When studying such complex systems, it is vital to draw on multiple sources of evidence based on rigorous quantitative and qualitative methodologies to help inform research, practice, and policy decisions. As described above, the members of the study committee have a range of disciplines, perspectives, and methodological approaches to developing and interpreting robust evidence. It therefore relied on a range of approaches to capture the evidence on the effectiveness and outcomes of OST programs, as detailed in Chapter 7.

Every method has strengths and challenges, and varied sources of evidence provide complementary information on OST programs. Rich qualitative narratives, for example, provide insight into the complex, multidetermined processes that are challenging to discern in many generalizable quantitative methods. Consolidating evidence across multiple methodologies helps provide a more comprehensive understanding of how activity participation matters, for whom, and under what conditions.

Throughout this report, the committee summarized the evidence from robust quantitative and qualitative evidence. In some cases, we drew on available causal evidence to understand the direct relationship between program participation and youth outcomes and on other evidence to illuminate relationships, future research directions, and considerations for policy and practice. Additionally, the committee highlights throughout the report relevant studies and examples, wherever available, across demographic and geographic considerations, such as research, practice, and/-

or policy on rural and Indigenous communities, youth involved in other systems of care (e.g., justice, child welfare), and youth with disabilities. Because of the limited availability of such evidence, the committee’s recommendations invite further investments in research that deepen understanding of context and variation in outcomes across subgroups and at demographic intersections.

Language and Terminology

Language in the field is as varied as the settings in which it is offered. Language matters because it is the way that children, youth, families, staff, partners, and community members identify with what they engage in. Today, prominent terms describing youth programs include youth development, afterschool, and out-of-school-time programs. The latter two reflect the program or activity in its relationship to school, as opposed to its own value or purpose. The committee observes that people who benefit from youth development programs do not use these terms widely, nor do they identify with names used by common funding streams, creating a disjuncture between the system-level architecture of the field (what system leaders use to refer to programs), the workforce (those who run and work in the field), and those for whom it is intended (children, youth, and families). As much as use of a common set of terms may further unite the fields that support youth development, the committee recognizes the value of locally driven and relevant program language, as well as the complexities created by the push and pull of funding mechanisms in naming programs.

Throughout the report, the committee used people-first language, using the terms and definitions laid out in Box 1-3 where applicable. At the start of each chapter, the committee also captures chapter-specific key terms and entities to improve understanding of the report for all audiences.

BACKGROUND ON THE HISTORY AND EVOLUTION OF YOUTH DEVELOPMENT AND OST PROGRAMS

Throughout the study process the committee discussed the history of youth development and OST programming as critical to understanding the state and direction of programs today, including policy and funding issues, program practices, program access and availability, and research. This history is particularly important in understanding contemporary developments that have contributed to moving the field of youth development forward and the focus and accessibility of programs that serve children and youth, especially those subpopulations that are the focus of this study. The following sections briefly review these origins and recent advancements.

BOX 1-3

Key Terms Used in the Report

- Agency: A public office (e.g., a state or local education agency, governor’s or mayor’s office) that may serve as the funder for organizations and programs and/or a backbone support for a system; in some cases, the term refers to a program implementer.

- Children: Individuals ages 5–12.

- Direct service: Staff who work directly with participants in out-of-school-time (OST) programs.

- Extracurricular (activities/clubs/sports): School-sponsored activities, common in middle and high school levels.

- Intermediary: An organization or agency that oversees the OST system policies and strategies, and coordinates resources, money, and expertise; can serve at the county, city, state, or regional levels.

- Intersectionality: As defined by Crenshaw (1989), a framework that recognizes the intractable overlap of social positions (e.g., race, gender) that cannot be otherwise understood separately, and furthermore that intersecting systems of power inform people’s social positioning and experiences. Crenshaw’s (1989) conceptualizations of intersectionality highlight the role of race, ethnicity, gender, orientation and identities as objects of overlapping areas of marginalization, discrimination, and structural inequality.

- Low income: The committee recognizes that the U.S. Census Bureau sets specific thresholds to define poverty for households. However, the eligibility requirements for children and youth to participate in OST activities and programs that primarily serve youth from low-income households are often defined as households that qualify for free and reduced-price school meals, which is reflected in the data and research around OST activities and programs. Therefore, the committee follows the general practice of using the term low income to encompass individuals, households, and families with incomes who are eligible for free and reduced-price school meals.

- Marginalized: In a scoping review of 50 years of research, Fluit et al. (2024) synthesized an integrated definition of marginalization as “a multifaceted concept referring to a context-dependent social process of ‘othering,’ where certain individuals or groups are systematically excluded based on societal norms and values, as well as the resulting experiences of disadvantage” (p. 1). The authors note that both the process and outcomes of marginalization can vary significantly across contexts (Fluit et al., 2024).

- OST programs and activities: Structured school- and community-based programs and activities offered outside of school hours, that are not part of the school curriculum, and that occur with regular frequency. These include programs and activities offered before school, after school, on weekends, or during the summer. The terms programs and activities are sometimes used interchangeably in this report.

- OST systems and settings: The field-level infrastructure and locales (i.e., places) that support program implementation.

- Youth development or positive youth development: The underlying philosophy of programs (i.e., strengths based, context driven); the term can describe actors (i.e., implementers, funders, researchers), settings, and program types. The youth development field includes the approach, actors (i.e., implementors, funders, researchers), settings, and program types.

- Youth development practitioner: One who works directly with children and youth in a part- or full-time capacity in an OST program.

- Youth or adolescent(s): Individuals ages 13–18.

Throughout the report, when discussing subpopulations disaggregated by race, the committee generally used the terms White, Black, Latine, Asian, and Native American. However, the term Hispanic is used, primarily in Chapter 4, when reporting results of national surveys that employed this term.

__________________

NOTE: Other terms that refer to programs are commonly used in the field but are not used widely in this report: organized activities, informal learning, and expanded learning.

It is helpful to first note that historical and contemporary developments around OST programs have been shaped by four underlying drivers:

- Safety and Supervision: OST settings were first positioned as safe spaces between home and school, whereby children and youth could be supervised by trusted adults in structured spaces as their families worked (Halpern, 2003; Noam & Rosenbaum Tillinger, 2004). The role of OST as a support structure to working families grew in prominence with the labor market shifts of the 1970s and onward (Halpern, 2003; Malone, 2013). This positioning was also used to emphasize the need to prevent risky behaviors and juvenile crime (Fight Crime, Invest in Kids, 1998; FrameWorks Institute, 2001). Although some scholars have highlighted that an emphasis on crime and safety stands to label both certain communities and young people as unsafe, the risk prevention—especially for older youth—remains a consideration in public support of OST programs, especially with focus on older youth (FrameWorks Institute, 2001; Malone, 2013; see also Pittman & Cahill, 1992).

- Academic Learning: The second driver that has shaped policy discourse is the role program participation plays in supporting academic learning. Debates on whether such programs need to extend the school day to boost academic achievement have led to tighter coupling of some OST programming with academic

- outcomes under certain public funding streams (e.g., 21st Century Community Learning Centers), and have created an opportunity for the growth of programs offering targeted interventions, homework assistance, or tutoring (Halpern, 2003; see examples in Borman & D’Agostino, 1996; Lauer et al., 2006). The central debate surrounding this driver is whether this positioning narrows the purposes of the field or bolsters connections to learning spaces in advancing student success (Malone, 2013).

- Preparing the Future Workforce: The third driver focuses on workforce and skills development, particularly pertaining to adolescent youth (Malone, 2013). Through both federal levers and public–private partnerships, there is increased attention to the role of youth–adult relationships through mentoring, career counseling, and exploratory opportunities for career readiness (e.g., internships, preapprenticeships, job shadowing, service learning; see overview of each pathway in Clagett, 2015; Midwest Regional Educational Laboratory Program, 2018; Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education, 2015; Ross et al., 2020). Federal investments such as the Job Corps, YouthBuild, and programs for youth through the Departments of Labor and Justice have forged new funding opportunities for the field to support workforce development (see Chapter 8 for overview of each investment area).

- Whole-Child Development: The youth development field’s embrace of whole-child development4 is clear (Cantor & Osher, 2021; Cantor et al., 2019, 2021; National Research Council & Institute of Medicine, 2002; Osher et al., 2020; Search Institute, 2007). Especially after the No Child Left Behind era, when practitioners experienced fatigue for being held accountable to academic tests, youth development practitioners began to embrace a more holistic approach to whole-child development. See, for example, the framework of Nagaoka et al. (2015) and codifying practices to explicitly support learning and development. Other popular models that elevate whole-child learning and development are the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Whole School, Whole Community, and Whole Child framework (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024) and the Science of Learning and Development, which elevate the strengths and assets of individuals as agents in their own learning and development, while prioritizing alignment across settings and systems (Darling-Hammond et al., 2020). In addition to explicit skills development, whole-child

___________________

4 Tenets of whole-child development such as problem-solving and relationships often resonate with families. At times, the term whole-child development has been conflated with mental health and social and emotional learning.

- models recognize the interconnected nature of multiple actors in a young person’s life, contributing to the rise of theories and value for systemic approaches, as discussed in Chapters 2 and 3. Public funding supports whole-child efforts, such as community schools and Promise Neighborhoods (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.).

Early Years

The history of the youth development field in the United States goes back well over a hundred years. Most historians describe the emergence of OST programs and activities in the late 1800s as resulting from several large historical patterns—the rise of compulsory schooling, combined with decreased child labor, increased urbanization, increased parental (including maternal) employment, and a rise in single-parent households. This led to a gap between the end of the school day (usually around 2:30 or 3:00 p.m.) and the time when parents got home from work. This was particularly pronounced in urban areas, which grew steadily during the 1800s and 1900s (Halpern, 2003; Mahoney et al., 2009).

The earliest organizations providing afterschool programming emerged in the mid-1800s: the YMCA, or the Y, was founded in 1844 (Mjagkij & Spratt, 1997), and the first Boys Club, which eventually became Boys & Girls Clubs of America,5 was founded in 1860. Settlement houses6 were also precursors to today’s youth development field, with some settlement organizations offering activities and access to facilities, such as gymnasiums and playgrounds, for Black individuals and European immigrants, particularly in urban areas (Theriault, 2018). Many other large youth organizations and national investments were formed in the early 1900s, including 4-H (1902), Scouts (1910), and Camp Fire Girls (1910), with the goal of providing spaces that fostered positive youth development. These organizations formed their approaches around supporting adolescents through a period of “storm and stress,”7 which was the predominant theory shaping developmental research at the time (LeMenestrel & Lauxman, 2011).

However, access to programs and program goals differed across groups. These large youth organizations were founded during the Jim Crow era,

___________________

6 In the United States, settlement houses functioned as community centers—offering a wide range of cultural and social services, including education, health care, childcare, and employment resources. They were typically located in impoverished urban areas and served the residents of these neighborhoods (Hansan, 2011; Library of Congress, n.d.).

7 Adolescence has been considered a period of heightened stress because of changes experienced during this time, including physical maturation, drive for independence, increased salience of social and peer interactions, and brain development. This has historically led some researchers to characterize adolescence as a time of “storm and stress” (Casey et al., 2010).

with Plessy v. Ferguson enabling states to legalize segregation in 1896 (Hoffer, 2012). As documented by Theriault (2018), Black young people were often barred from newly created parks, recreation centers, and youth centers through exclusionary “membership systems,” or they were dissuaded from attending these settings through negative microinteractions, discrimination, and violence. Elsewhere, Johnston-Goodstar (2020) and Halpern (2003) describe how Native American youth were largely excluded from these mainstream organizations; when they were allowed to participate, they were met with different goals. These authors report that strength and character through sport were features of programming for White children, but for Native American children and immigrant children programming was associated with desires to protect, control, civilize, and “Americanize” them alongside the progressive education ideas of enrichment and organized play (Halpern, 2003, p. 24; Johnston-Goodstar, 2020).

Theriault (2018) also documents how discrimination and segregation often fueled the creation of Black community-created spaces. In reference to church-based settings for youth, Theriault (2018) notes, “The developmental significance of having spaces free of White supremacy during the era of Jim Crow is impossible to quantify” (p. 9). Several YMCAs were founded by and for Black communities in the late 1800s; many struggled financially and did not survive more than a few years. Nonetheless, iconic and long-lasting organizations exist today (e.g., in Chicago, Illinois, and Washington, DC) in times of shifting community demographics (Mjagkij, 2003). Anthony Bowen, a prominent religious leader and educator, a council member of the District’s Seventh Ward, and the first Black clerk at the U.S. Patent Office, was the founder and president of the world’s first Black YMCA (YMCA, n.d.). Hope et al. (2023) argue that this legacy is central to understanding the ingenuity and persistence in developing spaces for positive development in the sociohistorical context of racism and oppression facing children and youth from marginalized backgrounds (Hope et al., 2023).

20th-Century OST: From Safety to Learning

The first half of the century saw changes that catalyzed further formalization of OST programs to support families facing distress from world wars and the Great Depression. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 reduced the number of child laborers; this, coupled with an increasing number of women working during World War II, meant there were fewer adults to watch over children and youth after the school day. The first U.S. government childcare facilities were established during this time (Green, 2024).

Enrichment, learning, and childcare exemplified the role of OST during the 20th century. Schools were eliminating or decreasing arts, music, health, and recreation programming, so OST programs focused on these activities (Halpern, 2003).

With the 1960s War on Poverty, there was an emerging emphasis on supporting learning and opportunities for children from low-income households (Halpern, 2003). As labor market patterns begin to shift during the 1970s, the childcare function, in addition to enrichment and learning, reemerged as an important element to OST programs. Title XX and Dependent Care Block Grants are examples of the 53 federal childcare initiatives of the 1980s that supported working families and access to OST programs (Besharov & Tramontozzi, 1988; Halpern, 2003; Stephen & Schillmoeller, 1987). Organizations such as the School-Age Child Care Project (today’s National Institute on Out-of-School Time) and School Age Child Care Alliance (today’s National AfterSchool Association) emerged (Malone, 2013; Neugebauer, 1996).

With the publication of the 1983 A Nation at Risk (National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983) and the subsequent standards-based accountability movement within the education sector, there was an increased emphasis on the link between OST and academics (Malone, 2013). A focus on academics often hampered the development of other artistic and creative expressions in OST (Baldridge et al., 2024).

According to Kwon (2013), during this period, moral panic around adolescents, as well as paternalism, shaped the purposes and practices around OST programming, especially for Black and Latine populations. Young people were the focus of social anxieties over urbanization, increasing social inequality, crime, and changing sexual norms (Kwon, 2013). Community-based youth organizations grew quickly in urban centers in the wake of legislation that arose from the War on Drugs. In the 1980s and 1990s youth programs were positioned as spaces that offered an alternative to the crime of the urban settings and allowed for the containment and control of Black and Latine youth—preventing crime among males and policing the sexualities of young girls (Baldridge et al., 2024; Kwon, 2013). OST programs have been viewed as critical in preventing juvenile crime, substance use, and risky sexual behavior.

Contemporary Developments

In the late 1990s, researchers published a report (Catalano et al., 2002) confirming that prevention programs that made assumptions about who should be considered “at risk” and focused on curtailing risky behaviors did not work; instead, programs that focused on youth assets, were relationship based, and were grounded in culture and context did work to support positive youth development (and avoidance of unhealthy risk). The field of youth development aims to counter deficit frames of risk to focus on strengths or assets of individuals and communities.

In many ways, the Catalano et al. (2002) study marked a wider recognition of these attitudes in the evidence and in federal funding in the

United States. The research was followed by a series of studies that looked at structured versus unstructured time in programs, finding that many popular community-based models of harm reduction, such as midnight basketball, could in fact be harmful rather than helpful for participants. Thus, funding for structured programs became more prevalent.

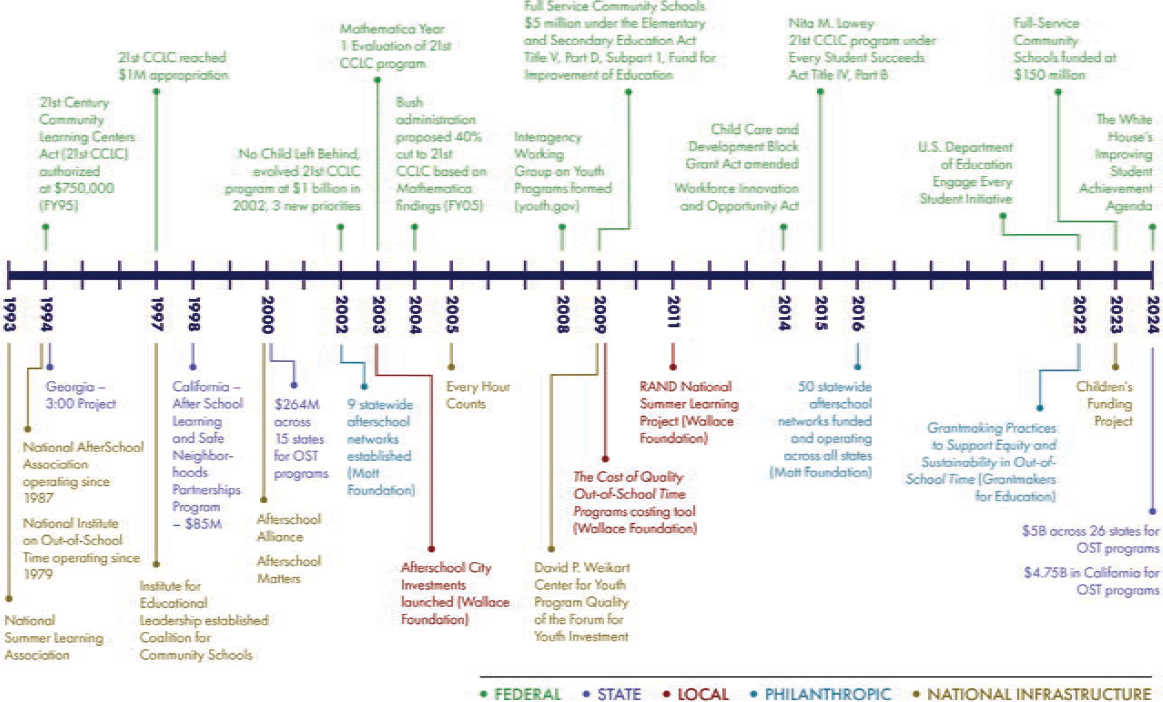

The youth development field has been growing since the 1990s; this growth has accelerated since the 2000s, specifically around (1) the expansion of program quality and practices, (2) growing recognition of the youth development workforce, (3) the rise of coordinating systems, (4) growing scholarship around these already mentioned areas, as well as program effectiveness and outcomes (see Chapter 2 for theories that have informed the field), and (5) dedicated public and philanthropic funding (Figure 1-1 provides a timeline of some of the major events and investments in OST programs and systems since the 1990s). Evidence-based frameworks, statements, and books began to emerge to inform policy and practice at scale, leading to a deeper understanding of the field and its components (see, e.g., C. S. Mott Foundation Committee on After-School Research and Practice, 2005; Economic Policy Institute, 2008; Peterson, 2013; Pittman & Irby, 1996). The numbers of youth-serving organizations, intermediaries, and scholars dedicated to the youth development field have increased. Today’s OST programming is marked by diversity of purpose, organizational type, and resources.

The field was greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Scholars called this a “disturbance in the ecosystem” (Akiva & Robinson, 2022, p. 4). When schools shut down in spring 2020, so did OST programs. While many OST programs reopened quickly to meet the needs of essential workers, many small OST programs, without large financial cushions, closed their doors for good. Among those programs that stayed open, leaders and staff in OST programs were intentional and active during the pandemic shutdown, adapting programing to offer online activities for young people (Fornaro et al., 2021), while others shifted their efforts to food insecurity and getting learning supplies to children (Sliwa et al., 2022). Intermediaries and philanthropic organizations8 supported these efforts to ensure the continuity of services and to fill gaps in services (Every Hour Counts, 2023; Hartmann et al., 2024). Still, providers remain concerned with staffing shortages and program operating costs as pandemic relief funds end

___________________

8 For example, intermediaries and other coordinating entities assisted program providers by increasing online opportunities for staff professional development and providing funding to programs (Every Hour Counts, 2023). In addition, the Grantmakers for Thriving Youth OST Impact Group, comprising 125 foundations’ staff, pooled funding to strengthening cross-sector partnerships, leading to two reports, Building Community from Crisis: A Collaborative Fund for the Out-of-School Time Field (Jung, 2022) and Grantmaking Practices to Support Equity and Sustainability in Out-of-School Time (Grantmakers for Education, 2022). This group plays an important role in elevating OST issues across the funding community and creating space for collective problem solving and is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

(Afterschool Alliance, 2024; See Box 8-1 and Appendix B for more discussion of pandemic relief funds).

Programs continue to serve many functions and sometimes exhibit tension around school goals (i.e., supporting young people to succeed in school) versus enrichment goals (i.e., learning topics not included in school curriculum; Akiva et al., 2023). These multiple functions and purposes have been reproduced in the ways in which programs are governed and funded, with variation across federal, state, local, and philanthropic funding streams. Funding gaps for OST programs today continue to reify a system in which more privileged families can “pay to play” to have access to more quality OST opportunities (see Chapter 8).

With the rise of coordinating entities to support program efforts came the charge of promoting access to programs for all young people through community mapping of programs and participants among other efforts. Initially, efforts to improve access focused on having programs nearby. However, access and transportation are not enough to lead to improved outcomes for children and youth—they need access to high-quality programs. While access remained a challenge, funders quickly turned to supporting quality improvement and outcome measurement efforts, potentially in response to trends in education (e.g., No Child Left Behind) and roadblocks in coordinating data systems to do the mapping. Along the same timeline, public funders started to prioritize structured, high-quality programs, drawing funding away from programs that allowed adult allies or youth development practitioners to reach children and youth where they are.

The field has continued to evolve in its thinking around quality, and efforts are under way that recognize that program quality must incorporate responsiveness to the community, family, and young people—their lives, concerns, and ways of knowing—and designing programs with child, youth, and family assets and needs at the center. These efforts remain nascent, however, and have not permeated the majority of the field. Together, these movements have largely led to programs serving those who elect to attend, but not all children and youth who could benefit. Access to quality programming has become more dire with less access among low-income and marginalized youth (Afterschool Alliance, 2020). This report is intended to point the way forward toward developments that will support broad participation in high-quality programming, so that all children and youth have the opportunity to benefit and thrive.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

In the following chapters, the committee will expand on the contemporary developments around the youth development field and OST programming introduced in this chapter. Chapter 2 reviews developmental and ecological

theories that describe how young people may learn and grow within programs and what may influence them within these settings. This chapter offers frameworks and models for how the youth development field approaches programs and the tools and trainings that are used to support program quality discussed later in the report. Chapter 3 builds on ecological theories to spotlight systems and sectors within the OST ecosystem that shape learning and development in programs, and how programs are developed, delivered, and accessed. Chapter 4 reviews the landscape of OST programs and program characteristics, participation data and trends, and issues affecting enrollment and participation. Chapter 5 offers a picture of the workforce supporting OST experiences. Chapter 6 discusses the implementation of programs, looking at program quality efforts and participant experiences. Chapter 7 reviews the evidence base on effectiveness and outcomes for OST programs. Chapter 8 reviews public and private funding and policies supporting OST systems, settings, and programs. Chapter 9 lays out the path forward for the youth development field, with a list of recommendations for policymakers, funders, and intermediaries to ensure high-quality opportunities for all children and youth.

REFERENCES

Afterschool Alliance. (2020). America After 3PM: Demand grows, opportunity shrinks. https://afterschoolalliance.org/documents/AA3PM-2020/AA3PM-National-Report.pdf

———. (2022). Access to afterschool programs remains a challenge for many families. https://afterschoolalliance.org/documents/Afterschool-COVID-19-Parent-Survey-2022-Brief.pdf

———. (2024). Afterschool WORKS! https://www.afterschoolalliance.org/documents/After-schoolWorks_PolicyAsks%202024FINAL.pdf

Akiva, T., Delale-O’Connor, L., & Pittman, K. J. (2023). The promise of building equitable ecosystems for learning. Urban Education, 58(6), 1271–1297.

Akiva, T., & Robinson, K. H. (Eds.). (2022). It takes an ecosystem: Understanding the people, places, and possibilities of learning and development across settings. Information Age Publishing.

American Institutes for Research (AIR). (2024). Out-of-school time cost study. https://www.air.org/project/out-school-time-cost-study

———. (2025). The power of us: The youth fields workforce. Findings from the National Power of Us Workforce Survey. https://wallacefoundation.org/sites/default/files/2025-05/power-of-us-the-youth-fields-workforce.doi_.10.59656%252FYD-G3634.001_0.pdf

Baldridge, B. J., DiGiacomo, D. K., Kirshner, B., Mejias, S., & Vasudevan, D. S. (2024). Out-of-school time programs in the United States in an era of racial reckoning: Insights on equity from practitioners, scholars, policy influencers, and young people. Educational Researcher, 53(4), 201–212.

Besharov, D. J., & Tramontozzi, P. N. (1988, May 2). Child care subsidies: Mostly for the middle class. The Washington Post.

Borman, G. D., & D’Agostino, J. V. (1996). Title I and student achievement: A meta-analysis of federal evaluation results. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 18(4), 309–326.

Cantor, P., Lerner, R. M., Pittman, K., Chase, P. A., & Gomperts, M. (2021). Whole-child development, learning, and thriving: A dynamic systems approach. Cambridge University Press.

Cantor, P., & Osher, D. (Eds.). (2021). The science of learning and development: Enhancing the lives of all young people. Routledge.

Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L. & Rose, T. (2019). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science, 23(4), 307–337.

Casey, B. J., Jones, R. M., Levita, L., Libby, V., Pattwell, S. S., Ruberry, E. J., Soliman, F., & Somerville, L. H. (2010). The storm and stress of adolescence: Insights from human imaging and mouse genetics. Developmental Psychobiology: The Journal of the International Society for Developmental Psychobiology, 52(3), 225–235.

Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A. M., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2002). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Prevention and Treatment, 5, 1–104.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Whole school, whole community, whole child (WSCC). https://www.cdc.gov/whole-school-community-child/about/index.html#:~:text=WSCC%20is%20CDC’s%20framework%20for,based%20school%20policies%20and%20practices.

Clagett, M. G. (2015). Advancing career and technical education (CTE) in state and local career pathways project: Final report. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Career, Adult, and Technical Education. http://s3.amazonaws.com/PCRN/docs/AdvCTEFinal-Report012816.pdf

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167.

C.S. Mott Foundation Committee on After-School Research and Practice. (2005). Moving towards success: Framework for after-school programs. Collaborative Communications Group. https://www.oregon.gov/ode/schools-and-districts/grants/ESEA/21stCCLC/Documents/movingtowardsuccessframeworkforafterschoolprograms.pdf

Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2020). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140.

Douglas-Hall, A., & Chau, M. (2007). Most low-income parents are employed [Fact sheet]. https://www.nccp.org/publication/most-low-income-parents-are-employed

Economic Policy Institute. (2008). The broader, bolder approach to education.

Every Hour Counts. (2023). Lighting the path forward: How afterschool intermediaries have supported youth and communities during the pandemic and what they’ve learned along the way. https://drive.google.com/file/d/18oAVPNRqqYeWLnLG4MhG5x0PLOOlvZvQ/view

Fight Crime, Invest in Kids. (1998). Quality child care and after-school programs: Powerful weapons against crime. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED417849.pdf

Fluit, S., Cortés-García, L., & von Soest, T. (2024). Social marginalization: A scoping review of 50 years of research. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–9.

Fornaro, C. J., Struloeff, K., Sterin, K., & Flowers, A. M., III. (2021). Uncharted territory: Educational leaders managing out-of-school programs during a global pandemic. International Studies in Educational Administration, 49(1).

Frameworks Institute. (2001). Reframing youth issues for public consideration and support: A frameworks message memo. https://www.frameworksinstitute.org/app/uploads/2020/03/MesMemo_Reframing_Youth.pdf

Grantmakers for Education. (2022). Grantmaking practices to support equity and sustainability in out-of-school time. Ed Funders. https://www.edfunders.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/GrantmakingPracticesOSTRecoveryOpportunityFund10-7-22.pdf

Green, R. A. (2024). Parental engagement: Factors parents and guardians consider when selecting an out of school time (OST) program [Doctoral dissertation]. Holy Family University.

Halpern, R. (2003). The promise of after-school programs for low-income children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(2), 185–214.

Hansan, J. E. (2011). Settlement houses: An introduction. Social Welfare History Project. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/settlement-houses/settlement-houses/

Harknett, K., Schneider, D., & Luhr, S. (2020). Who cares if parents have unpredictable work schedules? The association between just-in-time work schedules and child care arrangements. Social Problems, 69(1), 164–183. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spaa020

Hartmann, T., McClanahan, W., Duffy, M., Cabral, L., Barnes, C., & Christens, B. (2024). Responding, reimagining, realizing: Out-of-school time coordination in a new era. Research for Action.

Hoffer, W. H. (2012). Plessy v. Ferguson: Race and inequality in Jim Crow America. University Press of Kansas.

Hope, E. C., Anyiwo, N., Palmer, G. J., Bañales, J., & Smith, C. D. (2023). Sociopolitical development: A history and overview of a Black liberatory approach to youth development. American Psychologist, 78(4), 484.

Institute of Medicine & National Research Council. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9824

Interagency Working Group on Youth Programs. (n.d.). What is positive youth development? U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://opa.hhs.gov/adolescent-health/positive-youth-development

Johnston-Goodstar, K. (2020). Decolonizing youth development: Re-imagining youthwork for indigenous youth futures. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 16(4), 378–386.

Jung, M. (2022). Building community from crisis: A collaborative fund for the out-of-school time field. Grantmakers for Education. https://www.edfunders.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/CaseStudyBuildingCommunity_09142022.pdf

Kwon, S. (2013). Uncivil youth: Race, activism, and affirmative government mentality. Duke University Press.

Lauer, P. A., Akiba, M., Wilkerson, S. B., Apthorp, H. A., Snow, D., & Martin-Glenn, M. (2006). Out-of-school time programs: A meta-analysis of effects for at-risk students. Review of Educational Research, 76(2), 275–313. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543076002275

LeMenestrel, S. M., & Lauxman, L. A. (2011). Voluntary youth-serving organizations: Responding to the needs of young people and society in the last century. Journal of Youth Development, 6(3), 137–152.

Library of Congress. (n.d.). Settlement houses/hull-house. https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/join-in-voluntary-associations-in-america/about-this-exhibition/a-nation-of-joiners/changing-america/settlement-houses-hull-house/

Mahoney, J., Vandell, D. L., Simpkins, S., & Zarrett, N. (2009). Adolescent out-of-school activities. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (3rd ed., pp. 228–269). John Wiley.

Mahoney, J. L., Larson, R. W., & Eccles, J. S. (Eds.). (2005). Organized activities as contexts of development: Extracurricular activities, after-school and community programs. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Mahoney, J. L., & Zigler, E. F. (2006). Translating science to policy under the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001: Lessons from the national evaluation of the 21st-Century Community Learning Centers. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27(4), 282–294.

Malone, H. (2013). Building a broader learning agenda: The evolution of child and youth programs toward the education sector [Doctoral thesis]. Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Midwest Regional Educational Laboratory Program. (2018). What does the research say about the initiatives and programs that have the greatest impact on youth employability? Institute of Education Sciences. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/rel/Products/Region/midwest/Ask-A-REL/10171

Mjagkij, N. (2003). Organizing Black America: An encyclopedia of African American associations. Routledge.

Mjagkij, N., & Spratt, M. A. (Eds.). (1997). Men and women adrift: The YMCA and the YWCA in the city. NYU Press.

Nagaoka, J., Farrington, C. A., Ehrlich, S. B., & Heath, R. D. (2015). Foundations for young adult success: A developmental framework. University of Chicago Consortium on School Research.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies). (2015). Identifying and supporting productive STEM programs in out-of-school settings. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21740

———. (2019a). A roadmap to reducing child poverty. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25246

———. (2019b). Fostering healthy mental, emotional, and behavioral development in children and youth: A national agenda. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25201

———. (2019c). Shaping summertime experiences: Opportunities to promote healthy development and well-being for children and youth. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25546

———. (2019d). The promise of adolescence: Realizing opportunity for all youth. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25388

———. (2023). Closing the opportunity gap for young children. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26743

———.(2024a). Promoting learning and development in K-12 out-of-school time settings: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. National Academies Press. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27885/promoting-learning-and-development-in-k-12-out-of-school-time-settings

———. (2024b). Reducing intergenerational poverty. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27058

National Commission on Excellence in Education. (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for educational reform: A report to the Nation and the Secretary of Education. U.S. Department of Education. Government Printing Office.

National Research Council & Institute of Medicine. (2002). Community programs to promote youth development. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10022

Neugebauer, R. (1996). Promising developments and new directions in school-age care. Child Care Information Exchange.

Noam, G. G., & Rosenbaum Tillinger, J. (2004). After-school as intermediary space: Theory and typology of partnerships. After-school worlds: Creating a new social space for development and learning. New Directions for Youth Development, 2004(101), 75–113.

Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education. (2015). The evolution and potential of career pathways. U.S. Department of Education.

Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L. & Rose, T. (2020). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(1), 6–36.

Peterson, T. (2013). Expanding minds and opportunities: Leveraging the power of afterschool and summer learning for student success. Collaborative Communications Group.

Pittman, K. J., & Cahill, M. (1992). Pushing the boundaries of education: The implications of a youth development approach to education. Academy for Educational Development.

Pittman, K. J., & Irby, M. (1996). Preventing problems or promoting development? Forum for Youth Investment.

Ross, M., Kazis, R., Bateman, N., & Stateler, L. (2020). Work-based learning can advance equity and opportunity for America’s young people. Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/20201120_BrookingsMetro_Work-based-learning_Final_Report.pdf

Search Institute. (2007). Developmental assets list. http://www.search-institute.org/developmental-assets/lists

Seitz, S., Khatib, N., Guessous, O., & Kuperminc, G. (2021). Academic outcomes in a national afterschool program: The role of program experiences and youth sustained engagement. Applied Developmental Science, 26(4), 766–784.

Simpkins, S. D. (2015). When and how does participating in an organized after-school activity matter? Applied Developmental Science, 19(3), 121–126.

Sliwa, S. A., Lee, S. M., Gover, L. E., & Morris, D. D. (2022). Peer reviewed: Out of school time providers innovate to support school-aged children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Preventing Chronic Disease, 19.

Stephen, S., & Schillmoeller, S. (1987). Child day care: Selected federal programs. Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress.

Theriault, D. (2018). A socio-historical overview of Black youth development in the United States for leisure studies. International Journal of the Sociology of Leisure, 1, 197–213.

U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Promise neighborhoods: A place and a set of strategies. https://promiseneighborhoods.ed.gov/

YMCA. (n.d.). History of YMCA Anthony Bowen. https://www.ymcadc.org/history-of-ymca-anthony-bowen/

This page intentionally left blank.