The Future of Youth Development: Building Systems and Strengthening Programs (2025)

Chapter: 6 OST Implementation: Program Quality and Experiences

6

OST Implementation: Program Quality and Experiences

Program quality, participation, and engagement are inextricably linked and can drive youth outcomes, as discussed in earlier chapters. Variation in program quality helps to account for differences in effectiveness; the youth development field has focused increasingly on improving the quality of both program design and implementation to best meet participants’ needs. This chapter focuses on program quality in out-of-school-time (OST) settings, including assessment and common indicators of quality; the implementation of quality improvement systems across OST programs, activities, and settings and the organizations that drive quality improvement; and the costs of high-quality OST programs. The chapter then zooms into the programs themselves, summarizing scholarship on the experiences of children and youth that happen in OST programs. Finally, the chapter concludes by describing program quality assessment and improvement initiatives.

OST PROGRAM QUALITY

Numerous studies have found that higher program quality is associated with better participant outcomes (e.g., Christensen et al., 2023; Durlak et al., 2010; Gliske et al., 2021; Kuperminc et al., 2019; Vandell et al., 2022). In the youth development field, quality refers to OST program practices that support programmatic goals and individual outcomes for youth and staff (Palmer et al., 2009). The quality of practices and youth experiences in programs can vary greatly depending on numerous factors, including staff leaders’ experience and skills, environment and resources, and social interactions within the program. Program quality generally includes aspects of

the physical space, psychological safety, structure, adult–youth interaction, and the provision of learning opportunities (Yohalem & Wilson-Ahlstrom, 2010). There is no single way in which the field collectively defines the construct, as evidenced through a variety of operationalizations within research, frameworks, standards, and measures. Variations in how quality is operationalized might be due to (1) differences in practices and desired outcomes among OST programs and (2) evolutions in prioritizing specific themes of quality to better meet the needs of children and youth (Lentz et al., 2024).

Most current quality rubrics or initiatives tacitly take a universal standard or “best practices” approach; that is, they assume a practice affects all children and youth in similar ways and a best practice generally is experienced as such by all. However, individuals may experience programs in ways that differ from other young people or from the “average” experience (Spencer et al., 1997), and dilemmas of practice that are not clearly covered in quality rubrics are common (Larson & Walker, 2010). In addition, Wilson-Ahlstrom and Martineau (2022) argue that quality standards are often developed in ways that are “color neutral” and reflect and reify the dominant culture (Wilson-Ahlstrom & Martineau, 2022). An emphasis on universal standards therefore risks overlooking the specific needs of children and youth from marginalized backgrounds (Wilson-Ahlstrom & Martineau, 2022).

The field operationalizes quality through research and evaluation (e.g., Erbstein & Fabionar, 2019; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2019a) and frameworks, standards, and measures developed by research and capacity-building intermediary organizations (e.g., David P. Weikart Center for Youth Program Quality, 2020; National Institute on Out-of-School Time, 2023). Evaluation practice1 has shaped the field in ways that affect the availability, design, and implementation of OST programs for children and youth from low-income households or marginalized2 communities. Increased emphasis on evaluation that includes program quality (and other potential

___________________

1 Evaluation of OST programs has occurred in three phases: Phase 1, from the founding of the field up to the mid-1990s, was about defining positive youth development in contrast to problem-focused approaches; Phase 2, from the mid-1990s through mid-2010s, included a focus on content and understanding elements of program quality; Phase 3, occurring now, focuses on programs as contexts for development, including better definition of youth development programs, better measurement, and stronger evaluation designs (Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2016).

2 In a scoping review of 50 years of research, Fluit et al. (2024) synthesized an integrated definition of marginalization as “a multifaceted concept referring to a context-dependent social process of ‘othering’ where certain individuals or groups are systematically excluded based on societal norms and values, as well as the resulting experiences of disadvantage” (p. 1). The authors note that both the process and outcomes of marginalization can vary significantly across contexts (Fluit et al., 2024). See Box 1-3 in Chapter 1.

moderators) would enhance understanding of what is happening inside OST programs, helping to discern factors that contribute to program quality, facilitate implementation fidelity, and provide opportunities for continuous quality improvement. OST evaluation includes individual program evaluations; larger, multisite evaluations; and evaluation requirements in funding streams such as 21st Century Community Learning Centers (CCLC) grants. Single-site evaluations usually occur in response to funder requirements, but the resources required for an evaluation are often better aligned with cohort-based or multisite evaluations.

Evaluation is one critical part of the continuous quality improvement process for OST programs. When sponsors require evaluation to be included in program funding, it shapes the nature of activities proposed, leading to the creation or modification of logic models and a focus on the production of evidence. For example, the Advancing Informal STEM Learning program of the National Science Foundation requires that research and innovations developed in this program are evaluated, usually with a focus on fidelity to the proposed activities (Bell et al., 2016). Like the rest of the social services field (McCall, 2009), many OST evaluations focus on youth development outcomes, addressing whether evidence suggests that the program is meeting its intended goals; however, some address program quality.

Assessing Program Quality

Program evaluation can be summative, focused on the results of a program after it concludes (i.e., “Did the program lead to gains for participants in intended or unintended areas?”). Or program evaluation can be formative, using data and data methods to learn about a program under way, typically with the intention of applying that learning to improve the program. Formative program evaluation is usually concerned with or leads back to program quality (i.e., “What are we doing that’s working well and what could be improved?”). Similarly, evaluators sometimes distinguish between process evaluation (focused on implementation) and outcomes evaluation (focused on effectiveness in producing change; e.g., see Patton, 2014). In multisite design it can be challenging to include measures for program quality, as this is a multidimensional factor that is difficult to measure with accuracy. In this context—and with the rise in program quality improvement systems and organizations that support these systems—many OST sites have moved to assessing program quality as a form of evaluation. They typically assess process quality through observational methods and assess participants’ experiences and outcomes through surveys or other methods; they then report these to funders as evaluative evidence.

In the decades since the National Academies published Community Programs to Promote Youth Development (2002), quality improvement tools

and processes that specifically target OST programs have emerged (for a fuller description of this history, see Akiva & Robinson, 2022). Much of this can be traced to the “Features of Positive Developmental Settings” presented in that report (see Table 4-1 in NRC & IOM, 2002, p. 90). Program quality rubrics emerged to assess these features (or variations on these features), usually observationally or through program self-assessment (e.g., “How do we know if a particular setting provides ‘opportunities to belong’”?). Quality improvement processes have been developed alongside these rubrics to help OST sites, often within regional cohorts (i.e., groups of people from programs in the same city or community), to improve program quality systematically.

Several observational rubrics for OST programs were published in the early 2000s. The most used of these are the Youth Program Quality Assessment (Youth PQA) from the David P. Weikart Center for Youth Program Quality3 and the Assessment of Program Practices Tool from the National Institute on Out-of-School Time. Most tools involve observing OST program sessions, then scoring on low-medium-high rubrics. Some tools have shown predictive validity such that higher program quality scores associate with higher scores in survey ratings in various outcome areas (e.g., Smith & Hohmann, 2005; C. Smith et al., 2012; Tracy et al., 2016). Although evidence suggests that quality mediates the impact of OST programs, quality tools are used infrequently in effectiveness research and evaluation.

An important factor in assessing OST program quality and program evaluation is how participatory they are, including the ways in which young people are or are not included in evaluation design. As discussed above and in previous chapters, participatory research is generally defined as research with rather than on people and involves participant involvement in multiple aspects of a study, which can include study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of findings (Cornwall & Jewkes, 1995). Youth participatory research or evaluation is a subset of this approach that specifically involves young people in the various aspects of evaluation. Krenichyn et al. (2007) noted that although positive youth development approaches often promote participation, youth participatory evaluation of programs is rare. Cooper (2017) suggests that participatory evaluation has multiple benefits; it is the right thing to do, it provides better information, and people are more likely to support an evaluation they have been a part of. She notes that it is beneficial for young people and community

___________________

3 Of available observational tools, the Youth PQA has been used in more scholarship and is likely most used in the field. The Youth PQA was tested for validity and reliability in an extensive validation study (Smith & Hohmann, 2005) and the associated continuous improvement process (the Youth Program Quality Intervention) was shown to be effective in a randomized controlled trial (C. Smith et al., 2012). The Youth PQA has since been used in multiple published studies (e.g., Akiva et al., 2013; Beymer et al., 2023; Herman & Blyth, 2016; Jean-Baptiste et al., 2022; Naftzger et al., 2023).

organizations, as it leads to gains both for participants (e.g., “the interests and priorities of the participants shape the evaluation questions”) and for organizations/communities (e.g., “increased likelihood of collecting relevant and appropriate information” [Cooper, 2017, p. 59]).

The youth development field uses research, frameworks, standards, and measures to operationalize quality. These resources often include a series of specific, observable practices (referred to as indicators) that signal quality. In reviewing field-based resources supporting practices—including frameworks, standards, and measures including indicators—that are universal to different program contexts, nationally applicable, commonly measured, and contemporary generally, indicators of quality fall into four broad domains: operations, staffing, environment, and implementation (Lentz et al., 2024). As reviewed by Lentz et al. (2024), quality as it relates to operations includes indicators capturing a program’s scope and design, budget, and data use (Lentz et al., 2024). Indicators related to staffing include job quality and staff practices (Lentz et al., 2024). Common program quality indicators related to environment include safety and wellness; diversity, equity, access, and inclusion; and relationship-building (Lentz et al., 2024). Finally, indicators of implementation include activity planning, youth development practices, and participation (Lentz et al., 2024).

Quality Improvement Systems

Quality rubrics are the basis for quality improvement systems (QISs), which are in operation for OST programs in many locales across the country. A major driver of the development of QISs—from program providers, funders, municipal governments, and advocates—is the aim of providing higher-quality programming at scale, focusing their measurement on group-level data. QISs are designed to align efforts across the youth development landscape (e.g., OST programs, schools, municipal agencies) to set common goals, identify challenges, and target supports to improve OST availability and quality.

Multiple national organizations now provide suites of services (e.g., improvement tools, professional development, coaching) to support OST programs—usually regional cohorts of multiple programs—to improve quality through processes of assessment, improvement planning, coaching, and professional development for practitioners. For example, the Youth Program Quality Improvement system, promoted by the Forum for Youth Investment, operates in nearly every U.S. state and several places internationally (Akiva & Robinson, 2025).

At the program level, a QIS focuses on ensuring that opportunities and experiences provided are adequately serving children and youth from low-income households and marginalized backgrounds (Every Hour Counts, 2021). Program-level QIS functions include collecting data to understand

the nature of programs across the locale, the degree to which they meet the needs and desires of the children and youth they serve, and to what extent content is grounded in the lived experiences of program participants. A QIS at the program level also assesses the quality of program leadership and staff (i.e., management practices and staff competencies). Through collecting and analyzing program-level data, local intermediaries have been able to improve the supports given to programs and program staff in the form of targeted professional development (Gamse et al., 2019). For example, under the Wallace Foundation initiative, “Denver and Saint Paul providers relied on YPQA [Youth Program Quality Assessment] results to inform professional development content for their staff” (Gamse et al., 2019, p. 30).

To date, much of the QIS research and evaluation in OST is focused on group-level data and does not assess intraindividual changes as a result of OST participation. The focus of the QIS at the individual level is on ensuring that children and youth are participating at high levels across the locale and experience engaging activities that drive the development of skills, mindsets, and habits that prepare participants to thrive. Together, the multitiered efforts of QISs in many cities across the United States have led to marked improvements in access and quality in OST, especially for children and youth from low-income and marginalized backgrounds (S. Smith et al., 2012).

Efforts to drive continuous improvement using a QIS have been tested and appear to yield meaningful improvements in OST practices. With a focus on quality assessment, improvement planning, coaching, and staff practices, S. Smith et al. (2012) found that higher-fidelity implementation of continuous improvement practices is related to the quality of instruction. Continuous improvement practices included (1) manager participation in the youth program quality improvement process, (2) a focus on instructional improvement, (3) utilization of continuous improvement practices among managers and staff, (4) improvements in instructional quality, and (5) increases in staff employment tenure.

In summary, QISs are increasingly used across local communities, in line with findings at the state level. They have been shown to support well-coordinated goals, standards, processes for data collection, and associated outcomes—including improvements in management, instruction, and outcomes for children and youth. QISs have also supported municipality-wide improvements in access and quality.

Cost of High-Quality OST Programs

High-quality OST programs have been found to support young people’s learning and development (Lester et al., 2020). However, the youth development field lacks a shared understanding of the resources required

to operate high-quality OST programs. The last comprehensive study of OST program costs was published in 2009 (Grossman et al., 2009). The report quantified three factors in program cost: (1) frequency, duration, and intensity; (2) funding and resource availability; and (3) local context, funding structures, and the needs and interests of children and youth. The report found that hours and wages played primary roles in cost differentiation, which at the time of the report’s release, was on average $7 per hour per individual during the school year; $10 for adolescent programs, and $8 during summer. Grossman et al. (2009) found that the costs of quality OST programs vary greatly, primarily because of program directors’ choices, program structure, activities offered, available resources, and local conditions. Additionally, school-year programs catering to multiple age groups were more expensive than those serving a single age group. Staff wages are a significant cost driver, with teen programs being more costly compared with those for younger participants because of the higher hourly staff wages. Interestingly, teen and nonteen summer programs were less costly hourly than school-year programs because their fixed costs could be spread over more hours (Grossman et al., 2009).

Other research focuses on understanding cost drivers and ways to improve program efficiency, rather than overall OST program cost. These studies identified mechanisms for addressing cost issues, such as hiring staff based on projected daily attendance (Schwartz et al., 2018), limiting the number of sites to control administrative costs, and partnering with community agencies to share facilities (Kanters et al., 2014). Although researchers suggest that these strategies can be effective in the short term, sustaining them can be challenging given the limitations of short-term grants (Afterschool Alliance, 2021; Townsend & Lawrence, 2022).

As many years have passed since the report by Grossman et al. (2009), the estimates have become outdated and do not reflect current conditions and contemporary policy or practice issues. An updated cost study is necessary to reflect advances with respect to quality programming. In addition, the youth development field calls for more specific information about the cost of building high-quality programs and how costs vary according to program model, participant populations, program location, and staffing structures. Recent calls for supporting the youth development workforce underscore the importance of understanding the cost of quality and allocating funding that adequately covers its cost, such as recruiting and retaining direct-service staff (e.g., Afterschool Alliance, 2022; Baldridge et al., 2024; National AfterSchool Association, 2022). Although it is widely acknowledged that OST programs require resources and funding to operate, the literature reveals a need for more empirical studies on the costs associated with operating a high-quality OST program (Lentz et al., 2024).

OST EXPERIENCES: WHAT HAPPENS INSIDE OST PROGRAMS AND ACTIVITIES

This section discusses program features, practices, and processes documented by researchers across the diverse program types and activities serving children and youth from marginalized backgrounds. Qualitative studies that center the voices of participants and staff (alongside nonexperimental quantitative studies) are particularly valuable for understanding what happens inside the “black box” of programs—how participants and staff experience programs, what may be working well, what may need improvement, and where to start making improvements.

This literature builds on the eight features of positive developmental settings offered by the 2002 National Academies report Community Programs to Promote Youth Development: (1) physical and psychological safety; (2) appropriate structure; (3) supportive relationships; (4) opportunities to belong; (5) positive social norms; (6) support for efficacy and mattering; (7) opportunities for skill building; and (8) integration of family, school, and community efforts (NRC & IOM, 2002). As noted earlier, these eight features have come to underpin many practice guides and quality assessments and are foundational to practices today. Since the publication of the 2002 report, qualitative research has captured additional program practices that help create positive developmental settings for children and youth from low-income and marginalized backgrounds: implementing equity practices, such as culturally sustaining practices (e.g., Elswick et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2021, 2022) and critical pedagogies (e.g., Caporale et al., 2016; Ngo, 2017; Park, 2016; Son, 2022; Sulé et al., 2021); building supportive youth–adult relationships (e.g., Brown et al., 2018; Sheltzer & Consoli, 2019); honoring youth voice and choice in structures and programs (e.g., Bulanda & McCrea, 2013; Thompson & Diaz, 2012); and intentionally cultivating a positive and inclusive program climate (e.g., Langhout et al., 2014; Ngo, 2017; Provenzano et al., 2020).

Common in this literature are descriptions of program curricula that are culturally responsive, flexible, and co-created with young people. Similarly, OST programming and curricula are frequently described as project based, grounded in real-world issues, and offering links to young people’s daily lives and opportunities to explore their identities (e.g., McGinnis & Garcia, 2020; Thompson & Diaz, 2012). Common program structures also include collaborative learning, training staff on program curriculum and practices, and flexibility for staff to adjust curricula and activities to meet the needs of the individual participants in their group or program (e.g., Soto-Lara et al., 2021).

Table 6-1 summarizes the eight features of positive developmental settings outlined by NRC and IOM (2002) and adds the importance of culturally sustaining practices and critical pedagogies, and youth voice.

TABLE 6-1 Features of Positive Developmental Settings—Annotated

| Features | Descriptors | Considerations for Supporting Children and Youth from Low-Income and Marginalized Backgrounds: Examples from the Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Physical and psychological safety | Safe and health-promoting facilities, and practices that increase safe peer group interaction and decrease unsafe or confrontational peer interactions |

|

| Appropriate structure | Limit setting, clear and consistent rules and expectations, firm-enough control, continuity and predictability, clear boundaries, and age-appropriate monitoring |

|

| Supportive relationships | Warmth, closeness, connectedness, good communication, caring support, guidance, secure attachment, and responsiveness |

|

| Features | Descriptors | Considerations for Supporting Children and Youth from Low-Income and Marginalized Backgrounds: Examples from the Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Opportunities to belong and the intentional cultivation of a responsive and inclusive* program climate | Opportunities for meaningful inclusion, social engagement, and integration; opportunities for sociocultural identity formation; and support for cultural and bicultural competence |

|

| Social contribution | Young people and community centered, opportunities to contribute using individual and local assets, scaffolded opportunities for leadership |

|

| Support for efficacy and mattering | Youth-based empowerment practices that support autonomy and making a real difference in one’s community; practices that include enabling, responsibility-granting, and meaningful challenge; practices that focus on improvement rather than on relative current performance levels |

|

| Opportunities for skill-building | Opportunities to learn physical, intellectual, psychological, emotional, and social skills; exposure to intentional learning experiences; opportunities to learn cultural literacies, media literacy, communication skills, and good habits of mind; preparation for adult employment; and opportunities to develop social and cultural capital |

|

| Integration of family, school, and community efforts | Concordance; coordination; and synergy among family, school, and community |

|

| Adoption of culturally sustaining practices and critical pedagogies | Opportunities to increase critical consciousness and critical engagement, support for identity development, culturally relevant and responsive practices/pedagogy and programs across different content areas, fostering safe collectives between peers and with adults |

|

| Features | Descriptors | Considerations for Supporting Children and Youth from Low-Income and Marginalized Backgrounds: Examples from the Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Programs and structures that honor youth voice and choice | Opportunities to support youth agency, leadership, and empowerment; shared-decision-making models and youth participatory action; co-designed and co-constructed programs and activities |

|

*As described in the Blue Book (NRC & IOM, 2002):

“How is inclusiveness across cultural groups achieved? Simply bringing different groups into contact with each other does not necessarily lead to mutual understanding and respect; the conditions of contact are critical (Merry, 2000; NRC & IOM, 2000). Experimental studies introducing multiethnic cooperative learning groups have demonstrated that such experiences increase crossethnic group friendships and, in turn, increase a sense of belonging in the school and the classroom (Slavin, 1995).” (p. 9)

SOURCE: Generated by the committee; adapted from NRC & IOM, 2002.

The table also highlights examples from the literature for how each of the 10 features can support children and youth from low-income and marginalized backgrounds.

Culturally Sustaining Practices and Critical Pedagogies

Forming personal identity is a task of development that is particularly salient during adolescence (National Academies, 2019c). As summarized by Coyne-Beasley et al. (2024) and Williams and Deutsch (2016), as young people grow older, they become increasingly aware of and attuned to their social status, and institutions, policies, and practices may reinforce status hierarchies and stereotypes about members of groups that are nondominant or stigmatized in society. Many OST programs specifically aim to provide children and youth a space to explore, understand, and navigate their identities (e.g., Caporale et al., 2016; Pinkard et al., 2017). Some programs draw on critical frames, engaging participants in the interrogation of systems and structures, both historical and contemporary, that impact their lives (e.g., Abraczinskas & Zarrett, 2020; Brown et al., 2018; Caporale et al., 2016; Carey et al., 2021).

Ladson-Billings (2021) describes a focus on culturally relevant learning as a classroom-based pathway for understanding and fostering the competence of children and youth from various racial and ethnic backgrounds. The tenets of culturally relevant learning rest upon ideas of (1) learning; (2) cultural competence of the educators—that is, understanding the contexts in which children and youth are growing and learning, and including these experiences in pedagogical strategies; and (3) the development of participants’ critical consciousness and promoting their ability to see their social conditions, understand what is and is not of their doing, and recognize the interpersonal and larger systems that contribute to their station and well-being, often with a commitment to change (Ladson-Billings, 2021). As documented by García-Coll et al. (1996) and Ladson-Billings (2021), OST programming can reflect the principles of culturally relevant learning in numerous ways, such as building upon strengths-based approaches to recognize participants’ race, language, and heritage in ways that foster their identities (García Coll et al., 1996; Ladson-Billings, 2021). As Gay (2000) describes, such programming uses the cultural characteristics, experiences, and perspectives of racially and ethnically diverse children and youth (that is, their lived experiences and frames of reference) as conduits for developing programming that is more personally meaningful, has higher appeal, and may be learned more easily and thoroughly (Gay, 2000). Numerous qualitative studies of OST programs illustrate the nuanced variation and adaptation of culturally relevant practices in OST programs with and for children, youth, families, and communities.

As described by Barton and Tan (2009) and Ryu et al. (2019), explicitly inviting participants who have been marginalized because of their ethnicity,

language, or nativity to contribute knowledge is a strengths-based strategy that connects participants’ family and learning microsystems. Ryu et al. (2019) explored how Burmese youth who were refugees navigate their identities in OST programs. The research team collected videos of learning processes accompanied by audio recordings of group interactions in an effort to understand how participants made sense of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) content. Analyses focused upon the earlier quarter of the 21 sessions, one-third of which included responsive practices, to best understand the earliest phases of navigating identity and engaging familiar cultural content in understanding science. For example, in learning about climate, participants used the words “zig” and “zag” to take turns sharing and recalled products native to their culture for protecting the skin from the harsh effects of sun. Though trepidatious and less confident early on, the youth engaged and valued each other’s perspectives while learning about the science of climate and weather. Creating a space for children and youth to draw upon their culture in STEM learning illustrates how to integrate “funds of knowledge” with young people who are refugees (Ryu et al., 2019).

Similarly, Yu et al. (2021) characterized culturally responsive programs for Latine youth: (1) promoting an inclusive, safe, and respectful program climate, particularly in regards to culture, language, race, and ethnicity; (2) engaging in personal conversations between staff and youth versus more exclusive and isolating experiences; (3) providing opportunities for mutual learning across diverse cultures and perspectives; and (4) promoting a range of social and emotional skills that honor cultural values about emotional development. Yu et al. (2021) built on previous work by Soto-Lara et al. (2021), who examined culturally relevant approaches to fostering STEM identities for youth who feel stereotyped and excluded from STEM areas by their gender, ethnicity, or race. STEM programming for middle school children was conducted in minority-serving, university-based OST programs (Soto-Lara et al., 2021). In interviews with 28 participants (50% female), the adolescents shared the program processes they thought contributed to their enhanced STEM learning—incorporating advanced math concepts in real-world examples such as real estate investments, and engaging in collaborative learning, campus tours, and informal conversations. This work highlights identity-supporting practices that can contribute to math identities among Latine youth (Soto-Lara et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2021).

In summary, the available qualitative and ethnographic literature highlights innovative, strengths-based approaches for integrating participants’ backgrounds into programming; these approaches can be culturally sustaining for children and youth who are marginalized because of their race, ethnicity, nativity, and/or language. The participants and program leaders taking part in these studies report that culturally relevant pedagogical

approaches can celebrate diversity, help to reduce stereotypes, and foster “learner” identities in topics ranging from science and math to art and literacy (Ryu et al., 2019; Soto-Lara et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2021). While much examination of culturally sustaining practices in OST settings has focused on race and ethnicity, some studies show that these concepts can apply to other marginalized groups; and some studies have examined these tenets for LGBTQ+ youth (Carey et al., 2021; McCormick et al., 2015), bilingual youth (Perry & Calhoun-Butts, 2012; Ryu, 2019), and marginalized gender groups (Schnittka & Schnittka, 2016; Simon et al., 2021). This body of work offers prospects for future research into methods that might be particularly effective for fostering positive effects in OST programs for children and youth from marginalized backgrounds.

Supportive Relationships

Decades of robust literature on child and youth development find that supportive familial, caregiver, and adult relationships play a significant role in fostering positive outcomes for children and youth. They need secure attachment from adults as a foundation for healthy development and strong relationships (National Academies, 2019b,c). Similarly, peers play an important role in youth development (National Academies, 2019c).

Studies suggest that participants value the relationships built with peers, mentors, program staff, and caregiving/helping others. In some cases, these relationships are credited as an important component of the program’s success (e.g., Bulanda & McCrea, 2013; Kamrath, 2019; Kennedy et al., 2016). Both the relational climate (e.g., trust; Meza & Marttinen, 2019) and instrumental features of the relationships (e.g., staff helping with tasks, teaching skills, brokering networks) have been identified in the literature as important (Perry & Calhoun-Butts, 2012; Sheltzer & Consoli, 2019). Study participants, staff, and researchers use phrases such as “comfortable,” “empowering,” “welcoming,” and “family-like” to describe program spaces built through strong relationships between adults and young people and among the young people as peers (e.g., Pavlakis, 2021; Ryu et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2022). Monkman and Proweller (2016), for example, describe the program they studied as offering “space to ‘be,’ space to ‘grow,’ and space to ‘do’” (p. 191). Participants often reported that they could “be themselves” in such OST programs (e.g., Doucet & Kirkland, 2021).

Peer Relationships

Many programs identify the collective relationships they foster among participants as important for their work. Relationships with peers are seen as contributing to positive, trusting, and fun program climates (e.g.,

Chung et al., 2018), and participants report using each other as resources for learning (e.g., Tichavakunda, 2019). Studies have explored how relationships within programs facilitate participation and learning in the program. Participants report that peer relationships influence motivation to join and continue in the program (e.g., Hicks et al., 2022; Vickery, 2014; Whalen et al., 2016). For example, participants in an afterschool physical activity program reported, “For the people that struggle or have challenges [. . .] they see that there’s somebody out there that has the same challenges. So you see you’re not the only one struggling with the same thing” (Whalen et al., 2016, p. 645).

Some programs use a peer-mentoring model, whereby peers or near peers with greater experience or expertise work with less experienced program participants to support their learning (e.g., Clement & Freeman, 2023; Hillier et al., 2019; Robinson-Hill, 2022). For example, the Training Future Scientists program, implemented at a community afterschool program in Chicago, used peer-led cooperative-learning groups and working role models to create authentic science experiences (Robinson-Hill, 2022). Participants reported benefits such as personal growth and development and enhanced peer leadership skills. One peer leader reported that they realized that age does not influence “how much a person can learn, how intelligent a person is, nor the capacity of their mind space” (Robinson-Hill, 2022, p. 128).

Some studies note, however, how peer interactions can reinforce or (re) create social boundaries between identity groups (e.g., Doucet & Kirkland, 2021; Hennessey Elliott, 2020; Schnittka & Schnittka, 2016). That said, most studies emphasize the positive nature of peer relationships, including how young people foster positive social norms that create welcoming environments and how these relationships provide support and motivation for program participants (e.g., Cavendish et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2019; Ryu et al., 2019).

Youth–Adult Relationships

Youth–adult relationships also are often noted as critical processes that contribute to programs’ success. Program staff are often noted as critical for both maintaining the structure of the program (e.g., Bulanda et al., 2013) and fostering supportive relationships with the participants (e.g., Whalen et al., 2016). Adult staff can serve as role models and share their stories with participants to build a sense of identity and relationships (e.g., Lalish et al., 2021; McGinnis & Garcia, 2020; Sheltzer & Consoli, 2019).

Relationships with adult staff are also a mechanism for engaging children and youth in programming (e.g., Marttinen et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2021) and for building trust (e.g., Brown et al., 2018; Meza & Marttinen, 2019).

Some programs prioritize time for staff to get to know participants through both program activities and informal conversations (Marttinen et al., 2021; Soto-Lara et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2021).

Recognizing the critical role of adult staff, some programs specifically hire staff who they feel will be able to foster close and caring relationships with program participants (e.g., Kamrath, 2019). Yu et al. (2021)—in their qualitative study of a high-quality OST STEM program serving middle school–aged Latinx youth from economically underprivileged communities—found that relationships with adult staff from similar backgrounds as the youth was as a common strength. McGovern et al. (2020), moreover, described a weekly youth coalition that organized monthly events in a rural community. McGovern et al. (2020) report that program leaders leveraged shared backgrounds to form meaningful relationships with youth and established trusting relationships with families. The study found that program leaders served as trusted allies with participants and supported the young people in navigating discrimination and developing leadership skills (McGovern et al., 2020).

In some programs, adults purposefully share power with children and youth (e.g., Abraczinskas & Zarrett, 2020; Langhout et al., 2014). In studies of these programs, shared decision-making power between adults and young people has been described as critical for fostering relationship-building between adults and young people (e.g., Anyon et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2018; Bulanda & McCrea, 2013; Whalen et al., 2016).

Several studies also note practices that encourage collaboration between participants and adults beyond staff, such as peer-led discussions and design-based challenges (e.g., Jones & Lynch, 2023; Kennedy et al., 2016; Soto-Lara et al., 2021). These include facilitating connections to wider networks of people and institutions, such as the program bringing in local experts or leaders to speak with participants or links to colleges and universities (e.g., Lalish et al., 2021; Vickery, 2014). For example, Science Club was founded in 2008 as a mentor-based afterschool program for underserved middle school youth in Chicago (Kennedy et al., 2016). Through weekly, inquiry-based, small-group instruction in a dedicated laboratory setting at a Boys & Girls Club, participants build authentic science skills and receive the support of scientist-mentors (i.e., Northwestern University graduate students from a variety of STEM disciplines, including chemistry, biology, engineering, and neuroscience). The relationship between mentor and mentee is bidirectional: mentors teach STEM skills while learning new approaches to science teaching and communicating with the children and youth they serve. According to Kennedy et al. (2016):

Youth focus groups and interviews conducted as part of the project evaluation confirmed Science Club members’ engagement and overwhelmingly positive feelings about their experience. Members clearly identified

themselves as part of an academic, social, and emotional support system that included peers, scientist-mentors, and Science Club staff. In interviews, youth often named the social and supportive environment as an important factor in their enjoyment of Science Club. One youth noted, “They make me feel like I matter.” Another participant said the community is integral in “Pushing me and keeping my drive and that hope, that fire lit, to keep going.” This support played a critical role in participants’ academic and social development in middle school, high school, and beyond. For example, Science Club leaders regularly help students with applications to and full-ride scholarships for selective-enrollment high schools, provide paid “high school mentor” positions to program alumni, and assist college-age alumni in finding summer internships. (p. 6)

Through mentoring models that foster such connections, programs expand the social capital of children, youth, and families in their programs (e.g., Means, 2019). Formal mentorship training for staff, however, has not been widely studied. Hillier et al. (2019) examined mentorship training on program models, goals, and activities; how to manage sessions; effective listening and communication skills; problem-solving; and potential challenges of being a mentor.

In summary, the literature demonstrates the relevance of relationships as a mechanism for learning and engagement. Although relationships as key to high-quality OST programs has been a long-standing focus in the field, few programs appear to include explicit support and time for relationship-building in their activities and structures, nor for training staff on best practices in mentoring and relationship development. This represents an opportunity for further improvement across the field.

Youth Voice, Leadership, and Co-Design

As mentioned in Chapter 2 there is variation in the degree to which youth voice, decision-making, and leadership are prioritized or incorporated into programs or activities, with practitioners and scholars using varied terms for these qualities. However, youth–adult partnership has gained ground as a clear and concise depiction. Zeldin et al. (2013) define youth–adult partnership as the practice of

(a) multiple youth and multiple adults deliberating and acting together, (b) in a collective [democratic] fashion (c) over a sustained period of time, (d) through shared work, (e) intended to promote social justice, strengthen an organization and/or affirmatively address a community issue. (p. 388)

Youth–adult partnerships have been studied across multiple contexts, but primarily in OST programs. Programs can enact youth–adult partnerships (i.e., incorporate youth voice) in a number of ways: offering participants choices about which activities to participate in, inviting children and

youth to provide formal or informal feedback on program design, and offering an opportunity for shared decision-making with adults and hands-on leadership development (Akiva & Petrokubi, 2016). Scholars have noted that facilitating youth–adult partnerships is not simply a matter of letting young people lead (Camino, 2015), but it requires skill and strategy from adult facilitators—this has been referred to as “leading from behind” (Larson & Angus, 2011, p. 84). Scholars have also identified challenges and tensions in supporting young people as they assert power and agency (Medina et al., 2020; Serrano et al., 2022).

As a form of youth–adult partnership, programs engaging preteens and adolescents can offer opportunities for children and youth to engage in peer mentoring/teaching and leadership (Akiva & Petrokubi, 2016), lead activities or programs (Delgado, 2004; Kruse, 2019), and serve on executive or advisory boards (Zeldin, 2004). In these settings, younger children can observe older youth in leadership activities, such as mentoring, teaching, and organizing, which models future roles for younger children. Developmentally appropriate youth–adult partnership efforts in OST programs may include participatory action research, program evaluation, and social entrepreneurship.

A growing body of literature recognizes that young people’s developing competencies in flexible problem-solving, their awareness of and concern with others, and their openness to exploration and novelty make adolescence an opportune time for supporting agency and leadership and promoting engagement—OST settings offer an opportunity for children and youth to develop such skills (National Academies, 2019a). OST scholarship identifies programs with positive relationships on youth empowerment and leadership, specifically programs that include a youth participatory action research (YPAR)4 component (e.g., Abraczinskas & Zarrett, 2020; Anyon et al., 2018) and those that integrate youth voice, decision-making, and/or leadership (e.g., Akiva & Petrokubi, 2016; Langhout et al., 2014).

For example, a group of Indigenous Oaxacan youth and young adults, with the support of diverse adults, led a two-year YPAR project to document the civic engagement pathways of migrant and Indigenous youth in California (Oaxacalifonia Reporting Team, 2013). Youth explored questions on gender roles in civic participation, and the unique cultural and linguistic situation of Oaxacan youth, who navigate Oaxacan culture visà-vis Mexican, Mexican American, and other American cultures. Youth in the research team were bilingual or trilingual—some spoke an Indigenous language at home, Spanish with friends, and English in schools. Its research report describes how the program provided an opportunity for youth to safely develop an understanding of their identity and explore intra- and interethnic dynamics that support or hinder civic participation and social mobility (Oaxacalifonia Reporting Team, 2013).

___________________

In many programs, young people are considered co-constructors of activities and knowledge, contributing to feelings that the programs are youth-centered spaces. Participants often contrast this with other spaces in their lives (e.g., Yu et al., 2022). Founding OST programs in youth development and cultural competence can contribute to a common view of young people as assets and a focus on their holistic development. At the same time, challenges can arise when partners do not share those views (e.g., if some program partners hold a more deficit view of young people and their families; see, e.g., Pavlakis, 2021). Box 6-1 summarizes perspectives from young people who shared with the committee their personal experiences in an OST program that serves low-income communities or households.

THE ROLE OF INTERMEDIARIES IN SUPPORT OF PROGRAM QUALITY

Intermediaries play a strong role in supporting program quality and the practices described in this chapter that underpin quality implementation. Intermediaries support quality through creating common quality practices and metrics across systems, standing up quality standards or competencies via the design of shared data systems (i.e., management information systems), and through shared data use and evaluation.

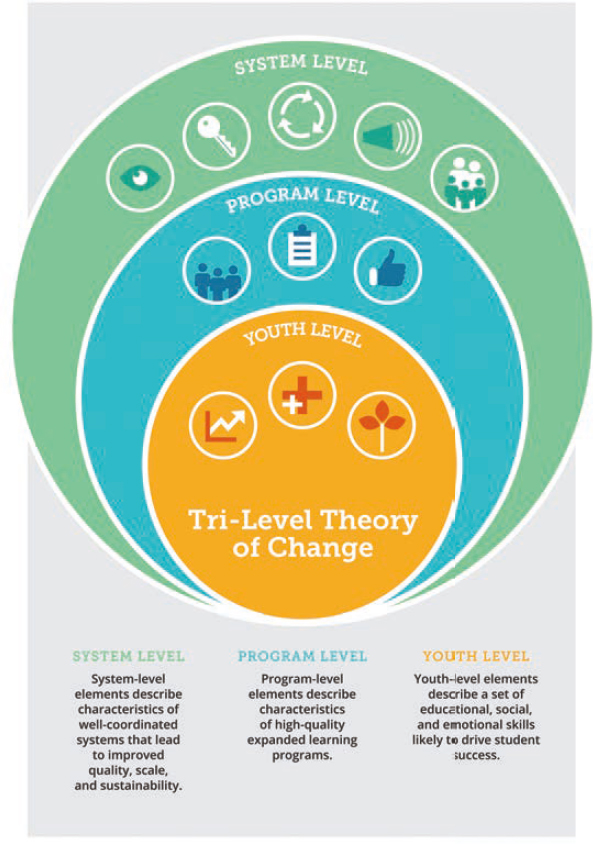

Every Hour Counts (2021) released an updated continuous improvement framework that provides a high-level perspective on QISs. Developed by a group of leaders of OST intermediaries across the United States, the framework organizes outcomes into three levels: system, program, and youth (see Figure 6-1). This organization provides a useful way for OST program leaders to assess their current practices, set goals, and implement targeted strategies for improvement. Local municipalities that have developed QISs typically assess quality at all three levels.

At the systems level, QISs are concerned primarily with ensuring that the OST system is coordinated in a way that ensures continuous improvements in quality and quality at scale, and in a way that ensures that investments and outcomes across OST programs are sustainable. OST intermediaries overseeing a QIS coordinate efforts to (1) create common goals; (2) define standards for the field; (3) adopt a program quality assessment tool; and (4) develop and oversee a management information system as a means of achieving those goals. Systems-level considerations also include data collected on cost to determine what financial resources are required to meet the goals set forth by the OST intermediary and their partners and identifying program locations to assess the degree to which all children and youth have access to high-quality programming.

For example, under the Wallace Foundation’s Next Generation Afterschool System Building Initiative, system leaders noticed a sharp decline in

BOX 6-1

Young People’s Experiences in OST Programs

The committee held two information-gathering sessions in February and April 2024, during which young people shared personal stories of their time in an out-of-school-time (OST) program. They were asked to share how they got involved in the program, what they enjoyed about the program, and what their participation in the program has meant for their lives.

When asked to share what they like most about their programs, young people often spoke about the variety of activities and clubs within their programs and the opportunities to grow. For example, a young adult from South Dakota noted her enthusiasm to participate in an entrepreneurship program, where she learned how to run her own business, create a resume, and practice interviewing skills. Others shared how programs offered them a chance to support their communities and families. For example, a high schooler from Arizona shared that through his 4-H program, he is engaged in community volunteer projects that support the Hopi Reservation where he lives. A high schooler from Georgia said that one of her favorite things about her program is that it offers a platform for participants and families, largely from an immigrant and refugee community, to have their voices heard. The program elevates the voices of independent young people.

Speakers shared that in their programs they express themselves through painting, sewing, and graphic design, and they work on soft skills such as public speaking, multitasking, managing projects, and networking. One middle schooler added, “There are so many different ways, so many different things I’ve learned from this program that can really help me in my future of going to high school and college.”

These young people spoke time and again of engagement, encouragement, and support from staff and peers as crucial to their positive experiences, often referring to them as a family. High school students from the Washington, DC, area spoke about their programs as a “second home” and “a place where you can come and be safe just in case something’s happening outside of the program.” Another noted that she loves the “positive mentorship and having people who actually care.” A high schooler from Florida shared that program staff “give us courage and encourage us to be better just by showing us love,” with staff serving as role models in his life.

Finally, the young people talked about the impacts of their experiences on their perspectives. One speaker said that his experiences “showed me there is a different side of the world when you do right.” Another said, “they have opened me to so many experiences and opportunities that I still talk about to this day.” A high schooler from Washington, DC, said that the experiences he has had in his program “changed my viewpoint on a lot of things, a lot of people, and it has changed the way I think before I react to certain situations. [...] Your thoughts, words, and actions will determine your destiny, and Life Pieces [the program] has taught me that. So, I can use that in what I say, what I do, and how I react.”

SOURCE: Every Hour Counts, 2021.

summer learning opportunities in a high-poverty neighborhood in a particular city, based on data uploaded by program providers (Gamse et al., 2019). Although the decline in availability was attributed to temporary issues with facilities, the prompt availability of data made it possible for the intermediary to notify the city about the broader problem. In response, OST system leaders collaborated with city agencies and private funders to create a priority list of 15 neighborhoods. Their approach was to focus on these communities first and then expand their programming and impact from there (Gamse et al., 2019).

In 2010, RAND published a study of a prior Wallace Foundation initiative intended to support the development of a QIS in each of five cities (McCombs et al., 2010). Although the cities took varied paths toward developing a QIS, they generally followed a parallel model of developing a common vision and goals, developing or adopting standards, and adopting a quality assessment tool. A primary goal of this initiative was to develop a data system that could accurately monitor participation across demographic characteristics to understand who was attending OST programming and to what degree. In the years since the initiative, many more local intermediaries have developed and used QISs to support access and quality improvements.

Program Quality Standards

Many intermediaries that oversee OST programs use quality standards. These standards are the measures or indicators of a high-quality program, ideally reflective of the current evidence on best practices and related outcomes, as well as specific community needs (American Institutes for Research, n.d.). Of central focus for a local intermediary creating or adopting quality standards is ensuring that children and youth are attending high-quality, safe, supportive OST programs with clearly defined and measurable goals and outcomes (Russell & Little, 2011). These quality standards are typically derived from existing research and already existing standards from states and other locales. Local quality standards for OST primarily serve the following purposes (Nevada Interim Out-of-School Time Task Force, 2012):

- Provide a common language to define quality in OST programs and settings;

- Define quality OST programming specific to that locale;

- Support the professionalization of the field;

- Serve as a foundation for program and practice decisions;

- Provide a framework for evaluation and continuous improvement; and

- Inform various stakeholders, including the general public, about the quality of available programs. (American Institutes for Research, 2020; Russell & Little, 2011)

A survey of OST coordinating entities found that a majority (62%) of municipalities surveyed were using quality standards (Simkin et al., 2013). Nearly all (39 out of 43) that reported using quality standards also had an associated assessment tool. At the state level, 42 states have developed quality standards and guidelines (American Institutes for Research, 2020). Many local OST intermediaries adopt or adapt their state’s quality standards.

Standards typically contain a set of categories, with elements providing detail about necessary or desired components and specific standards set

for each element. Common categories for quality standards include safety, health, and well-being; environments; supportive relationships; program management; program activities; staffing and professional development; and program evaluation. Reflecting growing evidence from the literature on the science of learning and development (Cantor et al., 2020), and based on community need (e.g., shifting demographics), some municipalities have also followed the lead of their state’s coordinating entity in adopting standards detailing social and cultural competencies.

The process for the development of local quality standards can vary in part based on the governance structure of OST programs in that locale. In some cases, an OST governing body representing a larger municipality in the state has partnered with the state’s governing body to draft both the municipality and the state’s standards. This is done to ensure alignment and to provide an opportunity to drive the adoption of standards across the state. For example, in Louisville, Kentucky, two members from a statewide organization served on the local committee that developed quality standards (Starr et al., 2016). This led to the creation of city-specific standards, as well as an eventual set of standards for the state level (Kentucky Out-of-School Alliance, 2011). Many cities followed a similar path in the development of their standards. For example, in 2006, Grand Rapids, Michigan, convened a group of community partners who were part of the Expanded Learning Opportunities Network to review the current research on OST practices and outcomes and existing OST standards, in order to ensure theirs reflected the current evidence. The National AfterSchool Association5 Standards were primary artifacts used to develop standards for OST programs in Grand Rapids. Community members and leaders were engaged to review and provide feedback on the standards before they were finalized (Spooner, 2011). Similarly, the Tulsa Opportunity Project—the intermediary coordinating OST efforts for the city of Tulsa, Oklahoma—convened program providers, the Tulsa City School District, and city agencies to draft the standards. Community organizations and individual members were convened to discuss and provide critical feedback on the standards prior to their codification.

In recent years, recognizing the emerging evidence on the central importance of context and culture in learning and development, a few state intermediaries, including School’s Out Washington (2014), have developed standards and assessment tools on cultural competence and relevance. Given that many local intermediaries adopt or adapt state standards, an increase is likely in the creation of standards for cultural relevance and competence in OST programs in local communities.

___________________

5 At the time, the National Afterschool Association was known as the National School-Age Care Alliance.

Management Information Systems

Gamse et al. (2019) is one of the more comprehensive reports on local efforts to utilize data to support OST program access and quality improvements. In the Next Generation Afterschool System-Building Initiative, the Wallace Foundation chose cities based on strong mayoral leadership and meaningful local investment in youth development. Before the initiative, cities rarely collected basic information, such as the number of participants participating in local OST programs. By 2016, all participating cities had created management information systems (MISs) to reliably collect and store data, and to make those data usable for analysis and reporting (Gamse et al., 2019). In observing this initiative, Gamse et al. (2019) identified three types of investment—people, processes, and technology—that are key to developing capacity to collect and use data for systems-level improvement. The initiative also demonstrated key system activities (Gamse et al., 2019):

- “Define data elements collectively across all stakeholders.

- Create staff position(s) focused on monitoring data accuracy and quality.

- Build data entry and analytic capacity and confidence through professional development (PD) and other trainings focused on data use.

- Provide diverse formats of PD to reach and engage wide range of system users with differential technological and data savvy.

- Collect data systematically from participating providers.

- Review data elements to assess usefulness (e.g., dosage and retention at the individual level may yield more useful information than average daily attendance rates).

- Leverage use of standardized reports and dashboards to make data available and accessible.

- Pilot planned system changes with a smaller group of OST providers before implementing network-wide” (p. 16).

Municipalities developing or selecting an MIS have typically employed one of three strategies based on the degree to which an MIS or other data system was already being utilized. Cities studied as part of the Next Generation Afterschool System-Building Initiative convened partners to discuss the development and use of an MIS. Where an MIS had not existed previously, partners discussed existing data and data uses and debated what data elements would be necessary. Where an MIS did already exist, discussions focused on refinement rather than a wholesale rebuild. Among the eight cities, data initially selected for inclusion in the MIS were program attendance, program quality, school data, and youth development and social and emotional learning measures (Gamse et al., 2019).

Data and Evaluation

Intermediaries collect a variety of data related to individuals, program quality, and community assets and challenges regarding youth development in their community. Intermediaries use these data to evaluate and improve OST program quality and overall system health. And agencies use these data to make informed policy and practice decisions to support high-quality programming. Many local intermediaries have moved toward results-based decision-making6—using youth development outcomes to determine the necessary combination and intensity of supports that will yield high-quality programs. More advanced data systems have allowed for data to be used beyond basic accountability to support continuous improvement. Where capacity exists, local intermediaries conduct their own evaluations of the OST system and individual programs. Where internal capacity is lacking, cities also leverage relationships with local colleges and universities to conduct evaluations. Generally, intermediaries use data to

- Track attendance and participation (to support access, enrollment, and quality improvements);

- Assess the needs of children and youth, families, and communities;

- Develop, adapt, and implement a municipality-wide program quality assessment tool;

- Conduct and support program- and city-level evaluation efforts;

- Develop common, systems-level outcome measures and indicators; and

- Drive continuous improvement efforts.

Training is afforded to OST organizations in many communities by the local intermediary on both the purposes of collecting data and the actual process for data collection, including basic data collection practices, how to accurately enter data into the system, and ensuring data privacy. To maintain data quality, intermediaries have developed data monitoring processes that include “common definitions of indicators, standardizing processes and timelines for data entry and cleaning, and giving feedback to providers about the data that had been entered (e.g., timeliness, missing or incorrectly entered information)” (Gamse et al., 2019, p. 12).

One common challenge noted by municipalities in collecting data relates to accessing school-related data. The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act requires programs to obtain parental consent to access data. Local intermediaries typically enter into agreements with OST providers, school districts, and cross-sector partners to share data. These agreements are central to a robust data system, specifying who is formally part of the

___________________

6 The absence of information in research and program evaluation on youth-specific change can place constraints on results-based decision-making.

OST system and who can access and use the data. To address this yearly challenge, some cities have adjusted policies so that parents need to opt their child in only once throughout their educational career.

CONCLUSION

The youth development field has coalesced around the importance of OST program quality, as evidenced by the many research syntheses, frameworks, standards, and measures described in this chapter. Common indicators of quality across OST settings can include operations, staffing, environment, and implementation. However, how the field names, defines, and measures quality varies, as do the common indicators that are prioritized. Most quality approaches take a universal, best-practice approach that, in most cases, is not explicit about barriers that disproportionally affect low-income and marginalized children and youth. Research is needed that examines how traditional-standards approaches may affect cultural practices and participation, as are thoughtful critiques of the dominant quality approaches.

The committee’s review of qualitative research captured program practices that contribute to the creation of positive developmental settings for children and youth from marginalized backgrounds. Common in this literature are descriptions of program activities that are culturally responsive and co-created with young people, which are critical additions to the features of developmental settings that have emerged since the 2002 National Academies report (NRC & IOM, 2002).

Furthermore, recent scholarship highlights how historical notions of quality—particularly as articulated in existing frameworks, standards, and measures—fail to account for the important role of equitable learning environments for children and youth from low-income and marginalized backgrounds. That is, environments where all students have equal access to learning opportunities, regardless of their background or abilities, and where the program actively works to address individual needs to ensure all students can reach their full potential (see, e.g., Baldridge et al., 2024; Wilson-Ahlstrom & Martineau, 2022). Many authors highlight ways in which critical approaches to positive youth development can be integrated into programs more intentionally (Case, 2017; Imani-Fields et al., 2018; McDaniel, 2017; Tyler et al., 2020; Wilson-Ahlstrom & Martineau, 2022). These conversations can shape how program quality is defined and operationalized in OST programs. Future research will need to consider these principles in definitions and measurement of quality.

Conclusion 6-1: Adopting culturally sustaining practices and critical pedagogies, building supportive relationships with program peers and staff, honoring youth–adult partnerships, and intentionally cultivating

a positive and inclusive program climate are key features of positive developmental settings and contribute to program quality.

Conclusion 6-2: More research is needed to explore associations between specific indicators of quality and outcomes, and to provide additional guidance for focusing on or prioritizing elements of quality to improve outcomes for all children and youth.

REFERENCES

Abraczinskas, M., & Zarrett, N. (2020). Youth participatory action research for health equity: Increasing youth empowerment and decreasing physical activity access inequities in under-resourced programs and schools. American Journal of Community Psychology, 66(3–4), 232–243.

Afterschool Alliance. (2021). The evidence base for afterschool and summer. https://after-schoolalliance.org/documents/The-Evidence-Base-For-Afterschool-AndSummer-2021.pdf

———. (2022). Where did all the afterschool staff go? https://afterschoolalliance.org/documents/Afterschool-COVID-19-Wave-6-Brief.pdf

Akiva, T., Cortina, K. S., Eccles, J. S., & Smith, C. (2013). Youth belonging and cognitive engagement in organized activities: A large-scale field study. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 34(5), 208–218.

Akiva, T., & Petrokubi, J. (2016). Growing with youth: A lifewide and lifelong perspective on youth-adult partnership in youth programs. Children and Youth Services Review, 69, 248–258.

Akiva, T., & Robinson, K. H. (Eds.). (2022). It takes an ecosystem: Understanding the people, places, and possibilities of learning and development across settings. Information Age Publishing.

Akiva, T., & Robinson, K. H. (2025). Program quality: Why it matters and how to strengthen it. In M. E. Arnold & T. M. Ferrari (Eds.), Positive youth development: Advancing responsible adolescent development (pp. 117–133). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-85110-0_7

American Institutes for Research. (n.d.) Quality standards, building quality in afterschool. https://www.air.org/project/building-quality-afterschool/quality-standards

———. (2020). Landscape of Quality survey results: 50 State Afterschool Network. https://indd.adobe.com/view/16eadbe4-d565-47fc-a012-7d4e93593666

Anyon, Y., Kennedy, H., Durbahn, R., & Jenson, J. M. (2018). Youth-led participatory action research: Promoting youth voice and adult support in afterschool programs. Afterschool Matters, 27, 10–18.

Baldridge, B. J., DiGiacomo, D. K., Kirshner, B., Mejias, S., & Vasudevan, D. S. (2024). Out-of-school time programs in the United States in an era of racial reckoning: Insights on equity from practitioners, scholars, policy influencers, and young people. Educational Researcher, 53(4). https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X241228824

Barton, A. C., & Tan, E. (2009). Funds of knowledge and discourses and hybrid space. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 46(1), 50–73.

Bell, S. H., Olsen, R. B., Orr, L. L., & Stuart, E. A. (2016). Estimates of external validity bias when impact evaluations select sites nonrandomly. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 38(2), 318–335.

Beymer, P. N., Robinson, K. A., Naftzger, N., & Schmidt, J. A. (2023). Program quality, control, value, and emotions in summer STEM programs: An examination of control-value theory in an informal learning context. Learning Environments Research, (26), 595–615.

Brown, A. A., Outley, C. W., & Pinckney, H. P. (2018). Examining the use of leisure for the sociopolitical development of Black youth in out-of-school time programs. Leisure Sciences, 40(7), 686–696.

Bulanda, J. J., & McCrea, K. T. (2013). The promise of an accumulation of care: Disadvantaged African-American youths’ perspectives about what makes an after school program meaningful. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 30, 95–118.

Bulanda, J. J., Szarzynski, K., Siler, D., & McCrea, K. T. (2013). “Keeping it real”: An evaluation audit of five years of youth-led program evaluation. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 83(2–3), 279–302.

Camino, L. (2005). Pitfalls and promising practices of youth-adult partnerships: An evaluator’s reflections. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(1), 75–85.

Cantor, P., Darling-Hammond, L., Little, B., Palmer, S., Osher, D., Pittman, K., & Rose, T. (2020). How the science of learning and development can transform education. Science of Learning and Development Alliance. https://soldalliance.org/wp-content/2021/12/SoLD-Science-Translation_May-2020_FNL.pdf

Caporale, J., Romero, A., Fonseca, A., Perales, L., & Valera, P. (2016). After-school youth substance use prevention to develop youth leadership capacity: Tucson Prevention Coalition Phase 1. In A. J. Romero (Ed.), Youth-community partnerships for adolescent alcohol prevention (pp. 63–83). Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26030-3_4

Carey, R. L., Akiva, T., Abdellatif, H., & Daughtry, K. A. (2021). ‘And school won’t teach me that!’ Urban youth activism programs as transformative sites for critical adolescent learning. Journal of Youth Studies, 24(7), 941–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2020. 1784400

Case, A. D. (2017). A critical-positive youth development model for intervening with minority youth at risk for delinquency. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(5), 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000273

Cavendish, L. M., Vess, S. F., & Li-Barber, K. (2016). Collaborating in the community: Fostering identity and creative expression in an afterschool program. Journal of Language and Literacy Education, 12(1), 23–38.

Christensen, K. M., Kremer, K. P., Poon, C. Y., & Rhodes, J. E. (2023). A meta-analysis of the effects of after-school programmes among youth with marginalized identities. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2681

Chung, H. L., Jusu, B., Christensen, K., Venescar, P., & Tran, D. A. (2018). Investigating motivation and engagement in an urban afterschool arts and leadership program. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(2), 187–201.

Clement, W., & Freeman, S. F. (2023). Developing inclusive high school team sports for adolescents with disabilities and neurotypical students in underserved school settings. Children & Schools, 45(2), 88–99.

Cooper, S. (2017). Participatory evaluation in youth and community work: Theory and practice. Routledge.

Cornwall, A., & Jewkes, R. (1995). What is participatory research? Social Science & Medicine, 41(12), 1667–1676.

Coyne-Beasley, T., Miller, E., & Svetaz, M. V. (2024). Racism, identity-based discrimination, and intersectionality in adolescence. Academic Pediatrics, 24(7), S152–S160.

David P. Weikart Center for Youth Program Quality. (2020). Youth program quality intervention. The Forum for Youth Investment. https://forumfyi.org/weikartcenter/ypqi/

Delgado, M. (2004). Social youth entrepreneurship: The potential for youth and community transformation. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Doucet, F., & Kirkland, D. E. (2021). Sites of sanctuary: Examining Blackness as “something fugitive” through the tactical use of ethnic clubs by Haitian immigrant high school students. Journal of Adolescent Research, 36(6), 615–653.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3–4), 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9300-6

Elswick, S., Washington, G., Mangrum-Apple, H., Peterson, C., Barnes, E., Pirkey, P., & Watson, J. (2022). Trauma healing club: Utilizing culturally responsive processes in the implementation of an after-school group intervention to address trauma among African refugees. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 1–12.

Erbstein, N., & Fabionar, J. O. (2019). Supporting Latinx youth participation in out-of-school time programs: A research synthesis. Afterschool Matters, 29, 17–27. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1208384.pdf

Every Hour Counts. (2021). Putting data to work for young people: A framework for measurement, continuous improvement, and equitable systems. https://wallacefoundation.org/sites/default/files/2023-08/Every-Hour-Counts-Measurement-Framework.pdf

Fenzel, L. M., & Richardson, K. D. (2018). Use of out-of-school time with urban young adolescents: A critical component of successful NativityMiguel schools. Educational Planning, 25(2), 25–32.

Fluit, S., Cortés-García, L., & von Soest, T. (2024). Social marginalization: A scoping review of 50 years of research. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–9.

Fuller, R. D., Percy, V. E., Bruening, J. E., & Cotrufo, R. J. (2013). Positive youth development: Minority male participation in a sport-based afterschool program in an urban environment. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 84(4), 469–482.

Gamse, B. C., Spielberger, J., Axelrod, J., & Spain, A. (2019). Using data to strengthen afterschool planning, management, and strategy: Lessons from eight cities. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

García Coll, C., Crnic, K., Lamberty, G., Wasik, B. H., Jenkins, R., Garcia, H. V., & McAdoo, H. P. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

Gliske, K., Ballard, J., Buchanan, G., Borden, L., & Perkins, D. F. (2021). The components of quality in youth programs and association with positive youth outcomes: A person-centered approach. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105696.

Grossman, J. B., Lind, C., Hayes, C., McMaken, J., & Gerick, A. (2009). The cost of quality out-of-school-time programs. Public/Private Ventures & The Finance Project. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/documents/the-cost-of-qualityof-out-of-school-time-programs.pdf

Harrison, D. (2023). De-centering deficit frameworks and approaches: The mentor/mentee relationship in an afterschool tutoring program. The Urban Review, 55(4), 417–432.

Hennessy Elliott, C. (2020). “Run it through me:” Positioning, power, and learning on a high school robotics team. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 29(4–5), 598–641.

Herman, M., & Blyth, D. (2016, June). The relationship between youth program quality and social & emotional learning (Youth Development Issue Brief). University of Minnesota Extension.

Hicks, T. A., Cohen, J. D., & Calandra, B. (2022). App development in an urban after-school computing programme: A case study with design implications. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 31(2), 217–229.

Hillier, A., Ryan, J., Donnelly, S. M., & Buckingham, A. (2019). Peer mentoring to prepare high school students with autism spectrum disorder for college. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 3(4), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-019-00132-y

Holleran Steiker, L. K., Hopson, L. M., Goldbach, J. T., & Robinson, C. (2014). Evidence for site-specific, systematic adaptation of substance prevention curriculum with high-risk youths in community and alternative school settings. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 23(5), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/1067828X.2013.869141

Imani-Fields, N., Moncloa, F., & Smith, C. (2018). 4-H social justice youth development: A guide for youth development professionals. University of Maryland and University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources.