The Future of Youth Development: Building Systems and Strengthening Programs (2025)

Chapter: 2 OST Theories

2

OST Theories

Children and youth live, play, learn, and grow in and across multiple settings. While learning is commonly thought of as occurring in schools, an ecosystem of people, places, and possibilities constitute an environment full of learning and development opportunities for children and youth, both in and outside of school (Akiva et al., 2022). Young people can have positive developmental experiences, for example, at home, libraries, and parks; with peers, mentors, and teachers; and on their own (e.g., daydreaming, playing, hiking). Academic theories explain the intersections within this ecosystem between settings, actors, and experiences and how they contribute to a young person’s learning and development.

This chapter introduces a sample of theories, theoretical frameworks, and models that underpin young people’s learning and development in out-of-school-time (OST) systems and settings. First, developmental theories describe how individual young people may learn and grow within programs. Second, ecological theories consider what activities matter for a young person and how OST settings interact1 with other important contexts in their life.

There is no singular conceptual model on how children and youth learn and develop. The committee thus presents a contribution to the extant

___________________

1 This report uses interact and interaction to describe youth–adult, peer–peer, or youth–context relations. As there is potential for confusion with the statistical concept of interaction (where the effect of one causal variable on an outcome is shaped by a second causal variable [Cox, 1984]), some scholars argue for the use of co-act for these relations (e.g., Lerner, 2021). However, the committee opted to use interact because of its common usage in scholarly and practical OST contexts.

literature in compiling theories and models relevant to youth development and OST programs. These theories lay a foundation for the report’s later discussions, as their expansion and progression have informed how the youth development field approaches programs and the tools and trainings that are used to support program quality (discussed in more detail in Chapter 6).

DEVELOPMENTAL THEORIES: UNDERSTANDING HOW A YOUNG PERSON MAY LEARN AND GROW IN OST SETTINGS

Scholarship on youth development and OST programs occurs across multiple fields of study, including education, social work, and leisure studies, and the majority has occurred from the perspective of developmental science. For example, research in developmental psychology describes increases in autonomy in early and middle adolescence, which can lead to greater interest in and capacity for leadership in OST settings (Larson & Hansen, 2005; Mahoney et al., 2009).2 As OST attendance is voluntary, several scholars have applied motivation theories to OST contexts, particularly self-determination theory (Berry & LaVelle, 2013; Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000; Faust & Kuperminc, 2020; Jones et al., 2021) and expectancy-value theory (Dawes & Larson, 2011; Sjogren et al., 2023; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). In leisure studies, the theoretical approach of the leisure constraints theory (developed to explain adult leisure activity choices) sheds further light on voluntary attendance, considering intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural constraints (Godbey et al., 2010). While these theories contribute to understanding, the predominant home of OST research is developmental science.

Youth development and the influence of OST contexts is complex. Many modern OST theories help capture development, describing the complex, bidirectional processes (i.e., context affects young people and young people affect context in dynamic and nonlinear ways) that transpire in relational, developmental systems. In such a system, each young person interacts with and develops in multiple, dynamic contexts. The ever-changing nature of youth development, coupled with the multifaceted contextual influences, argue that each individual’s developmental path is going to be somewhat unique. In other words, “human development always involves specific outcomes in specific individuals occurring in specific places at

___________________

2 Numerous past reports of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) have reviewed the literature on the developmental stages of children and youth, and the developmental needs that support their thriving (see, e.g., National Academies, 2019a,b,c); therefore, this report summarizes that literature only briefly and as it pertains to OST.

specific times in specific ways” (Lerner & Bornstein, 2021, pp. 1–2). This is known in developmental science as the specificity principle (Bornstein, 2017). Although there are some universal underlying principles, individuals’ unique experiences may differ greatly, even in shared contexts. For example, people likely agree that OST activities matter for youth development, but which experiences in which OST activities matter for which outcomes and for which young people? The theories and models presented in this chapter provide insight into this question.

Although these theories acknowledge differing individual experiences, most quantitative research in OST relies on averaging data across groups, which can produce misleading conclusions obfuscating individual variation (e.g., Speelman & McGann, 2013). The results of such research can be limiting for a number of reasons. First, averaging data across groups can create conclusions that do not apply to any real individual (Rose, 2016). Second, within-person fluctuations in survey responses (typically treated as “error”) are much more common and substantive than researchers typically acknowledge; an individual’s responses to survey items and scales can vary substantially from day to day (Hamaker et al., 2018; Moelnaar, 2004; Ram et al., 2005). Third, the specificity principle suggests that the subject of this report—young people from low-income backgrounds or those with intersecting characteristics of marginalization3—may experience programs differently from group averages. Thus, research that adheres to the specificity principal, such as ideographic approaches, is warranted. The committee builds on these issues in Chapter 7.

General Developmental Models

General developmental models have been used to understand and explain the role of OST programs in a young person’s life. General indicates models that are relevant but not specific to OST. These are theoretical pictures of how a young person develops. As all contemporary developmental theories acknowledge the important role of context in development (Lerner et al., 2023), these models have been used to shed light on how time spent in OST settings can affect development.

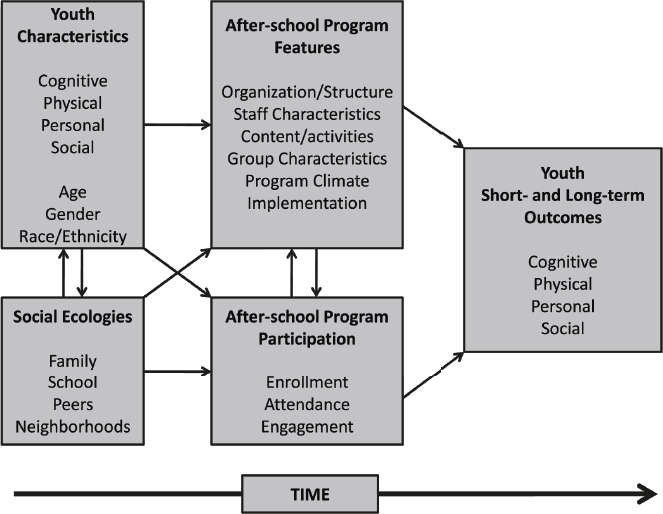

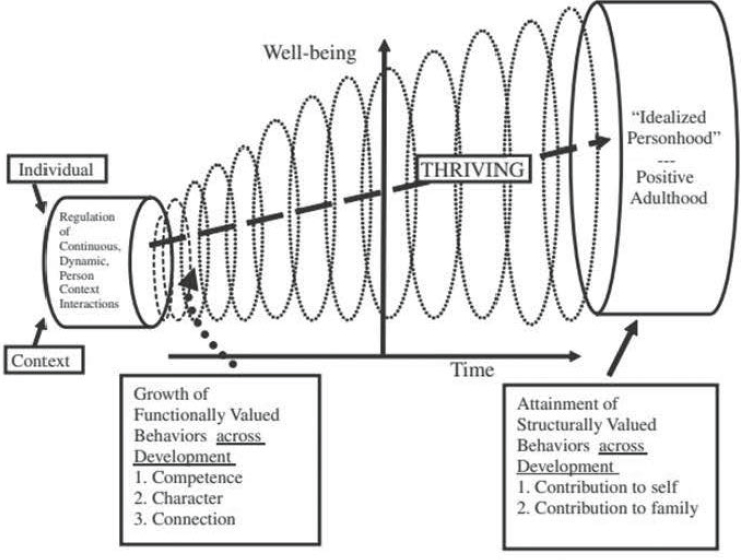

In Lerner’s original thriving model, OST programs are considered one of many factors affecting development (see Figure 2-1; Lerner et al., 2005a,b). Although this model has evolved and become more specified,

___________________

3 In a scoping review of 50 years of research, Fluit et al. (2024) synthesized an integrated definition of marginalization as “a multifaceted concept referring to a context-dependent social process of ‘othering’ where certain individuals or groups are systematically excluded based on societal norms and values, as well as the resulting experiences of disadvantage” (p. 1). The authors note that both the process and outcomes of marginalization can vary significantly across contexts (Fluit et al., 2024). See definitions in Box 1-3.

SOURCE: Lerner et al., 2005b, Figure 1.

its original version communicates a general developmental theory that fits well with OST program theories of change. The thriving model emphasizes positive or negative spirals and the significance of individual↔context interactions. This understanding of development in context (Sameroff, 2010) implies that participation in OST programs can shape young people’s growth and development. The thriving model describes development as a series of “individual↔context relations” that, over time, may ultimately lead to positive outcomes in adulthood (i.e., contribution to self, family, community; Lerner et al., 2005b, pp. 25–26). Individual↔context relations happen across a young person’s life, including within OST programs. Subsequent versions of this model include the five or six “Cs,” which have been used extensively in OST practice and are discussed later in this chapter.

This model was later updated and elaborated, drawing on a longitudinal study (the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development) to the Lerner & Lerner model, shown in Figure 2-2.

Like the thriving model in Figure 2-1, the Lerner & Lerner model (e.g., see Lerner & Lerner, 2019; Lerner et al., 2015, 2021) stresses individual↔context

relations (also known as proximal processes) in a developmental systems framework. It describes positive development using the “five Cs” of positive youth development, described in the next section (see Box 2-1), and emphasizes ecological and individual assets, as well as risk. In both conceptualizations (Figures 2-1 and 2-2), the result of thriving personhood is contribution—to self, family, community, and civil society.

Many scholars and practitioners have used adolescent development research and theory to note the unique role that OST can play for adolescents. Stage–environment fit theory, originally developed to contrast the structures of junior high school with young people’s developmental needs, provides a clear example. Simply put, it is the idea that contexts are more effective when they match or “fit” with young people’s developmental stage (Eccles & Midgley, 1989; Eccles et al., 1993). For example, scholarship on adolescent development emphasizes the importance for fit in increasing independence, autonomy, and abstract and hypothetical thinking (Steinberg, 2014). OST programs can provide strong fit (e.g., youth in an advisory council making decisions about how to allocate funding).

Another youth developmental model is the framework presented in the report Foundations for Young Adult Success from the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research (Nagaoka et al., 2015; see Figure 2-3). This model provides a useful synthesis of research-supported concepts that seem to matter for productive development (e.g., self-regulation, knowledge, skills). The report does not, however, describe specifically the role of OST programs in young people’s lives.

SOURCE: Nagaoka et al., 2015.

Positive Youth Development

The theory most associated with OST programs is positive youth development, sometimes shortened to “youth development”; many refer to OST programs as “youth development programs.” Positive youth development is understood to be (1) a developmental process, (2) a set of principles for working with young people, and (3) programs or practices for children and youth (Hamilton, 1999; Lerner et al., 2011). The principles of positive youth development have been defined in various ways, including the five Cs model (Pittman et al., 2001)—competence, confidence, character, connection, and caring—and the potential for a sixth C: contribution to self, family, community, and civil society (Lerner, 2004).

Additionally, the Search Institute’s developmental assets approach, which identifies 20 internal and 20 external assets, is also closely associated with positive youth development (Search Institute, 2006). And the list of features in the 2002 National Academies report Community Programs to Promote Youth Development (National Research Council [NRC] & Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2002, see Table 4-1 in this report) was hugely influential in defining the principles of positive youth development.

Although positive youth development is expansive and includes multiple theories, a few key features help define this approach. First, it is strengths based, focusing on young people’s assets and resiliency. This is especially in contrast to the “storm and stress” model proposed by G. Stanley Hall (1904), still influential today.4 Second, it recognizes the impact of ecological supports and opportunities and the importance of relationships. Third, most positive youth development (PYD) models emphasize young people’s agency in their development and learning. These ideas are summarized by the official definition provided by the Interagency Working Group on Youth Programs, a set of more than 20 U.S. federal agencies related to youth development (Office of Population Affairs, n.d.):

PYD is an intentional, prosocial approach that engages youth within their communities, schools, organizations, peer groups, and families in a manner that is productive and constructive; recognizes, utilizes, and enhances young people’s strengths; and promotes positive outcomes for young people by providing opportunities, fostering positive relationships, and furnishing the support needed to build on their leadership strengths. (para. 2)

Laying Groundwork for Critical Approaches

Some scholars have argued that positive youth development was always aligned with critical approaches. For example, Lerner et al. (2021) argued,

___________________

4 See Chapter 1 for more detail on the “storm and stress” model.

“models emphasized that all young people could thrive when given equitable treatment and the fair allocation of the resources needed for healthy and positive development” (p. 1117). However, many scholars acknowledge that initial conceptualizations of positive youth development did not center the development of children and youth from marginalized backgrounds. Several later models make this conceptualization explicit within the positive youth development framework. For example, Coyne-Beasley et al. (2024) note that there are several important developmental tasks during adolescence, including exploring one’s identity, developing and applying abstract thinking, adjusting to a new physical sense of self, and fostering stable and productive peer relationships while striving for autonomy and independence from parents. The authors argue that, during this period, young people begin to adopt a personal value system and form their racial and ethnic, social, sexual, and moral identity within a society that may provide conflicting and nonaffirming messages. They point out that striving toward an affirmed sense of self and self-esteem is best accomplished within a nurturing psychosocial context that fosters positive youth development and promotes affirmation of identities (Coyne-Beasley et al., 2024).

Relatedly, intersectionality theory, as defined by Crenshaw (1989), recognizes the intractable overlap of social positions (e.g., race, gender) that cannot be otherwise understood separately, and furthermore that intersecting systems of power inform people’s social positioning and experiences. Crenshaw and her colleagues’ conceptualizations of intersectionality highlight the role of race, ethnicity, gender, orientation, and identities as objects of overlapping areas of marginalization, discrimination, and structural inequality (Coyne-Beasley et al., 2024; Crenshaw, 1989; Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995).5

Ginwright and Cammarota (2002) argued that the positive youth development approach, though successful in helping move away from a problem- and risk-focused model, is limited “by promoting supports and opportunities as the only factors necessary for positive and healthy development of youth and does not examine thoroughly the ways in which social and community forces limit and create opportunities for youth” (p. 84). They argue instead for a social justice youth development (SJYD) approach

___________________

5 Another important model that has been used in positive youth development (e.g., Swanson et al., 2002) is the phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST; Spencer, 2006; Spencer et al., 1997, 2015). As articulated by Spencer et al., PVEST combines ecological theory with a phenomenological approach, asserting the importance of individuals’ perception of experience (Spencer et al., 1997, 2015). Velez and Spencer (2018) use PVEST to interrogate “how structures and norms shape how youth think about themselves and their place in society” (p. 82) and how youth make meaning of contextual conditions and experiences of stereotypes and biases (Cunningham et al., 2023). PVEST is also discussed in the Ecological Theories section.

that acknowledges the systems and historical drivers of gaps in opportunity and access, such as racism, and integrates critical consciousness and social action into youth development (Ginwright & Cammarota, 2002). According to Lerner et al. (2021), social justice perspectives of youth development resonate with conceptual models that view young people as agentic and important actors in their respective contexts with critical social capital that helps them recognize and resist discriminatory portrayals of their identities and abilities (Ginwright & Cammarota, 2002; Lerner et al., 2021). As Baldridge (2020) notes, SJYD makes identity development central, includes critical analysis of power and systems, and considers young people as agents in promoting positive societal change (Ginwright & James, 2002).6 More recently, Ginwright (2018) has argued for a healing-centered approach that he described as building from positive youth development and trauma-informed care (see Box 2-1).

The SJYD approach has been significant in the youth organizing and civic engagement movement. For some youth, active civic engagement may be an adaptive means for coping with unfairness (Diemer & Rapa, 2016; Ginwright, 2006; Hope & Spencer, 2017). In a recent multimethods study of middle and late adolescents in seven community organizations (four in the United States, two in Ireland, and one in South Africa), many of which served low-income or working-class communities, researchers found that the context of youth organizing promoted the skills of critical thinking and analysis, social and emotional learning, and involvement in community leadership and action (Watts et al., 2011). Related research on community leadership and action, grounded in the work of Brazilian educator Paolo Freire (1973), has examined adolescents’ critical reflection, motivation, and action (Diemer et al., 2015; Watts et al., 2011). Youth with higher levels of critical reflection, motivation, and action are more likely to recognize unfairness and may feel a greater sense of agency or efficacy in responding to it (Diemer & Rapa, 2016; Shedd, 2015).

Two more recent variations of positive youth development are critical youth development and critical positive youth development, which

___________________

6 Several scholars define a social justice perspective of positive youth development as intentionally centering programs and spaces that foster critical consciousness, and sociopolitical development that recognizes historic inequities, empowers youth, and creates opportunities for youth participatory action research in the United States and around the globe (Lerner et al., 2021; Ozer et al., 2024; Smith et al., 2021; Watts et al., 2003, 2011). This work examines how positive youth development is linked to the development of positive racial/ethnic identities and how acknowledging racial barriers can use racial pride to develop caring, connected, competent citizens (Yu et al., 2021). These scholars note that developing an awareness of the sociopolitical context (a process Freire termed conscientization), is part of the pathway to youth participatory action research, in which youth analyze and develop actions to resist racism and unjust treatment (Lerner et al., 2020; Ozer et al., 2024; Smith et al., 2021; Watts et al., 2003, 2011).

BOX 2-1

Healing-Centered Engagement

Healing-centered engagement (HCE) seeks to improve organizational culture, transform individual practices, and build healthy outcomes for young people and the adults who serve them. HCE is a nonclinical, strengths-based approach that advances a holistic view of healing and recenters culture and identity as a central feature in personal well-being for young people, their families, and those who work with them. The HCE approach is operationalized through five “CARMA” principles:

- Culture: The values and norms that connect us to a shared identity.

- Agency: The individual and collective power to act, create, and change personal conditions and external systems.

- Relationships: The capacity to create, sustain, and grow healthy connections with others.

- Meaning: The profound discovery of who we are, why we are, and what purpose we were born to serve.

- Aspiration: The capacity to imagine, set, and accomplish goals for personal and collective livelihood and advancement.

HCE has been implemented in a variety of youth-serving organizations, including the San Francisco Unified School District, the Alameda County Office of Education, the San Francisco Department of Children and Families, and the City of Oakland’s Oakland Unite.

SOURCE: FlourishAgenda (n.d.).

are largely compatible with each other (Gonzalez et al., 2020; McGee, 2019). The former emerged from practice; as McGee (2019) articulates, it centers engaging young people in dialog around identity, power, privilege, and oppression (McGee, 2019). Gonzalez et al. (2020) presents a model in which critical reflection and political efficacy work alongside the five Cs of youth development (caring, competence, confidence, connection, character) to lead to engagement in critical action. Similarly, Zeller-Berkman (2010) argued that evaluation in the youth development field is overly focused on the outcomes of individual children and youth, and that the embrace of a critical approach would lead to more focus on community- and systems-level outcomes.

Emphasizing Youth Agency and Involvement

As children reach adolescence, agency and authentic engagement in practice and leadership become increasingly important for identity formation

(Arnold, 2017), meaning-making, and autonomy. Developmental research has consistently described increased autonomy during the adolescent years (Steinberg, 2014). Adolescence is often described as a period of differentiation from caregivers, when an adolescent’s feelings, beliefs, and decisions become their own, although they may still be highly influenced by caregivers (National Academies, 2019b).

Alongside these developmental changes, scholars and OST practitioners have described various approaches to supporting youth’s autonomy, including their voice and agency, and youth-driven and youth–adult partnerships. The youth–adult partnership approach centers youth voice, decision-making, and interaction with adults (Zeldin et al., 2013). This approach, which been implemented across the youth development field, as well as in several other contexts, involves allowing and supporting youth voice and decision-making, especially in areas where adults typically make decisions (Akiva & Petrokubi, 2016)—for example, having youth share feedback, lead or help lead meetings, and even engage in strategies for recruiting new youth and staff (Wu et al., 2022).

Some scholarship has investigated the challenge of implementing youth–adult partnerships in youth programs. For example, Camino (2005) described the “pitfalls” of adhering to simplified notions the approach of the youth-adult partnership approach: youth must make every decision, adults need to just “get out of the way,” and adult development is considered inadequately. Addressing these pitfalls requires skill and scaffolding. For example, the Youth-Driven Spaces Project offers cohort-based, multimonth workshops to help existing youth programs increase their youth–adult partnerships and increase youth voice and decision-making (e.g., having youth serve on an organization’s board of directors; see The Neutral Zone, n.d.).

ECOLOGICAL THEORIES OF HUMAN DEVELOPMENT: UNDERSTANDING WHAT MAY INFLUENCE A YOUNG PERSON IN OST SETTINGS

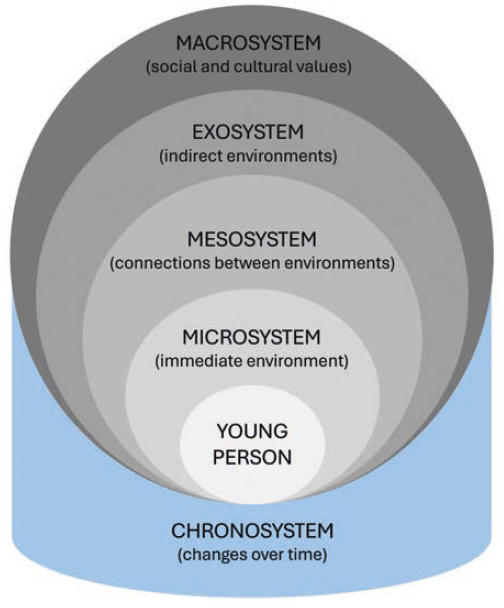

The second set of theories associated with OST programs is ecological theories of human development. Most prominent among these is bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), originally called ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Bioecological theory is often used in discussions of OST systems and settings, as it provides a way to consider what factors might be influential in program settings and how those settings may interact with other important contexts in a young person’s life, such as family and school (Vandell et al., 2015). The bioecological model puts young people at the center of concentric circles and identifies a set of systems, from proximal (close to and able to be affected by children and

youth) to distal (further from them and less accessible). The microsystem is closest, including settings of school and OST programs. Next is the mesosystem, which is defined as the interactions between microsystems. In the youth development field, OST intermediaries work intentionally in the mesosystem. Farther out are exosystems—which, like the mesosystem, involve relationships between systems but do not involve the young person directly. Farthest from the center are macrosystems—society-level systems such as culture, law, and government. Finally, the chronosystem depicts time, both as related to important milestones in a young person’s life (e.g., starting school) and the historical period in which development occurs (see Figure 2-4).

The microsystems most relevant to OST include youth development programs, schools, friends, and families. The concept of microsystems, from bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), has often been applied to youth programs. That is, a youth development program can serve

SOURCE: Committee generated based on Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006; adapted from Budzyna & Buckley, 2023.

as a microsystem, defined as “a pattern of activities, social roles, and interpersonal relations experienced by the developing person” (Bronfenbrenner, 1994, p. 1645). A youth development program also serves as a behavior setting—a context in which aspects such as physical space, materials, and staff interaction patterns evoke standing behavior patterns (Barker, 1968; Schoggen, 1989). For example, the physical features of a coffee shop evoke particular behaviors from customers (where to stand, where to sit, how to order, etc.). Based on this theory, child and youth behaviors (and outcomes) in OST programs depend on the features of these programs.

It is important to note that although macrosystems are distal to children and youth in the sense that a young person has little power to affect them, those systems affect young people’s experience directly.

The bioecological model of human development evolved over time. The final model includes Process-Person-Context-Time, a set of four concepts and propositions. Process indicates proximal processes, or an individuals’ interaction with people, objects, or symbols; these are considered the “engines of development” (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006, p. 822). Bronfenbrenner and Morris (2006) suggest that

human development takes place through processes of progressively more complex reciprocal interaction between an active, evolving biopsychological human organism and the persons, objects, and symbols in its immediate external environment. To be effective, the interaction must occur on a fairly regular basis over extended periods of time. (p. 797)

The model describes person as the role of personal characteristics in social interactions, context as the five systems in the bioecological modes, and time is included at multiple levels (micro, meso, and macro) to indicate development over time.

Versions of bioecological theory are common across the education and youth development fields.7 These versions can be powerful as they make clear how multiple factors influence learning in development—offering advocates of OST programs a framework for describing their importance.

___________________

7 For example, a 2015 National Academies report discusses the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) learning ecosystem model. STEM learning ecosystem scholarship roots itself in ecological perspectives (e.g., Bronfenbrenner, 1979), and some draw comparisons to biological ecosystems (Bevan, 2016; see NRC, 2015). Scholars note that the ecological perspective—that STEM learning occurs over time across formal, informal, and everyday settings—aligns with research on how people learn (Bevan, 2016; Bevan et al., 2018). In practice, this approach includes initiatives to design and develop existing ecosystems, strengthen cross-setting connections and partnerships, illuminate pathways for learning, and increase and broaden learning experiences for young people (Dahn et al., 2023; Vance et al., 2016). For more information on STEM learning ecosystems, see www.stemecosystems.org

The bioecological model continues to be popular 50 years since its conception, likely because it helps organize influences on development conceptually in ways that support action (e.g., focusing interventions on the mesosystem to affect the microsystem).

PVEST integrates a phenomenological approach with the systems focus of the bioecological model (Cunningham et al., 2023; Spencer et al., 1997, 2015). Spencer et al. (2015) argue that a major contribution is the notion that phenomenological experience—an individuals’ perception of experience—shapes development, particularly identity development. PVEST emphasizes self-appraisal as key to coping and identity formation. In its final form (Spencer et al., 2015), PVEST is a cyclic model with five components, all associated with bidirectional processes: net vulnerability (risks and protective factors), net stress (overall experience of situations that challenge identity and well-being), reactive coping processes (adaptive and maladaptive), emergent identities, and stage-specific coping processes. Emergent identities is defined as “how individuals view themselves within and between their various experiences in different contexts” (Spencer et al., 2015, p. 758).

In their description of an integrative model, García Coll et al. (1996) argue that ecological theories, such as the bioecological theory, require “both expansion and greater specification” (p. 1893). Using research with Black and Puerto Rican young people as examples, they presented a model for development that includes social position (race and ethnicity, social class, gender), racism (prejudice, discrimination, oppression), segregation (residential, economic, social and psychological), adaptive culture (traditions, cultural legacies, economic and political histories, migration and acculturation) as factors that affect development (García Coll et al., 1996, p. 1896). As an example, “children of color who grow up in a poor, all Dominican neighborhood [. . .] may not have access to adequate resources such as [. . .] after-school programs” (García Coll & Szalacha, 2004, p. 86).

In a more recent developmental theory, the cultural microsystem model, Vélez-Agosto et al. (2017) argue that in Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory, culture is ill defined and considered part of the macrosystem, the most distal ring. They argue that this is problematic because it suggests culture is separate from microsystems/proximal experience—something that is “‘out there’ in the distal environment” (Vélez-Agosto et al., 2017, p. 901). Instead, they contend, all learning and development occur within and through culture: “Culture is both the process and the content of daily activity and is thus inseparable from all contexts where developmental processes and outcomes take place, especially in the microsystems” (Vélez-Agosto et al., 2017, p. 903). Based on Vygotskian and neo-Vygotskian perspectives, the cultural microsystem model emphasizes how culture acts in both proximal and distal ways in many settings (e.g., family, childcare, school).

The bioecological model was instrumental in moving developmental theory away from views of child development that gave inadequate

attention to context. However, the model is designed for understanding individual development in context and is not especially good at helping move larger entities, such as cities, to an ecological approach for learning (Akiva et al., 2022). For example, Hecht and Crowley (2019) argue that

this persistent focus on youth as the center of the learning ecosystem undermines the potency of the ecosystem framework [and] perpetuates the idea that learning happens at the individual level and that systemic inequity can be addressed by supporting opportunities for individuals. (p. 10)

THEORETICAL MODELS SPECIFIC TO OST SETTINGS

Models specific to OST settings and programs present theoretical frameworks for understanding how OST programs work and what makes them more or less successful, as well as the role of OST programs in society or in learning ecosystems. See, for example, the features presented in the National Academies consensus report Community Programs to Promote Youth Development (NRC & IOM, 2002). The report theorizes that, when present, these features make an OST program effective and beneficial to participants:

- physical and psychological safety;

- appropriate structure;

- supportive relationships;

- opportunities to belong;

- positive social norms;

- support for efficacy and mattering;

- opportunities for skill-building; and

- integration of family, school, and community.

Simpkins et al. (2017) extend this theory by elaborating on how these features can play out in culturally responsive ways. Chapter 6 expands on this discussion to capture additional program features that help create positive developmental settings for children and youth.

The developmental ecological model, presented by Durlak et al. (2010) in a special issue of the American Journal of Community Psychology, provides a basic template that is compatible with many subsequent models (see Figure 2-5).

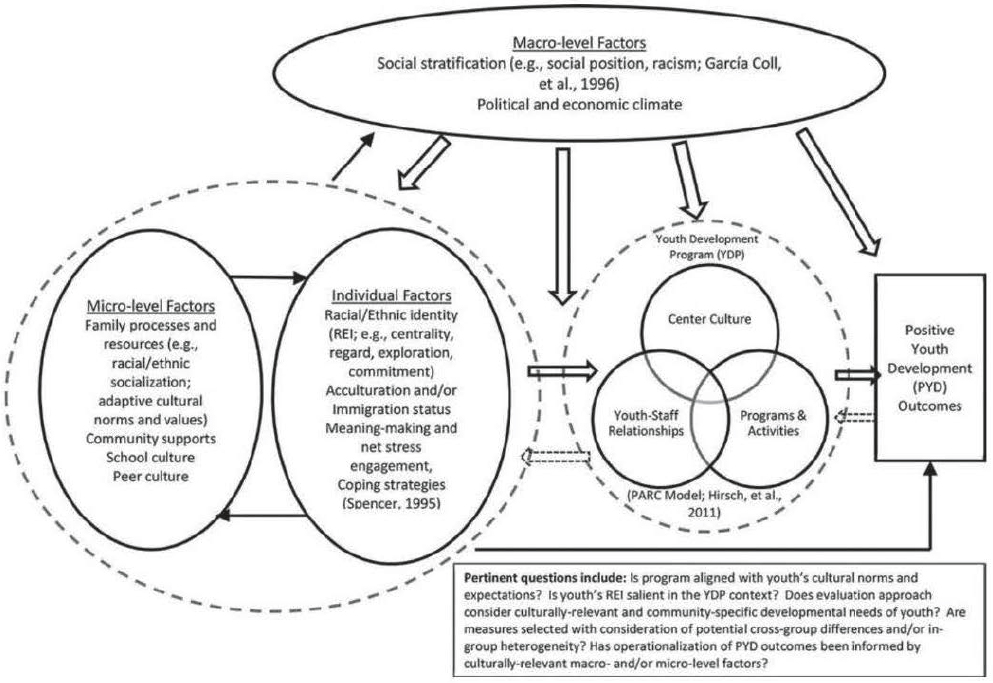

In Afterschool Centers and Youth Development, Hirsch et al. (2011) describe the PARC (programs, activities, relationships, and culture) model (see Figure 2-6). This model, built from profiles of three afterschool centers (233 site visits), suggests that the effectiveness of programs is determined by the center’s culture, its youth–adult relationships, and the nature of its programs and activities.

In an extension of the PARC model, Williams and Deutsch (2016) created the chart shown in Figure 2-7 to address how race, ethnicity, culture,

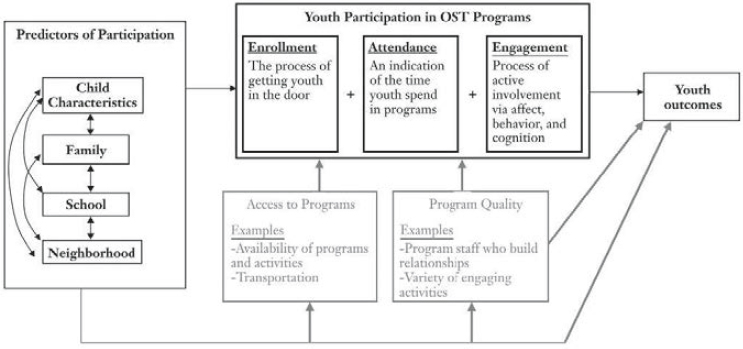

NOTE: OST = out-of-school-time.

SOURCE: Weiss et al., 2005.

and other factors shape the basic PARC features. Note that neither of these models specifies the effective features of youth programs, except to say that youth–staff relationships and program culture matter.

The Harvard Family Research Project conceptual model of participation (Figure 2-8) highlights the multiple dimensions of participation: enrollment, attendance, and engagement (Weiss et al., 2005). In other ways, it is similar to the developmental ecological model of Durlak et al. (2010).

Routine activity theory emerged from criminology and was first proposed by Cohen and Felson (2015; see Figure 2-9). The theory posits that

SOURCE: Abt, 2016.

the likelihood of an individual to commit a crime is strongly associated with key contextual factors around them—i.e., situational motivation. For example, reducing opportunities for crime reduces crime. Osgood et al. (2005) apply this theory to OST settings. Part of their rationale is that the largest percentage of juvenile arrests for aggravated assault occur between 3 p.m. and 6 p.m. (as of 1999). They provided detailed descriptions of structured versus unstructured time and argued that participation in structured activities (i.e., OST programs, with adult supervision, which restrict how time is spent) reduces the opportunity for unsupervised time that can lead to engagement in risk-taking behaviors: “The less structured an activity, the more likely a person is to encounter opportunities for problem behavior in the simple sense that he or she is not occupied doing something else” (Osgood et al., 2005, p. 51; See Box 4-2 for more discussion of unsupervised time). Routine activity theory is largely a call to reduce unstructured time, but it also provides some theoretical justification for structured OST time.

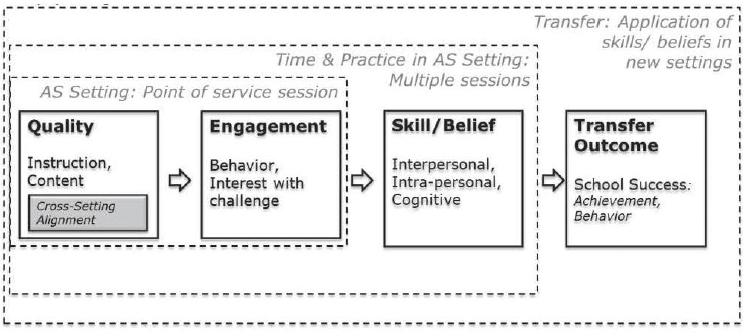

The QuEST model by Smith and McGovern (2014) targets four items: quality, engagement, skill, and transfer (see Figure 2-10). This model suggests that OST programs lead to social and emotional skill development in participants, especially over time and in multiple sessions; this growth depends on a basis of quality and youth engagement. This is related to the active ingredient hypothesis, which suggests that all social programs’ effectiveness depends on the interactions and relationships that occur in those programs—in other words, developmental relationships are the active ingredient (Li & Julian, 2012). Ultimately, this can lead to success in other contexts—most predominantly school.

NOTE: AS = afterschool.

SOURCE: Smith & McGovern, 2014, p. 2.

The National Science Foundation’s Learning in Informal and Formal Environments Center offers the where and when learning happens model, which provides some theoretical assumptions about OST and puts OST on a spectrum from core academic classes at the top and community learning settings at the bottom (see Figure 2-11).

CONCLUSION

Developmental and ecological theories are commonly used to guide researchers and practitioners in the youth development field in their consideration of learning and human development within OST settings—including how time spent in OST settings can shape young people’s growth, the factors within these settings that might be influential, and how these settings interact with other parts of their lives. These theories have then been applied to establish OST program tools and trainings. The theory of positive youth development is most associated with OST programs, offering approaches that recognize and emphasize the strengths of young people, their circumstances and relationships, and their individual agency. In recent decades, scholars have increasingly considered the role of social position, culture, power, resources, and discrimination to understand the unique experiences of children and youth. These conceptualizations examine the ways in which social and community forces influence opportunities and outcomes.

Although these theoretical discussions are focused on learning and development broadly, other theoretical models are specific to OST settings; these focus on understanding how OST programs work, what makes them more or less successful, and their role in society. These models have connected program effectiveness to the nature of programs and activities, level of participant attendance and engagement, program quality and culture, and relationships and interactions with peers and adults.

In the chapters that follow, the report seeks to put the theories reviewed here into action describing what is known about OST programs and workforce; how programs and the workforce influence program quality and experiences; the interaction between quality and participation; and how those interactions lead to skill-building and outcomes (e.g., improved social and emotional learning for children and youth).

REFERENCES

Abt, T. P. (2016). Towards a framework for preventing community violence among youth. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(Suppl 1), 266–285.

Akiva, T., Hecht, M., & Blyth, D. A. (2022). Using a learning and development ecosystem framework to advance the youth fields. In T. Akiva & K. H. Robinson (Eds.), It takes an ecosystem: Understanding the people, places, and possibilities of learning and development across settings (pp. 13–36). Information Age Publishing.

Akiva, T., & Petrokubi, J. (2016). Growing with youth: A lifewide and lifelong perspective on youth-adult partnership in youth programs. Children and Youth Services Review, 69, 248–258.

Arnold, K. A. (2017). Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 381.

Baldridge, B. J. (2020). The youthwork paradox: A case for studying the complexity of community-based youth work in education research. Educational Researcher, 49(8), 618–625.

Barker, R. G. (1968). Ecological psychology. Stanford University Press.

Berry, T., & LaVelle, K. B. (2013). Comparing socioemotional outcomes for early adolescents who join after school for internal or external reasons. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 33(1), 77–103.

Bevan, B. (2016). STEM learning ecologies: Relevant, responsive, and connected. Connected Science Learning, 1(1). https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning/connected-science-learning-march-2016/stem-learning-ecologiedeis

Bevan, B., Garibay, C., & Menezes, S. (2018). What is a STEM learning ecosystem? Center for Advancement of Informal Science Education. https://informalscience.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/BP-7-STEM-Learning-Ecosystem.pdf

Bornstein, M. H. (2017). The specificity principle in acculturation science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(1), 3–45.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

———. (1994). Ecological models of human development. International Encyclopedia of Education, 3(2), 37–43.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). Wiley.

Budzyna, D., & Buckley, D. (2023). The whole child: Development in the early years. Rotel Project. https://rotel.pressbooks.pub/whole-child/chapter/ecological-theory-2

Camino, L. (2005). Pitfalls and promising practices of youth–adult partnerships: An evaluator’s reflections. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(1), 75–85.

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (2015). Routine activity theory: A routine activity approach. In Criminology Theory (pp. 313–321). Routledge.

Coyne-Beasley, T., Miller, E., & Svetaz, M. V. (2024). Racism, identity-based discrimination, and intersectionality in adolescence. Academic Pediatrics, 24(7), S152–S160.

Cox, D. R. (1984). Interaction. International Statistical Review, 52(1), 1–24.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167.

Cunningham, M., Swanson, D. P., Youngblood, J., II, Seaton, E. K., Francois, S., & Ashford, C. (2023). Spencer’s phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST): Charting its origin and impact. American Psychologist, 78(4), 524.

Dahn, M., Peppler, K., & Ito, M. (2023). Making connections to and from out-of-school experiences. Review of Research in Education, 47(1), 443–473. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X231211271

Dawes, N. P., & Larson, R. (2011). How youth get engaged: Grounded-theory research on motivational development in organized youth programs. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 259.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

———. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Diemer, M. A., McWhirter, E. H., Ozer, E. J., & Rapa, L. J. (2015). Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of critical consciousness. The Urban Review, 47, 809–823.

Diemer, M. A., & Rapa, L. J. (2016). Unraveling the complexity of critical consciousness, political efficacy, and political action among marginalized adolescents. Child Development, 87(1), 221–238.

Durlak, J. A., Mahoney, J. L., Bohnert, A. M., & Parente, M. E. (2010). Developing and improving after-school programs to enhance youth’s personal growth and adjustment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45, 285–293.

Eccles, J. S., & Midgley, C. (1989). Stage/environment fit: Developmentally appropriate classrooms for early adolescence. In Ames, R. E., & Ames, C. (Eds.), Research on motivation in education (Vol. 3, pp. 139–186). Academic Press.

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & MacIver, D. (1993). The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48(2), 90–101.

Faust, L., & Kuperminc, G. P. (2020). Psychological needs fulfillment and engagement in afterschool: “I pay attention because I am really enjoying this.” Journal of Adolescent Research, 35(2), 201–224.

FlourishAgenda. (n.d.). Our process. https://flourishagenda.com/our-process

Fluit, S., Cortés-García, L., & von Soest, T. (2024). Social marginalization: A scoping review of 50 years of research. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–9.

Freire, P. (1973). Education for a critical consciousness. Seabury.

García Coll, C., Lamberty, G., Jenkins, R., Mcadoo, H. P., Crnic, K., Wasik, B. H., & García, H. V. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914.

García Coll, C., & Szalacha, L. A. (2004). The multiple contexts of middle childhood. The Future of Children, 14, 81–97.

Ginwright, S. (2006). Racial justice through resistance: Important dimensions of youth development for African Americans. National Civic Review, 95, 41.

———. (2018). The future of healing: Shifting from trauma informed care to healing centered engagement. Medium. https://ginwright.medium.com/the-future-of-healing-shifting-from-trauma-informed-care-to-healing-centered-engagement-634f557ce69c

Ginwright, S., & Cammarota, J. (2002). New terrain in youth development: The promise of a social justice approach. Social Justice, 29(4), 82–95.

Ginwright, S., & James, T. (2002). From assets to agents of change: Social justice, organizing, and youth development. In B. Kirshner, J. L. O’Donoghue, & M. McLaughlin (Eds.), Youth participation: Improving institutions and communities (pp. 27–46). Jossey-Bass.

Godbey, G., Crawford, D. W., & Shen, X. S. (2010). Assessing hierarchical leisure constraints theory after two decades. Journal of Leisure Research, 42(1), 111–134.

Gonzalez, M., Kokozos, M., Byrd, C. M., & McKee, K. E. (2020). Critical positive youth development: A framework for centering critical consciousness. Journal of Youth Development, 15(6), 24–43.

Hall, G. S. (1904). Adolescence: Its psychology and its relation to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education (Vols. I & II). Prentice-Hall.

Hamaker, E. L., Asparouhov, T., Brose, A., Schmiedek, F., & Muthén, B. (2018). At the frontiers of modeling intensive longitudinal data: Dynamic structural equation models for the affective measurements from the COGITO study. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 53(6), 820–841.

Hamilton, S. F. (1999). A three-part definition of youth development [Unpublished manuscript]. Cornell University College of Human Ecology.

Hecht, M., & Crowley, K. (2019). Unpacking the learning ecosystems framework: Lessons from the adaptive management of biological ecosystems. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 29(2), 1–21.

Hirsch, B. J., Deutsch, N. L., & DuBois, D. L. (2011). After-school centers and youth development: Case studies of success and failure. Cambridge University Press.

Hope, E. C., & Spencer, M. B. (2017). Civic engagement as an adaptive coping response to conditions of inequality: An application of phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST). In Handbook on positive development of minority children and youth (pp. 421–435). Springer.

Jones, D., Feigenbaum, P., & Jones, D. F. (2021). Motivation (constructs) made simpler: Adapting self-determination theory for community-based youth development programs. Journal of Youth Development, 16(1), 7–28.

Ladson-Billings G., & Tate, W. F. (1995). Toward a critical race theory of education. Teachers College Record, 97(1), 47–68.

Larson, R., & Hansen, D. (2005). The development of strategic thinking: Learning to impact human systems in a youth activism program. Human Development, 48(6), 327–349.

Lerner, R. (2021). Individuals as producers of their own development: The dynamics of person-context coactions. Taylor & Francis.

Lerner, R. M. (2004). Liberty: Thriving and civic engagement among America’s youth. SAGE Publications.

Lerner, R. M., Almerigi, J. B., Theokas, C., & Lerner, J. V. (2005a). Positive youth development: A view of the issues. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 10–16.

Lerner, R. M., & Bornstein, M. H. (2021). Contributions of the specificity principle to theory, research, and application in the study of human development: A view of the issues. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 75, 1–5.

Lerner, R. M., & Lerner, J. V. (2019). The development of a person: A relational developmental systems perspective. In D. P. McAdams, R. L. Shiner, & J. L. Tackett (Eds.), Handbook of personality development (pp. 59–75). Guilford Press.

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Almerigi, J. B., Theokas, C., Phelps, E., Gestsdottir, S., Naudeau, S., Jelicic, H., Alberts, A., Ma, L., Smith, L. M., Bobek, D. L., Richman-Raphael, D., Simpson, I., Christiansen, E. D., & von Eye, A. (2005b). Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth-grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 17–71.

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Bowers, E., & Geldhof, G. J. (2015). Positive youth development and relational developmental systems. In W. F. Overton & P. C. Molenaar (Eds.), Theory and method: Volume 1 of the handbook of child psychology and developmental science (7th ed., pp. 607–651). Wiley.

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., & Buckingham, M. H. (2023). The development of the developmental science of adolescence: Then, now, next—and necessary. In L. J. Crockett, G. Carlo, & J. E. Schulenberg (Eds.), APA handbook of adolescent and young adult development (pp. 723–741). American Psychological Association.

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Lewin-Bizan, S., Bowers, E. P., Boyd, M. J., Mueller, M. K., Schmid, K. L., & Napolitano, C. M. (2011). Positive youth development: Processes, programs, and problematics. Journal of Youth Development, 6(3), 38–62.

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Murry, V. M., Smith, E. P., Bowers, E. P., Geldhof, G. J., & Buckingham, M. H. (2021). Positive youth development in 2020: Theory, research, programs, and the promotion of social justice. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(4), 1114–1134.

Li, J., & Julian, M. M. (2012). Developmental relationships as the active ingredient: A unifying working hypothesis of “what works” across intervention settings. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(2), 157.

Mahoney, J. L., Parente, M. E., & Zigler, E. F. (2009). Afterschool programs in America: Origins, growth, popularity, and politics. Journal of Youth Development, 4(3).

McGee, M. (2019). Critical youth development: Living and learning at the intersection of life. In S. Hill & F. Vance (Eds.), Changemakers! Practitioners advance equity and access in out-of-school time programs. Sagamore-Venture.

Molenaar, P. C. (2004). A manifesto on psychology as idiographic science: Bringing the person back into scientific psychology, this time forever. Measurement, 2(4), 201–218.

Nagaoka, J., Farrington, C. A., Ehrlich, S. B., Heath, R. D., Johnson, D. W., Dickson, S., Turner, A. C., Mayo, A., & Hayes, K. (2015). Foundations for young adult success: A developmental framework. University of Chicago Consortium on School Research.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies). (2019a). Shaping summertime experiences: Opportunities to promote healthy development and well-being for children and youth. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25546

———. (2019b). The promise of adolescence: Realizing opportunity for all youth. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25388

———. (2019c). Vibrant and healthy kids: Aligning science, practice, and policy to advance health equity. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25466

National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development. (2019). From a nation at risk to a nation at hope. Recommendations from the National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development. The Aspen Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/media/3962/download?inline&file=Aspen_SEAD_Nation_at_Hope.pdf

National Research Council. (2015). Identifying and supporting productive STEM programs in out-of-school settings. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21740

National Research Council & Institute of Medicine. (2002). Community programs to promote youth development. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10022

The Neutral Zone. (n.d.). Youth driven spaces approach. https://www.neutral-zone.org/yds-approach

Office of Population Affairs. (n.d.). Positive youth development. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://opa.hhs.gov/adolescent-health/positive-youth-development

Osgood, D. W., Anderson, A. L., & Shaffer, J. N. (2005). Unstructured leisure in the afterschool hours. In Organized activities as contexts of development (pp. 57–76). Psychology Press.

Ozer, E. J., Abraczinskas, M., Suleiman, A. B., Kennedy, H., & Nash, A. (2024). Youth-led participatory action research and developmental science: Intersections and innovations. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 6(1), 401–423.

Pittman, K., Irby, M., & Ferber, T. (2001). Unfinished business: Further reflections on a decade of promoting youth development. In P. L. Benson & K. J. Pittman (Eds.), Trends in youth development: Visions, realities and challenges (Outreach Scholarship Series, Vol. 6). Springer.

Ram, N., Rabbitt, P., Stollery, B., & Nesselroade, J. R. (2005). Cognitive performance inconsistency: Intraindividual change and variability. Psychology and Aging, 20(4), 623.

Rose, T. (2016). The end of average: How we succeed in a world that values sameness. Harper Collins.

Sameroff, A. (2010). A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development, 81(1), 6–22.

Schoggen, P. (1989). Behavior settings: A revision and extension of Roger G. Barker’s “ecological psychology.” Stanford University Press.

Search Institute. (2006). Developmental assets. https://searchinstitute.org/resources-hub/developmental-assets-framework

Shedd, C. (2015). Unequal city: Race, schools, and perceptions of injustice. Russell Sage Foundation.

Simpkins, S. D., Riggs, N. R., Ngo, B., Vest Ettekal, A., & Okamoto, D. (2017). Designing culturally responsive organized after-school activities. Journal of Adolescent Research, 32(1), 11–36.

Sjogren, A. L., Robinson, K. A., & Koenka, A. C. (2023). Profiles of afterschool motivations: A situated expectancy-value approach. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 74, 102197.

Smith, C., & McGovern, G. (2014). The QuEST model: Out-of-school time contexts and individual-level change. Forum for Youth Investment. https://forumfyi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Brief-QuEST-Model.pdf

Smith, E. P., Yunes, M. A. M., & Fradkin, C. (2021). From prevention and intervention research to promotion of positive youth development: Implications for global research, policy and practice with ethnically diverse youth. In R. Dimitrova & N. Wiium (Eds.), Handbook of positive youth development: Advancing research, policy, and practice in global contexts (pp. 549–566). Springer.

Speelman, C. P., & McGann, M. (2013). How mean is the mean? Frontiers in Psychology, 4(451), 1–12.

Spencer, M. B. (2006). Phenomenology and ecological systems theory: Development of diverse groups. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 829–893). John Wiley & Sons.

Spencer, M. B., Dupree, D., & Hartmann, T. (1997). A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST): A self-organization perspective in context. Development and Psychopathology, 9(4), 817–833.

Spencer, M. B., Swanson, D. P., & Harpalani, V. (2015). Development of the self. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (Vol. 3, pp. 1–44). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy318

Steinberg, L. (2014). Age of opportunity: Lessons from the new science of adolescence. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Swanson, D. P., Spencer, M. B., Dell’Angelo, T., Harpalani, V., & Spencer, T. R. (2002). Identity processes and the positive youth development of African Americans: An explanatory framework. New Directions for Youth Development, 2002(95), 73–100.

Vance, D. F., Nilsen, D. K., Garza, D. V., Keicher, A., & Handy, D. (2016). Design for success: Developing a STEM ecosystem. University of San Diego. https://stemecosystems.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/USD-Critical-Factors-Final_121916.pdf

Vandell, D. L., Larson, R. W., Mahoney, J., & Watts, T. W. (2015). Children’s organized activities. In R. M. Lerner, W. Overton, & P. C. Molenaar (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (Vol. 4., 7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Velez, G., & Spencer, M. B. (2018). Phenomenology and intersectionality: Using PVEST as a frame for adolescent identity formation amid intersecting ecological systems of inequality. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2018(161), 75–90.

Vélez-Agosto, N. M., Soto-Crespo, J. G., Vizcarrondo-Oppenheimer, M., Vega-Molina, S., & García Coll, C. (2017). Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory revision: Moving culture from the macro into the micro. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 900–910.

Watts, R. J., Diemer, M. A., & Voight, A. M. (2011). Critical consciousness: Current status and future directions. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2011(134), 43–57.

Watts, R. J., Williams, N. C., & Jagers, R. J. (2003). Sociopolitical development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1–2), 185–194.

Weiss, H. B., Little, P. M. D., & Bouffard, S. M. (2005). More than just being there: Balancing the participation question. New Directions for Youth Development, 105, 15–31.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81.

Williams, J. L., & Deutsch, N. L. (2016). Beyond between-group differences: Considering race, ethnicity, and culture in research on positive youth development programs. Applied Developmental Science, 20(3), 203–213.

Wu, J. H. C., Shereda, A., Stacy, S. T., Weiss, J. K., & Heintschel, M. (2022). Maximizing youth leadership in out-of-school time programs: Six best practices from youth driven spaces. Journal of Youth Development, 17(3), 5.

Yu, D., Smith, E. P., & Oshri, A. (2021). Exploring racial–ethnic pride and perceived barriers in positive youth development: A latent profile analysis. Applied Developmental Science, 25(4), 332–350.

Zeldin, S., Christens, B. D., & Powers, J. L. (2013). The psychology and practice of youth-adult partnership: Bridging generations for youth development and community change. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51, 385–397.

Zeller-Berkman, S. (2010). Critical development? Using a critical theory lens to examine the current role of evaluation in the youth-development field. New Directions for Evaluation, 127, 35–44.