Preventing and Treating Dementia: Research Priorities to Accelerate Progress (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

Dementia exacts a weighty emotional and financial toll on individuals, families, and communities. As with any disease, the experiences of people living with dementia vary, and many find ways to adapt to cognitive changes and enjoy meaningful lives for many years. Over the long run, however, the effects of dementia can be devastating, with advanced stages often robbing people of their sense of self, their memories and independence, their emotional and financial well-being, and ultimately, their lives. Moreover, the societal impacts, including the effects on families and communities and the enormous health and long-term care costs, are likely to grow with an aging population in the United States and globally. The development of effective strategies for preventing and treating Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (AD/ADRD), a collection of neurodegenerative diseases that may ultimately lead to clinical dementia, is thus considered one of the most pressing biomedical research needs at present. There remains no cure, and recently approved therapies for slowing Alzheimer’s disease (AD), including lecanemab and donanemab, offer only modest clinical benefit to select AD patients; no approved treatments are available for people living with other forms of dementia beyond those for managing symptoms. A multitude of studies on the numerous nonpharmacologic strategies under investigation for preventing AD/ADRD have failed to provide definitive evidence on which strategies are effective and for whom.

And yet, the last couple of decades have witnessed encouraging and sometimes transformational scientific advances that are providing reason for optimism. Research investments by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other funders have led to improved understanding of the molecular

and cellular biology underlying AD/ADRD, including genetic contributions to risk and resilience, as well as the discovery of biomarkers that enable early identification of changes in brain health that may lead to AD/ADRD. In addition to creating opportunities for earlier intervention, biomarker discoveries have led to the identification of a new form of dementia (limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy) and the awareness that the majority of dementia cases feature a mix of pathologies. With the increased understanding of AD/ADRD has come a substantial expansion of the therapeutic pipeline (Cummings et al., 2024).

These past successes have built momentum and a foundation for accelerating the pace of discovery and catalyzing breakthroughs needed to develop effective prevention and treatment strategies for AD/ADRD. This report identifies research priorities focused on addressing current knowledge gaps that represent key bottlenecks impeding progress toward that goal. While the report is focused on opportunities to advance the science, the ultimate objective is to ensure that research investments translate to societal benefit by improving the lives of those already living with cognitive and other forms of impairment from AD/ADRD and preventing many more from developing these conditions.

STUDY ORIGIN AND STATEMENT OF TASK

Since passing the National Alzheimer’s Project Act in 2011,1 the U.S. Congress has made unprecedented investments in AD/ADRD research through targeted annual appropriations. In its Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023,2 Congress directed the National Institute on Aging (NIA), in collaboration with the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), to commission an independent National Academies study to identify promising areas of research and generate recommendations on research priorities to advance the prevention and treatment of AD/ADRD. The committee’s full Statement of Task is presented in Box 1-1.

STUDY SCOPE AND KEY TERMINOLOGY

The research and practice landscape related to brain health and dementia is exceptionally broad and multifaceted. While each element of the landscape is critically important, an examination and analysis of

___________________

1 Public Law 111-375.

2 The congressional language requesting this consensus study can be found in Division H of the Joint Explanatory Statement that accompanied H.R. 2617, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 (Public Law 117-328) on PDF page 496 here: https://www.congress.gov/117/cprt/HPRT50348/CPRT-117HPRT50348.pdf (accessed October 24, 2023).

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will conduct a study and recommend research priorities to advance the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (AD/ADRD). In conducting its study, the committee will:

- Examine and assess the current state of biomedical research aimed at preventing and effectively treating AD/ADRD, along the research and development pipeline from basic to translational to clinical research.

- Assess the evidence on nonpharmacological interventions (e.g., lifestyle, cognitive training) aimed at preventing and treating AD/ADRD.

- Identify key barriers to advancing AD/ADRD prevention and treatment (e.g., infrastructure challenges that impede large-scale precision medicine approaches, inadequate functional measures and biomarkers for assessing response to treatment, lack of diversity in biobanks and clinical trials), as well as opportunities to address these key barriers and catalyze advances across the field.

- Review and synthesize the most promising areas of research into preventing and treating AD/ADRD.

Building on its review of past AD/ADRD strategic planning and related activities, existing literature and analyses, and other expert and public input, the committee will develop a report with its findings, conclusions, and recommendations on research priorities for preventing and treating ADRD, including identifying specific near- and medium-term scientific questions (i.e., in a 3- to 10-year period) that may be addressed through National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding. The report will also include strategies for addressing major barriers to progress on these scientific questions.

The committee’s study will include dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease as well as related conditions such as frontotemporal disorders, Lewy body dementia, vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia, and multiple etiology dementias; dementias with a clear etiology (e.g., incident stroke, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS], traumatic brain injury) are outside the scope of this study. Dementia care and caregiving research, including care coordination, is outside the scope of this study.

the entire field is not feasible given the time and resources available to the committee. The Statement of Task limits this study to the area of AD/ADRD research and specifically research focused on prevention and treatment. During its first meeting on October 2, 2023, the committee had the opportunity to clarify remaining questions regarding the scope of the study with representatives from NIH. Specific points of clarification, which are described below, included the types of dementia and the types of AD/ADRD research that were within the study scope.

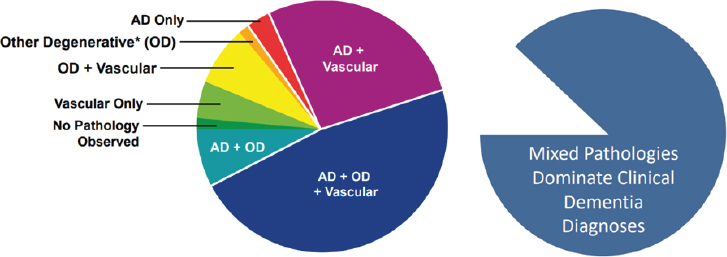

The Statement of Task specifies that the study’s scope includes Alzheimer’s disease and a number of other specific conditions that can ultimately cause clinical dementia. While Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a major contributor to clinical dementia, other common causes that fall within the study scope include frontotemporal dementia (FTD), Lewy body dementia (LBD), and vascular dementia. Excluded from the scope are nonneurodegenerative causes of clinical dementia—such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and traumatic brain injury—for which prevention and treatment strategies would follow from the known causes. Also excluded from the scope is clinical dementia arising acutely following incident stroke. Of note, vascular dementia developing in the years subsequent to a stroke was not excluded. Multiple etiology dementia, which is characterized by the identification of mixed pathologies in the brain of an individual experiencing clinical dementia symptoms, is also within the study scope (see descriptions of these disorders in Box 1-2). It should be noted, however, that the high prevalence of multiple etiology dementia (see Figure 1-1)—increasingly believed to be the predominant form in older individuals—and limited understanding of the connections among, and joint consequences of, distinct neuropathologies and overlapping clinical presentations and symptomatology results in complexity in the use of these terms both in the clinical and research settings. Such complexity also has consequences for individuals struggling to receive accurate and timely diagnoses and care.

The committee chose to use the terms AD/ADRD and related dementias throughout the report for consistency with its Statement of Task. AD/ADRD refers to all causes of neurodegeneration that are included in the study scope. Consistent with common terminology in the field, the report will also use the term dementia to refer to this group of neurodegenerative diseases. In contrast, related dementias refer to all causes of neurodegeneration that are included in the study scope with the exception of AD. The committee acknowledges concerns that the term related dementias may be viewed as implying that these are secondary in importance to AD and therefore dismissive of the experiences of those living with these diseases. The committee underscores that all forms of neurodegeneration are equally important, and many aspects of the committee’s report are designed to be broadly applicable across all types of dementia. Where discussion is specific

BOX 1-2

Descriptions of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (AD/ADRD): The committee’s task is broadly focused on a group of progressive cognitive disorders, which develop over the life course and are characterized by an acquired loss of cognitive function that influences memory, thinking, and behavior and eventually is severe enough to interfere with independence and daily tasks (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024a,b; NASEM, 2021b). For the purposes of this report and for consistency with the Statement of Task, the term AD/ADRD includes Alzheimer’s disease and the following related dementias: Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, vascular dementia, and multiple etiology dementia. As understanding of the biological basis for this group of diseases continues to evolve, the inclusion and distinction of different disorders that fall under AD/ADRD may change. Brief descriptions of each, including distinguishing features related to brain pathologies and cognitive and behavioral characteristics, are included below.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia: AD is defined by the specific presence and location of amyloid plaque and tau neurofibrillary tangle pathologies (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024b). The condition primarily affects individuals 65 and over. Individuals diagnosed prior to turning 65 are described as having early-onset AD, and some of these will have genetic causes and be referred to as familial AD. Due to an extra copy of chromosome 21, which includes the APP gene, there is another form of early-onset AD called Down syndrome-related AD. Common symptoms of AD include memory loss; difficulty completing familiar tasks; impaired judgment; misplacing objects; changes in mood, personality, or behavior; and, eventually, difficulty walking, talking, and swallowing (CDC, 2020; Alzheimer’s Association, 2024b).

Lewy body dementia (LBD): LBD is associated with abnormal deposits of a protein called alpha-synuclein in certain regions of the brain (e.g., substantia nigra). These deposits, called Lewy bodies, may also be found in other types of dementia, including Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson’s disease dementia (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024c). Clinical symptoms of LBD typically begin to show at age 50 or older and can include visual or auditory hallucinations; changes in concentration, attention, alertness, and wakefulness; severe loss of other cognitive abilities that interfere with daily activities; REM sleep behavior disorder; impaired autonomic function; and impaired mobility with parkinsonian features (e.g., shuffling walk, stooped posture, balance problems and

repeated falls, muscle rigidity, stiffness, tremors) (Lewy Body Dementia Association, 2022).

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD): FTD consists of a group of disorders caused by progressive nerve cell loss in the brain’s frontal or temporal lobes, leading to loss of function in these brain regions and deterioration in behavior, personality, and/or difficulty with producing or comprehending language. Some patients with FTD may also have motor neuron disease (also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or Lou Gehrig’s disease) and vice versa. The two most prominent causes of FTD involve the proteins tau and TDP-43, although there are other types of FTD caused by specific genetic mutations and different protein inclusions. Unlike AD, FTD is more commonly diagnosed in midlife, among people between 40 and 60 years of age (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024d). The three major types of FTD include behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, which involves changes in personality, behavior, and judgment; primary progressive aphasia, which involves changes in the ability to use language to speak, read, write, name objects, and understand what others are saying; and movement disorders, which produce changes in muscle (motor neuron disease) or motor functions (parkinsonism). The latter can include symptoms associated with such atypical parkinsonian disorders as corticobasal syndrome and progressive supranuclear palsy (FTD Talk, 2024). Mixed clinical presentations involving a combination of these symptoms are common in FTD (Alzheimer’s Association, 2021).

Vascular dementia: Vascular dementia is caused by disruptions to vital blood and oxygen supply that also disrupt brain neurotoxin clearance, resulting in neuronal and glial injury and cell death culminating in cogni-

to a particular disease or type of dementia, the specific conditions of relevance are noted.

It is important to acknowledge that dementia in the clinical sense represents the culmination of a progressive process that begins with pathologic changes in the brain that eventually result in cognitive impairment and may also include the development of behavioral, psychiatric, motor, and functional impairments. Over time these impairments may reach a level of severity such that the individual can no longer function independently. Symptoms may progress to the point where individuals may not be able to walk, maintain continence, or even swallow. Ultimately dementia is a fatal condition. For the purposes of this report, the term clinical dementia will

tive decline and impairment. Vascular dementia is characterized by the presence of arteriolosclerosis and neuro-glio-vascular injuries to blood–brain barrier integrity. Cerebrovascular injuries include infarcts (micro or large vessel), hemorrhages (micro or lobar), myelin abnormalities caused by small vessel disease, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Vascular dementia presents with similar symptoms to other types of dementia and can include confusion, challenges with organizing thoughts, difficulty with planning and communication, and physical symptoms such as reduced coordination and unsteady gait. Some but not all patients with vascular dementia may have an abrupt onset caused by stroke or hemorrhage (Linton et al., 2021).

Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE): LATE was clinically recognized in 2019 as a type of dementia that is similar to AD in clinical presentation but involving a distinct pathology characterized by the accumulation of TDP-43 in the limbic system in the brain of older adults, typically among those over the age of 80 years. Symptoms of LATE can include memory loss and impaired cognition and decision making. Misdiagnosis as AD is believed to be widespread, and co-occurrence with other types of dementia is also thought to be common; some patients diagnosed with AD may instead have LATE or a combination of both brain pathologies (Nag and Schneider, 2023).

Multiple etiology dementia: Multiple etiology dementia occurs when two or more pathologies (mixed pathologies) co-occur in the brain of a person living with clinical dementia. The prevalence of such co-occurrence is widespread, and it is thought that most dementia cases among those over the age of 65 years are multiple etiology dementia. Symptoms reflect those associated with the distinct pathologies and may vary based on the type and extent of neuropathological changes present (NINDS, 2024).

be used when referring to impairment that meets the clinical criteria for a diagnosis of dementia.3

Importantly, cognitive impairment exists on a continuum and different people may experience impairment in different cognitive domains (e.g., executive function, memory) (NASEM, 2021a,b). Several different categorizations are commonly applied to describe levels of progressive impairment

___________________

3 Throughout the report the committee endeavored to specify where the research cited was referring to clinical dementia. In some cases, it was not clear from the cited reference whether the authors referred to clinical dementia or a specific cause of dementia. In those cases, the committee used the same terminology as the reference.

NOTE: These data are from 447 participants of the Religious Orders Study and the Memory and Aging Project. Other degenerative (OD) includes neurodegenerative disease pathologies: Lewy bodies, TDP-43, and hippocampus sclerosis. AD = Alzheimer’s disease.

SOURCE: ASPE, 2023.

that do not meet the clinical criteria for dementia. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) denotes a level of deterioration from normal cognitive function that is identifiable (e.g., by the individuals themselves, close contacts, or clinicians) but that does not significantly impair functions related to activities of daily living (McKhann et al., 2011; NASEM, 2017). MCI increases the risk of developing clinical dementia in the future (NIA, 2021). Other categorizations of cognitive decline include age-related cognitive decline (or cognitive aging), which is deterioration in cognitive performance that can be a normal part of aging (NASEM, 2017; Toepper, 2017), and subjective cognitive decline, which is a self-perceived decline in cognitive function in individuals without measurable cognitive decline (Jessen et al., 2020). The development of strategies for primary and secondary prevention of dementia need to consider MCI and the pathologic processes that precede it.4 Thus, the populations of interest to the committee include those with clinical dementia, MCI, and neuropathologic changes in the absence of clinically measurable symptoms.

While probable diagnoses of different forms of dementia have historically been made based on clinical syndromes and confirmed definitively

___________________

4 Primary prevention aims to prevent the onset of a condition and in the context of this report may include those interventions focused on making the brain more resilient and those aimed at preventing underlying processes that result in pathology. Secondary prevention aims to prevent the progression of an asymptomatic or early-stage condition.

postmortem by the observation of pathology at autopsy, the discovery of biomarkers that can be evaluated premortem is enabling the development of a biological definition for Alzheimer’s (Jack et al., 2018) and, potentially, related neurodegenerative diseases (Simuni et al., 2024).5 This allows for the potential diagnosis of disease in the absence of clinical symptomology, as discussed further in Chapter 2. Biomarkers—measurable indicators of biological processes in the body that may be measured through imaging, genetic testing, and testing of blood or cerebrospinal fluid (NIA, 2022)—are not only employed in the prediction and diagnosis of AD/ADRD but are also used in the stratification of populations into subgroups with shared characteristics (i.e., biological subtypes) and to assess response to prevention and treatment strategies.

The committee was charged with examining and assessing the current state of biomedical research aimed at preventing and effectively treating AD/ADRD, including research on pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions. Intervention refers to any program or treatment applied at an individual or population level, including pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches, that is designed to prevent or modify the condition under investigation (NASEM, 2017). The Statement of Task excludes from the study scope research on dementia care and caregiving interventions, including care models (e.g., care coordination). These topics have been the focus of other recent National Academies studies.6 However, the distinction between dementia care and treatment of AD/ADRD was an early point of discussion for the committee, particularly in the context of treatments for neuropsychiatric symptoms—noncognitive core features of AD/ADRD that are included within diagnostic criteria and may include apathy, anxiety, and depression, among others (Cummings, 2021).

Treatments for neuropsychiatric symptoms are commonly classified as care interventions, distinct from disease modifying therapies (DMTs), which are being defined in this report as pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions that can produce a lasting change in the trajectory of AD/ADRD by targeting an underlying pathophysiologic mechanism of the disease that results in cell death (Cummings and Fox, 2017). Applications of DMTs may include both primary and secondary prevention, and DMTs need not be limited to pharmacological treatments; they may also include, for example, nonpharmacological neuroprotective strategies that

___________________

5 A biological definition has been proposed for neuronal alpha-synuclein disease, which would include Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies.

6 Recent analyses of the research landscape related to dementia care and caregiving can be found in Meeting the Challenge of Caring for Persons Living with Dementia and their Care Partners and Caregivers: A Way Forward (NASEM, 2021a) and Reducing the Impact of Dementia in America: A Decadal Survey of the Behavioral and Social Sciences (NASEM, 2021b).

are implemented early in the life course (i.e., childhood, adolescence, and midlife) to prevent pathophysiologic processes. Given the current incomplete neurobiological understanding of AD/ADRD, the distinction between DMTs and treatments for neuropsychiatric symptoms may not be as clear as may be assumed.

An association between neuropsychiatric symptoms and acceleration in cognitive decline has been widely reported in the literature (Burhanullah et al., 2020; David et al., 2016; Defrancesco et al., 2020; Pink et al., 2023), although questions remain regarding the role of reverse causality (i.e., the contribution of cognitive decline to neuropsychiatric symptoms). Consequently, there is likely some overlap in interventions aimed at improving the well-being of persons living with AD/ADRD by seeking to alleviate such neuropsychiatric symptoms as depression and anxiety and interventions aimed at preventing, delaying, or slowing the progression of AD/ADRD. Given their potential to not only change the trajectory of disease but also to improve quality of life, reduce care costs, and enable persons living with AD/ADRD to remain in their homes or with family care partners and caregivers, the committee included in its evaluation of promising interventions those therapeutic approaches targeting neuropsychiatric symptoms that may also result in the preventing, delaying, or slowing of AD/ADRD.

In examining the state of the science and identifying research priorities to advance the prevention and treatment of AD/ADRD, the committee was asked to consider research spanning basic, translational, and clinical phases of the continuum. While the development of recommendations related to the implementation and scaling of tools and interventions in clinical practice and community settings was outside the study scope, the committee recognizes that the research and development pipeline is not linear and unidirectional. Lessons from real-world implementation feed back to inform future research and guide the development of new or modified tools, technologies, and intervention strategies for AD/ADRD prevention and treatment. With this in mind, the committee included in its examination of the research landscape opportunities to integrate implementation considerations early in the research and development process and to incorporate real-world evidence following implementation into the research pipeline. As the field advances and novel tools and interventions are developed and approach readiness for implementation, a deeper review of strategies and priorities for implementation in an impactful and equitable manner may be needed.

Consistent with the Statement of Task, this report focuses on the state of the science and research priorities for the prevention and treatment of AD/ADRD. However, the committee acknowledges that there are broader forces at play that impede access to effective prevention and treatment, including the need for a robust and diverse clinical workforce that has the training and capacity to deliver interventions and provide compassionate

and high-quality care. While the committee was not asked to make recommendations related to the provision of care, it is within the scope of the committee’s work to examine opportunities to develop tools and technologies that can enable the clinical workforce to detect, accurately diagnose, and continuously monitor AD/ADRD and select effective prevention and treatment strategies.

A final critical point regarding the study scope relates to the timescale indicated in the Statement of Task, which specifies that the committee should identify near- and medium-term scientific questions that may be addressed through NIH funding over the next 3 to 10 years. The committee interpreted this to mean that it should identify research areas that should be a high-priority focus over the next decade but not necessarily brought to completion within that time frame. Science evolves in a nonlinear, iterative manner, and there is still a great deal we still do not understand about the basic disease processes for AD/ADRD. Moreover, the building of necessary infrastructure and resources (e.g., research cohorts) is a time-intensive endeavor. While some goals may take more than a decade to realize, it is important to emphasize that this does not reflect a lower urgency than those that may be more reasonably achieved within the next 10 years.

STUDY CONTEXT

AD/ADRD Research at an Inflection Point

The AD/ADRD field stands at a crossroads—there is a palpable sense that decades of scientific inquiry and more recent increased investment in research are near to paying off with significant advances in diagnostic and intervention capabilities, generating excitement and momentum. Still, the juxtaposition of the near-term future potential and the current reality is striking. In the wake of recent approvals of new drugs for AD, there is growing hope regarding the ability to prevent and slow the progression of early disease through intervention, but even the modest benefits provided by these drugs apply only to a small proportion of the target population and little progress has been made toward effective treatments for those living with advanced disease and related dementias. Similarly, cutting-edge tools and technologies such as fluid and digital biomarkers, multiomic methods, and artificial intelligence are poised to radically change the research and clinical practice landscape, but some current tools for fundamental clinical cognitive assessments are not able to detect early, more subtle changes in cognition and are, in some cases, biased, posing barriers to linking emerging diagnostics to clinical outcomes.

An Urgent and Growing Need for Effective Prevention and Treatment Approaches

Few diseases have affected society on the scale at which AD/ADRD is exacting an emotional and financial toll for individuals, families, and communities. While the effects of dementia in terms of mortality, disability, and financial burden are staggering, no less devastating are its profound effects on the lives, livelihoods, and relationships of those affected by the disease. While every person will have a unique experience of dementia influenced by their individual context (NASEM, 2021a,b), for many, the suffering caused by dementia is further exacerbated by stigma, which stems in part from the fear and distress that often accompany diagnosis, particularly in the absence of effective treatments.

Currently, there are more than 6 million people living with clinical dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease in the United States (Manly et al., 2022) and more than 55 million people living with the dementia globally; the World Health Organization has recognized dementia as a global public health priority (WHO, 2023). Based on National Health Interview Survey data from 2022, 4 percent of adults in the United States self-reported having received a diagnosis of dementia, including AD, from a clinician. This proportion increased with age from 1.7 percent of respondents ages 65–74 years confirming a diagnosis of dementia to 13.1 percent among respondents age 85 years and older (Kramarow, 2024). Accurate data on the prevalence and incidence of the different types of dementia are lacking in part because these measures are reliant on the diagnostic definitions in use, which poorly account for related dementias and the presence of mixed pathologies. Measures such as cumulative lifetime incidence, which describe the probability that an individual will be affected by a clinical syndrome before their death, may provide a better understanding of the public health impact and inequities of AD/ADRD across the population. One prospective study in a diverse Northern Californian cohort reported a cumulative 25-year risk of clinical dementia (including AD, vascular dementia, and nonspecific dementia) at age 65 of 38 percent for African Americans, 35 percent for American Indians and Alaska Natives, 32 percent for Latinos, 25 percent for Pacific Islanders, 30 percent for Whites, and 28 percent for Asian Americans (Mayeda et al., 2016).

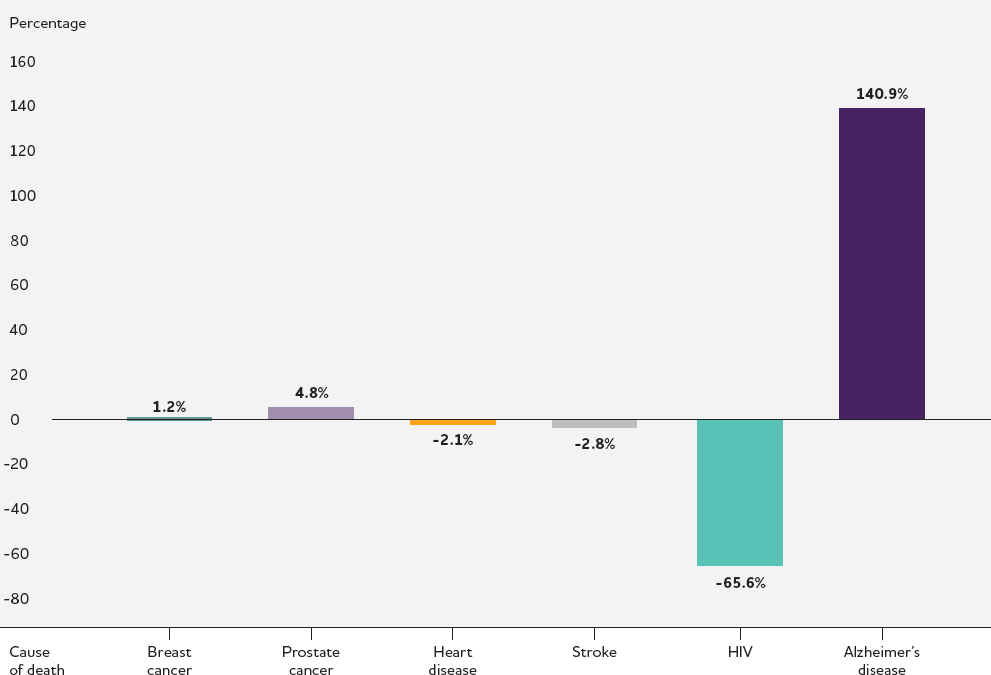

While deaths from some other major causes of mortality in the United States decreased or remained stable over the last 2 decades, deaths from AD more than doubled during this period (see Figure 1-2).7 These phenomena are likely linked—increasing life expectancies resulting from progress

___________________

7 Note that the accuracy of death certification for dementia has improved over time, but the reporting of dementia as a cause of death likely remains underreported based on the rate of clinical diagnosis (Adair et al., 2022).

NOTE: Data collected by the National Center for Health Statistics from death certificates listing Alzheimer’s disease as an underlying cause of death. No information available on how cause of death determinations were made or whether other neuropathologies were present.

SOURCE: Alzheimer’s Association, 2023.

reducing mortality from chronic conditions increases the lifetime risk of developing dementia (Zissimopoulos et al., 2018). Recent models predict that the number of older Americans (ages 65 and older) living with dementia will grow to nearly 12 million in 2040 in the absence of a change to the status quo (Zissimopoulos et al., 2018).

It is also well established that the impacts of dementia are not experienced uniformly across populations. In the United States, racial and ethnic disparities in dementia prevalence continue to persist; as compared to non-Hispanic White people, Black and Hispanic people are more likely to develop clinical dementia (Chen and Zissimopoulos, 2018). The lifetime risk of AD-type dementia for women has been estimated to be about twice that of men, but gender differences in risk may vary by dementia type; the incidence of vascular dementia, for example, is higher in men than in

women in people 55–75 years of age (Mielke, 2024). Sex and gender differences in AD/ADRD are further discussed in Box 1-3. Social determinants of health significantly affect rates of dementia, as evidenced by increased AD/ADRD prevalence rates in lower-income and rural areas (Powell et al., 2020; Wing et al., 2020).

While these statistics are sobering, there is growing evidence of declining dementia prevalence and incidence in high-income countries (Farina et al., 2022; Wolters et al., 2020).8 The prevalence of U.S. adults ages 70 years and older living with dementia declined between 2011 and 2019 from 13 percent to 9.8 percent (Freedman et al., 2021); however, it remains unclear to what degree different factors are driving that decline and to what degree the trends will continue. Additionally, as the baby boom generation continues to reach ages at which the risk of dementia significantly increases, the absolute number of people with dementia will continue to rise, along with the societal burden.

The estimated global societal cost of dementia in 2019, including the financial burden associated with unpaid caregiving, was more than $1 trillion (Wimo et al., 2023), although this is likely an underestimate. By 2030, total annual costs associated with dementia are estimated to rise to $624 billion in the United States alone (Zissimopoulos et al., 2014). Dementia cost estimates typically include medical costs and the cost of long-term services and support, as well as some indirect costs such as the value of unpaid caregivers’ time for caring for persons living with dementia. Estimates of dementia costs, when based on a limited set of cost inputs, is likely a significant underestimate, particularly as it relates to costs associated with unpaid care provided by family and friends. Time spent caregiving may result in productivity losses and future income and wealth losses, and caregivers may experience challenges to their own health, quality of life, and finances associated with the challenges of caregiving. There may be other hidden costs, such as those associated with treatments, trial participation, or financial exploitation. Importantly, the costs of dementia are not static, and estimates require annual updates and consideration of health, treatment innovation, care, and cost dynamics to be useful for planning and prioritizing (Zissimopoulos et al., 2014).

Given the demographic shifts that are expected to occur in the coming decades, including the doubling of the population of older adults, the development of effective approaches for the prevention and treatment of AD/ADRD is of great importance to people at risk for dementia and those living with the disease, their family members, caregivers, and communities,

___________________

8 Prevalence is the proportion of a population with the characteristic of interest at a specific point in time (NIMH, 2024). Incidence is the rate of new cases in a defined population occurring over a given period of time (Tenny and Boktor, 2023).

BOX 1-3

Sex and Gender Differences in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (AD/ADRD)

Sex and gender differences have been observed for many aspects of AD/ADRD (e.g., epidemiology, risk factors, treatment effects). Sex (a biological construct related to genetics, anatomy, and physiology) and gender (a social construct) are often used interchangeably. However, many factors have both sex and gender components, and it is often challenging to tease apart the relative contributions of each (Mielke, 2024).

Differences between men and women in the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia have been reported across many studies (Andersen et al., 1999; Beam et al., 2018; Ruitenberg et al., 2001), although the literature is inconsistent (Kawas et al., 2000; Mielke et al., 2022; Wolters et al., 2020). The observation of gender differences in dementia risk varies across countries, and it remains unclear how much of this difference is due to the greater longevity of women as compared to men and the contributions of other sociodemographic factors (e.g., education and occupational opportunities) (Huque et al., 2023). Gender differences in dementia incidence also vary by dementia type (Akhter et al., 2021; Lucca et al., 2020).

In addition to risk, sex and gender differences in disease trajectory have also been reported. As a result of better baseline cognition in memory-related domains, women may be diagnosed with amnestic forms of dementia later and may therefore appear to progress to dementia more quickly as compared to men (Lin et al., 2015; Nebel et al., 2018). It has also been proposed that women’s resilience to neuropathology may change over the course of disease progression, with diminished resilience at later stages resulting in steeper cognitive declines as compared to men (Arenaza-Urquijo et al., 2024).

Potential explanations for observed differences in AD/ADRD between men and women include a combination of biological (e.g., genetics, pregnancy, menopause) and sociocultural factors (e.g., caregiving roles, occupational opportunities) (Mielke, 2024). Such factors may contribute to sex and gender differences in certain AD/ADRD risk factors, such as cardiometabolic disorders (Gerdts and Regitz-Zagrosek, 2019; Ramirez and Sullivan, 2018), depression (Artero et al., 2008; Kessler et al., 1993; Kim et al., 2015), and physical inactivity (Barha et al., 2020; Luchsinger, 2008). Moreover, some well-established determinants of cognitive resilience, such as education, have historically had a large gender component (Gilsanz et al., 2021).

Understanding of sex and gender differences in AD/ADRD and intersections with other factors such as race/ethnicity and cultural identity has been hampered by inadequate attention to the consideration of sex and gender in the design, execution, analysis, and reporting of research. While representation of women in clinical studies has improved and studies are increasingly adjusting for gender, relatively few studies analyze data for or report differences by sex and gender, despite the existence of an NIH policy requiring the consideration of sex as a biological variable (Mielke, 2024). Taking a more sex- and gender-aware approach to AD/ADRD research will not only help elucidate sex- and gender-differences in risk, resilience, and clinical progression, but is also needed to understand differences in the efficacy of interventions and inform precision medicine approaches.

as well as policy makers, clinicians, and social services providers, and society as a whole.

Reasons for Optimism

In June 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the monoclonal antibody-based drug aducanumab for the treatment of AD (Cavazzoni, 2021).9 While the approval of the drug under the agency’s accelerated approval pathway was controversial,10 it was also notable as the first drug approved for treatment of AD in nearly 2 decades and the only approved drug (at that time) targeting an underlying pathophysiologic process—specifically, the accumulation of amyloid beta. While aducanumab’s manufacturer announced that the drug would be discontinued in 2024 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024e), the approval of two additional amyloid-targeted antibody-based drugs followed shortly after

___________________

9 In July 2024, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended the refusal of the marketing authorization for lecanemab because the benefits did not outweigh the risk of serious adverse effects. EMA raised concerns that the risk of serious adverse effects may be heightened in people who are carriers of the APOE4 gene variant (EMA, 2024).

10 The accelerated approval pathway enables FDA to approve a drug for a serious or life-threatening illness based on the drug’s effect on a surrogate endpoint that is likely to predict a meaningful clinical benefit to patients (beyond the benefits that may be achieved through existing treatments) even if there remains some uncertainty about the drug’s therapeutic benefit (Cavazzoni, 2021).

aducanumab. In January 2023, lecanemab received accelerated approval by FDA for treatment of AD, which was converted to a traditional approval in July of that year based on the results of a confirmatory study verifying clinical benefit (FDA, 2023). In contrast to aducanumab, which was determined to have insufficient evidence that the drug was reasonable and necessary (AlzForum, 2022), the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) decided to broadly cover lecanemab under Coverage with Evidence Development (CED) following FDA traditional approval (CMS, 2023).11 Most recently, donanemab was approved in July 2024.

Amyloid-targeted antibody-based drugs are not a panacea. The clinical benefits, which were evaluated in research participants in the early stages of AD, have been modest, and there are significant risks to the treatment (Budd Haeberlein et al., 2022; Sims et al., 2023; van Dyck et al., 2023), as discussed further in Chapter 4. High costs and a health care system unprepared to deliver such intravenous infusion therapies are major barriers to translation into clinical practice on a scale commensurate with the burden of disease (Mattke et al., 2024). For example, annualized per-beneficiary medication costs for lecanemab were estimated at $25,851 for Medicare beneficiaries with an additional $7,330 in ancillary costs (e.g., infusions, imaging). Annual out-of-pocket costs for individual beneficiaries may be in the thousands of dollars (Arbanas et al., 2023). Importantly, anti-amyloid antibody-based therapeutics are not relevant to other forms of dementia that do not involve the accumulation of amyloid plaques, such as frontotemporal and Lewy body dementia, for which there remain no approved treatments beyond those for managing symptoms.

Despite their limitations, the availability of approved therapies for AD has given rise to optimism among patients and researchers that AD and related neurodegenerative disorders can be treated to slow or halt disease progression and perhaps even prevented. It is also driving renewed interest in investment in AD/ADRD drug development, interest that had waned in the face of a high clinical trial failure rate (98 percent over the last 2 decades) (Cummings, 2018; Kim et al., 2022; Mehta et al., 2017; WHO, 2021). The creation of NIH-funded research initiatives to diversify the drug development pipeline, such as the Accelerating Medicines Partnership® Program for Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD) consortium and the Target Enablement to Accelerate Therapy Development for Alzheimer’s Disease (TREAT-AD) centers (discussed further in Chapter 3), have resulted in the nomination of over 900 potential targets for further therapeutic development for AD (Agora, 2024). Similar initiatives (e.g., the Accelerating

___________________

11 Under Coverage with Evidence Development (CED), the treating clinical team must contribute to the collection of evidence on how the therapeutics work in the real world through participation in a CMS registry (CMS, 2023).

Medicines Partnership® Program for Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders) are driving advances for other dementia types. Additionally, with ongoing private-sector investments in treatments for AD/ADRD and the expansion of public–private partnerships (Cummings et al., 2021), new waves of therapies could emerge in the next decade.

Over the last decade, significant advances have been made in the understanding of modifiable risk factors (e.g., physical inactivity, hypertension, diet, social isolation) common across multiple types of dementia. Based on these modifiable risk factors, it has been estimated that approximately 40 percent of dementia cases may be preventable (Livingston et al., 2020, 2024). Additionally, interventions that target modifiable risk factors (i.e., healthy behaviors) may extend the number of healthy years of life and, among those who do ultimately develop dementia, compress the number of years living with disease (Livingston et al., 2024). Findings such as these have opened new opportunities for the development and evaluation of multicomponent intervention approaches that are designed to simultaneously target multiple factors common across AD/ADRD and be implemented in combination with other therapeutics (discussed further in Chapter 4).

The use of innovative randomized controlled trials to assess the cognitive and quality-of-life effects of these lifestyle and health behavior interventions in diverse populations, such as the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability and the Systematic Multi-domain Alzheimer’s Risk Reduction Trial, have demonstrated the potential and feasibility of these study designs and interventions and are continuing to expand understanding of how these approaches can be optimized for maximum benefit based on individual and population preferences and characteristics (Ngandu et al., 2015; Yaffe et al., 2024). The continuation of this work may realize opportunities in the near and medium term to accelerate tailored AD/ADRD prevention and resilience-building efforts at individual and population levels.

Additionally, intensive research on the development of biomarkers, particularly for AD, have led to a number of exciting advances poised to radically change the research and clinical practice landscape. Advances in the development and validation of fluid, imaging, and digital biomarkers are allowing for better linking of interventions to target populations and measurement of intervention response. Developing tools such as blood-based biomarkers and digitally based assessments may provide for earlier detection of changes in brain health as compared to traditional cognitive assessments and reduce reliance on invasive and expensive tests. For the first time, a blood test is now commercially available for AD based on blood amyloid levels and a plasma phospho-tau biomarker has been demonstrated to be clinically equivalent to FDA-approved cerebrospinal fluid biomarker tests used to detect AD pathology (Barthelemy et al., 2024). While not yet

available clinically, ongoing research is exploring biomarkers available for alpha-synuclein and TDP-43 pathologies. As additional biomarkers are discovered and validated, particularly for related dementias, current barriers to early detection, diagnosis, prognosis (e.g., the likelihood of progression to clinical dementia), and longitudinal monitoring may be overcome, and it will be possible to quantify and better understand multiple etiology dementia.

These past successes, among others, provide the foundation to accelerate future scientific and clinical progress. There is significant opportunity and need to expand the repertoire of interventions that can be used to effectively treat AD/ADRD and ultimately prevent disease development. Investments in basic mechanistic and epidemiological research have yielded returns in an expanded set of targets now being evaluated in clinical trials, as well as other breakthroughs, such as the development of blood-based biomarkers that hold promise for early diagnosis and precision medicine approaches (Sarkar et al., 2024). Such advances are poised to transform the landscape for AD/ADRD research.

The Role of NIH in Advancing AD/ADRD Research

Strategic Planning Guided by the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease

The enactment of the National Alzheimer’s Project Act in 2011 provided an unprecedented opportunity to undertake a national-level strategic planning initiative aimed at addressing the challenges of AD/ADRD. The Act required the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to work collaboratively with the newly established Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services to create and maintain a National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease (National Plan) (HHS, 2024). The first National Plan was released in 2012 and has since been updated annually, with these efforts led by the HHS Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE). Three overarching principles have guided each iteration of the National Plan:

- Optimize existing resources, and improve and coordinate ongoing activities.

- Support public–private partnerships.

- Transform the way we approach AD/ADRD (HHS, 2024).

The National Plan includes six foundational goals, the first of which—of particular relevance to this committee’s report—is “Prevent and effectively treat Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias by 2025” (HHS,

2024).12 Interim milestones developed by HHS help to track progress toward achieving this goal (HHS, 2024). For each goal, the National Plan specifies individual strategies and associated action steps (see Box 1-4 for the strategies under Goal 1 and Goal 6, which are most closely linked to the committee’s charge). The National Alzheimer’s Project Act was reauthorized in October 2024, supporting the continuation of efforts to meet the six foundational goals of the National Plan until 2035.13

NIH has a lead role in research efforts supporting the goals of the National Plan, with a particular emphasis on Goal 1 (HHS, 2024; Kelley, 2023). While multiple institutes, centers, and offices within NIH are engaged in efforts to achieve the research goals of the National Plan, NIA and NINDS are leading many of the action steps, with NIA generally leading efforts related to Alzheimer’s disease and with NINDS focused on related dementias.

To support the identification of research priorities, NIH convenes annual research summits, the focus of which rotates among Alzheimer’s disease (led by NIA); related dementias (led by NINDS); and research on care, services, and supports for persons living with dementia and their care partners/caregivers (led by NIA) over a 3-year period. These summits serve as key opportunities to gather broad input for NIH’s strategic planning efforts (depicted in Figure 1-3) and ensure that scientific input is gathered from diverse multisector partners and participants to inform the development of an integrated, comprehensive research agenda (Kelley, 2023). In addition to showcasing progress to date, the summits serve to identify research gaps, bottlenecks that impede progress, priorities, and opportunities to translate AD/ADRD research findings into practice. In addition to the summits, NIH gathers input from the external community through various other forums, including workshops, meetings, and other activities.

NIH research priorities are outlined as a series of research implementation milestones (NIA, 2024a), which identify activities to address the goals of the National Plan and together form a blueprint for an integrated research agenda. Success criteria and specific implementation steps are defined for each milestone, and progress is tracked through a publicly available AD/ADRD milestone database. The milestones are updated annually based on the input from the summits and other sources, including National Academies reports and NIH-hosted workshops, among others (Kelley, 2023). At present there are more than 200 milestones in the AD/ADRD research implementation milestone database that are divided among

___________________

12 Goals 2–6 of the National Plan are: 2. Enhance Care Quality and Efficiency; 3. Expand Supports for People with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias and Their Families; 4. Enhance Public Awareness and Engagement; 5. Improve Data to Track Progress; and 6. Accelerate Action to Promote Healthy Aging and Reduce Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (HHS, 2024).

13 NAPA Reauthorization Act, Public Law 118-92, 118th Cong. (October 1, 2024).

BOX 1-4

Strategies for Goals 1 and 6 of the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease

Goal 1 of the National Plan is to “Prevent and Effectively Treat Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias by 2025” and includes five strategies, listed below, each accompanied by a series of action steps.

Strategy 1.A: Identify research priorities and milestones.

Strategy 1.B: Expand research aimed at preventing and treating Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias.

Strategy 1.C: Accelerate efforts to identify early and presymptomatic stages of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias.

Strategy 1.D: Coordinate research with international public and private entities.

Strategy 1.E: Facilitate translation of findings into medical practice and public health programs.

Goal 6 of the National Plan is to “Accelerate Action to Promote Healthy Aging and Reduce Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias” and includes six strategies, listed below, each accompanied by a series of action steps.

Strategy 6.A: Identify Research Priorities and Expand Research on Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias.

Strategy 6.B: Facilitate Translation of Risk Reduction Research Findings into Clinical Practice.

Strategy 6.C: Accelerate Public Health Action to Address the Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias.

Strategy 6.D: Expand Interventions to Reduce Risk Factors, Manage Chronic Conditions, and Improve Well-Being Through the Aging Network.

Strategy 6.E: Address Inequities in Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias Among Marginalized Populations.

Strategy 6.F: Engage the Public About Ways to Reduce Risks for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias.

SOURCE: HHS, 2024.

six research categories spanning basic, translational, clinical, and health services research:

- Epidemiology/population studies

- Disease mechanisms

- Diagnosis, assessment, and disease monitoring

- Translational research and clinical interventions

- Dementia care and impact of disease

- Research resources (NIA, 2024a)

The research blueprint formed by the milestones guides NIH funding opportunities but is also used for other purposes, such as informing priorities for cultivating partnerships and collaborations.

NIH Support for AD/ADRD Research

As noted earlier in this chapter, congressional appropriations related to AD/ADRD increased substantially following the enactment of the National Alzheimer’s Project Act, resulting in a significant expansion of NIH investment in AD/ADRD research. While relative funding increases from fiscal year (FY) 2015 to FY2022 for specific related dementias were similar to and in some cases exceeded those for AD, absolute funding for AD represents the vast majority of support for AD/ADRD research (see Table 1-1). Some funding categorized as dedicated to AD research may also benefit and apply to related dementias, such as in the case of research on shared underlying mechanisms.

The vast majority of NIH funding support for AD/ADRD research comes from NIA (approximately $3.2 billion in FY2022), followed by NINDS (approximately $127.7 million in FY2022) (NIH RePORT, 2024).14 Other institutes and offices that ranked within the top five for funding AD/ADRD research in FY2022 include the Office of the Director; the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. While NIA provides the majority of the funding for AD research, NIA and NINDS both provide significant funding for research on related dementias (approximately $607.3 million and $84.6 million, respectively in FY2022) (NIH RePORT, 2024).

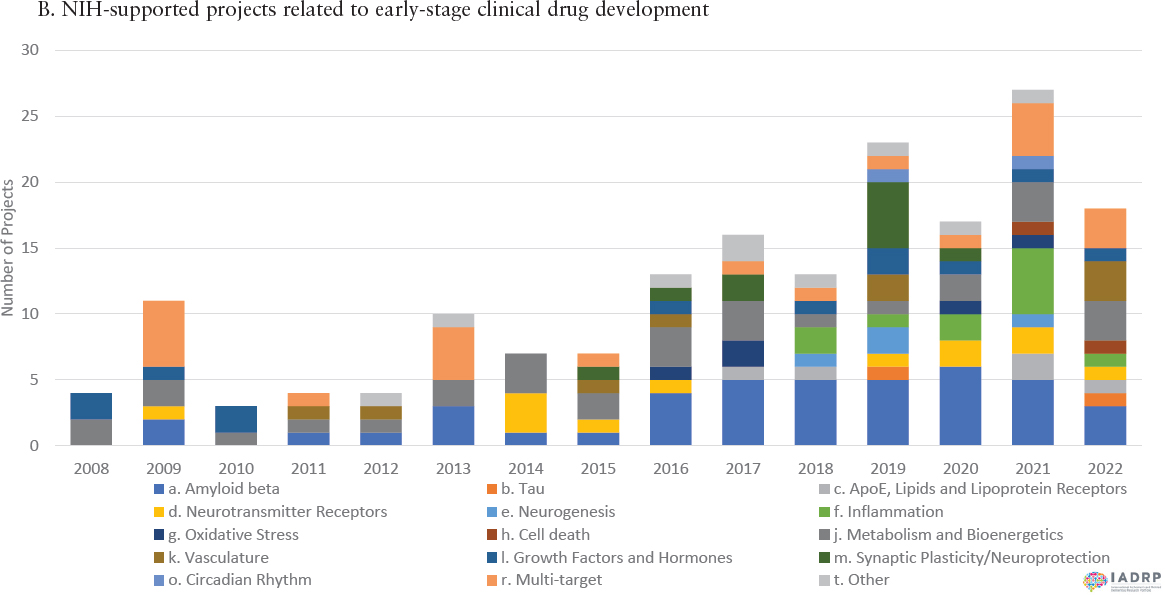

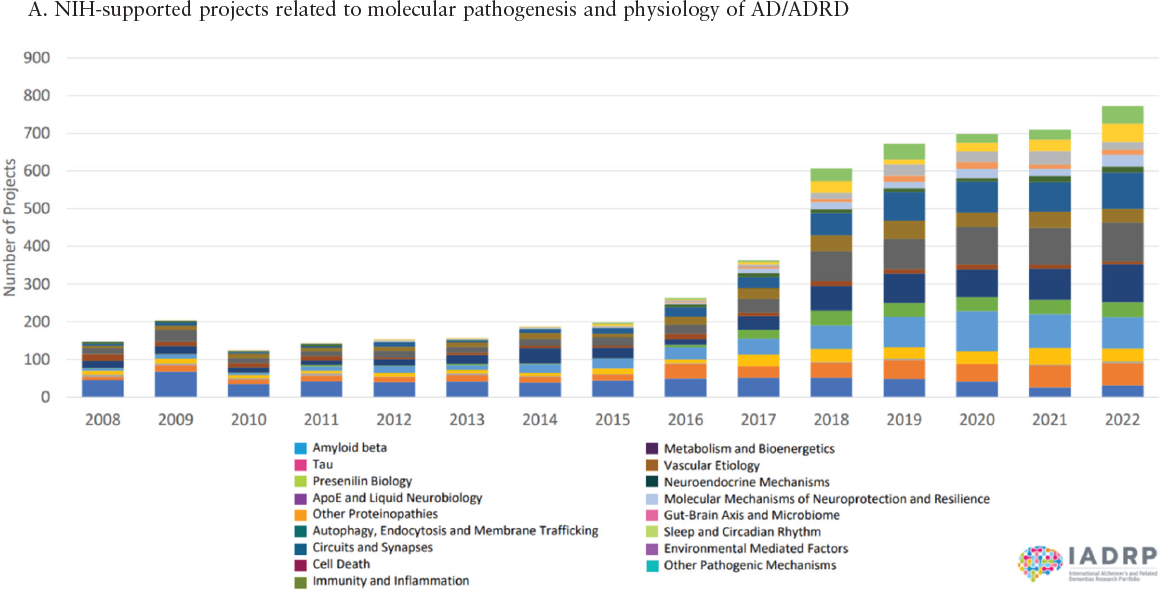

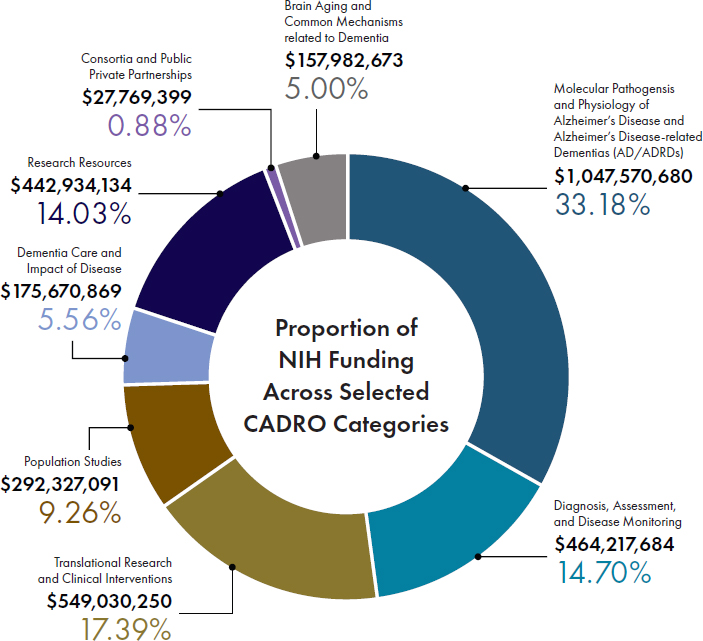

With increased appropriations from Congress, NIH has in the last decade significantly expanded its portfolio of supported projects across the full continuum of basic to clinical research, both in terms of numbers and diversity of projects, as exemplified by the graphs in Figure 1-4. Figure 1-5 shows the distribution of NIH funding for FY2022 across the eight Common Alzheimer’s Disease Research Ontology Research Categories, which cover various aspects of basic, translational, and clinical research. These investments are complemented by support provided by

___________________

14 FY2022 funding levels from individual NIH institutes, centers, and offices were obtained through the selection of relevant Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) categories—Alzheimer’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease Related Dementias (ADRD), and Alzheimer’s Disease including Alzheimer’s Disease Related Dementias (AD/ADRD)—in the RCDC system, which can be accessed at https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending#/.

TABLE 1-1 AD/ADRD Spending at NIH for Fiscal Years 2019 to 2022

| Research/Disease Areas | FY2015 | FY2016 | FY2017 | FY2018 | FY2019 | FY2020 | FY2021 | FY2022 | Difference – FY2015 to FY2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD/ADRDa | $631 | $986 | $1,423 | $1,911 | $2,398 | $2,869 | $3,251 | $3,514 | 5.6-fold increase |

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) | $589 | $929 | $1,361 | $1,789 | $2,240 | $2,683 | $3,059 | $3,314 | 5.6-fold increase |

| Alzheimer’s disease related dementias (ADRD)b, c,d | $120 | $175 | $249 | $387 | $515 | $600 | $725 | $730 | 6.1-fold increase |

| Lewy body dementia | $15 | $22 | $31 | $38 | $66 | $84 | $113 | $118 | 7.9-fold increase |

| Frontotemporal dementia | $36 | $65 | $91 | $94 | $158 | $166 | $164 | $169 | 4.7-fold increase |

| Vascular cognitive impairment/dementia | $72 | $89 | $130 | $259 | $299 | $362 | $455 | $445 | 6.2-fold increase |

NOTE: Funding levels are shown as U.S. dollars in millions

a The category Alzheimer’s Disease including Alzheimer’s Disease Related Dementias (AD/ADRD) reflects the sum of the two existing Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) categories—Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Alzheimer’s Disease Related Dementias (ADRD)—where duplicates are removed.

b The category ADRD reflects the sum of three existing RCDC categories—Frontotemporal Dementia, Lewy Body Dementia, and Vascular Cognitive Impairment/Dementia—where duplicates are removed.

c These categories were established pursuant to Section 230, Division G of the Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act of 2015 as related to reporting of NIH initiatives supporting the National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA), https://aspe.hhs.gov/national-alzheimers-project-act.

d NIH uses the term Alzheimer’s disease-related dementia (ADRD) in some contexts.

SOURCE: Kelley, 2023.

SOURCE: IADRP, 2024.

other funders within the research enterprise, including private industry and philanthropic groups.15 As discussed later in this report, public–private partnerships, such as AMP-AD,16 are increasingly bridging gaps at the interface of basic, translational, and clinical research, thereby helping to accelerate breakthroughs in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of

___________________

15 AD/ADRD research supported by public and private organizations in the United States and abroad is captured in the International Alzheimer’s and Related Dementias Research Portfolio (IADRP), a searchable database available at https://iadrp.nia.nih.gov/ (accessed January 11, 2024).

16 AMP-AD is a public–private partnership between NIH, FDA, private industry, and nonprofit organizations focused on developing new diagnostics and treatments by working collaboratively to identify and validate promising biological targets (NIA, 2024b).

AD/ADRD. The expansion of funding support for AD/ADRD research to levels more commensurate with the scope of the problem has opened new opportunities and avenues for scientific breakthroughs that may not have been possible in a more resource-limited environment. Still, the importance of sustaining these research investments is apparent when considering the scope of dementia research relative to that of cardiovascular disease and cancer. For example, a search of clinicaltrials.gov yielded 272 active (nonrecruiting) dementia-focused clinical trials. In comparison, the number of trials for cardiovascular disease and cancer were near to 2,500 (nearly 10-fold higher) and 7,700 (nearly 30-fold higher), respectively (ClinicalTrials.gov, 2024a,b,c).17

The diversification of the NIH research portfolio, which has been guided by the strategic planning processes described above, reflects a paradigm shift that has emerged with the growing understanding of the scientific community regarding the complex, multifactorial nature of AD/ADRD. The committee was not asked to comprehensively catalog and assess NIH’s programmatic activities related to AD/ADRD or to evaluate and make recommendations on the current strategic planning process used by NIH to set priorities. Rather this report is intended to complement those efforts, highlighting opportunities to accelerate the translation of discoveries emerging from the vast and growing body of knowledge on AD/ADRD into effective strategies for prevention and treatment. This report provides the committee’s consensus views on the research areas with the greatest promise to catalyze significant advances and maximize return on investment in the form of improved population health.

STUDY APPROACH

To address the Statement of Task, the National Academies convened a 19-member committee of individuals with expertise spanning basic to clinical research and covering different aspects of AD/ADRD, including risk factors and epidemiology, biological mechanisms and intervention strategies, clinical trial design and implementation, precision medicine, health economics, and lived experience. Biographies of the committee members can be found in Appendix B.

___________________

17 The search of clinicialtrials.gov for dementia, cardiovascular, and cancer trials did not restrict the results to trials of interventions for disease prevention and treatment. These cited numbers may therefore include trials on care interventions (e.g., care coordination) and other interventions not applicable to the scope of this report.

Guiding Themes

Early in the study process, the committee converged around a life-course approach to addressing the Statement of Task, consistent with another recent dementia-focused National Academies report (NASEM, 2021b), and applied this lens throughout the course of its work. The life-course approach is grounded in the understanding that aging is not something that just happens in the later decades of life—it happens across the entire lifespan. Brain functions change over time as a reflection of the biological development stage it is in. Moreover, the growing body of evidence related to risk and protective factors for AD/ADRD has increasingly been shifting focus to earlier life stages, even as early as the prenatal period (Boots et al., 2023).

In the context of a life-course approach, the committee sought to balance the conventional disease-focused medical model with a framing around optimization of brain health and functioning at every life stage (WHO, 2022). Outcomes of the disease-focused approaches that have dominated both research and clinical practice have included growing health care costs and lower-quality health. With this health-oriented reframing, prevention of disease can be viewed as an incidental benefit of focusing on brain health optimization rather than its primary objective.

Health equity is another theme that guided the committee’s approach and intersects with the life-course framework. As depicted in Figure 1-6, health disparities—systemic, structural, contextual, and individual—have a cumulative effect on outcomes of AD/ADRD over the life course (NINDS, 2022). Applying a health equity lens helped the committee to more intentionally consider the effect of health disparities on outcomes related to optimizing brain health and preventing and treating AD/ADRD and to highlight intervention strategies with the greatest potential to address those disparities.

The application of a health equity lens to the development of this report included consideration of health research equity, and specifically, the underrepresentation of different population groups in AD/ADRD research. Diversity and inclusion in research are critical for high-quality science and important to ensure that the research serves all individuals. Diversity in research is inclusive of a broad array of factors that include but are not limited to race, ethnicity, sex, gender, sexual orientation, age, socioeconomic status, language, education, and profession. Historically many groups underrepresented in research have also been disproportionately affected by AD/ADRD and thus merit special prioritization in future research. For some groups, there is simply too little evidence currently available to know if they are disproportionately burdened by AD/ADRD, so these groups also merit prioritization in future research. Throughout this report, the committee thus

SOURCE: NINDS, 2022.

refers to “understudied and/or disproportionately affected populations” to emphasize the importance of expanding the evidence base for groups historically missing from AD/ADRD research and ensuring commitment to inclusion for groups with known disparities.

One additional aspect of health research equity that warrants attention is the imbalance in research among different types of dementias. As noted earlier in this chapter (see Table 1-1), the majority of funding support for AD/ADRD research has been focused on AD and, as a result, the literature base examined by the committee is similarly biased. This imbalance in research investment is to some degree reflected in the presentation of evidence in this report, although the committee endeavored to balance examples from AD research with examples for related dementias throughout. The continuation of increased focus on understudied related dementias will hopefully address such imbalances in the future, enabling a better understanding of these conditions as well as mixed etiology dementia.

The final theme that guided the committee in its deliberations is the imperative to innovate and to learn from successes and failures in

biomedical research, both within and outside the AD/ADRD field. Innovation is inherently high risk, but failures hold equal potential as successes for expanding knowledge when embraced as an integral part of the scientific process and carefully deconstructed to extract insights. Ultimately, breakthroughs emerge when innovation enables us to break out of what is already being done. Other fields (e.g., cardiology, cancer) are well ahead of dementia in terms of prevention and precision medicine,18 which is an evolving platform of health care delivery that “integrates investigation of mechanisms of disease with prevention, treatment, and cure, resolved at the level of the individual” (NAM, 2017). Such approaches will likely guide the next 10 years of medical research in AD/ADRD and other disease fields. The committee sought to understand the factors that led to paradigm shifts in those fields, to build from their successes, and to learn and apply effective strategies for translating failures into knowledge and progress.

Approach to Identifying Promising Areas of Research

The committee was charged with reviewing and synthesizing the most promising areas of research into preventing and treating AD/ADRD. To address this element of its task, the committee established criteria for different facets of what it could mean for research to be considered “promising.” These were not intended as a checklist or a rigid rubric for evaluation but as a tool to shape the committee’s thinking. As the committee explored and assessed the AD/ADRD research landscape, its efforts to identify promising research areas were guided by the following criteria:

- Multidisciplinary research that has the potential to open new lines of scientific inquiry and build on the successes of other fields;

- Research that maximizes inclusivity and minimizes exclusion as part of its methodology;

- Research that establishes baselines that would allow detection of differences across and within diverse populations and the identification of understudied and/or disproportionately affected populations;

___________________

18 The goals of precision medicine are often interpreted through the lens of the disease- and treatment-focused medical model. Precision medicine in fact has a much broader scope that is inclusive of prevention and population-health approaches. The committee adopted this broader view that is aligned with the brain health optimization framing for this report. Throughout the report, there are times when the committee sought to emphasize the application of precision medicine approaches to maintenance of brain health (e.g., by continuously monitoring brain health and intervening prior to the development of disease) and in those contexts uses the term precision brain health. When referring to the application of precision medicine to specific preventive and therapeutic interventions, the committee uses the terms precision prevention and precision treatment, respectively.

- Research that has the potential to translate discoveries into a viable and diversified portfolio of interventions and biomarkers;

- Research that builds a foundation for precision medicine advances; and

- Research that maximizes the yields from existing research but also identifies opportunities to fill knowledge and data gaps.

Information Gathering

To complement its own expertise, the committee sought input from outside experts, advocates, and those with lived experience through a variety of mechanisms. The committee met and deliberated over a roughly 1-year period from October 2023 to November 2024. During this time, the committee held five public information-gathering sessions (October and November 2023, and January, April, and May 2024). During the October 2023 meeting, the committee received the charge from NIA and NINDS and clarified issues on the study’s scope. During its November meeting the committee hosted a short public session on approaches for increasing innovation in biomedical research. A public workshop held in conjunction with the January 2024 meeting included sessions with nonfederal funders of, and advocacy groups involved in, AD/ADRD research, AD/ADRD academic and industry researchers based in the United States and abroad, researchers from outside the AD/ADRD field employing tools and approaches that could be applied to AD/ADRD research, and a keynote from an individual with lived experience.

A brief public session was held during the committee’s fourth meeting to hear findings from and provide feedback to the author of a commissioned paper on sex and gender differences in AD/ADRD.19 A fifth public meeting was held in May 2024 during which researchers and clinicians explored research discoveries, identified considerations for research priorities, and discussed barriers that impede the advancement of research for related dementias. Public session agendas can be found in Appendix D. The committee meetings in April and July 2024 were held in closed session. To inform its deliberations, the committee used several mechanisms to gather information, including (1) the review of information submitted to the committee from NIA and others; (2) examination of publicly available information; (3) a commissioned paper on sex and gender differences in

___________________

19 The paper the committee commissioned on sex and gender differences in AD/ADRD addresses epidemiology, risk factors, clinical symptoms and diagnosis, clinical research, and treatment effects. While the committee’s report does not include an in-depth review of sex and gender differences related to each of these areas, a brief synopsis of the paper is provided in Box 1-3 and key information from the commissioned paper was incorporated in relevant sections throughout the report. The full paper is available at https://nap.edu/28588.

AD/ADRD that included keys gaps in research; and (4) reviews of the published literature, including a scoping review of published systematic reviews on interventions for preventing and treating AD/ADRD. Multiple literature reviews were conducted throughout this study using PubMed and Scopus to support the committee’s examination of the biomedical research landscape on AD/ADRD. These searches guided and provided references for content in this report. More information on the methods for the committee’s scoping review of recent systematic reviews can be found in Appendix A.

Report Organization

The committee structured its report around the following three key elements necessary to catalyze advances in AD/ADRD prevention and treatment:

- The ability to longitudinally track brain health and detect, diagnose, and monitor AD/ADRD development and progression (Chapter 2).

- Advancing understanding of disease pathways to guide effective strategies for AD/ADRD prevention and treatment (Chapter 3).

- The development and evaluation of interventions for prevention and treatment of AD/ADRD (Chapter 4).

The main report body concludes with a final chapter (Chapter 5) that summarizes the committee’s research priorities, highlights crosscutting issues from the previous chapters that impede progress in AD/ADRD prevention and treatment, and provides recommendations for overcoming these barriers. The research priorities identified by the committee are presented in order of the chapters, but cumulatively address the report’s goal of advancing the prevention and treatment of AD/ADRD. Of note, some key topics are inherently crosscutting and are therefore woven throughout the report chapters. These include equity, person centeredness, and opportunities to apply successful strategies for innovation from other fields.

REFERENCES

Adair, T., J. Temple, K. J. Anstey, and A. D. Lopez. 2022. Is the rise in reported dementia mortality real? Analysis of multiple-cause-of-death data for Australia and the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology 191(7):1270-1279.

Agora. 2024. Nominated target list. https://agora.adknowledgeportal.org/genes/nominated-targets (accessed August 22, 2024).

Akhter, F., A. Persaud, Y. Zaokari, Z. Zhao, and D. Zhu. 2021. Vascular dementia and underlying sex differences. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 13:720715.

AlzForum. 2022. CMS plans to limit Aduhelm coverage to clinical trials. https://www.alzforum.org/news/research-news/cms-plans-limit-aduhelm-coverage-clinical-trials (accessed August 13, 2024).

Alzheimer’s Association. 2021. What are frontotemporal disorders? Causes, symptoms, and treatment. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/frontotemporal-disorders/what-are-frontotemporal-disorders-causes-symptoms-and-treatment#typesandsymptoms (accessed August 13, 2024).

Alzheimer’s Association. 2023. 2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s and Dementia 19:1598-1695.

Alzheimer’s Association. 2024a. 2024 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures (accessed September 2, 2024).

Alzheimer’s Association. 2024b. What is Alzheimer’s disease? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers (accessed August 13, 2024).

Alzheimer’s Association. 2024c. Dementia with Lewy bodies. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia/types-of-dementia/dementia-with-lewy-bodies (accessed August 13, 2024).

Alzheimer’s Association. 2024d. Frontotemporal dementia. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia/types-of-dementia/frontotemporal-dementia (accessed August 13, 2024).

Alzheimer’s Association. 2024e. Aducanumab to be discontinued as an Alzheimer’s treatment. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/treatments/aducanumab (accessed August 13, 2024).

Andersen, K., L. J. Launer, M. E. Dewey, L. Letenneur, A. Ott, J. R. Copeland, J. F. Dartigues, P. Kragh-Sorensen, M. Baldereschi, C. Brayne, A. Lobo, J. M. Martinez-Lage, T. Stijnen, and A. Hofman. 1999. Gender differences in the incidence of AD and vascular dementia: The EURODEM studies. EURODEM Incidence Research Group. Neurology 53(9):1992-1997.

Arbanas, J., C. Damberg, M. Leng, N. Harawa, C. Sarkisian, B. Landon, and J. Mafi. 2023. Estimated annual spending on lecanemab and its ancillary costs in the US Medicare program. JAMA Internal Medicine 183(8):883-885.

Arenaza-Urquijo, E. M., R. Boyle, K. Casaletto, K. J. Anstey, C. Vila-Castelar, A. Colverson, E. Palpatzis, J. M. Eissman, T. Kheng Siang Ng, S. Raghavan, M. Akinci, J. M. J. Vonk, L. S. Machado, P. P. Zanwar, H. L. Shrestha, M. Wagner, S. Tamburin, H. R. Sohrabi, S. Loi, D. Bartrés-Faz, D. B. Dubal, P. Vemuri, O. Okonkwo, T. J. Hohman, M. Ewers, R. F. Buckley, Reserve, Resilience and Protective Factors Professional Interest Area, Sex and Gender Professional Interest area and the ADDRESS! Special Interest Group. 2024. Sex and gender differences in cognitive resilience to aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 20(8):5695-5719.

Artero, S., M. L. Ancelin, F. Portet, A. Dupuy, C. Berr, J. F. Dartigues, C. Tzourio, O. Rouaud, M. Poncet, F. Pasquier, S. Auriacombe, J. Touchon, and K. Ritchie. 2008. Risk profiles for mild cognitive impairment and progression to dementia are gender specific. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 79(9):979-984.

ASPE (Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation). Overview of the National Alzheimer’s Project Act Implementation. 2023. Presentation at the NAPA Advisory Council Meeting on October 30. https://aspe.hhs.gov/collaborations-committees-advisory-groups/napa/napa-advisory-council/napa-advisory-council-meetings/napa-past-meetings/napa-2023-meeting-material.

Barha, C. K., J. R. Best, C. Rosano, K. Yaffe, J. M. Catov, and T. Liu-Ambrose. 2020. Sex-specific relationship between long-term maintenance of physical activity and cognition in the Health ABC study: Potential role of hippocampal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume. Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 75(4):764-770.