Load Rating of Segmental Bridges (2024)

Chapter: 6 Execution of the Analytical Program

CHAPTER 6

Execution of the Analytical Program

6.1 Selection of the Set of Concrete Segmental Bridges

The objective of this task was to select a set of segmental bridges to be considered in this project. The selected set represents typical segmental bridges encountered in practice.

The team preselected eight DOTs from the following states to consult: Florida, Massachusetts, Texas, Colorado, California, Alabama, Michigan, and Minnesota. Based on the most recent (2023) data available from the NBI and InfoBridge, statistical analysis of segmental bridges was performed based on available bridge characteristics.

Selected bridge structures include those that are representative of location (chosen states), age, bridge maximum span length, total length, width, curvature, material type, rating method, and consequently, design live load model, traffic volume by ADTT, and condition.

These selection criteria were chosen based on the public domain data availability. Table 6-1 shows 50 preselected representative segmental bridge structures, where 41 bridges were selected from the chosen states, and nine bridges were selected based on the available bridge data from project partners. Of the nine bridges, one is in North Carolina and one is in Tennessee.

The broad spectrum of selected segmental bridges serves as a basis for developing new AASHTO rating procedures.

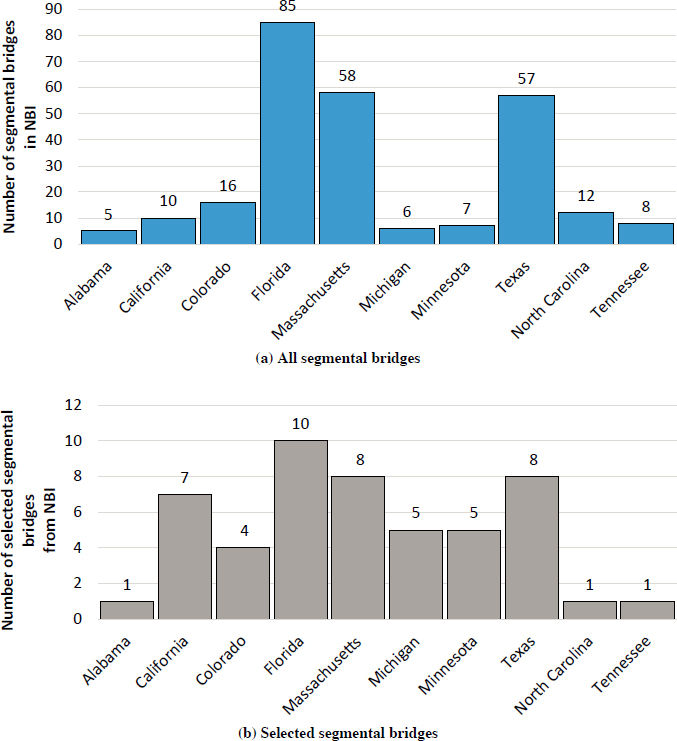

Statistical analysis of segmental bridges for preselected states was conducted. The filtering criteria for all segmental bridges in chosen states were compared to the selected sample data. Figure 6-1 presents the number of all segmental bridges for chosen states, and the number of selected segmental bridges for every state. The location of the selected segmental bridges is shown on the map (Figure 6-2).

The set of comparisons for all segmental bridges and selected segmental bridges is shown for bridge age, maximum span length, total length, number of approaching spans, number of lanes, ADTT per lane, superstructure condition rating, and operating rating method. Figure 6-3 presents the comparison of parameters along with the percentage of each group for the overall sample for selected and all segmental bridges.

6.2 Data Collection

In this step, the data required to conduct analyses of the selected bridges were collected. These data include information that reflects the current bridge condition (including inspection reports, field surveys, and relevant measurements), design and as-built plans, construction documents (contractor-proposed changes, shop drawings, casting and erection plans, material properties, casting records, construction loads, etc.), maintenance records (including repair and rehabilitation records), and rating reports (inventory and operating ratings).

Table 6-1. The 50 selected representative segmental bridges.

| State | Bridge ID | Year Built | Material | Max Span Length (ft) | Total Span Length (ft) | Number of Spans | Deck Width (ft) | Number of Lanes | Curvature (degree) | ADTT per Lane | Rating Method* | Superstructure Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 6156780 | 2019 | P/C Cont. | 165 | 6,549 | 42 | 71 | 6 | 0 | 3,454 | No Rating | Good |

| California | 06 0210 | 2016 | P/C Cont. | 591 | 1,942 | 5 | 104 | 5 | 0 | 2,520 | Assigned LRFR | Good |

| 10 0299 | 2009 | P/C Cont. | 571 | 1,355 | 3 | 43 | 2 | 0 | 11 | Assigned LFR | Fair | |

| 24C0546 | 2009 | P/C Cont. | 430 | 970 | 3 | 82 | 4 | 0 | 2,244 | Assigned LFR | Fair | |

| 28 0153R | 2007 | P/C | 659 | 7,434 | 16 | 82 | 5 | 0 | 249 | Assigned LFR | Good | |

| 35 0331L | 2009 | P/C | 443 | 972 | 3 | 29 | 1 | 0 | 336 | Assigned LFR | Good | |

| 35 0331R | 2009 | P/C | 448 | 904 | 3 | 29 | 1 | 0 | 73 | Assigned LFR | Good | |

| 57 1186 | 2007 | P/C | 297 | 3,320 | 12 | 76 | 4 | 0 | 73 | Assigned LFR | Good | |

| Colorado | F-08-AV | 1989 | P/C Cont. | 210 | 1,320 | 7 | 35 | 2 | 0 | 1,020 | LFR | Good |

| F-11-AM | 1977 | P/C Cont. | 225 | 748 | 4 | 42 | 2 | Variant Skewness | 1,071 | LFR | Fair | |

| F-11-AN | 1977 | P/C Cont. | 225 | 748 | 4 | 42 | 2 | 0 | 1,071 | Field Evaluation | Fair | |

| H-09-U | 2005 | P/C Cont. | 270 | 620 | 3 | 73 | 2 | 0 | 391 | LRFR | Fair | |

| Florida | 100806 | 2006 | P/C Cont. | 142 | 17,001 | 122 | 60 | 3 | 0 | 1,585 | LFR | Good |

| 150189 | 1986 | P/C Cont. | 1200 | 21,877 | 11 | 95 | 4 | 0 | 474 | LRFR | Good | |

| 170176 | 2003 | P/C Cont. | 300 | 3,097 | 11 | 106 | 4 | Variant Skewness | 723 | LFR | Good | |

| 570091 | 1993 | P/C Cont. | 225 | 19,265 | 141 | 43 | 2 | 0 | 268 | LRFR | Fair | |

| 580174 | 1999 | P/C Cont. | 225 | 18,425 | 131 | 43 | 2 | 0 | 595 | LRFR | Fair | |

| 720640 | 2005 | P/C Cont. | 248 | 2,570 | 13 | 43 | 1 | Variant Skewness | 875 | LRFR | Good | |

| 860631 | 2002 | P/C Cont. | 190 | 784 | 5 | 97 | 6 | 0 | 148 | LFR | Fair | |

| 890151 | 1997 | P/C Cont. | 260 | 4,487 | 21 | 61 | 3 | 0 | 408 | LFR | Good | |

| 900101 | 1982 | P/C Cont. | 135 | 35,868 | 266 | 39 | 2 | 0 | 474 | LRFR | Fair | |

| 900117 | 1981 | P/C Cont. | 118 | 4,557 | 39 | 39 | 2 | 0 | 2,170 | LRFR | Fair | |

| Massachusetts | B16600900 | 2003 | P/C Cont. | 143 | 547 | 4 | 54 | 3 | 0 | 1,118 | LFR | Fair |

| B166018YX | 2002 | P/C Cont. | 143 | 715 | 5 | 67 | 5 | 0 | 1,317 | LFR | Fair | |

| B166038DF | 2005 | P/C Cont. | 147 | 1,029 | 7 | 36 | 2 | 0 | 255 | LFR | Good | |

| B166118Y3 | 2001 | P/C Cont. | 163 | 697 | 5 | 29 | 1 | Variant Skewness | 1,874 | LFR | Fair | |

| B166569AJ | 2000 | P/C Cont. | 150 | 300 | 2 | 90 | 6 | 0 | 411 | LFR | Fair | |

| B166618QY | 2002 | P/C Cont. | 154 | 667 | 5 | 51 | 3 | 9 | 864 | LFR | Fair | |

| B166629Q3 | 2006 | P/C Cont. | 142 | 283 | 2 | 43 | 2 | 0 | 200 | AS | Fair | |

| B166818QV | 2002 | P/C | 105 | 111 | 1 | 60 | 4 | 4 | 1,072 | LFR | Fair |

| Michigan | 6717 | 1983 | P/C Cont. | 270 | 580 | 3 | 46 | 2 | 0 | 657 | LRFR | Good |

| 9168 | 1980 | P/C Cont. | 392 | 8,061 | 25 | 75 | 4 | 0 | 657 | LRFR | Fair | |

| 9169 | 1984 | P/C Cont. | 392 | 8,085 | 26 | 75 | 4 | 0 | 689 | LRFR | Fair | |

| 9170 | 1984 | P/C Cont. | 243 | 648 | 4 | 29 | 1 | 0 | 106 | LRFR | Fair | |

| 11148 | 1984 | P/C Cont. | 181 | 1,567 | 5 | 36 | 2 | 0 | 492 | LFR | Good | |

| Minnesota | 27409 | 2008 | P/C | 505 | 1,221 | 4 | 92 | 5 | 0 | 1,008 | LRFR | Good |

| 27410 | 2008 | P/C | 498 | 1,228 | 4 | 90 | 5 | 0 | 1,008 | LRFR | Good | |

| 82045 | 2017 | P/C Cont. | 600 | 5,079 | 6 | 98 | 4 | 0 | 359 | LRFR | Fair | |

| 85801 | 2016 | P/C | 508 | 2,593 | 4 | 45 | 2 | 0 | 718 | LRFR | Good | |

| 85802 | 2015 | P/C | 180 | 2,593 | 4 | 37 | 2 | 0 | - | LRFR | Good | |

| North Carolina | 5140182P | 1983 | P/C Cont. | 508 | 1,249 | 8 | 45 | 2 | 0 | 718 | LRFR | Good |

| Tennessee | 5460214P | 2013 | P/C Cont. | 180 | 790 | 5 | 38 | 2 | 0 | 340 | AS | Good |

| Texas | 1.2102E+14 | 1980 | P/C Cont. | 750 | 10,538 | 1 | 60 | 4 | 0 | 1,144 | Assigned LFR | Fair |

| 1.4027E+14 | 2012 | P/C Cont. | 410 | 958 | 1 | 47 | 2 | 0 | 296 | Assigned LRFR | Good | |

| 1.4227E+14 | 1998 | P/C | 134 | 4,108 | 34 | 58 | 2 | 0 | 658 | Assigned LFR | Fair | |

| 1.4227E+14 | 1998 | P/C Cont. | 178 | 1,943 | 15 | 28 | 1 | 0 | 1,902 | Assigned LFR | Fair | |

| 1.5015E+14 | 1991 | P/C Cont. | 101 | 281 | 3 | 26 | 1 | 0 | 304 | No Rating | Good | |

| 1.5015E+14 | 1993 | P/C Cont. | 106 | 1,345 | 14 | 74 | 5 | Variant Skewness | 512 | No Rating | Fair | |

| 1.6178E+14 | 1973 | P/C Cont. | 200 | 3,280 | 1 | 56 | 4 | 0 | 676 | Field Evaluation | Fair | |

| 2.0181E+14 | 2015 | P/C | 320 | 3,896 | 3 | 70 | 3 | 0 | 1,469 | No Rating | Good |

*LFR: Load Factor Rating; AS: Allowable Stress; LRFR: Load and Resistance Factor Rating; Assigned LFR: Assigned Load Factor Rating for HS 20; Assigned LRFR: Assigned Load and Resistance Factor Rating for HL-93.

A DOT survey was conducted to gather essential data for performing the reliability-based analysis of segmental bridges. An important part of data collection is the identification of construction methods (balanced cantilever, span-by-span, etc.) and information about erection procedures (such as cantilever alignment and segment age when erected). Table 6-2 presents the data request, which was sent to DOTs for the 50 selected segmental bridges.

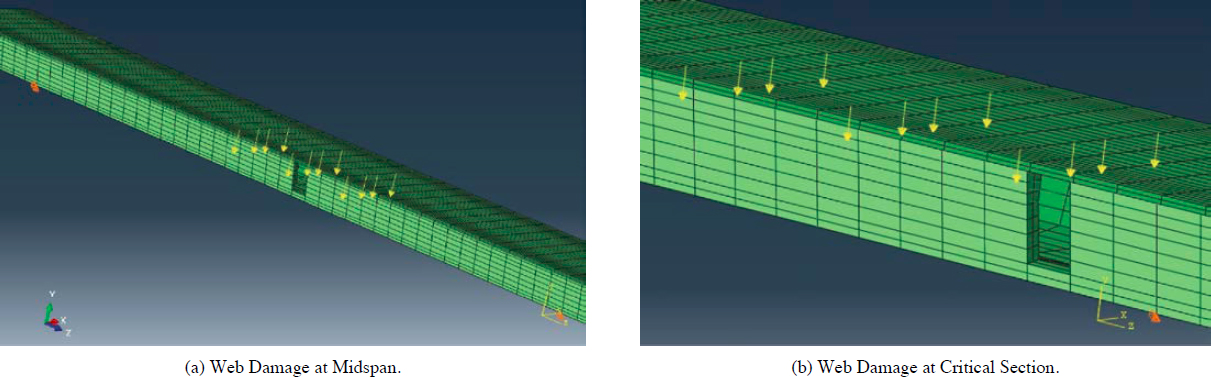

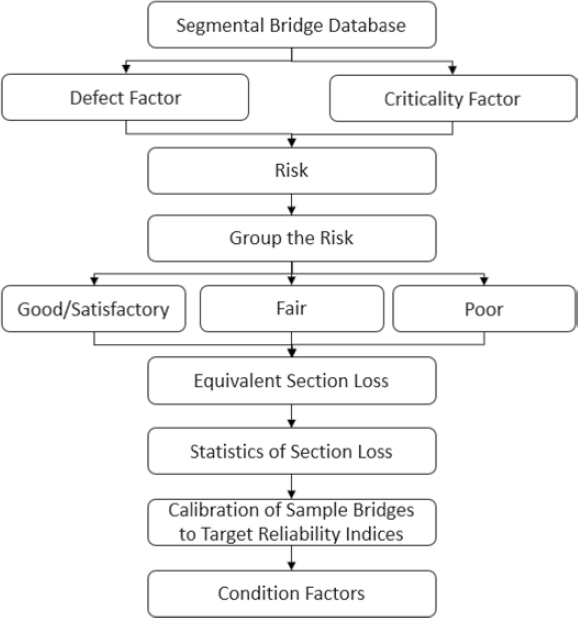

The team also collected information on as-inspected deterioration data and the effect on load rating from examples available from the team’s industrial partners. To incorporate the bridge deterioration into the load rating analysis, the team performed the following steps:

- Collect bridge deterioration information and data; inspection reports going back multiple cycles were requested from various participating states.

- Categorize the major/dominant deterioration modes on segmental concrete bridges (e.g., section loss of post-tensioned reinforcement) based on field data and expert opinions.

- Evaluate how the deterioration modes impact the bridge load rating in terms of specific structural components and limit states.

- Summarize the findings and possible ways of incorporating deterioration into a detailed load rating analysis.

In addition to the bridge condition ratings from inspections, two types of condition ratings data are available, including NBI component ratings and AASHTO element ratings. The team collected data and investigated whether and how to use these data in the load rating analysis.

Four state DOTs provided the data on the segmental bridges as shown in Table 6-3.

6.3 Selection of Limit States

Based on a review of the rating information and preliminary analysis of the structures identified in Section 6.1, as well as input from segmental bridge experts, including those on the research team and ASBI and state transportation agencies, appropriate limit states were identified for service and strength levels. The following five limiting criteria were considered:

- Service limit state

- Flexural tensile stress

- Flexural compressive stress

- Principal tensile stress (combined flexural, shear, and torsional effects)

- Strength limit state

- Flexural strength

- Shear strength (from combined direct shear and torsion)

Table 6-2. DOT data collection for segmental bridges.

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Bridge Inspection Report | Most recent and historical bridge inspection reports for selected bridges (Table 6-1). |

| Field Surveys | Performed detailed bridge surveys. |

| Field Measurements | Bridge field testing for bridge evaluation or other reasons. |

| Design Plans | Detailed drawings including cross-section properties, with an indication of variable/constant depth, internal and external tendons, etc. |

| As-Built Plans | Post-construction drawings. |

| Construction Shop Drawings | Construction drawings, including balanced cantilever, span-by-span, etc. |

| Casting and Erection Plans | Erection scheme and plan procedures, such as cantilever alignment and segment age when erected. |

| Material Properties | Material properties and testing data. |

| Casting Records | - |

| Construction Loads | - |

| Maintenance Records (including repair and rehabilitation) | Any maintenance activities and their descriptions. |

| Segmental Bridge Deterioration | Major deterioration modes on segmental concrete bridges. |

| Rating Reports: Inventory and Operating Rating Calculations | Rating reports, including calculation of section capacities for all limit states, transverse, and longitudinal analysis results. |

| Rating Cards | Summary of the calculated ratings and safe live load-carrying capacities. |

| NBI Component Ratings | NBI component rating description. |

| AASHTO Element Ratings | AASHTO component rating description. |

| Rating issues | Describe any segmental bridge rating issues. |

| Long-term monitoring data | Long-term monitoring data if available. |

| Creep and Shrinkage Models | Creep and shrinkage models selected during design. |

Table 6-3. Segmental bridge data collected from state DOTs.

| State | No. of Bridges | Types of Data |

|---|---|---|

| California | 14 | Bridge inspection reports, design plans. |

| Colorado | 16 | Inspection sketches, photographs, design plans, load rating information. |

| Massachusetts | 57 | Bridge inspection reports, design plans load rating reports. |

| Michigan | 2 | Design plans, load rating reports. |

Consideration must be given to joint behavior. Thus, in the longitudinal direction, these limit states were at each joint. Similar checks were conducted in the transverse direction.

The service limit states are consistent with the previous service limit state calibration work conducted under NCHRP Project 12-83. The team identified the stress limits at service limit state for longitudinal and transverse analysis as shown in Table 6-4 [based on FDOT’s New Directions for Florida Post-Tensioned Bridges (Corven Engineering 2004)].

Table 6-4. Stress limits in concrete at the inventory and operating ratings for segmental bridges.

| At the Service Limit State After Losses | Stress Limit Inventory Rating | Stress Limit Operating Rating | Source of Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

Compression (Longitudinal or Transverse)

|

LRFD Table 5.9.2.3.2a-1 LRFD Article 5.6.4.7.2c |

||

Longitudinal Tensile Stress in Precompressed Tensile Zone (intended for segmental and similar construction)

|

0.3 ksi tension | ksi tension | LRFD Table 5.9.2.3.2b-1 and FDOT no distinction for environment |

|

No tension |

No tension |

LRFD Table 5.9.2.3.2b-1 |

Longitudinal Tensile Stress through Joints in Precompressed Tensile Zone (intended for segmental and similar construction)

|

0.3 ksi tension | ksi tension | LRFD Table 5.9.2.3.2b-1 Seg. Guide Spec. 9.2.2.2 FDOT has no distinction for environment |

|

No tension |

No tension |

Ditto and FDOT Seg. Rating Criteria |

|

0.1 ksi min comp. | No tension | Seg. Guide Spec. 9.2.2.2 FDOT Seg. Rating Criteria |

Transverse Tension, Bonded PT

|

0.3 ksi tension |

ksi tension |

Seg. Guide Spec. 9.2.2.3 LRFD Table 5.9.2.3.2b-1 FDOT has no distinction for environment FDOT Seg. Rating Criteria |

| At the Service Limit State After Losses | Stress Limit Inventory Rating | Stress Limit Operating Rating | Source of Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

Tensile Stress in Other Areas

|

Seg. Guide Spec. 9.2.2.4 |

||

|

ksi tension |

ksi tension |

LRFD Table 5.9.2.3.2b-1 Seg. Guide Spec. 9.2.2.4 LRFD Table 5.9.2.3.2b-1 |

Principal Tensile Stress at Centroidal Axis in Webs (Service III)

|

ksi tension |

ksi tension |

LRFD 5.9.2.3.3 FDOT LRFR Rating Criteria |

|

* Principal tensile stress is calculated for longitudinal stress and maximum shear stress due to shear or combination of shear and torsion, whichever is greater. For segmental box, check centroidal axis. For composite beam, check at centroidal axis of beam only and at centroidal axis of composite section, and take the minimum value. Web width is measured perpendicular to the place of web. For segmental box, it is not necessary to consider coexistent web flexure.

Account should be taken of vertical compressive stress from vertical PT bars provided in the web, if any, but not including vertical component of longitudinal draped post-tensioning. The latter should be deducted from shear force due to applied loads. Check section at H/2 from edge of bearing or face of diaphragm, or at end of anchor block transition, whichever is more critical. For the design of a new bridge, a temporary principal tensile stress of kis may be allowed during construction, per AASHTO Seg. Guide Spec. Initial load ratings for new design should be based upon specified concrete strength. Load rating of an existing bridge should be based on actual concrete strength from construction or subsequent test data. |

|||

6.4 Comparative Analysis That Includes Comparison with Field Data

6.4.1 Introduction

A comparative analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of several factors on the load rating of concrete segmental bridges in the longitudinal direction. This comparative analysis was conducted to aid the engineer in understanding the impact that certain assumptions have on the load rating of concrete segmental bridges. The investigated factors and parameters included the following:

- Influence of the selection of creep and shrinkage models on load rating.

- Influence of temperature gradient compared to other load cases on load rating.

- Influence of compressive strength overstrength factors on load rating.

- Influence of the selection of time-dependent concrete strength development model on load rating.

- Influence of various load cases on principal tensile stress in the web and impact of assumed allowable tensile stress on load rating.

- Influence of condition factors on load rating.

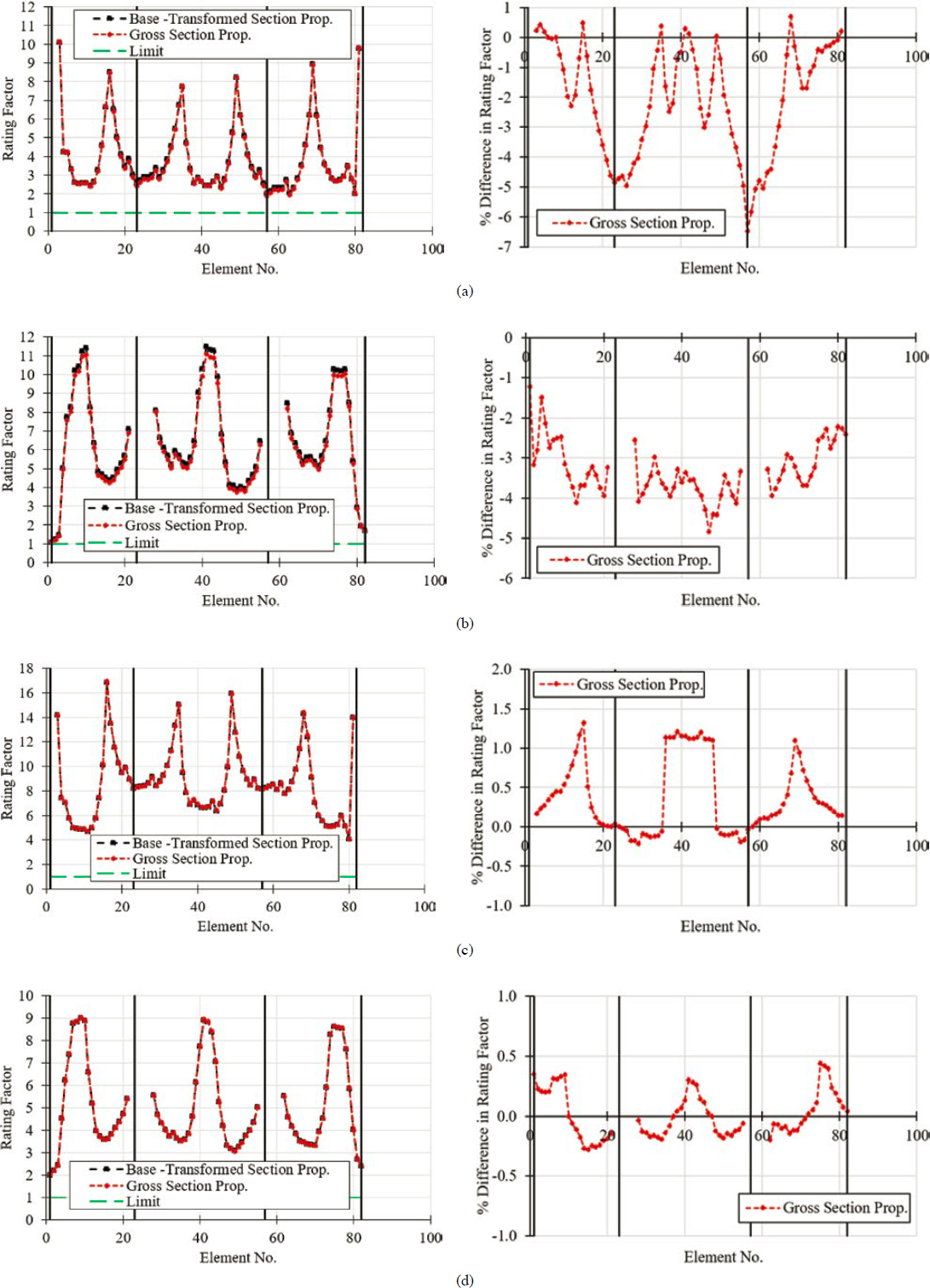

- Influence of the use of transformed versus gross-section properties on load rating.

- Influence of time when the load rating is conducted on load rating factors.

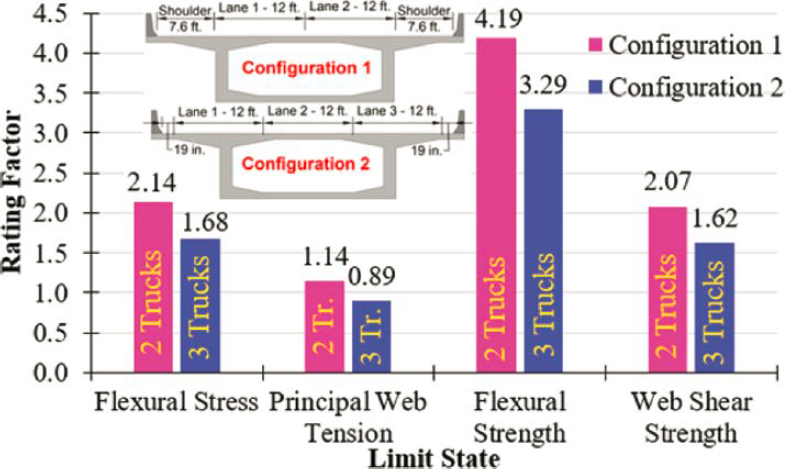

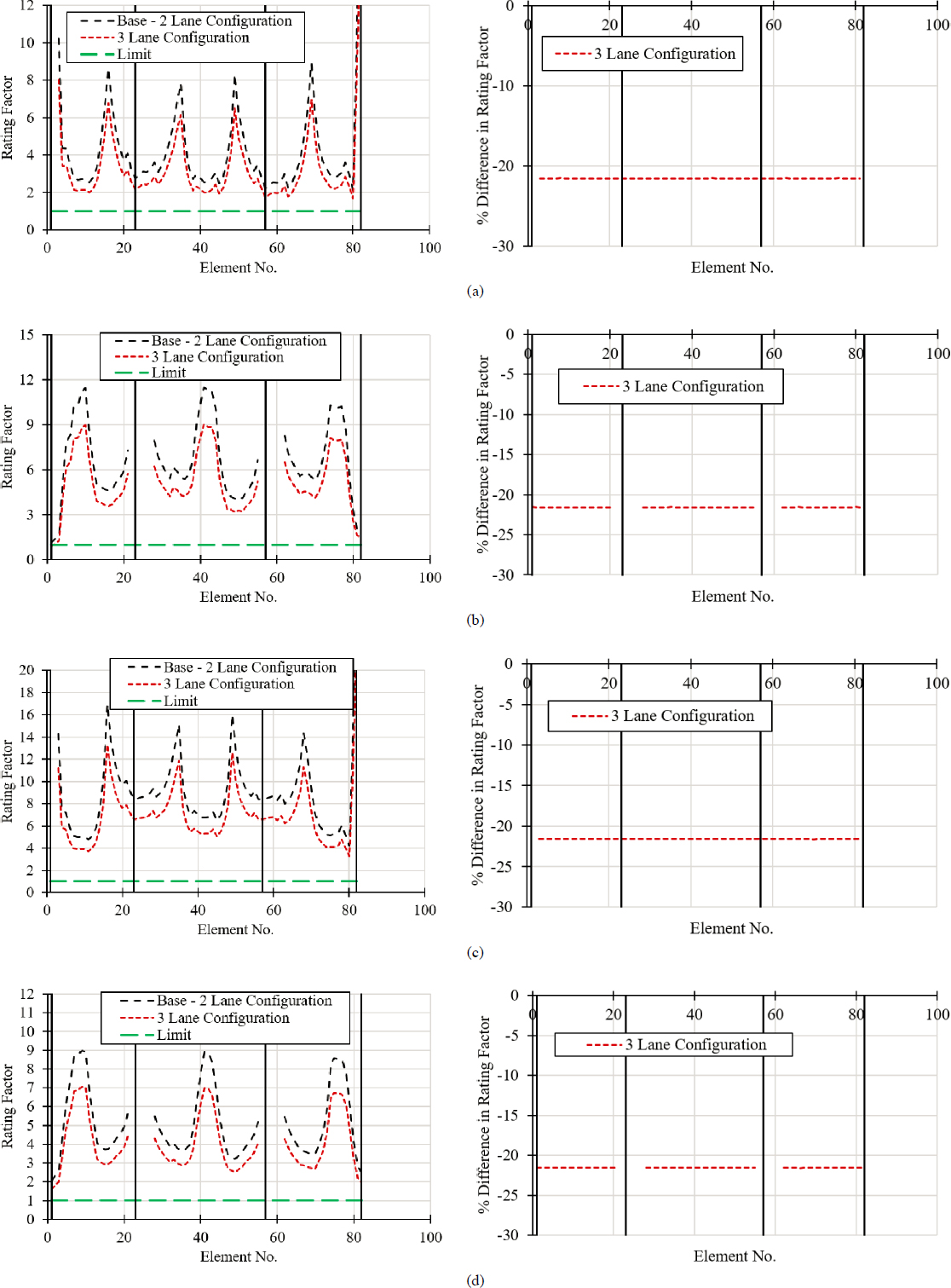

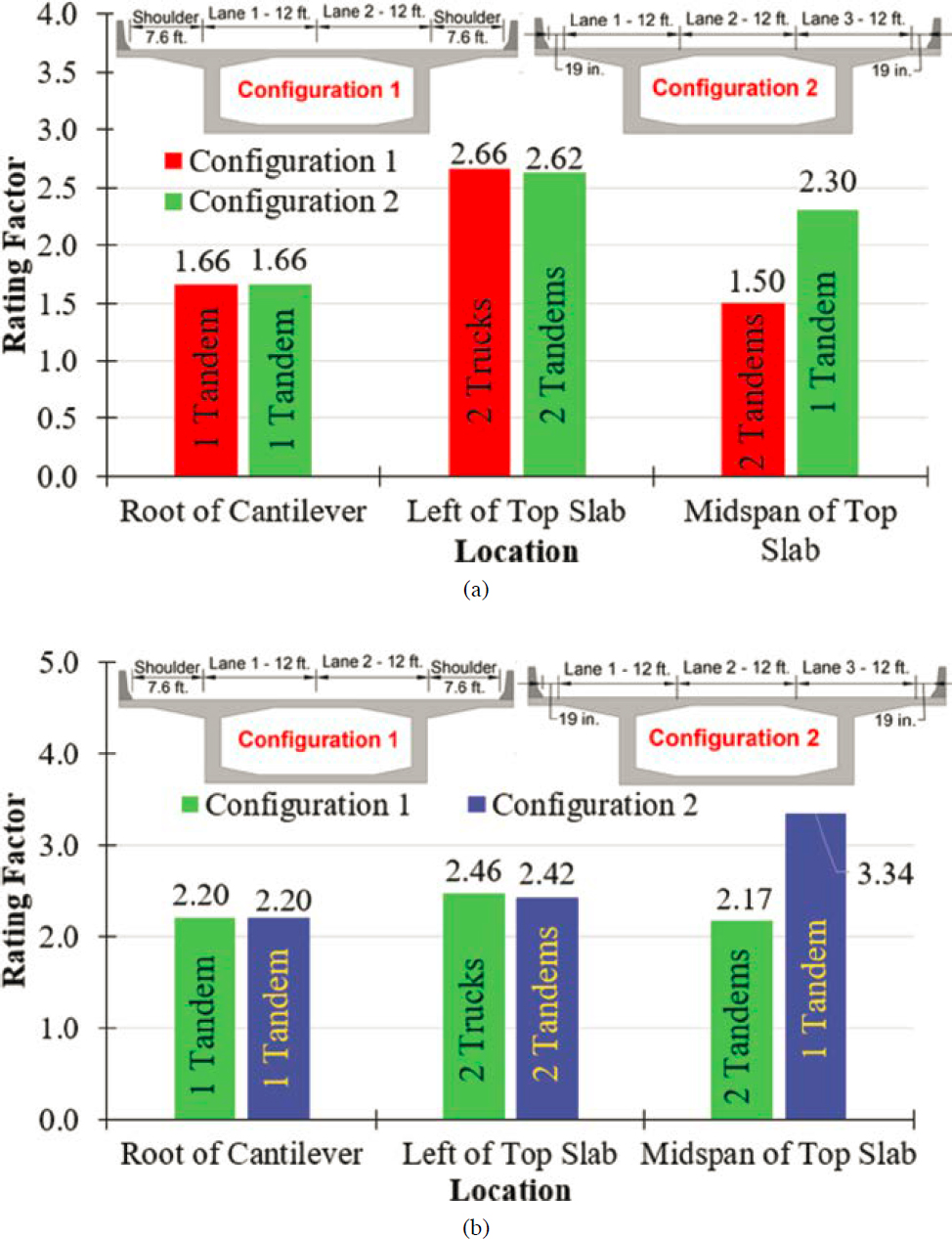

- Influence of multiple trucks on load rating.

While a total of four load rating examples are presented for bridges constructed with (1) the span-by-span method, (2) balanced cantilever method, (3) incremental launching method, and (4) a cable-stayed bridge, the comparative analysis was conducted for the bridges constructed

Table 6-5. Outline of load rating analysis.

| Analysis Level | Analysis Direction | Load Combinations | Limit States |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inventory | Longitudinal | Service I/III | Flexure (compression and tension) |

| Principal Web Tension (flexure, shear, and torsion) | |||

| Strength I | Flexural Strength | ||

| Shear Strength (considering torsional effects) | |||

| Transverse | Service I | Top Slab Flexure | |

| Strength I | Top Slab Flexural Strength |

with the span-by-span and balanced cantilever method. The influence of (1) time when the load rating is conducted, (2) the use of transformed versus gross-section properties, and (3) multiple trucks on load rating was conducted only for the concrete segmental bridge constructed with the balanced cantilever method. The bridges used to prepare the load rating examples represent simplified versions of real bridges (Midas Civil 2023). All bridges feature internally bonded tendons. The load rating examples (Appendix C of the Guideline) provide detailed information about the load rating of the abovementioned four bridges. Section C.1 in the load rating examples presents detailed information about the assumptions made during the analysis. A summary of key points is repeated here for convenience. All bridges considered were load rated at the inventory level considering Service I/III and Strength I load combinations. The outline of the analysis as well as the considered limit states are presented in Table 6-5 and the load factors used for each load combination are presented in Table 6-6. The strength reduction factors were based on AASHTO LRFD (2020a). Condition factors and system factors were based on AASHTO MBE (2020b). Multiple presence factors (MPFs) were based on AASHTO LRFD (2020a). Flexural strength was based on AASHTO LRFD (2020a) provisions for prestressed concrete cross sections with internally bonded tendons. Although Corven Engineering (2004) recommends the use of actual material properties when calculating flexural strength, specified material properties were used because this information was not available for the bridges considered. Shear strength was based on AASHTO LRFD (2020a) alternative shear provisions for concrete segmental bridges. The combination of torsional and shear effects at service and at ultimate limit state was based on AASHTO LRFD (2020a). Allowable stresses in concrete segments for load rating were based on the recommendations provided by Corven Engineering (2004).

Table 6-6. Load factors and combinations for the design load rating at the inventory level for HL-93.

| Analysis | LRFD Permanent Load | LRFD Transient Loads | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γDC | γDW | γEL | γPS | γCR,SH | γFR | γTU | γTG | γLL | ||

| Long. | Strength I | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.75 |

| Service I/III | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.80 | |

| Trans. | Strength I | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.75 |

| Service I | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.80 | |

| γDC: load factor for structural components; γDW: load factor for permanent superimposed dead loads; γEL: load factor for locked-in construction stresses; γPS: load factor for prestressing effect; γFR: load factor for bearing friction or frame action; γCR,SH: load factor creep and shrinkage; γTU: load factor for uniform temperature load; γTG: load factor for thermal (temperature) gradient; and γLL: load factor for live load. | ||||||||||

The load rating factors (RFs) were calculated using Eqs. (6-1 through 6-4).

| (6-1) |

For the strength limit states:

| (6-2) |

| (6-3) |

For the service limit states:

| (6-4) |

where

| DC = | dead load of structural components and nonstructural attachments. |

| DW = | dead load of wearing surfaces and utilities. |

| PS = | secondary forces from post-tensioning for strength limit states; total prestress forces for service limit states. |

| EL = | miscellaneous locked-in force effects resulting from the construction process, including jacking apart of cantilevers in segmental construction. |

| FR = | friction load. |

| TU = | force effect due to uniform temperature. |

| CR = | force effects due to creep. |

| SH = | force effects due to shrinkage. |

| TG = | force effect due to temperature gradient. |

| LL = | vehicular live load. |

| IM = | vehicular dynamic load allowance. |

| γDC = | load factor for structural components. |

| γDW = | load factor for permanent superimposed dead loads. |

| γEL = | load factor for secondary post-tensioning effects and locked-in erection loads. |

| γFR = | load factor for bearing friction or frame action. |

| γCR,SH = | load factor for creep and shrinkage. |

| γTU = | load factor for uniform temperature. |

| γTG = | load factor for temperature gradient. |

| γLL = | load factor for live load. |

| C = | capacity. |

| ϕc = | condition factor. |

| ϕs = | system factor. |

| ϕ = | resistance factor per LRFD. |

| Rn = | nominal member resistance as inspected, measured, and calculated according to formulas in LRFD. |

Unless otherwise noted, the baseline or benchmark case used in the comparative analysis included the following options:

- CEB-FIP (1990) model was used for predicting creep and shrinkage behavior, and concrete compressive strength development with time.

- AASHTO LRFD (2020a) model was considered for the calculation of modulus of elasticity of concrete at 28 days.

- No overstrength factors were used (i.e., specified concrete compressive values were considered).

- Transformed-section properties were used.

- Load rating was conducted at 10,000 days after the completion of the bridge.

- The structure was assumed to be subject to a ± 70 °F uniform temperature change.

- The temperature gradient effects were based on AASHTO LRFD (2020a) solar radiation zone 3.

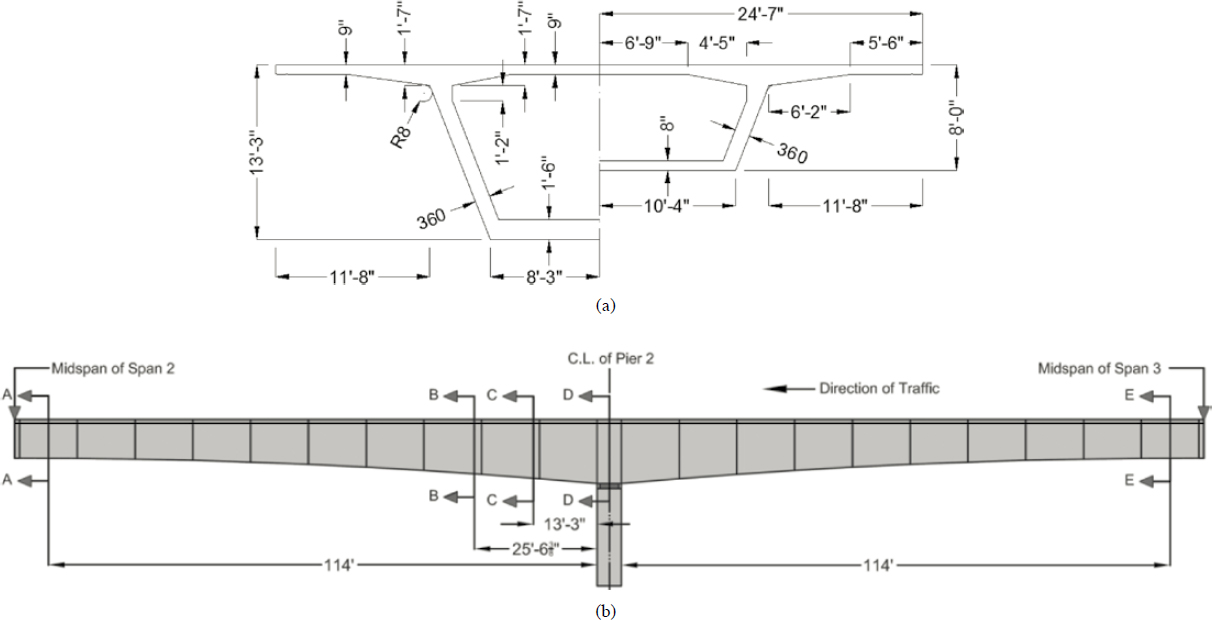

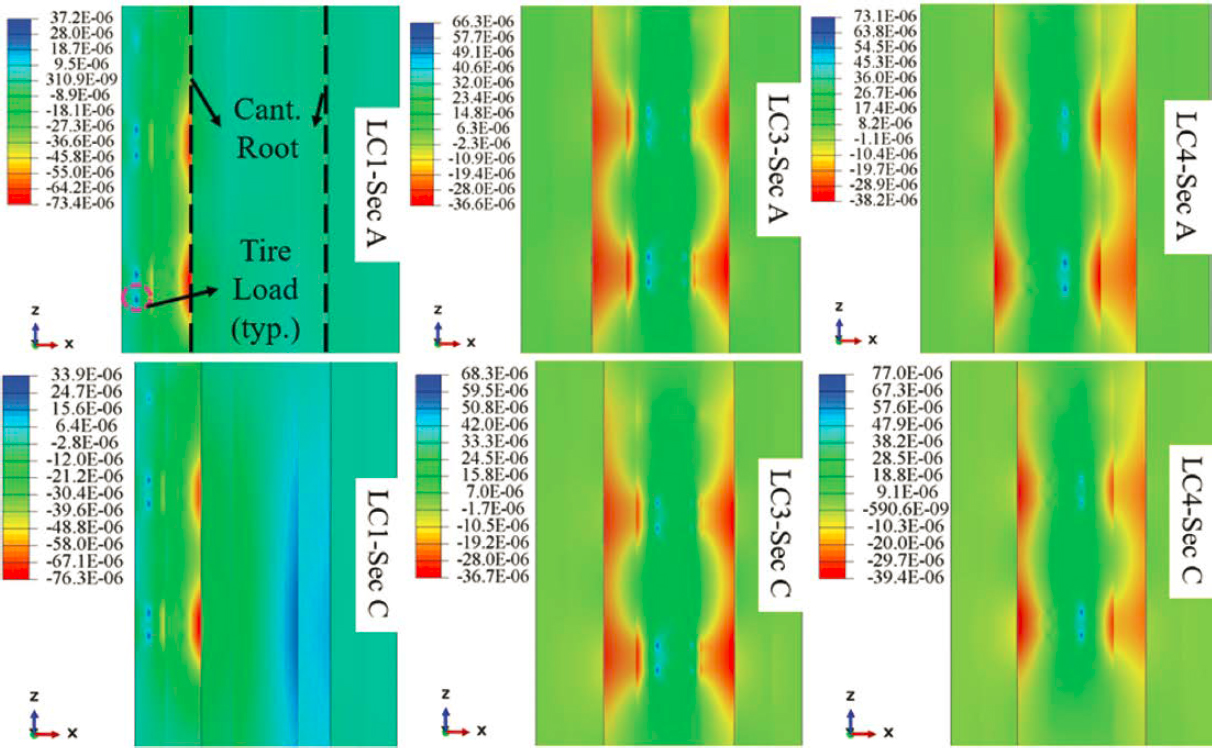

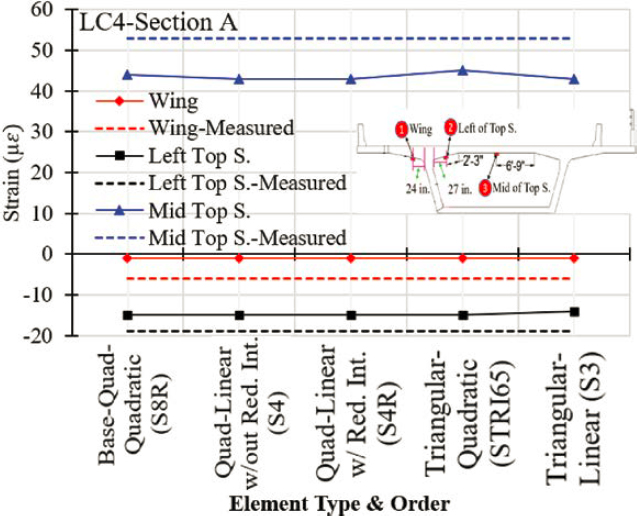

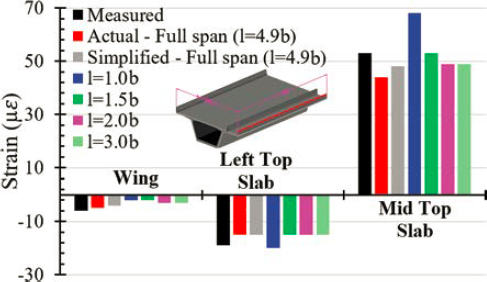

A comparative analysis was also conducted in the transverse direction and included a comparison of live load effects obtained using Homberg charts and a 2D frame model, a 3D shell FE model, and field data for the Seabreeze Bridge located in Daytona, Florida.

A general discussion of several of the considered factors is presented. The quantification of the influence of each factor is provided in the subsequent sections.

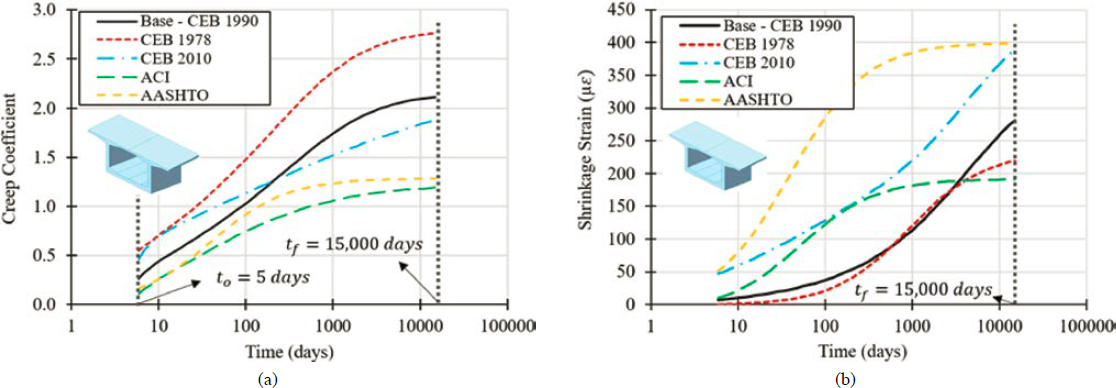

6.4.1.1 Creep and Shrinkage

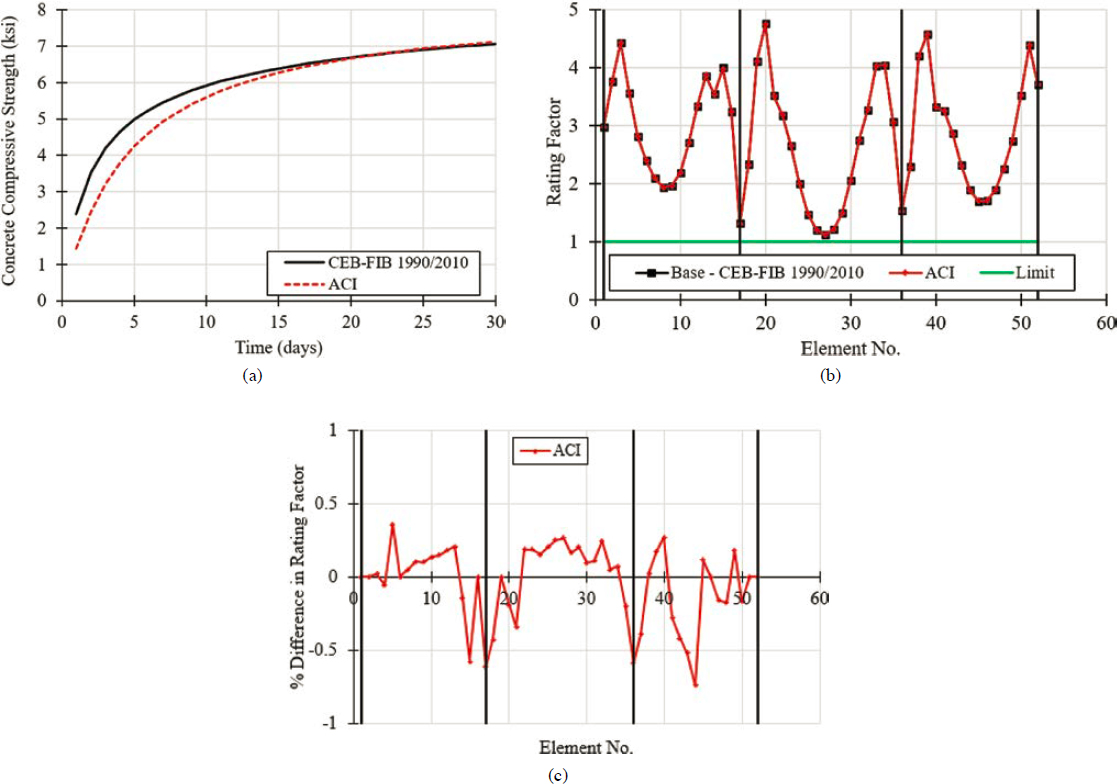

Currently, AASHTO LRFD (2020a) Article 5.4.2.3.1 states that where mix-specific data are not available, estimates of shrinkage and creep may be made using the provisions of any of the following: (1) the creep and shrinkage models in AASHTO LRFD (2020a) Articles 5.4.4.3.2 and 5.4.4.3.3; (2) the fib Model Code for Concrete Structures (fib 2010); (3) the CEB/FIP Model Code for Concrete Structures (CEB-FIP 1990), or ACI 209. In addition, it is stated that for concrete segmental bridges, a more precise estimate shall be made, including the effect of all the following: (1) specific materials, (2) structural dimensions, (3) site conditions, (4) construction methods, and (5) concrete age at various stages of erection. It should be noted that ACI Committee 209 presents four models in the appendix of ACI 209.2R-08 namely: (1) ACI 209R-92 model, (2) Bažant-Baweja B3 model, (3) CEB MC90-99 model, and (4) GL2000 model [developed by Gardner and Lockman (2000)]. This leaves the engineer with a plethora of options when it comes to the selection of creep and shrinkage models for load rating concrete segmental bridges. The impact that the selection of creep and shrinkage models has on load rating is reflected in (1) the computation of prestress losses, and (2) the computation of secondary forces created due to the statical indeterminacy of the bridge as well as those created due to force redistribution due to creep effects. The impact that the selection of a particular creep and shrinkage model has on load rating was investigated for a bridge constructed with the span-by-span and another constructed with the balanced cantilever method. The following creep and shrinkage models were considered: (1) CEB-FIP 1990, (2) fib 2010, (3) CEB-FIP 1978, (4) AASHTO LRFD (2020a), and ACI 209R-92. The inclusion of CEB-FIP 1978 was done to evaluate the influence of creep and shrinkage models that were used extensively by the concrete segmental bridge community in the past on the load rating of concrete segmental bridges. When it comes to the evaluation of various creep and shrinkage models, it should be noted that there is no agreement as to which statistical indicator(s) should be used, which data sets should be used, or what input data should be considered [ACI Committee 209 (2008)].

6.4.1.2 Influence of Temperature Gradient on Load Rating

The influence of positive and negative temperature gradients on the load rating of concrete segmental bridges was investigated by considering the two bridges mentioned previously. Stresses created by temperature gradients were compared with those created by other load cases. Temperature gradients for various solar radiation zones were considered to illustrate the impact that the geographic position of the bridge or other research-based temperature gradients that differ from those presented in AASHTO LRFD (2020a) had on load rating.

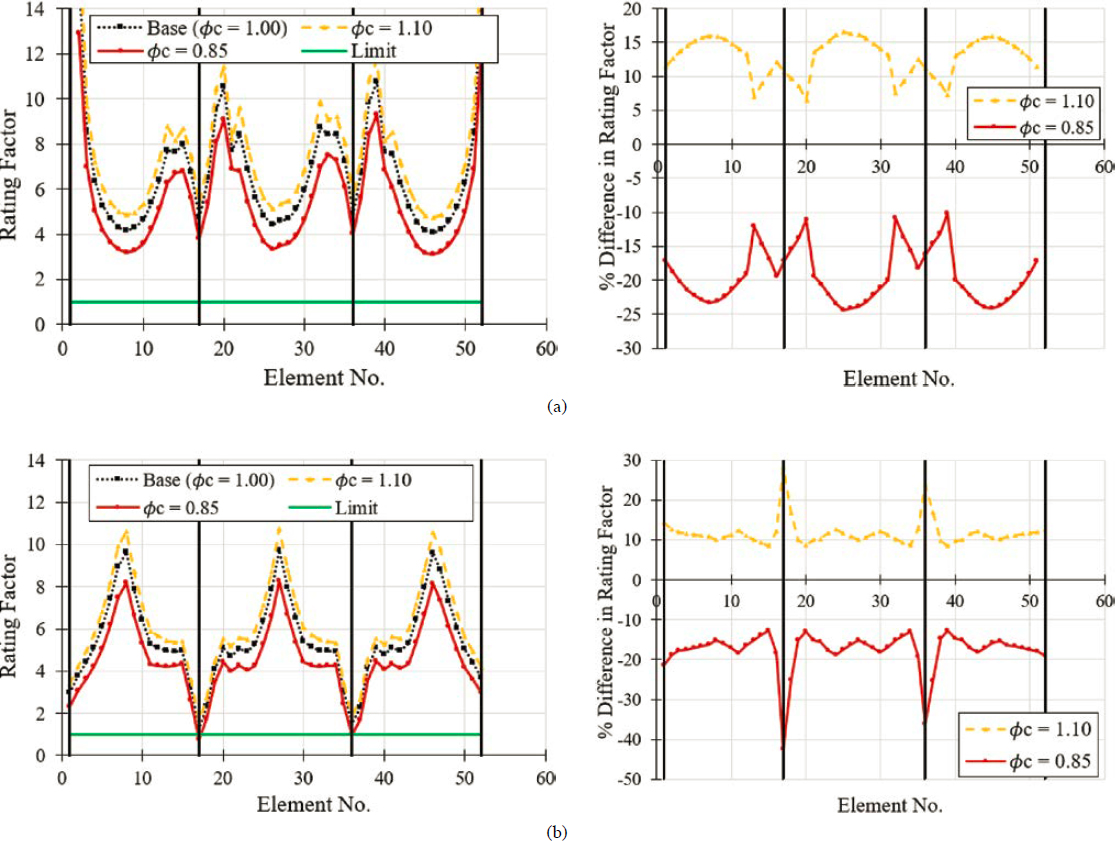

6.4.1.3 Compressive Strength Overstrength Factors

Compressive strength overstrength factors are herein defined as the ratio of expected to specified concrete compressive strength. The use of expected rather than specified concrete compressive strength resulted in higher rating factors through two mechanisms: (1) an increase in the allowable stresses, which are typically expressed as a function of concrete compressive strength, and (2) the impact that the use of a stronger concrete has on the time-dependent structural analysis. Both these aspects were investigated. A total of four overstrength factors were considered: 1.0, 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3. The overstrength factors were applied to the specified concrete compressive strength at 28 days.

6.4.1.4 Models for Predicting Concrete Compressive Strength Development over Time

Since the compressive strength of concrete varies with time, the influence of the selected model for predicting this variation on load rating was investigated. The models considered for predicting the variation of concrete compressive strength with time were (1) ACI 209R-92 (ACI 1992), and (2) fib (2010). The variation of compressive strength with time affects the variation of modulus of elasticity with time, which is predicted using functions expressed in terms of the compressive strength. The time-dependent modulus of elasticity is, on the other hand, used to determine time-dependent transformed-section properties, and the effective modulus is used to account for creep effects.

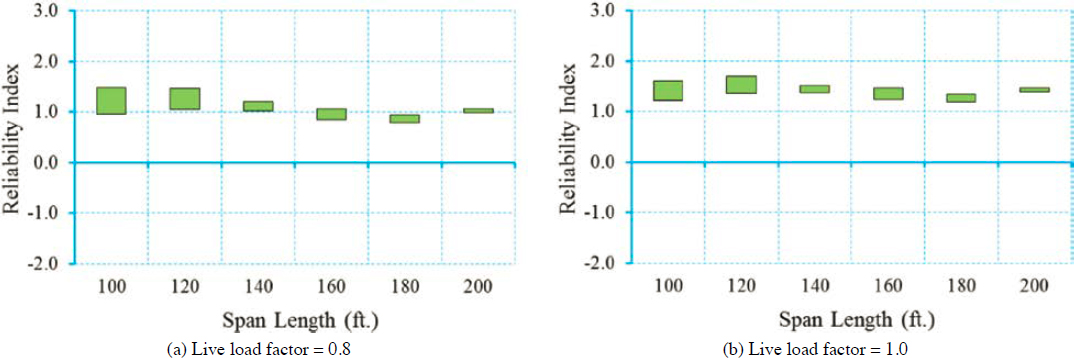

6.4.1.5 Influence of Various Load Cases on Principal Tensile Stress in the Web and Impact of Assumed Allowable Tensile Stress

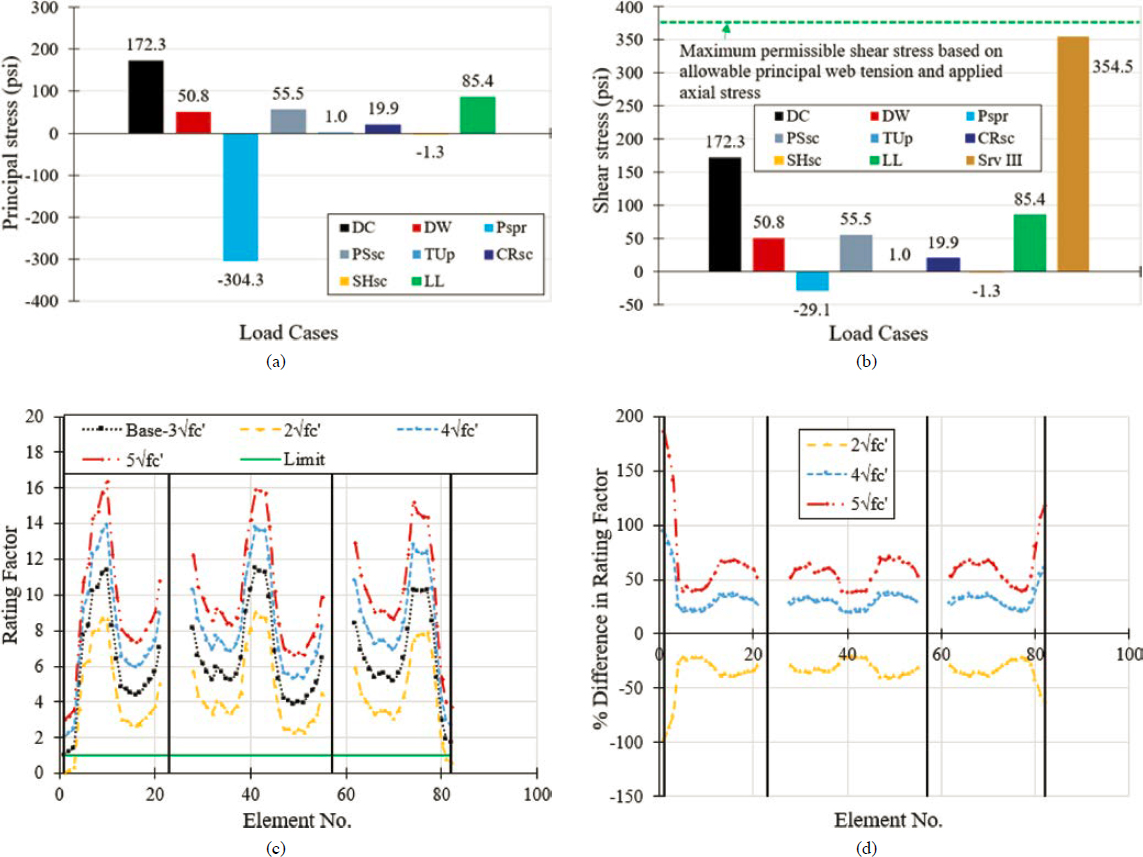

Since the load rating of concrete segmental bridges is controlled primarily by the service limit state, the impact that the selected allowable tensile stress has on load rating was investigated by considering various allowable tensile stress values for the principal tensile stress in the web. The considered allowable tensile stresses included (1) Zero tension, (2) ksi, (3) ksi, (4) ksi, and (5) ksi. In addition, the contribution of each load case to the principal tensile stress in the web was quantified. The guidance on selecting a value for the allowable principal tensile stress varies in terms of design and load rating. AASHTO LRFD (2020a) specifies a value of ksi and indicates that a factor of 0.8 should be used for live load (Service III). Corven Engineering (2004) recommends a value of ksi and a live load factor of 0.8 (Service III) for inventory rating.

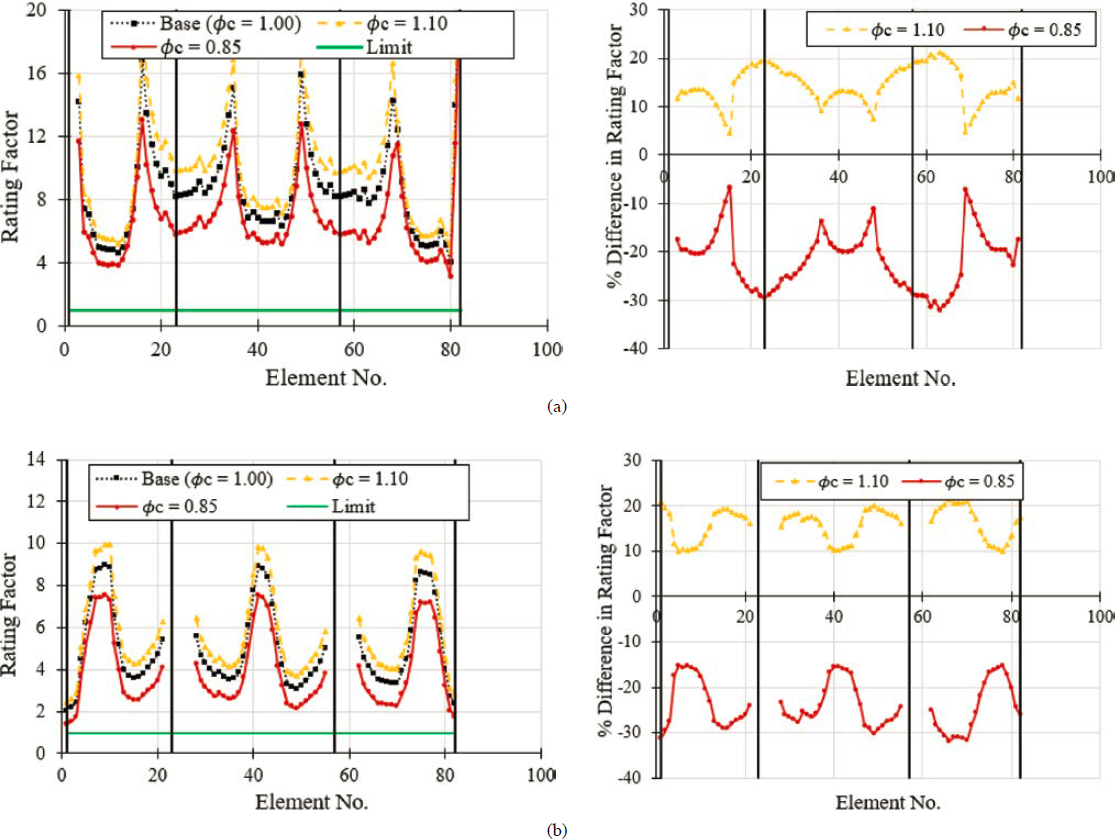

6.4.1.6 Influence of Condition Factors on Load Rating

Currently, condition factors are used as a metric to characterize deterioration. In the current formulation, condition factors affect the strength limit states (flexural and shear strength). The report by Corven Engineering (2004) provides guidance for how to determine condition factors for concrete segmental bridges. The recommendations were developed by extending the concepts of “structural condition” given in LRFR to the particulars of concrete segmental bridges.

The selection of condition factors for each limit state should be conducted such that it reflects the current condition of the bridge and with consideration for how that condition affects the limit state of interest. For example, Corven Engineering (2004) reports that if corrosion damage to bonded tendons is localized to one region or to one or more particular cross sections and the rest of the structure is otherwise satisfactory, then the low value (0.85) may be applied to those areas and an appropriately higher value to others. However, caution is advised since damage to an internal tendon at one section may mean that it may be partially effective at other sections.

The influence of condition factors on load rating was quantified by assuming different values for the condition factor and by load rating the bridge based on these assumptions.

6.4.1.7 Transformed versus Gross-Section Properties

The sequential nature of construction in concrete segmental bridges includes forces that are applied to the net concrete cross section, such as when post-tensioning is applied, and forces that are applied to the transformed concrete cross section, such as those created by loads applied after the grouting process in the ducts is completed for bridges that feature internally bonded tendons. The impact of the selection of gross- versus transformed-section properties was investigated by conducting load rating computations for each case. The use of transformed versus gross-section properties is typically left to the discretion of the engineer. Maguire et al. (2015) used uncracked, transformed-section properties, including tendons, mild reinforcement, barrier rails, and full flange width for their beamline elements in their beamline longitudinal model. In this investigation, the presence of barrier rails was ignored in the definition of the cross section and the calculation of the section properties. Transformed-section properties included the presence of tendons, whereas gross-section properties were based solely on the concrete segmental cross section.

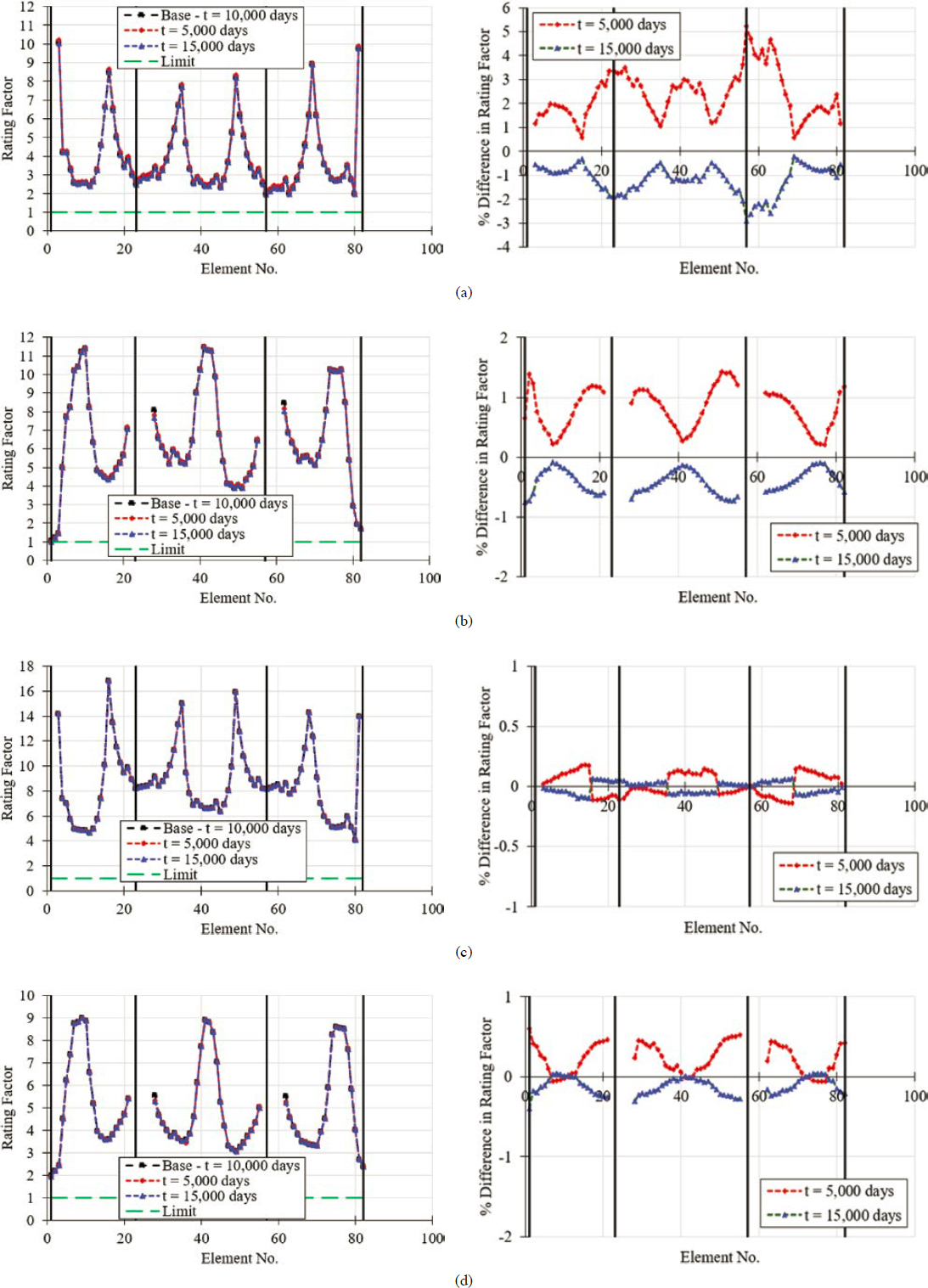

6.4.1.8 When the Load Rating Was Conducted

To quantify the impact that the time the bridge was rated has on the outcome of the rating, three cases were considered in terms of when the bridge was load rated. The baseline case used in all analyses was 10,000 days after the completion of construction and the opening of the bridge to traffic. The concrete segmental bridge constructed with the balanced cantilever method was load rated two more times at 5,000 days and 15,000 days after the completion of construction and the opening of the bridge to traffic.

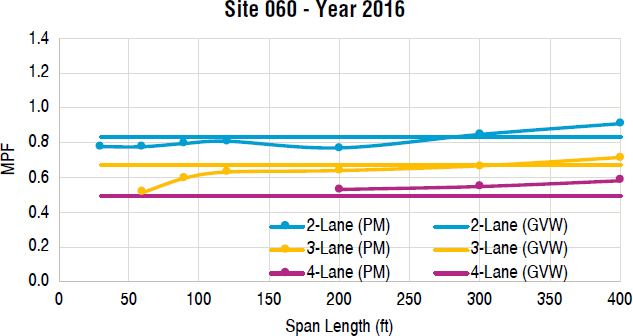

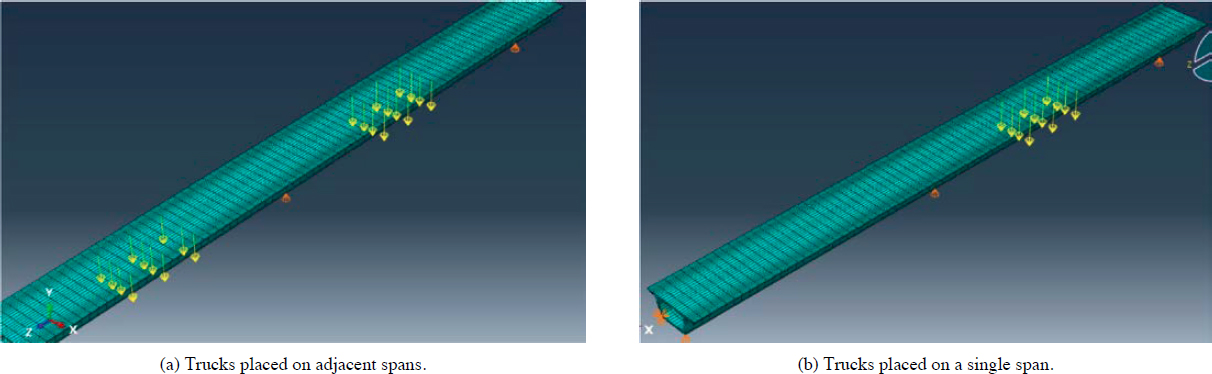

6.4.1.9 Influence of Multiple Trucks

The evaluation of the presence of multiple trucks is conducted in two ways. First, the influence of lane configuration on load rating is determined for the concrete segmental bridge constructed with the balanced cantilever method. This is addressed in Section 6.4.5.10. The considered lane configurations include one based on design lanes (three lanes in this case) and another based on striped lanes (two in this case). For each case, the bridge is rated in the longitudinal and transverse directions. While the number of lanes was based on either design or striped lanes, the position of live load in the transverse direction was determined such that it created the worst-case effects based on the limitations provided in AASHTO MBE (2020). Second, the impact of multiple trucks within a given lane configuration was evaluated by considering the results obtained from the three load rating examples that addressed bridges constructed with the span-by-span, balanced cantilever, and incremental launching method. This situation is addressed in Section 6.4.6.

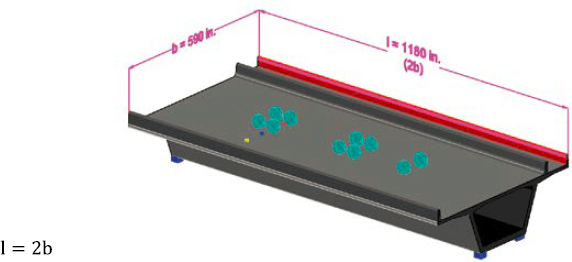

6.4.1.10 Influence of Analysis Technique on Live Load Effects in the Transverse Direction

Computed live load induced strains in the top slab in the transverse direction based on a 2D frame model and influence surfaces as well as on 3D finite element analysis were compared with those measured during a live load test for the Seabreeze Bridge, in Daytona, Florida. The goal of this comparison is to determine the level of conservatism used in the traditional frame analysis and to make recommendations for load rating.

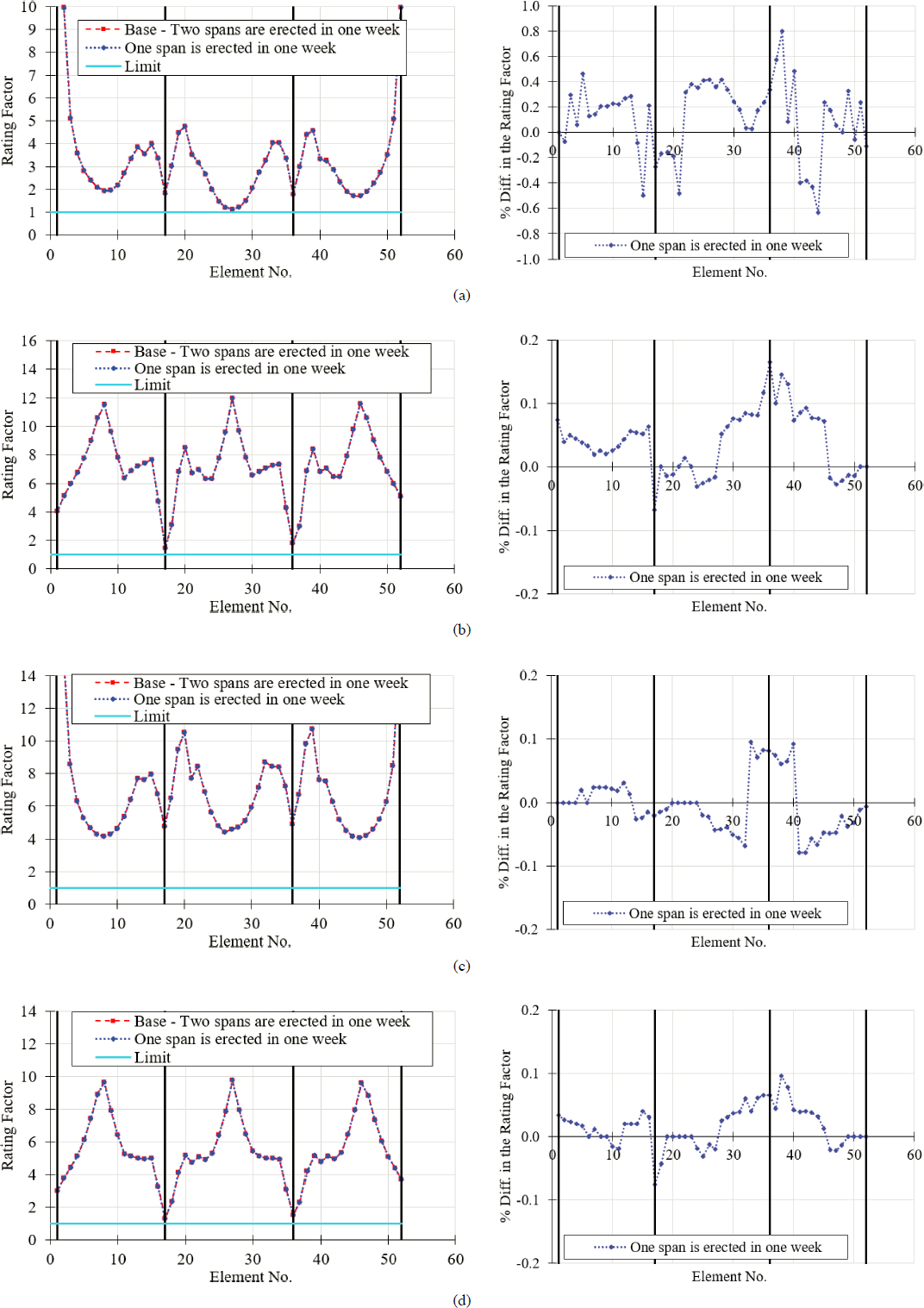

6.4.1.11 Influence of Erection Time

The influence of erection time on load rating factors is investigated for a three-span concrete segmental bridge constructed with the span-by-span method. A comparison of rating factors is conducted assuming two erection scenarios. In the first scenario, it is assumed that two spans are erected each week. In the second scenario, it is assumed that one span is erected each week.

A study of the influence of erection on the balanced cantilever bridge is not included in this report. Such a study would include considering two different erection schedules while maintaining the same production date of the precast segments. In this scenario, the slower erection schedule would lead to the erection of older segments, which would then experience lower time-dependent stress changes, albeit with them having slightly higher stiffness as a function of increased age. In general, for the three-span bridge of Example 2, at some bridge age where time-dependent behavior has ceased, the load ratings of the more slowly erected bridge would be higher at midspan (positive bending) and lower at the piers (negative bending) than those of the bridge erected faster.

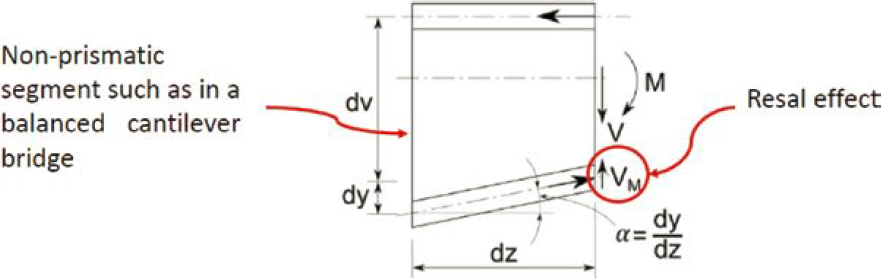

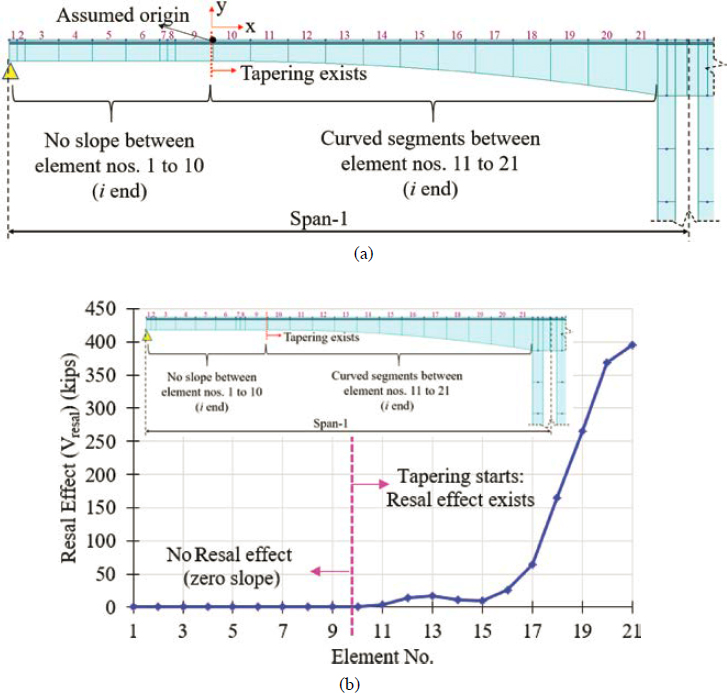

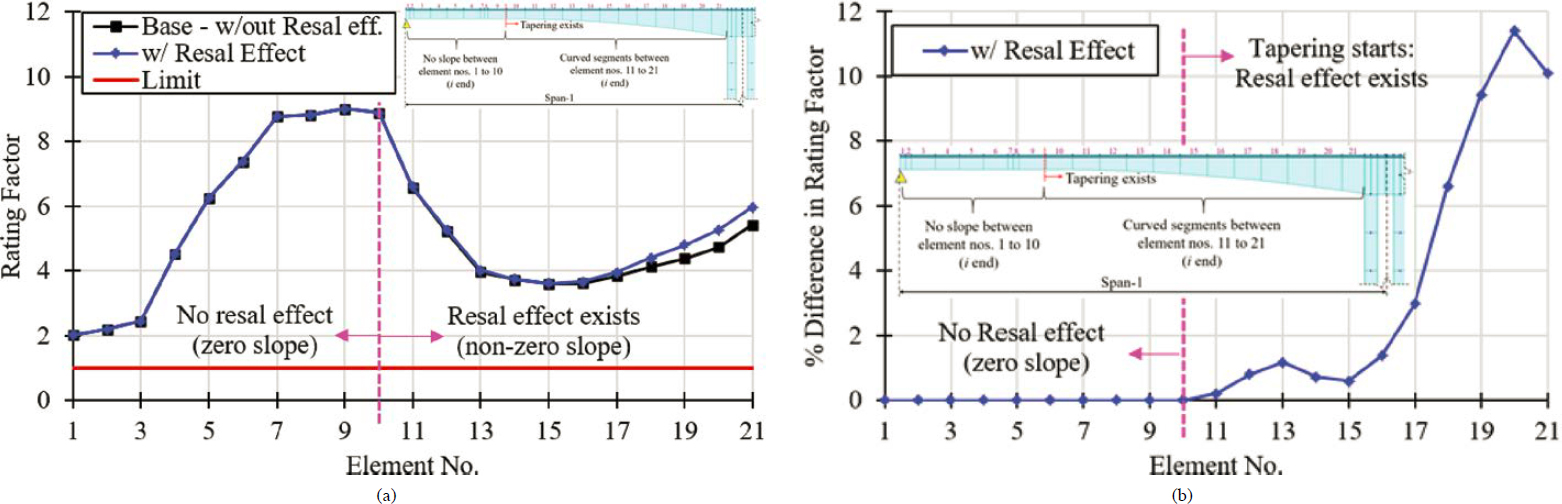

6.4.1.12 Influence of the Resal Effect

The influence of the Resal effect on load rating was investigated for the bridge constructed with the balanced cantilever method. The investigated limit state was vertical shear at the ultimate load level. Rating factors for this limit state were computed once by ignoring the Resal effect, and another time by considering it. The percentage change in rating factors was quantified. Taking account of the Resal effect may improve ratings related to principal tension in the webs.

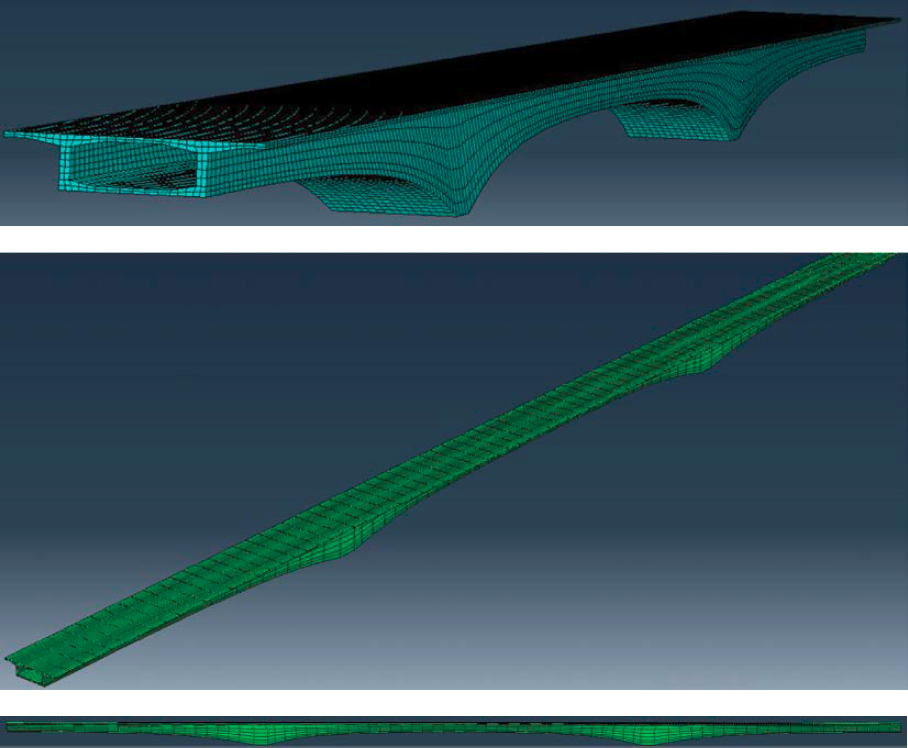

6.4.2 Numerical Modeling Protocol and Load Rating Analysis

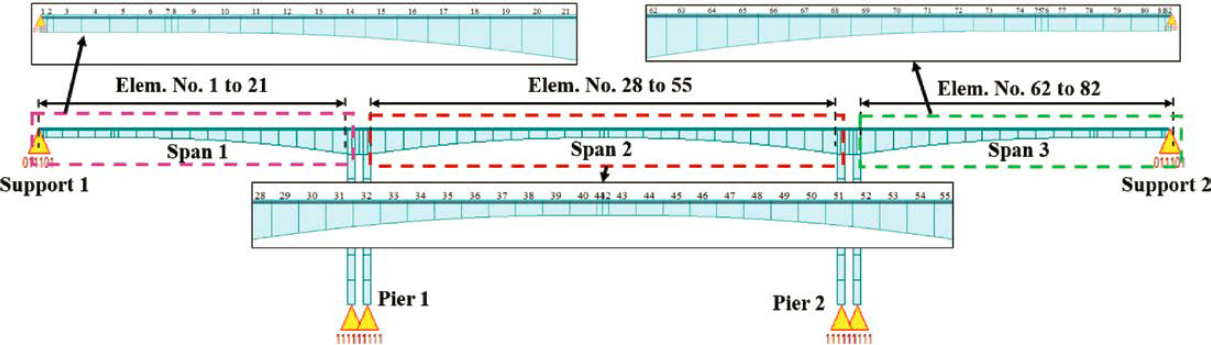

The bridges constructed with the span-by-span, balanced cantilever, and incremental launching methods and discussed in the load rating examples were load rated in the longitudinal and transverse directions.

Longitudinal Direction

In the longitudinal direction, the time-dependent structural analysis was conducted in Midas Civil 2023. The analysis results were exported to an Excel file, which in turn served as an input file for load rating calculations in Mathcad 15. For every segment, at the i-joint (the beginning of the segment) and j-joint (the end of the segment), load demand in terms of axial force, bending moment, shear, and torsion were exported to the Excel file. In addition, for every segment at the i-joint and j-joint, sectional capacities in terms of flexural strength and shear strength, computed in Midas Civil 2023, were exported to the Excel file. These flexural and shear capacities were verified with independent manual calculations based on AASHTO LRFD (2020a) as explained in the load rating examples (Appendix C of the Guideline). Similarly, for every segment at the i-joint and j-joint, the section properties in terms of area, moment of inertia, centroidal axis, first moment of area, area enclosed by shear flow path (including any areas of holes therein), and length of median of web measured on slope from mid-depth of top slab to mid-depth of bottom slab were exported to the Excel file. Once this information was exported to Excel, the load rating factors were calculated for each joint, each limit state, and each load combination. These load rating factors were then plotted as a function of segment number to illustrate their variation and to identify controlling segments and locations. An algorithm was created in Mathcad to compute the load rating factors for each of the cases mentioned at each joint.

Temperature gradient was based on solar radiation zone 3. Stresses created due to temperature gradient (self-equilibrating and secondary axial force and bending moment stresses) were obtained from Midas Civil 2023, although independent manual calculations based on free, restrained, and self-equilibrating stresses were conducted to validate the accuracy of the results. This situation is discussed further in the validation section. The uniform temperature change load case (TU) did not create any stress effects in the bridge constructed with the span-by-span method because the superstructure was free to axially contract or expand. In the bridge constructed by the balanced cantilever method, stresses created due to TU were considered because the superstructure and pier were rigidly connected.

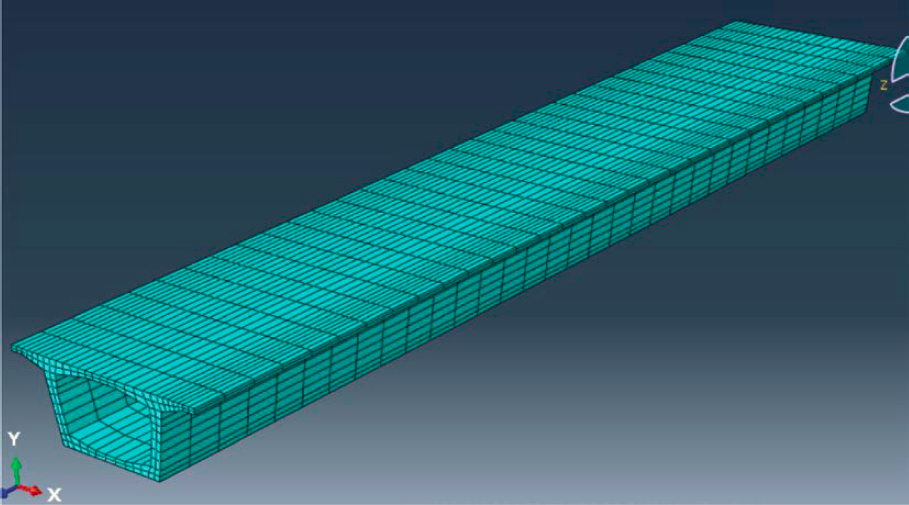

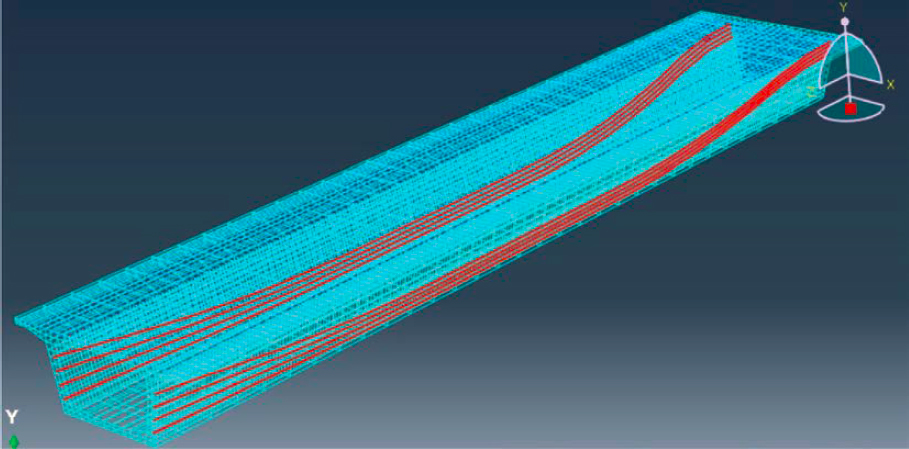

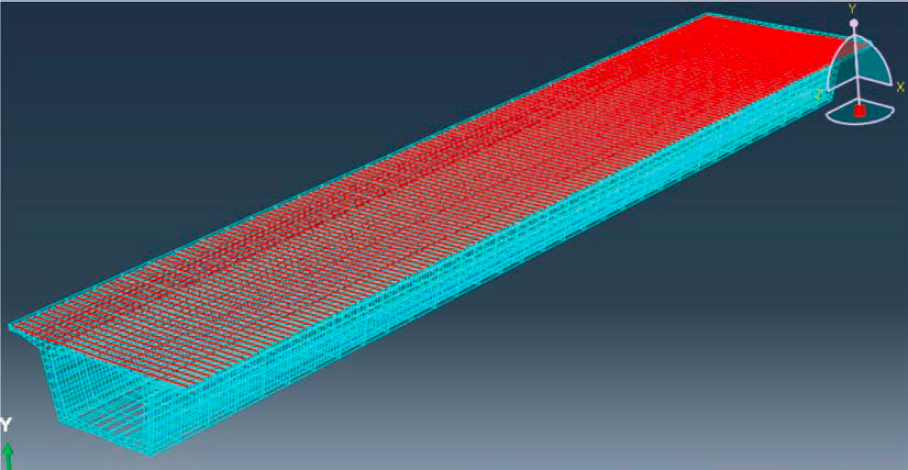

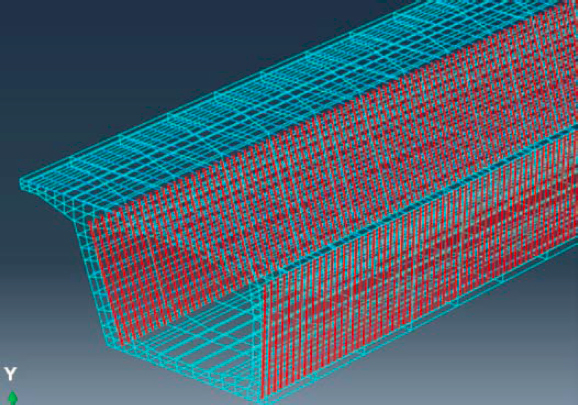

The analytical model used to conduct the time-dependent structural analysis in the longitudinal direction was a 3D model featuring beam finite elements for the concrete segments. Timoshenko beam elements were used for the concrete segments. Each beam element featured a total of six degrees of freedom per node, three translational and three rotational. The use of Timoshenko beam elements rather than Euler-Bernoulli beam elements allowed the consideration of shear deformations. Prestressing effects were simulated using the equivalent load concept based on specified tendon coordinates. The stiffness of the tendons was reflected in the computation of transformed-section properties. The tensile stresses in the tendons, which were used to calculate the equivalent loads, were based on the prestress losses at every construction stage caused by various factors such as creep and shrinkage of concrete, relaxation of prestressing strands, friction losses, anchorage seating losses, and elastic losses or gains. While prismatic concrete segments were used for the bridge constructed by span-by-span method, linearly varying segments were considered for the bridge constructed by balanced cantilever method to capture the variable stiffness of the segments. The variation of depth within a segment was considered to be linear. The pier elements for the bridge constructed with the balanced cantilever method were prismatic elements. The analytical model is capable of capturing (1) staged construction; (2) time-dependent effects; and (3) prestress losses due to creep, shrinkage, relaxation, friction, anchorage set, and elastic loss or gain. Both short-term and long-term prestress losses were considered. Short-term losses included (1) elastic shortening losses (or elastic elongations gains), which were captured through strain compatibility by the analytical model as the structure deforms; (2) anchorage set losses, which were calculated based on specified anchorage set, friction, and wobble factors; and (3) friction losses, calculated based on selected code formula, tendon geometry, and friction and wobble factors. Long-term losses included (1) creep and shrinkage, which were calculated together based on strain compatibility for each construction stage, and (2) relaxation losses which were calculated based on Eq. (6-5) (Magura et al. 1964). The calculation of the relaxation loss was based on an assumed variation of the initial prestressing force at each time step. Eq. (6-5) is similar to the AASHTO LRFD (2020a) Eq. 5.9.3.4.2c-1.

| (6-5) |

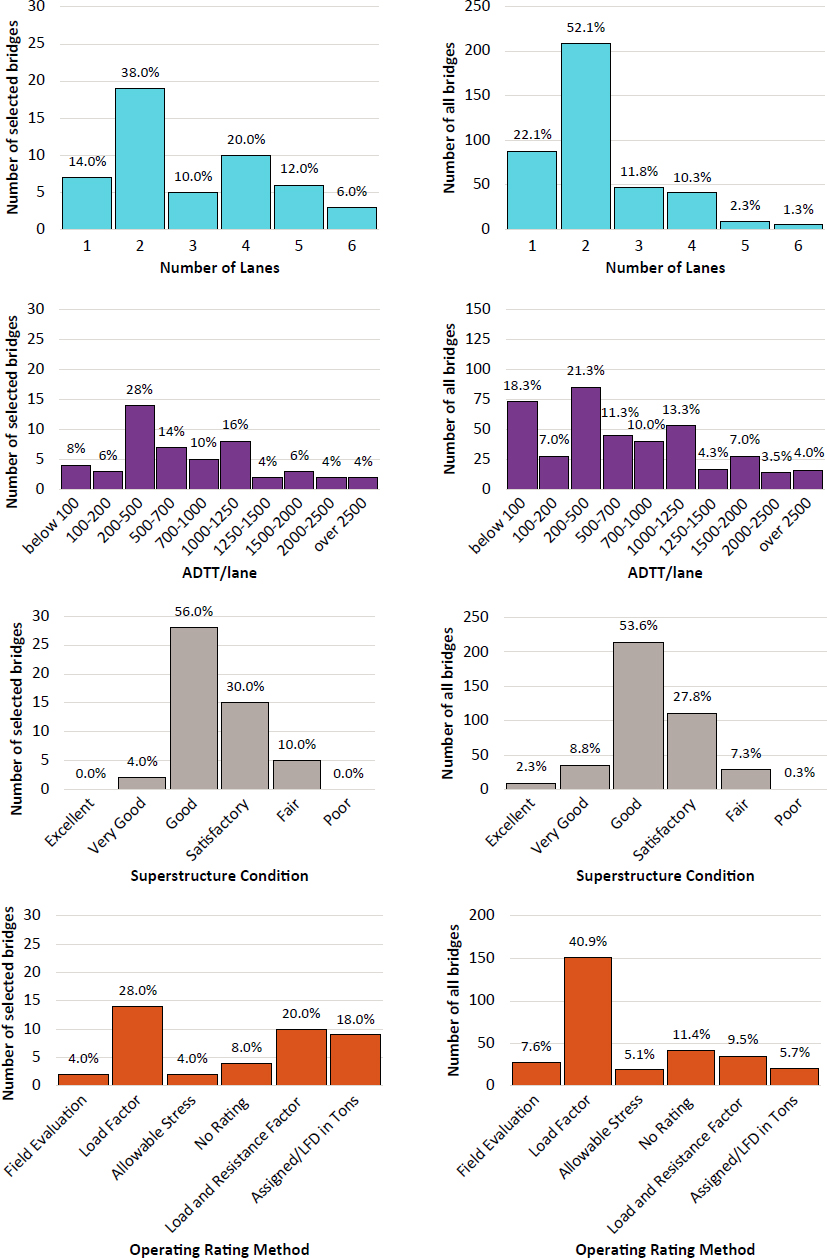

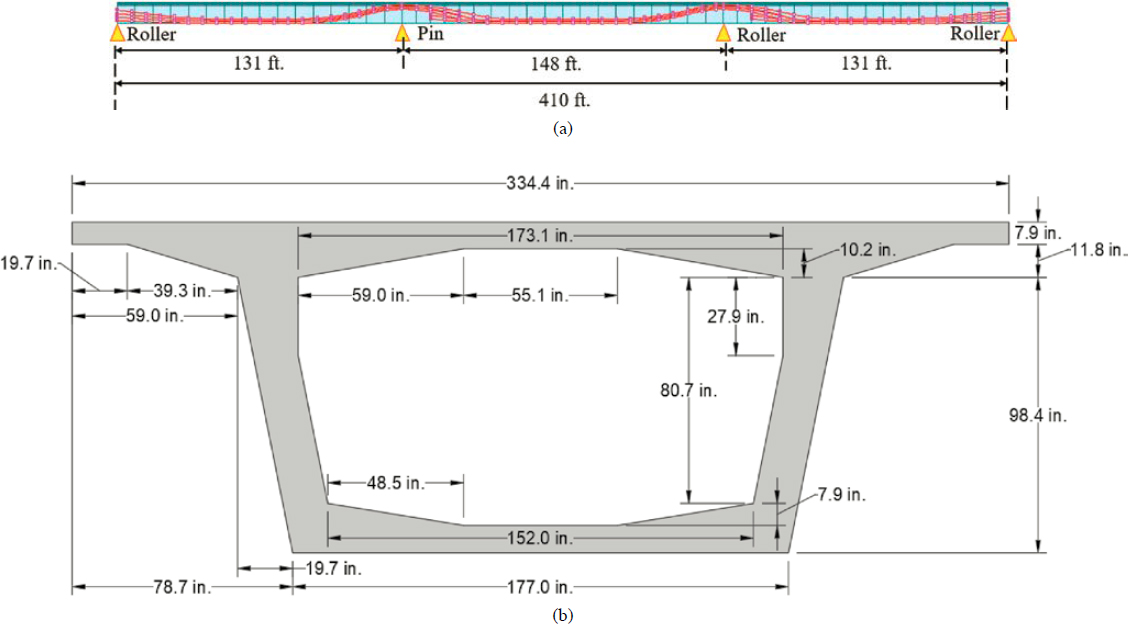

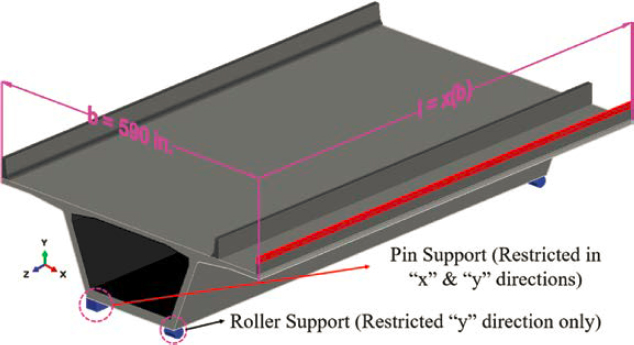

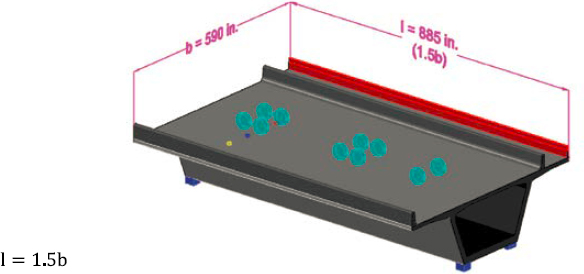

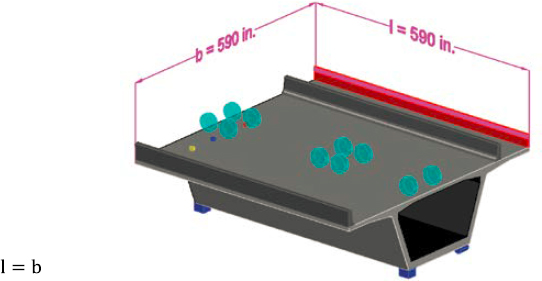

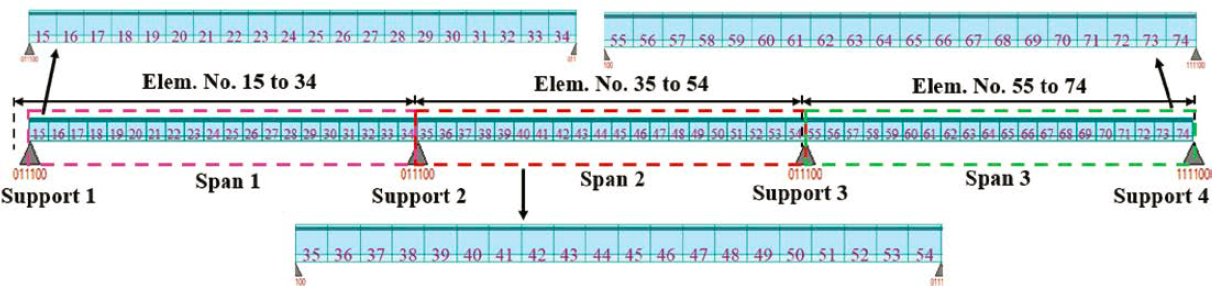

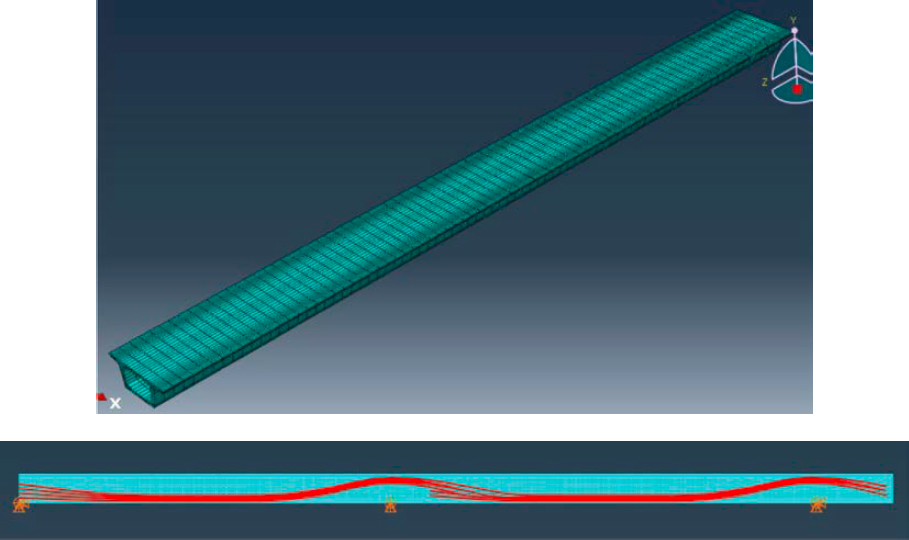

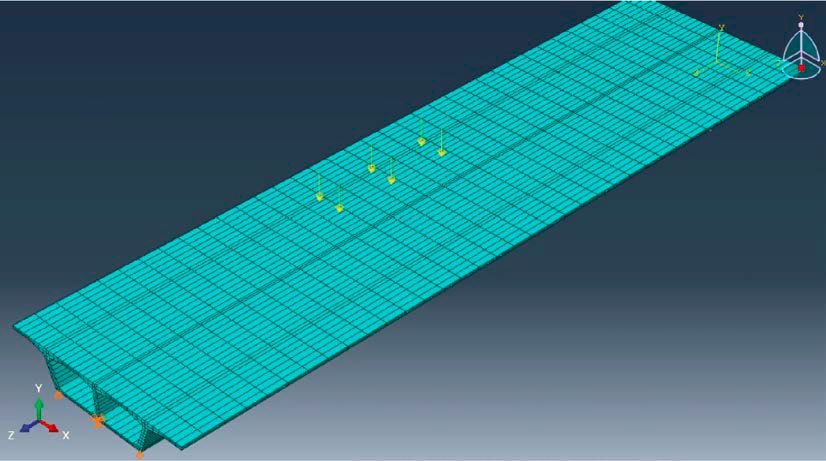

A node located at mid-width of the segment and at the top of the segment was used as the reference node to define the superstructure for the bridge constructed with the span-by-span method as shown in Figure 6-4(a). The selection of the top of the segment as the reference node predefines an offset between the reference point and the centroid of the section. Alternatively, the reference point may be selected at the centroid of the segmental cross section. Although, this creates difficulties when modeling non-prismatic elements for the superstructure because the location of the centroid varies along the span. Tendon coordinates are entered based on the reference node, and tendon eccentricities with respect to the section centroid are calculated based on the predefined offset between the reference node and the centroid of the section. The grouping effect of the tendons, that is, “z” offsets as specified in AASHTO LRFD (2020a) Figure C5.9.1.6-1, should be considered. In some cases, the box sections used in concrete segmental bridges are too deep for this to have a significant effect in the analysis. However, this grouping effect might be impactful in shallower cross sections. Rigid links were used to connect the supports to the reference node for the bridge constructed with the span-by-span method as shown in Figure 6-4(a). In addition, for this bridge, the boundary conditions featured pin-roller-roller-roller conditions, which allowed the superstructure to axially expand and contract. For the support defined as pin, translations in x, y, and z directions were restrained. For the supports defined as rollers, only the translations in y and z directions were restrained. This was done by defining two support points as shown in Figure 6-4(a). In the first support, translations in

y and z directions were restrained, whereas in the second support, only the translations in the z direction were restrained. The provision of rigid links in a triangular fashion as shown in Figure 6-4(a) and the definition of boundary conditions as described previously provide the required torsional stability for the model. Several construction stages were defined as described in the load rating example to simulate the sequential nature of construction. The bridge constructed with the span-by-span method featured precast concrete segments. These segments were activated once their erection was completed.

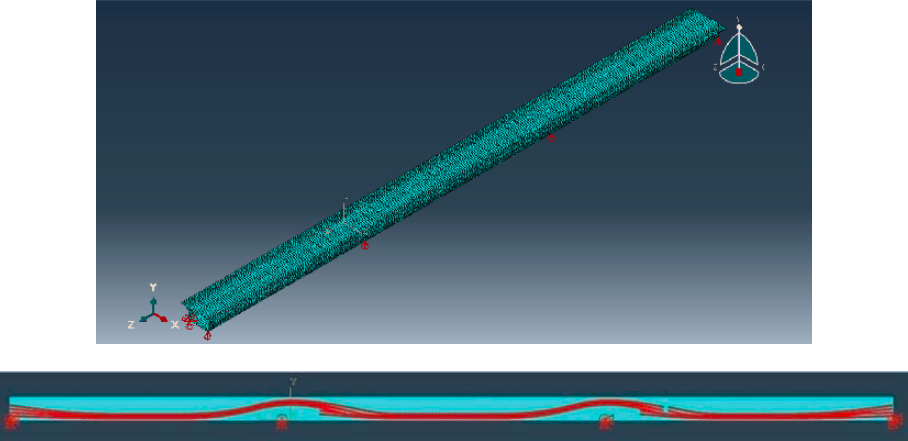

For the bridge constructed with the balanced cantilever method, the piers were rigidly connected to the superstructure, as shown in Figure 6-4(b) (left), and roller supports were defined at the abutments, as shown in Figure 6-4(b) (right). Only one support point was defined at the abutments. For this support point, translations in y and z directions, and rotations about x and z axes were restrained. This created the required torsional stability in the model. Alternatively, the boundary conditions at the abutments could have been defined using the same approach used for the bridge constructed with the span-by-span method. Two rigid links were used to connect the piers to the reference nodes at the top of concrete segmental cross sections over the

piers. To accomplish this, the pier tables (i.e., the superstructure segments over the piers) were partitioned such that the reference nodes in the superstructure segments and those in the piers were in the same plane. The piers were fully restrained at the bottom. The concrete segments for the piers were defined using the centroid as the reference point. Several construction stages were created as described in the load rating example document to simulate the sequential nature of construction. The bridge constructed with the balanced cantilever method featured cast-in-place concrete segments. These segments were activated once the formwork was removed, and the post-tensioning forces were applied. The weight of wet concrete prior to formwork removal was considered to capture the time-dependent effects created by it.

In terms of the notional live load, both truck plus lane and tandem plus lane were considered initially. It was determined that the combination of truck plus lane controlled the load rating in the longitudinal direction. Therefore, the comparative analysis in the longitudinal direction was based on the combination of truck plus lane. Transformed-section properties were used when conducting load rating analysis. The influence of using gross-section properties is addressed in the subsequent sections.

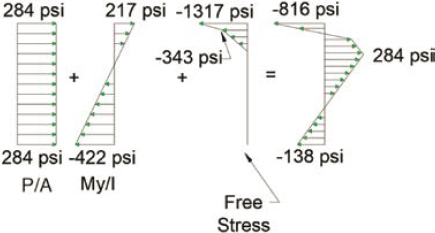

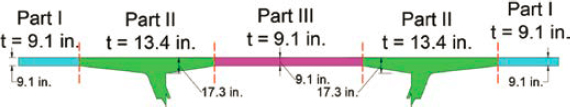

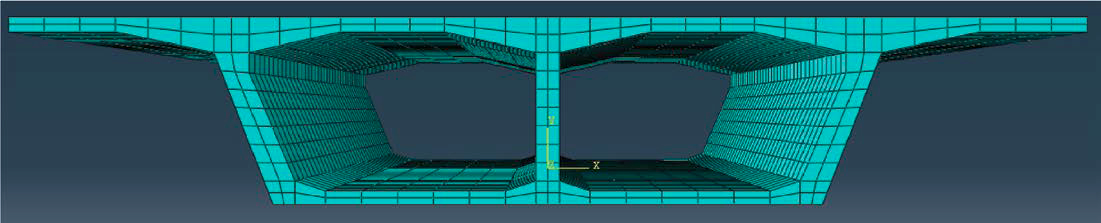

Transverse Analysis

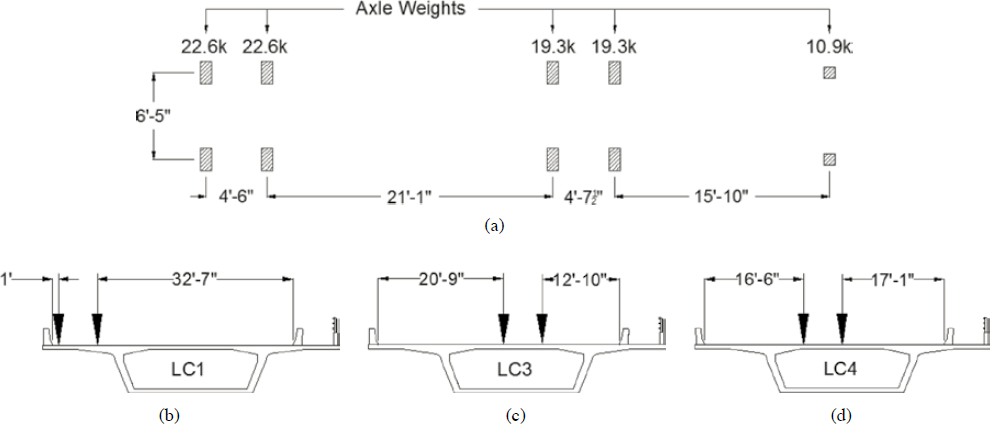

To conduct load rating analysis in the transverse direction, a 2D frame model that represents the segmental cross section was created. Pin and roller supports were located at the intersection of the web and bottom flange as shown in Figure 6-5. The locations of interest where flexural stress at service and flexural strength at the ultimate limit state were computed are illustrated in Figure 6-5 by the red circles. These locations include the root of the cantilever (Point 1), the intersection of the inside face of the web and top slab (Point 2), and the midspan of the top slab (Point 3). A flowchart that describes how the transverse analysis was conducted is presented in Figure 6-6. After the creation of the 2D frame model, all permanent loads, including transverse post-tensioning, were applied on a per-foot basis. Moment due to permanent loads and prestressing were determined at the critical locations.

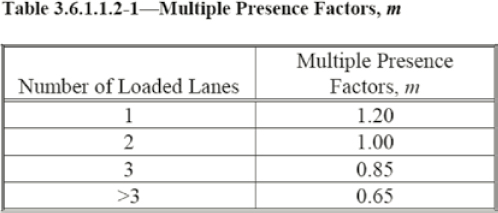

Live load effects were quantified using Homberg (1968) influence surface charts, obtaining fixed end moments, applying these fixed end moments to the 2D frame, and calculating final moments by summing fixed end moments and distributed moments. The notional live load used to conduct load rating analysis in the transverse direction included the HL-93 design truck or tandem loading, whichever produced the worst-case effect. The influence of the presence of multiple trucks was evaluated by considering appropriate MPFs. The guidelines in AASHTO MBE (2018) were followed for the application of vehicular live load. Based on Article 6A.2.3.2 in AASHTO MBE (2018), the center of any wheel load shall not be closer than 2.0 ft from the edge of a traffic lane or face of the curb. In addition, the distance between the center of the wheels of two adjacent trucks should not be less than 4.0 ft.

Secondary prestressing effects and prestresses losses were considered. Secondary moments due to creep and shrinkage were considered; however, they were found to be too small to make an impact. Only one time step was considered to account for time-dependent effects, which was from completion of construction and opening of the bridge to traffic to 10,000 days. Temperature gradient effects were not included in the transverse analysis. Unlike the load rating analysis in the longitudinal direction, which to a certain extent was automated through the use of an algorithm created in Mathcad, load rating analysis in the transverse direction was conducted manually, when it came to the computation of stresses at service and the verification of shear and moment capacities for the top slab obtained from Midas Civil 2023.

6.4.3 Validation of Numerical Modeling Protocol in the Longitudinal Direction

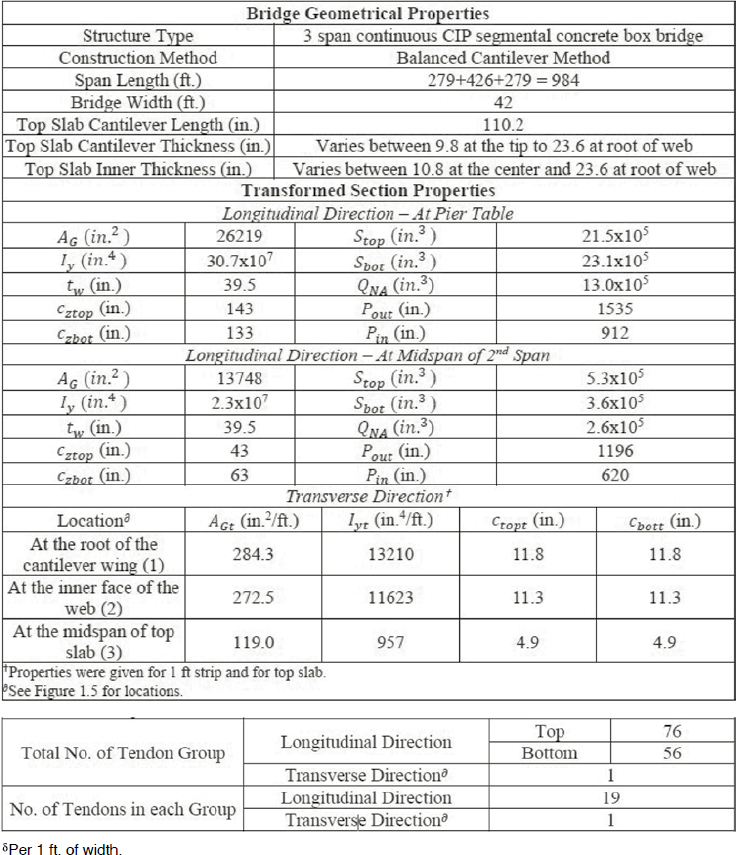

The numerical modeling protocol used in the longitudinal direction was validated by investigating the capability of Midas Civil 2023 to accurately simulate creep, shrinkage, and temperature effects based on a given input. The concrete segmental cross section shown in Figure 6-7 was used to conduct a comparison between theoretical and computed results. The section properties for this concrete segmental cross section are given in Table 6-7. The comparison was conducted between computed and predicted results. Predicted results were based on linear elastic engineering mechanics, and when creep effects were considered, they were based on viscoelastic analysis. Comparison with field data is presented in Section 6.4.7 with respect to live load induced strains in the transverse direction. Since long-term field data in the longitudinal direction included the combined effects of creep, shrinkage, uniform temperature, and temperature gradients, the validation of numerical loading protocol was conducted at the fundamental level between computed and predicted results for each effect independently.

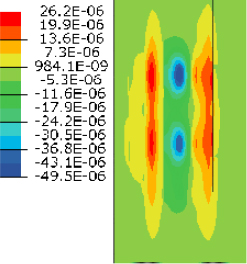

6.4.3.1 Temperature Gradient

The concrete segmental cross section shown in Figure 6-7 was subjected to the positive temperature gradient specified for solar radiation zone 3 in AASHTO LRFD (2020a) as illustrated in Figure 6-8. Cross-sectional stresses calculated based on engineering mechanics were compared

Table 6-7. Section properties.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Area, AG (in.2) | 5,808 |

| Moment of Inertia, IG (in.4) | 3.93 x 106 |

| Concrete Compressive Strength, fc′, (ksi) | 7 |

| Modulus of Elasticity, EC, (ksi) | 4,770 |

| Coefficient of thermal expansion, α, (1/°F) | 6 x 10-6 |

| Centroid of the section measured from bottom, ybot, (in.) | 47.53 |

with those obtained from Midas Civil 2023. It was assumed that the segmental cross section existed in a simply supported beam configuration so that any stresses that were created due to temperature gradient applied at any given section along the span.

To conduct this comparison, piecewise linear functions were established to describe the variation of temperature gradient along the depth of the segmental cross section as shown in Figure 6-9. The top of the section was used as the reference point for defining the variable y (i.e., the variable y, which represents the distance from the top fiber, assumes a positive value

from the top fiber toward the bottom fiber as shown in Figure 6-9). Two piecewise functions are defined.

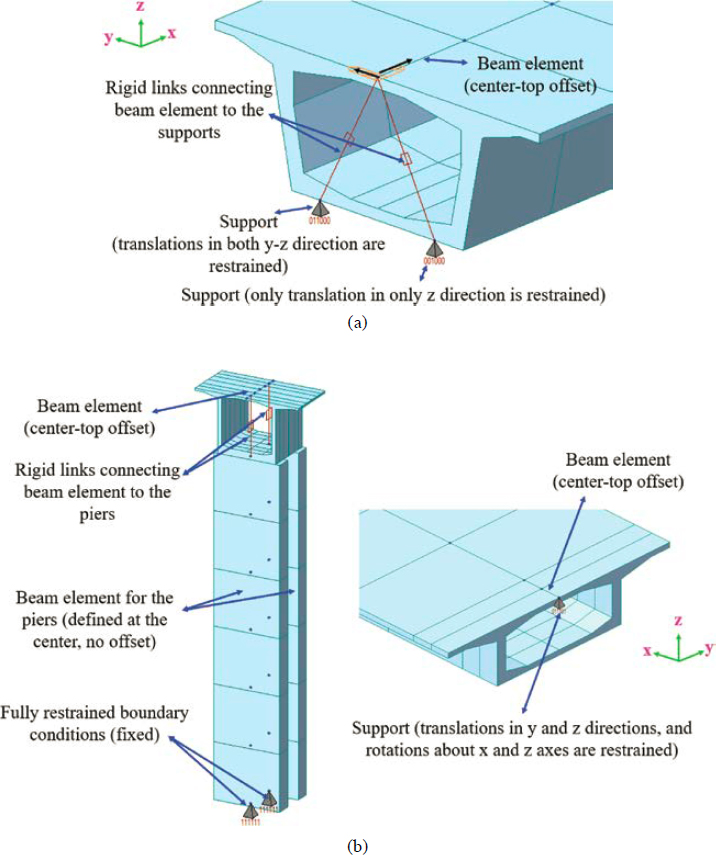

When the temperature gradient is multiplied by the coefficient of thermal expansion, free strains in the segmental cross sections may be obtained. When the free strains are multiplied by the modulus of elasticity, free stresses are obtained as follows.

| (6-6) |

It should be noted that the free strains mentioned cannot materialize because of the nonlinear nature of the temperature gradient and because plane sections before bending will tend to remain plane after bending. In other words, the tendency of each fiber to contract and expand freely is restrained by the adjacent fibers when the imposed strain distribution is nonlinear. The tendency to resist the creation of such free strains gives rise to the formation of restrained strains. If these restrained strains are further multiplied with the modulus of elasticity, restrained stresses, which are equal and opposite to the free stresses are obtained. These free stresses can be integrated to calculate the total axial force and bending moment in the segmental cross section as shown in Eq. (6-7) and Eq. (6-8), where F is the total axial force; M is the total bending moment; Ec is the modulus of elasticity of the concrete; α is the coefficient of thermal expansion; T(y) is the temperature gradient function previously defined; and b(y) is the width of the section as a function of section height.

| (6-7) |

| (6-8) |

Since the functions for temperature gradient are piecewise functions and not continuous ones, the integration is conducted in three parts from y = 0 to y = 4 in.; from y = 4 in. to y = 10 in.; and from y = 10 in. to y = 16 in. The parameter b(y) assumes a value of 336 in., 336 in., and 24 in. for each of the y intervals mentioned, respectively. The results of the integration are shown in Table 6-8 and Table 6-9. The total axial force and bending moment in the cross section are equal to and , respectively.

Table 6-8. Calculation of free axial force in the cross section.

| Part | y (in.) | b(y) (in.) | T(y) (in.) | Fi (kips) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 ≤ y ≤ 4 | 336 | 46 – 8.5y |

F1 = 1115.5 |

| 2 | 4 < y ≤ 10 | 336 | 16 – y |

F2 = 519.3 |

| 3 | 10 < y ≤ 16 | 24 | 16 – y |

F3 = 12.4 |

Table 6-9. Calculation of free bending moment in the cross section at the top.

| Part | y (in.) | b(y) (in.) | T(y) (in.) | Mi (kips-in.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 ≤ y ≤ 4 | 336 | 46 – 8.5y |

M1 = 1795.1 |

| 2 | 4 < y ≤ 10 | 336 | 16 – y |

M2 = 3461.9 |

| 3 | 10 < y ≤ 16 | 24 | 16 – y |

F3 = 148.4 |

Final stresses in the cross section are calculated by superimposing the free stresses with the stresses created by the axial force and bending moment previously mentioned using the formula. This is illustrated in Figure 6-10. The stresses created due to the integrated axial force and bending moment were obtained using the formula P/A + My/I. It should be noted that the net stresses are self-equilibrating in nature, in the sense that if the net stress diagram were to be integrated along the segmental cross section, the net axial force and bending moment would be zero, since there are no externally applied forces. This check can be used to ensure that the calculations are conducted correctly. However, it should be noted that this check applies to simply supported configurations, where restrained axial forces and bending moments arising due to the statical

indeterminacy of the beam do not exist. For continuous beam superstructures, the integration of cross-sectional forces should equal the externally applied restrained forces. It is also worth noting that typically, in stress analyses that include temperature gradient, the gradient is assumed to form over a relatively short time (such as within 8 hours). Therefore, temperature gradient-induced creep effects are typically ignored. If the temperature gradient is sustained over a longer period, stresses created because of it will be relieved to a certain extent.

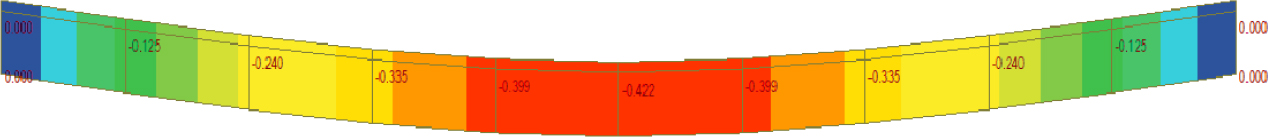

The self-equilibrating stresses mentioned were compared with those obtained from Midas Civil 2021 as shown in Figure 6-11. The results were identical, which shows that Midas Civil 2023 can compute stresses due to the defined temperature gradient accurately.

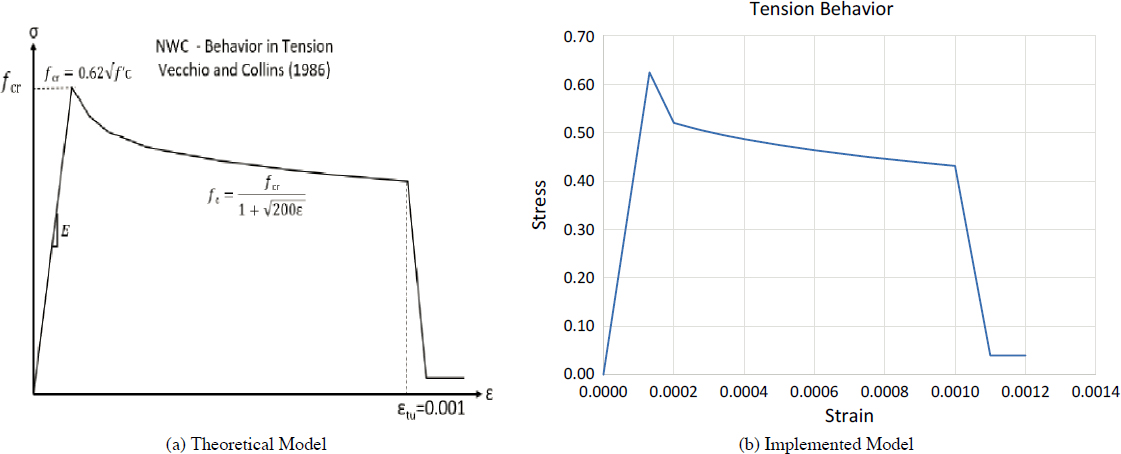

6.4.3.2 Creep

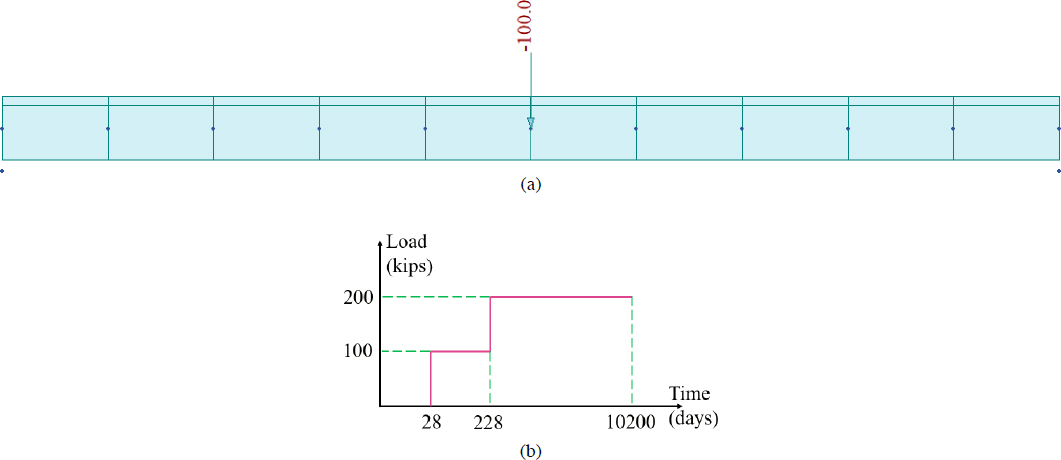

The concrete segmental cross section described in the previous section was used in the following problem to investigate the capabilities of Midas Civil 2023 to simulate creep effects. The segmental cross section was used in a simply supported beam configuration. The age of concrete was assumed to be 28 days and the modulus of elasticity was assumed to remain constant (i.e., no aging effect) and assumed a value of 4,770 ksi over the period considered in this exercise. It should be noted that while Midas Civil 2023 is capable of simulating the aging effects through the use of a time-varying modulus of elasticity, which is obtained based on a time-varying compressive strength function, the aging effect was ignored. A load of 100 kips was applied at the concrete age of 28 days and kept constant until 228 days. An additional 100 kip load was applied at the age of 228 days and kept constant until the age of 10,200 days. The elevation of the beam, the applied load, and the loading history are provided in Figure 6-12. The beam was assumed to be composed of plain concrete to directly investigate creep effects. Self-weight effects were ignored.

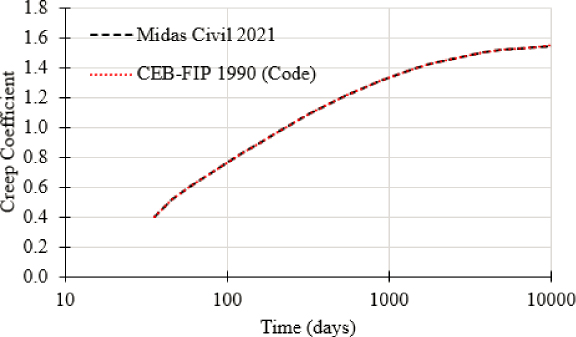

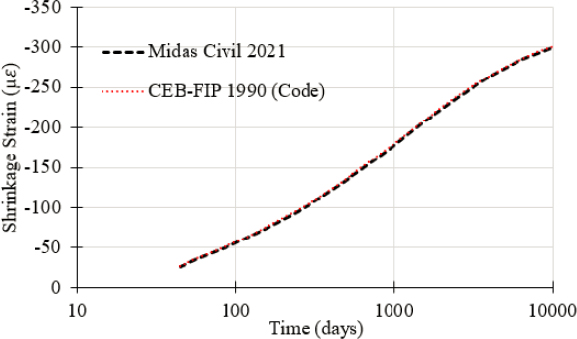

Creep effects at the material level were based on the CEB-FIP (1990) model. The relative humidity was assumed to be 70%. The type of the cement was assumed to be normal cement.

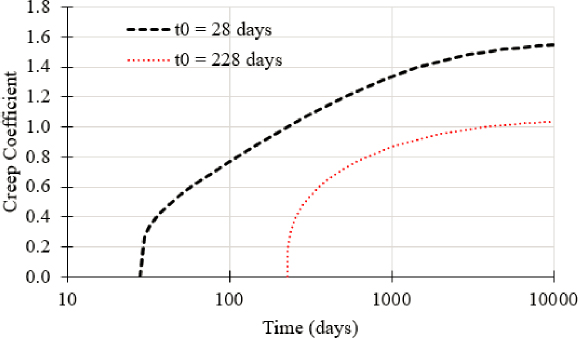

Only creep effects were examined (i.e., shrinkage was excluded to focus the validation on creep). The ability of Midas Civil to accurately simulate creep effects at the material level based on the specified model is illustrated in Figure 6-13, where the loading age was assumed to be 28 days. Since there are two loading events specified in the problem statement, two separate creep curves were used with loading ages of 28 days and 228 days, respectively. These two separate creep curves are illustrated in Figure 6-14.

Creep effects were calculated using the principle of superposition. The time-dependent strain at any concrete fiber can be calculated by summing the elastic and creep strains due to initial stresses, and elastic and creep strains due to changes in stress as shown in Eq. (6-9), where εt is total strain at time t; σ0, σ(τ) is stress at time t0 and τ, respectively; E0, E(τ) is modulus of elasticity at times t0 and τ, respectively; and φt,t0, φ(t, τ) is creep coefficient at time t due to load applied at time t0 and τ. The first expression (i.e., the one before the integral) represents the elastic and creep strains due to a stress applied at time t0. The second expression (the integral term) represents the elastic and creep strains due to changes in stress in the time interval t0 to t.

In this exercise, since the beam was simply supported, and consisted of plain concrete, there was no strain redistribution at the cross-sectional or member level, therefore, the second term did not apply. In the first expression, the ratio represents the initial elastic strain, represents the creep strain, and represents the total strain due to the initially applied loads.

| (6-9) |

Two time intervals were considered: (1) from 28 days to 228 days, and (2) from 228 days to 10,200 days. A total of three creep coefficients were obtained for these two time intervals to calculate creep deformations at each time step as shown where ϕ(t,t0) represents the creep coefficient at time t based on the loading age of t0 days. The creep coefficient represents the ratio of creep strain to the initial elastic stress-induced strain and can assume any value greater than zero.

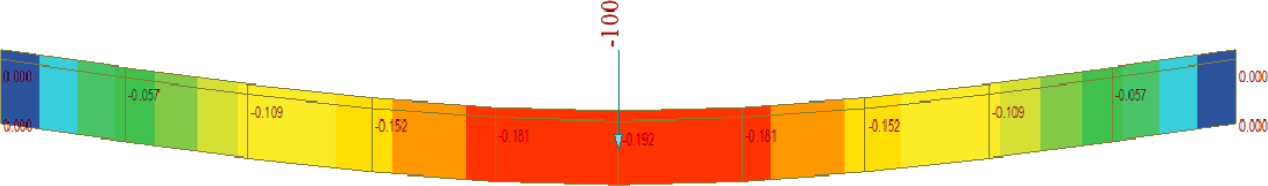

The immediate deflection caused by the 100 kips applied at 28 days load can be calculated using the well-known formula for a simply supported beam loaded at midspan where P is the applied load; L is the beam length; E and I are the concrete modulus of elasticity and moment of inertia of the section, respectively. The immediate deflection is equal to 0.192 in. as shown in Eq. (6-10). The same immediate deflection would be obtained for the second concentrated load applied at 228 days since the modulus of elasticity was assumed to remain constant in this example. Figure 6-15 shows that the immediate deflection was calculated accurately by Midas Civil 2023.

| (6-10) |

Since the simply supported concrete segmental beam considered in this example was assumed to be composed of only concrete (i.e., no tendons) the additional creep deflection may be calculated using Eq. (6-11) and is directly proportional to the creep coefficient. It should be noted that this equation is only valid for plain concrete and assumes that compressive creep is equal to tensile creep (a common assumption in time-dependent structural analysis).

| (6-11) |

Creep strain can be further calculated as described in the Eq. (6-12), where εcc(t, t0) is the creep strain at time t due to the load applied at t0; ϕ(t, t0) is the creep coefficient at time t due to the load applied at t0; and Ec is the modulus of elasticity at 28 days, which needs to be determined based on the formula given in the relevant code (not the one defined under material properties in Midas Civil 2023).

| (6-12) |

In the CEB-FIP (1990) code, the modulus of elasticity of the concrete at 28 days was calculated based on the Eq. (6-13) where fc′ is the concrete compressive strength at 28 days, where fc′ and Ec are in MPa.

| (6-13) |

Midas Civil 2023 does not use the Ec value provided under material properties (4,770 ksi) but uses Eq. (6-13) for the calculation of the creep strain, and hence creep deformations. Immediate deflections were calculated based on the Ec value provided under material properties. Using the CEB-FIP (1990) code and assuming fc′ = 7 ksi concrete, the Ec value was calculated as follows.

| (6-14) |

In this example, the creep deformation was calculated as follows:

| (6-15) |

From t0 = 28 days to t1 = 228 days, the creep coefficient ϕ(228,28) was calculated as 0.998 as shown in Eq. (6-15). The creep deformation at the age of 228 days was expected to be 0.164 in. as shown in Eq. (6-16). This calculated creep strain from 28 days to 228 days was compared to that obtained from Midas Civil 2023. Figure 6-16 suggests that the calculated and computed creep deformations for this time step are identical. It should be noted that these deformations are those induced by creep only and do not include elastic deformations.

| (6-16) |

The total creep deflection between 228 days and 10,200 days can be calculated as shown in Eq. (6-17). This predicted creep deformation was compared with that obtained from Midas Civil 2023. Figure 6-17 suggests that the results are rather similar (0.262 in. calculated versus 0.258 in. computed, i.e., 1.5% error). Again, these deformations are those induced by creep only and do not include elastic deformations.

| (6-17) |

When the total creep deformations were considered, the calculated total creep deformation was equal to 0.426 in. as shown in Figure 6-18. The computed total creep deformation obtained from Midas Civil was equal to 0.422 in. (0.9% error).

| (6-18) |

The total calculated and computed deflections (immediate plus creep deflections) were compared in Table 6-10 for the three times considered in this example. Here, the deflections at 228 and 10,200 days were total deflections and included elastic as well as creep deflections. The ratio of computed to calculated deflections was 1.0 and the V was 0.4%, which suggests that Midas Civil 2023 is capable of predicting accurately creep effects.

6.4.3.3 Shrinkage

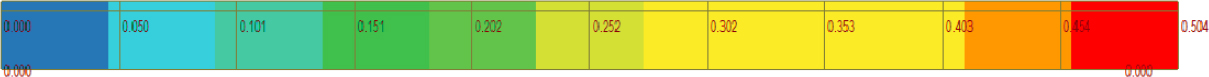

The simply supported concrete segmental beam mentioned previously was used to conduct a comparison between calculated and computed axial deformations due to a specified shrinkage strain. Since the beam was simply supported (i.e., pin supported on one end and roller supported at the other) it was subjected only to axial deformations and no stresses when subjected to uniform shrinkage. The specified shrinkage was based on CEB-FIP (1990). The ability of Midas Civil to predict shrinkage strains based on this model is illustrated in Figure 6-19. It was assumed that the beam was moist-cured for 28 days. The shrinkage strain at 10,200 days was calculated as −301 µε.

Considering that the beam length is 100 ft, the shrinkage-induced axial deformation at 10,200 days is 0.36 in. An identical axial deformation was computed by Midas Civil 2023 as shown in Figure 6-20.

| (6-19) |

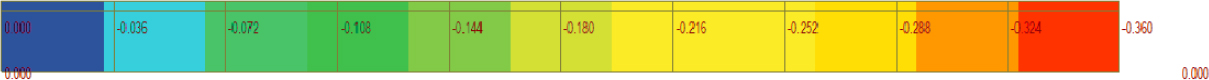

6.4.3.4 Uniform Temperature Changes

The simply supported concrete segmental bridge mentioned previously was subjected to a uniform temperature change ∆T = +70 °F. The coefficient of thermal expansion was assumed

Table 6-10. Summary of the analysis results for creep deformation.

| Time (days) | Net Midspan Deflection (in.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical deflection, ∆theoretical, (in.) | Midas Civil 2023 prediction, ∆Midas, (in.) | ||

| 28 | 0.192 | 0.192 | 1.00 |

| 228 | 0.548 | 0.548 | 1.00 |

| 10,200 | 0.810 | 0.806 | 0.99 |

| Average | 1.00 | ||

| St. Dev. | 0.00 | ||

| V (%) | 0.40 | ||

to be 6 p 10−6/°F. The axial elongation in the beam was calculated as 0.504 in. An identical axial elongation was predicted by Midas Civil 2023 as shown in Figure 6-21.

| (6-20) |

6.4.4 Comparative Analysis for a Concrete Segmental Bridge Constructed with the Span-by-Span Method

6.4.4.1 Description of the Bridge

The concrete segmental bridge used in the load rating example and constructed with the span-by-span method was used to conduct a comparative analysis. The elevation of the bridge and its cross section are shown in Figure 6-22. Detailed information about this bridge is provided in Appendix C of the Guideline.

6.4.4.2 Influence of Creep and Shrinkage Model on Load Rating

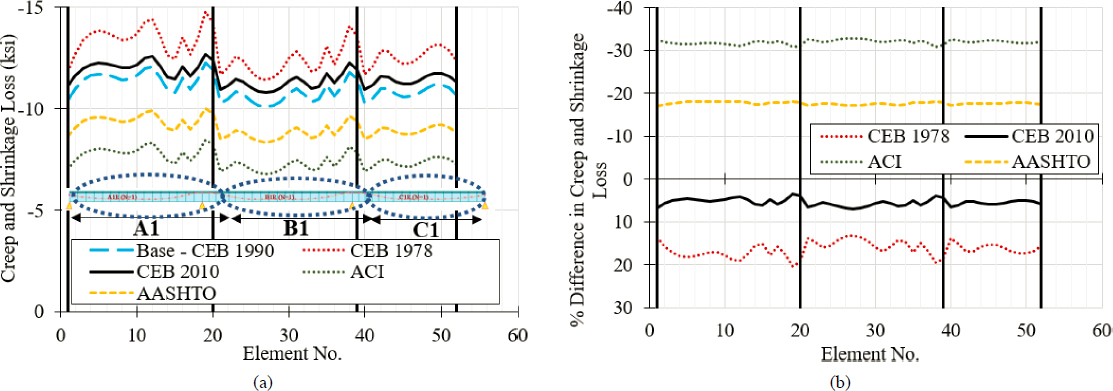

The influence of various creep and shrinkage models was investigated by load rating the abovementioned bridge several times based on different creep and shrinkage models. The considered models included (1) AASHTO LRFD (2020a), (2) FIB 2010, (3) CEB-FIP 1990, (4) CEB-FIP 1978,

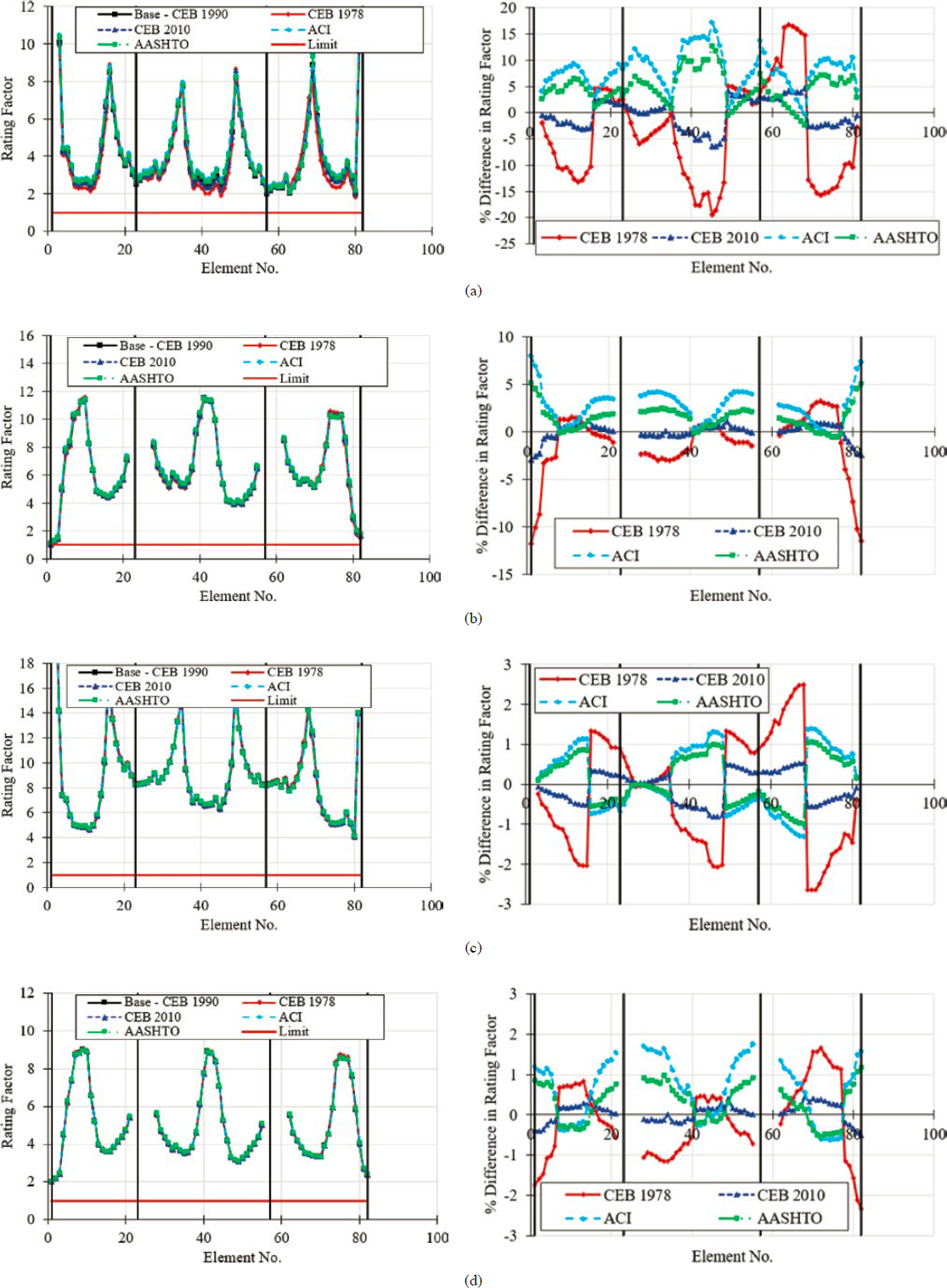

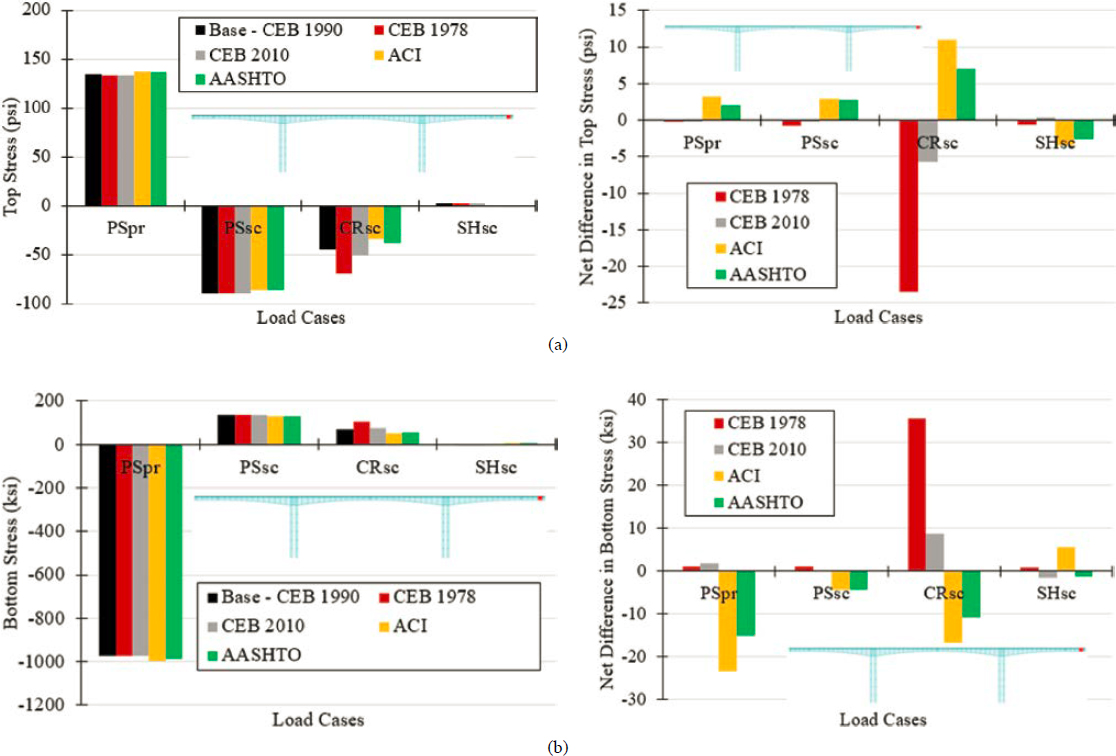

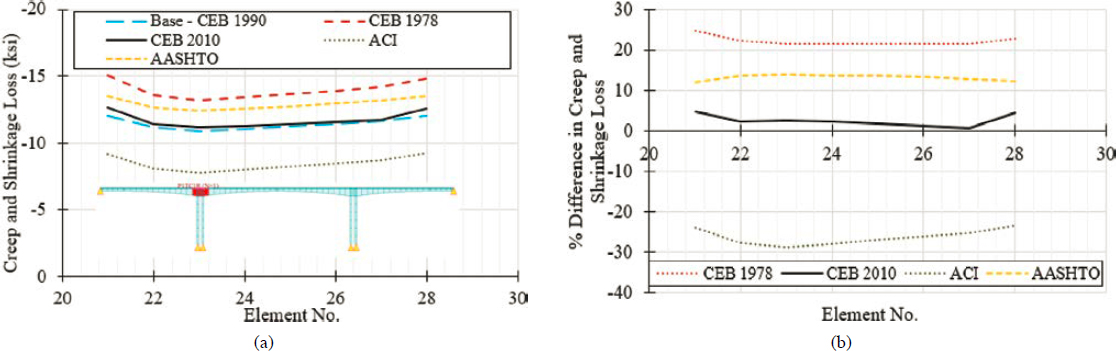

and (5) ACI 209R.92. The load rating of the bridge was conducted at 10,000 days after the completion of construction and opening of the bridge to traffic. Figure 6-23 suggests that rating factors were mostly influenced by the service flexure limit state, in which the maximum percent change in rating factors was 9%, although the maximum change is noted for joints that are located in the vicinity of the second pier from the left. The controlling segment for this case was located at midspan of the second span. The percent change in the load rating factors for this segment for service flexure was less than 5%. These changes in rating factors could be impactful if the bridge was on the verge of a passing rating. The selection of creep and shrinkage models was less influential on the principal tensile stress limit state, in which the maximum percent change in rating factors was 3%. The impact of the selection of creep and shrinkage models was reduced further for the flexural strength limit state, in which the maximum percent change in rating factors was no greater than 1%. Similar observations were made for the shear strength limit state in which the maximum percent change in rating factors was 1.5%. While the selection of the creep and shrinkage models caused up to a 9% change in rating factors for service flexure, this change was much smaller than the change observed between the creep coefficients and shrinkage strains at the material level as illustrated in Figure 6-24. Concrete creep affected stresses at service through the variation of the prestressing force due to creep-induced prestress loss as well as through the development of creep-induced secondary moments, which were created as a result of stress redistribution. The use of various creep models results in some changes in top and bottom stresses caused by primary and secondary prestressing effects as well as secondary creep effects as shown in Figure 6-25. Top and bottom stresses were computed at 10,000 days. Although there was some variation in the stresses caused by secondary creep effects depending on each creep model chosen, this load case had a limited influence on net stresses at service. Figure 6-26 shows the variation of creep and shrinkage-induced prestress loss as a function of different models for three tendon groups (A1, B1, and C1). In this figure, the vertical black lines

indicate the start and end locations of each tendon group. While there was some variation in creep and shrinkage-induced losses, this variation was smaller than 3.4 ksi at any given point when CEB-FIP 1990 is considered as a baseline. When considering the magnitude of the jacking stress as well as losses caused by other phenomena, this explains why the selection of creep and shrinkage models has a limited influence on stresses at service and consequently rating factors. Naturally, the time when the load rating was conducted affected the creep coefficient and shrinkage strain, and the reported differences in rating factors were a function of this time. However, despite a notable difference in the creep coefficients at 10,000 days, the change in rating factors was limited. Other conclusions were drawn for the bridge constructed with the balanced cantilever method. In addition, for the balanced cantilever bridge, the influence of rating time on load rating was examined.

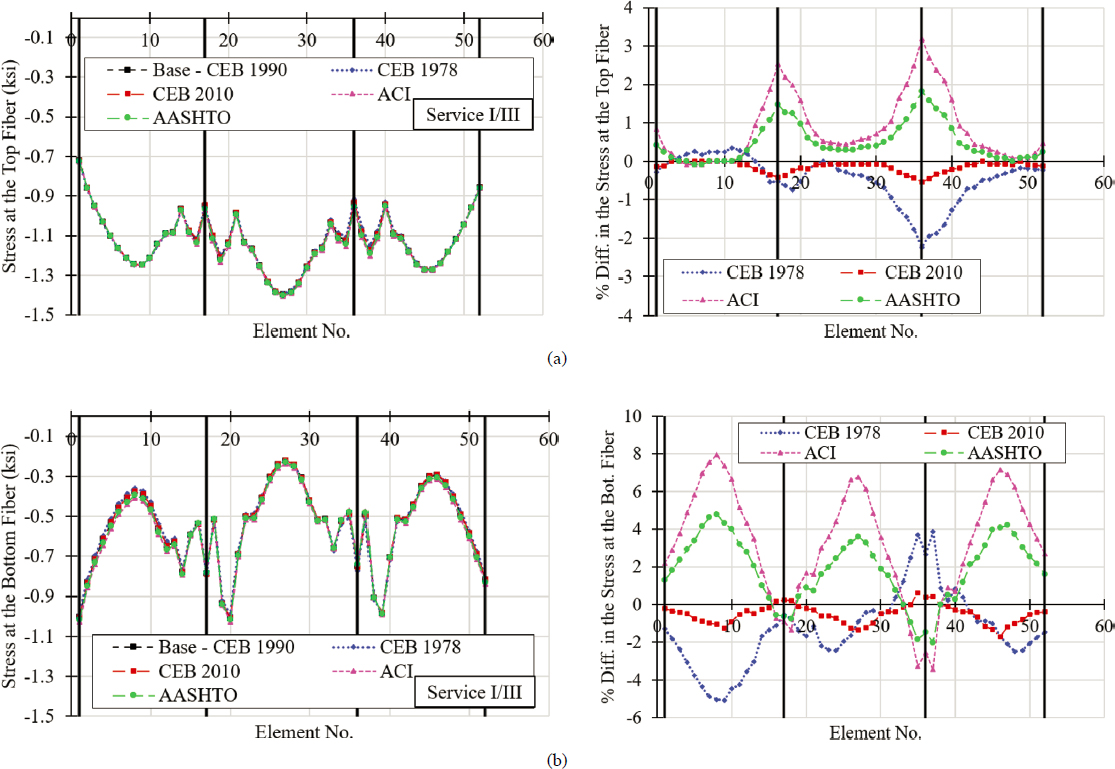

A separate evaluation was conducted to determine the impact of the selected creep and shrinkage model on stresses at service. Service I/III load combinations were used, such that if the live load created tension, the live load factor was taken as 0.80, otherwise it was taken as 1.0. Service I/III load combinations that featured positive and negative uniform temperature changes as well as positive and negative temperature gradients were considered, and the envelope values were used to examine the impact of creep and shrinkage model selection on service flexural stresses. Figure 6-27 illustrates this impact in terms of top and bottom fiber stress magnitudes as well as in terms of a percent change when the CEB MC 1990 model was used as the benchmark. The maximum percent difference in top and bottom fiber stresses is 3.2% and 8%, respectively. The maximum difference in top and bottom fiber stresses is 30 psi and 2 psi, respectively. Therefore, it can be concluded that the impact of creep and shrinkage model selection on stresses at service is minimal. A similar conclusion is presented in the commentary of AASHTO LRFD (2020a) Article C5.12.5.2.3.

6.4.4.3 Influence of Temperature Gradient on Load Rating

The consideration of temperature gradient in terms of its characterization and its impacts on cross-sectional stresses has been a source of controversy in the segmental bridge industry. Roberts-Wollmann et al. (2002) provide a good summary of some of the challenges associated with this load case, including a historical account of key changes related to this subject. AASHTO LRFD (2020a) Article C3.12.3 notes that “If experience has shown that neglecting temperature gradient in the design of a given type of structure has not lead to structural distress, the Owner

may choose to exclude temperature gradient.” Multibeam bridges are provided as an example for which judgment and experience should be considered.

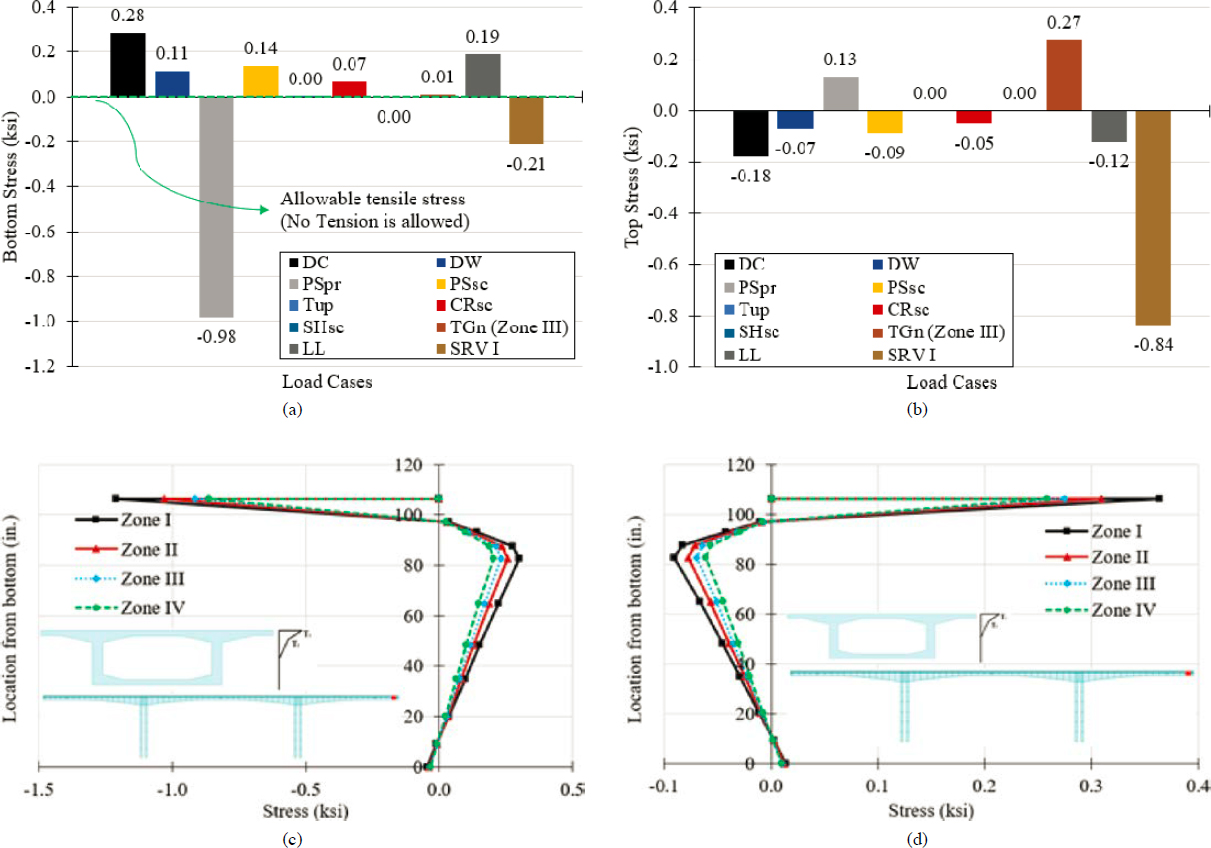

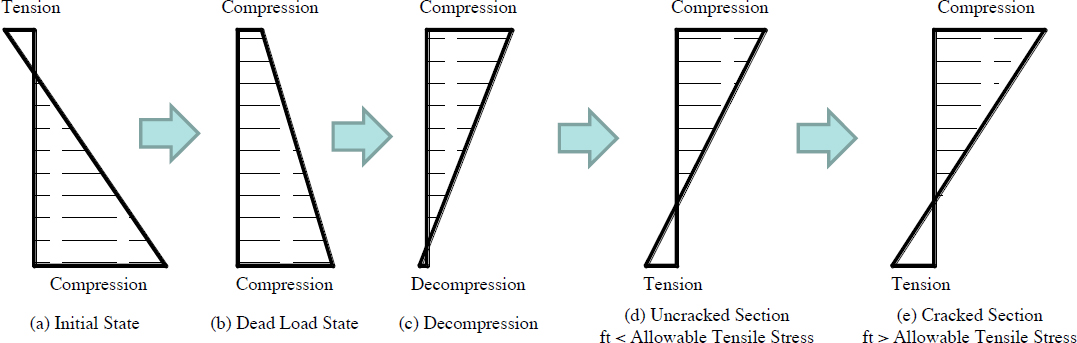

Figure 6-28 shows the contribution of each load case in the computation of the bottom fiber stress in a segment located at midspan of the second span. The use of Service I (SRV I) load combination results in a net compression (0.02 ksi) (i.e., no tension) at the bottom fiber in the longitudinal direction. As expected, the load cases that created flexural tension in the bottom fiber were dead loads (DC and DW), secondary effects of prestressing (PSsc), and live loads (LL). The competing effects of primary and secondary prestressing forces are worth noting. The positive effects of primary prestressing were reduced to a certain extent by the secondary prestressing forces since the controlling segment was located at midspan. The ratio of dead load (DC+DW) induced bottom fiber stress to that induced by live load was 2.6.

The positive temperature gradient (TG) based on AASHTO LRFD (2020a) solar radiation zone III caused considerable flexural tensile stress at the bottom fiber (0.20 ksi). Tensile stresses caused by the positive temperature gradient were 74% of those caused by live load. While in this case, the inclusion of TG effects did not result in an inventory rating factor smaller than 1.0, the inclusion or exclusion of temperature gradient as a load case had a strong impact on the resulting rating factors. Figure 6-28(c) shows the distribution of cross-sectional stresses caused by the positive temperature gradient based on different solar radiation zones. Positive temperature gradient alone can create tensile stress in a considerable portion of the cross section,

although this is counterbalanced to a certain degree by the primary effect of prestressing. The magnitude and distribution of temperature gradient-induced stresses depend largely on the concrete segmental cross-sectional shape. It is worth noting in Figure 6-28(c–d) that the intensity of flexural stresses caused by temperature gradient varies as a function of the selected solar radiation zone with solar radiation zone 1 creating the largest flexural stresses and zone 4 creating the smallest ones. Therefore, when local reliable research-based data exist for the temperature gradient, such data may be used in lieu of AASHTO LRFD (2020a) prescribed temperature gradient to benefit load rating.

In terms of additional posting mitigation considerations, Corven Engineering (2004) provides the following discussion for longitudinal tension in epoxy joints. It is noted that because the bond usually exceeds the tensile strength of concrete in properly prepared epoxy joints, tensile stresses may be accepted as a function of the location and quality of the epoxy joint as follows:

- For top fiber stresses on the roadway surface, no tension is permitted for all load rating calculations.

- For bottom fiber stresses:

- Allow 0.2 ksi tension at good quality epoxy joints (i.e., no leaks and fully sealed).

- No tension allowed for poor quality epoxy joints (i.e., leaky or not filled gaps).

While these suggestions are presented in terms of additional posting mitigation considerations for longitudinal tension in epoxy joints caused by any load case, tension created by temperature gradients presents an example of when this avenue may be mobilized.

To further illustrate the impact that temperature gradient can have on stresses at service, the stresses caused by each load case on the top fiber are illustrated in Figure 6-28(b). In this case, the load combination considered included a positive temperature gradient, which created compression on the top. It is worth noting the compressive stress caused by temperature gradient is higher than that caused by dead loads. Since compressive stresses are typically not an issue, this is not a concern; it was illustrated here to highlight the potential of TG as a load case in terms of creating significant compressive and tensile stresses at service. When negative temperature gradients were considered, significant tensile stresses were created in the top fiber [Figure 6-28(d)], which may be more vulnerable to deterioration compared to the bottom fiber. However, these spikes in tensile stress apply only to a limited depth, which as noted previously, depends largely on the cross-sectional shape, and are temporary.

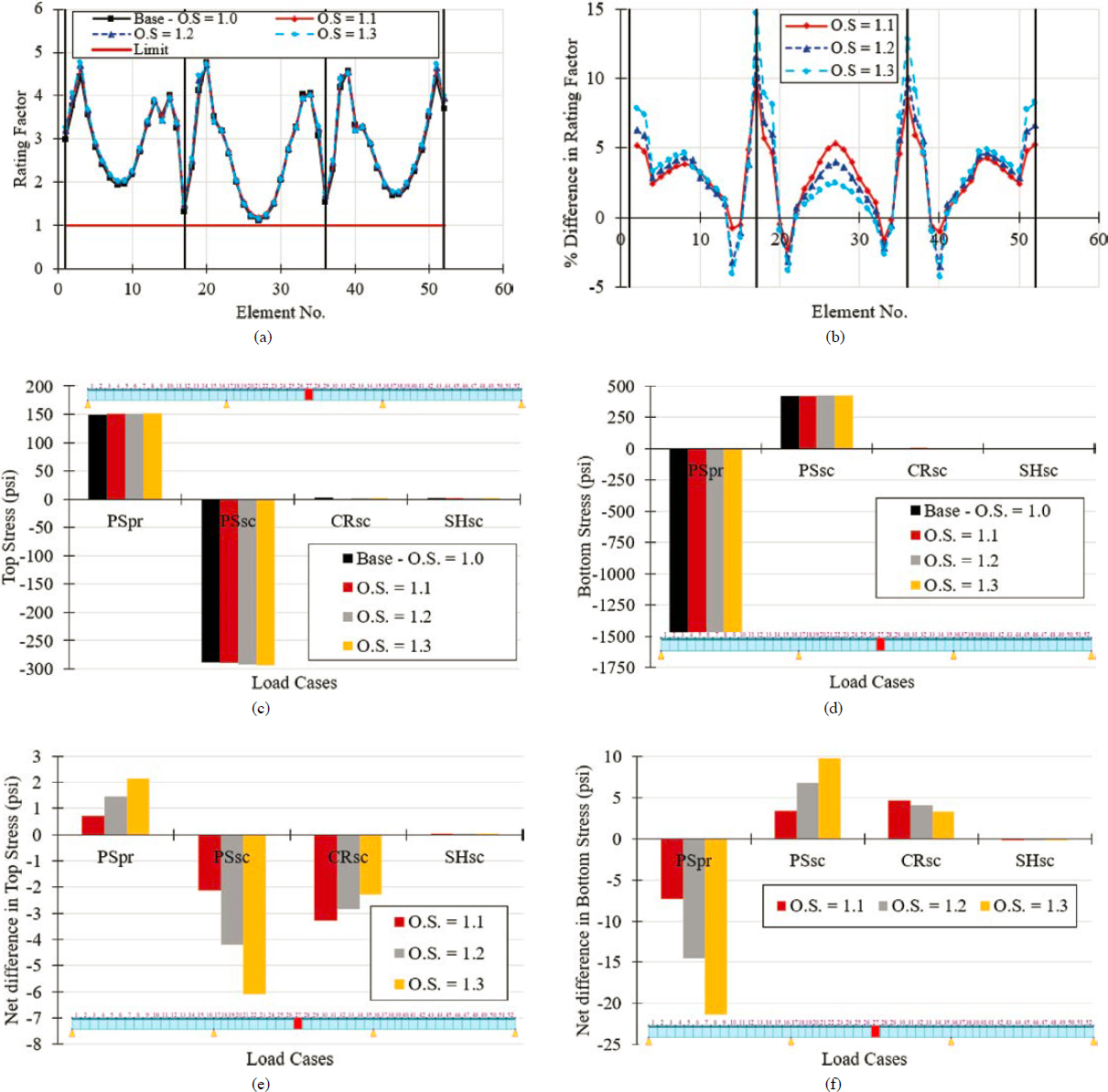

6.4.4.4 Influence of Compressive Strength Overstrength Factors on Load Rating

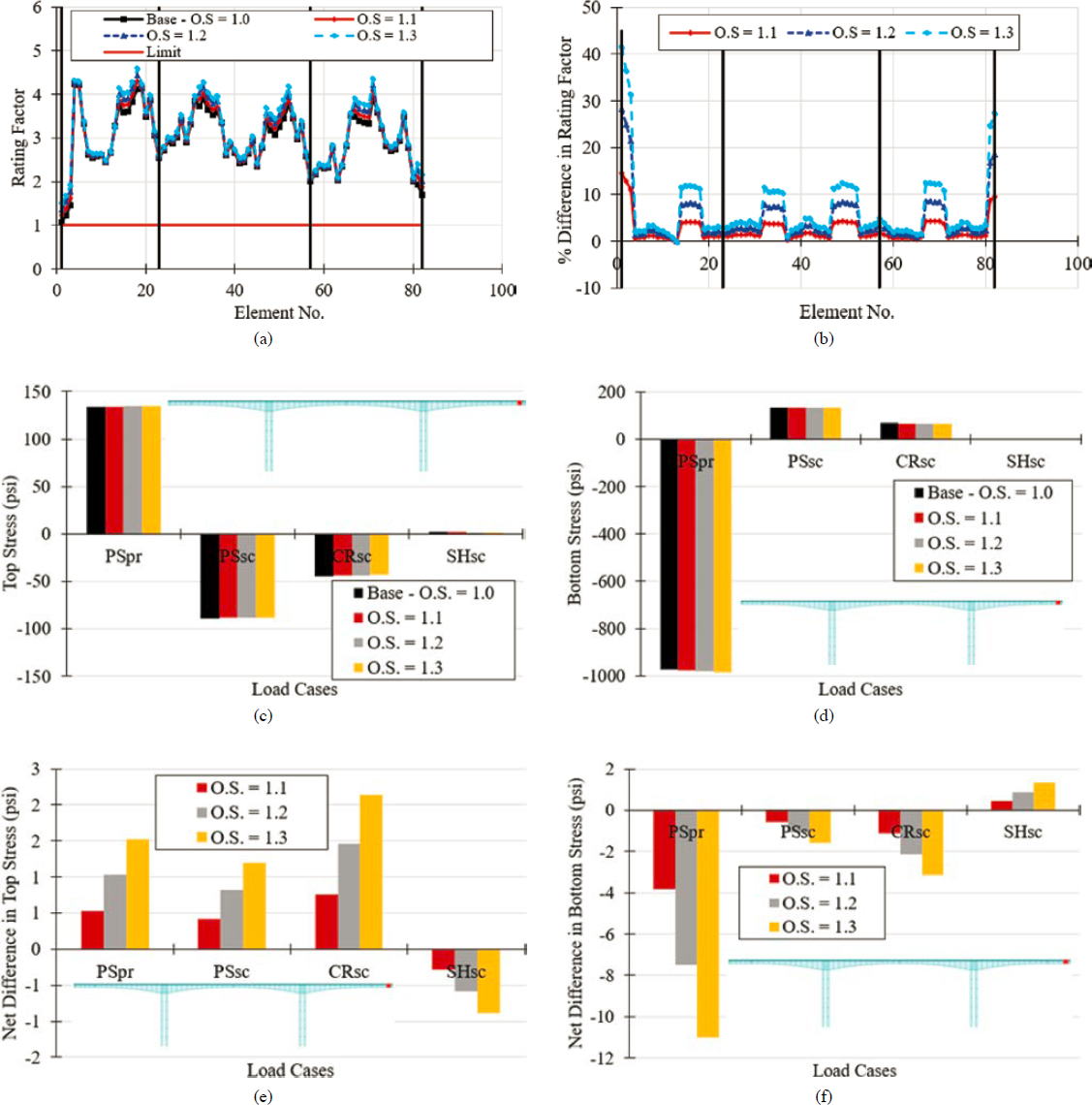

Figure 6-29 shows how the selection of a particular overstrength factor affects load rating. The rating factors in Figure 6-29(a) show the controlling factors for all limit states considered in the longitudinal direction (flexural stress at service, principal tensile stress in the web, flexural strength, and shear strength). A 30% increase in the overstrength factor results in up to a 15% increase in the controlling rating factor [Figure 6-29(b)]. Overstrength factors were applied to the compressive strength of concrete only at 28 days and their influence was considered in the structural analysis as well as in the capacity side. Overstrength strength factors were most impactful when considered in the capacity side at the service limit state since an increase in the specified concrete compressive strength resulted in an increase in the allowable flexural and principal tensile stress. Their influence on time-dependent structural analysis is illustrated in Figure 6-29(c–f) in terms of the top and fiber stress magnitude. The use of overstrength factors resulted in stronger concrete, which creeps less, and results in lower creep-induced prestress losses. This resulted in higher primary and secondary prestressing forces, which resulted in higher stresses. However, this increase was negligible [smaller than 2%, see Figure 6-29(e–f)]. The use of overstrength factors also resulted in smaller stresses caused by secondary creep effects with stronger concretes resulting in lower creep-induced stresses. However, the reduction in top and bottom fiber stresses caused by secondary creep effects was smaller than 6%.

6.4.4.5 Influence of Concrete Strength Development on Load Rating

Figure 6-30(a–c) shows the influence of the predicted variation of compressive strength with time on load rating. Two models were used to predict the variation of compressive strength with time: the CEB-FIP 1990/fib 2010 model and the ACI 209R.92 (ACI 1992) model. For the ACI 209R.92 (ACI 1992) model the parameters (a) for cement type and (b) for curing method were taken as equal to 4 and 0.85, respectively. The CEB-FIP 1990 and fib 2010 models are identical provided that the aggregate factor is assumed to be 1.0 as was done in this case. The functions used to determine the variation of compressive strength with time were used to predict the variation of modulus of elasticity with time. The time-dependent modulus of elasticity was used to determine the effective modulus, which accounted for creep effects. While there was some variation in the predicted strength with time between the two models, this difference diminished after 15 days. The selection of one model or the other was inconsequential when it came to load rating, as the difference in load rating factors was negligible (i.e., smaller than 1%) [Figure 6-30(b–c)].

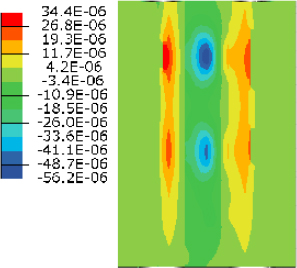

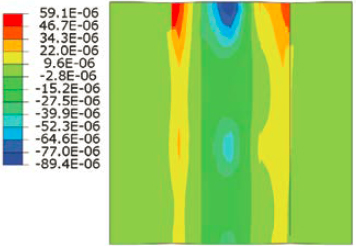

6.4.4.6 Influence of Various Load Cases on Principal Web Tensile Stress and Impact of Assumed Allowable Tensile Stress