Plasma Science: From Fundamental Research to Technological Applications (1995)

Chapter: Introduction and Background

could have a major payoff in reduced-size commercial reactors in the next century.

A detailed theoretical understanding of tokamak turbulent transport from first principles continues to elude us. However, continued development and exploitation of novel diagnostics and experiments, coupled with the new nonlinear numerical simulations, should allow identification of the dominant turbulence drive and damping mechanisms during the next decade. Theoretical understanding of the turbulent transport mechanism should allow the development of new techniques for controlling transport to improve tokamak reactors.

Present experiments have shown that control of the plasma current and electric field (flow shear) profiles can have significant effects on turbulence and confinement. Similarly, optimizing the current profile, pressure profile, and plasma shape are important for increasing the beta limit. However, in many cases present experiments in current profile control have been done with techniques that are inherently transient. They demonstrate the principle, but they are not necessarily sufficient to prove that such profiles can be maintained in steady-state or in long-pulse reactors. The challenge for future experiments will be to demonstrate active control of the plasma current, electric field, and pressure profiles by techniques that are economical and applicable to long-pulse or, preferably, steady-state devices.

EDGE AND DIVERTOR PHYSICS

Introduction and Background

Divertors are magnetically separated regions at the boundaries of magnetic confinement fusion devices. Their originally envisioned functions (Spitzer, 1957) were to exhaust heating power and helium "ash" from fusion reactions and to protect the reacting core plasma from impurities. A separatrix is a surface that separates the flux region of the core plasma from the "burial chamber," the region remote from the core plasma where magnetic field lines intercept material surfaces. The plasma that diffuses across the separatrix from the hot core is "scraped off" on those material surfaces, thus giving rise to the name scrapeoff layer. The edge plasma is located just inside the magnetic separatrix and the

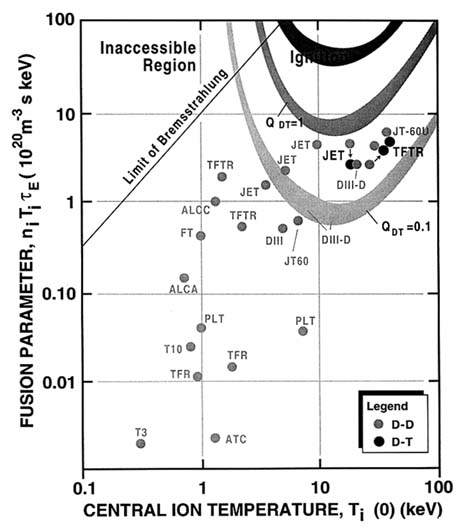

FIGURE 4.2 The approach to power plant conditions of magnetic confinement fusion experiments: The performance of various plasma devices is shown as a function of the "fusion parameter," niTiτE, and the central ion temperature, Ti. The boundaries are indicated for Q = 1 in a deuterium-tritium plasma (i.e., "scientific break-even," where fusion power out equals power in) and for ignition.