A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty (2019)

Chapter: Appendix F: Urban Institute TRIM3 Technical Specification: Using Microsimulation to Assess the Policy Proposals of the National Academies Committee on Reducing Child Poverty

Appendix F

Urban Institute TRIM3 Technical Specification: Using Microsimulation to Assess the Policy Proposals of the National Academies Committee on Reducing Child Poverty

INTRODUCTION

This report describes the work conducted by the Urban Institute in support of the Committee on Building an Agenda to Reduce the Number of Children in Poverty by Half in 10 Years—a committee established by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) in response to a directive in December 2015 legislation. Under contract with the National Academies, Urban Institute staff used the TRIM3 microsimulation model to assess how various policy options could reduce child poverty. Poverty was measured with the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which captures the impact of changes in noncash benefits and tax credits as changes in cash income. Policies were simulated individually and in combination, and results were provided to the committee members showing anti-poverty impacts for all children and for various subgroups of children. Estimates were also provided for the costs of the policy options.

This report describes the methods used for the work and presents key results. The first section describes the TRIM3 model, explains the procedures used to establish baseline simulations and simulate alternative policies, and presents the “baseline” data for this project—a set of simulations of the key transfer and tax programs as of 2015 (the most recent year of simulations available at the start of this work)—and the associated estimates of child poverty. The second section provides details on the modeling of each of the individual policies considered by the Committee, and the third section describes the modeling of packages of policies. Fourth, we describe the methods for applying the policy changes in the context of the

recently enacted tax law changes. The final section sums up and provides some overall caveats for the interpretation of the findings.

THE TRIM3 MODEL AND THE 2015 BASELINE

The estimates for the Committee were developed by applying a comprehensive microsimulation model—the Transfer Income Model, version 3, or TRIM3—to data from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS-ASEC). TRIM3’s computer code applies the rules of government tax and benefit programs to each household in the survey data, either mimicking their real-world operations or simulating hypothetical policy changes. Full documentation of TRIM3 is available on the project’s website, http://trim.urban.org. In this section, we provide a brief overview of the model, describe the aspects of the data preparation that are most relevant to this project, describe the process of creating baseline simulations, and present the results of the 2015 baseline simulations, in terms of both individual programs and child poverty. Lastly, we comment on some recent research regarding the use of microsimulation to adjust survey data for underreporting.

TRIM3 Overview

TRIM3 is a comprehensive microsimulation model of the tax and benefit programs affecting U.S. households. It has been used for over 40 years to support analyses of income support programs—how they operate currently, how they interact, and how changes to these programs can affect families’ economic well-being (Zedlewski and Giannarelli, 2015). The model is funded and copyrighted by the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (HHS/ASPE); the Urban Institute developed the model, and has held a continuous series of contracts to maintain it, augment it to meet new aspects of the policy environment, and use it in support of ASPE analyses. ASPE also allows the Urban Institute to use TRIM3 for other projects such as this one.

TRIM3 is a microsimulation model, which means that its estimates are developed by applying the rules of benefit and tax programs to each of the households in a survey data file, one by one. The model can simulate either the actual rules of programs (“baseline” simulations) or potential alternative policies. When policy changes are modeled, the results might show that a particular family receives more in benefits under an alternative policy than under the baseline. Aggregate impacts are estimated by adding up the individual-level impacts using the “weights” for each person or household.

Several aspects of TRIM3 are particularly important for this analysis:

-

Comprehensiveness: TRIM3 models all the major benefit and tax programs that directly affect the economic well-being of low-income U.S. families. The simulations used in this analysis are:

- Cash benefits: Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF),

- Nutrition benefits: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program,

- Other in-kind benefits and subsidies: Public and subsidized housing, child care subsidies through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), and Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) benefits, and

- Taxes: Payroll taxes, federal income taxes and credits, and state income taxes and credits.

- Detailed modeling: Baseline simulations capture programs in as much detail as feasible, given the limits of the survey data. When policies vary at the state level—in particular for TANF, CCDF, and state income taxes—the state variations are captured in great detail.

- Interactions: TRIM3’s simulations are internally consistent, capturing the interactions that occur across programs. For example, benefits from SSI and TANF are counted as income by the SNAP program, so if a change in SSI or TANF is modeled, the secondary impact of that change on SNAP benefits can also be estimated.

- Ability to capture employment effects: External estimates of how a policy change would affect employment can be applied to the data (e.g., identifying some people to either start or stop working or to work more or less), and benefit and tax programs can be resimulated including the estimated employment changes.

- Flexibility: The system can be used to simulate changes in existing programs and to simulate proposed new programs, such as a national child support assurance system.

CPS-ASEC Data Preparation

The underlying input data file for this analysis was the 2016 CPS-ASEC, which captured families’ demographic characteristics as of Spring 2016 and their incomes and employment status during calendar year 2015. This year of data was the most recent for which a full set of baseline simulations was available at the time the work began. The file includes information on about 185,000 people in 69,000 households. When tabulated using the sampling weights developed by the Census Bureau, the file is statistically representative of the civilian noninstitutionalized population of the United States. (The institutionalized population—including people

in homeless shelters, detention facilities, or residential programs for people with special needs—is not included in the CPS-ASEC and therefore not covered by this analysis.)

The CPS-ASEC provides very detailed information on household demographics, employment, and income. However, the survey is missing some information that is important for simulating benefit and tax programs that affect lower-income families. The two most relevant limitations for this analysis are lack of monthly income data and lack of data on noncitizens’ immigrant status.

Monthly Income Data

Monthly income information is required by the simulations in order to capture the changes that may occur during the year in which a family is eligible for a safety net program and, if they are eligible, the amount for which they are eligible. For example, a family may be eligible for SNAP for the first 4 months of a year when a parent is unemployed, but then lose eligibility once that parent finds employment. If eligibility were assessed using only annual income, the family might incorrectly appear to be eligible for the entire year or ineligible for the entire year.

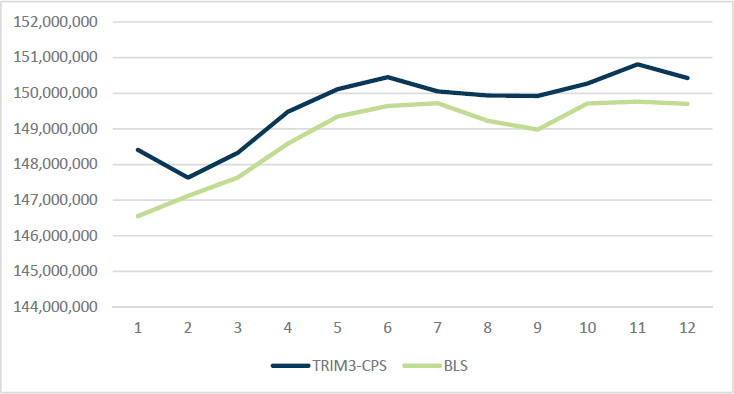

Different methods are used to allocate different types of income across the year, with the most detailed approach taken to allocate earnings and other employment-based income. For individuals who are reported to work fewer than 52 weeks, we first choose a starting-point week and then assign the survey-reported weeks of employment from that point forward (“wrapping” from December to January if needed). The starting point is selected in such a way that the trend in weeks of employment across the months of the calendar year follows the trend from the monthly Bureau of Labor Statistics data (Figure F-1). Similarly, for people who are reported to be unemployed (looking for a job) for part of the year but not the entire year, one or more spells of unemployment is identified (Figure F-2). After the weeks of employment have been identified, earnings are generally assigned evenly across those weeks, implicitly assuming that a person’s weekly earnings are unchanged throughout the year. However, for people who report that they worked part time in some weeks and full time in other weeks, the assignment of weekly earnings reflects those differences.1 Monthly earnings amounts are then generated, treating each month as having 4.333 weeks.

___________________

1 If a person reports usually working full time (35 or more hours per week) but also reports some part-time weeks, we assume he or she works 20 hours per week in the part-time weeks. If a person reports usually working part time, but also reports some full-time weeks, we assume he or she works 40 hours per week in the full-time weeks.

The monthly allocation methods for other types of income are as follows:

- Unemployment compensation: The annual survey-reported unemployment compensation (UC) income amount is generally allocated to all or a subset of a person’s weeks of unemployment, subject to the constraints that UC is not allocated over more weeks than the maximum possible weeks of benefits in a person’s state of residence and that the weekly benefit amount that is assigned falls within the range of minimum and maximum weekly benefit amounts in that state. When people report both UC and earnings during the year, we use state-specific UC rules to estimate a worker’s weekly benefit amount, and that information is also used in the assignment.

- Workers’ compensation: Workers’ compensation is generally divided over all weeks in which a person was either unemployed or out of the labor force; but a portion of recipients are simulated to receive their workers’ compensation as a lump sum.

- Child support and alimony: The number of months over which alimony and child support income amounts are allocated is determined probabilistically based on look-up tables generated from the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Different tables are used for families that do and do not receive TANF; within a subgroup, the probability of a particular number of months of positive child support varies by the annual amount of child support or alimony income, in ranges. Once a number of months is established, the specific months are selected randomly.2

- Other unearned income: Other unearned income amounts—including Social Security, pension income, interest, dividends, rental income, veterans’ payments, regular contributions, educational assistance, black lung/miner benefits, and unspecified “other” income—are allocated evenly across the months of the year.

Note that the above discussion of the monthly allocation of annual values does not mention SSI, TANF, or SNAP amounts, each of which is also reported in the CPS-ASEC in annual terms. Monthly amounts for those programs are developed as part of the baseline simulations, described below.

___________________

2 For people who report both child support and TANF income, and whose annual child support income equals their state’s “pass through” amount times their reported months of TANF income, the months of child support receipt is automatically set equal to the months of reported TANF receipt.

Immigrant Status

The CPS-ASEC asks if people are citizens and, if they are not, asks when they came to the United States. However, the survey does not ask about a noncitizen’s legal status—whether she or he is a lawful permanent resident (LPR), refugee/asylee, temporary resident (e.g., residing in the United States with a student or work visa), or unauthorized immigrant. Whether a noncitizen is potentially eligible for various benefits and for some tax credits depends on his/her specific legal status.

To enable detailed modeling of the program rules regarding immigrant eligibility, an immigrant status is assigned to each noncitizen (Table F-1). The methods follow an approach first developed by Dr. Jeffrey Passel and Dr. Rebecca Clark (1998) and further developed by Dr. Passel and coauthors (Passel, VanHook, and Bean, 2006, Passel and Cohn, 2011). In brief, the approach proceeds as follows:

- Reclassification of some naturalized citizens: Among people who report being naturalized citizens, 1.9 million are reclassified as noncitizens, based on prior analyses indicating overreporting of naturalization.

- Temporary residents: 1.4 million noncitizens are identified as temporary residents, due to having demographic and employment characteristics suggesting that they are in the United States on a work or student visa.

- Refugees/asylees: Noncitizens are initially identified as refugees/asylees if, in the year that they entered the United States, more than one-half of the people arriving from their country of origin were refugees or asylees. Some random adjustments are made to the initial determinations as needed to come closer to externally derived targets. The final results include 1.3 million noncitizens imputed to have had an initial status of refugee or asylee.

TABLE F-1 Key Results of Immigrant Status Imputation Procedures, CY 2015 CPS-TRIM Data

| Group | Imputation result |

|---|---|

| Status Modified from Naturalized Citizen to Noncitizen | 1.9 million |

| Total Noncitizens After Adjustment | 24.9 million |

| Imputed to be Temporary Residents | 1.4 million |

| Imputed to be Refugees/Asylees | 1.3 million |

| Imputed to be LPRs | 11.5 million |

| Imputed to be Unauthorized Noncitizens | 10.7 million |

- Among noncitizens not already identified as refugees/asylees or temporary residents, people are identified as LPRs if they are in an occupation that would require legal status (e.g., police officer) or if they report a type of benefit that would require legal status.

- Among the remaining noncitizens, people are probabilistically assigned to either LPR status or unauthorized immigrant status based on their characteristics, coming acceptably close to a set of externally derived targets for the number and characteristics of unauthorized immigrants in the CPS-ASEC data.

- Adjustments are made as needed to the person-level imputations to ensure logical intrafamily consistency.

Dr. Passel develops the targets that guide the imputation of unauthorized status using numerous sources of data on legal entrants to the United States over time and adjusting those figures to account for age progression, naturalization, emigration, and death; this results in estimates of people in the country legally. The total noncitizens in the CPS-ASEC data minus the number in the country legally provides the estimate of unauthorized immigrants in the CPS-ASEC data. The final imputations include 10.7 million unauthorized immigrants and 11.5 million LPRs.

Baseline Simulation Methods

Before any use of TRIM3 to assess the potential impacts of changes in policies, a set of baseline simulations must first be completed. The baseline simulations apply the actual rules that were in place in the year of the data being used as input to the households in those data. The simulations create new items of information for each household, telling if they are eligible for various programs, their level of tax liability, and so on. Each simulation follows the same steps that an individual would use to compute his or her income taxes or that a caseworker would use to determine a family’s eligibility for benefits. Simulations of benefit programs also identify which of the eligible people or families receive benefits from, and hence participate in the program, in order to create a simulated caseload that comes close to the actual caseload size and characteristics obtained from external administrative and government sources.

In the case of most of the benefit programs discussed here (all except CCDF-funded child care subsidies), the simulated data on program receipt are used to augment, and to some extent replace, the survey-reported CPS-ASEC data on those programs. Specifically, the CPS-ASEC includes annual income and benefit amounts for SSI, TANF, SNAP, and LIHEAP, and includes variables telling whether a household is in public or subsidized housing and whether a family receives benefits from WIC. However, this information is

not sufficient to support modeling of alternative policies, for a few reasons. First, the reported amounts and caseloads fall substantially short of targets, even after missing survey responses have been adjusted through the Census Bureau’s imputation procedures. Second, the survey-reported receipt sometimes does not appear consistent with known program rules. For example, there are cases of families with no young children and no woman of childbearing age who report WIC benefits, or people reporting SSI who are younger than 65 and whose other data show no indications of disability. Third, even when individuals report receiving benefits from a given program appear generally eligible for that program, the specific amounts that are reported are usually not perfectly consistent with what would be computed by applying the program rules to the family’s income and demographic data. That is to be expected, since many respondents probably round various dollar amounts, and since some amounts are imputed by the Census Bureau. However, when alternative policies are modeled, the benefits under the new policy are computed based on the rules and the survey-reported household income and demographic data; it is important that the only difference between the baseline benefit amount and the alternative benefit amount is that resulting from the policy change, and the only way for that to be the case is for the baseline benefits to be computed with the same methods that will be used in modeling the alternative policies.

Although the CPS-ASEC includes questions about benefit receipt, the survey does not ask respondents about their tax liabilities. The Census Bureau imputes federal and state income tax liabilities to the households in the CPS-ASEC as part of their development of SPM poverty estimates, and they make those imputations available to researchers; however, to ensure complete consistency with other simulated data, the TRIM3 analyses use the baseline tax liability amounts modeled within the TRIM3 system.

The baseline simulations are performed sequentially, so that information from one baseline can be used as input to subsequent simulations, creating an internally consistent picture of families’ benefits, tax liabilities, and tax credits. Cash benefits are simulated first, followed by in-kind benefits (which may include cash benefits as part of their income definition). Similarly, federal income taxes are simulated prior to state income taxes, since many states’ income tax systems use information from the federal tax form. Additional key points about the baselines are provided below.

Baseline Simulations of Benefit Programs

In general, the simulations of benefit programs proceed in three steps: determining eligibility, computing potential benefits, and determining which eligible families are enrolled in the program. These steps are performed month-by-month, capturing the fact that a family with part-year work

might be eligible for different benefits during months of employment than during months of unemployment.

The steps in eligibility modeling often include: defining the “filing unit” (the individuals in the household who are considered together in assessing eligibility and benefits); applying immigrant-related restrictions and other restrictions based on demographic characteristics (for example, two-parent families are ineligible for TANF in some states); determining countable income; applying assets tests; and applying income tests. When eligibility policies vary by state, TRIM3 captures the state-by-state variations in eligibility policies with a high degree of detail.

Benefits are computed according to each program’s actual policies. Benefit computation formulas often vary by income levels and other characteristics, but may also be flat amounts (for example, in the case of LIHEAP). In the case of housing and child care subsidies, TRIM3 computes the value of the benefit as an assumed full value of what is being provided minus the family’s required payment. As with eligibility modeling, state-level variations in benefits-related policies are captured in detail. Benefit amounts are computed for all families and individuals who appear to be eligible, including those for whom there is a benefit amount in the public-use data. This ensures that all the baseline benefit data are completely consistent with the known policies and the reported income and family characteristics, which is an important precondition for assessing the impact of policy changes.

The specific methods for determining which eligible families or individuals are enrolled in a program vary across the programs, but similar principles are followed. They are:

- If an eligible person or family reported receiving a benefit in the CPS-ASEC survey (a true report, not an imputed report), that person or family is automatically included in the program’s caseload.

- Among eligible people/families who did not report receipt of a benefit, recipients are selected probabilistically in a way that comes acceptably close to the size and characteristics of the actual caseload—the caseload “targets.” Those targets are derived from administrative data, with adjustments as needed for greater consistency with the TRIM3 universe. (For example, targets for SSI exclude the institutionalized recipients, since the CPS-ASEC surveys only noninstitutionalized households.)

- Probabilistic assignments are made by comparing a potential assistance unit’s estimated probability of enrollment (based on a variety of characteristics, which vary across programs) to a random number. Specifically, if the unit’s probability of participation exceeds the unit’s random number for purposes of participation for this program, the unit is simulated to participate.

- For each benefit program, a unique set of random numbers is used for all probabilistic enrollment assignments for that program for a particular year of data. This ensures that when an alternative simulation results in a change to the unit’s probability of participation, any changes in enrollment decisions are logically consistent with the alternative policy change. For example, assume that a hypothetical policy change increases a unit’s potential TANF benefit, raising the unit’s probability of participation. If the unit participated in TANF in the baseline, the unit will not stop participating; if the probability was previously higher than the random number, the now-higher probability will still be higher than the random number, since the random number did not change. However, if the unit was previously an eligible nonparticipant, the unit may start to participate, if the now-higher probability exceeds the unchanged random number.

- Only families and individuals who are simulated to be eligible for a program are considered as possible program recipients. Because of that assumption, if an ineligible person or family reports a benefit, we implicitly assume that the report was made in error, and that person or family is not included in the simulated caseload. This simplification avoids complications that would arise from applying policy changes to a simulated baseline caseload that included ineligible participants.3

Details of the methods for each simulation are available on the TRIM3 project’s website (http://trim3.urban.org). Here, we summarize key points and note some challenges involved in modeling each program.

- SSI:

- Portion of program modeled: Benefits to individuals in households (not institutionalized).

- Timeframe: Monthly

- Policies: Primarily national-level; state-level supplement amounts are obtained from a combination of national and state-level sources.

___________________

3 Future model development could consider some allowance for technically ineligible units being in the caseload, based on administrative estimates of the extent of that type of enrollment error. However, this would require decisions regarding how to handle these cases in alternative simulations. (For example, if an ineligible unit that has been included in the caseload is modeled to receive higher earnings due to a minimum wage increase, it is unclear whether it would be more appropriate to continue to include the unit in the caseload, or whether to assume the unit would lose benefits due to exceeding the eligibility limit by an even greater amount.)

-

- Eligibility and benefits challenges: Assessing potential eligibility based on age (65 or older) is straightforward, but assessing potential eligibility based on disability is complex. For adults, disability is inferred through a combination of the survey-reported reason for not working and survey-reported disability income. Disability cannot be assessed for children.

- Caseload selection: For adults, the caseload is aligned to targets by reason for eligibility (age vs. disability), type of unit (single or couple), state, and citizenship status. For children, after identifying children whose parents report them as SSI recipients, the rest of the caseload is randomly selected from among children in income-eligible families, to reach targets by family structure (two-parent, single-parent, no-parent) and by state. We also come close to the number of children in multiple-recipient households (about 500,000), according to analysis by the Government Accountability Office (Government Accountability Office, 2016).

- TANF:

- Portion of program modeled: TRIM3 models cash aid provided through TANF and Separate State Program (SSP) funds. The model also identifies benefits paid through Solely State Funded (SSF) programs; those are separately classified as SSF, not TANF.

- Timeframe: Monthly

- Policies: Almost entirely state-level; source of rules is the Welfare Rules Database (for the 2015 policies, see Cohen et al., 2016).

- Eligibility and benefits challenges: The data do not allow us to directly assess if a family that appears eligible may in fact be ineligible due to previously having reached a time limit. A portion of otherwise-eligible families are treated as ineligible due to time limits, in order to reach estimated state-level targets for time-limited families; the targets are derived from administrative data. Also, the families simulated to be eligible nonparticipants include some who have been excluded due to failure to meet program requirements. Benefits are computed based on family characteristics and detailed state policies, but they do not incorporate the impact of either special-needs payments (additional payments in some states for reasons such as the start of the school year, pregnancy, or a special hardship) or monetary sanctions (reductions of benefits for failure to comply with a requirement).

- Caseload selection: For the TANF/SSP caseload, key targets include type of unit (single-parent units with and without

-

- earnings, two-parent units, and child-only units by various reasons for child-only status), state, and presence of noncitizens. An underlying participation function also incorporates varying probabilities of participation by other characteristics, including level of potential benefit, race/ethnicity, and number and ages of children. There is no single source for SSF targets; SSF targets are derived from caseload-reduction reports submitted to the federal government and from various state data systems and reports.

- CCDF:

- Portion of program modeled: Children subsidized through CCDF funds. (States may combine other funds with CCDF funds to serve more children; however, the baselines for this analysis identify only the children viewed by Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Families as served by CCDF funds.)

- Timeframe: Monthly

- Policies: Almost entirely state-level; source of rules is the CCDF Policies Database (for 2015 policies, see Stevens et al., 2016).

- Eligibility and benefits challenges: In some cases, the family’s required copayment depends in part on the hours that the children require care; that is inferred based on the mother’s usual hours of work. The model treats all months of the year the same, without any special treatment of the summer months.

- Caseload selection: The key target is the average monthly number of children served, by state. Probabilities vary by age of child, single-parent vs. two-parent families, and relative income levels. The simulation also takes into account the survey-reported amount of child care expenses; to the extent feasible, eligible families whose simulated copayment is similar to what they reported spending in child care expense have a higher likelihood of being included in the simulated caseload, and eligible families whose simulated copayment is quite different from what they reported spending (e.g., we simulate that their copayment would be $50/month, but they reported spending $3,600 across the year) have a lower likelihood of being included in the simulated caseload.

- Public and subsidized housing:

- Portion of program modeled: Public housing and vouchers for obtaining rental housing.

- Timeframe: Monthly

- Policies: The same policies are applied nationally for the definition of income and the computation of each assisted

-

- household’s required rent. Fair Market Rents (FMRs) are obtained from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and vary by county and metropolitan area.

- Eligibility and benefits challenges: Because eligibility policies may vary from one Public Housing Authority to another, baseline simulations do not explicitly model eligibility beyond requiring that household income be below 80 percent of area median income. However, among households reported to be in public or subsidized housing in the CPS-ASEC data, required rents are estimated based on the national-level formulas and the household’s income, and each assisted household’s subsidy value is estimated as the appropriate FMR (based on the county or metropolitan area and the needed apartment size) minus the required rent.

- Caseload selection: Unlike other simulated benefit programs, the public and subsidized housing simulation does not include a participation function or alignment to external targets. Among households reported to be in public or subsidized housing in the CPS-ASEC data, if the required rent is less than the assumed FMR (based on location and estimated number of bedrooms), the household is treated as enrolled. If the required rent is greater than the assumed FMR, the household is treated as though it is not in public or subsidized housing.

- SNAP:

- Portion of program modeled: All recipients except those who are homeless or in institutions.

- Timeframe: Monthly

- Policies: Policies are obtained from the Food and Nutrition Service (FNS); some state-level variations are obtained from the SNAP State Options Report (Food and Nutrition Service, 2016) and other sources.

- Eligibility and benefits challenges: Estimates of SNAP eligibility are very sensitive to assumptions about which members of complex households would jointly file for SNAP. The TRIM3 methods follow the explicit rules about which family members are required to file for SNAP together and make assumptions about other situations.

- Caseload selection: The key enrollment targets include family structure, presence of cash benefits (SSI or TANF), level of potential SNAP benefit, presence of earnings, state, and citizenship status.

-

WIC:

- Portion of program modeled: Benefits to infants, their mothers, and young children. (Benefits to pregnant women are captured only to the extent that a childless woman of childbearing age reports WIC in the CPS-ASEC.)

- Timeframe: Monthly

- Policies: Policies are obtained from FNS data. Basic policies are national, but there is state variation in the value of the benefit and in the certification period for children.

- Eligibility and benefits challenges: The WIC program does not explicitly define whose income is counted in determining eligibility; we assume that the eligibility process considers all people related to the children, including both parents in the case of unmarried couples.4 One aspect of WIC eligibility—nutritional risk—cannot be observed in the CPS data. The simulation assumes that all people who pass the demographic and financial eligibility tests are at nutritional risk.

- Caseload selection: For infants and children, enrollment is aligned to state-level targets.

- LIHEAP:

- Portion of program modeled: Heating and cooling help (weatherization help is not modeled).

- Timeframe: Annual

- Policies: State-specific eligibility policies are obtained from the LIHEAP Clearinghouse website (https://liheapch.acf.hhs.gov). Because most LIHEAP benefits are provided in the winter, based on eligibility determination in the fall, the simulation uses the eligibility policies in place in the fall of the calendar year; specifically, the CY 2015 LIHEAP eligibility simulation used the FY 2016 eligibility policies (which went into effect in October 2015).

- Eligibility and benefits challenges: Local programs may differ in their income definitions or the period over which they assess income, at the point that a household applies for help; we assume all places use annual income.

- Caseload selection: The simulated caseload is aligned to state-specific targets, which are estimates of the unduplicated count of households receiving heating and/or cooling help over that calendar year.

___________________

4 The WIC eligibility estimates produced for the Food and Nutrition Service (Trippe et al., 2018) also use a broad definition of the economic unit. If eligibility was estimated with a narrower unit—considering related subfamilies as separate units—more children would be identified as eligible.

Baseline Simulations of Tax Programs

The simulations of taxes require the identification of the tax unit and then the computation of the tax amounts. People are assumed to pay all the taxes that they owe, and with only a few exceptions they are assumed to take all available tax credits; therefore, the modeling of taxes does not involve alignment to caseload targets in the same way as the modeling of benefits does. However, modeling of income taxes does require additional imputations to estimate items of information not available in the CPS-ASEC data. Key aspects of the tax simulations are:

- Payroll taxes:

- Portion of program modeled: Old age, survivors, disability, and health insurance taxes (OASDHI); includes taxes on self-employment earnings and Civil Service Retirement Service (CSRS) contributions.

- Timeframe: Annual

- Policies: Social Security website

- Federal income taxes:

- Portion of program modeled: Most aspects of individual income tax computation. Some tax features that are applicable only to very high-income taxpayers or very rare situations are not modeled.

- Timeframe: Annual

- Policies: 1040 (and supporting schedule) forms and instructions

- Imputations preceding the modeling: Data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Statistics of Income Public Use File are used to impute amounts of itemized deductions, capital gains/losses, and individual retirement account (IRA) contributions.

- Alignment of usage of selected credits: In general, taxpayers are assumed to take all credits for which they appear eligible. However, the modeling of the child and dependent care expense credit assumes that a portion of the units who appear eligible—based on having working parents, children under age 13, and child care expenses—do not in fact take the credit for some reason (for example, because they are ineligible due to their flexible-spending-account benefits). The take-up of the credit is aligned to data on the actual number of tax units taking the credit.

- State income taxes:

- Portion of program modeled: Most aspects of states’ individual income tax computation. Some tax features that are applicable only to very high-income taxpayers or very rare situations are not modeled.

-

- Timeframe: Annual

- Policies: State-by-state tax rules compiled by a team led by Dr. Jon Bakija, Williams College

2015 Baseline Simulation Results vs. Targets

The 2015 simulations of benefit programs were, in almost all cases, very successful at meeting administrative targets. As discussed above, these simulations generally select a simulated caseload from among the households that appear to be eligible in order to meet overall caseload targets (shown in Table F-2) as well as subgroup targets. The simulation of taxes differs from the simulation of benefits in that there is almost no alignment involved. Instead, the results are determined almost entirely by applying the tax rules to the survey data. Results are then compared to administrative data for validation purposes, but overall results are not aligned to come closer to those targets. The result of the TRIM3 baseline simulations is a data file that comes as close as feasible to capturing the real-world incidence and amounts of benefits and taxes in 2015 (Table F-3).

Benefit Program Simulations Compared with Targets

For SSI, TANF, LIHEAP, and CCDF-funded child care subsidies, the simulated caseloads and aggregate benefits all come very close to administrative data figures. For each of these programs, the simulated caseload and the simulated aggregate benefits are no more than 3 percent from total national targets. In addition, the simulations come very close to the actual distribution of the caseload in terms of state of residence and key demographic characteristics. The aggregate amounts of simulated benefits exceed the amounts according to the survey data (including both truly reported amounts and amounts imputed by the Census Bureau) by 11 percent in the case of SSI, 69 percent in the case of TANF, and 56 percent in the case of LIHEAP. (CCDF-funded child care subsidies are not reported in the survey.)

In the case of SNAP, the simulated caseload is very close to the actual figure, but simulated aggregate benefits fall short of the amount, according to administrative data, by 8.5 percent. This pattern of falling short of target for aggregate benefits while hitting the target for the simulated caseload is consistent with other baseline years. TRIM3 finds fewer units eligible for high benefits than are observed in administrative data, and it makes up for the shortfall by exceeding the target for units eligible for lower benefits. The shortfall in high-benefit units is not unique to TRIM3 and is also observed in eligibility estimates produced by Mathematica Policy Research for the FNS. Despite the shortfall in dollars relative to the administrative data, the simulated aggregate SNAP benefit amount of $63.0 billion is much closer

TABLE F-2 TRIM3-Simulated Benefit and Tax Data versus Targets, 2015

| Counts of Persons or Units are in Thousands; Dollar Amounts are in Millions | CPS-ASEC Reported Dataa | TRIM-Simulated | 2015 Admin. Datab | TRIM as % of Admin. Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSI (Noninstitutionalized)c | ||||

| Adults with SSI During Year for Self or Child | 6,414 | — | — | — |

| Avg. Monthly Adult Recipients (Persons) | — | 7,103 | 6,958 | 102.1% |

| Avg. Monthly Child Recipients | — | 1,234 | 1,254 | 98.5% |

| Annual Benefitsd | $50,715 | $56,399 | $55,569 | 101.5% |

| TANFe | ||||

| Avg. Monthly Caseload (Families)f | 800 | 1,325 | 1,326 | 99.9% |

| Annual Benefits | $3,931 | $6,646 | $6,462 | 102.8% |

| SNAPg | ||||

| Avg. Monthly Units (Households)f | 12,245 | 22,367 | 22,404 | 99.8% |

| Annual Benefits | $36,602 | $63,039 | $68,859 | 91.5% |

| Public and Subsidized Housing | ||||

| Ever-subsidized Householdsh | 5,760 | 5,165 | 4,635 | 111.4% |

| Annual Value of Subsidy | na | $36,955 | na | — |

| LIHEAPi | ||||

| Assisted Households | 4,205 | 6,747 | 6,748 | 100.0% |

| Annual Benefits | $1,717 | $2,673 | 2,675 | 100.0% |

| WIC | ||||

| Families With Any Benefits | 3,780 | 4,071 | na | — |

| Avg. Monthly Recipients, Infants/Children | na | 5,861 | 5,891 | 99.5% |

| Avg. Monthly Recipients, Womenj | na | 907 | 1,865 | 48.6% |

| Annual Value of Benefit, Pre-rebatek | na | $4,875 | na | — |

| CCDF-funded Child Care Subsidies | ||||

| Avg. Monthly Families with CCDF Subsidy | na | 834 | 840 | 99.4% |

| Avg. Monthly Children with CCDF Subsidy | na | 1,351 | 1,387 | 97.4% |

| Aggregate Value of Subsidy | na | $6,611 | $6,585 | 100.4% |

| Counts of Persons or Units are in Thousands; Dollar Amounts are in Millions | CPS-ASEC Reported Dataa | TRIM-Simulated | 2015 Admin. Datab | TRIM as % of Admin. Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payroll tax | ||||

| Workers Subject to OASDI Tax | na | 157,185 | 168,899 | 93.1% |

| Taxable Earnings for OASDI | na | $6,748,090 | $6,395,360 | 105.5% |

| Taxes Paid by Workers (OASDI + HI) | na | $560,877 | $541,055 | 103.7% |

| Federal Income Taxes | ||||

| Number of Positive Tax Returns | na | 104,461 | 99,022 | 105.5% |

| Total Tax Liability, Positive Tax Returns | na | $1,312,511 | 1,435,849 | 91.4% |

| Earned Income Tax Credit | ||||

| Returns with Credit | na | 19,712 | 28,082 | 70.2% |

| Total Credit | na | $41,770 | $68,525 | 61.0% |

| State Income Taxes | ||||

| Number of Positive Tax Returns | na | 89,970 | na | — |

| Taxes Paid, Net of Creditsl | na | $318,089 | $340,468 | 93.4% |

NOTE: na = not available; avg. = average; admin. = administrative.

a CPS-ASEC reported data included the data that are “allocated” by the Census Bureau in cases of nonresponse. Items not asked in the survey that are imputed by the Census Bureau (such as tax liabilities) are not shown.

b Administrative figures are adjusted or combined for consistency with simulation concepts. In particular, fiscal year administrative data are adjusted for greater comparability with calendar year simulated data, and benefits paid to individuals in the territories are excluded. Benefits include both federally-funded and state-funded amounts.

c SSI figures include state supplements.

d Administrative data for SSI include retroactive payments, which are approximately 9 percent of total payments; TRIM does not simulate retroactive payments.

e Includes benefits funded by federal TANF money and separate state programs, but not solely state-funded programs. The administrative figure for aggregate benefits is computed as the average per unit benefit from administrative microdata applied to the actual caseload.

f For TANF and SNAP, an average monthly caseload is computed using the CPS-reported number of months that benefits are received.

g The administrative figures for SNAP exclude SNAP disaster assistance.

h Administrative figure is the number of occupied public and assisted units.

i An exact unduplicated number of assisted households is not available; an unduplicated count is estimated using estimates of the overlap between groups receiving heating, cooling, and crisis benefits.

j Benefits to pregnant women are not captured in the TRIM simulation.

k The TRIM benefit amount includes the pre-rebate value of infant formula. An administrative figure for WIC food costs net of the rebate was not available.

l The actual state income tax amount is from the Census Bureau’s Annual Survey of State Government Tax Collections, which reflects tax collections during a fiscal year; TRIM3’s figures are estimates of tax liability during the tax year.

TABLE F-3 TRIM3 Benefits and Expenses Incorporated into the 2015 SPM

| SPM Benefit or Expense | Notes |

|---|---|

| SSI | TRIM3 SSI amounts are used instead of the reported amounts. |

| TANF | TRIM3 TANF amounts are used instead of the reported amounts. |

| SNAP | TRIM3 SNAP amounts are used instead of the reported amounts. |

| WIC | TRIM3 simulated amounts are used instead of the Census Bureau values assigned to people who report WIC receipt in the CPS ASEC. |

| LIHEAP | TRIM3 simulated amounts are used instead of reported amounts. |

| Public and Subsidized Housing | Uses TRIM3 public and subsidized housing subsidies rather than amounts imputed by the Census Bureau to households reporting receipt of public and subsidized housing assistance. TRIM3 follows the Census Bureau SPM methodology of capping the amount of the subsidy counted for the SPM at the share of the SPM threshold representing shelter and utility expenses, less the household’s required rental payment. |

| Child Care Expenses | Primarily reflects CPS reported amount. However, for families simulated by TRIM3 to receive CCDF child care subsidies, reflects the required copayment amount. Child care expenses are counted as an expense in the SPM. |

| Payroll Taxes | TRIM3 simulated amounts are used instead of Census Bureau simulated amounts. |

| Realized Capital Gains/Loss | Statistically matched from the IRS Public Use File as part of the federal income tax baseline. The Census Bureau tax model does not impute capital gains and so they are not included in the Census Bureau SPM. However, capital gains are included in the TRIM3 SPM because they are included in the calculation of TRIM3 federal and state income taxes.a |

| Federal Income Tax | TRIM3 simulated amounts are used instead of Census Bureau simulated amounts. Includes taxes on capital gains (not included in the Census Bureau estimate). Includes refundable credits (EITC and Additional Child Tax Credit). |

| State Income Tax | TRIM3 baseline simulated amounts are used instead of Census Bureau simulated amounts. Includes taxes on capital gains. Includes refundable credits. Replaces Census Bureau simulated amounts. |

a Capital gains are obtained through a statistical match with the IRS Public Use File as part of the TRIM3 federal income tax baseline.

to the actual figure ($68.9 billion) than the amount captured in the survey data ($36.6 billion).

In the case of public and subsidized housing, TRIM3 includes any households living in public or subsidized housing according to the public-use survey data as long as their income is below 80 percent of the area median income published by HUD and their required rent payment would be lower than the HUD Fair Market Rent based on the number of bedrooms estimated for the household and their county or metropolitan area; these methods overshoot by about 11 percent the number of households in public housing or with housing vouchers for low-income families funded by HUD, probably because some of the identified households are receiving other types of housing help.

The WIC simulation comes very close to targets for the number of infants and children with WIC. However, the simulation is only able to capture WIC receipt by women who are the mothers of infants; benefits received by pregnant women are not fully captured because the CPS does not identify pregnancy.

Tax Simulations Compared with Targets

In simulating payroll taxes, the number of workers observed as subject to OASDI taxes is about 7 percent short of the actual figure. However, the aggregate taxable earnings seen in the data and the resulting simulated payroll taxes are somewhat higher than the administrative data target. This pattern of falling short of the target for the number of workers who are subject to OASDI taxes while exceeding the total amount of taxes is consistent with other baseline years and is driven by reported employment and earnings in the CPS-ASEC. A contributing factor to the excess in OASDI taxes is that CPS-ASEC respondents are likely to report their full earnings, rather than their earnings less nontaxable components such as pretax health insurance premium payments and contributions to medical and dependent care flexible benefits plans. Such reductions to earnings are not captured in the baseline simulation.

The federal income tax simulation counts a number of tax returns with positive income tax liability that is 5.5 percent higher than the actual number of returns for tax year 2015, but the model falls short of the actual amount of tax liability on positive-tax returns by 8.6 percent. The shortfall in taxes is likely due to the CPS-ASEC not capturing all the income in the highest portion of the income distribution. The same issue is observed in the simulation of state income taxes, which identifies an aggregate amount of state income liability that is 6.6 percent below the aggregate target.

The simulation also falls short in the identification of units with the EITC. The shortfall in simulated EITC is not unique to TRIM3 and is commonly observed in other microsimulation estimates based on CPS-ASEC

data. Some of the shortfall is explained by the fact that TRIM3 does not model noncompliance with EITC rules. CPS-ASEC data issues may also contribute to the shortfall (Wheaton and Stevens, 2016). TRIM3 assigns EITC to all units found eligible according to the CPS-ASEC data. Assigning additional units to receive the EITC would require modeling noncompliant receipt of the EITC or adjusting the earnings and family composition data in the CPS-ASEC, both of which are beyond the scope of this study.

To validate the TRIM3 SPM calculations, we first calculate the SPM following the Census Bureau methodology using unadjusted CPS-ASEC variables and Census Bureau imputed variables obtained from the Census Bureau’s SPM research file.5 We then substitute TRIM3 variables for the CPS ASEC and Census Bureau imputed variables and compare the effects of the TRIM3 variables on the estimates.

The estimates presented here are comparable with the Census Bureau’s revised 2015 SPM estimates that are included in the Census Bureau’s 2016 SPM report (Fox, 2017). In preparing the 2016 SPM, the Census Bureau revised the EITC, housing subsidy, and work-related expense imputations. For consistency, the Census Bureau re-issued estimates for 2015, using the same methodology, and included the results in the 2016 SPM report. We use the revised 2015 variables for our estimates.

When we use the TRIM3 model to calculate SPM poverty using only the CPS-ASEC and the Census Bureau imputed values, we find that 12.038 million children were in SPM poverty in 2015, compared with 12.026 million according to the Census Bureau (Table F-4).6 Small differences such as this arise because our calculated results are generated using public-use data rather than internal Census Bureau files and because certain household heads younger than 18 who are living with parents are classified as “children” when calculating the SPM threshold in our calculated results, but not in the published results.7

___________________

5 See Fox (2017) for discussion of the Census Bureau’s methods. The SPM research file is available at the Census Bureau’s website at: https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2015/demo/supplemental-poverty-measure/spm.html.

6 See appendix table A-1 of Fox (2017).

7 The change in the number of children results from TRIM3’s restructuring of “inverted households” in the TRIM3 conversion process. These households are ones in which a teen or young adult is reported to be the household reference person, despite having one or both parents present. Many of these households involve immigrants, and it is likely that the teen or young adult was selected as the reference person because of his/her English capability. TRIM3 reorganizes the inverted households, so that a parent is the household reference person. If the teen is under the age of 18, reclassifying the teen from “head” to “child” increases the number of children in the unit, thus affecting the SPM poverty threshold. If the teen is working, then reclassification as a “child” also affects the unit’s work expenses, as the SPM methodology does not assign work expenses to children under the age of 18 unless they are the head or spouse of the SPM unit.

TABLE F-4 Effect of TRIM3 Adjustments on SPM Child Poverty and Deep Poverty Estimates, 2015

| Children in Poverty | Children in Deep Poverty | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (1,000s) | Percent | Total (1,000s) | Percent | |

| Census Bureau (Published) | 12,026 | 16.2% | 3,628 | 4.9% |

| Census Bureau (Calculated) | 12,038 | 16.3% | 3,636 | 4.9% |

| TRIM3 Adjustments: | ||||

| Correction for Underreportinga | ||||

| SSI | 11,462 | 15.5% | 3,388 | 4.6% |

| + TANF | 11,205 | 15.1% | 3,138 | 4.2% |

| + SNAP | 9,502 | 12.8% | 2,081 | 2.8% |

| + WIC | 9,362 | 12.6% | 2,081 | 2.8% |

| + LIHEAP | 9,324 | 12.6% | 2,076 | 2.8% |

| Other TRIM3 Adjustmentsb | ||||

| + Housing | 9,295 | 12.5% | 2,078 | 2.8% |

| + Child Care Expenses | 9,378 | 12.7% | 2,106 | 2.8% |

| + Taxes and Tax Credits | 9,633 | 13.0% | 2,136 | 2.9% |

a The “correction for underreporting” rows show the effects of replacing the CPS ASEC amounts with TRIM3-simulated variables that correct for underreporting. First, TRIM3-simulated SSI is substituted for reported SSI. Starting from that simulation, TRIM3-simulated TANF is then substituted for reported TANF, and so-on. TRIM3 child support income adjustments are incorporated at the same time as TANF.

b The “other TRIM3 adjustments” rows show the effects of replacing the CPS ASEC amounts (obtained from the Census Bureau’s SPM research file) with TRIM3-simulated variables. Starting from the correction for underreporting simulation that includes LIHEAP, TRIM3-simulated housing subsidies are substituted for the Census Bureau imputed subsidies. Next, TRIM3 child care expenses are substituted for the Census Bureau amounts. Finally, TRIM3 payroll taxes, federal income taxes and credits, and state income taxes and credits are substituted for the Census Bureau values. TRIM3 imputed realized capital gains (and loss) are incorporated at the same time as taxes.

SOURCES: Published Census Bureau estimates are from Fox (2017), Appendix Table A-1. Other estimates are obtained from TRIM3 tabulations of the 2016 CPS ASEC.

We next show the incremental effects of substituting TRIM3 variables for the CPS-ASEC and Census Bureau variables in the poverty calculation, focusing first on TRIM3 correction for underreporting of SSI, TANF, SNAP, WIC, and LIHEAP, and then describing the effects of incorporating other TRIM3 variables. We find that substituting TRIM3-simulated SSI income into the Census Bureau SPM poverty definition lowers the estimated SPM child poverty rate from 16.3 percent to 15.5 percent. If we keep the TRIM3-simulated SSI in the SPM definition and next substitute TRIM3-simulated TANF for the CPS-reported amount, the child poverty rate drops from 15.5 percent to 15.1 percent. Replacing CPS-reported SNAP with TRIM3-simulated SNAP decreases the estimated child poverty rate from 15.1 percent to 12.8 percent. Replacing the Census Bureau’s

WIC value with TRIM3-simulated WIC decreases the child poverty estimate slightly—from 12.8 percent to 12.6. Replacing reported LIHEAP with TRIM3-simulated LIHEAP has little effect on the estimated number of children in poverty. Taken together, the TRIM3 adjustments for underreporting reduce the estimated SPM child poverty rate from 16.3 percent to 12.6 percent.

The remaining rows in Table F-4 show the effects on the SPM poverty estimate as other TRIM3 adjustments (housing subsidies, child care expenses, and taxes) are incorporated into the SPM definition. As noted previously, these adjustments do not replace reported variables but instead replace values imputed by the Census Bureau. They are typically included in TRIM3 poverty estimates and analyses to preserve internal consistency between simulated programs and between baseline and alternative policy scenarios.

Incorporating TRIM3 housing subsidies into the SPM estimate that includes TRIM3 correction for underreporting reduces the estimated child poverty rate by 0.1 percentage points. Incorporating TRIM3 child care expenses into the SPM increases the estimated child poverty rate by 0.2 percentage points.8 Substituting TRIM3 taxes and tax credits for the Census Bureau amounts and incorporating TRIM3-imputed realized capital gains and losses increases the child poverty rate 0.3 percentage points.9 Taken together, the TRIM3 corrections for underreporting and other TRIM3 adjustments reduce the child poverty rate from 16.3 percent to 13.0 percent.

The TRIM3 adjustments also affect the deep poverty rate—the share of children below one-half of the poverty threshold. Correction for underreporting reduces the estimated deep poverty rate from 4.9 percent to 2.8 percent for children. Incorporating TRIM3 housing subsidies, child care expenses, and taxes and tax credits has little effect on the deep poverty rate, increasing it by 0.1 percent.

Note that although TRIM3 adjusts for the underreporting of several key elements of family resources, other elements of resources—which may

___________________

8 The TRIM3 SPM estimate allows higher expenses for some families because it does not cap child care expenses (combined with other work-related expenses) at the earnings of the lower earning spouse or partner. As noted previously, TRIM3 does restrict the expenses to parents/guardians who work or are in school. In some cases, the simulated child care copayment may be higher than the reported CPS amount.

9 One reason that the poverty rate increases when the Census Bureau’s tax amounts are replaced with TRIM3-simulated amounts is that the Census Bureau EITC assignment does not prevent unauthorized immigrants from receiving the EITC. Under federal income tax rules, the tax unit head, spouse, and qualifying child must each have a valid Social Security number to claim the EITC. In the absence of this restriction, the TRIM3 SPM child poverty rate would have been 12.3 percent in 2015 (not shown). Thus, if TRIM3 did not deny the EITC to unauthorized immigrants, substituting TRIM3-simulated taxes and tax credits for Census Bureau amounts would have lowered, rather than raised, the SPM child poverty rate.

also be underreported—are used as they appear in the public-use survey data. Rothbaum (2015) compares CPS-ASEC income amounts to aggregates from the National Income and Product Accounts and finds that the CPS-ASEC data for 2012 captured only 72 percent of interest income, 66 percent of unemployment compensation, 60 percent of self-employment income, 28 percent of workers’ compensation income, and 68 percent of total pension income, among other findings. Some poor children are affected by these income amounts. For example, in the CY 2015 CPS-ASEC data used for this analysis, 12 percent of children in SPM poverty (according to our baseline measure) lived in an SPM unit with some self-employment income, and 2 percent lived in a unit with some type of pension income. (These figures include both truly reported amounts and amounts imputed by the Census Bureau when responses are not provided.) To the extent that income amounts that are not adjusted by TRIM3 are underreported by families with children, our estimates of children’s poverty could be overstated.

On the other hand, some of the data imputations made by the Census Bureau could be leading us to identify as nonpoor some children who might be poor. For example, while only 8 percent of poor children live in SPM families that truly reported interest or dividend income (compared with 27 percent of all children), the Census Bureau’s procedures to “allocate” (fill in) missing data increase that percentage to 24 (compared to 62 percent for all children). Regarding the most common type of income—earnings—research by Bollinger and colleagues (forthcoming) finds that when the Census Bureau imputes amounts of earnings due to nonresponse, the imputed figures are biased upward for low earners (and downward for very high earners). If Census Bureau data imputations are assigning too much income of certain types to low-income families with children, that would operate in the direction of understating child poverty.

Critique of TRIM3 Poverty Estimates

Two recent studies have examined the effect on poverty of TRIM3 SNAP adjustments relative to poverty estimates based on survey data combined with linked SNAP administrative case-level data (Mittag, 2016; Stevens, Fox, and Heggeness, 2018). The studies conclude that TRIM3 overassigns benefits to low-income households, thus underestimating the poverty rate.

This finding contradicts our own distributional comparisons, which find that TRIM3 underassigns benefits to the lowest income households. In 2015 we find that 8 percent of TRIM3 SNAP participating units with children had $0 in monthly gross income, compared with 13 percent according

to the SNAP Quality Control Data (QC).10 Twenty-two percent of participating units with children had monthly gross income above $2,000, compared with 12 percent according to the QC. TRIM3’s underassignment of SNAP to the lowest income households stems from an apparent shortfall of such households in the survey data.

A possible explanation for these apparently contradictory results is that the linked data analyses take the survey income data as “truth” when examining the distribution of SNAP households by income level. However, survey income may be misreported or imputed by the Census Bureau for nonresponse. In addition, household composition at the time of the survey may not be the same as household composition at the time benefits are received. These factors may distort the true relationship of income and SNAP benefits when benefits obtained from linked administrative data are compared with survey income.

In contrast, TRIM3 assigns SNAP benefits that are consistent with the income and household composition in the survey data, whether these data are accurately or inaccurately reported or imputed by the Census Bureau for nonresponse. Assigning baseline benefits consistently with the income and household composition in the survey data enables alternative simulations that modify program rule parameters to generate internally consistent results. Such consistency is critical for the types of analyses performed in this report.

While analysis of linked administrative data offers opportunities for insights to improve microsimulation, further research is needed before final conclusions can be reached as to the over- or underestimation of poverty in TRIM3.

POLICY CHANGES TO REDUCE CHILD POVERTY

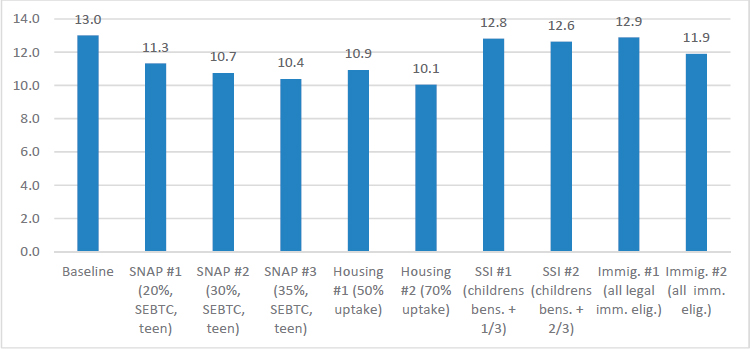

Under this project, alternative policies were modeled in 11 different policy areas: the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), child care expenses, the minimum wage, an employment program, SNAP, housing subsidies, SSI, child allowances, child support assurance, immigrant eligibility for safety-net benefits, and a basic income guarantee. For each policy area, two or more variations of the policies were simulated. After each simulation, children’s SPM poverty was computed using the modified data.

The impact of each policy is estimated by comparing the alternative policy’s results—in terms of child SPM poverty as well as program costs and caseloads—to the baseline results. To capture secondary impacts, the full sequence of benefit and tax programs was modeled for each policy. For example, if earnings increase due to a minimum wage change, the family

___________________

10 The SNAP QC estimates are obtained from table A.3 in Gray, Fisher, and Lauffer (2016).

could become eligible for lower TANF and SNAP benefits; could have to pay higher contributions toward subsidized housing or subsidized child care; would owe higher payroll taxes; and would likely see a change in federal or state income tax liability or tax credits.11

This chapter first reviews assumptions used throughout the simulations, regarding program participation, family expenditures, and employment and earnings impacts. We also summarize some strengths and limitations of these approach. The remainder of the chapter then describes, for each policy area, the specific methods and assumptions used to simulate that option—both the explicit policy changes and any assumed changes in employment status or hours of work. Results are also briefly described.

This work builds on prior work by TRIM3 project staff to assess the anti-poverty impacts of policy changes, individually and as a package. See Giannarelli, Morton, and Wheaton (2007) and Lippold (2015) for projects assessing how policy changes could reduce poverty across the entire population and Giannarelli and colleagues (2015) for a prior project examining the potential for policies to reduce child poverty.

OVERVIEW OF SIMULATION ASSUMPTIONS

Assumptions needed to be made about the extent to which the policy changes would change families’ behavior in three areas: program participation, expenditures that impact the SPM, and employment or hours of work. A decision also needed to be made regarding the modeling of benefit programs with fixed budgets.

Program Participation Decisions

Regarding program participation, one type of change happens automatically: If a family becomes ineligible for a program, it stops receiving the benefit. However, assumptions are needed for the treatment of families who become eligible for a different benefit amount due to the policy change or who become newly eligible. We made the simplifying assumption that a family already receiving benefits from a program before the policy change (in the baseline simulation) would continue to participate in the program even if its benefit fell; although in reality a family might decide to stop participating due to a drop in potential benefit, modeling that type

___________________

11 This analysis does not pick up any impacts on a family’s SPM poverty level due to changes in medical out-of-pocket spending. Those expenses could be affected by changes in Medicaid or CHIP eligibility or enrollment, enrollment in employer-sponsored health insurance, or eligibility for or use of health insurance exchanges and associated tax credits. Also, this analysis did not capture changes in eligibility for free or reduced-priced school meals.

of change would complicate the interpretation of the simulation results. In the case when a policy change causes a family to become newly eligible for a program, the model’s internal participation methods were generally used to estimate whether or not that family would begin to receive the benefit. Some specific assumptions regarding the program participation decisions are discussed in the sections on the individual policies.

A change in participation in one program can have secondary impacts on other programs or types of income. For example, because SNAP recipients are eligible for WIC even if their income is higher than the WIC eligibility estimates, a change in SNAP enrollment status can affect a family’s WIC eligibility. Also, because most states’ TANF programs retain all or a portion of the child support paid to TANF recipients, a change in whether a family receives TANF can also change its child support income.

Family Expenditure Decisions

Two key types of expenses affect the program simulations and the SPM poverty calculations and housing and child care expenses. The modeling assumes that changes in a family’s income—for example, higher earnings due to a minimum wage increase—do not result in the family moving to a different apartment or child care provider. Like the assumption of constant program participation behavior, this ensures that simulated changes in a family’s economic well-being are closely tied to the modeled policy change. Of course, for a family with a housing subsidy or child care subsidy, the required rental payment or copayment could change when income changes, and those changes are modeled.

In the case of child care, the one type of behavioral change that may be modeled is the imputation of new child care expenses for some parents who are modeled to start working. When that possibility is modeled, previously estimated equations are used to estimate the probability that a newly working family will need to pay for nonparental care, and if so, the amount of the child care expense. The equations are calibrated so that, when applied to all the families in the CY 2015 CPS-ASEC data, they approximate the incidence and amount of child care expenses reported in the CPS-ASEC data, overall and by income group. The equations predict that the majority of low-income working families do not have any nonparental child care costs, consistent with what is reported in the survey.

Two other categories of expenses that affect the SPM poverty calculation—out-of-pocket medical expenses and child support payments (when a member of the family is paying child support to someone living elsewhere)—are treated as constant across the simulations. The model is not programmed to estimate changes in out-of-pocket health spending due to the types of programmatic or income changes modeled in this project,

and it is not currently able to estimate how income or employment changes could affect a noncustodial parent’s payment of child support.

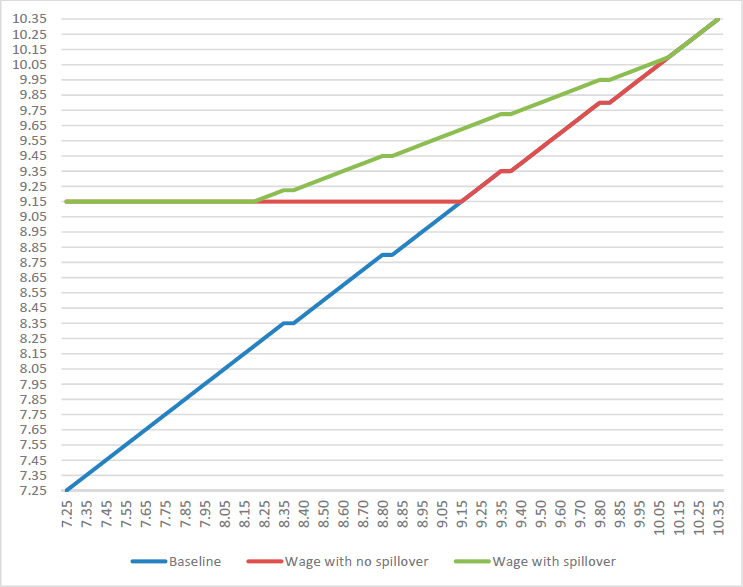

Employment and Earnings Changes

Changes in whether individuals were employed and in their hours of work were implemented for almost all the simulations, based on specifications provided by the Committee. These types of changes sometimes involved numeric “targets” for people to start working or stop working, based on the Committee’s interpretation of the available econometric evidence. In those cases, the specific people to start or stop working were randomly selected from among those people affected by the policy. In other cases, reductions or increases in hours of work per week were specified for everyone affected by a policy in a certain way. (Details for each policy area are described below.)

Note that the employment and earnings effects were not explicitly restricted to poor families with children. Depending on the specific policy and how the employment and earnings changes were defined and implemented, those changes might have affected nonpoor families, or in some cases might have affected families without children. For example, a minimum wage increase affects low-wage workers even if they live in higher-income families and/or families with children. As another example, EITC employment and earnings changes were restricted to families affected by the EITC changes, meaning that their earnings were low enough to be eligible for the EITC, although only a portion of these individuals are poor. Unless otherwise noted, employment and earnings changes discussed in this Appendix include all of the individuals for whom these changes are modeled, without restriction to poor or low-income families with children.

Changes in employment were assumed to affect unemployment compensation and workers’ compensation in some cases. Specifically, if a person selected to start working had either unemployment compensation or workers’ compensation, that income was assumed to change to $0 due to the new job. In the case of people selected to stop working, unemployment compensation benefits were added only in the case of job loss due to minimum wage increases. In all other simulations with reductions in employment, the job loss was assumed to be voluntary, meaning that no unemployment compensation would be paid.

In all cases, the assumed changes in employment, earnings, and/or other incomes were imposed for the duration of the policy simulation, so that all the simulations of benefit and tax programs for that policy option would consistently treat the person as having the modified employment/earnings/income data. For example, if a person who starts working was previously eligible for safety-net benefits, the levels of potential benefits may decline,

or he or she might become ineligible for some of the benefits. A new worker might be modeled to start to have child care expenses; but might also become eligible for child care subsidies.

Changes in employment status also affect a person’s estimated level of work expenses other than child care. Following the Census Bureau’s SPM methods, a family’s resources are offset by $40.07 for each week that an adult has earnings to reflect spending on transportation and other work expenses (other than child care). For example, if a mother is simulated to move from no work during the year to 52 weeks of work due to one of the policies, the increase to her resources due to the new earnings is offset by $2,084 for purposes of the SPM calculation; conversely, if a mother is simulated to stop working, the reduction to her resources is partially offset by the fact that she is no longer treated as having those work-related expenses. These changes somewhat mitigate the changes in poverty status produced by changes in employment status.

Programs with Fixed Funding

A final issue regarding the simulation assumptions concerns the modeled benefit programs that operate with fixed amounts of funding: LIHEAP, WIC, TANF, and CCDF-funded child care subsidies. The above procedures resulted in some changes to the simulated total benefits costs of these programs as a secondary impact of other policy changes. We did not attempt to recalibrate caseloads or benefits to hold spending constant.

Strengths and Limitations of this Approach

The use of this type of microsimulation modeling allows us to consider the impacts of the potential policies using consistent methods and a consistent metric—the Supplemental Poverty Measure—for all policies. In effect, microsimulation allows us to “try out” the policies using data on a representative sample of the U.S. population. Given the characteristics of the input data and the assumptions described above, the TRIM3 computer code can compute what would happen to a particular family’s economic resources under a proposed policy. The simulations capture not only the direct impacts of policies but also the secondary impacts—for example, the fact that an increase in a child’s SSI benefit could affect the family’s SNAP benefit, since SSI is considered cash income in determining SNAP eligibility and benefits. These calculations are all simulated by the model’s computer code with as much accuracy as possible, given our understanding of the policies and the limitations of the input data.

Of course, there are limitations to these approaches. One overall limitation is the uncertainty in the modeling of behavioral changes, and in

particular in the modeling of employment and earnings changes. As discussed above, this analysis imposed employment and earnings changes specified by the members of the Committee. Another overall limitation is that TRIM3 focuses on the year represented by the input data; it does not currently include the ability to age the population into the future and to capture how the policy changes could affect individuals in successive years, within the broader context of a changing population and economy. Focusing on this particular analysis, other limitations include the fact that the “baseline” data represent 2015, and the fact that mechanisms to pay for the new policies were not modeled.

Because of these issues, it is quite possible that, even if one of the Committee’s policies were put into place exactly as described here, the actual anti-poverty impact could differ from the impact modeled here. However, we do not have a quantitative estimate of the extent of this potential deviation. Looking back at past TRIM3 analyses of the anti-poverty impacts of potential policies, it is almost never the case that a simulated policy is enacted exactly as it was modeled, and without any other policy changes or economic changes occurring at the same time.12

Nevertheless, within the assumptions and population data used for this analysis—in the terminology of economics, “all else equal”—microsimulation modeling provides a way to assess the anti-poverty impacts of the different policies, using the same data, computation mechanisms, and assessment metrics for each one.

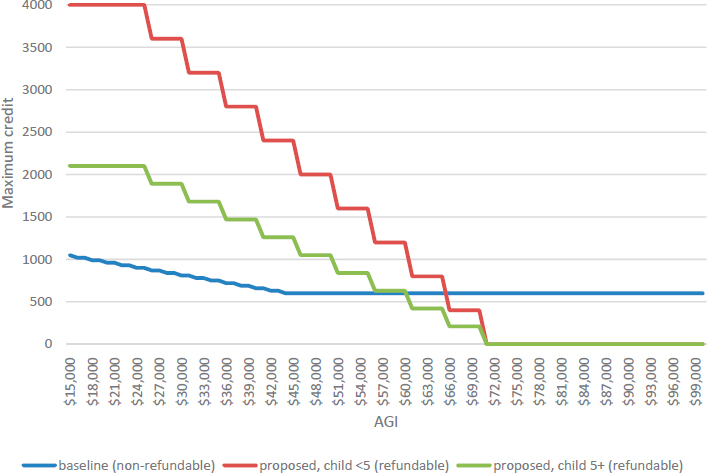

EITC

The Committee requested exploratory analysis of several changes to the EITC in the federal income tax system. The two options selected for final analysis were these:

- EITC #1: An expansion of the phase-in range of the EITC, based on a proposal from the Children’s Defense Fund (Children’s Defense Fund, 2015).

- EITC #2: A 40 percent increase in both the credit rate and the phase-out rate.

___________________

12 For example, Zedlewski and colleagues (1996) estimated that the federal welfare reform legislation proposed in early summer of 1996 would increase the number of poor children by 1.1 million. In fact, child poverty declined in the years following welfare reform. However, a major driver of the estimated increase in children’s poverty was the expected loss of food stamps by immigrant children; instead, the year following the passage of the initial legislation, a subsequent bill restored benefits for immigrant children who were living in the United States at the time that the first law was enacted. Also, the late 1990s saw very high levels of GDP growth, which was not foreseen or accounted for by the 1996 modeling.

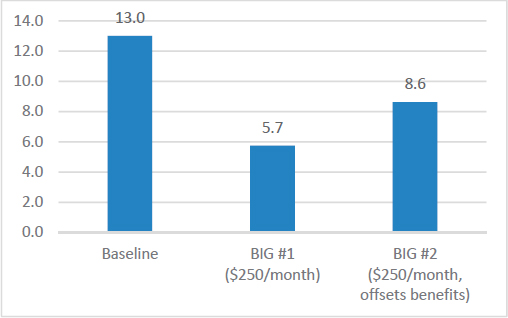

EITC Policy: Implementation Assumptions