Translating Knowledge of Foundational Drivers of Obesity into Practice: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2023)

Chapter: 11 Progress in Obesity Solutions That Relate to Political, Economic, and Environmental Systems

The second session of the October workshop addressed progress in obesity solutions that relate to political, economic, and environmental systems. Sara J. Czaja, professor of gerontology and director of the Center on Aging and Behavioral Research in the Division of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, and Heather D’Angelo, program director at the National Cancer Institute in the Health Communication and Informatics Research Branch within the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), co-moderated the session. Three speakers participated in a panel addressing political and economic systems, and two speakers discussed environmental systems. The session ended with a panel and audience discussion with the five speakers.

POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC SYSTEMS

Jamie F. Chriqui, senior associate dean and professor of health policy and administration in the School of Public Health at the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) and director of health policy research for the UIC Institute for Health Research and Policy, discussed obesity prevention policies. She described them as upstream, population-level strategies for effecting changes to environments, communities, and behaviors. Examples at the national level include nutrition labeling of food packages and restaurant menu items, as well as the federal child nutrition programs and their governing nutrition standards (e.g., for school meals). Many school-based policies are at the state level, Chriqui noted, as exemplified by policies that govern nutrition education and physical education in schools, state laws that govern

taxation, and complete streets policies. Local-level policies, she continued, may be at the county, municipal, school district, or other local level, and are the most proximal to on-the-ground implementation. An example is land use policies, which can affect the types of food outlets permitted in a community and whether sidewalks or transit systems are present.

Chriqui observed that physical activity–related policies tend to exist at the local and state levels, whereas food and nutrition policies often exist at the national level. She asserted that assessment of progress in obesity prevention policies requires considering actions on both sides of the energy balance equation, referencing an Institute of Medicine report that presents an ecological framework highlighting the range of sectors involved in each side (IOM, 2012).

According to Chriqui, measuring policies involves consideration of policy adoption, change, implementation, and effects (i.e., impact). She explained that the choice of measures for evaluating policy adoption and policy change depends on the policy’s jurisdiction. The measurement process is relatively easy at the federal level, she submitted, because typically it is necessary to evaluate only one or two laws or regulations. Policy surveillance, she explained, entails studying variability in policies at the state and local levels across the country and examining what is in statute compared with what is being implemented and its impact.

Chriqui pointed out that the politically fraught nature of policy creates challenges for policy adoption and implementation. She suggested that policy implementation is a critical but often overlooked component of measuring policy impact. Accordingly, she appealed for measures of policy implementation to capture both whether a policy is being implemented and how (e.g., equitably or not) and whether implementation is being sustained over time.

Touching briefly on policy effects, Chriqui pointed to the importance of examining both proximal and distal outcomes. As an example of a proximal outcome, she cited changes in access to nutritious foods or a safe place to be active; as an example of a distal outcome, she cited a change in health outcomes, such as chronic disease incidence. She called for starting with evaluation of enacted policies, because “what gets measured gets changed,” and understanding and measuring the implementation and impact of existing policies can provide insight into why they are or are not working as intended.

Chriqui concluded by elaborating on evaluation of policy implementation, which she said benefits from mixed-methods (i.e., both quantitative and qualitative) approaches, such as interviews with key stakeholder interviews. NIH has been at the forefront of advocating for implementation science theories, methods, and frameworks, she remarked, focusing to date on clinical trials and clinical interventions. Other theoretical approaches from

implementation science that can be applied to evaluating policy implementation and its effects include the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance/sustainment) framework, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, and the implementation outcomes framework.1

Jason Block, associate professor and director of research in the Department of Population Medicine at Harvard Medical School and the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, discussed the politics of obesity prevention, appropriate outcomes to measure in policy evaluation, and study designs for evaluating obesity prevention policies. Obesity prevention policies are often highly politically fraught and perceived as exemplifying a “nanny” state, he observed, and he submitted that these aspects of such policies have resulted in the U.S. approach to obesity prevention being characterized by enactment of single, “one-off” policies, such as taxation strategies within individual municipalities, rather than comprehensive programs and coordinated strategies. Block contrasted this approach with that of Mexico or Chile, both of which he said have been more comprehensive in implementing obesity prevention initiatives. A challenge with a piecemeal approach like that of the United States, he suggested, is that it limits the ability to evaluate a policy’s impact, particularly whether it produced the robust effects that many public health experts believe are needed to lead to meaningful population-level change. Block also explained that policy evaluations are difficult to carry out because most policies are enacted at the state or municipal level, and limited data are available for both before and after they have been implemented.

Block continued by noting that, despite the desire to demonstrate effects of obesity prevention policies with hard outcomes, such policies are not intended or structured to decrease obesity prevalence at the national level in the United States. Rather, he maintained, their relatively small intended effects are expected to reduce obesity incidence and help mitigate rise in obesity prevalence over time. This distinction is difficult to communicate, he acknowledged, and it also complicates what success looks like.

Block pointed out that obesity prevention policies often target proximal outcomes such as dietary intake or quality, whose measurement is more feasible to measure on the time horizon and with the type of data typically available for policy evaluation compared with more distal policy effects. A key question, suggested Block, is whether it is fair to require a policy to demonstrate effects on (relatively distal) health outcomes instead

___________________

1 For more information on these frameworks: RE-AIM framework (https://re-aim.org/learn/what-is-re-aim/); Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (https://cfirguide.org/); and implementation outcomes framework (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7) (accessed January 5, 2023).

of the proximal outcomes that are more directly linked to the policy. Data from electronic health records can potentially support assessment of both proximal and health outcome effects, he suggested, but their potential to serve these purposes is limited by health care fragmentation and lack of data for the full range of geographic areas in which policies of interest are implemented. Block added that, if available, these data would enable comparative evaluations. He noted further that cost-effectiveness analyses can also be used to assess health outcome effects, but are often viewed with skepticism.

Block offered a few comments on study designs for evaluating obesity prevention policies. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are usually not an option, he pointed out, particularly for national- or state-level policies. RCTs in virtual settings are possible, he remarked, but have some limitations in their application to the real world. Block reported that evaluations of nutrition policies have used interrupted time series and natural experiment approaches, which he suggested are well suited, despite their own limitations, for evaluation of obesity prevention policies.

James Krieger, executive director of Healthy Food America and clinical professor at the University of Washington School of Public Health and School of Medicine, maintained that progress in obesity can be measured in many ways that do not involve distal health outcomes such as body mass index (BMI). He shared his views on what progress in obesity prevention looks like from the perspective of policy makers, advocates, and community members, framing his comments around seven dimensions of progress to consider.

The first dimension Krieger cited is identifying policies that are effective as well as those that are not. The definition of effectiveness on the ground can vary among interest groups, which he explained results in multiple dimensions or measures of effectiveness for a given policy. Using Seattle’s sugary drink tax as an example, Krieger recalled that policy makers viewed the tax as making progress in terms of raising revenues that were invested in marginalized communities, not necessarily in terms of its effect on BMI or obesity.

Krieger identified as a second dimension of progress implementing policies that address upstream causes of obesity. He posited that if upstream causes can be mitigated or eliminated, downstream factors can be expected to change and ultimately contribute to a decline in obesity rates. He suggested thinking of this as a logic model or causal model approach to policy evaluation (e.g., Figure 7-1). If such factors as corporate behaviors (e.g., as measured by a 2022 Access to Nutrition Initiative report); power imbalances between Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) and White individuals or between low- and high-income communities; and structural racism are deemed contributors to obesity, he reasoned, then it is important to have metrics that can assess positive changes in those upstream factors (e.g., standards for corporate behavior developed by the Corporate Racial

Equity Alliance) as measures of progress in obesity prevention (Access to Nutrition Initiative, 2022; Corporate Racial Equity Alliance, 2022).

Krieger moved on to a third dimension of progress—scaling effective policies. A measure of progress could be to assess the reach of an effective policy and determine which populations are benefiting. Going even further, an effect size could be included and multiplied by the reach to produce the effect impact, which Krieger said could indicate whether a policy’s impact is growing.

As a fourth dimension, Krieger cited identifying and mitigating unintended and negative consequences of obesity policies. He gave weight stigma as an example of such consequences.

A fifth dimension, Krieger continued, is optimizing cobenefits. For instance, an obesity policy might have potential to improve overall diet quality or build community capacity to enact and implement future policy change. Krieger contended that including these components of policy evaluation could broaden the concept of what is meant by progress in obesity prevention.

A sixth dimension, Krieger said, is the use of efficient, effective, and just approaches to policy adoption and implementation and assessment of whether equitable policy adoption and implementation are increasing. He defined “equitable” as meaning that a policy advances racial equity and social justice, engages impacted communities in policy development, and builds their capacity and power to create positive community change. He presented an illustration of a spectrum of community engagement to ownership (Figure 11-1), which he suggested can help in assessing the degree to which communities are able to participate in and lead policy implementation.

The seventh and final dimension Krieger identified was applying an equity lens to policy adoption, implementation, and evaluation. Applying

SOURCE: Presented by James Krieger, October 25, 2022. Gonzalez and Facilitating Power (2019). Reprinted with permission.

an equity lens, he clarified, is a process that entails analyzing or diagnosing the impact of a policy’s design and implementation on underserved and marginalized individuals and groups. An increase in equity-centered policies would constitute progress, he explained, which is why a policy’s differential impacts by race, income level, or intersectional identities are often measured in assessing its equity impact (University Policy Library, 2022). Achieving equity is also a process, Krieger maintained, which he said makes it important to assess the proportion of policies that explicitly include equity impact in their legislative language, and to evaluate the extent and meaningfulness of community engagement and partnerships (e.g., whether true power sharing and joint decision making are in effect).

Krieger concluded by emphasizing that communicating progress is important for building and sustaining momentum. Relevant channels and outputs include policy briefs for elected officials and media pitching to secure coverage and presentation of results in the community that participated in the research.

ENVIRONMENTAL SYSTEMS

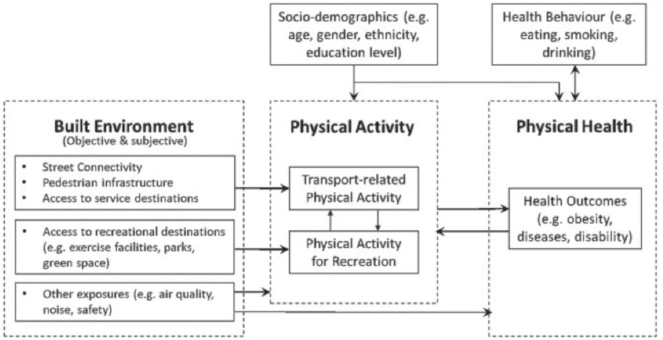

Carlos Crespo, dean of the College of Applied Health Sciences and professor of kinesiology and nutrition at the University of Illinois Chicago, discussed social environments, built environments, and findings from The Guide to Community Preventive Services (The Community Guide) with respect to promotion of physical activity. He shared a conceptual model (Figure 11-2) to illustrate interactions among sociodemographic factors, built environments, physical activity, and physical health.

SOURCE: Presented by Carlos Crespo, October 25, 2022. Song et al. (2020). Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Because social and environmental systems, along with health behaviors, influence obesity, Crespo explained, any single policy or measure will fail to capture the full picture. A similar web of influences exists, he maintained, for physical activity—one important aspect of energy balance—such that manipulating certain aspects of social environments and systems, for example, can affect physical activity positively or negatively. Social environments at the neighborhood level have been examined for their impact on physical activity, he elaborated, listing examples of neighborhood and community characteristics—such as crime and safety, social cohesion and social capital, sense of place, and disorder and incivilities—that can be measured and assessed in terms of their influence on physical activity (Kepper et al., 2019). Interpersonal and individual characteristics, he added, also influence a person’s level of physical activity.

Crespo turned to discussing built environments—comprising housing, food systems, natural environments, transportation networks, and neighborhood design—which he emphasized impact health and health behaviors for better or for worse (CDC, 2011). He elaborated on four elements of built environment systems—transportation, land use, service facilities, and urban design—and provided examples of measurable factors within those elements that could be used to assess progress in obesity solutions.

As examples for transportation, Crespo listed bike facilities, walk-ability, street connectivity, public transit stations, and urban greenways. For land use, he mentioned green open space (i.e., land suitable for being physically active), population density, and diversity of mixed-use space (i.e., where people can feel comfortable walking). For service facilities, he cited shops and stores, recreation and fitness facilities, and food markets. Lastly, examples of urban design included neighborhood design, urban sprawl, and urban renewal projects. Crespo also listed additional, more subjective factors that might affect one’s willingness to be physically active: cleanliness, harmony and variety of buildings, condition of individual buildings, potentially dangerous sites, greenery and plantings, parks and open space, streetscapes, signage, lighting, traffic, and parking.

Next, Crespo described a systematic review and report to the Community Preventive Services Task Force on the effectiveness at promoting and increasing physical activity of built environment approaches that combine transportation system interventions with land use and environmental design (Community Guide, 2017). The final list of articles included in the review examined three types of interventions: park-based, greenway and trails, and urban greening. Some interventions provided only infrastructure, Crespo explained, whereas others included additional intervention components (e.g., adding programming at park facilities, extending park hours, and advertising park improvements). He highlighted findings of the review indicating that great opportunities exist to leverage transportation to

increase physical activity, which Crespo submitted might be because many people move from a point A to a point B daily and could do so via active transportation.

The report to the Community Preventive Services Task Force recommended park, trail, and greenway infrastructure interventions combined with additional interventions, such as structured programs or community awareness, to increase physical activity. Crespo relayed what he called “very impressive” findings from the systematic review: interventions led to an 18.3 percent median increase in the number of people who used parks, trails, or greenways and a 17 percent median increase in the number of people who used them to engage in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. The review found further, he reported, that built environment approaches combining new or enhanced transportation systems (e.g., pedestrian or cycling paths) with new or enhanced land design (e.g., access to a public park) were effective in promoting physical activity. The combination of built and social environment factors, Crespo said in summary, impacts the capacity to be physically active.

Kristine Madsen, professor at the University of California, Berkeley School of Public Health, began her presentation on food environments by sharing an upbeat advertisement with a catchy musical score. She pointed out that the ad, which was created for a leading soft drink brand, is like many other ads for food and beverage products that are intended to appeal to people’s emotions. They evoke thoughts of family, friends, fun, love, happiness, sex, power, boldness, and success, she elaborated, which give rise to desires that draw people toward the advertised products. This increasingly pervasive and provocative food media environment seeps into one’s consciousness in meaningful ways, Madsen added, more so than most public health efforts to raise awareness and promote behavior change.

Madsen identified food availability and portion sizes as other important aspects of the food environment. Five times as many items exist in grocery stores today than in the 1990s, she observed, and 20,000 new packaged foods and beverages are introduced each year (Ruhlman, 2017; USDA Economic Research Service, 2021). She reported further that sizable increases have occurred over the past several decades in the number of large-portion product introductions, and fast food sales have increased dramatically during the same timeframe as fast food outlets have proliferated (Statista, 2022; Young and Nestle, 2012). Food is available in a multitude of settings and often marketed in a way that encourages impulse buying, Madsen said, and adding to the challenge is a reportedly higher cost of healthier compared with less healthy diets (Rao et al., 2013).

Madsen noted that measures intended to counterbalance these powerful food environment cues include, for example, food package and menu labeling, which she described as helpful but “tiny compared to the onslaught

in the food environment” that promotes excess consumption of unhealthy foods. She echoed Block’s earlier assertion that dramatic shifts in the rise of obesity and diabetes are due to environmental changes, and that a multifaceted approach to countering these environmental changes will be necessary. As an example of such an approach, she pointed to the decline in cigarette smoking and eventually in lung cancer deaths that occurred in the wake of multiple legislative successes, including tobacco taxes, smoke-free restaurant and workplace policies, warning labels, and advertising bans (American Cancer Society, 2017; CDC, 2021). Measuring progress in the food environment is a critical part of measuring progress in obesity, she contended, and she then turned to discussing two major approaches that have been taken to modifying food environments and how those approaches have been measured.

The first of those approaches is taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages, which Madsen reported have been implemented in about 50 countries. Key measures of interest, she explained, include change in price, change in volume sold, change in product availability, and change in calories and/or grams of sugar in taxed products as a result of reformulation. Most U.S. taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages, she noted, are excise taxes in cents per ounce, and distributors pay the local jurisdiction based on the number of ounces sold. About 70 percent of these taxes are passed through to consumers, she reported. Madsen added that if demand is viewed as a function of price, the price elasticity of demand is a helpful measure. This measure has been calculated for the Americas: a 1.0 percent increase in price is associated with a 1.4 percent decrease in demand (Pan American Health Organization, 2020). Madsen translated that figure to posit that U.S. taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages have reduced demand by about 20 percent, which she called a “huge effect size” that reflects major population-wide behavior changes (Powell et al., 2021).

Tax structure makes a difference, Madsen asserted, sharing an example from the United Kingdom’s tiered tax on sugar-sweetened beverages. Beverages with <5 grams of sugar per 100 ml were not taxed, and the tax on beverages with 5–8 grams of sugar per 100 ml (tier 1) was lower than that on beverages with >8 grams of sugar per 100 ml (tier 2). Madsen reported that the number of products in tier 2 decreased notably when the tax was announced and implemented, which effectively changed the physical food environment (Dixon et al., 2021).

A commonly raised question about those taxes, Madsen said, is whether other sweet beverages are substituted and offset the tax’s expected health impact. Current evidence suggests no substitution or only modest substitution of other sweet products that are not taxed, she reported, such as 100 percent juice and flavored milk (Leider et al., 2021; Lozano-Rojas and Carlin, 2022; Pell et al., 2021). With regard to a similar question about

substitution of foods with sugary or salty snacks, she stated that evidence shows either no substitution or some substitution, but a less than 20 percent offset of the tax’s effect on total sugars sold.

Madsen then identified front-of-package labels as a second major approach to modifying food environments. She characterized these labels as catering to system 1 thinking, which she described as fast, habitual, and driven by emotion (Roberto et al., 2021). She contrasted these labels with traditional back-of-package nutrition labels that people read when engaged in system 2 thinking, which she termed a slow and deliberate process (Roberto et al., 2021). Key measures of the impact of front-of-package labeling, Madsen noted, include demand (i.e., effect of the labels on specific nutrition parameters they highlight), product availability, and product reformulation. Studies of the effectiveness of front-of-package labels show a wide range of impacts, she said, which are strongly influenced by the label design.

Madsen contrasted voluntary front-of-package labeling, which is in use in more than 30 countries, with mandatory labeling, which has been implemented in 15 countries (Global Food Research Program, 2022). She highlighted examples of voluntary label schemes that she described as aesthetically appealing, but neither eye-catching nor easy to interpret nor useful for food decision making. In the case of mandatory front-of-package labeling, she continued, packaged foods are required to carry black octagon stop sign symbols that read “high in sugar,” “high in saturated fats,” “high in sodium,” or “high in calories” if they meet the criteria for “high” in those categories. These warning-style labels require no prior education or additional context to interpret, Madsen pointed out, and she referenced one study that examined their impact to date. That study found that after the labels had been in effect, statistically significant declines had occurred per capita per day in intakes of the dietary elements called out on the mandatory labels (Taillie et al., 2021). Another impact of front-of-package labeling is reformulation, Madsen said, highlighting reductions in the sodium content of foods in the United Kingdom following the implementation of warning labels, as well as reductions in the trans fat content of foods in the United States following a requirement to disclose the amount of trans fat on product labels (Roberto et al., 2021).

Madsen cited other strategies for modifying food environments that included limiting food advertising to children, placing warning labels on advertisements for unhealthy foods, and establishing ordinances for healthy checkout lines and counters (i.e., so that these areas of retail environments stock healthy items instead of candy). She called for rethinking “what industry is held accountable for” given the compelling impact of food environments on dietary choices and intakes.

Finally, Madsen summarized her key takeaways, starting with the importance of measuring and evaluating the impact of changes in food

environments, as well as in physical activity environments, to inform obesity solutions. She reiterated that taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages are effective, but their geographic scale matters, and that front-of-package labels are also effective but must be well designed. No single approach will be sufficient, she emphasized, and a continued piecemeal approach without a broader strategy or roadmap will undermine the potential for progress in obesity prevention.

PANEL AND AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Following their presentations, the five speakers engaged in a moderated discussion and answered participants’ questions. The topics discussed included starting points for measuring policies, outcome metrics for obesity prevention policies, health outcomes of comprehensive obesity prevention policies, detecting unintended consequences of obesity prevention policies, measures of corporate behavior and community engagement, influencing corporate action, and workplace policies to promote physical activity.

Starting Points for Measuring Policy

Chriqui noted that considering the decentralized U.S. approach to policy making on obesity prevention issues, the focus will be on measuring individual policy efforts, unless a comprehensive obesity prevention strategy is developed. She suggested focusing on measures that have the greatest reach combined with the greatest impact and continuity across multiple jurisdictions. She acknowledged that policy impact can be demonstrated for a policy implemented equitably in a single jurisdiction but maintained that impact is more likely to be demonstrated when a policy is diffused across the country (if it is not enacted at the federal level). Even in the case of federal-level policies, she observed, implementation often varies at the local and state levels.

Chriqui appealed for both policies that improve nutrition and those that improve physical activity, such as policies on land use and transportation and on physical education in schools. She noted that the Community Preventive Services Task Force has identified effective policy strategies in both areas.

Outcome Metrics for Obesity Prevention Policies

Block was asked whether it is fair to require that positive impact on obesity prevalence or BMI measures be demonstrated to confirm the effectiveness of obesity prevention policies. That standard should not be required in the short term, he replied, but whether it may be more reasonable over the long term is debatable. Weight and BMI are the only available

measures of population-level effects on obesity prevention, he pointed out, noting that nationally representative surveys can provide helpful data but often are not robust or large enough to truly measure population effects.

The first outcome to measure when a policy change occurs, Block asserted, is whether the policy’s target effect was achieved. For example, does calorie labeling change people’s knowledge and recognition of the information on the label or change their food purchasing behaviors? Only after those more proximal effects can be demonstrated, Block argued, is it appropriate to consider evaluating more distal effects. Another important factor, he added, is to determine whether data are available to answer the question(s) of interest. Food retail purchasing data are often challenging to obtain, he observed, particularly for large geographic regions. Access to these data often requires partnership with a food retailer, he added, whose incentives may not be well aligned with the goals of research and policy evaluation.

Block underscored that single policies are unlikely to have a large impact on population weight, a fact he contended should influence discussions of how success is defined for obesity prevention policies. It is also important, he stressed, to develop a roadmap for how to approach progress in population-level obesity solutions.

Health Outcomes of Comprehensive Obesity Policies

Block relayed that some countries in South America have been able to measure implementation processes and impacts on dietary measures for public health policies, but not health outcomes as yet. He predicted that the same patience will be needed with obesity prevention policies as was required with tobacco cessation policies, noting that in the latter case, it took time to observe effects that progressed from process implementation to behavior change to health outcomes. He also observed that treatment is often conflated with prevention, but while both types of strategies are needed, they differ with respect to measures and effects.

Chriqui built on Block’s comments to explain that the time lag between the implementation of a policy and observation of its effects varies by policy type, context, and jurisdictional reach. To illustrate this point she contrasted a beverage tax, which takes effect relatively quickly and can easily be applied across an entire jurisdiction, with land use and transportation changes, which may take decades to implement and, in the case of complete streets projects, are executed project by project and rarely jurisdiction wide.

Detecting Unintended Consequences of Obesity Prevention Policies

Block appealed for measuring unintended consequences of obesity prevention policies, an issue that frequently dominates discussions but is not supported

by evidence. Crespo added that unintended consequences seldom are measured because policies are not evaluated. Krieger suggested that unintended consequences are often perceived and felt by individuals who are impacted by a policy. It is critical to listen to and learn from the lived experiences of these individuals, he maintained, as the policy is designed, implemented, and evaluated. Chriqui agreed, adding that implementation science approaches and mixed methods can help determine what is and is not working and what unintended consequences (positive or negative) may have resulted.

Measures of Corporate Behavior and Community Engagement

Krieger pointed to growing interest among researchers in public health policy regarding commercial determinants of health, which he described as corporate behaviors and practices that shape food environments. He contended that commercial determinants of health may be driving the obesity epidemic and therefore are worthwhile to measure. Examples of metrics to consider examining, Krieger suggested, are sales of healthy versus unhealthy products, proportions of new product introductions that are healthy versus unhealthy and share and reach of marketing and comparative marketing expenditures for healthy versus unhealthy products. Relevant measures exist even further upstream, he observed, such as a food company’s political and policy activities related to obesity, or how the company’s governance policies affect racial equity and justice both internally and in the communities where it operates. It is politically challenging, he added, to encourage companies to report that kind of information publicly.

With respect to measures of community engagement, Krieger highlighted the fundamental importance of building power within communities to enable them to shape policies that affect their well-being and reflect their values. He referenced the existence of metrics for measuring the effectiveness of coalition building, of leadership development, and of power in communities, and suggested that those metrics could offer insights for policy adoption and evaluation efforts.

Influencing Corporate Action

Krieger shared his view that the purpose of corporations is to maximize shareholder revenue and suggested that corporate interests are often at odds with health promotion, which results in market failures and externalities associated with corporate activities. Accordingly, he argued that regulations and laws are needed to protect the public interest by changing corporate behaviors, describing these measures as a powerful set of policy levers. Krieger asserted that corporations will not act on their own to contribute to healthy food environments; they must be regulated and constrained, and provided

with both incentives and disincentives, if healthy food systems are to be achieved. Madsen suggested framing such policy measures as giving corporations the support they need to remain accountable both for shareholder value and for externalities such as effects on health and the environment. Krieger appealed for a parallel effort to examine the effects of existing government policies on food environments, and shared what he called the classic example of crop insurance and agricultural subsidy policies.

Block agreed that it is unreasonable to expect corporations to change their primary goal of maximizing shareholder revenue, but pointed out that some corporations have made changes that support both that goal and the goals of public health. He suggested that such changes should be recognized as corporate best practices.

According to Crespo, consumer demand usually dictates corporate action. People want to live in healthy homes and communities, he maintained, noting that some land developers are responding to those desires.

Chriqui addressed another angle of the topic, which she described as corporations’ access to the data necessary to measure policy implementation and impact. Many of those data are difficult and expensive to access, she observed, highlighting ongoing efforts of federal and nonprofit entities to leverage resources that would give researchers access to these important data.

Workplace Policies to Promote Physical Activity

Crespo prefaced his response by suggesting that the potential impact of workplace efforts to promote physical activity should be reevaluated given the rise in remote work opportunities. Health insurance through one’s employer or through public insurance (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid) is the norm in the United States, he said, which he maintained creates pressure on employers to keep their workforce healthy. He declared that it is a corporate responsibility to promote workforce health and provide employees with opportunities for physical activity but acknowledged that multisector actions are needed to make it easier for people to be healthy in the workplace.

Chriqui highlighted a new resource from the Physical Activity Alliance and the Physical Activity Policy Research and Evaluation Network: a set of standardized measures for assessment of physical activity in workplaces, as well as policy, systems, and environmental change strategies employers can use to support physical activity during the workday. She listed the examples of offering paid time off or flex time for physical activity, promoting stretching at the beginning of one’s shift, enacting policies on physical activity breaks, encouraging walking meetings, providing incentives for taking public transit (e.g., increasing parking fees and providing transit subsidies), creating physical activity spaces, posting signage to encourage using the stairs and other active options, and providing access to bike racks.

This page intentionally left blank.