Translating Knowledge of Foundational Drivers of Obesity into Practice: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2023)

Chapter: 3 Academic and Workforce Structures That Dismantle Systemic Racism While Building an Evidence Base

The second session of the April workshop explored how to achieve academic and workforce structures that dismantle systemic racism while building an evidence base. Stephanie A. Navarro Silvera, professor of public health at Montclair State University, provided opening remarks and moderated a panel discussion with four speakers, and then facilitated a discussion and question-and-answer period with the panelists and attendees.

Silvera noted that nearly 20 years ago, the Institute of Medicine issued the landmark report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, which argued that increased diversity in the health care workforce was critical to improving the health care system (IOM, 2003). That conclusion, she recounted, was based on observations that health care professionals who were members of racialized and minoritized groups were significantly more likely than their White peers to serve minority and medically underserved communities. The report stated further that diversity in training settings could improve cross-cultural training and cultural responsiveness among all trainees, Silvera continued, and that greater racial and ethnic representation in academic programs would inform research, innovation, and quality improvement efforts. According

to Silvera, much work remains in this regard, although higher education has become more diversified in the past decade, particularly with respect to increasing diversity among undergraduate students. Growing evidence suggests that increasing diversity and equity is beneficial for all, she maintained, with such benefits as boosting innovation.

PANEL DISCUSSION: EXAMINING THE IMPACT OF STRUCTURAL RACISM ON OBESITY RESEARCH BY VIEWING THE ROLE OF ACADEMIC INSTITUTIONS AS A WORKPLACE

Silvera prefaced the speaker panel by stating that examining the impact of structural racism on obesity research requires discussing the role played by academic institutions as a workplace and how those environments can be changed to close the diversity gap. She invited four speakers to respond to two broad questions. First, how did we get here: What are the structural processes of racism that produced the current workforce, and with what effect on evidence generation, funding offerings, and research prioritization? Second, what can be done about it: What practical solutions have been successful?

A Legal Perspective

Daniel G. Aaron, Heyman fellow at Harvard Law School and attorney at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, offered five points in response to each of the above two questions. With respect to the first question, he maintained that law has played a role in workforce racism. Citing Professor Bennett Capers, he said that law school has been described as a largely White space, with the most prestigious law schools being populated by White, wealthy, privileged student bodies. He referenced the statement of Professor Asad Rahim at Berkeley Law that discussing race is often viewed as unintellectual in law school spaces, and BIPOC individuals—Black, Indigenous, and People of Color—who attend law school are often discouraged explicitly and implicitly from discussing racial issues in the law. According to Aaron, this sentiment is linked to a dust-up in the 1980s in which many law professors were denied tenure for bringing racial issues and critical race theory into the study of law. That was a consequence of pressure on universities from alumni and donors, he submitted, which showed how, at that time, money was used to control information and discourse about racism.

According to Aaron, the extraction of race and racism from legal education is manifested, for example, in Supreme Court outcomes, such as what he called the Court’s taking a hard line in considering race by framing as unconstitutional policies that remediate racial inequity. The Supreme

Court recently accepted a case that threatens to unravel race-conscious admissions in universities, he added, which he suggested would deny or reduce access of BIPOC individuals to higher education. Aaron asserted that the extraction of teaching about race and racism in education settings is occurring as well, as illustrated by efforts to ban critical race theory in schools across the United States and claims that racism is not a problem. In his view, these actions have contributed to a workforce with an insufficient education in race and racism.

Aaron’s second point in response to the first question was that nondiscrimination law is inadequate for preventing racism in the workplace and has led to attrition of BIPOC individuals from many institutions, including those in positions of power. He acknowledged that law is not the only solution to ending discrimination, but asserted that it has provided an illusion of protection.

Third, Aaron emphasized the power of corporations, which he said employ the majority of U.S. workers and also influence the foods that are produced and consumed. He acknowledged that the contributions of both corporate law and corporate power to obesity and other systemic problems are difficult to measure, and shared his view that measurement of systemic problems in the overall obesity space is insufficient. He maintained further that insufficient funding is available to study corporate power and corporate effects on structural racism.

Aaron’s fourth point was that a biology and genetics bias exists in many studies that mention race. This bias is highly problematic in discussions of racial disparities, he contended, and he suggested that opining on biology has been perceived as less political than opining on corporate power. This perception is changing somewhat, he observed, as genetic explanations of race have been criticized, and “race-based medicine” has increasingly been discredited. He added that the connection between race and genetics is steeped in a complicated history of racial oppression. Aaron briefly addressed the notion of obesity as a racist concept and the contention that physicians should adjust body mass index (BMI) cutoffs by race or ethnicity. He warned that genetic differences across races are generally viewed as a misconception, and therefore adjusting obesity cutoffs based on race is in tension with efforts to eliminate race-based medicine. While changing obesity cutoffs could equalize the frequency of obesity across racial groupings, he observed, it might obscure the vast problem of racial inequities in obesity. Aaron endorsed a focus on systemic causes of these inequities, which he said would curtail the impulse to wonder whether BMI might be a racist concept.

Fifth, Aaron conveyed his observation of a lack of intersectionality in obesity and racism studies. An expertise culture diminishes the ability to form interdisciplinary connections, he contended, and he supported

this view by pointing out that people often study discrete issues without considering the perspective of race or racism within that issue. On the other hand, Aaron suggested that dialogue on racial injustice often fails to consider public health at the forefront. What is worse, he added, is when one perspective is used to undermine another. To illustrate this point, he suggested that medical and public health articles or practice may emphasize treating obesity without considering stigma or racism’s impact on obesity, while articles on racial justice may focus on the stigma of obesity in racial and ethnic minorities while downplaying obesity as a health issue. According to Aaron, intersectional obesity and racism studies would help build a more durable and effective movement toward solving these problems.

Aaron then turned to offering five points in response to Silvera’s second question, about practical solutions. First, he suggested forming more alliances across identity groups to create more durable movements toward a nonracist workforce. He stressed the importance of allies within and outside of identity groups that experience discrimination, such as BIPOC individuals and those with overweight and obesity. He also urged alliances across disciplines, such as medicine, public health, policy, law, psychology, social work, and anthropology, as well as across class and education.

Second, Aaron stressed the need to uplift the lived experiences and voices of individuals at the ground level. Third, he advocated for promoting “demosprudence,” which he described as a legal term for practicing law in a way that is responsive to social movements. He stated that changing systems calls for integrating professional practice with such movements—which, while challenging, has been done successfully in some areas. Fourth, Aaron argued for supporting race-conscious remedies, such as programs to remediate the legacy of racism and other historical injustices. The current Supreme Court has insulated racism from being addressed, he maintained, but he suggested that collective social movements and advocacy could surmount this obstacle. Finally, Aaron reiterated his earlier point about the importance of intersectionality.

A Research Perspective

Jacqueline S. Dejean, associate dean of research at the School of Arts and Sciences and associate dean of diversity and inclusion at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Tufts University, opened her remarks by suggesting that society today is experiencing heightened racial awareness, which she called an exciting and hopeful time primed for exponential change. That heightened awareness, she contended, is accompanied by a commensurately heightened expectation of a new, authentic kind of justice that she believes is possible if awareness becomes a launching point for systems change and the unearthing of new solutions.

Dejean shared an anecdote to illustrate how change can stem from increased awareness. When working at a teaching hospital approximately two decades ago, she overheard two White dermatology research fellows discussing the disparity between White and Black test subjects in their experiences of pain caused by laser. The Black participants reported higher pain on the scale, and the two White researchers postulated that Black people exaggerate the pain experience. Dejean pointed to the subsequent published finding of a Black research fellow that varying the laser wavelength would minimize the pain experienced by subjects with darker-pigmented skin by reducing the amount of skin damage caused by the laser. Up to that point, Dejean said, laser damage for dark-skinned people had always been a foregone conclusion.

Dejean recounted her efforts, beginning in 2017, to address racial disparities in research laboratory personnel at her academic institution. Her focus was on high-performing BIPOC undergraduate students, who were not represented in laboratory settings in a ratio equivalent to their presence at the university. Dejean explained that she designed the Visiting and Early Research Scholars Experience program to provide underrepresented undergraduate prescholars with substantive research experiences that would enable them to become independent junior researchers who would design and investigate their own research questions. This program lays a foundation in both hard skills and soft skills such as self-advocacy, she continued, and also facilitates a mentor–mentee connection. Designing the program was less challenging than shifting the system to embrace access of this nature, Dejean recalled, giving the example of her difficulty obtaining racial-, ethnic-, or gender-based data from the university regarding its existing research programs. Without these data, Dejean explained, it was difficult to assess what she saw anecdotally, let alone build a case for supporting the program.

Dejean recounted her application of John Kotter’s eight steps for change, as documented in his book Leading Change (Kotter, 1996), which can be applied to work toward dismantling barriers in institutions. The book was not written to address systemic racism specifically, she commented, but its principles were applicable to the situation she faced. Her approach to applying Kotter’s eight steps was as follows:

- Step 1: Create a sense of urgency. Dejean shared her view that society is now at the point that people understand that disparity is unacceptable and appreciate the urgency of dismantling the systems contributing to disparity across institutions, industries, and the nation. Such awareness did not exist in 2017, she observed, so she started the conversation to build urgency framed around the mandate of the America Competes Act, urging her university to rise to a level similar to that of other nations that had already begun dismantling racial barriers in their institutions.

- Step 2: Build a guiding coalition. Dejean implemented this step by recruiting a small team of federally funded researchers and sharing her vision.

- Step 3: Form a strategic vision and initiatives. This happened when Dejean allowed and encouraged the team to help transform the vision, remarking that “nobody wants to be told to change something, but people will participate together to envision a change.” Implementation of this step led to the next set of steps, focused on communication to engage and enable the whole institution to share the vision.

- Step 4: Obtain buy-in. This was achieved when the small team earned buy-in and enlisted a volunteer army within the institution, Dejean explained.

- Step 5: Spread the vision and remove barriers. Dejean explained that volunteers helped spread the vision and gather more people to enable action by removing barriers. Funding was identified as a factor limiting the ability to increase the number of students involved in research labs, she recalled, but she helped identify opportunities for researchers to pursue other, supplemental funding to support their objective.

- Step 6: Generate short-term wins. Dejean said she implemented this step by celebrating her success in surpassing her goals for the numbers of faculty and students recruited to participate in the program’s first year.

- Step 7: Sustain acceleration. These small wins contributed to sustaining acceleration, which Dejean said she achieved by leveraging those wins to accelerate the change process.

- Step 8: Embed the change in the culture. Now 5 years out from starting the program, Dejean reflected on the gradual emergence of students who had never had a vision for research, or even recognized it as a career option, but have now embraced new realms of education and experience that research has facilitated.

Returning to a point she had made earlier, Dejean expressed her hope that, once achieved, the goal of increased awareness will be a launching point for systems change. In her view, the disconnect between awareness and action remains, whereby marginalized populations continue to experience the consequences of disparate systems while awareness is being acquired by others who hold the most power to enact change. Evidence-based models for change already exist, she reiterated, and she urged a willingness to shift perspective and review interpretations based on past results as a foundation for acting and implementing, which she contended could occur simultaneously with continuous learning about the problems created by inequitable systems.

An Academic Perspective

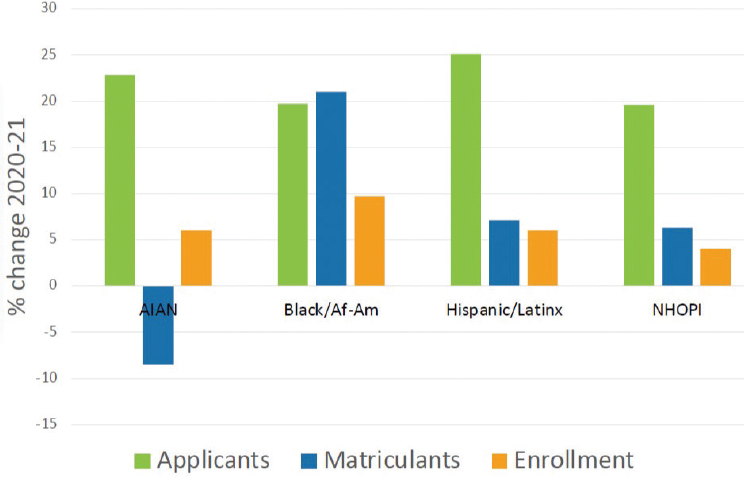

Michelle Ko, associate professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences at the University of California, Davis, discussed connections between institutional and structural racism in contemporary systems and inequities in the current workforce. She began with an example of institutional racism in medical school admissions processes, which she argued cannot be attributed solely to problems in the pipeline (i.e., K–12 grade education). She cited a study from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) (2022) reporting that a record-high number of individuals from underrepresented minority populations had applied to and enrolled in medical schools in fall 2021. She pointed out, however, that when the data are examined further, while applications to medical schools had increased among all minority populations, a proportional increase in matriculation to medical school occurred only among Black and African American applicants (Figure 3-1), and the impact on enrollment was small for all applicants. For example, a 20–25 percent increase occurred in application rates among American Indian and Alaska Native students, she observed, but matriculation decreased among this population.

NOTE: AIAN = American Indian/Alaska Native; Af-Am = African American; NHOPI = Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islanders.

SOURCE: Presented by Michelle Ko, April 19, 2022 (data from AAMC [2022]). Reprinted with permission.

Ko maintained that White supremacy is embedded in contemporary higher education policies and processes, supporting her statement with findings from interviews her and her team conducted in 2019 and 2020 with 39 leaders in medical school admissions. With respect to institutional barriers, she reported that interviewees referenced a lack of leadership commitment to advancing racial diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) despite verbal affirmation of the topic’s importance. According to one interviewee, Ko reported, other initiatives were consistently given priority when the time came to invest in changing racist systems. Another institutional barrier identified in the interviews was an overemphasis on academic metrics. Admissions leaders reported pressure to pursue higher test scores and grade point averages—beyond what they felt was appropriate for evaluating future physicians—because these metrics factor into rankings from influential entities such as U.S. News and World Report. Ko cited as a third barrier expressed during the interviews the influence of political and social connections on admission decisions. She asserted that faculty, alumni, politicians, and local community leaders maintain their preferred workforce composition in part through influence on these institutional decisions.

Ko transitioned to discussing another body of her work, now in progress, that assesses the relative empowerment of individuals in positions and offices charged with implementing DEI in U.S. medical schools and academic medical centers. Announcements of such initiatives increased in 2020 and 2021, she observed, alongside promises to address racism in health systems and health professions education. Ko elaborated on four initial themes, identified from her team’s interviews with approximately 30 people with a position related to implementing DEI within medical schools and academic medical centers:

- Wide variability exists in roles (i.e., day-to-day duties and overall expectations) and in degrees of support for achieving the role’s objectives.

- There is a mismatch between investment and expectations; for example, an individual might be expected to achieve certain outcomes but not given the staff support or budget necessary to do so.

- Interviewees were asked to promote change in areas of the institution in which they did not have direct authority, such as faculty hiring or financial spending.

- Individuals in these positions and offices charged with implementing DEI typically had limited knowledge of existing scholarship and theory on effecting organizational change.

Ko argued that DEI cannot be accomplished absent change in the foundation of schools as racialized organizations. She shared a quote from a

recent journal article on this topic: “The theory of racialized organizations argues that structural racism is often enacted through formal and informal organizational processes that privilege certain racial groups at the expense of others” (Nguemeni Tiako et al., 2021).

Ko’s final point was that structural racism in public health, health systems, and policy has promoted disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on groups historically excluded from the health and research workforce, such that the challenges to their pursuit of careers in these fields have been compounded. To support this point, she shared survey data collected in fall 2020 from a national online sample of 545 students aspiring to enter the health professions from historically marginalized populations. When asked how the COVID-19 pandemic was affecting them, nearly half of respondents reported that they at least occasionally struggled to make payments on rent and bills, and a similar proportion reported having to provide caregiving for family members (Ko et al., 2020). In addition, respondents reported challenges related to family responsibilities, food insecurity, job insecurity, and COVID-19 infection and transmission. Ko also noted an increase in reports in the literature on higher education of declines in enrollment of historically marginalized groups during the COVID-19 pandemic (Hoover, 2020; Howell et al., 2021; Liu, 2021).

In concluding her remarks, Ko emphasized the importance of changing the people in the system in tandem with changing the system itself. She appealed for institutions to examine internal policies and processes that create infrastructure for racist workforce development. As an example, she called for more changes within admissions, advising, and assessment processes as students move from undergraduate to graduate and training phases. She also suggested that institutions pursue external opportunities to dismantle institutional racism, such as collaborating with policy makers and funders to change incentives and regulations. Finally, she reminded attendees that COVID-19 response policies are workforce policies in that they impact future health and research professionals that the field hopes to recruit, support, and retain.

Perspective of a Federal Government Funding Agency

Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable, director of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), responded to the two questions raised by Silvera from the perspective of his role at NIMHD. His particular focus was on the role of external funding and its influence on who is doing the work and how race and ethnicity affect what work is valued.

Pérez-Stable began by stating that structural racism has been built on the foundation of U.S. policies implemented in the 1930s, such as

residential redlining. He showed a series of maps illustrating how historical redlining policies influenced social segregation and the trajectory of health outcomes in the District of Columbia, with areas marked on the Federal Housing Administration’s maps as low-grade, Negro developments being populated predominantly by Black people today. He reported that people in those same areas have a 10-year lower average life expectancy, experience a higher concentration of food deserts, and have higher rates of heart disease among adults compared with areas populated predominantly by White people. According to Pérez-Stable, such patterns are seen throughout many other cities in the Eastern and Midwestern parts of the country, and although redlining is now illegal, the effects of racial and socioeconomic segregation are manifest today. As an example, he pointed to the interplay of environmental factors and social determinants of health and their effects on the development of chronic diseases (e.g., immune system activation, oxidative stress, and potential microbiome effects).

Pérez-Stable characterized diversity in science and medicine as a “demographic mandate” given the importance of developing a diverse clinical workforce to care for the U.S. population, 37 percent of which consists of racial and ethnic minorities. He also called for developing a diverse biomedical scientific workforce to conduct better biomedical research. Additionally, he called for efforts to engage underrepresented populations to participate in clinical research, suggesting that such efforts would best be undertaken by underrepresented scientists, who are connected to these communities. Pérez-Stable referenced the 2020 U.S. Census, which showed that more than half of U.S. children are from a racial or ethnic minority. He warned that the health and medical profession will therefore be alienated from a large portion of the population if it does not diversify and stressed the importance of ensuring fair representation in this profession and leveraging the intellectual capital of these underrepresented groups.

Pérez-Stable briefly discussed the concept of critical diversity, which comes from the field of sociology. Critical diversity emphasizes not only the equal inclusion of people from all backgrounds and parity at all levels, he explained, but also gives special attention to those who are viewed differently because of exclusionary practices of the majority group in power (Herring and Henderson, 2012).

Moving on to the current status of diversity in the medical workforce, Pérez-Stable referenced the study from AAMC (2022) cited earlier by Ko. He reported that this study highlighted the proportion of African American, Latino/Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native medical school graduates in 2020 (7 percent, 6 percent, and <1 percent, respectively) (AAMC, 2022). The proportions are similar, he noted, for new PhDs in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (NSF, 2020). After adjusting for sex, clinical specialty choice, and educational loan burden, the

study found that medical school graduates from underrepresented groups are more likely than their White counterparts to work in underserved areas. Pérez-Stable concluded his statistical review by citing evidence indicating that diverse teams are more innovative and conduct more rigorous research relative to teams with less diverse members (Garcia et al., 2018).

Pérez-Stable next turned to the “cultural taxation” that he said affects underrepresented minority individuals on university faculty (Pololi et al., 2013). They are often asked to serve on multiple committees to “represent” these groups and satisfy university requirements for diversity and inclusion, he pointed out, and may be asked to take responsibility for all diversity efforts. Relative to their White peers, they receive excess mentor-ship requests from students, residents, and other faculty, which he said are well-intentioned but, in combination with the other requests for their time, often have negative consequences. In addition, Pérez-Stable said, they experience isolation and lack of community; discrimination; discomfort with the culture; and negative perceptions of relationships because of their difficulty relating to certain aspects of a predominantly White, male-dominated culture. Particularly in medical schools, he observed, junior faculty from underrepresented minorities receive limited credit for any service in the community or professional settings, and compared with their White counterparts, give lower survey scores on equity and institutional efforts to improve diversity (Pololi et al., 2013).

Pérez-Stable suggested a series of actions that institutions can take to address diversity. First, leadership can demonstrate commitment to change. Pérez-Stable referenced strong statements against racism made by leaders in institutions across the country following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, which he called a “sea change,” but he argued that it is still unclear whether those statements will yield long-term, sustainable commitments. Another action, he continued, is to promote and measure organizational change using metrics to evaluate organizational climate, lest organizations simply give the issue lip service. According to Pérez-Stable, training in unconscious bias is likely beneficial for raising awareness and for this reason is worthwhile, although evidence demonstrating its impact on behavior change is limited. A third action is to track and promote diversity by holistically reviewing admissions and hiring. Tracking applicants’ racial and ethnic identities, socioeconomic backgrounds, and national origins is a way to measure baselines as part of such a review, he suggested, and he encouraged greater openness to interviewing medical school applicants who may not have the highest Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) scores or the most prominent undergraduate universities as their alma mater. Lastly, Pérez-Stable highlighted the value of connecting early-career faculty with mentors who have networks through which to create pathways of knowledge, awareness, and further connections. He pointed out that these networks do not exist for many faculty members from underrepresented

groups and maintained that scientists who are more established in their careers have a responsibility to help integrate more-junior scientists into these pathways.

Pérez-Stable ended by describing NIH’s Faculty Institutional Recruitment for Sustainable Transformation program, an initiative with the goal of creating cultures of inclusive excellence to establish and maintain scientific environments that can cultivate and benefit from a full range of talent. The program pursues this goal by funding faculty–cohort models for hiring, multilevel mentoring, and professional development. Awardee institutions receive grant funding to hire cohorts of 6 to 10 faculty per year for a set number of years, Pérez-Stable explained, and these faculty must be committed to promoting diversity and sustaining a culture of inclusive excellence in the institution. The program established a coordination and evaluation center, he added, to assist cohort awardees in conducting a comprehensive evaluation of the program by developing and harmonizing measures of institutional culture change, which is expected to result from hiring more faculty committed to such outcomes and to spreading that commitment among their peers. The first year of funding was approved in September 2021, he recounted, and six institutions were selected to hire the program’s first cohort awardees, along with an additional institution to serve as the initiative’s first coordination and evaluation center.

To conclude his remarks, Pérez-Stable reiterated his belief that diversity in the scientific workforce is an inherent advantage in advancing its missions. He maintained that the United States is at a critical point, stating that, while much discussion about this issue has occurred, the needle has scarcely moved. He stressed the need for evidence to show the benefits of better access to quality health care for minority patients. He also called for evidence to clarify and elaborate on the anticipated benefits of diversifying academic and research institutions. Lastly, he called for acknowledging the U.S. history of structural racism and discrimination.

PANEL AND AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Following their presentations, the four panelists engaged in a moderated discussion and answered participants’ questions. They addressed moving from discussion to action on race and racism, avoiding “cultural taxation” of underrepresented investigators, and leveraging “low-hanging” legal strategies for advancing obesity solutions.

Moving from Discussion to Action on Race and Racism

Pérez-Stable recalled that his institute, NIMHD, has had conversations about racism as a research construct in science. These discussions have not always been polite, he admitted, but submitted that it “breaks the cycle”

when leadership raises the importance of discussing this topic. Such conversations should include all staff, he submitted, from senior leadership to early-career employees and student workers. Silvera emphasized that the shift from discussion to action on these topics is challenging. Dejean suggested that a first step is to create spaces where people can observe and participate in such conversations at their own comfort level, and described how her institution, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Tufts University, has implemented monthly community dialogues where speakers discuss predetermined topics about diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice and reserve ample time for audience questions. These dialogues provide a safe space for such discussions, she said, and help people practice speaking about and initiating conversations on these topics, which she said is a key step in changing the climate and culture.

Ko echoed Aaron’s suggestion about identifying allies and added that this is an important way to secure support when initiating conversation about dismantling structural racism. She also echoed an earlier point about identifying common ground, such as a desire to meet students’ basic needs or address the mental health impacts of racial injustice, to frame conversations about inequity. She suggested that leaders in academia could spur discussion and action to address institutional racism by deciding that their institution will not participate in the U.S. News and World Report college rankings. Silvera recognized that prospective college students and their parents want something like those rankings to help guide their decisions, but they do not have full visibility into the factors that influence the metrics used to produce the rankings.

Avoiding “Cultural Taxation” of Underrepresented Investigators

In response to a question about how to ask underrepresented investigators to lead diversity efforts without overtaxing them, Pérez-Stable contended that the simple answer is to increase the number of minoritized individuals in academic and research institutions. He appealed for giving early-career faculty the space to focus on establishing their academic credentials instead of asking them to lead diversity efforts in their institutions. As investigators become more established and tenured in their fields, he suggested, they can dedicate time to diversity efforts without compromising or giving up other activities.

Ko agreed that junior faculty should be protected and called for institutional leadership to value and reward diversity efforts. She urged reevaluating the bases on which an institution’s value is determined and suggested that it is inappropriate for value to be based on the amount of its NIH and other federal funding.

“Low-Hanging” Legal Strategies for Advancing Obesity Solutions

Aaron recalled the difficulty faced by some communities in enacting policy changes to improve access to healthy food, such as state and federal laws that prohibit the exercise of local power. High-level blocking of community power is discouraging, he said, and he suggested that building community and promoting political activism could help overcome the legal system’s opposition to social change. In terms of policies, he favored taxes on sugary or processed foods and subsidies to improve the availability of healthy and nutritious foods.

This page intentionally left blank.