Translating Knowledge of Foundational Drivers of Obesity into Practice: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2023)

Chapter: 8 Moving toward Solutions: Understanding Community Dynamics in Relation to Power and Engagement

The third session of the July workshop continued the focus on community power dynamics as a key component of systems that drive obesity. Sara J. Czaja, professor of gerontology and director of the Center on Aging and Behavioral Research in the Division of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, moderated the session’s two speaker presentations, which were followed by a panel and audience discussion.

USING A COMMUNITY-ENGAGED APPROACH TO DEVELOP A HEALTHY LIFESTYLE INTERVENTION FOR ADOLESCENTS WITH OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY

Michelle Cardel, senior director of global clinical research and nutrition at WeightWatchers, discussed her experience using a community-engaged approach to develop a healthy lifestyle intervention for adolescents with overweight and obesity.

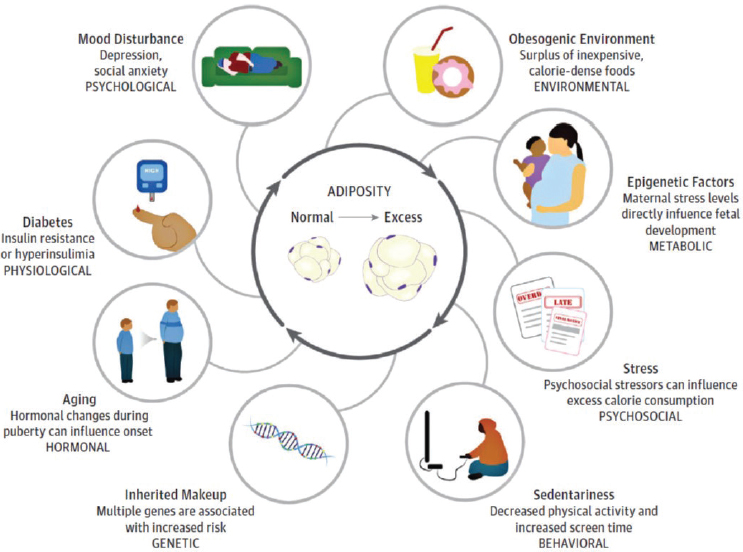

Cardel began by emphasizing the complexity of the disease of obesity, describing it as a multifactorial disease often resulting from a variety of factors, including environment, behavior, and/or physiology. She shared a figure to illustrate how obesity can develop from genetic, hormonal, physiological, metabolic, behavioral, psychological, environmental, and sociocultural factors (Figure 8-1).

SOURCE: Presented by Michelle Cardel, July 25, 2022. Cardel et al. (2020b). Reprinted with permission from the American Medical Association.

For context, Cardel noted that the prevalence of obesity in children aged 5–19 increased from less than 1 percent in 1975 to close to 19 percent in 2016 (WHO, 2021), and that treatment options for pediatric obesity depend on a child’s age and degree of excess weight. She then described how behavioral treatment programs serve as the foundation across treatment modalities, even when additional treatments, such as pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery, are considered (Brei and Mudd, 2014; Ells et al., 2018; Golan and Crow, 2004; Sherafat-Kazemzadeh et al., 2013). The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force currently recommends screening for obesity in youth aged 6 and older, she continued, and if obesity is present, the child is referred to a comprehensive, intensive behavioral treatment program. These programs include nutrition, physical activity, and behavior modification components delivered during at least 26 contact hours over a period of 2–12 months, but Cardel pointed out that programs with more than 52 contact hours within 12 months have demonstrated the highest likelihood of effectiveness. It is encouraging, she added, that interventions appear to be equally effective for Hispanic, Black, and non-Hispanic White populations (USPSTF, 2017).

Cardel elaborated on approaches to obesity management in youth that center on family-based behavioral treatment programs (Hayes et al., 2016). These approaches typically use structured rewards and goals, with parents being asked to model healthy eating behaviors and modify their parenting techniques during mealtimes to incorporate praise and positive reinforcement. The lifestyle modification component of pediatric behavioral weight management interventions includes dietary modifications, which Cardel explained often use the traffic light diet concept (Cardel et al., 2020b; Díaz et al., 2010; Epstein and Squires, 1988; Ho et al., 2012, 2013; O’Malley et al., 2017; Oude Luttikhuis et al., 2009; Steinbeck et al., 2018), in which green foods are those high in nutrients and low in energy, yellow foods are those high in both nutrients and in energy, and red foods are those low in nutrients and high in energy. She added that programs facilitate enjoyable opportunities for at least 60 minutes of daily moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and limit screen time to no more than 2 hours per day. An overall emphasis is on behavior change, she summarized, not just for the patient but for the whole family.

Best practices in family-based treatment tend to focus on children younger than 12, Cardel reported, whereas data are lacking for adolescents. The available data suggest that current interventions are only modestly effective for adolescents, she observed, because this age group is more autonomous than younger children, may or may not benefit from parental involvement (data are mixed), and is developing self-regulation skills. This research gap for adolescents led Cardel and her team to explore how to develop interventions tailored to adolescents’ needs and preferences.

Cardel recounted that in carrying out this research, her team discovered emerging data from Drexel University on a weight loss intervention that

enhances standard behavioral therapy with a new component called acceptance-based therapy (ABT) (Forman et al., 2016). ABT is characterized by the acceptance of uncomfortable states and emotions, mindfulness, values-based living, and self-regulation skills. Cardel cited evidence in adults indicating that an ABT approach can result in a greater than 13 percent body weight loss over a 1-year period, with no differences by race, sex, or education, a perspective she said parallels what is observed with pharmacotherapy and is higher than that achieved with standard behavioral therapy (5–8 percent body weight loss over a 1-year period). According to Cardel, this finding was exciting because it gave her team the idea of developing a proposal to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for funding a modified version of this intervention that would be appropriate for adolescents.

The goal of this effort, Cardel explained, was to develop, tailor, and implement an ABT therapy weight loss intervention for adolescents. Her team aimed to make the intervention salient for weight loss among adolescents and to improve their self-regulation skills, particularly for those from vulnerable communities. The first year of the grant was spent doing formative work, Cardel relayed, to understand the lived experiences of adolescents with overweight and obesity.

Cardel described focus groups that identified adolescents’ perceived barriers to and facilitators for weight loss and made clear that boys and girls experienced weight status differently (Cardel et al., 2020a). Girls reported that they were highly aware of their excess weight, that adults and friends in their lives had talked to them about it, and that they were trying to make changes to improve their weight status. Boys shared that their weight status had not been discussed with them and in some cases, they were trying to gain weight to improve their sports performance; only the boys with severe obesity conveyed that they wanted to address their weight status. According to Cardel, those overall findings demonstrated that adolescent boys and girls have strikingly different perceptions about both weight status and barriers to and facilitators of weight loss and healthy lifestyles. The focus group results confirmed the need for sex- or gender-stratified interventions, she said, and suggested that tailoring weight management interventions accordingly could improve their feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness.

Cardel then discussed the second component of the focus groups, which explored the preferences of adolescents with overweight or obesity for behavioral weight loss interventions (Lee et al., 2021). Focus group participants were extremely insightful, she recalled, reporting that they wanted a program focused on an overall healthy lifestyle targeting physical, mental, social, and emotional health, instead of weight loss alone. This finding was aligned with new guidelines from the Canadian Medical Association, Cardel remarked, which also included an emphasis on moving away from weight-centric approaches to a more holistic focus on health.

Another discussion topic in the focus groups was preferences for other individuals whom adolescents wanted to be involved in the intervention. Participants also requested a relatable instructor with weight loss experience. They felt differently about parental involvement depending on whether it was perceived as a support for or hindrance to success, Cardel continued, thereby indicating the importance of providing flexibility to allow participants to decide what is best for their journey. Another finding emerging from the focus groups was that adolescents saw weight as a vulnerable topic, and they did not want to discuss it in front of people who identified with a different gender or who were a different sex from them.

Finally, Cardel reported that focus group participants identified incentives, engaging activities, and electronic communication as core components for program engagement and retention. As incentives they cited such things as water bottles, laptop stickers, t-shirts, or other giveaways—not financial compensation—and they also wanted the program to be fun and enjoyable. Females emphasized socializing and relationship building.

Cardel next described the approach to program development, which she said focused only on adolescent girls (aged 14–19), given the finding that sex-stratified interventions were needed (Lee et al., 2022). After a curriculum rooted in the ABT approach was drafted, the research team hired adolescent citizen scientists with the lived experience of overweight and obesity to collaborate with the researchers as equal partners in every aspect of the intervention development. These adolescents also helped name the program WATCH (Wellness Achieved Through Changing Habits) and developed its logo and recruitment materials. The team began with a feasibility pilot involving two cohorts (N = 13) that included greater than 60 percent racial/ethnic minority participants. The pilot, Cardel explained, consisted of a healthy lifestyle program with 15 group sessions conducted over a 6-month period (Cardel et al., 2021). Program attendance and engagement were rewarded with points that could be redeemed for prizes that had been suggested in the focus groups.

Cardel reported results from the feasibility pilot, indicating that 84.6 percent of participants completed the 6-month intervention and assessments, and 90.9 percent completed all 15 sessions (Cardel et al., 2021). She pointed out that these results are highly impressive for an adolescent intervention, and she shared other promising results, such as positive changes in a variety of metrics including overall quality of life and depression. Participants reported high satisfaction with the program, Cardel added, based on qualitative feedback collected at the end of each session and findings from semistructured interviews conducted at the end of the intervention.

A pilot randomized controlled trial began in August 2020, Cardel continued, adding that it was virtual because of the COVID-19 pandemic. A paper on this pilot has since been published, she noted, and plans were made to assess the program’s effectiveness in a fully powered trial in fall

2022 (Newsome et al., 2022). The bottom line, she said in summary, is that given impressive weight loss results observed in adults treated with ABT, along with pilot data demonstrating the approach’s feasibility and acceptability in adolescents, ABT could represent a highly effective obesity intervention for this population, although more research is needed.

Recognizing the current focus on personalized medicine, Cardel suggested that, moving forward, it will be important to consider the role of psychosocial components in the development of obesity and the idea that zip code may be as important as genetic code in the development of overweight and obesity. She urged the field to integrate implementation science and community-engaged approaches in accordance with the concept of “nothing about us, without us,” and to develop interventions that are acceptable to and effective in underserved groups (Kaiser et al., 2020).

THE CONNECTICUT HISPANIC HEALTH COUNCIL SNAP-ED PROGRAM

Rafael Pérez-Escamilla, professor of public health in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the Yale University School of Public Health, presented a case study to illustrate how community engagement led to the successful development, implementation, and sustainability of the Connecticut Hispanic Health Council SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program)-Ed program. The program has been in place for nearly 30 years, he said, founded in 1995 through a partnership between the University of Connecticut College of Agriculture and Natural Resources and the Hispanic Health Council, and funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s SNAP-Ed program. The program’s mission, he explained, is to improve food and nutrition security and nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among Hispanics in Connecticut through a community-engaged life-course approach.

Pérez-Escamilla defined “community-engaged” to mean that the program’s structure, strategy, and end-to-end operations are informed by relationships of trust and respect with the community. A culturally tailored approach, he elaborated, integrates dignidad (dignity), respeto (respect), confianza (trust), familiarismo (familiarism), and personalismo (personalism), and is the basis for empowerment and social support, which he said are core to effective service models. Since day one, he recounted, the program aimed to implement evidence-based practice models; multidisciplinary, culturally tailored approaches; thorough evaluation of process (or implementation), client satisfaction, and impact outcomes; and strong partnerships built from a social justice perspective.

The program’s structure and evaluation strategies followed rigorous program design methods, Pérez-Escamilla said, informed by a process

grounded in community-based participatory research focused on understanding the community’s needs and wants. The process was highly iterative and developed alternatives responsive to different scenarios, he continued, then the stakeholders together chose approaches based on evidence and local context. Pérez-Escamilla reminded attendees that as programs are implemented and begin to mature, it is important to continue conducting process and impact evaluation. The program development and evaluation approaches were developed through an equity and antiracism lens, he added, although these specific terms were not used in the mid-1990s. He credited the program’s framework with allowing it to grow and to be innovative and successful.

Pérez-Escamilla presented findings from an initial wave of needs assessments conducted during the formative evaluation phase of the program in the mid-1990s in Hartford, Connecticut, with Hispanic families with infants and toddlers. These findings revealed a high rate of overweight (about 20 percent) among young children, he reported, as well as low access to health care, suboptimal infant feeding practices (e.g., low breastfeeding rates and high consumption of sugary beverages and other unhealthy products), very low fruit and vegetable intake, scarce nutrition education in schools, sparse nutrition knowledge among caregivers and teachers, and social injustice reflected in very high rates of poverty and household food insecurity.

According to a childhood obesity prevention life-course framework, Pérez-Escamilla continued, it is not enough to wait until children are of school age to start addressing excess weight because fundamental drivers of childhood obesity are established prior to gestation (Pérez-Escamilla and Bermúdez, 2012). In support of this statement, Pérez-Escamilla pointed out that prepregnancy body mass index and excess gestational weight gain predispose an infant to childhood obesity, a risk that is exacerbated by suboptimal infant feeding practices that lead to excessive weight gain during infancy and subsequently to an elevated risk for childhood obesity. Accordingly, he recounted, the program conducted a series of innovative social marketing campaigns accompanied by culturally appropriate ancillary materials addressing preconceptional nutrition issues among young adults, nutrition during pregnancy, and breastfeeding. A campaign evaluation indicated that more frequent exposure to the marketing materials and greater diversity in the types of media viewed were associated with higher intake of fruits and vegetables (Motkar, 2003).

Pérez-Escamilla then elaborated on the Breastfeeding Peer Counseling program launched more than three decades ago, which from its inception has involved Puerto Rican mothers in the community, peer counselors, and leaders in the community and health care systems (Rhodes et al., 2021). This program, he stated, is supported by evidence, including that from

randomized controlled trials, and has been deemed a best practices program by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Institute of Medicine, and UNICEF together with the World Health Organization (IOM, 2012; Shealy et al., 2005; UNICEF and WHO, 2021).

Community-engaged implementation research is a powerful approach to advancing evidence-based childhood obesity prevention efforts, Pérez-Escamilla asserted, noting that the program has been scaled up in Connecticut, where it reaches around 10,000 children each year. He mentioned the program’s culturally sensitive, evidence-based infant feeding guides; a puppet show series that teaches young children from preschool through 4th grade about healthy eating, food safety, physical activity, and where foods come from; and a “from the farm to the table” coloring book that is distributed in schools. The program’s community engagement enabled it to continue services during the COVID-19 pandemic, Pérez-Escamilla added, noting that in-person engaging community events, including health fairs, have resumed.

Pérez-Escamilla credited the success of the SNAP-Ed program to a major NIH grant for establishment of the Connecticut Center for Eliminating Health Disparities among Latinos (CEHDL). The grant partners—the University of Connecticut and the Hispanic Health Council—received $8.25 million, half of which was directed to the Hispanic Health Council. Pérez-Escamilla reported that the CEHDL conducted research on diabetes self-management programs led by community health workers; strengthened the Breastfeeding Heritage and Pride program; and established the Hartford Mobile Produce Market, which has inspired a number of food prescription programs in the city. New partnerships will allow the Hispanic Health Council’s SNAP-Ed program to implement produce prescription programs, he added, including one for Hispanic women during pregnancy and lactation supported by new federal funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) GusNIP (Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program) initiative via the Wholesome Wave organization.1

In conclusion, Pérez-Escamilla stressed that to be effective, community-engaged nutrition programs need to be equitable and person- and family-centered. To this end, he maintained, community stakeholders need to be engaged in every stage of the process, from program conception to evaluation and sustainment, and community structures, needs, and wants need to be considered in all decisions. He asserted further that effective community-engaged programs need to adhere to social justice principles, including health equity and food security, and to be informed by antiracism systems frameworks.

___________________

1 For more information on the USDA award through the Wholesome Wave Organization, visit https://www.wholesomewave.org/news/usda-grant-awarded (accessed January 25, 2023).

Finally, he stressed that community-engaged programs must be systematically planned, implemented, and evaluated. In closing, Pérez-Escamilla called for using mixed-methods implementation science approaches to design effective nutrition programs that take community systems into account.

PANEL AND AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Following the two presentations summarized above, Czaja facilitated a discussion and question-and-answer period with the speakers. She began by asking them to summarize key takeaways from their presentations, and then posed questions on topics including barriers to the use of ABT, recruiting adolescent citizen scientists, facilitators of the Hispanic Health Council’s success, nontraditional funding models for community-engaged programs, and promising population-level obesity solutions.

Key Takeaways from the Presentations

Cardel emphasized that obesity is a complex, multifactorial disease that calls for a variety of treatment approaches. She cited implementation science as one strategy for optimizing behavioral treatment approaches through a community-engaged approach, and urged researchers to develop interventions in partnership with individuals from the populations they are intended to benefit.

Pérez-Escamilla highlighted the importance of considering a life-course approach to health promotion. To illustrate this point, he reiterated that obesity prevention needs to begin before babies are conceived because biological factors can interact with racism and other socioecological factors in a way that enhances obesity risk from conception and throughout the lifespan. He also espoused the value of an assets-based approach that sees communities through the lens of the knowledge and resources they can contribute to empowering solutions instead of viewing them as sick, vulnerable entities that need outside parties to save them.

Barriers to the Use of Acceptance-Based Therapy Approaches

Cardel shared her perspective that the greatest barrier to implementing an ABT approach is that these are relatively intensive interventions that are challenging to scale. Most of the data supporting this approach were collected from interventions delivered by PhD-level psychologists or interventionists, she elaborated, rather than other professionals such as community health workers. She contended that more research is needed to identify delivery mechanisms that are more sustainable and easily disseminated while retaining the same level of efficacy.

Recruiting Adolescent Citizen Scientists

Collaborating with adolescent citizen scientists was an “absolute delight,” Cardel said, explaining that these partners were recruited from the group of adolescents who participated in the focus groups conducted as part of the intervention’s formative research. The goal, she said, was to ensure a diverse set of voices and experiences on the research team, which guided her team’s outreach to focus group participants who had presented a diversity of viewpoints from the perspective of age, race, ethnicity, severity of obesity, or life experiences.

Facilitators of the Hispanic Health Council’s Success

Pérez-Escamilla shared that the Hispanic Health Council was established after a Puerto Rican baby died in her mother’s arms on a bench in front of a Connecticut hospital because no one spoke Spanish in the emergency room, so they did not know what was happening. That incident launched a wave of activism, he recalled, which led to funding for community-based organizations like the Hispanic Health Council. A robust community nutrition research department was also established at the agency, he added, and soon thereafter, USDA agreed to establish a SNAP-Ed program there in partnership with the University of Connecticut. At that time, Pérez-Escamilla said, the concept of conducting community-engaged formative research to inform interventions was relatively new, but the combination of the Hispanic Health Council’s strong research culture, its community-engaged connections, and its strong partnerships with the health care system were key elements that led to the initiative’s success.

Nontraditional Funding Models for Community-Engaged Programs

Pérez-Escamilla recounted the Hispanic Health Council SNAP-Ed program’s unusual history of being a direct recipient of USDA funding. He explained that USDA did not typically give money directly to a community-based organization, but that eventually the SNAP-Ed funding for this program was granted directly to the Hispanic Health Council instead of the University of Connecticut. The organization was entitled to receive and be the primary manager of the resources, he submitted, because it was responsible for carrying out the day-to-day work on the front lines. Pérez-Escamilla held up this example of breaking bureaucratic barriers across funding agencies and institutions as the kind of system change he believes is needed, and he predicted that more payers will soon reimburse community-based organizations directly for evidence-based health services provided by community health workers.

Promising Population-Level Obesity Solutions

According to Cardel, a promising opportunity to deliver population-level impact is the development and dissemination of effective behavioral weight management strategies that are delivered in a digital format. This format has high potential for scalability, she explained, because more than 90 percent of adults have Internet access through a smartphone, and the barriers to reaching people digitally continue to diminish as Internet access expands. In Cardel’s view, intensive behavioral weight management centers will continue to play a key role but are insufficient to meet the demand for the country’s 14 million adolescents with overweight and obesity, given that fewer than 50 centers with a focus on pediatric obesity treatment exist.

Pérez-Escamilla stressed the importance of using systems-level frameworks to support the implementation of evidence-based programs across multiple levels of the socioecological model throughout the life course. The complex, multifactorial nature of obesity makes it impossible for a single program to significantly reduce the prevalence of population-wide obesity, he asserted, clarifying that each initiative has a role to play in collective efforts that can positively impact obesity prevention and treatment.

This page intentionally left blank.