Translating Knowledge of Foundational Drivers of Obesity into Practice: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2023)

Chapter: 4 The Effect of Communications on Perceptions and Understanding of Obesity

The third session of the April workshop featured two presentations about communication’s effects on perceptions and understanding of obesity, which were followed by a facilitated discussion and question-and-answer period with attendees. Bruce Y. Lee, professor of health policy and management at the City University of New York Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy and executive director of the university’s PHICOR (Public Health Informatics, Computational and Operations Research) initiative and Center for Advanced Technology and Communication in Health, moderated the session.

COMMUNICATION SYSTEMS

Laura Lindenfeld, executive director of the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science and dean in the School of Communication and Journalism at Stony Brook University, discussed communication as a system and its role in obesity solutions.

Lindenfeld began by sharing her view that communication plays a critical role in addressing complex problems such as obesity. Complex or “wicked” problems, she reminded attendees, are difficult to predict; have multiple, unintended, or unforeseen outcomes; have interdependencies that can make solutions appear intractable; have conflicting viewpoints about the relative causes and solutions; and require systems-based solutions. Lindenfeld elaborated on her beliefs that (1) it is critical to adopt a systems-based understanding of and approach to communication about complex problems such as obesity, and (2) communication must be based in empathy that is driven by engagement with individuals and institutions within the system.

According to Lindenfeld, communication is both an act of conveying meaning and a system that shapes the interrelationships of different communities; institutions; and stakeholders, such as scientists and health care professionals. This system can be viewed as one that interacts with the system of drivers that contribute to obesity challenges, she suggested, adding that part of the communication infrastructure that is critical to problem solving at the systems level is the ability to craft powerful forms of collaboration through empathy and engagement. Empathy calls for engaging directly with individuals and institutions that are entrenched in the systems involved in the problem, she explained, in order to understand and appreciate the vantage point from which others experience and approach communication instead of assuming that one’s own lived experience is universal.

Lindenfeld turned to discussing three areas in which communication interventions can strengthen linkages between knowledge generation and action, which she said could spur meaningful change in addressing obesity. The first is science communication, including how scientists are trained to

communicate. Lindenfeld observed that the field of science communication has received increasing attention, as exemplified by the National Academies’ Sackler Colloquium of 2012, which highlighted the importance and growth of the field.1 She shared an excerpt from the introduction to the colloquium’s papers (Fischhoff and Scheufele, 2013):

The success of scientists’ communication depends on their awareness of the role that their work plays in public discourse. Although scientists may know more than anyone about the facts and uncertainties, applications of that science can raise complex ethical, legal, and social questions regarding which reasonable people may disagree. As a result, if scientists want to be effective in their communication, they must understand and address the perspectives of interest groups, policymakers, businesses, and other players and debates over decisions that require scientific expertise.

According to Lindenfeld, training programs can help scientists and health care professionals develop the critical ability to communicate science accurately and effectively so as to support decision making. She described her own organization’s (the Alda Center’s) training program, which works with approximately 20,000 scientists and health care professionals nationally and internationally. The program’s approach is unique, she explained, in that it uses improvisational theater (“improv”) to invite trainees to embrace the challenges of working across cultures and contexts with a creative lens and to practice genuine, responsive listening through empathy.

Lindenfeld shared two rules of improv. The first is to embrace the concept of “yes and”—to accept the reality of the situation at hand, say “yes,” and suggest how one might add to rather than shut down the conversation. The other is to make one’s partner look good. Extending empathy is a key part of the second rule, Lindenfeld elaborated, clarifying that it is not synonymous with sympathy. Empathy can be thought of as appreciation of another individual’s or group’s experiences, which she said does not necessarily require agreement but does require according dignity and respect to others.

Lindenfeld called for the inclusion of science communication—how to communicate with other scientists as well as with nonscientists—in researcher training. Integrating empathy into such training is powerful, she maintained, because it reminds trainees of what she termed “the curse of knowledge.” What it means to be cursed by one’s own knowledge, she explained, is to fail to see that others do not necessarily think and

___________________

1 For more information about the 2012 National Academy of Sciences Colloquium on “The Science of Science Communication,” visit http://www.nasonline.org/programs/nas-colloquia/completed_colloquia/science-communication.html (accessed January 27, 2023).

communicate in the same terms. Empathy helps bring one out of that mindset, she asserted, and promotes imagining how others might think and feel.

Lindenfeld moved on to the second major area with potential to effect tangible change in obesity: interdisciplinary collaboration. She contended that, although challenges such as obesity call for strong collaboration across disciplines, interventions and training programs rarely focus on targeting changes in communication to better prepare teams to work together. She referenced a growing body of literature on team science that offers powerful insights into strategies for creating more productive team collaboration. According to Lindenfeld, the deep level of collaboration—across people and institutions from wide-ranging, diverse contexts—needed to address such challenges as obesity requires that the field integrate best practices from team science into the design and management of teams.

The third area with potential to yield meaningful change for obesity, Lindenfeld continued, is partnerships and engagement. In her view, humility and empathy are critical foundations of the partnerships, collaboration, and engagement required for obesity solutions. Operating from a genuine sense of care for the well-being of others is critical to moving the needle, she elaborated, adding that those relationships are part of the communication system that must be nurtured.

Lindenfeld recounted a concept in the literature—coproduction of knowledge—that involves collaboratively designing and conducting research to promote more useful and meaningful research outcomes for the intended recipients. This concept, she said, highlights the importance of incorporating collaboration with community members into the research process so that researchers understand their perspectives, values, attitudes, and needs and build trusting partnerships before the research begins. Such knowledge helps researchers understand the community’s preferences and expectations in advance, she continued, which she suggested can prevent misalignment of what researchers view as a community’s needs and what community members view as their needs.

Lindenfeld encouraged attendees to consider building more interdisciplinary project teams that include communication researchers who can help establish relationships and mutual trust between each field’s researchers and communities and make coproducing knowledge a reality. One strategy, she elaborated, is to design research projects iteratively so that communities can provide input at different stages, and another is to prioritize researcher training in ethics, conflict resolution, and genuine listening. Lindenfeld contended that empathy rooted in humility yields understanding and also sparks curiosity and respect, which she said is critical to the type of transformative collaboration and engagement needed to confront obesity and other such challenges.

Lindenfeld ended by suggesting questions that might emanate from curiosity sparked by empathy: How might we consider what information people need and how they need to receive it? How might we create solutions through genuine partnerships? How might we put people first when conducting research and designing solutions? How might we integrate communication more directly into the science we fund that we hope will serve societal needs? What does it look like to assume that we can design research to align with societal needs?

STORIES DESIGNED TO CAMOUFLAGE OBESITY-RELATED HEALTH ISSUES: A CASE STUDY OF SODA MARKETING TO LATINOS

Neal Baer, a showrunner, television writer/producer, physician, author, and lecturer at Harvard Medical School and the Yale School of Public Health, discussed the power of storytelling to change the way people think about problems and solutions, and applied this information to people’s perceptions of contributors to obesity. He focused on advertisements, which he said are a form of storytelling that deserves attention based on its ubiquity in society and its ability to affect people’s decisions about what to eat and drink.

Baer shared his view that obesity is a problem with multifactorial causes influenced by social determinants of health. He used the example of soda—which he described as a nutritionally poor, cheap-to-produce product that became a driver of “mammoth profit” through ingenious advertising, lobbying, and marketing—to illustrate this view. Soda, he stated, can be viewed through multiple lenses to understand its contribution to obesity. He described it as the hub of a wheel, with spokes connected to such outcomes as chronic disease–related health effects, environmental impacts, jobs, advertising, philanthropy, taxes, government subsidies, and legal issues. The wheel image conveys that a product’s effect on health and obesity is only one aspect of the system, he explained, stressing that one must explore the other effects to understand the product’s full impact and why addressing only its health impacts may not gain much traction.

Baer elaborated on the spokes, starting with health. Despite the recommendation of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans that intake of sugar-sweetened beverages be limited to small amounts and most often replaced with beverage options that contain no added sugars, such as water, sugar-sweetened beverages are the top contributor to added sugars in U.S. diets, and people in the United States consume an average of more than 200 calories per day from these beverages (USDA and HHS, 2020). The health effects of soda have been well-studied, Baer added, referencing the strong causal link between soda consumption and the

development of chronic diseases such as obesity, heart disease, cancer, and diabetes (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 2023). Examples of soda’s environmental impact are the large volume of plastic waste it produces, he continued, and the large amount of water that is used to grow soda’s corn and sugar beet ingredients. Baer noted that the soda industry provides many jobs and engages in social giving, recounting that some of his university students had received scholarships from soda companies. He also mentioned “pouring rights” contracts—funds paid to universities for exclusive rights to sell a particular brand of soda on campus—as well as government subsidies for the production of corn and high-fructose corn syrup. Legal issues play a role in the type of language that can be used on soda labels, he added, as well as whether warning labels are allowed.

Baer played a video of a soda advertisement to illustrate how advertising has been used to tell a story connecting that product to positive attributes related to Latino culture.2 The advertisement features a variety of people from Latino backgrounds who are asked to share their family name and the values they associate with being a person who bears that name. Attributes related to pride, hard work, and faith are shared, and eventually the people in the ad visit a food truck distributing soda cans bearing tattoos of Latino surnames. The people then press the cans to their arms, wrists, and necks to tattoo their bodies with their family names, and the ad ends by encouraging viewers to share the product with others. The power of the story in this ad, Baer asserted, is that it does not explicitly talk about soda, but the actors are drinking it throughout the ad, so it is associated with the cultural values expressed in the ad. It is difficult for obesity solutions to compete with this kind of compelling storytelling, Baer admitted.

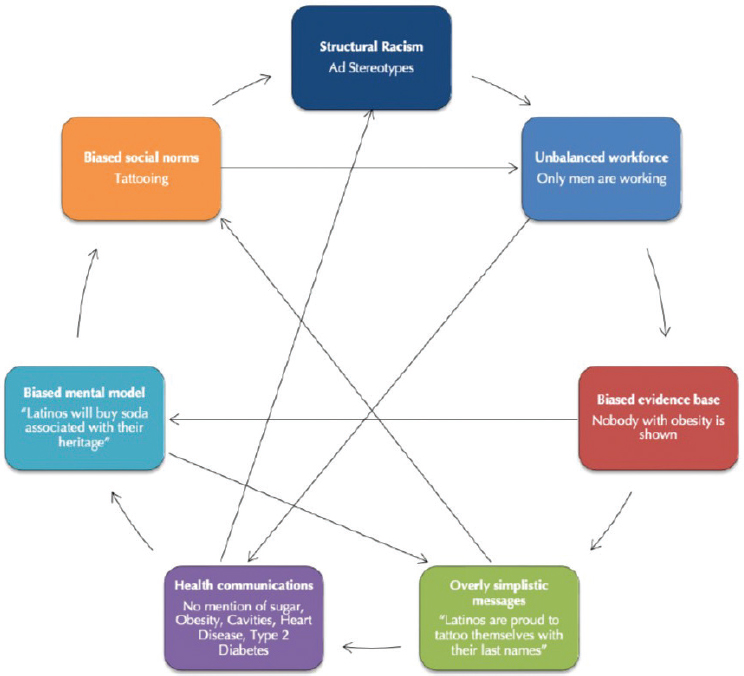

Baer applied the causal loop diagram that Lee had shared in the first workshop session (Figure 2-1, in Chapter 2) to analyze how characteristics of the advertisement map back to the drivers of obesity (Figure 4-1). He suggested that this diagram would be a useful teaching tool in helping students understand the deep layers embedded in advertisements that seem—at surface level—simple and lighthearted.

Baer returned to the hub-and-spoke concept to point out that one could replace the soda industry at the hub with another industry, such as tobacco, and apply the wheel to explore that product’s social, cultural, political, and economic impacts. Public health efforts face an uphill battle, he contended, because corporations that sell unhealthy products also provide jobs and other economic investments in society.

___________________

2 Video is viewable at: https://vimeo.com/138107682 (accessed January 23, 2023).

SOURCE: Presented by Neal Baer, April 19, 2022. Reprinted with permission.

PANEL AND AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Following the two presentations summarized above, Lee moderated a discussion with the speakers, which was followed by a round of audience questions. Topics addressed included communications training for health care professionals, targets for obesity solutions, framing messages about trade-offs between economic and health gains, leading with data versus emotion in public health communications, and navigating divisive weight-related topics when communicating about obesity.

Communications Training for Health Care Professionals

Many organizations provide communications training for health care professionals, Lindenfeld informed attendees, including online options. The Alda Center offers a training for health care leaders, she added, and noted

that a difference between science and health professions is that scientists typically receive no communications training. Health care professionals often receive this training, she said, but can find it difficult to apply when they are facing burnout. Lindenfeld shared that her institution is developing training for interprofessional teams that support patients, their families, and communities. Preliminary data suggest that using improv and empathy-based training helps care teams view each other with more compassion, she reported, and that a commitment to listening and empathy helps people become more resilient as part of a team.

Targets for Obesity Solutions

In response to Lee’s question about where obesity solutions should focus, Baer suggested that the soda industry deserves attention because of soda’s lack of nutritional value, causal link to adverse health outcomes, and role as a leading contributor of dietary added sugars in the United States. He suggested that health care professionals focus on helping soda drinkers switch to water, perhaps flavored with a squeeze of fruit, to lower their intake of added sugar and calories. More broadly, he asserted that public health professionals should help people understand that soda is not just about “sugar and water,” but is at the center of a complex corporate system.

An attendee asked a follow-up question about how to reconcile the idea that obesity results from multifactorial influences with Baer’s suggestion to focus on soda rather than broader food system actions that promote public consumption of unhealthy products. Baer affirmed that obesity is a multifactorial, complex problem and listed examples of its causal and contributing factors: food and beverage marketing targeted to minoritized populations, low prices and convenience of unhealthy food and beverage choices, and limited availability and lower affordability of healthy compared with less healthy foods. He appealed for communicating this complexity in a way that supports individuals in making healthier food choices.

Framing Messaging about Trade-offs between Economic and Health Gains

In response to a question about how to communicate the message that soda industry shareholders should accept short-term costs and losses (e.g., in jobs or stock returns) in return for long-term health benefits from reducing soda consumption, Lindenfeld proposed framing messages around the stakeholder group’s topics and issues of interest. Baer recalled the approach used by proponents of Philadelphia’s soda tax, which was successfully promoted as a strategy for generating revenue for early childhood

education instead of being framed as a health initiative. He reemphasized the opportunity to improve people’s diets through good storytelling and stressed the importance of multipronged approaches and local strategies for obesity solutions.

Leading with Data versus Emotion in Public Health Communications

Baer urged the use of emotion grounded in data when public health communications designed to share evidence-based messaging are developed. He maintained that whereas scientists and health care professionals may be compelled by data alone, it is important to integrate elements of curiosity and empathy into messages for the public. He asserted that curiosity is the gateway to empathy, adding that food and beverage advertisements typically embrace these elements in their storytelling but lack data.

Lindenfeld agreed and pointed to the difference between invoking emotion to manipulate people into taking action that does not serve their own interests and invoking emotion to engage people in compelling storytelling that serves to support them. She reiterated the effectiveness of using emotion to draw people in, but doing so in an honest way that shares facts and recognizes any scientific uncertainty that may exist. Training in science communication helps scientists and health care professionals strike this balance, she maintained, and she repeated her call for such training to be included in the pathway to becoming a scientist.

Baer shared his view that the public has an unrealistically high expectation for science to be definitive. It is incumbent on communications and public health professionals, he suggested, to help people understand that science evolves as more data become available and does so in a systematic manner.

Navigating Divisive Weight-Related Topics When Communicating about Obesity

An attendee observed that different beliefs exist with respect to the relationship of weight and obesity to health; for example, some believe that weight is not relevant to health, and obesity’s classification as a disease is embraced by some but rejected by others. Lindenfeld was asked to provide tips for promoting collaboration among people with varying views on these topics so they can communicate on issues on which they agree, such as the harms of weight bias and discrimination. She encouraged thinking about communication as a system in which players come to the table and discuss the perspectives of others instead of starting dialogue by insisting that a particular point of view is right while others are wrong. The conversation might focus on health more broadly to begin, she suggested, and gradually

shift to more divisive topics. Lindenfeld admitted that such conversations are not easy, but urged investment in greater capacity for collaborative communication so people with differing views can sit at the same table together and think through the issues.

Lindenfeld argued that, to compete with, for example, the large sums of money invested in food and beverage advertising, the public health community must go beyond its areas of disagreement and embrace the areas where it agrees, which she submitted are greater in number than areas of disagreement. Baer concurred, adding that some undergraduate students in his class do not want to use the word “obesity” because of what he called its “laden history.” Language matters, Lindenfeld remarked, because it is the frame from which people approach problems. If people are not in harmony in defining the problem from the outset, she said, “we are going to solve the problem we see and not the one we can find agreement on.”

It is important to respect how people feel about discussing these topics, Baer contended. He noted that students have expressed interest in reading memoirs such as Roxane Gay’s Hunger that describe people’s lived experiences with weight and body image issues. He stressed that examining the effect of social determinants of health on people’s lives helps bring empathy into the picture because it highlights how people’s day-to-day experiences and broader contexts of living are different from those of other people.