Translating Knowledge of Foundational Drivers of Obesity into Practice: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2023)

Chapter: 6 Engaging Communities to Address Structural Drivers of Obesity

The second (July 2022) workshop in the series began with an introductory session in which two speakers delivered presentations that set the stage for the workshop.

THE ROLE OF CAUSES OF AND CONTRIBUTORS TO OBESITY

Nikhil V. Dhurandhar, professor, Helen Devitt Jones endowed chair, and chairperson of the Department of Nutritional Sciences at Texas Tech University, discussed the distinction between causes of and contributors to obesity and the importance of addressing both at the systems level.

Dhurandhar began by defining “obesities,” using the plural intentionally to underscore his view that obesity is a collection of diseases with multiple causes, contributors, and clinical expressions. This complex nature of obesity could be compared with that of cancer, he suggested, which is not a single disease but a group of diseases with multiple causes, contributors, and clinical expressions. Dhurandhar contrasted this definition of obesity with the common belief that obesity is typically caused by eating too much and moving too little—that is, a result of poor dietary and lifestyle choices. He submitted that this view of the causes of obesity needs to be updated, comparing edema (swelling or water retention), which is caused not by drinking excess water but by impairment in the regulation of water balance, with obesity, which is caused by retention of excess energy in the body due to physiologic impairment in the regulation of energy balance.

Dhurandhar elaborated on the physiologic aspects of obesity, explaining that in a healthy state, body fat is maintained within a range. If a person’s fat storage is either insufficient or excessive, “nature doesn’t seem to like it,” he said, as indicated by impaired reproduction in either case (Friedman, 2011). He described the body systems that are responsible for hunger, satiety, and metabolic rate as examples of physiologic approaches to keeping fat storage in a healthy range. In people who develop obesity, he explained, these homeostatic systems are impaired or overwhelmed such that their bodies begin storing excess fat. Therefore, Dhurandhar concluded, an alternative view is that obesity is caused by the body’s inability to maintain fat within a healthy range.

Dhurandhar explained that this alternative view has its own set of causes and contributors to obesity (Dhurandhar et al., 2021). The causes in this case are intrinsic, he said, which means that they are within one’s body and can induce obesity in the absence of contributors, and while they are treatable, they also are not preventable. Examples include genetic defects in leptin or melanocortin-4 receptors; dysregulation of hormones that regulate thyroid function, hunger, and satiety; exposure to environmental chemicals and infections; and problems related to brown fat and fat oxidation.

The contributors to obesity in this alternative view are extrinsic—outside of a person—which Dhurandhar explained means they can lead to obesity in the presence of causes and are preventable, modifiable, and treatable. He cited as examples exposure to energy-dense foods, large portion sizes, and ultraprocessed food; insufficient sleep duration and poor sleep quality; poor psychological health; and food insecurity. These contributors appear to succeed in exerting effects on body weight when the energy balance mechanism with a person is impaired, he elaborated, noting that not everyone who eats large portion sizes develops obesity. A key implication of this view of obesity, he emphasized, is that if the contributors to obesity did not exist, future expressions of obesity would be reduced, an observation that, he contended, makes a compelling case for addressing those contributors at the individual, community, and national levels.

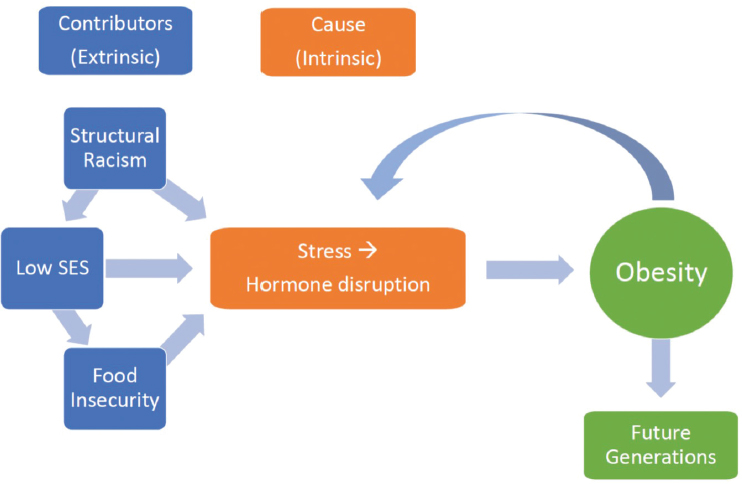

Dhurandhar shared an illustration of the interplay between causes of and contributors to obesity (Figure 6-1). In this graphic, contributors include structural racism, low socioeconomic status, and food insecurity, operating alone or in combination to trigger a physiological response within an individual whereby the stress that results from those factors leads to hormone disruption and ultimately to obesity. Obesity can in turn increase stress, Dhurandhar pointed out, and the cycle can continue and

NOTE: SES = socioeconomic status.

SOURCE: Presented by Nikhil V. Dhurandhar, July 25, 2022. Reprinted with permission.

may also increase the propensity of future generations to develop obesity. He explained that this illustration provides only one example of the many obesity-related loops and complex layers that can occur within an individual or a population.

Dhurandhar turned to his second key point: that while it is important to focus on prevention, treatment is imperative for the hundreds of millions of U.S. adults with overweight or obesity, and that treatment requires efforts to achieve substantial, sustained negative energy balance. As an example, he observed that if an individual needs 2,500 calories per day to maintain body weight, then a caloric deficit (e.g., a reduction to 2,000 or 1,800 calories per day) that is maintained for an extended period of time is necessary to optimize the likelihood of weight loss. Dhurandhar explained that this is why general, nonspecific weight loss suggestions—the approach usually taken with placebo (control) groups in trials of weight loss drugs—typically fail to produce meaningful weight loss. Control groups, he elaborated, usually receive general counseling about dietary and physical activity strategies for reducing energy intake and increasing energy expenditure, but even though participants are motivated enough to enroll in structured research opportunities led by academic researchers, they generally lose only 1–2 percent of body weight after 1 year.

Dhurandhar explained that such unstructured weight loss interventions typically fail to produce meaningful weight loss because individuals are unfamiliar with the caloric values of both food and physical activity, as well as with the body’s calorie requirements and how they can vary from day to day. Moreover, the body resists weight loss, he pointed out, with physiologic and metabolic adaptations to weight loss often challenging individuals’ attempts to lose weight (Leibel et al., 1995; Sumithran et al., 2011).

Dhurandhar moved on to his third and final point: meaningfully addressing existing obesity and minimizing or preventing its further expression requires providing individualized, structured, wide-scale treatment. Approaches that aim to modify only one contributor to obesity are ineffective on their own, he stressed, because many other simultaneously operating contributors will continue to perpetuate the problem. He presented a series of examples of how supporting both individual and systems changes can synergistically address obesity more effectively and on a wider scale.

First, Dhurandhar suggested that facilitating obesity management in individuals could include addressing insufficient quantity or quality of sleep. A corresponding systems change to support and facilitate those individual-level efforts is to address the broader contributors that lead to disturbed sleep, such as a community’s noise level.

A second example, Dhurandhar continued, is to facilitate obesity management in individuals through a personalized diet for negative energy balance, which could be supported by certain lifestyle, pharmacological,

and/or surgical approaches. The corresponding systems change is to promote a conducive environment for achieving and maintaining a negative energy balance, such as by increasing awareness of obesities, providing screening and access to health care, and improving the availability and accessibility of healthier food options that are both appetizing and affordable.

Dhurandhar described his third example as similar to the second, except the focus is on a personalized plan to promote energy expenditure. The corresponding systems strategies are to increase awareness of the role of physical activity and improve access (perhaps through policy changes) to physical activity opportunities.

Dhurandhar’s fourth example involves making obesity management widely available for individuals, such as by improving access to obesity specialists and relevant allied health care professionals, such as registered dietitians. At the systems level, Dhurandhar suggested incorporating obesity management training in education for health care providers and broadening access to and insurance coverage for providers that offer obesity management care.

As a final example, Dhurandhar suggested that while other risk factors exist, obesity expression could be minimized or prevented in at-risk individuals by preventing them from gaining or regaining weight through identification of their intrinsic risk factors, such as by screening for gene defects or hypothyroidism. At the systems level, he called for minimizing such risk factors for obesity expression as structural racism, food insecurity, and economic instability.

Dhurandhar summarized his remarks by reiterating that obesities have (intrinsic) causes and (extrinsic) contributors. Effectively treating an individual’s obesity requires structured, personalized treatment, he stressed, whereas addressing obesity at the community and national levels requires effective, wide-scale obesity treatment for individuals accompanied by supporting systems changes. Necessary as well, Dhurandhar reminded the audience, is preventing excess weight gain or regain in at-risk individuals, along with minimizing systems-level risk factors for obesity expression.

EFFECTING OBESITY SOLUTIONS THROUGH COMMUNITY SYSTEMS CHANGE

Shiriki K. Kumanyika, emeritus professor of epidemiology in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and research professor in the Department of Community Health and Prevention at Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health, discussed how to effect obesity solutions through community systems change. In her view, Dhurandhar’s framing of issues as causes and contributors helps clarify that solutions are not “either/or,” but “both/and.” There is no competition

between prevention and treatment strategies, she asserted, or between individual- and population-level solutions, because in each case, both are needed. “Both/and” framing also emphasizes the importance of obesity solutions that mitigate factors outside individuals’ direct control, she added, and underscores the potential power of collective actions to effect population-level solutions. Solutions that work for individuals should not be confused with those that work for populations, Kumanyika stated, referencing Dhurandhar’s series of examples illustrating differences between the two.

Kumanyika referred to the Roundtable on Obesity Solutions’ systems map of obesity’s drivers and solutions (Figure 1-1, in Chapter 1). She emphasized the array of subsystems within the larger obesity system that either perpetuate or alleviate the problem; reiterated the Roundtable’s three priority areas of health communication, structural racism, and biased mental models and social norms; and pointed to other factors that appear on the map in more than one place (e.g., physical activity, nutrition, food systems, food policies). These factors, she maintained, are potential candidates for taking action, and she contended that an exquisite understanding of obesity systems is effective only when it is translated into action. Kumanyika recounted that the first workshop in the 2022 series had explored strategies for translating the systems map into action, and she explained that this second workshop would continue the discussion with a focus on engaging communities to address structural drivers of obesity. The discussion, she said, would address the relevance and impact of power within communities, approaches to community engagement, and barriers to and opportunities for solutions at the community level.

Kumanyika offered four caveats for thinking about community power and community-level obesity solutions. First, she posited that communities should be approached as complex systems in which contributors to obesity are interrelated and dynamic. Second, she suggested that, whereas community-level solutions are most proximal to individuals and families, contributors at this level may be driven by upstream factors such as state or national policies. Third, she stated that it is important for community-level solutions to be present- and future-oriented and also proactive to address historical factors that have contributed to problematic structural pathways. These pathways need to be strategically destabilized, she asserted, without disrupting societal function. Her fourth caveat was that just as individuals are affected differently by obesity’s causes, communities are affected differently by obesity’s contributors.

With respect to the relevance or impact of power as a leverage point for action, Kumanyika suggested that one could seek this leverage point in three different aspects of a system (i.e., community): in the parts of the system (diversity in the types and makeup of communities); in the relationships

of different structures within the system; and in patterns of the system where strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, or threats to understanding and tackling obesity could be addressed.

Finally, Kumanyika shared an iceberg metaphor to illustrate the root causes, structures, policies, and patterns that lead to obesity at the individual and population levels.1 This visual has been used as a model of the conditions for system change, she noted, and focuses on elements that must be addressed to promote structural change, relational change, and transformative change.

___________________

1 For more information about the iceberg metaphor, see figure 4-3 in National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2021. Integrating Systems and Sectors Toward Obesity Solutions: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25766.

This page intentionally left blank.