Translating Knowledge of Foundational Drivers of Obesity into Practice: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2023)

Chapter: 13 Progress in Obesity Solutions: Sociocultural Systems

The fourth and final session of the October workshop addressed progress in obesity solutions in sociocultural systems. Stephanie A. Navarro Silvera, professor of public health at Montclair State University, moderated the session’s three speaker presentations and ensuing discussion and question-and-answer period.

MEASURING STRUCTURAL RACISM FOR HEALTH POLICY

Tongtan (Bert) Chantarat, research scientist at the Center for Antiracism Research for Health Equity at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, discussed the Center’s effort to measure structural racism. He began by defining structural racism as “the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination, through mutually reinforcing inequitable systems (in housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, criminal justice, and so on) that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and the distribution of resources, which together affect the risk of adverse health outcomes” (Bailey et al., 2017). Chantarat stressed that this definition conveys a situation in which many dimensions work together and reinforce each other to create an outcome, and he pointed to this as the essence of structural racism—a system, rather than an individual component of a system, that drives poor health among racialized groups. Developing and applying approaches that operationalize and measure structural racism as a multidimensional determinant of health is an important step in working toward change, he added, and he shared a resource for a novel, latent construct approach he and his colleagues developed to measure structural racism for the purposes of achieving health equity (Chantarat et al., 2022).

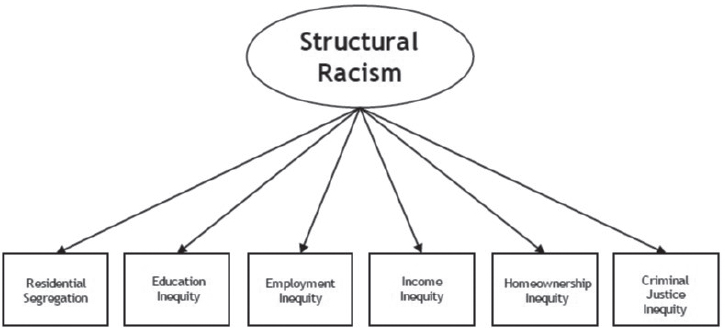

Chantarat called for measuring structural racism as a whole that is bigger than the sum of its parts—such as residential segregation, work inequity, and racialized policing—that contribute jointly to health inequities. The latent construct approach his team applies to measuring structural racism uses latent class analysis, he explained, which is often used to measure multidimensional entities such as personality type (which comprises multiple personality traits). Each dimension of structural racism (e.g., Figure 13-1) is like a personality trait, he said, clarifying that his team’s approach allows researchers to identify qualitative, multidimensional typologies. Chantarat acknowledged that the dimensions of structural racism shown in the figure are by no means exhaustive and that his team’s future work will incorporate additional dimensions.

Chantarat described his recent study of birth inequities, in which multidimensional structural racism was used to predict birth outcomes for Black

SOURCE: Presented by Bert Chantarat, October 25, 2022. Reprinted with permission.

and White Minnesotans (Chantarat et al., 2022). The study examined two research questions:

- Do risks of preterm birth (PTB), low birthweight (LBW), and small-for-gestational-age (SGA) birth differ among White, U.S.-born Black, and foreign-born Black pregnant people exposed to the same structural racism typology (i.e., residence in an area with the same pattern of structural racism)?

- Do risks of PTB, LBW, and SGA differ for pregnant people of the same racial background in different structural racism typologies?

Chantarat explained that the study relied on birth record data from the Minnesota Department of Health for approximately 20,100 White, 3,000 U.S.-born Black, and 5,000 foreign-born Black individuals. He described a type of analysis called the Vermunt three-step approach, used to identify a pattern and link it to an outcome of interest. That analysis produced three structural racism typologies (varying patterns of residential segregation, education inequity, employment inequity, income inequity, homeowner-ship inequity, and criminal justice inequity), he reported, which were each linked to birth outcomes. The researchers found that age-adjusted risk for PTB, LBW, and SGA was lowest for White pregnant people in all three typologies, and that for people in the same racial group exposed to different patterns of structural racism (U.S.-born Black versus foreign-born Black individuals), the same level of risk was observed.

With respect to policy implications, Chantarat explained that the dimension of education inequity was found to be intricately linked to various dimensions that affect structural racism and that structural racism cannot be classified simply as high or low across all dimensions based on his study findings. Because of these intricate interconnections among dimensions of structural racism, he maintained, targeting one dimension (e.g., addressing education inequity) may not be the most effective strategy; rather, multisectoral policy interventions are needed to address all dimensions and effectively eliminate racial inequities. It is necessary to dismantle the whole system, he stated, and not one dimension of structural racism at a time.

ENGAGING COMMUNITIES TO ADDRESS HEALTH INEQUITIES

Kierra S. Barnett, research scientist in the Center for Child Health Equity and Outcomes Research at the Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, discussed engaging communities to address health inequities. She began by acknowledging that engaging communities is not easy, and often takes more time than funders, policy makers, or even researchers themselves would prefer. Although it can feel daunting to invite other opinions into one’s work, she recognizes that community input is a key ingredient for success.

Barnett described three benefits of engaging communities. The first relates to the fact that context matters, and unpacking the complexity of the systems in which people live calls for uplifting and seeking to understand people’s lived experiences. Moreover, Barnett added, social determinants of health intersect and overlap differently across individuals and populations, and impact outcomes for those groups in different ways. She stated that talking with community members can help researchers understand their values, needs, and priorities so that the research can be designed accordingly.

As a second benefit of engaging communities, Barnett pointed to how it helps researchers improve their work because talking with people about their lived experiences helps refine research questions, measures, and/or potential solutions. Barnett shared an example of how researchers held focus groups with Black women to build a framework for describing how structural racism impacts reproductive health (Chambers et al., 2021). Community engagement also helps identify a community’s assets and strengths, she observed, such as certain resources and allies, that can be leveraged and promoted to build better solutions.

Third Barnett cited as a benefit of engaging communities that it increases community buy-in. The goal is to build trust with a community, she clarified, yet a history of injustice in most marginalized communities has led to distrust of both the medical and research communities. According to Barnett, rebuilding that trust requires authenticity, which she suggested

researchers can demonstrate when they explain the purpose of their research and describe how community input will be used to better inform it. Once trusting relationships have been built, she continued, engaging the community will increase their receptiveness to the researchers’ work, and community members will be more likely to engage in an intervention or program when they feel as if they have been involved in the process of developing it.

Barnett next described what entities and individuals can be engaged in communities, which she said fall into three categories: organizations or institutions with which researchers work, which typically hold the power for developing solutions to health inequities; stakeholders or champions in the community, who can provide windows into the community’s lived experiences; and community members, who can share their own daily experiences and provide opinions about other community members’ experiences. Barnett advocated engaging all three groups in any community-based research.

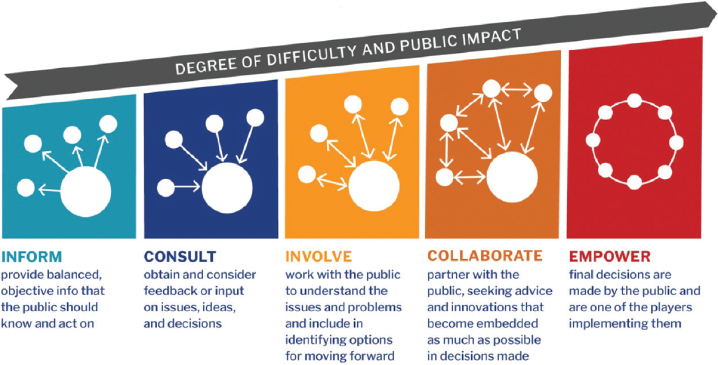

Barnett moved on to describe a community engagement continuum that can be used to illustrate the ways in which researchers can engage all three of these community groups (Figure 13-2).

The degrees of both difficulty and public impact increase as one moves from left to right along this continuum, she explained. She contended that researchers often remain in the “inform” and “consult” categories, which involve simply sharing information with community members in a one-way fashion and obtaining and considering their feedback and input, while final decisions rest with the research team. In the next category, “involve,”

SOURCE: Presented by Kierra Barnett, October 25, 2022. Harvard Catalyst (2022) (adapted from Principles of Community Engagement - Second Edition). Reprinted with permission.

information sharing becomes bilateral, perhaps in the form of a community advisory board. The research team still makes final decisions, Barnett said, but board members provide feedback directly to the team on those decisions. She explained that the next category, “collaborate,” differs from “involve” in that the community is engaged from square one to cocreate each stage of the research process, not just when a final product is nearly complete, and becomes embedded to the extent possible in the decisions made. The final category, “empower,” is where decisions are made by the community and often implemented by the community as well.

Barnett ended her presentation with an example of how her team engaged the community (Barnett et al., 2022). The goal was to understand the perinatal lived experiences of women of color to inform public policy and strategic planning for the City of Columbus. Key players included Nationwide Children’s Hospital; CelebrateOne, a maternal and child health–focused city agency; DesignImpact, a community-centered design organization that engages other organizations to bring community voices to its work; and peer researchers, women from the community with lived experiences who were trained to engage in research. Barnett’s team cocreated a focus group facilitation guide with peer researchers for use in eliciting experiences from community members, and the peer researchers facilitated the focus groups. Initial focus group summaries were verified by the peer researchers, and Barnett’s team then completed a detailed qualitative analysis of the focus group data, which ultimately informed the strategic plan for the City of Columbus. In Barnett’s view, the project was an example of “collaborate” on the community engagement continuum because all players had important roles throughout the process.

In closing, Barnett urged thoughtful consideration of how community engagement will look for a given effort. “Inform” and “consult” are good places to start, she said, and she encouraged moving farther along the continuum. She shared her hope for future examples of systems of empowerment that allow community members to have control over decisions and their implementation.

LISTENING TO THE COMMUNITY: ENGAGING IN COMMUNITY-BASED PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH

Ijeoma Opara, assistant professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Yale School of Public Health and director of the Substances and Sexual Health (SASH) Lab, discussed the value of multidisciplinary collaboration in community-based research for identifying meaningful solutions. She opened with a quote from a woman who intentionally gained excess weight as a strategy for avoiding sexual assault because “boys don’t like fat girls” (Gay, 2017). Opara shared that this quote drove her to

think about obesity through a different lens and to ask whether obesity or something else is the core, underlying issue. For example, the issue may be how obesity is defined (e.g., body mass index [BMI]), trauma, stress and mental health, access to healthy foods, or neighborhood conditions such as environmental racism.

Opara described key objectives of her lab’s work on substance abuse and sexual health, which she explained is guided by community-based participatory research (CBPR) and an antideficit approach to prevention for adolescents of color. SASH aims to stand against anti-Black racism and oppression through strengths-based research and youth advocacy, she explained, and to use community-engaged strategies to prevent substance abuse and improve sexual health outcomes. This work, she said, feeds into broader goals for identifying and reducing racial disparities in health in the United States. According to Opara, CBPR and community-engaged work are critical both for eliminating health disparities and for understanding the diverse lived experiences of people in various communities.

Opara elaborated on the characteristics of CBPR, which she described as an approach—not a research method or design—for conceptualizing a study and working collaboratively with a community at each stage of the process. The work takes place in the community setting, she elaborated, and is done with and immersed in the community, not imposed on the community. As researchers seek to understand what community members face on a daily basis, she added, it may become clear that certain solutions to the problems they are studying may be more or less realistic for the community to implement. Opara urged researchers to see community members as real people, not just data points, who are looking to partner with them to solve health-related problems.

CBPR emphasizes the importance of colearning, Opara continued, noting that researchers tend to approach communities with a problem-solving mentality, but instead should remain humble and value community partners as experts in their own lived realities. She encouraged researchers to identify community assets and strengths, such as factors that have contributed to resilience. Her goal, she said, is to complete a project with assurance that the solutions developed in partnership with the community are sustainable and that the problems addressed by those solutions are in the past because the community is empowered to sustain the solutions.

Opara explained that CBPR calls for equitable partnerships whereby community members have equal decision-making authority for research decisions that affect the community. She took the concept a step further by suggesting that community members could identify the issues in their communities instead of researchers coming in to tell the community what issues would be targeted in their research. Community members may not prioritize issues the same way that researchers would, she pointed out, and may not

even perceive an issue identified by researchers as a problem for their community. Opara urged researchers to be prepared to pivot to address issues raised by the community, particularly if those issues were not part of their initial research agenda.

Opara concluded her description of CBPR by stating that it acknowledges mistrust of researchers stemming from the country’s history of unethical research practices carried out on people of color. She explained that in her work with urban communities of many Black and Hispanic youth, she maintains an awareness of this mistrust, explains to communities her purpose for engaging them in her research, and describes her own experiences growing up in an urban community. Then she uplifts their stories and invites them to be an equal partner in the work, committing to them that data and results generated by the research will come back to them to empower and benefit the community. As the research proceeds, Opara stressed, CBPR can gradually restore community members’ trust in the researchers.

Opara transitioned to describing three strategies researchers can use when engaging in CBPR. The first is to think about planning, which she suggested framing as “What does this community need from me?” instead of “What do I need from them?” Researchers tend to be focused on collecting the data necessary to conduct an analysis, she observed, and to enter a community for this single purpose and promptly leave when enough data have been collected. She contrasted this approach with researchers having a mindset that they are benefiting from the data and the community’s vulnerability, and in turn thinking about how to give back to the community. Planning should be driven by the community needs and wants, she asserted, and she encouraged investigators to allow their preconceived research questions to evolve and their planned interventions to be adapted. If the community does not have full input into the process and the proposed intervention, she cautioned, it will not be successful.

Opara cited as a second strategy fostering relationships with communities. The right way to gain insight from a community, she submitted, is to plan or participate in a town hall meeting or attend a coalition meeting to learn what issues are pressing in the community and what relationships might be important to cultivate. Establishing community advisory boards is a great idea, she said, but cautioned that their utility can be limited depending on their membership composition and leadership. For example, she pointed out, investigator-led meetings are different from community-led or coled meetings. The timing, location, and frequency of meetings are important as well, she continued, because they must be planned to allow engagement with community members most impacted by the solutions to be developed by the project. Opara urged against

sole reliance on community advisory boards and encouraged concurrent discussions with community members, other coalitions, and community activists and organizers.

Third, Opara discussed the use of community-level data to empower communities. She appealed for CBPR scholars to cultivate active citizenship by bringing the data collected in research back to the community to help its members understand how they can use those data to create positive change for the community’s benefit. She shared an example of her work using data to end substance misuse among youth in Paterson, New Jersey. With the community’s input and participation, the researchers collected qualitative and quantitative data to examine substance use rates in the community and understand the experiences of youth with respect to the high volume of liquor stores in their community. Residents brought the data to the city council and advocated for closing some of the liquor stores. The combination of data and community members’ voices led to the passing of a city ordinance that regulated the liquor stores in Paterson, Opara reported, citing this outcome as an example of what she called “the beauty of the power that community members have when we work collaboratively with them.”

In closing, Opara summarized key takeaways with respect to obesity solutions. She called for investment in CBPR, which she said is highly rewarding and meaningful despite its challenges and the long time that it takes to cultivate the relationships necessary to develop community-specific solutions. One-size-fits-all approaches will not work, she maintained, but an approach that works in one community may be suitable for adaptation in another. She reiterated the importance of identifying community assets and strengths and allowing community members to identify their issues and potential solutions. Researchers may perceive obesity as an issue in a community, she said as an example, whereas residents may perceive the issue as body image, diabetes, or access to healthy foods and safe places to be active. Actively listening to the community and understanding the contextual, historical, and sociocultural factors that contribute to its obesity situation are important, Opara stressed, for understanding why people engage in certain behaviors and for informing potential solutions.

PANEL AND AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Following their presentations, the three speakers participated in a panel discussion and answered participants’ questions. They discussed improving measures of structural racism and engaging communities in developing measures, modifying academic value systems for community-engaged research, and approaches for engaging communities authentically.

Improving Measures of Structural Racism and Engaging Communities in Developing Measures

Chantarat observed that researchers often create measures and indexes without considering how they could inform policy. His team’s measure of structural racism identifies ways to intervene, which he suggested is a potential goal for others to keep in mind as they create measures.

Barnett suggested that talking to community members is an initial step toward developing measures of structural racism. For example, they could be asked for their opinions and thoughts about the concept, which she pointed to as a way to involve community members in the formative stages of research when research questions are formulated. Opara observed that researchers often have a “hyperfocus” on measurements and data collection when defining problems, and urged the field to stop and recognize when sufficient data are available to move to the next, critical step of developing solutions. She also shared her view that sufficient data are available to demonstrate that racism contributes to inequities, and that people and institutions should be held accountable for perpetuating it.

Barnett built on Opara’s comments regarding what “evidence-based” means with respect to developing solutions. She observed that researchers want to find something that is statistically significant, and contended that as a result, they place less value on community voices, whose statistical significance is difficult to determine. Barnett suggested that a paradigm shift is needed whereby researchers view community-provided solutions as evidence based.

Modifying Academic Valuation Systems for Community-Engaged Scholarship

Silvera suggested that community-engaged research requires a greater investment of time than, for example, conducting a cross-sectional study, and pointed to this as a challenge for newer investigators who are trying to build up their resumés and advance professionally. She asked the speakers to comment on how the paradigm may need to shift to change the way community-engaged work is viewed and valued.

Opara shared her perspective as a scholar on tenure track who is trying to maintain research productivity while also engaging with communities. She explained that she spends a great deal of time cultivating and maintaining relationships. Thus because she also must dedicate time to writing, her overall time investment in academic work differs from that of colleagues who do not focus on community-engaged research. Publishing scholarship is important not only for pursuing tenure, Opara stressed, but also for informing and advancing the field of community-engaged studies. She also referenced the significant amount of time she spends collaborating

with researchers doing similar work so they can learn from each other and inform each other’s work. This collaboration strengthens the quality of the literature produced, she maintained, which is important as a channel for uplifting underrepresented voices and their strengths and advancing the field’s use of intersectionality in quantitative research.

Opara reported that she has observed a shift in academia whereby some departments are recognizing the time demands and value of community-engaged scholarship and realizing that it should be evaluated differently from more traditional research pursuits with respect to advancing toward tenure and promotion. That kind of shift will encourage more researchers to pursue this type of work, she suggested, and continue to increase the value of this research from the perspective of institutions. Barnett agreed that the relative value placed on different scholarly activities needs to change. She suggested that community-engaged scholars may not be able to produce publications at the same rate as other scholars, but that their contributions to the field should be valued similarly and recognized for the tangible changes they are helping to produce in communities.

Approaches for Engaging Communities Authentically

Opara highlighted the importance of exploring and defining one’s purpose and motivation for engaging with a particular community. She observed that well-meaning individuals without ties to a community may express a desire to “help poor people,” and urged those individuals to unearth and examine any biases they may have toward the community. According to Opara, failure to eliminate the bias and stereotypes that one may hold toward a community of people can compromise the ability to work collaboratively with the community, respect its members’ opinions, and provide honest feedback and solutions. She cautioned against doing “missionary work” with communities, which she said are resilient and will continue to press on with or without the intervention of academic institutions. It is less essential for researchers to have a direct tie to the community, she added, than it is for them to acknowledge having a different perspective from that of the community, to adopt a humble approach, and to have a genuine desire to partner and learn mutually through meaningful collaboration.

WORKSHOP WRAP-UP AND CLOSING REMARKS

Bruce Y. Lee, professor of health policy and management at the City University of New York Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy and executive director of the PHICOR (Public Health Informatics, Computational and Operations Research) initiative and Center for

Advanced Technology and Communication in Health, provided closing remarks that included key takeaways from each workshop in the series.

Lee stated that the first (April 2022) workshop, “Shifting the Paradigm: Targeting Structures, Communications, and Beliefs to Advance Practical Strategies for Obesity Solutions,” highlighted the existence of reinforcing systems that perpetuate problematic structures and environments that in turn contribute to obesity (Figure 2-1 in Chapter 2). Simple “Band-Aid” solutions are not effective in such a complex situation, he observed, as they often fail to address root causes of the problem and do not appreciate the multisector complexity of the obesity epidemic.

Lee summarized the second (July 2022) workshop, “Engaging Communities in Addressing Structural Drivers of Obesity,” by pointing out that it explored strategies for actively engaging communities to develop obesity solutions. He clarified that a community is not necessarily constrained to a particular geographic area; rather, it is any set of people who are connected in certain ways. Communities are complex, heterogeneous systems, he observed, where power dynamics are key drivers of community norms and policies; therefore, it is critical to empower different stakeholders to effect change.

The third (October 2022) workshop, “Defining Progress in Obesity Solutions through Structural Changes,” Lee stated, focused on methods for assessing progress in addressing structural drivers of obesity lest positive change proceed overly slowly or not at all. He reminded attendees that measures of progress are critical because it is not possible to fix something that cannot be or has not been measured, and because failure to measure a problem may allow it to grow beyond its capacity to be adequately resolved. Furthermore, he maintained, one measure cannot tell the whole story; a systems approach to developing a complex series of measures is needed to capture progress in the various sectors of the systems that influence obesity.

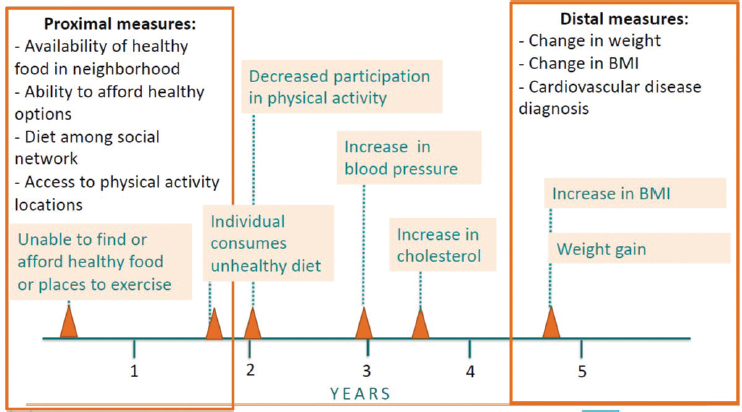

Lee elaborated on the third workshop by summarizing characteristics of measures and approaches to measurement that he believes are needed, beginning with measures that target root causes of obesity in different communities. He also emphasized the importance of capturing proximal measures (e.g., neighborhood availability of healthy foods) that can provide earlier feedback on the effectiveness of an intervention relative to waiting for longer-term outcomes such as changes in BMI to materialize, and provide the opportunity to course correct before it is too late to do so (Figure 13-3).

Lee also highlighted the need for measures that promote long-term, sustainable solutions, as well as measures that cut across multiple scales of influence (e.g., genetic, physiologic, behavioral), social/group dynamics, physical and built environments, and societal forces (Lee et al., 2017). These scales interact with each other, he pointed out, in ways that may not

NOTE: BMI = body mass index.

SOURCE: Presented by Bruce Y. Lee, October 25, 2022. Reprinted with permission.

be obvious. Finally, he stressed the importance of measures that are accessible and understandable to diverse stakeholders, given that public health problems are ultimately societal, not individual, matters.

In conclusion, Lee emphasized that obesity—like many other public health problems—is a manifestation of broken systems. Therefore, he explained, approaches similar to those used in obesity solutions can be applied to various types of public health problems, and solutions for obesity may also address other public health and social problems that are perpetuated by common contributors.

This page intentionally left blank.