Translating Knowledge of Foundational Drivers of Obesity into Practice: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2023)

Chapter: 12 Progress in Obesity Solutions: Health Care Systems

The third session of the October workshop addressed progress in obesity solutions with respect to health care systems. Sean Phelan, associate professor and head of social and behavioral sciences in the Division of Health Care Delivery Research and the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery at the Mayo Clinic, moderated the session, which featured two speaker presentations followed by a panel and audience discussion.

INTERSECTIONALITY, OBESITY, AND UNDERREPRESENTED PATIENTS

Said Ibrahim, senior vice president of the medicine service line for Northwell Health and chair of the Department of Medicine and David J. Greene professor of medicine in the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, discussed osteoarthritis care as an example of the intersectionality of obesity/high body mass index (BMI) and the use of treatment for this condition in underrepresented communities. He also elaborated on the challenge that many health systems face in providing comprehensive weight management and obesity care.

Ibrahim began by noting that osteoarthritis is the leading cause of disability in older adults, explaining that the increasing prevalence of this condition reflects both the aging of the population and the rising prevalence of obesity (Ali et al., 2021; Wallace et al., 2017). When medical and behavioral management—i.e., nonsurgical options—fail, he said, elective joint replacement of the knee or hips is a viable option. He noted that this option is the fastest-growing elective surgery in the United States, and added that Medicare pays for 60 percent of all the elective knee and hip replacements performed nationwide (AHRQ, 2018).

Ibrahim reported that African American patients and patients from other racial/ethnic minority groups are 40–50 percent less likely than White patients to undergo elective knee or hip replacement, despite similar or higher (for knee osteoarthritis) prevalence of the condition in African American populations and expansion of the procedure in the United States overall (Escarce et al., 1993; Hoaglund et al., 1995; Wilson et al., 1994). Ibrahim contended that high BMI or obesity confounds treatment of these patients and their access to joint replacement. The average BMI for a patient who undergoes knee or hip replacement in the United States is 35, he said, adding that surgeons are less likely to offer the procedure to patients with a BMI above 40 because of concerns about complications. He pointed, however, to a lack of evidence demonstrating that higher BMIs are associated with higher surgical complication rates. The prevalence of obesity varies by race/ethnicity, Ibrahim continued, and he suggested that patients from underrepresented populations who have high BMIs are stigmatized

and experience unequal access to care, including knee or hip replacement (Brock and Kamath, 2019; Rodriguez-Merchan, 2014).

Ibrahim referenced a recent study examining the association between Medicare’s mandatory bundled payment program for joint replacement and receipt of elective hip or knee replacement for White, Black, and Hispanic Medicare patients (Kim et al., 2021). This study found that bundled payments were associated with increased receipt of elective hip or knee replacement among Hispanic beneficiaries, decreased receipt among Black beneficiaries, and no change in receipt among White beneficiaries. Ibrahim raised concern that the bundled payment program and financial incentives and pressures may lead surgeons to become more selective in whom they operate on because they want to avoid complications. This selectivity may in turn result in surgeons avoiding patients with a high BMI, a condition more prevalent in minority patients, which he said would explain why these patients are less likely to receive the surgery. Because the surgery is elective, it involves a great deal of discretionary decision making, he maintained, and he highlighted this issue as an exemplar of the intersectionality of obesity and certain demographic factors.

Ibrahim shifted to discussing the challenge faced by health systems seeking to establish a comprehensive solution for weight management and obesity. He shared insights from his own health system, Northwell in New York City, which comprises more than 20 hospitals and 850 ambulatory care centers that serve a highly diverse patient population with a high prevalence of obesity and weight-related conditions. According to Ibrahim, Northwell is still struggling to establish a comprehensive strategy for delivering care for this population, although it has a weight management center, a bariatric center, and other relevant programs. He pointed out, however, that these programs are not under a single umbrella, and he called for more coordinated, seamless care for weight management.

A related challenge, Ibrahim continued, is that the health system does not have a plan for helping patients prevent overweight and obesity. Family care offices are probably the place for such counseling, he suggested. He also raised the question of how best to care for patients who need weight management interventions (which may involve prescription drugs). He concluded by stating that a systems approach is needed to provide care for patients with obesity.

COMPLEXITIES AND CONSEQUENCES OF OBESITY

Fatima Cody Stanford, obesity medicine physician-scientist and associate professor of medicine and pediatrics at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, shared her perspective on the role of health care systems in progress on obesity solutions.

Stanford began by underscoring the complexity of obesity as a chronic disease, describing it as a multifactorial disorder with links to genetic, environmental, developmental, and behavioral causal and contributing factors. Whereas dozens of factors both inside and outside of a person contribute to obesity by influencing energy intake, energy expenditure, or both, Stanford contended that some factors receive a great deal of attention, while others are neglected. She shared a diagram illustrating several categories of the factors contributing to obesity, along with examples of each: environmental (pressures on physical activity, such as sedentary time and built environment factors); biological/medical (age-related changes such as menopause, genetics, and weight gain–inducing drugs); maternal/developmental (maternal obesity, gestational diabetes); economic (food advertising); food- and beverage-related behavioral/environmental (large portion sizes, eating away from home); psychological (stress); and social (weight bias and stigma) (Obesity Society, 2015).

Stanford maintained that the brain, particularly the hypothalamus, is the most critical weight-regulating organ. That region of the brain, she explained, receives signals from different organs and parts of the body that direct how much to eat and store, which helps explain the complex pathophysiology of obesity. She referenced leptin as an example of hormone signaling from fat cells, noting that it can act down different physiologic pathways and result in either lean expression or high expression of fat tissue in the body (Walley et al., 2009).

Stanford moved on to discuss her views on BMI, which she said was derived from Belgian statistician Adolphe Quetelet to determine normal weight status for Belgian soldiers in the 1800s. The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company adopted Quetelet’s index in the 1930s to determine what weight status was considered ideal, she continued, and it evolved into the BMI metric used today. That metric is “indeed flawed,” Stanford argued, noting that the use of BMI became part of eugenics, the study of arranging reproduction within a human population to increase the occurrence of heritable characteristics regarded as desirable, which was discredited during the 20th century as unscientific, discriminatory, and racially biased.

At present, Stanford continued, BMI is used to determine one’s weight status and is featured in electronic health records and guidelines from public health agencies and medical societies. The problem, she asserted, is that BMI alone does not define one’s health. To support this statement, she pointed out that some patients at the higher end of the BMI spectrum may be in better overall health than some with “normal” weight status. She noted further that BMI cutoffs have been adjusted for Asian populations, but that such adjustments have been suggested but not formally adopted for other racial/ethnic groups in the United States, such as Black and Hispanic people. She cited an analysis that recalculated the BMI threshold by sex and race/ethnicity based on association with metabolic disease. According to that analysis, Stanford reported, the cutoff for obesity is at, for example,

a BMI of 27 for White women and 31 for Black women for hypertension as a comorbidity (Stanford et al., 2019). These differences have implications, she stressed, for racial/ethnic comparisons of the BMI-based prevalence of obesity and severe obesity (Hales et al., 2020).

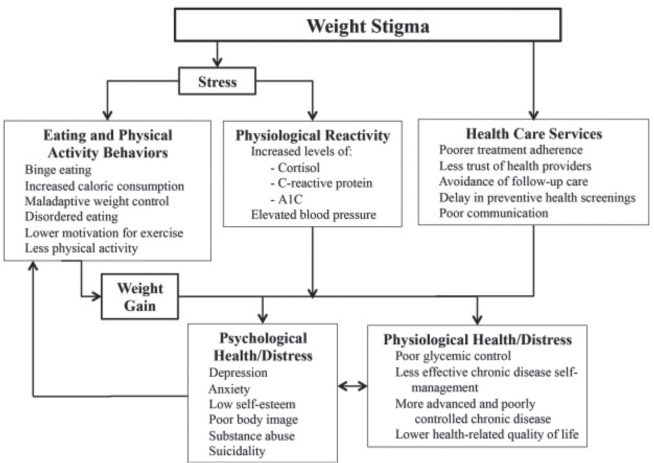

Stanford transitioned to discussing weight stigma—which she said is perpetuated by health systems—and its relationship to obesity treatment. She noted that physicians lack education about the disease of obesity, although the American Association of Medical Colleges released core competencies for obesity treatment in early 2022. Stanford referenced data indicating that about 80–90 percent of physicians have strong biases toward patients with excess weight, which may be coupled with racial biases (Puhl et al., 2016). She added that weight stigma influences stress and, in turn, eating and physical activity behaviors, leading to adverse health effects. According to Stanford, weight bias compromises health services in ways that result in poor treatment adherence, diminished trust in health care providers, avoidance of follow-up care, delays in preventive health screenings, and poor communication. These outcomes, she stated, are associated with adverse physiological (e.g., poor chronic disease control) and psychological (e.g., depression and substance abuse) effects (Figure 12-1).

According to Stanford, the United States—which she commented ranks 14th out of 200 countries in the prevalence of obesity—falls short in its

SOURCE: Presented by Fatima Cody Stanford, October 25, 2022. Puhl et al. (2016). Reprinted with permission.

treatment of obesity as a chronic disease (World Obesity Federation, 2022). She reported, for example, that only 1 percent of individuals who meet the criteria for treatment of obesity with antiobesity medications receive those medications (Claridy et al., 2021). Because obesity is a chronic disease, she pointed out, it calls for chronic use of these drugs. Stanford identified as characteristics associated with greater odds of use of antiobesity medication female sex, White race, living in the southern region of the United States, and having private health insurance (Claridy et al., 2021). She added that, while metabolic and bariatric surgery is the best treatment for severe obesity, only 2 percent of individuals who meet the criteria for this surgery receive it.

The economic consequences of obesity are seen in health care spending, Stanford noted, as the economic impact of overweight and obesity rises as a percentage of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) (Okunogbe et al., 2022). She reported that, compared with the other high-income countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the United States is expected to have the highest average annual health expenditures per capita due to obesity during 2020–2025, representing 14 percent of the nation’s total health expenditures (Statista, 2019). In terms of impact on global GDP, Stanford shared data from 2014 indicating that the impact of obesity is only marginally behind that of smoking and armed violence/war/terrorism (Dobbs et al., 2014).

Stanford continued by observing that, in contrast with other countries (Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, and Spain), the United States lacks national obesity policies (Cooper, 2014). She mentioned the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act, first introduced in Congress in 2013, which is intended to cover antiobesity medications under Medicare Part D and behavioral treatments for obesity provided by specialists such as registered dietitian nutritionists. She noted, however, that this legislation has to date not been enacted.

Stanford ended her presentation with a recap of her key points. First, obesity is a multifactorial disorder, with disproportionate attention being paid to a subset of its causal and contributing factors. Second, BMI is problematic for ascertaining weight status, and work is under way on redefining how weight and weight status are defined and viewed. Third, weight stigma, often perpetuated by health care providers, harms the physiological and psychological health of patients who struggle with obesity. Fourth, pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery should be considered as an option for appropriate patients. Finally, the economic impacts of obesity are vast, yet U.S. policies addressing obesity are lacking.

PANEL AND AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Following the two presentations summarized above, Phelan facilitated a discussion and question-and-answer period with the speakers. He began by asking them to share their vision for an ideal obesity treatment paradigm

and followed with additional questions about addressing weight stigma and its consequences, focusing on weight loss versus weight-inclusive care, and intersectionality and obesity care.

Vision for an Ideal Obesity Treatment Paradigm

Stanford restated her view that obesity is undertreated and underappreciated as a chronic disease in the United States, where society places blame on deficits in individual responsibility and willpower based on the belief that people with obesity need to make better choices. She underscored that this perspective needs to shift because it does not value people as individuals and ignores the external, broader contributors to obesity. Her ideal treatment paradigm for patients with obesity would involve a tailored treatment plan, meaningful patient engagement and partnership with the health care team in making treatment decisions, and avoidance of a strong focus on BMI.

Stanford postulated that greater exposure to chronic stress and disruption of circadian rhythm, for example, helps explain why higher-income countries demonstrate more dysregulation concerning energy balance and storage relative to lower-income countries. No country offers a robust model for successfully addressing obesity, she submitted, suggesting that such a model would include efforts to educate physicians and other health care providers about treating obesity and a track record of treating people with obesity with dignity and respect.

Ibrahim agreed that physicians often do not treat obesity as a disease and tend to blame the patient. He affirmed that health care has a role in supporting weight management, but he also suggested that obesity is a more complex problem than health care alone can handle. Health care is designed to address acute health problems, he elaborated, whereas obesity involves many social dimensions that health care providers do not naturally address. Additional solutions beyond those in health care are therefore needed, he stated, to address the environmental and social factors that play a role in the development of obesity. Ibrahim reported that as health care systems have increasingly recognized that health happens beyond the walls of hospitals and health system settings, he has observed a growing emphasis on shifting care from the hospital to the community. Health care systems have begun to realize that they are responsible for the health of the community, he continued, not just that of individual patients. He urged health care providers to advocate for and participate in community solutions and to discuss such topics as places to be active during patient counseling opportunities.

Addressing Weight Stigma and Its Consequences

Stanford shared a poignant anecdote to illustrate strategies for addressing weight stigma on an interpersonal level. She recounted an opportunity to care for a particular patient, whom she had noticed—but not talked with—when

he was working as the conductor on the morning train she took to work. Each morning she saw him and wished she could have him as a patient, she recalled, since she noticed that his excess weight was a strain on his body as he moved about the train. She conveyed her surprise and delight when he walked into her office several years later accompanied by his mother, who began crying when she recognized that Stanford was treating her son with dignity and respect, an experience she had not had with prior physicians.

Stanford reported that while she was caring for this patient using a combination of treatment strategies, his weight decreased from 550 to 300 pounds. That ending weight would be regarded as a failure by doctors who assume that health correlates directly with BMI, she contended, but she observed that at 300 pounds, the patient was happy and no longer had the array of comorbidities and clinical risk factors that were present before treatment. She concluded the story by stressing the importance of trust and positive interpersonal relationships between health care providers and patients with obesity, stating that patients will be reluctant to interact with health care systems where they feel stigmatized instead of being treated with empathy.

Ibrahim elaborated on the pathways through which weight stigma exerts its effects. First, he said, it has a demoralizing effect on patients, whereby they become dispirited and unlikely to engage in positive health behaviors. Stigma also impacts the likelihood of patients’ engagement with the health care system, he continued, and the likelihood of their adherence to provider recommendations. In short, he summarized, stigma is a mechanism by which the health care system fails patients.

Ibrahim recounted experiencing stigma’s impact firsthand during his tenure as a primary care doctor in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system. He described studies of perceived discrimination by race, gender, and other characteristics that were linked with weight stigma, which led to significant disparities in health care access, outcomes, trust levels, and patient satisfaction with care within that system.

Focus on Weight Loss versus Weight-Inclusive Care

Stanford confirmed that she regularly balances practicing weight-inclusive care and focusing on weight status with her patients. She stated that her goal is to help patients attain their best health instead of insisting that they reach a particular number on the scale. Weight is just one of several metrics considered in focusing on health, she maintained, adding that a benefit of aiming for a patient’s happiest, healthiest weight is that it eliminates much of the shame and blame that people with excess weight often experience in health care settings.

Stanford observed that people with excess weight are often questioned by health care providers about whether they are following the advice they have

received about eating and activity behaviors. She shared another anecdote, about meeting one of her former patients in a grocery store. This person had a history of severe obesity, she said, and as they conversed in the checkout line, she quickly glanced at the contents of the patient’s grocery cart. The patient saw her looking and stated that she had followed all of Stanford’s advice, and Stanford confirmed that the patient’s cart was a perfect picture of what had been discussed during their clinic visits. At that moment, Stanford continued, she recognized a personal bias—that she had assumed the patient was not following all of her advice instead of taking any responsibility as the provider to play her role in supporting the patient’s health journey. The kind of doubt she had evidenced does not make patients want to keep working with their health care providers, Stanford maintained, because if they feel that their doctor does not trust them, how can they trust their doctor?

Ibrahim concurred that tension often exists between respecting a patient’s preferences and perspectives on weight—or several other health-related topics—and delivering evidence-based care and guidance. He shared the example of elective joint replacement, which he characterized as highly preference sensitive, meaning that national guidelines are not available for determining who should undergo the procedure. Patients’ choices are therefore a major factor in the selection of treatments, he stated, and their preferences are shaped by many factors and may not be fully or accurately informed. An easy answer to this conundrum does not exist, he admitted, suggesting that these kinds of scenarios represent classic doctor–patient communication challenges.

Intersectionality and Obesity Care

Ibrahim shared that it was common for him to treat patients with multiple intersecting stigmatized identities in his prior patient-facing roles. He confirmed that it was a challenge to navigate those encounters, knowing that a focus on one identity would fail to address the other realities that were likely intersecting with weight issues. Striking the right balance in acknowledging all of an individual’s identities is an important decision, he said, as is identifying where to intervene. Ibrahim suggested that integrated care models could help address such intersectionality, referencing a VA health system practice of colocating behavioral health and primary care clinics because mental health issues are highly prevalent in veteran communities.

Stanford agreed that prevalent weight bias and race bias augment the challenges of intersectionality for individuals from underrepresented backgrounds. She underscored her previous comments about treating people with dignity and respect, noting that failure to do so compounds the stigma that people with obesity already experience and increases the likelihood that they will avoid or delay seeking care.

This page intentionally left blank.