Exploring the Science on Measures of Body Composition, Body Fat Distribution, and Obesity: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2024)

Chapter: 2 Obesity: Definitions and Perspectives

2

Obesity: Definitions and Perspectives

The first session in April included three presentations that provided background and a time line for body mass index (BMI) as a measure of adiposity and health and its effect on public health and clinical use. S. Bryn Austin, professor of social and behavioral sciences at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, scientist in the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, founding director of the Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders: A Public Health Incubator, and planning committee member, moderated and shared opening remarks. Austin explained that the planning committee sought presenters representing a wide range of perspectives and experiences to share familiar and novel research and viewpoints, consider, and invigorate a dynamic discussion.

CULTURAL APPROACHES TO OBESITY, BMI, AND NUTRITION

Edward (Ted) Fischer, cultural anthropologist, Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Anthropology, Management, and Health Policy at Vanderbilt University, and director of the Cultural Contexts of Health and Well-Being Initiative, kicked off the first session by stating that despite spending hundreds of billions of dollars on public health campaigns, clinical interventions, drug development, and other approaches, the rates of obesity in the United States continue to rise globally and nationally. While there is emerging science to better understand the underlying physiological processes to treat it and improve health, Fischer stated that it is necessary to also take into

account structural racism and the cultural, colonial, and commercial factors that interact with metabolic processes to produce certain outcomes. He elaborated that the cultural lens in biology, medicine, politics, environment, culture, and economics and colonial patterns of exclusion underwrote institutions and frameworks.

Fischer shared that his research team prioritizes people living in larger bodies to understand their clinical care experiences, particularly when they learn about their BMI and diagnosis of obesity. He explained that the results of their research yielded three areas where cultural insights could mitigate implicit bias and improve health outcomes for people living in larger bodies if they were integrated into health policy and clinical care.

The first cultural insight is that “health is more than weight.” Body size ideals are social constructs and different countries and cultures perceive larger bodies differently. He explained that modern body ideals originated from Western enlightenment (1685–1815) and colonialism in a racialized and gendered way. The astronomer and statistician Adolphe Quetelet developed BMI using the height and weight of European adult men (Eknoyan, 2008; Strings, 2019), leading to the European male body serving as the comparison group for all men and women.

Fischer continued by stating that people were ranked based on their body types; individuals of African, Asian, and Native American descent ranked lower than people of European descent. The results justified the colonial narrative and moralized body size with the body ideal of thin European men associated with self-discipline. Accordingly, Fischer added, women living in large bodies with dark skin were considered lazy and unwilling to forego short-term pleasure for long-term gain. Though entirely biased, the persistence of the moral prescription of body size in the United States represents a cultural fact, he said.

A cultural fact motivates behavior and is impressionable, based on tradition, experience, and popular sentiment, and not necessarily supported by science. It is as material and motivating as a scientific fact based on empirical data, measurement, and logic.

Fischer continued that scientific evidence does not support the idea, and cultural fact, that weight is an unequivocal indicator of metabolic health regardless of racial and ethnic background. He shared research by Venkat Narayan that suggests an alternative pathway to type 2 diabetes in South Asians in Chennai, India, which presents at a lower BMI than in Western populations (Venkat Narayan et al., 2021, 2022). By contrast, Fischer said, 85 percent of U.S. individuals with type 2 diabetes also have obesity, yet some U.S. residents with a normal BMI are metabolically unhealthy.

Fischer added that the energy balance model that explains weight gain as the result of more calories consumed than expended reinforces the cultural fact that people living in larger bodies are lazy and lack willpower.

He stated that although science has emerged to indicate complex and multilayered systems that differentiate human genetics, the gut microbiome, and the foods consumed, clinicians and policy makers have reinforced the moralization of body size, which has led to unsuccessful treatment and impractical health care policy.

The second cultural insight is “diet is more than individual choice.” The U.S. obesogenic environment is shaped by global, agricultural, and industrial systems that foster market access and restrict consumer choice and consumption of processed and ultraprocessed foods. It therefore bolsters the cultural fact that people with obesity are overindulgent.

Fischer posed a thought experiment to illustrate the impact of cultural facts on the environment.

Imagine the heat was turned “off” while away from home. Under normal circumstances, the house temperature is 75 degrees Fahrenheit, so upon return, the house is notably cold. To address this issue, the thermostat could be adjusted to increase the house temperature.

In his research, about 40 percent of people surveyed would turn the thermostat to 85 degrees or higher to return their house to 75 degrees. The remaining 60 percent of people would turn the thermostat to 75. The chosen strategy represents a cultural fact and demonstrates that people hold different beliefs and understandings of how a thermostat operates: Forty percent believed that it is a valve, meaning that the higher the thermostat temperature, the more heat is released. The other 60 percent understood that it responds and adjusts to the external temperature based on the temperature setting. Fischer reiterated that cultural facts influence behavior, so policies that aim to change dietary behaviors would be most effective if scientific and cultural facts were incorporated.

The last cultural insight is that “food is more than nutrition.” From a scientific standpoint, food is the medium for nutrients to enter the body. From a cultural standpoint, the value of food relates to social relationships, love, and identity, including religious affiliation. Fischer acknowledged that the science of nutrition examines the metabolic impact of food consumption and identifies dietary components or substances that may impact metabolic processes to improve health. However, most people organize their diet based on social characteristics rather than the science of micronutrients or calories.

For example, Fischer offered, in Mayan communities in Guatemala where malnutrition is a predominant issue, mothers living in poverty frequently give their young children soda. For them, soda is affordable, indulgent, and a way to express love and care. Fischer compared the mothers’ behavior to faith commitments to keep halal or kosher or consumer affinity for organic or locally produced foods.

Fischer stressed that public health campaigns that do not incorporate cultural context or that shame and blame and do not highlight the motivating factors or reasons for dietary habits will be ineffective. Culture and cultural context are quintessential to change behavior. Food and beverage companies understand their importance and influence and use them for marketing.

BMI CATEGORIES, DRUG COMPANIES, AND THE DRIVE FOR REIMBURSEMENT

Katherine Flegal, a consulting professor at Stanford University and former senior scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics, discussed the evolution of BMI categories and health care coverage of obesity. Many U.S. adults with BMI ≥30 kg/m2, and many adults with BMI <25 kg/m2, especially women, report having tried to lose weight in the past year (Martin et al., 2018).

According to a 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, prior to the late twentieth century, overweight and obesity were not considered a population-wide health risk (IOM, 2012). Flegal explained that weight loss was largely seen as a cosmetic issue, not as a health issue. She noted that there were some weight-loss drugs though most were relatively ineffective and some even caused health problems and were withdrawn from the market. As a result, Flegal said, health insurance companies did not cover weight-loss treatments, and they were not considered a medical deduction.

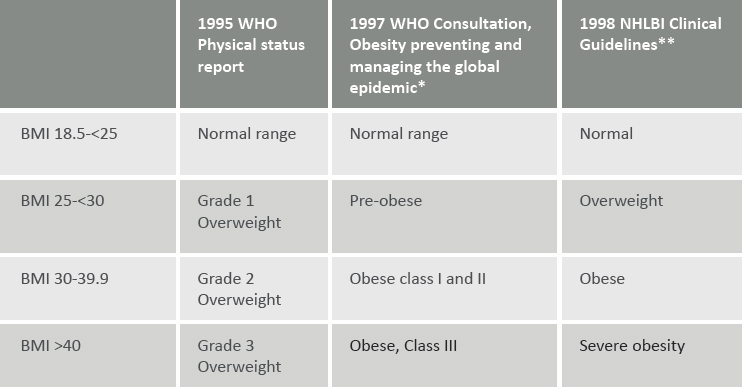

A 1995 World Health Organization (WHO) report outlined anthropometric measurements for normal weight, underweight, and overweight in pregnant women, infants, children, and adults and included three grades of overweight defined by BMI cutoffs of 25, 30, and 40 kg/m2 (WHO, 1995), describing these cutoffs as “largely arbitrary.” The report mentioned increased mortality with a BMI of 30 or greater but did not provide a reference for the statement. Notably, there was no definition of obesity with respect to body fat or BMI level.

Flegal read that a Roche company spokesman disclosed that part of the challenge in selling such weight loss drugs was to medicalize weight management for physicians. Two years after the release of the 1995 WHO report, the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF), with funding of over a million British pounds from the pharmaceutical industry (Peretti, 2013), persuaded WHO to hold a new consultation on obesity in 1997, said Flegal. Flegal continued, the IOTF drafted the report for the 1997 consultation and because the publication of the final report of the 1997 consultation was delayed until 2000, the IOTF paid for the publication of a 1998 interim version of the report and additionally paid for the distribution of the interim

version to health ministers of all UN countries and to others who requested it (James, 2008). In 1995, Flegal continued, four scientists from IOTF also served on a committee at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) that established new guidelines for overweight and obesity. Flegal said that the 1997 WHO consultation report used the same BMI categories as the 1995 WHO report but changed the nomenclature from “overweight” to “obesity” for BMI levels of 30 kg/m2 or above (see Figure 2-1).

Thereafter, Flegal said, national reports on BMI highlighted the prevalence of obesity in the United States based on the updated NHLBI cutoffs. However, clinicians were not reimbursed for treatment of obesity since it was not listed as an illness in the U.S. Medicare Coverage Issues Manual, which directs reimbursement for clinical services, she said. Flegal explained that an IOTF member who had joined CDC organized and chaired a CDC meeting about reimbursement of health care providers for obesity treatment, leading to the removal of language that “obesity is not an illness” in the Medicare Coverage Issues Manual.

Flegal noted that we have a definition of normal weight in terms of BMI, yet pointed out that at least half of the population in many countries, including European countries, are over the normal weight based on their BMI. Perhaps, she said, the definition of what is normal is not working.

Flegal said that Rubino et al. (2023) pointed out that the attribution of disease status to obesity defined exclusively by a BMI threshold is an

NOTES: *The classification is described as “in agreement” with the 1995 report; **The source of the classification is given as the 1998 interim report. BMI = body mass index (BMI units are kg/m2).

SOURCE: Presented by Katherine Flegal, April 4, 2023. Reprinted with permission.

intrinsically flawed concept and does not measure existing illness. As also pointed out by Rubino et al., Flegal continued, a blanket definition of obesity as a disease involves a significant proportion of the population worldwide. This definition could render large numbers of people suddenly eligible for claims of disability or expensive treatments. Such claims would effectively make obesity a financially and socially intractable issue (Rubino et al., 2023). Recent peer-reviewed research provides a shift in thinking from using BMI as a predictor of future disease or mortality to a clinical definition of obesity that measures existing illness (Bosy-Westphal and Müller, 2021; Rubino et al., 2023).

CLINICAL CONTEXT: HOW CAN WE MEASURE A DISEASE TO TRACK ITS IMPROVEMENT?

Donna Ryan, professor emerita at Pennington Biomedical and consulting advisor to companies for obesity management, was the third presenter. As a clinician, Ryan focuses on identifying a measure that can define obesity as a disease and tracking its progress with clinical treatment. She provides continuing medical education to clinicians on obesity diagnosis and treatment and consults with companies on lifestyle interventions, medications, and medical devices to treat obesity.

Ryan agreed with Flegal that obesity is a disease with an etiology and pathogenesis. Before 2004, she continued, it was not listed as a disease by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and Health Care Financing Administration for reimbursement claim submissions for professional services to treat it. Ryan asserted that the tipping point for it to be considered a disease was the 2013 American Medical Association (AMA) resolution, even though several professional society white papers, position statements, and the 1998 NHLBI obesity guidelines already deemed it so (Kyle et al., 2016).

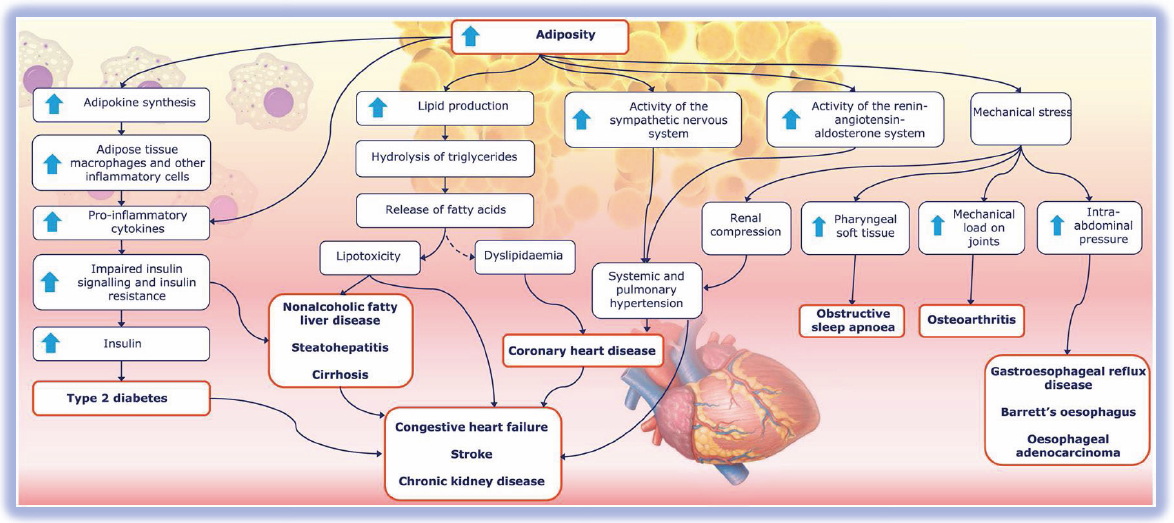

Ryan acknowledged the debate on obesity as a disease in the medical community and provided an overview of the etiology and pathogenesis for this conceptualization. Ryan introduced the Soggy Bathroom Carpet Model of Over-Nutrition-Related Metabolic Disease (O’Rahilly, 2021), which posits that given a continuous positive energy balance that compromises the body’s ability to store healthy fat in the adipose tissue depots (e.g., hips; thighs), ectopic and abnormal fat stores (in and around organs) increase, leading to metabolic disease (Blüher, 2020). In the bathtub metaphor, when a person consumes more energy than is expended in physical activity, their consumption acts as the faucet, their energy expenditure acts as the drain and the extra energy is stored as fat in the bathtub. When the adipose tissue stores exceed the capacity of the bathtub, the extra energy and fat overflow to become a soggy bathroom carpet, representing dysmetabolic disease (e.g., type 2 diabetes).

Ryan explained that where the body stores fat (healthy fat storage in the hips and thighs or ectopic, unhealthy fat storage in and around organs) is determined by factors such as age, medications that instigate lipodystrophy, and hormone fluctuations in menopause. Unhealthy ectopic and visceral fat stores behave differently from healthy subcutaneous fat. Microscopically, the ectopic and visceral fat tissue exhibits enlarged cells and dying helmet cells infiltrated by macrophages that produce adipokines, leading to thrombosis and inflammation.

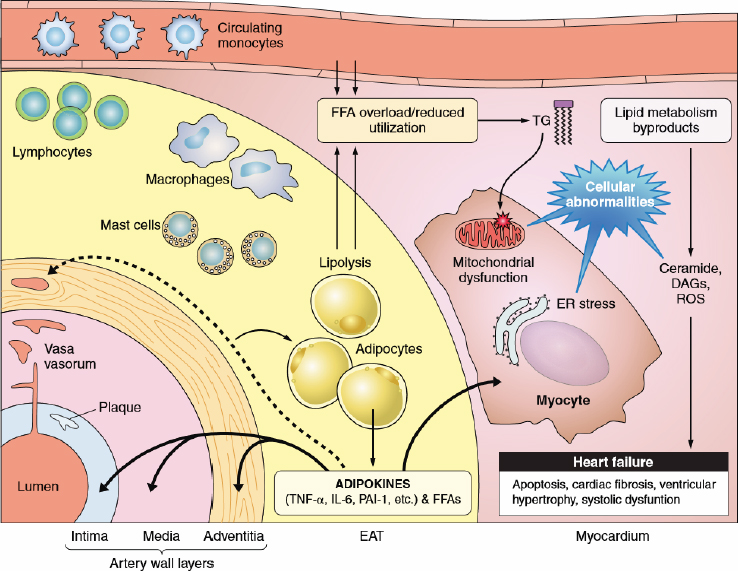

According to Ryan, the true definition of obesity is “excess abnormal body fat that leads to poor health outcomes.” The fat’s location determines the pathogenesis for complications (see Figure 2-2).

Ryan described the anatomy of epicardial adipose tissue, which is located under the pericardium and epicardium, adjacent to the myocardium and traversed by the coronary arteries. It can promote damage to the

NOTE: DAG =-diacylglycerols; ROS = reactive oxygen species; EAT = epicardial adipose tissue; ER = endoplasmic reticulum; FFA = free fatty acids.

SOURCES: Presented by Donna Ryan, April 4, 2023. Cherian et al. (2012). Reprinted with permission.

myocardium and atherogenesis in the coronary arteries by direct exposure to adverse cytokines.

Ryan added that the mechanical burden of excess abnormal fat can also lead to disease. For example, she said, greater visceral adiposity causes intra-abdominal pressure that increases the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Another example is that excess adipose tissue near the neck can constrict the airway system, leading to a mechanical burden and sleep apnea (see Figure 2-3).

Fortunately, Ryan continued, the body preferentially removes ectopic and visceral fat tissue during weight loss, which immediately benefits health. The physiology of weight loss, she reiterated, is that different tissues respond differently to different degrees of weight loss. By removing abnormal body fat, a person can reduce their risk for metabolic disease. She specified that a proportional weight loss of 5, 10, and 15 percent yields health benefits but not necessarily a BMI in a “normal or healthy range” (≤25 kg/m2). To illustrate this point, Ryan noted that most participants of the Diabetes Prevention Program who demonstrated an impaired glucose tolerance and lost 5–10 percent of their body weight prevented their progression to type 2 diabetes (Hamman et al., 2006), despite still being classified as having overweight or obesity by BMI.

Ryan acknowledged valid criticisms of BMI cutoffs as a screening tool. In the clinic, some patients with a BMI >30 kg/m2 are metabolically healthy, and others with a healthy or normal BMI (<25 kg/m2) have excess abnormal body fat and metabolic complications. Clinical judgment, she affirmed, is essential to diagnose obesity based on evidence from measuring excess abnormal body fat by waist circumference and assessing its cardiometabolic risk factors and symptoms.

Ryan pointed out that most clinicians recognize that BMI does not assess health, although it is important because it is automated in electronic health records (EHRs), is included as a diagnostic code for overweight and obesity (E66) in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), and directs insurance coverage. However, she said, only 50 percent of patients who meet the BMI criteria are diagnosed with obesity on the medical record, and only 21 percent of Medicare claims include a diagnosis of obesity, because clinicians are not reimbursed for a comprehensive spectrum of treatments associated with the diagnosis.

Ryan noted that alternatives to BMI do have limitations. The clinical setting has no reliable measure for percent of lean and fat mass. The gold standard to measure fat mass, lean mass, and location is dual X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), although it is unfeasible for regular widespread use because of the radiation exposure. Ryan mentioned other tools, such as bioimpedance analysis, which is easy to use but inaccurate, and air displacement plethysmography (i.e., Bod Pod), which measures body fat volume but

SOURCES: Presented by Donna Ryan, April 4, 2023. Wilding and Jacob (2021). Reprinted with permission.

is cumbersome, expensive, and unable to specify fat distribution. She also mentioned digital anthropometry through phone applications (e.g., Me3601), which is intuitive for untrained individuals to accurately determine their body fat percentage by measuring bicep, thigh, stomach, and calf circumferences, but it requires validation in clinical research. Ryan ended by underscoring the need for an additional tool to complement BMI to clinically diagnose obesity and allow clinicians to track their patient’s treatment and progress.

PANEL AND AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Following the panel presentations, Austin moderated a discussion. Fischer, Flegal, and Ryan addressed questions from workshop participants about educating students on the nuances of the energy balance model; alternatives to BMI to surveil population health; debates about the utility of BMI in the clinical setting; the origin of the “obesity epidemic”; and the intersections of racial and gender stigmas with weight stigma.

Educating Medical and Allied Health Students on the Nuances of the Energy Balance Model

Austin referred to Fischer’s presentation and thesis on the racist and colonialist narrative of weight stigma and its support for the energy balance myth. Yet, she contended, the energy balance model persists in medical schools and schools for allied health care professionals. Austin asked Fischer to comment on how universities can educate students on the flaws of that model.

Fischer emphasized the importance of uncovering students’ and instructors’ implicit biases that reinforce scientific or pseudoscientific models. He proposed interrogating the conceptual framework for obesity to reduce bias and incorporate anthropology into curriculum, including lived experiences and examples from other countries and cultures. For example, he added, the Japanese government redefined obesity as a metabolic syndrome through additional measures for a composite to examine disease pathology, beyond body weight.

Alternative Measures to Surveil Obesity and Public Health

Austin reminded the audience of Flegal’s presentation on the history and role of commercial actors in the WHO IOTF consultation report, the obesity epidemic, and the concept of obesity as a disease. Given this history, Austin asked Flegal how we can reconcile BMI’s use as a public health surveillance tool.

___________________

1 https://www.methreesixty.com/body-fat-calculator (accessed September 22, 2023).

Flegal responded that public health reports must clearly define their relevance and importance for public health. She recounted publications on the prevalence of obesity measured by BMI that highlighted it as a significant public health problem in the United States. According to Flegal, these reports were somewhat misleading because they were saying people had a disease when there was no reason to think that these people necessarily had a disease. The articles were well received by pharmaceutical companies and public health because the high prevalence of obesity showing that obesity is an epidemic gave them something to work with. However, Flegal said, these reports could be contributing to weight stigma and harm.

Function of BMI in Clinical Practice

Austin reminded participants of Ryan’s presentation on the complexity of adipose tissue, the challenges to accurately measure it, and the recognition that BMI as an embedded measure in EHRs will persist in monitoring health. She asked Ryan, “How can clinicians avoid using BMI?”

Ryan emphasized that BMI is a screening tool and obesity is a clinical diagnosis. Furthermore, she added, it is in the ICD codes for diabetes and fatty liver disease, and patients with these diagnoses benefit from weight loss. She reiterated that the objective of therapeutic weight loss should not be to achieve some BMI cutoff. That may not be needed for health benefits. Reaching certain targets for proportional weight loss (e.g., 5, 10, or 15 percent) can produce health benefits in persons who still meet BMI criteria for overweight or obesity.

Origin of Obesity as an Epidemic

An audience member asked Flegal whether catastrophizing obesity as an epidemic originated from the business or public health sector. Flegal stated that the origin of the obesity epidemic stemmed from both sectors, as well as cultural and economic factors. For example, there is a notable cultural difference in attitude about weight between men and women. Further, people are heavily invested in these issues and put them forward.

The Intersection of Racial Stigma, Gender Stigma, and Weight Stigma

The last question from the audience asked Fischer whether the literature distinguishes between racial and gender stigma regarding weight stigma and whether one is more strongly predictive of weight stigma. Fischer admitted he had not considered if one factor was more influential than the other but said that it was a critical future research question.

This page intentionally left blank.