Exploring the Science on Measures of Body Composition, Body Fat Distribution, and Obesity: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2024)

Chapter: 7 Innovations in Communicating About Body Weight in the Clinic and Beyond

7

Innovations in Communicating About Body Weight in the Clinic and Beyond

The second session, moderated by Craig Hales, was dedicated to innovations for providers to communicate with patients about body weight in the clinical setting and beyond. The first presentation focused on educating future clinicians about weight bias and stigma, followed by a presentation on speaking with patients about body positivity in a culture of obesity treatment and weight loss. Afterward, Hales facilitated an audience and panel discussion.

EDUCATING FUTURE CLINICIANS ABOUT WEIGHT BIAS AND STIGMA

Kofi Essel is a board-certified community pediatrician at Children’s National Hospital, assistant professor of pediatrics and director of the School of Medicine and Health Sciences Culinary Medicine Program, Community/Urban Health Scholarly Concentration, and Clinical Public Health Summit on Obesity at George Washington University (GWU). Essel’s presentation was on obesity stigma, its effects on medical and allied health care students, and strategies to reduce weight bias, stigma, and shame among students in universities.

Essel began by noting that faculty must recognize that medical students do not come into their training as blank slates and that it is necessary to be aware that their past lived experiences greatly influence their polarized perspectives on patients with obesity. Adding discussion of obesity stigma into a formal curriculum is critical, because if not, students absorb a hidden curriculum of cynicism seen in images and heard in comments from professors and providers that are engrained in clinical training.

Essel called out medical education, clinicians, and health care providers as all having played a role in amplifying weight bias and stigma. He pointed to Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, which spearheaded the social marketing campaign “Stop Sugarcoating It, Georgia,” with images of children who have overweight and obesity on billboards. Although the campaign intended to bring awareness to the rising rates of obesity in children, it perpetuated weight stigma. According to Essel, campaigns such as this strategically and intentionally dehumanize, belittle, humiliate, and stigmatize people with overweight and obesity.

Essel highlighted research that has shown physicians describe patients who have overweight or obesity as noncompliant, lacking self-control, less healthy, less intelligent, and having lower self-esteem (Huizinga et al., 2010; Puhl and Heuer, 2009). When medical students learn of these reactions, they are shocked and assume it is not relevant to them because they will be different. Essel highlighted this as the opportune moment to expose students to their own biases and teach strategies to provide person-centered care and communicate about overweight and obesity with patients.

Essel and a team of faculty designed the Public Health Summit to teach medical students about how to engage obesity with tools of health equity and empathy. He described the almost 30 hours of curriculum to be a rare opportunity to educate them about the complexity of obesity and stigma and discuss these topics with peers and instructors. Shiriki Kumanyika’s Framework for Increasing Equity Impact in Obesity Prevention (Kumanyika, 2017, 2019) guides the summit; medical students learn about the harmful effects of obesity stigma from people with lived experience and receive a population health perspective centering on health equity by working with local community-based organizations, state agencies, and numerous key stakeholders.

Essel noted that the summit was in its 8th year and has provided him and his colleagues an opportunity to create a formula and curriculum to train medical students on weight bias and stigma. Activities include the Harvard Implicit Association Test (IAT) on weight and a reflection exercise designed by Tom Sherman at Georgetown University on the students’ experiences engaging patients with obesity. He emphasized the importance of anonymous responses to the reflection exercise, so that students are honest about their experiences without fear of judgment or retaliation.

Essel shared that most students have an implicit bias toward people living with large bodies. Unpublished data from the summit from 2018 to 2023 shows that over three-quarters of attendees preferred thinner body frames; 10 percent preferred larger body frames, and about 15 percent did not have a preference. Nationally, research shows the same trends of implicit bias against people with overweight and obesity among medical students (Miller et al., 2013).

When students are confronted with their bias, Essel continued, many are in denial, and skeptical of the IAT test and its results, and confused about the implications of the findings:

I am skeptical of this [my] result. I found the test instructions rather confusing. Therefore, I do not necessarily believe that the IAT-weight is the best measure of a person’s attitudes toward overweight people.

Essel highlighted other student responses, including the uncoupling of implicit versus explicit bias, meaning a student believes they have an innate ability to separate what they think about patients internally (conscious or subconscious) from how they treat patients. Students also reveal overt bias in response to their implicit bias:

I do not think someone being obese means that they are bad people or less deserving of health care or other basic human rights. I do think it means that they do not really care about their health, or they are just less informed about health issues related to obesity, which does make me judge them a bit on that front. I think a little bit of stigma against obesity honestly would not be the worst thing. If anything, it would serve as an incentive for people to try and lose weight.

Essel described these perspectives as remnants from their formative years that can become integrated into their knowledge as medical students, amplified, and affect how they treat patients and their families later on when they become physicians.

Last, Essel said, some students react with rugged individualism (they were overweight and have lost weight). They view their weight loss as having gained control of their life and are confident and often condescending toward others, indicating that if they could lose weight, anyone can lose weight.

Essel offered 10 lessons learned from the summit that are relevant for all health care professionals (Alberga et al., 2016; Haqq et al., 2021; Kirk et al., 2020; MacInnis et al., 2020; Rubino et al., 2020). First, providers must increase their awareness of personal and collegial bias against obesity with tools such as the IAT-weight. Second, staff and colleagues must be trained to counteract bias against obesity using experiential learning and narratives from patients with obesity through their health care system or organizations such as the Obesity Action Coalition. Third, obesity must be recognized and taught as a complex, multisystem disease and not just a number on the scale. Essel agreed with other presenters that it is not always easily managed with lifestyle changes alone. Fourth, health care professionals must respect patient autonomy. Some do not want to lose weight or discuss weight at

every visit. He said that the new craze around the “Please don’t weigh me” cards is a response to health care not providing a safe space for patients and families, forcing them to take their dignity and humanity in their own hands. Sixth, he indicated that health should be taught as the primary goal, not cosmetic thinness or Western beauty standards. Weight is a contributing factor for many conditions and chronic diseases, but the role of physicians and allied health care professionals, he emphasized, is to support families in improving health, treat patients with dignity, and recognize their humanity. This sometimes will require strategies to directly support weight loss, but never should be viewed external to health. Seventh, an equitable health care environment must be created to accommodate and serve a range of patients with equipment that meet the needs of people with different body sizes. Eighth and ninth, he recommended that clinicians use people-first language and nonstigmatizing images of people with obesity. Tenth, he urged students and colleagues to take the pledge of the international joint statement to eliminate weight stigma (Rubino et al., 2020).

NAVIGATING DISCUSSIONS GRACEFULLY IN A BODY POSITIVITY VERSUS OBESITY TREATMENT WORLD

Robyn Pashby, a clinical health psychologist who specializes in the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional factors of health behavior change, was the second presenter focusing on body positivity and obesity treatment as two divergent yet overlapping styles of understanding.

As Sarah Tyrrell has said, “I was raised to believe fat was the worst thing a girl could be.” Today’s environment has a range of perspectives on weight, body image, and language. For example, some people practice body positivity, others subscribe to the concept of Health at Every Size,1 and still others feel shame about their weight and self-advocate with the “don’t weigh me” card that Essel mentioned. Providers must navigate these fundamentally different viewpoints when discussing health and obesity, Pashby said.

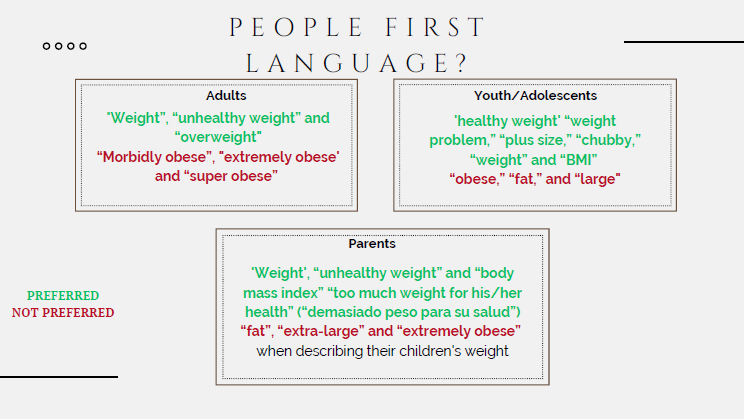

Pashby suggested that people may understand obesity without understanding how to talk about it. Professional organizations have made countless efforts to help define obesity but rarely offered an opportunity to understand ways to talk to people about it. One example was that individuals in the fields of science and medicine advocate for providers to use people-first language (e.g., “person with obesity”) because a person is not their disease (see Figure 7-1). However, research shows that patients do not necessarily prefer this, favoring words such as “weight,” “healthy weight,” and “chubby” (Brown and Flint, 2021; Puhl, 2020; Puhl et al.,

___________________

1 https://asdah.org/health-at-every-size-haes-approach (accessed September 15, 2023).

SOURCES: Presented by Robyn Pashby, June 26, 2023 (data from Brown and Flint, 2021; Puhl, 2020; Puhl et al., 2022). Reprinted with permission.

2022). She emphasized that this example illustrates the need for clinicians and health care providers to continue listening and learning from patients.

Pashby turned to offering four concrete strategies to help bridge the gap between body positivity and obesity treatment in clinical practice and elsewhere. First, clinicians must understand the gap between body positivity and obesity treatment. According to Pashby, the conflict stems from the erroneous belief that body positivity promotes obesity. Pashby assured the audience that it is a movement for acceptance of all bodies regardless of their size, shape, skin tone, gender, physical abilities; it does not promote obesity.

Pashby reminded the audience that the U.S. weight-loss culture equates weight loss with aesthetics. For example, a recent social media advertisement promoted ways to “dress slim.” Weight-loss culture is not about health, and a person experiencing internalized weight bias will still do so after they lose weight. Pashby affirmed that weight is not the issue with weight bias.

Second, Pashby challenged the audience to reconsider their assumptions about weight and weight loss and reflect on how it impacts their perspective of people with obesity. She suggested clinicians consider whether every patient wants to be thinner and whether body size is an indicator of nutrition knowledge and the effort to eat healthy and exercise.

The third strategy was for clinicians and providers to make “better” assumptions. Patients may or may not want to lose weight or be body

positive. A person who is overweight may be very knowledgeable about taking care of themself and have put forth sustained and exhausting effort for their health. She encouraged providers to assume that patients can make health care decisions even if these are not aligned with the provider’s clinical judgment and that their patients may feel alone, judged, and shamed, blame themselves, and have a strong need to please their provider. Consider the ramifications of a patient agreeing to lose 10 pounds between doctor’s visits who does not or cannot achieve that, she said.

The fourth strategy is to learn and adopt trauma-informed care (Green et al., 2015). Assume a patient has experienced a traumatic stressor—not just adverse childhood events but also the traumatic stress of living in a larger body. She underlined that trauma-informed care is not trauma treatment. Rather, it accounts for the possibility that every patient may have a history of trauma exposure and forces clinicians to consider safety and transparency in the patient–provider relationship based on trustworthiness, collaboration, and cultural sensitivity.

Next, Pashby outlined steps providers can take to communicate and engage patients about a health concern for which they feel shame (e.g., bariatric surgery). She suggested that clinicians consider the context of an appointment and talk to patients about their thoughts and feelings and not just the outcomes. Providers need to consider the barriers to lifestyle changes and the tone of their voice, ask permission to speak about a given topic, and use trauma-informed care.

Pashby then presented three scenarios and example scripts for clinicians to use when communicating with patients about their health concerns.

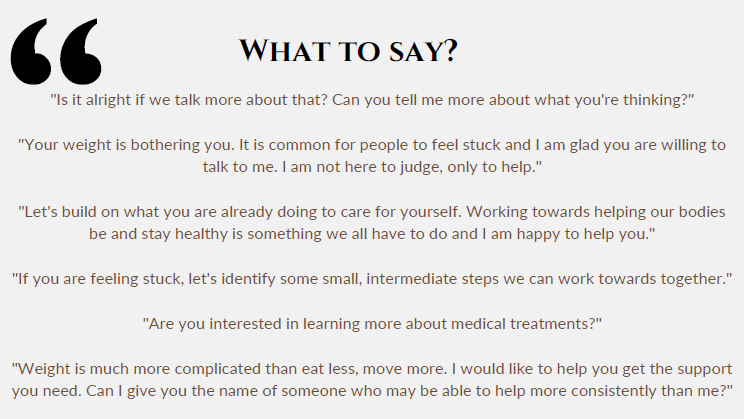

In the first scenario (see Figure 7-2), Pashby described a patient who tells their clinician, “I want to lose 100 pounds.” The starting point for responding is to consider their perspective. She suggested discussing their thoughts and feelings because these strongly impact behavior. Is the patient trying to beat their clinician to the punch? Do they assume the clinician will comment on their weight? Are they ashamed, frustrated, or exhausted? Are they worried about their health? What is the context of the appointment? If the patient is there for strep throat, how would they react to a pamphlet about bariatric surgery? She encouraged clinicians to imagine responding to the patient with “Let’s build on what you are already doing to care for yourself.”

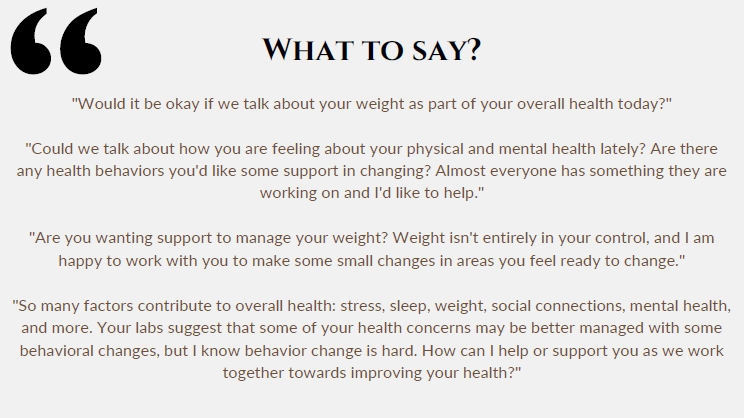

Pashby presented a second scenario at an annual physical exam (see Figure 7-3). The clinician thinks the patient’s health may be impacted by their weight. She recommended that they consider the patient’s perspective and focus on their thoughts and feelings, not the outcome. Is the patient intentionally avoiding a discussion about their weight? Do they feel hopeless and stuck, or are they practicing body positivity or Health at Every Size? Are they in an active or recovery phase of an eating disorder? Imagine

SOURCE: Presented by Robyn Pashby, June 26, 2023. Reprinted with permission.

SOURCE: Presented by Robyn Pashby, June 26, 2023. Reprinted with permission.

responding to the patient with “Would it be okay if we talk about your weight as part of your overall health today?”

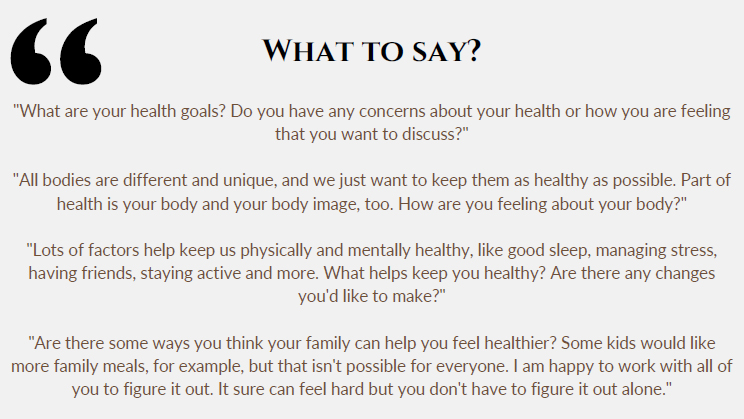

The third scenario Pashby offered was at a pediatric appointment with parents about their child’s weight (see Figure 7-4), which is complicated. Begin the conversation from a place of openness, safety, and transparency. She appealed for clinicians to consider changes for the family when thinking about changes for the child and the context of the appointment. Is the visit for an ear infection? How will the parents respond if the clinician introduces pharmacotherapy for obesity treatment? Imagine responding to the parents with “Lots of factors help keep us physically and mentally healthy, like good sleep, managing stress, and having friends. What helps keep you healthy? Are there any changes you’d like to make?”

Pashby concluded that to close the gap between the two camps (body positivity and obesity treatment), clinicians must consider how patients feel mentally. How a provider communicates with a patient directly affects how they think and feel; those affect their actions, which influence their behavior, such as physical activity, diet, and sleep. Of course, she said, also follow through with medical treatment, using medications as prescribed, attending medical appointments, and therapy. As one of her patients said, “My ability to do the things that I know are good for my health is tied directly to how I feel mentally.”

SOURCE: Presented by Robyn Pashby, June 26, 2023. Reprinted with permission.

PANEL AND AUDIENCE DISCUSION

Hales led a moderated discussion. The audience asked Essel and Pashby questions about increasing awareness of personal weight bias and stigma among medical faculty, the value of eating less and moving more in obesity treatment, social determinants of health (SDOH), awareness of weight bias and stigma among medical students, and strategies to discuss routine weighing in the clinical setting.

Working with Colleagues to Increase Their Awareness of Weight Bias and Stigma

The first audience question was for Essel, about how he engages and works with colleagues and other faculty who demonstrate weight bias and stigma. After all, the participant commented, students learn from their behavior modeling. Essel responded that the professional dynamic is universal. The team at Children’s National Hospital completed chart reviews and found that some language was not up to par. He recalled one example of “buffalo hump” instead of “dorsocervical pad of fat.” Or the frequent use of the term “morbid obesity” instead of “severe obesity.” The first step, he said, is to think about how to transform the thinking process, posture, and language clinicians use when writing and discussing. The goal is to create a greater awareness of weight bias and stigma among not only students but practicing clinicians. Essel advocated giving providers and medical students the opportunity to hear from families with children who have been affected by the lack of empathy and overt and passive stigma expressed in clinical spaces because it is very effective at raising awareness.

Eat Less and Move More as a Treatment Strategy

The next question from the audience was for Pashby about messaging to eat less and move more in obesity treatment. Does it have a role for patients with obesity? How does it fit into your treatment strategy? Pashby responded that patients have heard this message for decades and internalized it. Why would a clinician reiterate it? Pashby recommended emphasizing activities that the patient loves. That perspective causes a shift from focusing on their body size as unacceptable toward identifying activities that they enjoy.

SDOH and Medical Students

Essel received the next question from the audience about how SDOH influence health care. How does an increased awareness of these affect medical students’ perspectives? Essel shared that if faculty teach medical

students about SDOH, population health, and public health, then they will have greater awareness and understanding of systems that can lead to increased weight gain and other chronic conditions. However, he continued, that hyper-focusing on SDOH does help students get a better understanding and build empathy, but they can also begin to develop new narratives that indicate obesity is only “acceptable” for those experiencing poverty or who are marginalized. SDOH are critical to understand, but he emphasized the complex models and systems that influence obesity are just as critical. He summarized that obesity risk is more than social risk due to income inequities.

Shifting Away from Routine Weighing in the Clinic: Conversations with Patients

The last question went to Pashby. How can clinicians respond to a patient saying they do not want to be weighed during the office visit? Pashby answered that they should determine if weighing is necessary; it is not at every clinic visit, and they could offer to put a note in the file saying this person prefers not to be weighed. They can also ask about a history of an eating disorder. The likelihood that a person living in a large body has experienced trauma is high. Think about the location of the scale. Is it private or in a high-traffic area? Is weight recorded in the chart or said aloud? Offer to let the patient stand with their back to the scale. Explain why recording their weight is necessary at the visit. Alternatively, ask about a weight on file or any significant weight change since their last visit.