Exploring the Science on Measures of Body Composition, Body Fat Distribution, and Obesity: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2024)

Chapter: 8 Ethics and Trust in Communicating About the Intersection of Body Weight and Health

8

Ethics and Trust in Communicating About the Intersection of Body Weight and Health

The third sessions, moderated by Bryn Austin, featured three presentations highlighting ethics and trust when communicating about body weight and health, policies to mitigate poverty in the context of food and health, and cultivating trust in the patient–provider relationship. A panel and audience discussion followed.

WEIGHT-RELATED STIGMA AND HEALTH DISPARITIES

The first presentation was given by Tracy Richmond, director of the Boston Children’s Hospital Eating Disorders Outpatient Program and the STEP wellness program for youth with an elevated body mass index (BMI), on weight-related stigma and health disparities. She noted the tension of her roles in the two fields of eating disorders and childhood obesity. To illustrate, she used body acceptance as an example. The field of disordered eating believes that everyone should accept all body sizes and shapes. The field of childhood obesity believes that everyone above a certain number or BMI threshold should lose weight.

Richmond noted that the 2023 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guideline for childhood obesity has received considerable media attention on its recommended interventions, such as weight-loss medications or surgery (Hampl et al., 2023). Less attention has been given to the guidance for patient–provider communication: that clinicians communicate BMI to the patient and their family because it provides rationale for a comprehensive evaluation and treatment of obesity and related comorbidities. However, Richmond cautioned about significant implications.

Richmond shared that public health researchers have documented that many patients with higher weights do not perceive themselves as being overweight. Many clinicians and public health practitioners have blamed this misperception for why public health interventions have not resulted in meaningful outcomes. She detailed the common assumption that if the patient does not recognize weight as problematic, treatment interventions are destined to fail.

Richmond confirmed that some research supports this. One study showed that if patients accurately perceived themselves as overweight, they reported more weight-loss attempts. However, other research has shown that teenagers who were overweight and perceived themselves as so demonstrated fewer healthy behaviors (Hahn et al., 2018) and more internalized weight bias (Puhl et al., 2018); they reported more attempts at weight loss but actually gained more weight over time (Haynes et al., 2018).

Richmond also shared results from studies that suggested a protective effect of positive weight perceptions on health. A longitudinal study followed 20,000 people from grades 7–12 into their 40s. Teenagers who were overweight and held positive beliefs about their weight status were less likely to develop disordered eating behaviors (Hazzard et al., 2017; Sonneville et al., 2016a), had lower blood pressure later in life (Unger et al., 2017), fewer depressive symptoms (Thurston et al., 2017), and gained less weight over time (Sonneville et al., 2016b).

Richmond admitted that in the beginning of STEP, she and her team documented and notified patients of their weight, spending ample time trying to convince them that it was problematic. The team believed that this was the first step in motivating them to make changes, but in hindsight, this approach was inappropriate and pathologized their weight and body.

Surprisingly, Richmond said, patients pushed back. They expressed very positive feelings about their bodies. The teens said they would be willing to lose some weight so long as it did not change their shape, for example.

This experience led to some ethical questions for Richmond and her team. From the childhood obesity perspective, was it necessary or ethical to increase the child’s concern about their weight and make them feel bad about their body? From the eating disorder perspective, was it beneficial for children to feel good about their bodies despite being overweight? Was there something beneficial to them feeling quite good about their bodies?

To explore it further, Richmond’s research team surveyed 150 young adults at a university in the southern United States on body satisfaction, and researchers measured their height and weight. Participants also self-identified their body size using a body silhouette scale. Results showed that students accurately reported their BMI based on their self-reported height and weight versus that directly measured by researchers, with no difference

in accuracy based on their reported weight perception (i.e., self-reporting themselves to be just about the right weight versus having overweight or obesity). Furthermore, students who scored higher on body satisfaction scales were less likely to self-perceive as having overweight or obesity. Essentially, this study confirmed that individuals are accurate in understanding their weight status but may choose to consider themselves in a more positive light.

Returning to the AAP guidelines to communicate BMI to pediatric patients and their families, Richmond asked why clinicians would (re)tell them, if they are already aware of it. She argued that doing so risks introducing weight stigma and may be more damaging than helpful. Weight stigmatization, she defined, is negative or stereotypical beliefs and social devaluation of people living in large bodies. Weight is cited as the most common reason for youth bullying.

Richmond highlighted research that has shown the negative effects of weight bias and stigma. Psychological health is impacted by weight stigmatization, with greater prevalence of depression and anxiety, lower self-esteem, poor body image, and risk of substance abuse (Hunger and Major, 2015), more binge eating, greater caloric intake, more disordered weight control behaviors, less motivation to exercise, and decreased physical activity (Puhl and Suh, 2015). There are also physical or physiological health consequences of increased cortisol, C-creative protein, blood pressure, and HbA1C and less glycemic control (Tomiyama et al., 2018).

Richmond asserted that communication affects all patients, and weight stigmatization can lead to negative health outcomes in people living in larger bodies. It risks lower quality of care, with reports of contemptuous, patronizing, and disrespectful treatment when interacting with clinicians and health care systems (Alberga et al., 2019; Aldrich and Hackley, 2010; Phelan et al., 2015). Richmond detailed research showing that patients who experience weight stigma had poorer mental health status, increased disordered eating behaviors, and negative physiological health outcomes (Hunger and Major, 2015; Puhl and Suh, 2015; Tomiyama et al., 2018). Doctors are named the second most common source of weight stigma, she said.

Other research, Richmond continued, has shown that providers attribute all health issues to weight when assessing patients living in larger bodies. Physicians make assumptions about behaviors and assume they never exercise or are eating poorly (Alberga et al., 2019; Phelan et al., 2015). She mentioned reports of patients with a sore throat who are lectured about the value of weight loss and physicians spending less time in appointments and building rapport with patients who have overweight or obesity (Aldrich and Hackley, 2010; Phelan et al., 2015). They also receive less screening for cervical, breast, or colorectal cancer and are offered

fewer interventions (Aldrich and Hackley, 2010). Offices and hospitals lack right-sized equipment, such as cuffs to measure blood pressure and imaging machines, and have difficulty lifting and moving patients in the operating room (Aldrich and Hackley, 2010; Phelan et al., 2015).

Richmond stated that quality of care is negatively impacted because physicians are not trained to treat patients of various sizes. For example, as a medical student, she was trained to do a PAP smear on a 45-year-old fit White woman. Learning the procedure with someone of a different body size can impact the quality of care of individuals living in larger bodies, potentially contributing to disparities in health care for them.

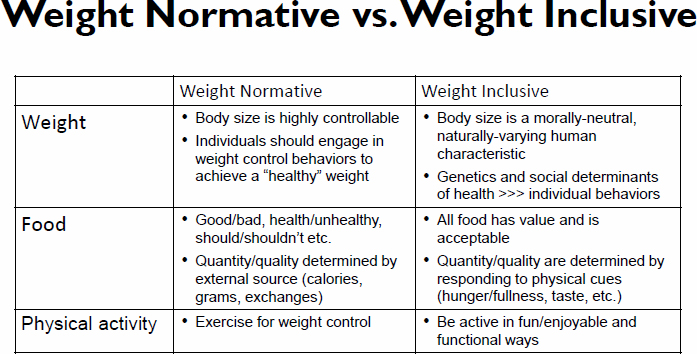

However, Richmond highlighted a paradigm shift among some clinicians for a weight-inclusive approach as opposed to the traditional weight-normative one (see Figure 8-1), which emphasizes weight loss to achieve health and well-being. Weight is the focal point for interventions, and body size is seen as controllable. Individuals are encouraged to engage in lifestyle changes and behaviors that will lead to weight loss, such as exercise. She detailed that food is considered categorically dichotomous as good or bad, healthy, or unhealthy, should or should not. People are expected to understand their needs based on calories or calorie exchanges.

In contrast, the focal points for intervention in a weight-inclusive approach are health behaviors and social determinants of health (SDOH) rather than an all-or-nothing focus on numbers (Association for Size

SOURCES: Presented by Tracy Richmond, June 26, 2023 (data from http://www.haescommunity.org; https://haescurriculum.com). Reprinted with permission.

Diversity and Health, 2020; Tylka et al., 2014; Weight Inclusive Nutrition and Dietetics, 2023). Body size is morally neutral and recognized as a natural varying human characteristic, so that people of all sizes, ability levels, and health statuses are accepted. Richmond emphasized the focus on genetics and the notion that all food is acceptable and that the quality and quantity of food are determined by taste and hunger and fullness cues.

Richmond encouraged clinicians to consider a weight-inclusive health care practice upheld by three tenets. The first is acknowledging a patient’s experience, which can build rapport. Higher-weighted patients likely have had stigmatizing experiences with health care professionals and are hesitant to interact again. Patients likely have tried to lose weight repeatedly, with frustrating results. They may have heightened sensitivity to conversations about weight. The second tenet is for the clinicians to communicate respectfully. They can ask if it is okay to talk about weight and weight-related topics and preferred terms to avoid stigmatization (e.g., “fat” versus “overweight” or “obese”). The last tenet is to focus treatment on behavior, not weight. Richmond emphasized that focusing on weight can contribute to a patient’s feelings of shame or frustration and promote extreme or unsustainable weight control strategies.

POVERTY, HEALTH POLICY, AND OBESITY

Martin Wilkinson, professor of politics and international relations at the University of Auckland, was the second presenter and focused on poverty and the uneven distribution of people with obesity among the population.

Wilkinson noted that in high-income countries, such as the United States and New Zealand, people with obesity tend to be low income. Although the distribution of body weight across a community varies by income, the goal would be to mitigate poverty to address inequity. Poverty is a problem in many countries, and several policy options exist to address it. Notably, he said, New Zealand has no farm subsidy policies or food deserts.

Wilkinson distinguished two ways that policy could try to solve the problem of poverty. One would be to give people money through a system that would equate to a welfare system or a labor market where people either have reasonable, secure, and predictable incomes or are ensured jobs that pay reasonably well. He contended that this is a complicated solution.

The second approach is by trying to supervise people’s choices, to discourage choices that are bad for them and encourage choices that are good for them. In the context of weight, one line of thinking is to make healthier options less expensive and easier to access. Alternatively, he said, a policy could make unhealthy options more expensive and less accessible through taxes.

One example Wilkinson gave was for a policy to tax sugar, as in the United Kingdom, or dietary fat, as in Hungary. Discouraging unhealthy foods could also be achieved by restricting promotions for junk food (e.g., “buy one, get one free”), restricting unhealthy product displays at stores, or zoning to prevent a high density of fast-food restaurants. These strategies aim to prevent people from purchasing unhealthy products and increase access to healthier products.

Wilkinson hypothesized that if a policy did not work or change behavior, it might increase inequities. For example, the goal of taxing sugar is to raise the price of sugary drinks to dissuade people from purchasing them. If it was ineffective, Wilkinson argued that people would be worse off because they would be paying more and still consuming the same amount of sugar.

Broadening the focus, Wilkinson offered a couple of observations on human behavior. The first is that health is not the predominant value that people equate to a good life. The second is that people often risk their health for another value. For example, Wilkinson highlighted grandparents who often play with their grandchildren, increasing their risk for getting sick. Similarly, professional athletes often set goals that increase their health risk.

In the context of food, Wilkinson noted an avocado shortage in New Zealand. Avocado prices increased to $5–6 USD. Healthy foods are often more expensive and take more time to prepare or cook. If you do not have the money or a kitchen, the alternative is eating unhealthy food that does not need to be prepared ahead of time.

Wilkinson returned to the issue of poverty and inequity. To solve the problem of poverty, he said, policy makers must reform the labor market or introduce a welfare system, and if that is not possible, they can try to change consumer choices and institute policies that influence their purchase decisions. The latter option, he said, could lead to inequitable choices with more expensive, convenient foods and less expensive, inconvenient foods.

COMMUNITY AND PUBLIC TRUST ASPECTS OF COMMUNICATION

The last speaker was Thomas Lee, internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, chief medical officer of Press Ganey, and professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. His presentation was about improving the patient–provider relationship by building trust, respect, and hope in the health care system and public system health.

Lee began by asking the audience to consider the elements of trust. What is it, and how do clinicians create it? According to Frances Frei’s The Trust Triangle, it is built with three components: empathy, authenticity, and logic (Frei and Morriss, 2020). He said that patients must believe the clinician has enduring empathy for them, is authentic and does not forget

them after the appointment, and has logic (is able to create a care plan). He emphasized that all three components are required to build trust in the provider or health care system.

For example, Lee shared his work using artificial intelligence and natural language processing to analyze over 2 million patient comments for concepts related to trust, respect, etc. The results showed 35,000 separate insights directly related to trust. He emphasized that patients want to trust their providers and the organizations they engage with.

Lee also noted that the results showed that trust was bidirectional (patients also need to understand that their clinicians trust them). For example, one patient commented that their doctor listened to them, validated their knowledge of their disease, and trusted that they knew their body and how they responded to treatment.

Similarly, Lee’s study found that a clinician’s failure to convey respect was associated with less trust. Its relevance to health care is that certain features are reliably present when patients have confidence in their provider. Courtesy and respect were especially important to underrepresented minorities in health care, he said. Respect was also found to be bidirectional.

Lee turned the discussion to the concept of hope. Clinicians can create a sense of hope in health care which, in his opinion, is part of quality of life that motivates behavior change. Hope theory has an initial idea of how circumstances will progress and a belief in a positive future. Lee posited that hope lies between what is likely to happen and what could happen. In the context of health, clinicians must have the skill and understand the path between where patients are in their health journey, where they are likely to go, and what might be possible.

Lee posed a question to the audience: how can clinicians and providers reliably offer hope to patients, particularly given no shared identity? To facilitate including hope in the care process, Lee and his colleagues developed a checklist for providers (Mylod and Lee, 2023).

Broadening the topic, Lee recounted the character and lessons of Confucius, who believed that rituals and frequent predictable moments where a person behaves as they should were important. Lee asserted that if a person performs the rituals, they would hone their instincts to anticipate other’s needs, gain their trust, give them hope, and motivate them to change their behavior to improve their health. The same is true for clinicians, he said.

PANEL AND AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

After each presentation, Austin led a question-and-answer discussion with the audience. The audience asked Richmond, Wilkinson, and Lee about when it is appropriate to discuss BMI with patients; public health

policies and commercial actors; nutrition assistance vouchers in the United States; and trust, respect, and hope in health care for people living in larger bodies.

Situations to Discuss BMI with Patients

The first question was for Richmond: “Could you share the situations in which discussing BMI would be appropriate?” Richmond emphasized that discussing BMI with patients is not all or nothing. Patients have different growth trajectories, so reviewing the patterns is important to look for any changes. Weight in eating disorders is relevant in terms of a pattern change or sudden weight gain. Similarly, a sudden change in weight could reflect a medication change or be an indicator of mental health. In the latter case, Richmond said, clinicians could build rapport and ask if anything has changed in their personal or professional lives.

Focusing on Public Health Policies with Awareness of Upstream Commercial Actors

An audience member commented on Wilkinson’s presentation, specifically about patients from historically marginalized groups, and respecting agency and autonomy for their health behaviors, even if they are unhealthy. What advice, they asked, would Wilkinson offer to public health professionals regarding policies and programs that respect people’s autonomy and maintain a focus on upstream influences, such as commercial actors or government policies that might limit choices? Wilkinson agreed that respecting agency and autonomy, particularly for those from historically marginalized groups, is paramount. He reiterated that his idea on autonomy was meant for making independent choices, whether good, bad, or in between. Regarding advice on dealing with upstream issues, clinicians must not fall prey to the politician’s syllogism: a problem exists, and something must be done that will not make people worse off than before. He urged the audience to seek evidence for people’s reactions to a policy. It is easier to justify stopping people from doing things they do not want to do versus what they do.

Nutrition Assistance Vouchers in the United States and Equity

Another question was about Wilkinson’s opinion about the restrictions for nutrition assistance vouchers in the United States. Are they equitable? Wilkinson responded that he considered them inequitable. Theoretically, the price is raised so consumers cannot buy a product, which is not equitable. He said people who are receiving assistance are among the worst off in society, and that is not their fault. The question is why not give them

more food and beverage options? They could receive money instead of the government offering to pay for healthy foods.

Austin agreed with Wilkinson about the tendency to gravitate toward nutrition-tied assistance as opposed to addressing underlying income inequities.

Trust, Respect, and Hope in Medicine, Clinical Care, and Society

The next question was for Lee: “How do the issues of trust, respect, and hope fit into national efforts to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion in medicine, clinical care, and society?” Lee responded that he thought these concepts were relevant, particularly since the murder of George Floyd; people have worked to understand the difference between treating people equally and the meaning of equity and inclusion. Many organizations have publicly shared their value system for equity, but implementation will take time. Treating people with respect does not cost money, but he asserted that executive leadership must realize the social capital for their entity, whether it be a nursing unit, a health care system, or a company.

Respect in the Medical System: Providing Care for People Living in Larger Bodies

An audience member commented that traditionally, in clinical care, providers thought it was respectful to be truthful and objective when informing patients about the severity and trajectory of their condition. A question for Lee was, what constitutes respect in the context of providing health care for people living in larger bodies? Lee replied that he learned a great deal from the other workshop presentations because of the diversity of speakers and perspectives that he had not been exposed to. Everyone has points of ignorance, he said, and feedback from different people decreases those.

Lee continued that health care delivery has large, institutional gaps in knowledge. For example, a medical school, an elite training program, is reluctant to accept students who have overweight or obesity. The underlying thought is that such a doctor may not help control a patient’s risk factors or be a good example. Lee pointed out that this is the equivalent of institutional racism built into the selection of medical students.

The first step he suggested is to acknowledge the issues. Much of the workshop focused on not offending patients. More important, he said, is for clinicians to have effective conversations with people who want to lose weight.

Equity in health care, Lee elaborated, would mean that all patients have a medical exam in the same room or physical space, using the same

equipment. He said that equity might be the point that Richmond made about right-sized chairs or blood pressure cuffs.

Lee asked, “What is the goal in health care?” Providers cannot deliver on immortality. The goal is for clinicians to help patients live as long and as well as possible and give them peace of mind that their health is as good as it can be given their circumstances. Lee recommended that clinicians make patients feel that they have listened to their story and concerns, they are respected and trusted, and their clinician is compassionate and trying to meet their needs.

Lee ended by stating that people are heterogeneous, and clinicians must try to meet them where they are to ensure peace of mind. To deliver patient-centered care to individuals, clinicians must understand their biases about different patients regardless of their identity.