Exploring the Science on Measures of Body Composition, Body Fat Distribution, and Obesity: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2024)

Chapter: 3 Tensions and Perspectives Around BMI

3

Tensions and Perspectives Around BMI

The second session was dedicated to body mass index (BMI) and the surrounding tensions in different contexts. Michael G. Knight, internist and obesity medicine specialist, medical director at the George Washington Medical Faculty Associates, and associate chief of quality and population health and assistant professor at George Washington University (GWU), moderated and introduced the panel, which had three presentations that detailed perspectives on the strengths and limitations of BMI in clinic, more broadly in public health surveillance, and from a patient’s lived experience. Knight concluded by leading a panel and audience discussion.

TENSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES AROUND BMI: A CLINICIAN PERSPECTIVE

Jamy D. Ard, professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Prevention and the Department of Medicine at Wake Forest University School of Medicine and codirector of the Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Weight Management Center, provided a clinician’s perspective on the routine use and value of BMI in clinics and the challenges of interacting with patients with regard to BMI.

Ard agreed that BMI is a screening tool, although he emphasized the lack of a reliable method to estimate fat mass in clinical practice. He asserted that the value of BMI as a measure of health risk must be interpreted alongside other health indicators in clinical practice. For example, Ard stated, weight trajectory is a more accurate indicator, regardless of BMI. Typically, he said, only wrestlers and pregnant people are actively or

intentionally gaining weight, so weight trajectory is more informative than a static BMI.

As a physician, Ard shared that it is standard clinical practice to use BMI cutoffs to determine treatment for a patient who has overweight or obesity. For example, a clinician may prescribe pharmacotherapy for patients with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 and one or more complications related to overweight, or for patients with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) provides guidance on the behavioral therapies for obesity treatment that are covered and reimbursable. Ard elaborated that Medicare beneficiaries pursuing coverage for intensive behavioral counseling and behavioral therapy for obesity must have a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater, for example (CMS, 2011).

Notably, Ard continued, CMS does not cover or reimburse clinicians for intensive behavioral therapy for someone without a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater. He highlighted the paradox for clinicians submitting claims for reimbursement to CMS and private insurers and using BMI as a directive for health care coverage. If a provider successfully treats a patient with a BMI of 31 kg/m2, theoretically, they may not be reimbursed once that BMI is 30 kg/m2 or lower.

Ard described the use of BMI in treatment allocation. Payers or employers typically do not cover treatment services for all payees or employees with obesity due to cost. Instead, he said, insurers create criteria or goalposts, and employers can choose to cover surgical treatment for individuals with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or higher or offer workplace wellness initiatives for all employees.

Ard reiterated the value of BMI as a diagnostic tool. It is standardized, easy to calculate, and found in the electronic health record (EHR). The challenge, he admitted, is the lack of distinction between type of fat or its distribution. As people age, he said, they lose lean body mass and gain fat mass; they can maintain their weight and BMI but have demonstrably different percent body fat. Even so, BMI is an integrated diagnostic criterion and required for treatment and reimbursement.

According to Ard, providers know that BMI means “body mass index,” and the cutoffs are broadly understood. BMI is associated with several clinical risk factors, including fat mass using dual X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) (R2 = 0.7–0.8), depending on the population. He added that it is not highly correlated with fat mass in special populations, such as football players or sarcopenic older adults.

Ard maintained that because BMI is integrated into the EHR, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), insurance treatment allocation, and indication, it is critical that clinicians have conversations with patients about it. However, he cautioned, patients do not have context or an understanding of BMI and hold various opinions,

yielding both the potential to cause harm and an opportunity to educate and engage them to focus on their health. Ard commented that many patients incorrectly assume they will be healthy once they achieve a “normal” BMI. He advocated for clinicians to use the opportunity to educate patients about their health risk and the prospect to reduce it immediately by initiating weight loss. Ard also acknowledged the patients who do not believe BMI applies to them because they are not White and suggested that clinicians refocus the conversation on health by affirming their concerns and asking if losing weight could be helpful.

Ard recapped that BMI is the long-term measurement and that, although BMI cutoffs define obesity as excess body fat, the real health risk is energy dysregulation. After all, if excess fat were the health concern, liposuction or body sculpting would be the optimal treatment.

BMI: A PUBLIC HEALTH PERSPECTIVE

Cynthia Ogden, an epidemiologist at the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and manager of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) analysis group, provided a public health perspective on BMI and discussed its strengths and limitations.

Ogden began by agreeing with Ard that BMI is a simple and inexpensive tool. It is strongly correlated with body fat at the population level and useful to observe trends over time (Hales et al., 2018). Conversely, she said, it is not a direct measure of body fat and does not capture fat distribution or distinguish between fat and lean body mass. Furthermore, the association between BMI and adiposity or health outcomes varies by ethnic group.

Obesity definitions can vary. Ogden stated that children and adolescents have different reference populations around the world, with considerable variability between country-specific charts, World Health Organization (WHO) growth standards for birth to 5 years and 5–18 years, International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) cutoffs for children aged 2–18, and CDC growth charts, with gender-specific BMI cutoffs that vary by age. U.S. adult obesity and severe obesity are defined by cutoffs of 30 kg/m2 and 40 kg/m2, respectively. Conversely, in China, obesity is defined by a cutoff of 28 because of an increased health risk (Zeng et al., 2021).

Ogden noted that obesity prevalence varies based on the chosen BMI cutoffs and whether height and weight is self-reported or measured. For example, trained professionals measure the height and weight in NHANES and enter these directly from the stadiometer and scale into the database. From 2017 to March 2020, NHANES results showed that nearly 42 percent of people in the United States had obesity (Stierman et al., 2021). Data

from the 2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), Ogden reported, which is based on self-reported height and weight, showed only 31.9 percent (CDC, 2020). Ogden indicated that the discrepancy was due to people overreporting their height and underreporting their weight.

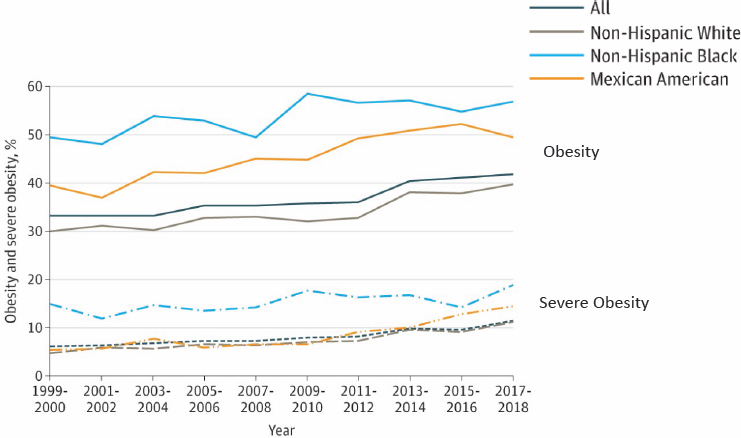

A strength of BMI, Ogden stated, is its epidemiological use for obesity surveillance over time overall and for different groups and geographic locations. Regardless of the chosen cutoffs, trends emerge when the same cutoff is used. Illustrating the strength of BMI, Ogden shared a graph of increasing trends in age-adjusted obesity and severe obesity among women by race and ethnicity between 1999 and 2018 (Ogden et al., 2020) (see Figure 3-1). Ogden added that it is also useful to observe changes in the population distribution of BMI.

BMI is also limited, Ogden conceded, and can mischaracterize body fat. For example, in an NHANES study of girls aged 8–19, Black girls had a significantly greater prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) when compared to White and Mexican American girls, but no significant differences were found when adiposity was measured with DEXA scans (Flegal et al., 2010). Similarly, other research using NHANES data found inconsistent distributions of body fat and BMI for U.S. boys aged 8–19 between racial and ethnic groups (Martin et al., 2022).

SOURCES: Presented by Cynthia Ogden, April 4, 2023. Reproduced with permission from Journal of the American Medical Association. 2020. 324(12):1208-1210. Copyright ©(2020) American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Furthermore, Ogden shared, BMI is also variable as an indicator for the prevalence of diabetes. In the U.S., obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) is more prevalent among White adults, at 41.4 percent compared with just 16.1 percent of Asian adults (Stierman et al., 2021). Even so, the percentage of Asian adults diagnosed with diabetes was similar to White adults (CDC, 2022).

Ogden summarized some key considerations for BMI in public health monitoring and surveillance. First, she said, the cutoffs vary, and among children and adolescents, different age- and sex-specific reference populations are used. Next, BMI is most useful for monitoring population trends. Third, self-reported weight is underreported and height overreported, which leads to lower BMI. Finally, Ogden reminded the audience of the variability between racial and ethnic groups concerning the relationship of BMI with body fat or diabetes diagnoses.

LIVED-EXPERIENCE PERSPECTIVE

Stacy E. Wright, a Ph.D. student in the Health Outcomes and Implementation Science Program at the University of Florida, rounded out Session 2 by recounting her experience with the Jamaican and U.S. health care systems from childhood to adulthood.

Wright opened by emphasizing the stress she felt as a child about her body and appearance and its impact on her mental and physical health. She learned early on to focus on her excess weight and not health risks. She was a competitive swimmer and ballet student as a child, but her parents worried about her body size and monitored and criticized her eating habits; despite her eating habits and appearance, blood tests verified that she was metabolically healthy.

Wright described her experience of being shamed and stigmatized and having her accomplishments minimized. She internalized comments and pseudo-compliments about her weight: “You are pretty for a fat person.” Wright recalled an incident at a high-jump competition at school that shaped her self-esteem and self-worth. She was a finalist, and a spectator called her a “fatty,” causing the crowd to laugh at her. After that, she refrained from activities that would put her at risk for being teased and focused on her academic work.

Wright admitted that in private, she was obsessed with fashion magazines and convinced that her life would be better in a thin body and that she would be normal. She saw reminders about the value of thinness everywhere in her environment. Stores had countless mirrors and a limited range of clothing sizes. She was teased and bullied about her size by strangers and felt intense anxiety about certain spaces and objects that could not accommodate her weight. She recalled that these experiences led her to diet for weight loss in young adulthood.

At 28 years old, she was diagnosed with hypertension, and it prompted her to improve her eating habits and increase her physical activity. She learned about nourishing foods and strived for a lower body weight range to avoid a lifetime of taking medication for hypertension. Wright lost over 100 pounds and is almost within a normal BMI range, though her weight continues to fluctuate by 10–20 pounds. Since then, she has been working with a team of doctors who are focused on her progress and health and not BMI. Her blood pressure is under control.

Wright ended by encouraging providers to seek continuing education on weight bias and discrimination, improve patient–provider communication, and approach patients as individuals with unique experiences, knowledge, and goals.

PANEL AND AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

A moderated panel discussion was led by Knight at the end of the second session. Questions from the audience to Ard, Ogden, and Wright encompassed alternatives to BMI to monitor obesity at the population level; using BMI in the clinical setting; communicating with patients about weight, BMI, and health; fostering open dialogue between patients and their providers; and using BMI as a threshold to determine treatment modalities.

Alternative Measures to Monitor Obesity at the Population Level

Referring to Ogden’s presentation on the strengths and limitations of BMI as a measure of obesity, Knight asked Ogden to comment on alternative measures for monitoring at the population level. Ogden emphasized that the challenge of replacing BMI is its simplicity and affordability. Moreover, for obesity at the population level, different datasets have advantages and disadvantages. BRFSS captures state and county-level data on BMI and obesity but uses self-reported weight and height, which is less accurate. NHANES offers a national snapshot of obesity and BMI and periodically measures body fat using DEXA scans, which are accurate but require training and are expensive and time consuming.

Utility of BMI in the Clinical Setting

Knight turned the discussion to Ard’s presentation on the clinical perspective of BMI and asked how clinicians could best use it. Ard reiterated that, paired with BMI, weight trajectory is essential to integrate into a clinical assessment for obesity. After a year of treatment, Ard continued, some patients return to their physician with significant weight loss, and if clinicians only consider BMI, they will likely emphasize the need to lose more

weight. He argued that integrating weight trajectory tells a story. EHRs show a change in weight and BMI at each doctor’s visit and could integrate with other health indicators, such as the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk score that calculates a 10-year risk for a cardiovascular event (e.g., stroke). Ard continued that other information could be useful to determine health-related risk, such as sleep apnea, family history, social determinants of health (SDOH), and the EHR could ideally synthesize the data for the clinician.

Communicating with Patients About BMI, Weight, and Health Risk

Knight noted the challenge of communicating with patients about BMI and health risks from Wright’s presentation. He shared that in his experience, clinicians consider 5–7 factors when assessing a patient’s adiposity and health risk, which can be challenging to explain to a patient versus a straightforward BMI cutoff. Knight asked Wright to comment on how clinicians can better explain their clinical judgment of BMI to patients.

Knight responded that clinicians could use layperson terms to foster an open dialogue about BMI and related health risks because patients do not have the same knowledge or language as clinicians and are intimidated. Wright suggested that they spend time with people and focus on establishing a rapport because communication is unique to the situation. She added that they could shift away from “overweight,” “fat,” or “obesity,” which have negative connotations.

Improving the Distinct Interactions of Patients and Providers

An audience member noted the importance of individual care and the time that clinicians need to build a relationship and asked Ard to comment on what he thought it would take to train clinicians to make patient–provider interactions more positive and holistic. Ard responded that the health care system needs to change. He highlighted that insurers and payers pay providers and clinicians not to improve health but to see more patients. Providers need more time during appointments and also a more efficient way to integrate data in the EHR to understand patients over time and in the context of their health history.

BMI as a Threshold for Treatment Modalities

The last question, from an audience member, was about whether BMI should still be a threshold for treatment modalities, such as medication or surgery. Ard acknowledged that the question suggested that BMI should not be a threshold and that clinicians must use their medical judgment to

understand the modality. Nevertheless, he noted practical cost issues and the cultural phenomena of thinness. Furthermore, having treatment available for everyone who could afford it would cause ethical and resource challenges along socioeconomic lines.