Exploring the Science on Measures of Body Composition, Body Fat Distribution, and Obesity: Proceedings of a Workshop Series (2024)

Chapter: 5 Looking Ahead

5

Looking Ahead

The fourth and final session was moderated by Nico Pronk. He introduced the three panelists, whose presentations focused on an equity approach to address weight stigma, measuring success in obesity treatment, and the path forward for clinically assessing patients for obesity. He then led a panel and audience discussion.

Pronk reminded participants of the paradoxes surrounding body mass index (BMI) and obesity. Obesity diagnosed with BMI leads to broadly characterizing an endemic health problem that is socially and financially impervious. Pronk recalled that despite excess weight and elevated BMI, some people are metabolically healthy and show no limitations in activities of daily living. Yet, at the same time, the evidence clearly shows that obesity is associated with distinct pathophysiological alterations of tissues and organs, clinical signs, and symptoms, increasing the risk of secondary complications and multimorbidity. Obesity, defined as a disease, also justifies the need for access to medical treatment and care and may reduce weight-related bias and stigma.

Based on Stacy Wright and Faith Anne Heeren’s presentations about their lived experiences, clinicians critically need to frame obesity and related measurements in the context of a patient’s experience and focus on health risks, not weight. The challenge is to move beyond the relationship of BMI in defining obesity and its diagnosis, social and clinical implications, and patient experience.

AN EQUITY FRAMEWORK APPROACH TO CHART NEEDED ACTION

The first presenter was S. Bryn Austin, who shared that her presentation would focus on weight stigma and discrimination using Shiriki Kumanyika’s Framework for Increasing Equity Impact in Obesity Prevention (Kumanyika, 2017), which is designed to guide interventions to reduce disadvantage and improve equity. She began by presenting a definition of health equity:

Health equity means everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. This requires removing obstacles to health, such as poverty, discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness and a lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education, housing, safe environments, and health care. (Braveman et al., 2017)

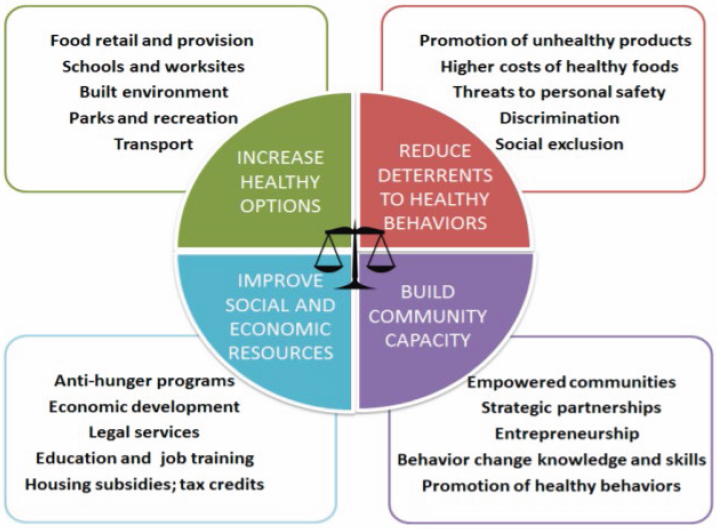

Austin explained she used the upper right quadrant of the framework to focus on policy and systems change interventions for people living in large bodies (Kumanyika, 2017, 2019) (see Figure 5-1). She discussed two

SOURCES: Presented by S. Bryn Austin, April 4, 2023. Kumanyika (2017). Reprinted with permission.

approaches to address equity issues and mitigate weight stigma and discrimination: legal action and eliminating barriers to care.

Austin presented background and evidence to demonstrate the severity of weight stigma and discrimination and the threats to personal safety for people living in larger bodies. She shared research documenting social exclusion and isolation, such as inaccessible public settings, and a myriad of attacks, including assumptions of negative characteristics, work-related discrimination associated with lower earnings, a lower probability for professional and educational advancement, a greater likelihood of being fired, and lower ratings by school teachers and college admissions professionals.

Austin detailed how these inequities significantly impact mental well-being and physical health, with a greater risk for depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and physiological stress and harmful physiological effects, such as the allostatic load or “wear and tear on the body” in response to discrimination.

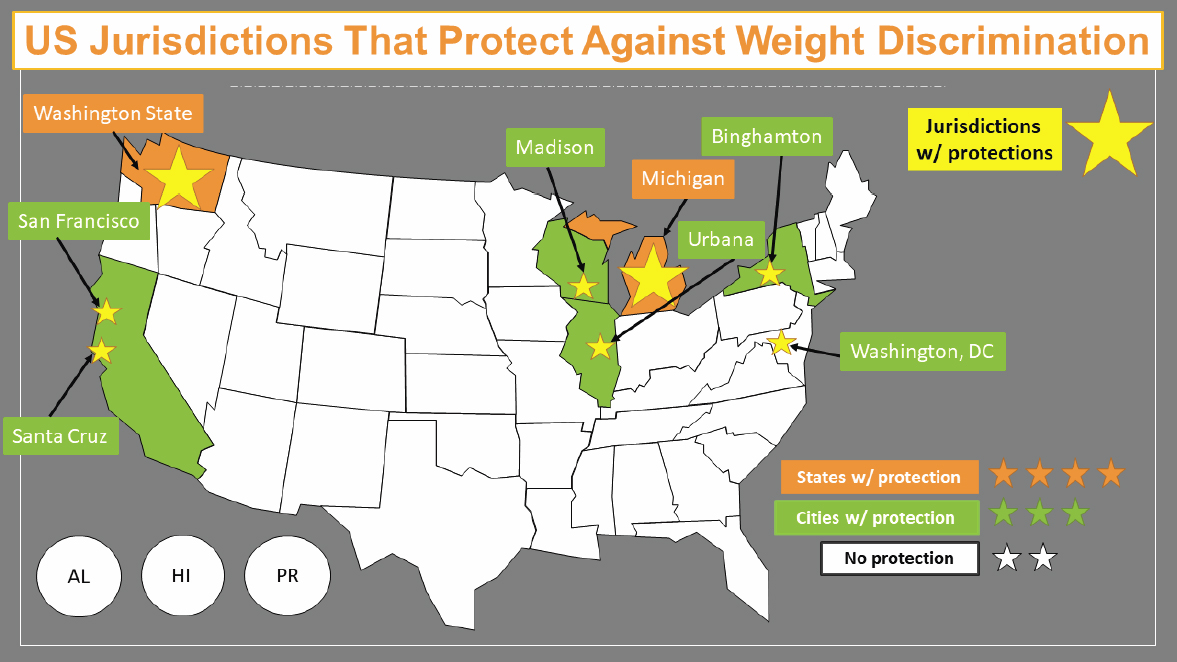

Austin called out the widespread and legal weight discrimination in the United States, which is an obstacle to basic rights and health for people living in larger bodies (UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy and Health, 2017). She estimated that approximately 96 percent of people residing in the United States are in areas with no legal protection from weight discrimination.

Widening the scope to a macro level, Austin emphasized the societal and economic consequences of weight discrimination. Her research group, the Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders (STRIPED), along with Deloitte Access Economics and Dove, authored a collaborative report on the social and economic cost of weight discrimination in U.S. society (Deloitte Access Economics, Dove, and STRIPED, 2022) that estimated that weight discrimination leads to an annual recurring cost of about $200 billion in the health system with productivity loss, wage loss, and employment loss.

Austin suggested banning weight discrimination to address the equity issue of discrimination and social exclusion. She pointed to a policy brief:

Without laws to prohibit weight discrimination, people will continue to be unfairly fired, suspended, or demoted because of their weight, even if they demonstrate good job performance and even if body weight is unrelated to their job responsibilities. (UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy and Health, 2017)

Austin acknowledged the progress in passing antidiscrimination laws in Michigan and Washington state to protect people living in larger bodies (see Figure 5-2). She also highlighted that in the Massachusetts state legislature, Senator Rebecca L. Rausch and Representative Tram T. Nguyen have introduced legislation that prohibits discrimination against body size.

SOURCE: Presented by S. Bryn Austin, April 4, 2023. Reprinted with permission.

Austin continued by offering a second approach to address inequity and threats to personal safety from discriminatory practices affecting people living in larger bodies by expanding access to health care and eliminating barriers. The primary challenge, she admitted, will be to determine and agree on the barriers and strategies to remove them. One example of a barrier, Austin said, is the universal routine of weighing and BMI surveillance. She asked audience members to consider if universal weighing is a barrier to care. She noted that measurement of weight and BMI are ubiquitous in society, including in health care, online, in digital apps, at school, at work, and in athletics (Alberga et al., 2019; Austin and Richmond, 2022; Phelan et al., 2015; Richmond et al., 2021).

Austin suggested applying a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats (SWOT) analysis to the idea of universal weighing or BMI surveillance. It is meant to systematically assess factors that may be helpful or harmful to a project and undermine or promote its success (AHRQ, 2021; Blayney, 2008; Minnesota Department of Health, 2021). Referring to universal weighing and BMI surveillance, she reminded participants that BMI is a poor health indicator and is used to justify persistent discrimination against people living in large bodies and disproportionately, minority communities.

Austin detailed the SWOT of universal weighing. The strengths include dosing medications, child health care and tracking their growth, and targeting efforts to improve public health and equity. She outlined opportunities that include being alerted to the impacts of interventions, societal trends, and inequities. However, she said, it also has clear weaknesses. Specifically, BMI is an unreliable proxy for individual health. Last, threats include widespread weight stigma that can cause a person to experience shame, avoid clinicians, and have poor health as a function of fewer health care visits and monitoring.

Austin urged the audience to consider where, how, and why routine weighing should be required or encouraged. How might practices disproportionately burden BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color), low-income, and other minoritized communities receiving care through public systems? Austin advocated for clinicians to build relationships with their patients prior to discussing weight and concluded her talk with a quote from a physician in Washington, DC:

I delay weighing new patients so I can make sure doing so would not cause harm, like in the case of clients with eating disorders or a history of body shame.

OBESITY TREATMENT: HOW TO MEASURE SUCCESS FOR PUBLIC HEALTH

Craig M. Hales, clinical reviewer for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Division of Diabetes, Lipid Disorders, and Obesity (serving in a personal capacity), was the second presenter. Hales emphasized that despite effective treatments available for obesity, it is not yet clear how to measure success for public health, as is the case for other chronic conditions.

Hales gave the example of hypertension. The goal of diagnosis and treatment is a specific blood pressure target, which is referred to as “controlled hypertension.” With hypercholesterolemia, the goal is maximal atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk reduction. For diabetes, the goal is a specific glycemic target. However, obesity has the unresolved question of how to define the goal of treatment.

Hales then reviewed four clinical guidelines for treating obesity. He began with the algorithm from the 2013 recommendations from American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society, which defines successful treatment as weight loss ≥5 percent, sufficient improvement in health targets as determined by the patient and clinician, and weight loss maintenance (Jensen et al., 2013). The Obesity Medicine Association’s overall management goals for adults are to improve health, quality of life, and body weight, stating that 5–10 percent weight loss may improve metabolic disease (Tondt et al., 2023). He elaborated on the Endocrine Society’s clinical guidelines on the pharmacological management of obesity, which mention ameliorating comorbidities and amplifying adherence to behavior changes, which may improve physical functioning and allow for greater physical activity (Apovian et al., 2015). For the pediatric population, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guidelines indicate that a key is to monitor and treat comorbidities concurrently (Hampl et al., 2023). Furthermore, Hales added, AAP details the need for long-term data to establish weight loss and cardiovascular improvements impacting health into adulthood.

Hales moved on to discuss Healthy People 2030, which is a data-driven set of national objectives based on clinical guidelines to improve health and well-being over 10 years. To monitor progress toward the goals, a public health surveillance metric derived from clinical guidelines is required, although the various guidelines have no consensus on how to define successful obesity treatment as they do for other chronic conditions.

Hales then examined the public health surveillance metrics in Healthy People 2030 for other chronic conditions (Healthy People 2030, n.d.). For hypertension, an objective is to reduce the proportion of adults with high blood pressure, defined as systolic ≥130 mmHg or diastolic ≥80 mmHg, or taking an antihypertensive medication. Another objective is to increase the

rate of blood pressure control for adults, which is defined as a systolic blood pressure <130 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure <80 mmHg. For hypercholesterolemia, Hales noted two objectives in adults: (1) reduce mean total blood cholesterol level in the population and (2) increase the rate of treatment among adults for whom a statin is recommended. For diabetes, the objectives are to (1) reduce the number of cases diagnosed annually and (2) reduce the proportion of adults with diabetes who have a hemoglobin A1c >9 percent.

However, in reviewing the Healthy People 2030 for overweight and obesity, Hales noted that the overall goal is to reduce both by helping people eat healthy and become physically active. He detailed three objectives: reduce the proportion of children and adolescents with obesity, reduce the proportion of adults with obesity, and increase the proportion of health care visits by adults with obesity that include counseling on weight loss, nutrition, or physical activity. The third objective addresses treatment but is a process measure and does not capture any health outcome that reflects successful management. For example, someone might be treated successfully and become metabolically healthy, but their BMI, as captured by public health surveillance, would categorize them simply as having obesity.

LOOKING AHEAD: CLINICAL ASSESSMENT OF OBESITY

Michael Knight was the last presenter. He provided a clinical perspective on defining obesity as a multifactorial disease. He opened by noting its many definitions, such as the following:

A chronic, relapsing, multifactorial, neurobehavioral disease wherein an increase in body fat promotes adipose tissue dysfunction and abnormal fat mass physical forces, resulting in adverse metabolic, biomechanical, and psychosocial health consequences. (Obesity Medicine Association, 2017)

Knight shared that his patients often seek medical care for weight management. However, they list reducing their BMI as their health goal. Knight emphasized that the key to identify their goals is building a relationship, building trust, and coming to a shared understanding.

After all, Knight reiterated, BMI does not reliably predict adiposity. Some of his patients have an elevated BMI and no excess adiposity; others refuse to discuss weight because no one in their family has ever aligned with the BMI number. Still others have a lower BMI and metabolic dysfunction, underscoring the importance of assessing the whole patient, by listening and learning about their experiences.

As a clinician, Knight focuses on improving health outcomes, longevity, quality of life, and years of life to identify individuals with the greatest risk for morbidity and mortality. He introduced the Edmonton Obesity Staging

System (EOSS) as a useful framework to prioritize and predict health risks. It comprehensively assesses an individual and ranks the severity of obesity based on a clinical assessment of weight-related health issues.

A clinical diagnosis, Knight underscored, is an assessment of the whole person. For example, he said, a patient with diabetes and an HbA1C of 7.1 percent and no other issues will receive different medical treatment for diabetes management than a patient with an HbA1C of 6.9 percent who recently had a stroke and a myocardial infarction. Knight stated that HbA1C is only a number, like BMI. Similarly in hyperlipidemia, clinicians assess the risk for ASCVD, whereas they used to work with patients to achieve an LDL cholesterol under 130 mg/dl.

Knight asserted that the challenge is that BMI cutoffs direct treatment options (e.g., medication, surgery) and insurance coverage and clinician reimbursement. The functional component of obesity, meaning mechanical issues, such as joint pain and fatigue, can be significant despite no single reliable functional measure. Knight summarized that if a clinician only reviews a patient’s BMI, the link to their health risk is missing.

PANEL AND AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Pronk began the panel discussion. The audience asked the panelists questions about weight stigma and discrimination in the clinical setting; measuring success of obesity treatment; conversations with patients about BMI and its limitations; and reframing BMI as a vital sign and how to discuss its purpose with patients.

Addressing Weight Stigma and Discrimination in the Clinic

Pronk began by commenting to Austin about her talk on weight stigma and discrimination and policy implications. What can scientists and clinicians do to address these issues? Austin responded that scientists could address weight stigma by refraining from weighing patients at every visit. She recommended that clinicians talk with their patients about their experience with weight stigma to build a relationship for open dialogue. Austin also suggested that scientists and clinicians could promote and amplify the national anti-stigma campaign by the Obesity Action Coalition (OAC, 2023). Scientists and clinicians can also provide testimony and expertise to policy makers and their staff for evidence-based policy, she said.

Measuring Success in Obesity Treatment

An audience member commented on Hales’ experience in the clinic and in public health and asked for his opinion on a measure for the success

of obesity treatments. Hales said that he did not have a definitive answer, but it was instructive to consider the measures of success for other chronic conditions. One of the Healthy People objectives for hypertension defines the condition not only by blood pressure measurement but by recognizing that an adult may have been successfully treated, which is also a relevant concept for obesity.

Patient–Provider Conversations About BMI and Its Limitations

Knight received a question about how clinicians and providers could approach the conversation with patients about BMI and its limitations. Knight offered that many patients do not understand what BMI indicates other than it is a number reported during every clinic visit. Health care professionals could begin a conversation by explaining the reason for calculating BMI, what it screens for, and why it is not a health outcome. Knight advocated for clinicians to provide a foundational knowledge for context, give patients the ability to learn about their conditions and progress, and empower them to set personal goals. He urged clinicians and providers to consider BMI as a vital sign, like blood pressure.

Destigmatizing BMI as a Vital Sign: Conversations with Patients About Its Purpose

An audience member and clinician responded to Knight’s comment to destigmatize BMI and frame it as a vital sign. How can clinicians and providers do so? Austin responded by reminding participants that she is not a clinician. She noted that everyone is weighed immediately at medical centers for any condition and advocated for refraining from doing so unless necessary, because it causes some patients to avoid medical centers, and that clinicians establish a rapport with a patient before weighing them.

Knight added that many patients do not understand the need for a weigh-in at every doctor’s visit. Patients report that BMI or weight is sometimes but not always mentioned. Still, at other times, he said, the doctor may passively comment on a patient’s need to lose weight without offering actionable steps. In weight-management clinics, weighing in is not an issue because patients are seeking weight-related services. Knight advised that if clinicians measure BMI, they must have a plan to address it.

CLOSING REMARKS

Ihuoma Eneli began by recalling that the planning committee chose the topics of BMI and the definition of obesity because of special interest among the U.S. public, as highlighted by the media. In 2021, several

articles appeared on the limitations of BMI, including one in the February issue of Good Housekeeping on “The Racist and Problematic History of Body Mass Index” and one in The Washington Post on “Why BMI Is a Flawed Health Standard, Especially for People of Color.” Eneli added that the Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology Commission on the Definition and Diagnosis of Clinical Obesity was formed to gain consensus after reviewing the evidence for BMI and its role in defining obesity from the scientific and lived-experience perspectives; the final report will have substantial implications for the field, domestically and internationally. Eneli also pointed to the AAP guideline (January 2023) that outlines key actions for clinicians to discuss BMI or BMI percentile as a screener for health with patients and their families and use BMI percentile to assess the patient for risk factors for other conditions.

Eneli recapped the workshop that explored the science of body composition and body fat distribution measures and focused on the strengths and limitations of BMI as a measure of adiposity and health. She highlighted that the speakers examined the utility of alternative measures to assess obesity, morbidity, and mortality and their practical implications on defining obesity in health care, public health, and the legal field for prevention and treatment.

Eneli noted the points of agreement among scientists and clinicians. BMI measures body size and not body health. It is a surrogate measure of body fat and a screening tool with some reliable strengths, she added. It is simple to calculate, inexpensive, noninvasive, and highly familiar to patients, providers, and the public. She also emphasized that BMI is a standardized and objective measure that correlates with body fat and tracks the growth of children and population trends. Eneli reasoned that because of its strengths, BMI guides treatment options and reimbursement from insurers and serves as an objective endpoint in clinical trials.

Eneli also pointed to several limitations of BMI, underscoring that it is not a direct measure of body fat and does not capture fat distribution. It does not distinguish between lean body mass and fat mass, and evidence is lacking to support the cutoffs to define obesity, all of which have implications for different population segments. She stated that the association between BMI and body fat varies by race, ethnicity, and age. Moreover, in patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, a change in BMI is not indicative of changes in body fat. She added that BMI does not measure fat cell size, a developing measure for dysfunction. These inconsistencies have led to patients misinterpreting BMI, which also happens in health care, by employers, and in public health. The downstream effect is its contribution to weight bias and stigma, which are key elements of discrimination that impact public health and quality of life.

Eneli continued that the evidence presented at the workshop revealed that adipose tissue distribution in the visceral or ectopic areas versus subcutaneous tissue may be more predictive of metabolic disease or unhealthy obesity than BMI. Furthermore, she said, a genetic predisposition determines fat distribution through human biology and hormones, which vary by race, ethnicity, and age and account for differences in obesity and comorbidities across groups. Accordingly, BMI and visceral fat are moderately correlated.

Eneli highlighted other research presented that demonstrated the correlation between the size of adipocytes or fat cells and their functional capabilities. Studies showed that the larger the adipocyte, the greater the risk for dysfunction and metabolic health consequences. She recalled the example of a patient with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 and healthy lab results with low cholesterol and noted a moderate and insignificant correlation between BMI and the size of fat cells.

Eneli discussed the alternative measures to BMI, which are limited by their accuracy and cost. Digital anthropometry is more indicative of health, although clinical trials need to test its reliability. She noted that waist circumference is a better measure and predictor of health, but providers/patients are uncomfortable when administering/enduring the measurement. Dual X-ray absorptiometry is more accurate than BMI, but it is cost prohibitive.

Eneli referred to the outstanding questions, tensions, and opportunities for future research. What is the physiology and pathophysiology of adipose tissue, and how does it help to define obesity? Does the available evidence support the cutoffs? Given the limitations of BMI, she questioned whether it should be eliminated or used for specific purposes. How are BMI and alternative measures interpreted in the clinical setting, health care, and public health? What are the potential implications of the alternatives regarding weight bias and stigma, cost, and society? How do clinicians communicate about the physical and psychosocial health considerations with a high BMI in policy, public health, and health care?

Eneli concluded by affirming that health is not merely the absence of disease and that obesity is not only about cardiometabolic health. Obesity affects physical health, mental health, and quality of life. She encouraged participants to return for the second workshop of the series (June 2023) on novel approaches to improve communication about body composition, BMI, adiposity, and health across diverse groups and sectors and strategies to mitigate disinformation and misinformation and identify research gaps and potential next steps to advance the field in research, clinical practice, and public health policy.

This page intentionally left blank.