Active Traffic Management Strategies: A Planning and Evaluation Guide (2024)

Chapter: 2 ATM Strategies

CHAPTER 2

ATM Strategies

Chapter Highlights and Objectives

This chapter provides a high-level overview of the specific active traffic management (ATM) strategies included in the guide and discusses successes in both the United States and overseas. The remainder of this chapter presents the following sections:

- ATM Defined. A concise definition of ATM and a list of the strategies included in the guide.

- ATM Strategies. A brief overview of each ATM strategy is included in the guide and specific information related to how and where each might be deployed.

- ATM Successes. Highlights of both domestic applications and global experiences with ATM strategies.

- Final Remarks. Final remarks for the chapter discussing the ATM strategies included in the document.

- Chapter 2 References. A list of all references cited within the chapter.

ATM Defined

ATM is the ability to manage recurrent and nonrecurrent congestion dynamically and proactively on an entire facility based on real-time or predicted traffic conditions (FHWA 2012). ATM strategies rely on the use of integrated systems with new technology and focus on trip reliability. ATM strategies maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of a facility while increasing throughput and enhancing safety.

ATM is the ability to dynamically and proactively manage recurrent and nonrecurrent congestion on an entire facility based on real-time or predicted traffic conditions.

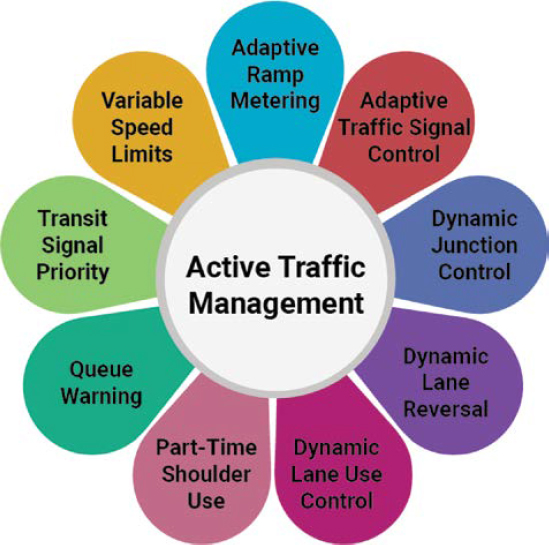

One of the benefits of these systems is that they allow for the dynamic or real-time automated operation of traffic management strategies that more quickly respond to changing conditions as they occur. Figure 2-1 presents the ATM strategies that form the foundation of the ATM concept that is included in this guide: adaptive ramp metering, adaptive traffic signal control, dynamic junction control, dynamic lane reversal, dynamic lane-use control, part-time shoulder use, queue warning, transit signal priority, and variable speed limits. General information related to ATM is also included on the FHWA active traffic and demand management (ATDM) website (FHWA 2023a).

The Active Management Continuum

Active is the key operational descriptor of ATM. The inherent dynamic nature of ATM acknowledges the use of near-real-time information from the infrastructure, which allows an agency to manage and change the deployment as needed. Additionally, the active management

(Source: TTI).

of the system lies on a continuum that moves from straightforward time-of-day operations to a truly comprehensive and proactive approach (see Figure 2-2).

The four levels can be described as follows (FHWA 2023c):

- Level 1: Static—Strategy responses to variations in conditions are preset and updated based on the calendar (periodic review and update), policy, or law.

- Level 2: Reactive—Strategy responses change when an agency observes problems with the static plans; involves limited, if any, real-time monitoring.

- Level 3: Responsive—Strategy adjustments occur in real time in response to changing conditions.

- Level 4: Proactive—Strategy responses are adjusted in anticipation of future conditions.

As agencies consider ATM for their facilities, it is important to acknowledge that working with existing capabilities can be a great starting point for ATM strategy operations. As capabilities advance, the ability to actively manage an ATM strategy will advance as well. Furthermore, an agency does not necessarily need to be at the far end of the active management continuum to effectively implement an ATM strategy and realize safety and mobility benefits from the deployment. Specific example characteristics for each stage of the active management continuum and each ATM strategy are provided in Table 2-1.

(Source: Adapted from FHWA 2023c).

Table 2-1. Active management continuum for ATM strategies.

| ATM Strategy | Static | Reactive | Responsive | Proactive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Ramp Metering | Deploy pretimed or fixed-time ramp metering during peak periods. | Monitor and manage existing lanes and ramps and manually adjust use based on incidents or other conditions. | Utilize responsive ramp metering based on current demand on a 24/7 basis. | Employ 24/7 automated operations of ramps using current/predicted levels of traffic and incidents. |

| Adaptive Traffic Signal Control | Deploy pretimed or fixed-time signal timing and progression strategies based on time of day. | Provide actuated-coordinated operations to provide unused green times from underutilized phases to heavy-demand movements. | Select signal timing plans in real time based on specific conditions or system performance thresholds on a 24/7 basis. | Dynamically adjust traffic signal timing plan parameters in real time based on measured traffic conditions. |

| Dynamic Junction Control | Deploy junction capacity changes during peak periods. | Monitor and manage existing lanes on freeways and key connectors and manually adjust use in response to incidents or special events. | Implement responsive junction control based on current demand on a 24/7 basis. | Employ 24/7 automated operations of junction control using current/predicted levels of traffic and incidents. |

| Dynamic Lane Reversal | Deploy lane reversal operations during peak periods. | Monitor and manage existing lanes and manually reverse lane use based on incidents or other conditions. | Implement dynamic lane reversal based on current demand on a 24/7 basis. | Operate automated dynamic lane reversal on a 24/7 basis using current/predicted levels of traffic and incidents. |

| Dynamic Lane-Use Control | Deploy lane-use control during peak periods. | Monitor and manage existing lanes and manually adjust lane use based on incidents or other conditions. | Implement dynamic lane-use control based on current demand on a 24/7 basis. | Operate automated dynamic lane-use control on a 24/7 basis using current/predicted levels of traffic and incidents. |

| Part-Time Shoulder Use | Deploy shoulder-use operations during peak periods. | Monitor and manage existing lanes and manually open shoulders based on incidents or other conditions. | Implement responsive shoulder use based on current demand on a 24/7 basis. | Deploy 24/7 automated operations of shoulder use using current/predicted levels of traffic and incidents. |

| Queue Warning | Deploy queue warning during peak periods. | Monitor and manage existing lanes and manually deploy queue warning signs based on incidents or other conditions. | Implement responsive queue warning based on current demand on a 24/7 basis. | Deploy 24/7 automated queue warning operations using current/predicted levels of traffic and incidents. |

| Transit Signal Priority | Deploy transit signal progression where coordination parameters are set based on realistic travel speeds for on-street transit (NACTO 2016). | Coupled with short, dedicated transit facilities, monitor and manage traffic signal timing to provide transit vehicles to enter traffic flow in a priority position. Example: queue jumping lanes with leading bus interval (NACTO 2016). | Use a combination of onboard and wayside technologies to determine what type of signal priority (green extension, red truncation, phase insertions, etc.) can be implemented (NACTO 2016). | Incorporate continuous detection along transit corridors, not just at intersection approaches. May be integrated with automatic passenger counters, communication among transit vehicles and signal controllers, and real-time traffic data to determine traffic signal priority (TSP) interventions with better precision and reduce general traffic impacts (NACTO 2016). |

| Variable Speed Limits | Deploy variable speed limits or advisories during peak periods. | Monitor and manage existing lanes with static speeds and manually change them based on incidents or other conditions. | Implement responsive variable speed limits or advisories based on current demand on a 24/7 basis. | Operate 24/7 automated variable speed limits or advisories using current/predicted levels of traffic, incidents, and weather. |

ATM Strategies

The following sections provide brief descriptions of the ATM strategies included in this guide. Additional detail about each strategy is included in Appendix B: ATM Strategy Fact Sheets. Material provided in the appendix includes the following specific details related to each ATM strategy:

- Strategy name and definition.

- Application scenarios.

- Application geography.

- Strategy variations.

- Supporting physical or technology elements.

- Time to implementation.

- Scale.

- Context.

- Support of priority/multimodal operations.

- Potential benefits.

- Cost considerations.

- Organizations and partners.

- Compatible ATM strategies.

- Implementation considerations.

- Illustration of the strategy.

These sections represent the overall view of the ATM strategies included in this guide, while other chapters include specific aspects and details of each strategy as they relate to specific topics.

Adaptive Ramp Metering

Adaptive ramp metering dynamically adjusts the rate at which traffic is allowed to enter a freeway facility based on current (or predicted) operating conditions of both the freeway and the ramps (FHWA 2023b). An adaptive ramp metering system balances freeway demands and queue growth over multiple ramps to maintain a smooth flow on the freeway for as long as possible, delaying the onset of congestion. Facilitating a more uniform rate of vehicles entering the traffic stream means that vehicles enter at a system-controlled rate rather than in large groups, which can create a bottleneck at the merge point of the main lane and the ramp and increase delay on both facilities. Agencies can utilize traffic detection systems and advanced control algorithms to change metering strategies as congestion builds and dissipates. Adaptive ramp metering strategies can also be coupled with dynamic bottleneck identification, automated incident detection, and adjacent arterial traffic signal operations to effectively optimize the performance of the systems during oversaturated conditions.

Figure 2-3 shows an example of adaptive ramp metering deployed along I-580 in San Francisco, California. The ramp signal controls the flow of vehicles on the ramp as they enter the mainline freeway lanes. A typical installation might involve detectors on the main lanes to monitor speeds and headways, along with queue detectors on the ramp to monitor the length of the ramp queue and minimize the occurrence of queue spill-back to adjacent arterials and intersections.

A strategy variation for adaptive ramp meters is the use of bypass lanes. With these lanes, agencies can allow a specific class of vehicle (usually a HOV, bus, or other dedicated vehicle) to avoid delay at ramp meters and have the right-of-way to merge directly onto the freeway (Mizuta et al. 2014). A typical scenario for a bypass lane would include a single detection loop that would incrementally increase the length of the ramp meter cycle each time a vehicle is detected.

From a safety perspective, ramp meters help break up platoons of vehicles that are entering the freeway and competing for the same limited gaps in traffic. Ramp metering facilitates smooth merging maneuvers, which reduces the likelihood of collisions on the freeways’ main lanes (Mizuta et al. 2014). Additionally, ramp metering helps with ramp queue management. This management helps prevent queues from spilling onto the adjacent arterial and clogging the city street network with stopped vehicles waiting to enter the freeway. First-time implementation of ramp meters in a metropolitan area generally requires outreach and public engagement. Through outreach efforts, agencies need to convey to the public the benefits of these traffic signals and familiarize drivers with signal operations and compliance strategies. Properly justified ramp metering installations have been shown to produce safety and other operational benefits (Kang 1999).

Adaptive Traffic Signal Control

Adaptive traffic signal control is a collection of dynamic traffic signal control strategies that agencies can deploy in response to actual (measured) or predicted travel conditions on individual arterials or a network of arterials. Adaptive traffic signal control also includes strategies such as traffic-responsive signal control and multimodal traffic signal control. Adaptive traffic signal control involves the continuous monitoring of arterial traffic conditions and queuing at intersections and the dynamic adjustment of signal timing plan parameters to optimize one or more operational objectives (e.g., minimize overall delays, balance queue growth, prevent queue spill-back, accommodate specific user types) based on measured travel conditions in the corridor (FHWA 2023b). The ATM approach takes advantage of technology to make a system of intersections as efficient as possible for the prevailing conditions. Adaptive traffic signal control is effective where daily variability in traffic demand results in unpredictable travel patterns that cannot be reasonably accommodated by updating coordinated signal timing parameters on a

frequency consistent with agency traffic signal operations objectives. Adaptive traffic signal control can be coordinated with adaptive ramp metering to cooperatively store demands at the intersection and on the ramp at freeway interchanges. Adaptive traffic signal controls rely heavily on traffic sensor systems to measure changes in normal travel patterns and advance control algorithms to dynamically alter traffic signal timing parameters (i.e., cycle, splits, and/or offsets) in response to measured conditions. Figure 2-4 illustrates an example of adaptive traffic signal control in action.

Traffic-responsive signal control involves developing signal timing plans that are implemented when certain conditions and/or performance thresholds are met. This strategy is similar to adaptive control because it is meant to be applied in real time according to real-time demands. If an agency does not have an adaptive system in place, it can offer more efficient operations using traffic-responsive signal control. Agencies frequently use traffic-responsive operations to deploy specialized signal timing plans for special events (Dowling and Elias 2013) or to implement coordinated timing plans for arterials that span multiple jurisdictions.

Multimodal traffic signal control is used to provide special treatment to preferential users (such as transit vehicles, light-rail vehicles, bicycles and pedestrians, and trucks) at signalized intersections. Agencies can provide preferential treatment by utilizing the priority features of a traffic signal controller. Under priority control, agencies work with the existing signal control plan to provide improved operations at the signal for special types of users without disrupting coordination and traffic progression (Dowling and Elias 2013). This strategy dynamically improves operations for preferential vehicles at the signal and facilitates the multimodal use of the intersection. Agencies frequently use this strategy to provide priority access to transit and light-rail vehicles by allowing them to jump queues at an intersection. Agencies that have implemented adaptive control have identified the need for (1) better local support from the vendor, (2) better in-house planning and institutional support, (3) better planning of the detection and communications infrastructure, and (4) a detailed preinstallation evaluation to estimate operational benefits (Stevanovic 2010).

Dynamic Junction Control

Dynamic junction control is the strategy of dynamically allocating lane access on mainline and ramp lanes in interchange areas where high traffic volumes are present and the relative

demand on the mainline and ramps changes throughout the day (FHWA 2023b). Using dynamic signs (and sometimes lighted pavement markings), mainline lanes can be closed or become exits, shoulders can be opened, and other strategies can be employed to accommodate entering or exiting traffic. The intent is to take advantage of available capacity on the mainline facility and adjacent ramps to provide dedicated access to the greater demand at the appropriate time when it is most needed.

Dynamic junction control can be effective in areas with significant merging volumes (more than 900 vehicles per hour), available capacity on general purpose lanes upstream of the interchange that can be borrowed without generating stop-and-go traffic after implementation, and traffic volumes that peak at different times on the general purpose lanes and merging lanes. It can be an effective bottleneck mitigation strategy for specific facilities.

Figure 2-5 and Figure 2-6 display the application and signing for this strategy as deployed on the northbound connector from SR-110 connector to northbound I-5 in Los Angeles, California.

The project involved opening the right shoulder on the connector ramp during the peak period to provide additional capacity, improve safety and mobility on the connector, and eliminate the occurrence of drivers traveling on the shoulder of the connector during peak periods. When the junction control is active and the ramp shoulder is open, the dynamic message sign (DMS) over the shoulder indicates that it is available for use as an exit lane (Figure 2-5), and a diagrammatic sign is illuminated over the second-from-the-inside main lane to indicate that it can be used as a through lane or for the left exit to I-5 (Figure 2-6).

A variation of dynamic junction control along arterials is dynamic turn restrictions. With this application, dynamic turn restrictions provide agencies with the opportunity to restrict right turns, left turns, and/or U-turns based on need rather than by time of day (Dowling and Elias 2013). This approach to adapting turns based on need helps improve safety and operations at the intersection without sacrificing capacity. Additionally, dynamic turn restrictions can accommodate transit to facilitate multimodal operations and are especially effective when an intersection is in the vicinity of a railroad grade crossing in improving efficiency when trains are present and/or preemption is active (Dowling and Elias 2013).

Dynamic Lane Reversal

The reversal of lanes to dynamically allocate the capacity of congested roads, thereby allowing capacity to better match traffic demand throughout the day, is the ATM strategy known as dynamic lane reversal (FHWA 2023b). Agencies can implement dynamic lane reversal on both freeways and arterial facilities. This strategy is most applicable on facilities with a directional imbalance of more than 65/35 with primary through traffic and predictable congestion patterns. It is also effective in emergencies to enable emergency personnel to respond to incidents on a facility with limited access.

A freeway application of dynamic lane reversal is shown in Figure 2-7 along I-30 in Dallas, Texas, east of the downtown area. In this installation, a movable barrier is used to provide a dedicated, barrier-separated HOV lane in the peak-period direction. The lane forms its own corridor within the freeway, and access is limited to a few selected points. Figure 2-8 shows an example of dynamic lane reversal on FM 157 (Collins Street), an arterial street in Arlington, Texas. In this location, the direction and use (e.g., through and/or turns) of the center three lanes along the arterial are changed depending on the demand.

A distinction in terms of use exists on a freeway versus an arterial. Typical lane reversal strategies on freeways include increasing capacity in a peak direction, providing for emergency operations (contraflow lanes), or incorporating lanes as part of a managed lanes facility, such as an HOT/HOV lane. On arterials, lane reversals account for directional traffic flows. While a variety of planned time-of-day lane reversals are available, most applications do not change dynamically. However, the ability to reverse lanes might be an important element of traffic management response during emergencies. Arterial applications of reversible lanes may face criticism from business owners and others because these configurations might require left-turn restrictions or parking removal. Existing facilities are generally accepted and understood by the traveling public but may confuse the unfamiliar traveler due to their relatively low level of use, especially on arterials. Additional information related to reversible lanes used as a managed lane application is provided in NCHRP Research Report 835: Guidelines for Implementing Managed Lanes (Fitzpatrick et al. 2016).

Dynamic Lane-Use Control

The ATM concept of dynamic lane-use control involves dynamically closing or opening individual traffic lanes as warranted and providing advance warning of closures (typically through dynamic lane control signs) to safely merge traffic into adjoining lanes (FHWA 2023b). The goal of this strategy is to direct traffic into appropriate lanes based on conditions. This ATM strategy can be used by agencies to meet variable demand, or it can be used in areas experiencing heavy congestion caused by incidents or special events. Dynamic lane-use control works by allowing agencies to change lane assignments to meet different traffic demands. In arterial applications, for example, an approach with heavy left-turn movements in the morning peak can operate with dual left-turn lanes during that peak period but can allow a through movement in the second left-turn lane once the left-turn demand has abated (Dowling and Elias 2013). Figure 2-9 shows an example of dynamic lane-use control on I-15 in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Compliance with lane control signage depends on various factors including traffic flow, the presence of an incident or emergency vehicle, and supporting signage. Broadly, however, human factor analysis of lane-use signage indicates that travelers understand the sign indications. During placement, agencies can consider special geometric characteristics and driver decision points, including consideration of line-of-sight impacts, in the placement of lane control signs. They also need to ensure that lane control signage options (i.e., text, symbols) comply with the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) (FHWA 2022).

Part-Time Shoulder Use

Part-time shoulder use involves offering the use of the shoulder as a travel lane(s) based on recurring congestion levels during peak periods and in response to incidents or other conditions as warranted during both peak and nonpeak periods (FHWA 2023b). Typical applications for part-time shoulder use are for managed lanes (for transit vehicles or HOV only) or for all vehicles. Both applications offer to potentially improve travel time and trip reliability for users. Figure 2-10 shows an example of part-time shoulder use in Columbus, Ohio, known as the I-670 SmartLane. In 2019, the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) opened the SmartLane to allow an extra lane of travel on upgraded highway shoulders during peak congestion or to aid in incident management efforts (ODOT 2023). Opening the shoulder has reduced the average travel time from 20 minutes to 5 minutes and improved the reliability on the facility with more consistent and overall higher speeds.

Public concerns regarding the safety of the lanes need to be addressed as part of the deployment. Depending on the location, the public might be concerned that the use of shoulder lanes for general traffic will make the traffic conditions worse by attracting more traffic to the facility. Typically, part-time shoulder use is implemented to increase capacity when congestion builds and when speeds are reduced. Thus, the combination of reduced congestion via higher capacity

and lower speeds reduces both the likelihood and severity of crashes. Noise concerns also need to be addressed. With existing peak-period shoulder use, agencies have generally been satisfied with the safety performance of the facility. Law enforcement should also be engaged early in the planning process and pushed toward being champions of shoulder use for travel.

Queue Warning

Queue warning involves the real-time display of warning messages along a roadway (typically on a DMS and possibly coupled with flashing lights) to alert motorists that queues or significant slowdowns are ahead, thus reducing rear-end crashes and improving safety (FHWA 2023b). Figure 2-11 shows an example of a queue warning system in operation at the beginning of a major work zone on I-35 in Waco, Texas.

To be effective, queue warning systems should be installed in consideration of rapidly fluctuating queues. Warning signs or devices placed too close to the queue tails might be overrun, with the possibility of drivers encountering the queue before they see the sign. Warning signs placed too far from the queue, if the downstream location of the queue is given, can become inaccurate between the time drivers view the sign and encounter the queue. Because conditions change too quickly for human operators to handle appropriate warning sign adjustments, an automated system for real-time adjustments to locate queues is optimal. Locating queues, for which drivers are advised of the distance to the queue tail, will require multiple detection stations, as well as multiple advance warning sign locations.

Transit Signal Priority

Transit signal priority (TSP) involves the management of traffic signals to improve the efficiency and reliability of bus operations. Passive priority strategies do not require vehicle detection technology. Rather, they involve the use of area-wide traffic signal timing plans that favor transit-heavy corridors and/or that match the average bus speed along the corridor rather than the average vehicle speed (FHWA, forthcoming). With active priority, transit vehicles are detected near a signal-controlled intersection using a variety of technologies, and the system allows the bus to pass through more quickly by turning the traffic signals to green sooner or extending the green phase. Fully adaptive systems can change a signal timing plan based on

real-time conditions, such as bus occupancy, traffic volume, or bus schedule adherence (FHWA, forthcoming). Figure 2-12 illustrates a congested transit corridor that can accommodate TSP for improved transit vehicle operations.

Variable Speed Limits

Variable speed limits (VSLs) involve the adjustment of speed limits based on real-time traffic, roadway, and/or weather conditions (FHWA 2023b). They can either be enforceable (regulatory) speed limits or recommended speed advisories, and they can be applied to an entire roadway segment or individual lanes. VSLs are also known as dynamic speed limits, variable advisory speeds, and speed harmonization. Figure 2-13 shows an example of VSLs deployed in Seattle, Washington. In this application, the Washington State DOT (WSDOT) installed ATM strategies on I-5, SR-520, and I-90 that included dynamic lane-use control, DMSs, and enforceable VSL

signage to alert drivers of delays and to direct drivers out of incident-blocked lanes (Schroeder et al. 2014). As shown in the photograph, the left lane has a higher speed limit. This lane was already designated as an HOV lane prior to the ATM installation, so the higher speed limit provides an added benefit to those HOV users in the lane when the VSL is active. The installations on SR-520 and I-90 were part of the FHWA Urban Partnership Agreement (UPA) project.

A specific outreach strategy should be in place to enable a clear understanding of the concept of VSLs by travelers. In the absence of an outreach strategy, implementations are prone to resistance and negative feedback from travelers. Agencies like the Utah DOT (UDOT) have publicized their VSL implementations widely in local media. The distinction between enforceable and advisory speed limits is blurred by the enforcement approach. Typically, law enforcement personnel ticket drivers for driving too fast for the conditions rather than speeding when VSLs are in place. Having buy-in from local law enforcement can help agencies make the case for the benefits of VSL. Additionally, a sustained media campaign on the role of the signs is beneficial to overall success and compliance. The specific impacts of VSL in U.S. deployments have been mixed. A comprehensive analysis of VSL and advisories studies (simulations, implementation and field testing, and VSL with ramp metering) showed a significant improvement in safety but mixed results on traffic flow (Lu and Shladover 2014).

ATM Successes

Various infrastructure owner-operators across the United States and globally have deployed ATM strategies to achieve safety and operational benefits in their jurisdictions. The following sections highlight key impacts of these strategies that illustrate successes and the potential benefits of ATM. Appendix C provides detailed case studies that further describe specific ATM applications and the impacts of those deployments on their corresponding facilities and networks, both freeways and arterials. The case studies include the following:

- I-35 end-of-queue warning, Texas.

- US-23 Flex Route, Michigan.

- Dynamic lane arterial assignment, California.

- I-670 SmartLane, Ohio.

- Project Neon, US-15, Nevada.

- ATM on OR-217, Oregon.

Domestic Applications

The deployment of ATM projects in the United States has grown in popularity, and the level of operations across these projects varies across the active management continuum. Some deployments involve time-of-day applications while others represent truly dynamic operations. Overall, the more predominant ATM strategies deployed to date in the United States are adaptive ramp metering, adaptive traffic signal control, VSLs, and dynamic lane-use control. Experience has been positive overall, and these strategies demonstrate that reductions in congestion and improvements in travel time reliability can be achieved. Additionally, some of these strategies are deployed in work zone applications to improve operations impacted by construction.

Domestically, the use of adaptive ramp metering has shown both safety and mobility benefits when compared with no ramp metering, including drops in collisions in Portland, Oregon (43 percent—peak period); Seattle, Washington (39 percent—overall); Minneapolis, Minnesota (24 percent—peak period); and Long Island, New York (15 percent—overall) (Chajka-Cadin et al. 2021b). Average travel speeds and travel times have also improved in these regions.

Adaptive traffic signal control has reduced stops at traffic signals (10 to 41 percent) and reduced delays (5 to 42 percent) across the country, depending on the location and application (Chajka-Cadin et al. 2021a). Additionally, system operators have found that using adaptive traffic signal control delays the onset of oversaturation and reduces the duration of delay times (Stevanovic 2010).

The use of TSP has shown benefits in various locations around the country. Examples include a reduction in signal delay (40 percent) in Tacoma, Washington, by deploying transit signal priority and signal optimization; an improvement in transit travel time (10 percent) and transit travel time reliability (19 percent) in Portland, Oregon; a reduction in bus travel times (25 percent) in Los Angeles, California; and a reduction in the average running time for transit vehicles (15 percent) in Chicago, Illinois (Chajka-Cadin 2021b).

The VSLs and dynamic lane assignments deployed in Seattle, Washington, along I-5, reduced total crashes by 11 percent along the facility (Schroeder et al. 2014). In Minneapolis, Minnesota, intelligent lane control signals (ILCSs) and a priced dynamic shoulder lane were implemented along with other regional strategies. No negative impacts on safety resulted from the projects. Law enforcement and first responders indicated that the ILCSs helped slow traffic and move it out of blocked lanes during incident response. Anecdotally, they perceive that the signs help their ability to respond to crashes and maintain traffic flow during incidents (Turnbull et al. 2013).

Global Experiences

A 2007 international scan report first highlighted the potential for ATM to address challenges faced by transportation agencies in the United States (Mirshahi et al. 2007). The report reviewed European best practices and identified commonalities in challenges and issues in Europe and the United States. The challenges included an increase in travel demand, growth in congestion, commitment to safety, execution of a shift in agency culture toward active management and system operations that focus on the customer, and a willingness to use innovative strategies to address congestion, as well as the reality of limited resources to address all these challenges (Mirshahi et al. 2007). The following sections provide some examples of ATM deployments overseas. Though not exhaustive, the examples show the diversity of ATM strategies being used overseas from which the United States adapted the strategies included in this guide.

Adaptive Ramp Metering

Ramp metering was first implemented in the Netherlands in 1989 to relieve motorway congestion, improve merging behavior, and discourage drivers from exiting the facility for a short distance to avoid congestion on the motorway (Middelham 2006). Figure 2-14 shows a typical installation for a two-lane ramp, which includes two signal heads on an overhead gantry and ground-mounted signal heads that face the driver at the stop bar on each side of the ramp. Each installation provides a bypass lane for emergency vehicles and buses, and the typical length of a slip-ramp with metering is 300 m. Many ramps use photo enforcement cameras to record violations.

Adaptive Traffic Signal Control

The practice of adaptive signal control has been common overseas for numerous years. It evolved as a response to the challenge of developing traffic-responsive signal operations within the context of rapidly changing traffic patterns and demand (Stevanovic 2010). Examples of adaptive signal control systems that both originated overseas and represent evolutions and improvements on those systems include the following: Sydney Coordinated Adaptive Traffic System (SCATS), Split Cycle Offset Optimization Technique (SCOOT), Optimization Policies

for Adaptive Control (OPAC), Programming Dynamic (PRODYN), System for Priority and Optimisation of Traffic (SPOT), Urban Traffic Optimisation by Integrated Automation (UTOPIA), and Real-Time Hierarchical Optimized Distributed and Effective System (RHODES).

Dynamic Shoulder Use/Dynamic Lane-Use Control

In England, the Highways Agency (now Highways England) implemented shoulder use on M42 as part of a pilot project for multiple traffic management measures that included speed harmonization with camera enforcement, incident detection with queue warning, and traveler information (Grant 2006). In the pilot project, dynamic shoulder use was controlled by the TMC and was exclusively applied between exits, making the shoulder operate like an auxiliary weaving lane. Enforcement was performed through a wide network of cameras with automatic numberplate recognition.

Overhead lane control signals were used to implement temporary shoulder use. When the shoulder was meant for emergency purposes only, a red cross was shown in the sign above the shoulder, while the other overhead signs were either blank (under normal conditions) or displayed a mandatory speed limit (under congested or incident conditions) (Mirshahi et al. 2006). When the shoulder was open to traffic, the mandatory speed limit was displayed on the shoulder overhead sign and a description of the situation was written on a DMS (typically written as “congestion, use hard shoulder”) as pictured in Figure 2-15. These lane control signals could also prove very useful during incidents to clear one lane and provide quicker access for emergency vehicles. The pilot project included other features that were added to the motorway, including lighting and emergency phones at every emergency refuge area.

Queue Warning

Figure 2-16 is an example of a queue warning installation in Germany (Pilz 2006). This application uses dynamic traffic detection to activate warning signs and flashing lights. This strategy allows the traveler to anticipate a situation requiring emergency braking and limits the extent of speed differentials, erratic behavior, and queuing-related collisions. The pictogram warning can be turned on manually by a TMC operator or automatically when it is integrated into an incident management program (Mirshahi et al. 2006).

Variable Speed Limits

The Road Directorate of the Danish Ministry of Transport and Energy decided to deploy VSLs as part of their work zone traffic management strategies for the multiyear widening of the M3 (see Figure 2-17). Using traffic detection systems, closed-circuit television cameras (CCTVs), and DMSs, control center staff in the region monitored traffic and reduced speeds when congestion began to build. This active management strategy was deemed a success by the Road Directorate and project staff. As a result, incidents on the motorway did not increase during the reconstruction project, while the existing two lanes were maintained at narrower-than-normal widths and no entrance ramps, exit ramps, or bridges were closed (Middelham 2006).

Smart Motorways—Australia

The concept of smart motorways (also known as managed motorways and smart freeways) has been applied across Australia for several years. Smart motorways describe facilities that have information, communications, and control systems incorporated in and alongside the roadway that actively manage traffic flows and improve road capacity and safety, as well as deliver other important outcomes for road users, such as better travel reliability and real-time traveler information (Austroads 2016). The focus of smart motorways is to use technology to optimize the performance of the road infrastructure, facilitate a more productive and sustainable transport network, and meet road user and community needs. The technologies included in smart motorways include but are not limited to the following (Queensland Government 2023; Austroads 2016):

- VSLs.

- Dynamic lane-use control or flexible lane control.

- Adaptive and/or coordinated ramp metering.

- Adaptive traffic signal control.

- Arterial road and motorway interface management.

- Provision of an emergency lane.

- DMSs with travel time and real-time traveler information.

- Roadside data systems and sensors.

The traffic management system that forms the backbone of the smart motorways initiative integrates real-time conditions into algorithms that predict traffic congestion and proactively respond to conditions. Enhanced emergency services also improve incident response to improve safety. An analysis of a deployment in Victoria on the M1 motorway in Melbourne demonstrated that the system increased traffic flow by 5 to 8 percent, improved traffic speeds by 35 to 59 percent, and improved overall travel-time reliability by 150 to 500 percent during peak periods. In addition, the 5-year-average crash rate on the M1 motorway was shown to decline 31 percent before and after project completion (from 9.15 to 6.31 crashes per 100 million vehicle kilometers traveled) (Vong and Gaffney 2012). Overall, smart motorways can increase capacity 5 to 22 percent, improve throughput 1 to 20 percent, and improve reliability 4 to 60 percent, depending on the location and deployed technologies (Austroads 2016).

Smart Motorways—United Kingdom

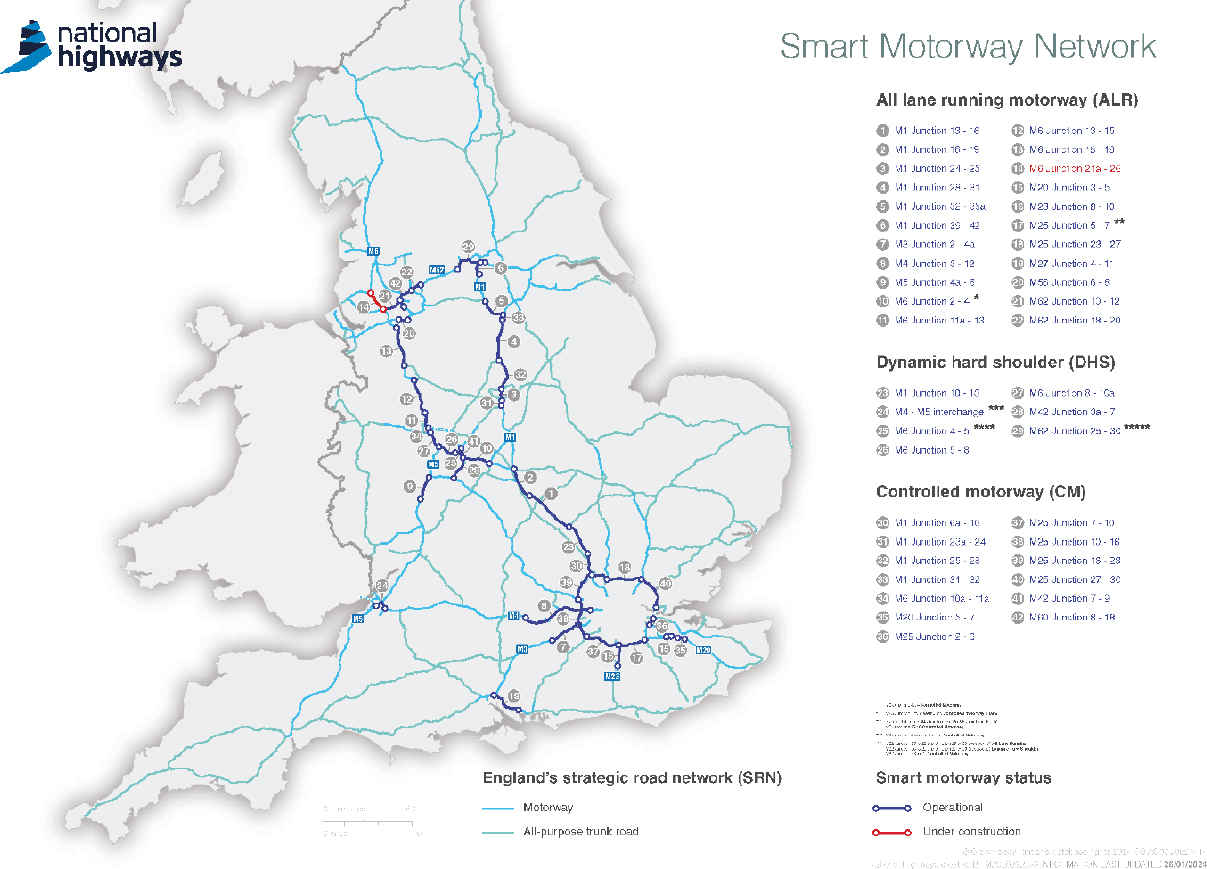

Highways England (formerly Highways Agency) in the United Kingdom has advanced the concept of smart motorways, which is an evolution of previous ATM applications. This concept involves a variety of applications including a controlled motorway, hard-shoulder running, and all-lane running (ALR)—all of which utilize technology for the purpose of improving journeys and helping ease congestion (National Highways 2023). Figure 2-18 illustrates the current plan for smart motorways in the United Kingdom. An overarching safety assessment of nine smart motorway ALR deployments found that the safety performance of ALR showed a statistically significant improvement in crashes resulting in injury or fatalities (Highways England 2019). An independent review of the ALR concept (Simpson 2021) and a related quality assurance assessment of the ALR motorway safety data (Office of Rail and Road 2021) provided conflicting results as to the safety benefits of ALR. Currently, the broad expansion of ALR roads is on hold until 5 years of data are available for a thorough safety and operational analysis.

General Observations

The European approach to congestion management programs, policies, and experiences has helped inform transportation professionals in the United States in their related activities. Notable observations include the following:

- Active management is essential to the European approach to congestion management, building on advancements in technology and traffic management experience to make the best use of existing capacity and provide additional capacity during periods of congestion or incidents.

- The European mobility policy has the traveler as a focal point, and congestion management strategies center on the need to ensure travel time reliability for all trips, regardless of the time of day.

- Transportation and traffic management operations are priorities in the planning, programming, and funding processes and are seen as critical needs to realize the benefits of investment in the transportation infrastructure and deployed systems for congestion management.

- European agencies use tools to support cost-effective investment decisions at the project level to ensure that implemented strategies have the best benefit-cost ratio and represent the best investment of limited resources, including sketch planning and modeling tools that facilitate sustainable traffic management by quantifying the benefits of traffic management strategies.

- European agencies recognize that it is essential to provide consistent messages to roadway users to reduce the impact of congestion on those travelers.

- European agencies typically include automated enforcement tools when implementing ATM strategies; such tools are not commonly used in the United States.

Final Remarks

The lessons learned by transportation agencies related to ATM applications around the world are varied and cover a multitude of issues related to the operational approach (Jones et al. 2011; Kuhn et al. 2013). For example, ATM requires that agencies focus on improving the driver (or customer) experience in traffic. Effective engagement at every stage of project planning, development, and implementation is essential to implementing ATM on a broad basis. Transparent information about the project; its likely effects; its benefits; and consistent messages from all levels of the organization as the project is discussed with decision-makers, partners, and the public are essential to selling the concept, especially when the project resonates with the greater

population by addressing broader issues such as health and safety (Kuhn et al. 2013). As a part of that focus, educating customers and policymakers about the benefits of ATM is important to enlist support for these strategies being funded, either as part of construction projects or as tailored ATM projects. The agency must also be willing to change project parameters in response to public comments.

Once a project is operating, real-time, accurate communication gives travelers actionable information that improves their ability to make better decisions about their travel routes and times. Furthermore, technological capability is only one of the essential factors to ATM success; other important elements exist for managing the transportation system. ATM approaches may require changes in some policies and regulations, additional information on such will be provided elsewhere in this guide. ATM often pushes the boundaries of operations, partnerships, and opportunities. Ensuring that laws are flexible enough to accommodate them and the myriad ways these strategies are planned, developed, financed, and implemented helps move the state of the practice forward (Kuhn et al. 2013).

Chapter 2 References

Austroads. (2016). Guide to Smart Motorways. Austroads, Ltd. Publication AGSM-16. https://austroads.com.au/network-operations/network-management/guide-to-smart-motorways. Accessed October 2023.

Chajka-Cadin, L., M. Petrella, S. Plotnick, and C. Roycroft. (2021a). Intelligent Transportation Systems Deployment Tracking Survey: 2020 Arterial Findings. U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-JPO-21-892. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/60579. Accessed April 2023.

Chajka-Cadin, L., M. Petrella, S. Plotnick, and C. Roycroft. (2021b). Intelligent Transportation Systems Deployment Tracking Survey: 2020 Freeway Findings. U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-JPO-21-891. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/60122. Accessed April 2023.

Dowling, R., and A. Elias. (2013). NCHRP Synthesis 447: Active Traffic Management for Arterials. Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, Washington, DC. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/22537/active-traffic-management-for-arterials. Accessed April 2023.

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). (2012). ATDM Program Brief: Active Traffic Management. U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-HOP-13-003. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop13003/fhwahop13003.pdf. Accessed April 2023.

FHWA. (2022). Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, 2009 Edition. U.S. Department of Transportation. https://mutcd.fhwa.dot.gov/pdfs/2009r1r2r3/pdf_index.htm. Accessed April 2023.

FHWA. (2023a). “Active Traffic Management.” U.S. Department of Transportation. http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/atdm/approaches/atm.htm. Accessed April 2023.

FHWA. (2023b). “Active Transportation and Demand Management.” U.S. Department of Transportation. http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/atdm/index.htm. Accessed April 2023.

FHWA. (2023c). Active Management Cycle Guide. U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-HOP-19-013.

FHWA. (Forthcoming). TSMO Strategy Toolkit—Getting Started: Tips and Frequently Asked Questions. U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-HOP-23-XXX.

Fitzpatrick, K., M. Brewer, S. Chrysler, N. Wood, B. Kuhn, G. Goodin, C. Fuhs, D. Ungemah, B. Perez, V. Dewey, N. Thompson, C. Swenson, D. Henderson, and H. Levinson. (2016). NCHRP Research Report 835: Guidelines for Implementing Managed Lanes. Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/23660/guidelines-for-implementing-managed-lanes. Accessed April 2023.

Grant, D. (2006). “M42 Active Traffic Management Pilot Project,” Highways Agency, Department for Transport. Presentation to Planning for Congestion Management Scan Team, London, England.

Highways England. (2019). Smart Motorway All Lane Running Overarching Safety Report 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5e6a216486650c727d932af6/SMALR_Overarching_Safety_Report_2019_v1.0.pdf. Accessed October 2023.

Jones, J., M. Knopp, K. Fitzpatrick, M. Doctor, C. Howard, G. Laragan, J. Rosenow, B. Struve, B. Thrasher, and E. Young. (2011). Freeway Geometric Design for Active Traffic Management in Europe. Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-PL-11-004. https://international.fhwa.dot.gov/pubs/pl11004/pl11004.pdf. Accessed April 2023.

Kang, S. (1999). Assessing the Benefits and Costs of Intelligent Transportation Systems: Ramp Meters. In PATH ITS Research Digests, T. Chira-Chival, ed. University of California, Berkley, Institute of Transportation Studies, Technology Transfer. Publication UCB-ITS-PRR-99-19. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7cs397t4.

Kuhn, B., D. Gopalakrishna, and E. Schreffler. (2013). The Active Transportation and Demand Management (ATDM) Program: Lessons Learned. Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-HOP-13-018. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop13018/fhwahop13018.pdf. Accessed April 2023.

Lu, X., and S. Shladover. (2014). “Review of Variable Speed Limits and Advisories.” Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, No. 2423, p. 15–23.

Middelham, F. (2006). “Dynamic Traffic Management.” AVV Transport Research Centre, Ministry of Transport, Public Works, and Water Management. Presentation to Planning for Congestion Management Scan Team, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Mirshahi, M., J. Obenberger, C. Fuhs, C. Howard, R. Krammes, B. Kuhn, R. Mayhew, M. Moore, K. Sahebjam, C. Stone, and J. Yung. (2007). Active Traffic Management: The Next Step in Congestion Management. Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-PL-07-012. https://international.fhwa.dot.gov/pubs/pl07012/atm_eu07.pdf. Accessed April 2023.

Mizuta, A., K. Roberts, L. Jacobsen, and N. Thompson. (2014). Ramp Metering: A Proven, Cost-Effective Operational Strategy—A Primer. Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-HOP-14-020. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop14020/fhwahop14020.pdf. Accessed April 2023.

NACTO (National Association of City Transportation Officials). (2016). Transit Street Design Guide. https://nacto.org/publication/transit-street-design-guide/. Accessed October 2023.

National Highways. (2023). “Smart Motorways Evidence Stocktake.” https://nationalhighways.co.uk/our-work/smart-motorways-evidence-stocktake/. Accessed April 2023.

ODOT (Ohio Department of Transportation). (2023). TSMO Project: I-670 Smart Lane (Columbus). https://www.transportation.ohio.gov/wps/wcm/connect/gov/3e2fefcc-21a8-4732-904b-a69d0b616d93/TSMO_CaseStudy_I-670SmartLane.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CONVERT_TO=url&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE.Z18_M1HGGIK0N0JO00QO9DDDDM3000-3e2fefcc-21a8-4732-904b-a69d0b616d93-n2XfjHN. Accessed October 2023.

Office of Rail and Road. (2021). Quality Assurance of All Lane Running Motorway Data. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1015501/orr-quality-assurance-of-all-lane-running-motorway-data.pdf. Accessed October 2023.

Pilz, A. (2006). “Presentation of the Traffic Centre Hessen.” Hessian Ministry of Economy and Transport. Presentation to Planning for Congestion Management Scan Team, Frankfurt, Germany.

Queensland Government. (2023). “Smart Motorways.” https://www.tmr.qld.gov.au/Travel-and-transport/Road-and-traffic-info/Smart-Motorways. Accessed April 2023.

Schroeder, J., T. Smith, K. Turnbull, K. Balke, M. Burris, P. Songchtritksa, B. Pessaro, E. Saunoi-Sandgren, E. Schreffler, and B. Joy. (2014). Seattle/Lake Washington Corridor Urban Partnership Agreement: National Evaluation Report. Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-JPO-14-127. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/3496. Accessed April 2023.

Simpson, S. (2021). Independent Review of All Lane Running Motorways in England. Royal Haskoningh DHV UK Ltd. https://www.royalhaskoningdhv.com/-/media/images/newsroom/news/2021/our-report-into-driver-safety-on-all-lane-running-motorways-download.pdf. Accessed October 2023.

Stevanovic, A. (2010). NCHRP Synthesis 403: Adaptive Traffic Control Systems: Domestic and Foreign State Practice. Transportation Research Board of the National Academies, Washington, DC. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/14364/adaptive-traffic-control-systems-domestic-and-foreign-state-of-practice. Accessed April 2023.

Turnbull, K., K. Balke, M. Burris, P. Songchitruksa, E. Park, B. Pessaro, J. Samus, E. Saunoi-Sandgren, D. Gopalakrishna, J. Schroeder, C. Zimmerman, E. Schreffler, and B. Joy. (2013). Minnesota Urban Partnership Agreement: National Evaluation Report. U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-JPO-13-048.

Vong, V., and J. Gaffney. (2012). Monash-Citylink-West Gate Upgrade Project: Implementing Traffic Management Tools to Mitigate Freeway Congestion. VicRoads.