Active Traffic Management Strategies: A Planning and Evaluation Guide (2024)

Chapter: 8 ATM Implementation and Deployment

CHAPTER 8

ATM Implementation and Deployment

Chapter Highlights and Objectives

The implementation stage of an active traffic management (ATM) deployment results from the culmination of a coordinated systems planning and design effort. ATM requires consideration of construction challenges in the context of an overcapacity facility. Additional complexities often exist when developing new software to operate ATM strategies, acquiring technology infrastructure, and coordinating implementation across civil and software components. The delivery method for implementing the project may also introduce additional requirements that make an ATM project different from a typical ITS construction project. Effective coordination and collaboration at every stage of construction and deployment become key to successful ATM implementation.

This chapter presents the key activities that will occur in a typical ATM implementation and deployment phase. These activities include:

- Project Delivery Considerations. Discusses different project delivery methods, such as design-build, design-bid-build, P3s, and other construction delivery models.

- Procurement and Scheduling. Identifies potential challenges with planning for procurement, including lead times and sequencing.

- Stakeholder Coordination. Presents the range of stakeholder perspectives and groups that should be included, particularly contractors, and discusses challenges coordinating complex ATM construction across multiple groups.

- Software Development and Implementation. Discusses software development processes, delivery models, and resources to support ATM software development.

- Construction. Identifies key construction scheduling considerations, including schedule management and risk monitoring.

- Pilot Operations and Rollout. Highlights successful practices from agencies that have piloted initial ATM implementations and adjusted strategies based on early operations performance.

- Public Outreach and Awareness. Lists strategies for successful public education campaigns on new ATM deployments, as well as ongoing education and outreach.

- Final Remarks. Summarizes the factors to consider for successful deployment and implementation of ATM.

- Chapter 8 References. Lists all references cited within the chapter.

Project Delivery Considerations

Construction and implementation for ATM can involve building and installing specific ATM components on an established facility, such as a freeway or arterial, or implementing ATM elements as part of a larger construction or facility expansion/rehabilitation effort. In the latter

scenario, where the ATM components are integrated into a larger civil engineering construction package, agency staff responsible for the ATM elements may need to play a larger role as part of the overall construction coordination and project management effort to help align technology infrastructure procurement, systems procurement, and system testing and integration activities within the broader project schedule (Kuhn et al. 2017).

An additional consideration for project delivery includes introducing ATM to existing reconstruction or maintenance projects. The following ATM applications could be used as tools to support traffic management during construction:

- Queue warning systems.

- VSLs in and near work zones.

- Lane control in response to restrictions on other travel lanes.

- Flexible use of the shoulder when other travel lanes are restricted.

ATM strategies and devices implemented could then remain after the reconstruction or maintenance project has been completed and transition to full-time, day-to-day operational use.

Agencies are continuing to adopt alternative project delivery approaches for construction in general; ATM can also be implemented using a variety of delivery methods. Delivery strategies, such as design-build and design-bid-build, are common for roadway construction and projects focused on technology implementation for traffic management. Agencies may also be looking at alternative financing and funding methods, such as P3s or concessionaire models for larger-scale implementations. Many state DOTs have procurement manuals and guidelines for various alternative delivery approaches; these guidance documents are best consulted early in the planning process.

Table 8-1 provides examples of different project delivery methods that could be used for ATM projects (Kuhn et al. 2017). Information has been updated to include example deployments. Following this table are additional considerations and context for several of the delivery methods typically used by agencies for ATM construction and implementation.

Design-Build Additional Considerations

In a design-build (DB) context, the DB solution provider will likely participate earlier in the project development, prior to design. Depending on the scope of services defined, the role of the DB team can range from supporting to leading any of the individual elements of project development. While most of the stakeholder coordination—such as engaging local partnering agencies or agencies supporting enforcement or incident response (law enforcement, emergency medical services, fire, or towing and recovery services)—would typically be handled by the owning agency, in a DB approach, the DB team may play a larger role than traditional contractors.

In both a DB and a design-build-bid (DBB) context, the scope or level of responsibility for stakeholder coordination and outreach for the contractor or DB team must be clearly identified within the procurement documents and deliverables.

Possible deliverables to define within the scope include the development of meeting agendas and summaries, education and outreach documentation, and coordination and communication protocols as well as participation in standing regional or partner agency coordination committees.

Another option in the DB realm is a design-build-operate-maintain (DBOM) solution where the scope would include operations and maintenance responsibilities in addition to design and construction. The DBOM team—typically a large and diverse team to address the full project life cycle of design through operations—would be involved in post-design needs, including the development of SOPs and the integration of maintenance activities for ATM components in

Table 8-1. Alternate project delivery methods.

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design-Build |

|

|

Washington (system minus gantries); Nevada I-15; Colorado US-36 Express Lanes (Phase 1). |

| Design-Bid-Build |

|

|

Washington (gantry only); Minnesota. |

| Construction Management at Risk (CMAR) |

|

|

No example included. |

| P3 |

|

|

Colorado US-36 Express Lanes (Phase 2); Europe (Denmark, England, Germany). |

SOURCE: Kuhn et al. 2017.

coordination with current ITS and roadway operations and maintenance. The DBOM team would also need to provide the staff to support operations and maintenance of the finished system.

Concessionaire Model

While DB and DBOM represent options for project delivery, the agency remains the ultimate owner of the facility (as with the traditional design-bid-build approach). Agencies may opt to pursue a concessionaire model, where a third-party concessionaire typically operates the facility under a long-term lease; this type of arrangement is often seen in toll-based operations that have ATM components. In such an arrangement, the concessionaire takes on many of the operating responsibilities (and liabilities) as the owner, such as a larger public outreach and marketing role, especially if there is the option of revenue generation through toll collection as a component of the facility. Additionally, the concessionaire becomes responsible for establishing formal memoranda of understanding between local transportation agencies and local law enforcement and public safety agencies. Operations, enforcement, incident response, and maintenance are all provided through the concessionaire, which could translate to multiple contracted arrangements to various providers.

To support the success of the corridor implementation, the relationship between the concessionaire and the ultimate end owner must be well codified in the concessionaire agreement. Additionally, the relationship between the two must be cultivated during the design and build phases of the project to prepare for operations on day one. The agreement should include conditions that mitigate the likelihood of the concessionaire operating with certain financial motives (e.g., to generate revenue sufficient to finance borrowing costs and/or to generate an operating profit).

Procurement and Scheduling

Contrary to typical civil projects or isolated ITS projects, ATM projects can involve a complex combination of materials, such as physical roadway construction materials, lighting, field equipment, gantries, and central software and operating systems. For certain technology field components, such as over-lane DMSs or VSL signs, time to acquire the components should be viewed as critical-path items. Additional schedule considerations include protocols and processes to support software development, testing, and training, which are critical and should be programmed in advance of the field element quantities. Components that must be tested with legacy platforms or platforms being developed by others outside of the ATM also should be ordered in advance to provide a structured testing process.

Lead time and sequencing are critical concerns for overhead sign mounting structures. Given that many construction methods for these types of units may require a complete road closure, it is important that the structures are made available as defined by the project schedule. Also, it is important that a strong inspection regime be in place to confirm the specifications necessary for an ATM structure. While overhead sign structures are relatively standard roadway components, gantries for an ATM environment may have cable access points, internal cable raceways, or special mounting bracket accommodations that differ from standard structures.

As an example of lead time and sequencing challenges, the I-80 Integrated Corridor Mobility project in the San Francisco Bay Area of California was a multiyear effort to plan, design, implement, and test a range of ATM technologies on a 20-mi segment of heavily traveled urban freeway. The project included LCSs, adaptive ramp metering, VSLs, software, and additional ITS infrastructure. Improvements were being implemented on the freeway and supporting arterial networks. The project was on an accelerated timeline to meet funding requirements. When technology was procured and acquired for the arterial systems, delays with construction on other project elements on the freeway meant the warranty periods for the equipment were at risk. Testing for the various software components was on different schedules and coordinating testing among the different freeway components and arterial components required careful attention to scheduling.

The inspection regime for an ATM project is similar to the inspection regime for any other ITS project. The inspection regime should be continuous throughout the project and include factory and preinstallation/construction-level, subcomponent-level, component-level, subsystem-level, and system-level inspection and testing. This regime applies to both technology items, such as signs and communications, as well as nontechnology items, such as conduits and foundations. Procurement documents should clearly specify testing expectations prior to technology delivery. A strong inspection regime requires that thorough documentation be submitted and approved throughout the project, as opposed to a single submittal at the end.

Agencies may require equipment availability during construction to maintain detection or video monitoring capabilities and/or post messages on DMSs and LCSs. These continued operations require careful coordination so that communication to this equipment is not disrupted

(Source: KHA).

during construction or during any equipment relocations. In some instances, agencies may require contractors to provide backup capabilities for monitoring and equipment control while ITS infrastructure is being installed or relocated. Figure 8-1 illustrates the complex equipment that is frequently installed as part of ATM projects.

A strong inspection regime also includes a rigorous evaluation of the built and under-construction project elements compared to the project specifications and requirements. In addition, the inspection regime maintains a level of distance between the construction/implementing team and the inspection team. These entities can be members of the same company, but the inspection regime should be an integrated component of the overall quality assurance/quality control process that provides a fresh set of eyes on the work.

Stakeholder Coordination

Implementing ATM strategies will require involvement from several different stakeholders, including those stakeholders internal to the agency, and, depending on the strategy, external to the owning agency. Chapter 3 identified collaboration as a key enabler for successful ATM, including involving appropriate stakeholders in the early planning and concept development stages. The types and levels of engagement of various stakeholders will be determined by the ATM strategy being implemented. The project delivery strategies presented earlier in this chapter may also lead to additional stakeholder involvement, such as agency legal representatives and procurement and administration staff among others.

Stakeholder Involvement and Representatives

Many of the stakeholders involved during the planning and design phases will remain integral during the implementation phase (Kuhn et al. 2013). It is expected that representatives from the owner agency’s ITS engineering, operations, and maintenance departments will maintain the same level of involvement and commitment during implementation as was demonstrated in the design stage. It also is expected that representatives from traffic engineering will remain involved at the implementation stage to support reviewing traffic control and management plans, evaluating work zone safety, and ensuring compliance with work zone policies. Because some ATM strategies depend on structures to function and pavement designs to support traffic loads under dynamic shoulder use, representatives from the agency’s structural department, geotechnical department, and pavement department are likely to remain involved during construction. This involvement from the civil design area for some ATM implementations is atypical to a traditional ITS implementation. ATM strategies such as adaptive ramp metering or adaptive

traffic signal control may have limited disruption during implementation and will not have the same impact during implementation as infrastructure-based strategies.

In many agencies, representation from project-specific local staff will increase during the implementation stage. Many state DOTs have divided their agency field support by geographic units and subunits; project implementation is often led at the local level by staff within these divisions or districts. Supervision includes identifying a resident engineer and inspection staff to monitor the progress of the contractor. Similar to a traditional ITS project, an ATM implementation will include elements such as telecommunications networking, electronic roadside devices, central office networking, and software acquisition and integration. In response, many agencies have created implementation teams or specialists who focus on ITS projects or have staff able to provide technical assistance to the local project delivery staff. Because ATM is a new project type for most owner agencies, it is recommended that agencies err on the side of over-participation by the subdisciplines within the organization to provide a broad and deep skill set that is agile and responsive to issues as they arise.

In addition to the field construction and systems integration that must occur during implementation, a host of operations, maintenance, and coordination partners must be involved in support of a successful opening day of the project (Levecq et al. 2011). Furthermore, the public information office should be engaged with the project to inform highway users about the project concepts and system operations. A high level of outreach must be included in ATM deployment to familiarize the public with the new system and system features. These partners and the recommended activities of each are presented in Table 8-2.

Table 8-2. Coordination partners and activities.

| Partner | Activities |

|---|---|

| TMC Operations |

|

| Motorist Assistance Patrol Operators |

|

| Local Agency Transportation Partners |

|

| Transit Operating Agencies |

|

| Enforcement Agencies and First Responders |

|

| Tow and Recovery Agencies |

|

| Maintenance Crews |

|

| Public Information Office |

|

| Project Managers for Adjacent Projects |

|

| Procurement Office |

|

Contractor Roles and Responsibilities

During the implementation phase, the most crucial partner to be involved in all facets of the project implementation will be the contractor. The contractor can be a leader in facilitating the stakeholder coordination effort. Many of the attributes of a good contractor are self-evident and follow well-known project management practices such as the following:

- Prepares and maintains a proper resource-weighted schedule with a clearly delineated critical path.

- Communicates proactively and frequently, and is transparent with unambiguous progress reporting.

- Develops and maintenance thorough documentation through delivery of as-built plans.

- Understands systems integration and systems testing, and has access to systems integration and network specialist resources throughout the life of the project.

- Maintains a strong and ongoing relationship with the software provider throughout the life of the project.

- Administers a proactive risk management plan and risk mitigation program.

- Takes initiative to engage third parties that may impact the project’s critical path, such as resolution of utility conflicts and acquisition/coordination of power connections.

- Coordinates proactively with other projects in the study area and incorporates those activities into the project schedule and risk management plan.

- Approaches proactively permitting that mitigates schedule risks.

- Willing to consider value engineering approaches when technology changes or other changed conditions lead to potentially improved processes and/or mutually beneficial modifications.

- Establishes in-place SOPs and the management structure to support the implementation of those SOPs effectively throughout the contractor team.

- Establishes a well-defined, strong, documented, and enforced safety program.

The effectiveness of the contractor team will have a direct impact on the progress of the project implementation. All coordination efforts should be reflected within the overall project schedule and managed through a partnership between the owner agency’s project manager and the contractor. This coordination will be especially critical for elements such as software integration, training, and maintenance.

Established Working Groups and Forums

For agencies with mature freeway management systems and incident management programs, it is likely that there are forums, processes, and communication channels in place to facilitate stakeholder interaction—including regional incident management committees, ITS and technical reference manual committees, and regional ITS and transportation demand management committees.

When available, these existing stakeholder coordination mechanisms can be leveraged and modified when necessary to support the implementation of ATM strategies. These modifications may include additional coordination meetings, working sessions focused on the ATM strategies and projects, and expanded membership to include partners not previously involved. An example from the Phoenix, Arizona, metropolitan area is the AZTech Operations Partnership—a longstanding, volunteer partnership of state, county, regional, and local transportation agencies, in addition to traffic incident management representatives. AZTech provides several working groups and committees to engage staff from traffic management, traffic and TMC operations, incident management, and public information/communication. Information is shared with these groups on ATM implementations, such as multiagency adaptive traffic signal projects.

Operational challenges and issues can also be discussed, with potential solutions suggested by the participants. This partnership helps keep agencies informed and actively engages participation in future ATM-related projects.

In locations where such forums or processes do not exist, it is suggested that one or more standing committees be established to maintain scheduled information sharing and dissemination, risk management, and issue resolution around the operations, maintenance, and outreach for ATM strategies.

Software Development and Implementation

Software is a critical component of an ATM implementation, and in many instances, new software (or software updates to existing traffic management systems) may be needed to enable the full operation of ATM strategies. In some cases, ATM can leverage existing systems used for detection and monitoring (through CCTVs or DMSs). For new capabilities such as VSLs, LCSs, or new formats of DMSs and other sign technologies, new software is needed. For an ATM implementation, the overall system will benefit from integrating subsystems to leverage the full range of capabilities of the overall ATM software solution. The integrated software must be operational and ideally have all interfaces with new or legacy platforms in place prior to activating the ATM system.

Software Delivery Models

Similar to the diversity of the project delivery models that were previously presented, the procurement and deployment of software can be achieved through an even more diverse range of delivery methods. Some of the vendors that have implemented or are currently developing software packages to operate ATM deployments include Parsons—previously known as Delcan—(Intelligent NETworks), Southwest Research, and Kimley-Horn (KITS). For deployments in both Washington and Minnesota, the respective state DOTs chose in-house resources to develop their ATM software. This approach built upon their existing ITS platforms and provided an effective approach for expanding existing infrastructure to support the ATM system. The Virginia DOT requested that its current ITS software vendor modify the existing commercial advanced transportation management system (ATMS) offering to incorporate the ATM functionality. The Oregon DOT acquired the services of a software developer to enhance its existing ATMS software.

As shown with this sampling of existing implementations, agencies have yet to demonstrate a true trend in the development and deployment of ATM software. While software procurement choice is a design decision, incorporating the software development, training, and acceptance during implementation is critical to the successful operations of the ATM on day one. Chapter 3 of this document highlights the key systems engineering steps, including the development of the concept of operations and requirements, which outlines the core planning and design steps to define ATM software needs and capabilities. Engaging the right stakeholders in these processes will help ensure that multiple perspectives on software and system needs, functions, and capabilities are captured before embarking on an implementation effort.

Regardless of the software procurement choice—in-house development as an extension or module of the existing platform, in-house development as a stand-alone platform, commercially developed as an extension or module of the existing platform, or commercial development as a stand-alone platform—it is critical to complete the following steps during implementation:

- Confirm all software requirements with the selected solution provider as soon as practical.

- Confirm that all software requirements align with the identified standards and components that will be utilized as part of the project.

- Confirm all requirements necessary for interfacing with legacy platforms are identified for effective implementation.

- Understand how the ATM software will influence TMC operations and what supporting materials, procedures, or training may be needed for operations staff.

- Confirm that all software requirements align with the concept of operations so the system will deliver the stakeholder’s vision.

- Refine SOPs during the requirements development and software implementation phases.

- Develop a training plan and user manual to support the implementation of the software.

- Develop a comprehensive laboratory environment that consists of actual devices in concert with simulated devices to simulate and test the operational, safety, and failure modes of the ATM system.

Software Development Resources

Software development for an ATM system can be overwhelming for an agency, even if existing ATMS software is already in place. Because ITS projects are required to follow the systems engineering process (as noted in Chapter 3), applying these tools to the ATM software component facilitates a more efficient implementation. The primary goal for software development is to ensure from day one that the built system achieves all the defined requirements and performs as the agency had envisioned. The following available systems engineering resources provide an agency with key activities, recommendations for testing, and recommended development practices to manage the progression of software within the defined budget and schedule:

- Section 4.6 of the Systems Engineering for Intelligent Transportation Systems: An Introduction for Transportation Professionals (FHWA 2007).

- Systems and Software Engineering—Life Cycle Processes—Requirements Engineering (ISO/IEC/ IEEE 2018).

- Systems Engineering Guidebook for Intelligent Transportation Systems (FHWA 2009).

Systems Engineering Traceability

As noted in Chapter 3, the systems engineering process should be applied to reduce risk and verify functionality at key steps. Systems engineering provides a step-by-step process for system, subsystem, and unit-level requirement development. Each step further refines the previous, ultimately creating the detailed design requirements that are used for the development of both the plans, specifications, and estimate package and software.

The systems engineering process builds in checkpoints at key stages to verify that the developed system meets the defined requirements, as well as the needs and expectations of the agencies undertaking them (Knopp 2022). This process is intended to minimize and control system risks early to limit the number of potential changes to the system once development is complete. Each testing and verification step should occur only after the previous step has been completed and accepted. The final validation step maps back to the initially identified user needs (as per the concept of operations. See Chapter 3). This final test is intended to confirm that the system was built acceptably, the system works appropriately, and the software was developed accurately.

Agile software development processes represent an iterative approach to software development that focuses on incremental development and delivery, allows for review and feedback throughout the development process, and allows software development to respond to changing requirements or address gaps that may have been present in the initial requirements. Integrating agile processes (notably Scrum, a project management framework) with systems engineering processes can provide a more holistic approach to developing complex software for applications like

ATM, combining the flexibility of agile development while maintaining the best practices and risk management of systems engineering (Staples et al. 2017). Agile methodologies, like Scrum, introduce a new set of processes, including “Sprints” to address specific subsets of prioritized requirements and features. Software is developed, reviewed, and tested incrementally so that any issues uncovered can be addressed quickly and before full development is complete. ATM software development approaches that leverage both agile and traditional systems engineering can benefit from minimized risk during all stages of development.

Construction

The following sections provide information on schedule considerations and risk monitoring during the construction of ATM deployments.

Schedule Considerations

Schedules are critical on any project, but ATM projects involve a complexity of coordination that increases the criticality of the schedule for an effective delivery. A traditional, freeway-focused ITS project can experience a delay with minimal or no impact on the day-to-day operations of the facility. In a typical ATM deployment, the technology component is often an integrated portion of the operation of the facility. Similar to a traffic signal for an arterial roadway, the ATM components—whether they are VSL signs, LCSs, or adaptive ramp meters—are an integrated part of the facility.

ATM implementations often involve civil components, such as shoulder lane improvements, ramp improvements, and gantry and sign structure installations. Delays associated with these civil components can easily impact the daily operation of the facility. Last, the culmination of all subsystems—including the civil elements, field equipment, and central software—must align to deliver a complete solution. This alignment can be challenging with multiple procurement items, delays in the delivery of individual components, and coordination between the civil and technology elements of an ATM.

Schedule management and schedule risk monitoring are critical to the success of an ATM project and require a coordinated schedule that addresses a wide range of project elements, including the following:

- Field construction.

- Central office construction and integration.

- Operations and maintenance.

- Training and SOP development.

- Formal partnership agreements.

- Public education, awareness, and outreach campaigns.

- Development and integration of software into operations, which includes testing, debugging, and training.

Coordinating civil elements within the corridor is crucial to maintaining operations of the facility during construction and includes a large structural engineering and foundation footprint that must be coordinated with existing structures and overhead signing. Roadbed construction must be phased to maintain traffic during tasks such as shoulder enhancements, ramp enhancements, and accident investigations. Finally, the frequency of structures along the corridor must be coordinated to ensure signing consistency as new ATM dynamic and static signage are integrated with existing dynamic and static signage. It also is important that the construction of these civil elements occur in coordination with other projects in the vicinity of the corridor.

Component-level, subsystem, and system testing and training are critical elements that should be integrated into the project schedule as well. These software elements are often programmed and scheduled for the end of the project delivery life cycle and receive less emphasis than the more tangible civil elements. In some instances, the technology and civil components of an ATM project may be managed by different groups and on completely different schedules, with ad hoc coordination throughout the process. For a successful first day of operations, it is crucial that system testing be completed on time and that all operations, procedures, and protocols be aligned with the defined system and associated software.

Most agencies and contractors use extensive tools and methods for managing, tracking, and monitoring schedule adherence. When compared to traditional ITS projects, ATM projects typically involve a larger civil component, the introduction of new subsystems and technologies to support traffic management, and a more intense software component to support strategy implementation.

Monitoring Risks

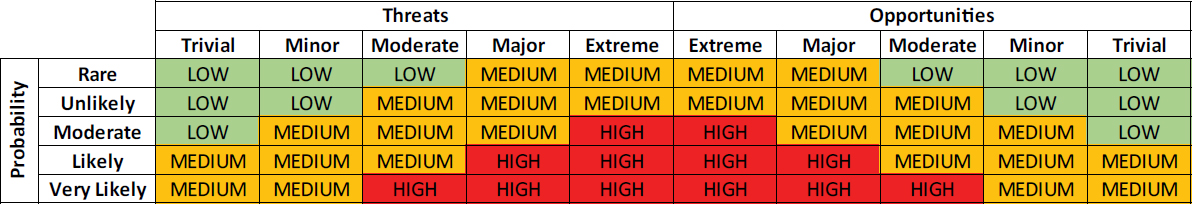

Managing these additional complexities warrants an enhanced risk management regime, as recommended in A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (Bolles and Fahrenkrog 2004). In such a regime, all project risks are quantified and rated by probability and impact of occurrence. Risks can be either a threat or an opportunity for the project. Typically, the risk assessment is applied using either a 3 × 3 or a 5 × 5 matrix, as shown in Figure 8-2.

Once identified and rated, a risk response plan should be developed, including the assignment of an appropriate mitigation response. Risk management, analysis, prioritization, and mitigation strategies should be ongoing parts of project management throughout the development and implementation of the project. The frequency of revisiting and updating the risk management plan should be commensurate with the size and pace of the project.

Pilot Operations and Rollout

ATM may introduce new strategies that will require monitoring and refinement once implemented. Agencies may need to review and modify algorithms and operating strategies to achieve desired performance outcomes. A certain level of testing can be done in the software environment prior to deployment and through modeling and simulation, but actual operations will help identify any changes or updates that may need to be made, particularly for software processes, to help align the ATM system and strategies with intended and desired performance.

Examples of piloting strategies before or during initial operations include the following (Schroeder 2020):

- The Nevada DOT (NDOT) built new software for the I-15 ATM system in Las Vegas and included a test corridor so that operators could become familiar with the ATM system capabilities

Figure 8-2. Probability and impact matrix (Source: Bolles and Fahrenkrog 2004).

- prior to fully launching the system (Schroeder 2020). The I-15 ATM system was set to go live in March 2020. This date coincided with significant drops in traffic volumes on the freeway, which allowed operators at the TMC time to get more familiar with the new system. The success of the I-15 ATM has prompted NDOT to examine ATM on a statewide level, including weather-specific ATM strategies for corridors in northern Nevada, which is prone to winter weather.

- Adaptive traffic signal control technologies and adaptive ramp metering require a preliminary effort to fine-tune the adaptive algorithms to ensure the system is producing the desired operational results. State DOTs in Oregon and California use system-wide adaptive ramp metering, where rates are calculated based on the current density between ramps, and some adaptive operations can also factor in ramp queues. Agencies deploying adaptive ramp meter strategies can assess performance based on a range of factors, such as metering rates in response to mainline volumes and ramp queues with the potential for disruption or queues extending to the interchange or onto local roads. Close coordination with adaptive system vendors is typically required to fine-tune these processes.

- Initial ATM operations can provide agencies with valuable information on potential strategy improvements, such as traveler response and compliance or the need for operational adjustments. During the first week of operations for the I-670 ATM in Columbus, Ohio, which includes flexible use of the shoulder during peak congestion, Ohio DOT staff waited until the freeway reached congested conditions before opening the shoulder. Based on that experience, staff is now trained to open the shoulder before bottlenecks and congestion occur on the freeway, which has resulted in improved traffic flow.

Public Outreach and Awareness

A successful ATM implementation requires buy-in from key stakeholders, including travelers. Users of the transportation system where ATM is being deployed will likely see many new signs, instructions, and strategies; compliance with ATM operating strategies means that travelers need to understand not only what they are being asked to do but also why they are being asked to do it.

Providing information to travelers in advance of new ATM strategies being implemented is a key first step. Making travelers aware of what new technology will be deployed in corridors; why the agency is implementing these technologies; how travelers should respond when they see new signs, speeds, and displays; and what benefits these ATM investments are intended to have are all key pieces of the messaging that will help make the ATM strategy successful. Some examples of these communication strategies include the following:

- Branding: Many agencies have opted to brand their ATM programs (or corridors where ATM is implemented) to help foster awareness and recognition. In Michigan, the ATM corridors are called “flex lanes,” including the pilot deployment on US-23 and subsequent corridors where similar strategies are being implemented. State DOTs in Ohio and Minnesota use the term “Smart Lanes” for their ATM corridors.

- Media campaign: Branding helps support a consistent media campaign where agencies can leverage local news media to share information about upcoming ATM implementations. News media partners can share information about the project, including what travelers will see and how travelers are expected to respond. Press releases and press events can help notify the public about ATM launches or expansions. Media can reach a wide regional audience.

-

Websites: Many agencies have dedicated websites to highlight ATM programs and implementations; several include images, videos, how-to-use guides, and descriptions of the technologies that are part of the ATM system. Examples include the following:

- Michigan DOT “Flex Route”: https://www.michigan.gov/mdot/travel/safety/road-users/flex-routes.

-

- Washington State DOT “Active Traffic and Demand Management”: https://wsdot.wa.gov/travel/operations-services/active-traffic-and-demand-management.

- Ohio DOT “Smart Corridors”: https://www.transportation.ohio.gov/programs/traffic-operations/resources/smart-corridors.

- Videos: Videos of actual or simulated operations of different ATM strategies give travelers helpful insights into what the technology looks like in operation. Narrated videos can describe what the technology is, how it works, and what benefits it may provide.

- Social media: Many agencies are active users of various social media platforms to share project information and alerts about the transportation system. Tools such as X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, and others can provide short notifications or more detailed project information. Social media also allows for interaction with travelers; many agencies have indicated that they monitor replies and responses on social media to gauge user perceptions.

Public outreach and awareness for ATM require ongoing effort. While there is likely a concentrated campaign during construction and leading up to implementation, consistent messages before implementation, during construction, and once the ATM strategies are operational will help improve traveler acceptance and awareness of the new operating processes. As noted in the ATM Implementation and Operations Guide, both Washington State and Minnesota used multiple outreach approaches to highlight the mobility and safety benefits of the ATM strategies that were being implemented (Kuhn et al. 2017). Media events, group presentations, advertising, websites, emails, and other strategies all focused on highlighting the new ATM systems being deployed and the benefits that the agencies were seeing as a result of ATM.

In Nevada, NDOT and the RTCSNV issued a public survey 1 year after the I-15 ATM went live in Las Vegas. The purpose of the survey was to gauge the public’s understanding of the ATM and identify if there was a need for additional education. The survey asked questions such as whether travelers understood the different symbols that were being used if they felt the VSLs accurately reflected speeds within the corridor, and whether travelers changed their route as a result of the information being displayed. More than 400 people responded to the survey, and the responses were generally positive (Gaisser and Schilling 2023).

As part of the I-670 Smart Lane implementation in Columbus, Ohio, Ohio DOT noted that there was some initial negative feedback on social media about the Smart Lane system and technologies during construction. Once it was launched, feedback from the public was overwhelmingly positive with many travelers noting how much time it saved them on their afternoon commutes (McAdam 2021).

Final Remarks

Successful implementation of ATM builds on a series of processes for planning, concept development, design, stakeholder engagement, and leadership support for new operating strategies. ATM will often require new systems and software, which require careful systems engineering to address a wide range of stakeholder needs and performance objectives. Project delivery considerations are ideally determined early in the process so that an agency and its partners have a strong understanding of the different methods and requirements inherent in specific delivery methods and how these requirements may influence ATM construction, scheduling, and risk management. In some instances, ATM may require additional civil improvements, such as ramp enhancements, shoulder improvements, and/or structural implementation for gantries and additional signage.

This chapter has presented several examples of agencies that have piloted complex ATM strategies through initial rollouts and—using the lessons learned and successful performance outcomes—are preparing to expand ATM strategies to other corridors.

Engaging the right stakeholders in the early planning stages, as well as during construction and software development, is essential to making sure that ATM achieves its desired objectives. In some instances, ATM will require new types of stakeholders—beyond those who may be typically involved in a more traditional ITS deployment—to be included in strategic discussions. For those ATM implementations with a strong civil component, coordinating scheduling and development among multiple agency groups and across several contractors adds increased complexity and risk that needs to be managed. A strong communication plan, an understanding of agency procurement processes, attention to scheduling and lead times, and recognition of any additional requirements (such as unique requirements for projects using federal funds) can help support a coordinated effort toward successful implementation and future operations of ATM.

Chapter 8 References

Bolles, D., and S. Fahrenkrog. (2004). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide). Project Management Institute.

FHWA (Federal Highway Administration). (2007). Systems Engineering for Intelligent Transportation Systems: An Introduction for Transportation Professionals. U.S. Department of Transportation. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/seitsguide/. Accessed June 2023.

FHWA. (2009). Systems Engineering Guidebook for Intelligent Transportation Systems. Version 3.0. California Division, U.S. Department of Transportation. http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/cadiv/segb/. Accessed June 2023.

Gaisser, T., and R. Schilling. (2023). “I-15 Active Traffic Management System.” Presentation to the Active Transportation and Demand Management Cohort Meeting.

ISO/IEC/IEEE (International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission/ Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers). (2018). ISO/IEC/IEEE Standard 29148:2018: Systems and Software Engineering—Life Cycle Processes—Requirements Engineering. https://www.iso.org/standard/72089.html. Accessed October 2023.

Knopp, M. (2022). “Information Memorandum: Systems Engineering for ITS Projects.” FHWA Correspondence, Associate Administrator for Operations, U.S. Department of Transportation. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/int_its_deployment/docs/Information_Memo_Systems_Engineering_for_ITS_projects.pdf. Accessed September 2023.

Kuhn, B., K. Balke, and N. Wood. (2017). Active Traffic (ATM) Implementation and Operations Guide. Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-HOP-17-056. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop17056/index.htm. Accessed May 2023.

Kuhn, B., D. Gopalakrishna, and E. Schreffler. (2013). The Active Transportation and Demand Management Program (ATDM): Lessons Learned. Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-HOP-13-1-018. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop13018/index.htm. Accessed June 2023.

Levecq, C., B. Kuhn, and D. Jasek. (2011). General Guidelines for Active Traffic Management Deployment. University Transportation Center for Mobility and Texas A&M Transportation Institute. Report UTCM 10-01-54-1.

McAdam, J. (2021). “I-670 Smart Lane.” Presentation to the Transportation Research Board Joint Subcommittee for Active Traffic Management Annual Meeting.

Schroeder, J. (2020). Use Cases and Benefits of Active Traffic Management (ATM) Strategies. Enterprise Pooled Fund Study. Publication ENT-2020-3. https://enterprise.prog.org/projects/use-cases-and-benefits-of-active-traffic-management-atm-strategies/. Accessed June 2023.

Staples, B., D. Hardesty, B. Christie, T. Deurbrouch, J. Seder, M. Insignares, and P. Chan. (2017). Applying Scrum Methods to ITS Projects. Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office,

U.S. Department of Transportation. Publication FHWA-JPO-17-508. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/32681. Accessed June 2023.