Selecting, Procuring, and Implementing Airport Capital Project Delivery Methods (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Historically, airport capital construction projects entailed the almost exclusive use of the design–bid–build (DBB) delivery method involving the separation of design and construction services and the sequential performance of design and construction. However, over the past two decades, airports have increasingly been turning to alternative project delivery methods (PDMs)—including construction manager at risk (CMAR), design–build (DB), public–private partnerships (P3s), and other variants or hybrids of these methods—to improve the speed and efficiency of the project delivery process.

Each of these methods has its own set of risks and rewards. At the time of the PDM selection decision, project sponsors must, therefore, have a clear understanding of the relative costs, benefits, and risks of each method to deliver their projects wisely. Equally important is how the PDM is to be implemented, as procurement and postaward contract administration practices can further maximize the benefits of the chosen PDM, thereby creating an overarching project delivery system.

1.1 What Is a Project Delivery System?

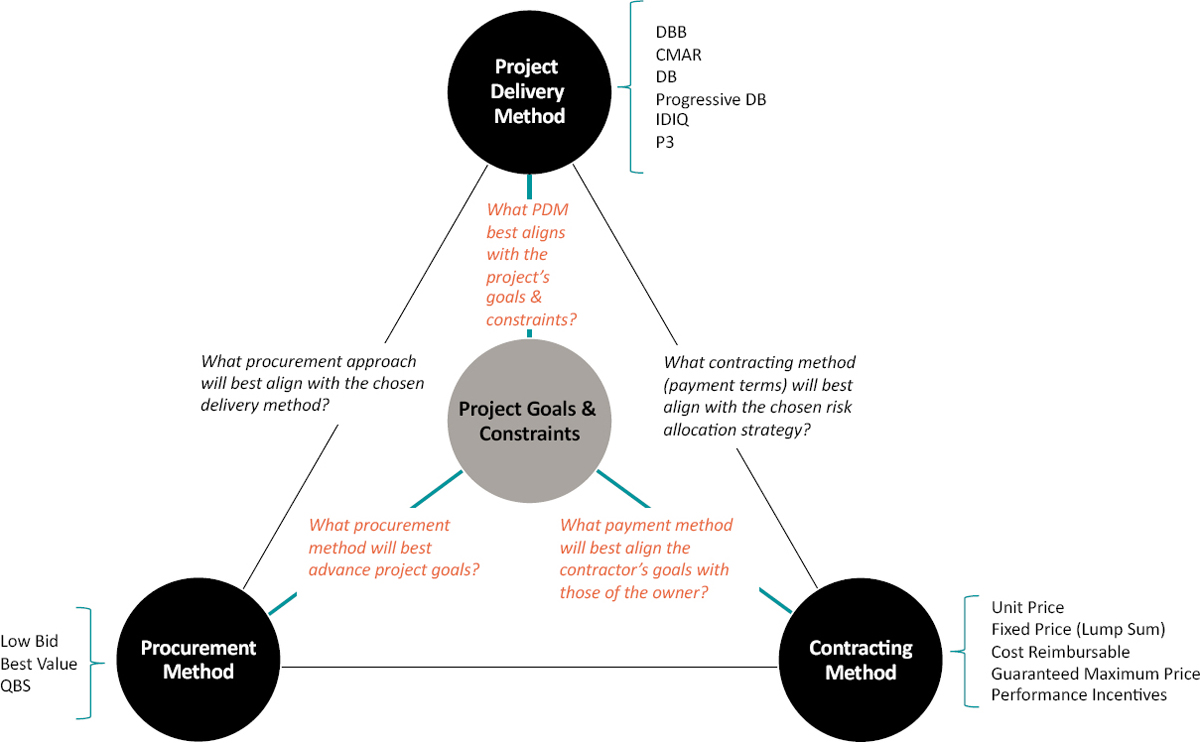

In the broadest sense, a project delivery system refers to the contractual relationships, procurement methods, commercial and financial terms, and management strategies used to take a project from concept through design, construction, and, in some cases, operations and maintenance. As summarized in Figure 1-1, to develop an overarching delivery strategy for a particular project requires determination of the optimal PDM, procurement approach, and contract type that best meets the project’s goals and constraints.

1.1.1 Project Delivery Methods

As used herein, a PDM refers to the comprehensive process used to execute and complete a capital project, including planning, programming, design, construction, and, potentially, operations and maintenance. Commonly used PDMs for delivering major airport capital projects are defined in Table 1-1. (Note that although these definitions are consistent with the prevailing literature, their exact application in practice may vary by owner.)

The airport interviews and surveys conducted in support of the development of this guide revealed the following general themes and observations regarding the PDMs used to deliver airport capital projects:

- “Optimal” PDM. No single PDM is appropriate for all projects and situations. The PDM that will best suit a particular project will depend upon a range of factors, including project goals, project characteristics and constraints, legislative constraints, financial considerations, and the state of the construction market.

Note: IDIQ = indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity; QBS = qualifications-based selection.

-

Most of the airports interviewed expressed strong preferences for using the PDM(s) with which they had the most experience and success. These PDMs essentially serve as their default delivery method unless project circumstances dictate a different PDM be used. CMAR and traditional fixed-price DB were popular alternatives to DBB delivery, particularly for large hub airports with large or complex projects. Some airports were also strong advocates of progressive design–build (PDB). Small and medium hub airports predominantly use DBB delivery but have also begun experimenting with DB and CMAR, particularly for schedule-driven work that does not involve federal funding.

- PDM attributes. Although their preferred delivery methods may differ, the airports generally shared similar perceptions of the different PDMs and the project circumstances under which they would be most beneficial. The reported pros and cons of different PDMs are discussed in detail in Chapter 2 and are included in the PDM attribute tables provided in Appendix A.

-

Drivers for using alternative PDMs. Key factors driving airports to use alternatives to DBB project delivery include a need or desire to

- Accelerate delivery time frames;

- Bring relevant industry knowledge into the delivery process at the right time;

- Address complexity through collaboration and integrated teams (with “complexity” involving such things as complicated operational or phasing considerations, complex designs, and third-party risks); or

- Leverage private-sector expertise and capital.

- Influence of project type on PDM selection. Several of the interviewees noted that certain project types may be better suited to particular PDMs. For example, projects for which design

Table 1-1. Commonly used project delivery methods.

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Construction manager at risk (CMAR) | A PDM in which the sponsor engages the contractor at the early stages of design to provide preconstruction services. Such services typically entail providing input to the sponsor and design team regarding constructability, scheduling, pricing, and phasing. When the project scope is sufficiently defined, the sponsor and contractor negotiate a price for the construction of the project. Also commonly referred to as “construction manager/general contractor” (CM/GC) and “general contractor/construction manager” (GC/CM). |

| Design–bid–build (DBB) | The traditional PDM in which the sponsor completes its own designs or retains a designer to provide design services and then advertises and awards a separate construction contract based on a completed set of construction documents. |

| Design–build (DB) (fixed-price) | A PDM in which the sponsor procures both design and construction services in the same contract from a single legal entity, referred to as the “design–builder,” that commits to a fixed price for the entirety of the work at the time of selection. |

| Progressive design–build (PDB) | A variation of DB in which the design–builder is engaged early in the project development process (typically through a Phase 1 preconstruction services contract) and then collaborates with the owner to validate the basis of design and advance or “progress” toward a final design, associated contract price, and Phase 2 contract for construction services. |

| Public–private partnership (P3) |

A contractual agreement usually involving a public agency contracting with a private entity to finance; design; and construct, operate, maintain, and/or manage a facility or system. Common P3 structures include the following:

|

- and construction are tied to proprietary equipment or systems, such as baggage screening and handling systems, generally are good candidates for a DB approach. Similarly, projects in which the required functionality is readily defined and not subject to wide interpretation of what will meet the specification criteria, such as video surveillance/security systems and runway pavements, generally may also be considered good candidates for a DB approach.

- In contrast, complex terminal projects that require significant stakeholder engagement and complex phasing considerations may be better suited to the more collaborative CMAR or PDB approaches, particularly if the speed of overall project delivery is important and there is insufficient time or resources to take the design to the maturity needed to obtain lump sum bids under traditional fixed-price DB.

- Availability and timing of funds. PDMs that allow for early contractor involvement and the fast-tracking of design and construction can result in accelerated expenditures. It is, therefore, important to consider the project’s anticipated cash flow needs and how such needs align with the airport’s overall revenue streams and likely project funding sources. Therefore, the team in charge of making a PDM selection decision should include, or at least consult with, representatives from the airport’s finance department to understand in advance the timing of such revenues and how and whether they could support a fast-tracked project.

-

First-time implementation considerations. Several of the airports interviewed, regardless of the relative size of their capital programs and the size and sophistication of their capital programs staff, indicated that they adopted some or all of the following implementation strategies to help make their first alternative PDM projects successful:

- Consultant resources were used to help develop solicitation and contract documents and to provide any additional oversight, project management, and training support needed. As a lesson learned, airports stressed the importance of selecting third-party resources that can demonstrate having sufficient experience and technical resources/qualifications in the particular PDM being considered to ensure they are able to provide meaningful assistance with decision-making (even if the consultant must draw upon out-of-state resources or provide specialized subconsultant expertise).

- Industry outreach sessions were held to communicate goals and expectations and to understand the level and types of risk their potential industry partners were willing and able to accept.

- Training was provided [either through industry organizations such as the Design–Build Institute of America (DBIA) or through knowledge transfer sessions with third-party consultant experts] to ensure internal staff understood the key differences between traditional DBB and the alternative PDM being implemented.

1.1.2 Procurement Practices

Procurement practices are the procedures owners use to evaluate and select designers and contractors. Evaluation and selection can be based solely on price (low bid), solely on technical qualifications (qualifications-based selection), or on a combination of price, technical qualifications, and other factors (best value):

- Low bid: An award method in which the bidder/proposer with the lowest bid/proposal price is selected.

- Qualifications-based selection (QBS): An award method that focuses on qualitative criteria such as experience, past performance, and technical approach as the basis for selection. Price is not considered as part of the selection process.

- Best value: An award method that is based on a combination of price and other key nonprice factors such as qualifications, schedule, and technical approach.

Public-sector construction has historically entailed the almost exclusive use of the DBB delivery method, along with the selection of designers on a QBS basis and construction contractors on a low bid basis.

As owners have increasingly been turning to alternative PDMs, they have also adjusted their views on how to select construction teams. While low bid is still widely used, many owners are also using best value and a variety of other innovative procurement techniques, as discussed in Chapter 3, to improve project performance and the value of construction.

1.1.3 Contracting Methods

Designers and builders are typically compensated for their services on the basis of

- Cost reimbursement (with or without a guaranteed maximum or not-to-exceed price),

- Unit rates, or

- Firm fixed (lump sum) pricing.

Each of these contracting methods takes a different approach to the allocation of cost and performance risk. As with PDMs and procurement methods, there is no single contract payment strategy that is appropriate for all projects and situations.

The approach that best suits a particular project will depend on the owner’s project delivery goals, project characteristics, the PDM selected for the project, and market considerations. To help owners align payment terms to project goals and characteristics, Chapter 4 discusses the potential benefits and limitations of common payment mechanisms and performance incentive strategies used in airport construction.

1.2 Overview of This Guide

1.2.1 Purpose and Need

As there is no one-size-fits-all project delivery system, tailoring a delivery strategy to a particular project requires a thorough understanding of the unique advantages and disadvantages of the different approaches available and the typical conditions under which they have been effectively applied.

To this end, this guide addresses the following issues:

- Key attributes of the different PDMs being used to deliver airport capital projects;

- The considerations driving airports to use different PDMs;

- The methods by which airports procure design and construction services, including how these processes are generally implemented under different PDMs;

- The contract types (or payment terms) that best align with the desired project risk allocation strategy, including the use of commercial incentives to motivate contractors to work as quickly and efficiently as possible and/or to meet some other performance objectives; and

- Various postaward administrative tools and strategies airports have been using to integrate contractors into the project team early, encourage communication and collaboration, and drive alignment of all project participants.

1.2.2 Intended Audience

This guide was developed to assist airports of all sizes with the selection and implementation of the most advantageous PDM, procurement approach, and contracting method for a given project. Whether an airport is using a particular delivery method for the first time or has significant experience with the method, the guide is intended to provide useful strategies and tools to support its implementation.

The target audience for this guide is airport personnel responsible for delivering capital projects, although owner’s representatives, architects, engineers, and contractors may also find the guide beneficial for understanding roles and responsibilities in the delivery process and the tools airports may use to administer projects.

1.2.3 Development of the Guide

This guide is based on the processes for selecting project delivery systems and the contract administration practices used by a diverse cross section of airports and other public transportation agencies. It was developed through (1) a review of current literature and contract documents and (2) interviews with airport and industry representatives.

Key tasks performed to support the development of this guide included the following:

- A survey conducted to raise awareness of this ACRP research study and obtain feedback on desired content for the guide (in particular, which PDMs airports had interest in);

- A comprehensive literature review to capture the breadth of PDMs, procurement processes, and contracting types currently being used to deliver airport capital projects; and

- Individual interviews and focus groups with a diverse cross section of 25 airports located across the United States to probe for more specific information and details regarding the selection and implementation of different PDMs, including successful and unsuccessful lessons learned.

1.2.4 Navigating the Guide

This guide is structured to allow the user to quickly locate section(s) of particular interest. It is not necessarily written to be read in its entirety or in a particular order. Some information may be repeated in one or more sections so that each individual section may be understood on its own.

- Chapter 2 presents the range of PDMs used to deliver airport capital projects, from DBB to P3. A qualitative assessment of the advantages and disadvantages of each method is provided, as well as the selection factors driving airports to consider using the different methods. In addition, Chapter 2 introduces an automated Excel-based decision support framework that users may apply to examine how a given project’s specific needs, goals, and risks align with the attributes of the PDMs available.

- Chapter 3 describes the key attributes and advantages/disadvantages of the three main approaches used to procure design and construction services for airport capital projects (i.e., low bid, QBS, and best value), along with the processes used to implement these methods under different PDMs. This chapter also reviews some of the main procurement requirements of the FAA’s grant process and Airport Improvement Program (AIP).

- Chapter 4 addresses commonly used payment methods and other contracting techniques that can be used to allocate project risk and align goals among team members.

- Chapter 5 describes various tools and management strategies that airports have applied to manage the organizational change often associated with incorporating new PDMs into a capital construction program. The chapter also describes various implementation tools being used to support project team integration and collaborative problem-solving, as well as some additional project management techniques that can be implemented to impart more discipline to the management of project scope and budget, particularly when more collaborative forms of project delivery are being used.

Five appendices are included:

- Appendix A provides single-page overviews of the DBB, CMAR, DB (fixed price), PDB, and P3 delivery methods that users may consult as a quick reference to the key attributes of the different methods as well as their potential pros and cons.

- Appendix B contains the technical and price proposal requirements used by Nashville International Airport for a recent best value procurement process.

- Appendix C contains a list of services developed by the Massachusetts Port Authority for a construction manager (CM) to provide during the preconstruction phase of a CMAR project.

- Appendix D contains an example scope of services from a PDB project.

- Appendix E presents the Los Angeles International Airport’s Bradley West International Terminal (Bradley West) project as a case study. The Bradley West project provides valuable insights for many reasons. Aside from being the first major project developed by Los Angeles World Airports since the 1984 Olympics, it was the first major project delivered by the City of Los Angeles under the CMAR process. As a result, the Bradley West project provides important lessons for those aviation agencies that are interested in using an alternative to their traditional approach to capital project delivery. The project also provides some excellent perspectives about what an aviation agency (large or small) might consider as it embarks on a new capital project, particularly if it has not undertaken a major capital project for a long period of time.