Selecting, Procuring, and Implementing Airport Capital Project Delivery Methods (2024)

Chapter: 3 Procurement Practices

CHAPTER 3

Procurement Practices

3.1 Introduction

The procurement of designers and contractors is an integral part of selecting and implementing the most appropriate project delivery method (PDM) for any project, including airport capital projects. The decision about which procurement method is best for a given project is based on a variety of factors. For public-sector owners, the most important questions are statutory and regulatory: What procurement flexibility or constraints, or both, are associated with a particular delivery method? Once they determine their options, public owners can operate like private-sector owners and base their procurement decisions on project attributes and goals, including the likely duration and complexity of the procurement process itself.

Although design and construction services may be procured in a variety of ways, the most common widely used procurements methods are the following:

- Low bid: The bidder/proposer with the lowest bid/proposal price is selected.

- Qualifications-based selection (QBS): The award focuses on qualitative criteria such as experience, past performance, and technical approach as the basis for selection. Price is not considered as part of the selection process.

- Best value: The award is based on a combination of price and other key nonprice factors, such as qualifications, schedule, and technical approach.

As discussed in Chapter 2, public-sector construction has historically involved the almost exclusive use of the design–bid–build (DBB) delivery method. Under this method, owners select designers on a QBS basis and construction contractors on a low bid basis. However, as both public and private owners have turned to alternative PDMs over the past 25-plus years, they have also changed their views on how to select construction teams. While low bid is still widely used, an increasing number of owners are using best value to select construction contractors on projects delivered through an alternative PDM. Such owners are also routinely short-listing proposers and using a variety of innovative procurement techniques, such as alternative technical concepts (ATCs) and confidential one-on-one meetings with prospective proposers.

This chapter describes the attributes of the three main procurement approaches, including the processes used to implement them under particular PDMs. It also discusses some of the innovative procurement techniques referenced in the preceding paragraph and industry best practices for the implementation of design–build (DB). Finally, this chapter reviews some of the procurement requirements of the FAA grant process and Airport Improvement Program (AIP).

3.2 Low Bid

3.2.1 Overview

As its name suggests, low bid is an award method by which the owner selects the bidder/proposer with the lowest bid/proposal price. Many state statutes mandate that construction contracts be awarded through a low bid procurement process. These statutes were enacted as part of the design–bid–build (DBB) process and are consistent with legislative efforts to ensure procurement integrity and eliminate bidding fraud and corruption. Aside from having the low bid, the bidder must also be “responsive” and “responsible”:

- The term “responsive” speaks to the bidder having submitted a bid that is technically compliant with the procurement documents (e.g., the bid is signed and dated).

- The term “responsible” addresses the requirement that the bidder meet certain standards related to its capabilities and conduct, such as having

- Adequate financial resources,

- A satisfactory performance record, and

- A satisfactory record of integrity and business ethics.

3.2.2 Advantages and Disadvantages of Low Bid

In addition to deriving the public policy benefit of procurement integrity, owners may obtain some other benefits by selecting contractors on the basis of low bid. Some of these advantages are as follows:

- Bidders are incentivized to provide their best and lowest price to win the competition, resulting in owners obtaining the lowest initial price for their capital projects.

- Low bid awards are based on a relatively simple, transparent, and objective evaluation criterion (i.e., the low price), in contrast to procurements that consider evaluation criteria not related to price, which can be complicated and subjective.

- The low bid system is familiar to the industry, as virtually all owners, designers, and contractors understand how the process works and its relative risks and rewards.

There are also some downsides to using a low bid procurement process, particularly on complex projects that are delivered through something other than DBB. For example:

- The initial low bid price might not result in the ultimate lowest cost or best value.

- Bidders are not motivated to offer or provide enhanced performance (e.g., cost, time, quality).

- To provide their lowest price to win the competition, bidders may take unrealistic or overly optimistic views of their ability to perform, which may lead to potential disputes during project execution when they try to protect their commercial interests. There is a long history of low bid construction projects having experienced conflicts, delays, claims, and cost overruns to owners.

- Absent short-listing or prequalification, low bid excludes consideration of important nonprice considerations, such as a bidder’s technical proposal, past performance, or qualifications.

This last point is significant. Stated simply, if Bidder A (the most competent, experienced, and client-friendly contractor among all bidders) is $1 higher than Bidder B (the least competent, least experienced, and most claims-oriented contractor among all bidders), the owner must nevertheless award to Bidder B. Moreover, if an owner is institutionally committed to using the low bid process, there is virtually no incentive for Bidder B to treat the owner fairly on the project—there are no practical adverse consequences for its failure to do so, as long as it remains a responsible bidder.

3.2.3 Implementing a Low Bid Procurement Process

Low Bid with DBB Delivery

Low bid procurements are most closely associated with DBB, and the procurement process for DBB is well established. Generally, the owner develops the project design to 100% completion, either in-house or with a third-party design firm, and then advertises the project to the construction contracting industry. The bidding documents are contained in an invitation to bidders, which provides, among other things, instructions for bidding, design documents (i.e., plans and specifications), and the form of construction contract. While the amount of information requested by the owner in the bid form may vary in level of detail, the most significant number is the total bid price. The bidder’s bid is contained in a sealed envelope and opened in a public setting. The lowest responsive, responsible, bidder is awarded the contract.

Because one of DBB’s attributes is to open the competitive field to all responsible bidders, DBB procurements are typically run on an open competition basis, in which any contractor that has the ability to provide performance and payment bonds can compete. As noted above, this is one of the potential disadvantages of using low bid procurement. Many public agencies are concerned about whether an open competition procurement process will result in an award to an inexperienced construction contractor who is disincentivized to be a cooperative business partner. While public agencies have less flexibility under DBB to narrow the bidding field, they do have some options, as described in Box 3-1, depending on their procurement authority.

Low Bid with DB Delivery

Low bid procurement has been used to some degree on traditional fixed-price DB projects, although it is not the predominant way that owners award DB contracts. The low bid procurement for traditional DB generally involves an owner conducting a one- or two-step process:

- One-step process: This is similar to the qualified sealed bid process used with DBB, as discussed in Box 3-1. The procurement is based on a request for proposal (RFP) that asks for a qualification or technical package, or both, as well as a sealed price proposal. The qualifications/technical package is evaluated, after which the price proposals of those bidders that are deemed acceptable (i.e., whose qualifications pass) are opened, with the lowest proposal price being awarded the contract.

- Two-step process: The first step involves developing a short list of the most highly qualified proposers on the basis of a request for qualifications (RFQ). In the second step, the short-listed proposers submit separate technical and price proposals. The technical proposals often contain design concepts, management plans, and detailed construction schedules. These are evaluated on a pass/fail basis, and the sealed price proposals of those that pass are then opened and the award made to the lowest-priced proposer.

Some owners, such as the Virginia Department of Transportation, use the one-step process to speed DB procurement on relatively noncomplicated projects. A benefit in doing so is that a one-step process does not result in a short list, which expands the playing field for construction contractors that have limited DB experience.

The low bid process has also been used on some high-dollar, complicated civil projects. For example, the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority used the two-step process to award a $1.3 billion DB contract to a joint business venture of Clark Construction and Kiewit Construction for Phase 2 of its Dulles Corridor Metrorail Project.

Agencies of the federal government have used low bid for DB procurements under a process called lowest price technically acceptable (LPTA) source selection (48 CFR § 15.101-2). As with

Box 3-1. Narrowing the Bidding Field to Qualified Bidders Under a Low Bid Approach

To minimize the possibility of a low bid procurement process resulting in an award to an inexperienced construction contractor, some owners have been able, under their procurement authority, to narrow the bidding field through two processes: qualified sealed bid and the prequalification.

Qualified Sealed Bid Process

Under this approach, a bidder is required to submit, in addition to its sealed bid, a separate qualifications package that provides information deemed important to the owner (e.g., past performance, key personnel, safety record). The owner will evaluate the qualifications package and then open the sealed bids of only those bidders whose qualifications meet or exceed the owner’s minimum qualification requirements. Award is then made to the qualified bidder with the lowest bid price.

Prequalification Process

Another approach is prequalification, which most public agencies have the statutory or regulatory power to implement. These statutes or regulations generally fall into the following categories:

- Administrative prequalification. This is a prequalification process that a construction contractor must follow to qualify to submit bids on construction projects for a particular agency, such as a state department of transportation. The submissions often include financial statements, available equipment and personnel, and previous work experience.

- Project-specific prequalification. This is a prequalification process that is associated with a single project. This process normally address project technical/procurement factors that are considered essential for the success of the given project, including past experience with building certain technology or key project personnel.

Project-specific prequalification can be controversial and hard to implement, as it may involve some level of subjectivity. Contractors often see it as an attempt by the public owner to skirt the full and open competition requirements of the DBB process and argue that the owner is unfairly penalizing the contractor for its performance on other projects. Contractors are also unafraid of contesting the prequalification decision, and there can be a challenge in determining what past experience is necessary. For example, if an airport owner wanted to prequalify construction contractors for a DBB procurement on an estimated $100 million concourse renovation, how would the owner define applicable experience? Can the owner require that contractors have completed 3 similar projects at a contract value of at least $100 million over the past 5 years? While that would seem logical, what if a contractor had five similar renovations, but each with a value of around $50 to $75 million? What if a contractor just had one similar project, but it was $200 million and completed 6 months previously? Stated simply, trying to identify precisely what project-specific prequalification criteria would be considered rational can be a slippery slope, particularly given that the point of DBB is to allow open competition and select on the basis of low price.

the one-step process described in the preceding paragraph, the LPTA method is a competitive negotiation source-selection process in which the nonprice factors of a proposal are evaluated to determine which proposals are technically acceptable and an award is then made to the technically acceptable offeror with the lowest price. An LPTA is generally procured on a two-step basis. Federal agencies claim to use LPTA only when projects are simple and there are benefits to receiving anything more than the minimally acceptable requirements. The scope on LPTA projects is primarily prescriptive and clearly defined and does not seek innovative design alternatives.

The Design-Build Institute of America (DBIA) has been sharply critical of LPTA and published a position statement on the subject, “Federal, State & Municipal ‘Lowest Price Technically Acceptable’ Procurement” (DBIA n.d.). In this statement, DBIA said that LPTA “does not provide best value to the government or the taxpayer for the acquisition of professional design-build services where technical solutions, quality, schedule, past performance and innovation are key components in the creation of the value sought by the government in the provision of the services.” It based this position statement on the following contentions:

- LPTA generally eliminates any consideration of the past performance of a potential contractor in final source selection.

- LPTA seriously impedes collaborative culture during the proposal development and execution of the project, as this method is a low bid selection that comes with an associated and well-documented myriad of problems, conflicts, delays, and cost increases.

- LPTA makes it virtually impossible for the parties to meet or exceed project goals and bring a project to completion on time and with little or no adversarial disputes, claims, or litigation, as it incentivizes design–builders to merely pass in a pass/fail playing field. There is no incentive to strive for outcomes that measurably add value to the agency and its customers.

- LPTA’s focus on cost creates a strong disincentive to think creatively, maximize value within the project budget, and offer the best team (e.g., key personnel) that is motivated to think creatively on behalf of the government.

DBIA advocates that the that the most effective procurement strategy for DB services is typically either a two-phase QBS or best value approach, which are discussed in Sections 3.3 and 3.4 of this chapter, respectively.

DBIA believes that LPTA is appropriate for purchasing commodities (e.g., office supplies or uniforms) or fairly simple services (e.g., laundry or custodial work) and that the most effective procurement of DB services is either a two-phase best value or QBS approach.

On the basis of DBIA’s input and the pushback from industry, the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) was recently modified to limit the LPTA source selection process (GSA n.d.). These modifications require, among other things, the following conditions to the use of LPTA:

- The agency can comprehensively and clearly describe the minimum requirements in terms of performance objectives, measures, and standards that will be used to determine the acceptability of offers;

- The agency would realize no, or minimal, value from a proposal that exceeds the minimum technical or performance requirements;

- The agency believes the technical proposals will require no, or minimal, subjective judgment by the source selection authority as to the desirability of one offeror’s proposal versus a competing proposal;

- The agency has a high degree of confidence that reviewing the technical proposals of all offerors would not result in the identification of characteristics that could provide value or benefit to the agency;

- The agency has determined that the lowest price reflects the total cost, including operation and support, of the product(s) or service(s) being acquired; and

- The agency’s contracting officer documents in the contract file the circumstances that justify the use of the LPTA source selection process.

3.2.4 Cost-Plus-Time (A+B) Bidding

Some public agencies (particularly state departments of transportation) have modified the low bid process by incorporating the cost of time into the low bid determination. Commonly known as cost-plus-time bidding or A+B bidding, this process generally works as follows:

- The cost, or “A” component, is the traditional bid for all work to be performed under the contract.

- The time, or “B” component, is the bidder’s bid of the total number of calendar days required to complete the project, multiplied by a preestablished, owner-set, dollar value for each day to translate time into dollars. (In the highway sector, this daily rate is often called a road user cost or, simply, a user cost.)

- The cost and time components are added together (i.e., A+B) to arrive at the bidder’s total bid for the project.

- Award is made to the bidder that has the lowest total bid.

A+B bidding relies on the contractor to provide the optimal balance of cost and time.

The total bid value is used only to evaluate bids. The contract amount is based on the bid price (A), not the total bid value. The number of days bid (B) becomes the contract time. Note that the lowest combined bid may not necessarily result in the shortest contract time. This technique encourages bidders to find ways to develop innovative means of reducing overall construction time at the lowest cost and recognizes that there is a strong benefit to the owner and other stakeholders in getting the asset completed and in operation.

3.3 Qualifications-Based Selection

3.3.1 Overview

At the opposite end of the spectrum from low bid procurement is QBS, a procurement method that focuses on qualitative criteria (i.e., qualifications, experience, past performance) as the sole basis for selection. Price is not considered a part of the selection process.

QBS has long been used for procurement of architects and engineers on federal contracts under the Brooks Act, which requires architectural and engineering contracts to be negotiated on the basis of demonstrated competence and qualification for the type of professional services required at a fair and reasonable price. After the passage of the Brooks Act in 1972, a large majority of the states followed with their own “baby” Brooks acts that promulgated QBS selection for design professionals.

Until recently, QBS has not been allowed for the procurement of construction services, given DBB and the requirement to use low bid procurement. However, as public owners were given authority to use alternative PDMs, particularly construction manager at risk (CMAR) and progressive design–build (PDB), QBS (along with best value) became an option for their procurement approaches.

As with PDMs, an owner’s ability to use QBS for construction services is dictated by applicable procurement statutes and regulations. For example, certain states, including Florida and Arizona, specifically allow public agencies to use QBS for both CMAR and DB delivery. (Other state statutes may allow public agencies to use CMAR and PDB but require that price/cost be a selection factor, which constitutes a best value procurement, as described in Section 3.4.)

3.3.2 Advantages and Disadvantages of QBS

QBS offers several distinct advantages for owners that have the authority to use CMAR contractors and progressive design–builders, including the following:

- The owner can select the best-qualified proposer to meet its unique, defined goals for its project.

- Procuring a contractor through QBS will be familiar to most owners, as the procurement is essentially the same as owners have historically used in selecting their design professionals.

- QBS is a relatively inexpensive and speedy process, as it does not require (a) the owner to develop detailed procurement documents needed to solicit a competitive price or (b) the proposer to spend the time or money to develop a fixed-price or detailed technical proposal.

- QBS should have a positive impact on the project’s marketability, as most highly qualified contractors are interested in being selected on the basis of their qualifications. The industry also will likely perceive the owner as one who (a) intends to treat the contractor as a professional, (b) places a high value on forming a collaborative and cooperative relationship, and (c) views the contractor as a strategic partner on the project.

- The owner can work with the winning contractor to define the scope of work, schedule, and other elements of the project, thereby making better-informed project decisions.

Because no price information is exchanged during the QBS procurement process, there are several disadvantages to this process, including the following:

- The owner and successful contractor will ultimately be required to negotiate the price and other commercial arrangements for the project. This can be a time-consuming and challenging process, particularly because the owner will not have the benefit of having competitive prices from other proposers to use as a benchmark.

- The conditions of certain funding sources may disallow procurements that do not consider price, as discussed in Section 3.8 in regard to AIP grants.

- The public may be concerned about the owner awarding a no-bid contract and paying more for the scope of work than appropriate.

This last point can be a major impediment to a public agency’s use of QBS for CMAR or PDB. While the construction industry has had a long history of using QBS procurement for design professionals, it has been infrequently used for construction services. Consequently, even if an owner has the authority to use a QBS process, it may decide that the optics of using that process would introduce more complications than benefits. These owners would instead be more inclined to use a best value process, as discussed in Section 3.4.

3.3.3 Implementing a QBS Procurement Process

QBS with CMAR

Public agencies that have the authority to use QBS on their CMAR projects will use either a one-step or a two-step procurement process. The one-step process generally consists of the following steps, as conceptually depicted in Figure 3-1:

- The agency advertises the project.

- The agency releases an RFQ.

- Interested contractors respond to the RFQ by providing statement of qualifications (SOQ). Typical SOQ requirements include submittal of the following:

- Proposed organizational chart,

- Firm’s project experience,

- Key staff experience, and

- Management plans.

- The SOQ may also seek financial statements, safety records, and demonstration of bonding and insurance capacity.

- The agency evaluates the SOQs received, possibly interviews the interested proposers, selects the most qualified proposer, and awards the preconstruction services contract.

- The CMAR contractor performs preconstruction services.

- After the design has been advanced, the parties attempt to reach agreement on the commercial terms for the construction contract.

Note: Owner-driven tasks are shown in grey; contractor-driven tasks are in blue. Adv. = advertisement; Precon. = preconstruction; CM = construction manager; Org. = organization; Exper. = experience; Mgmt. = management; Reqs. = requirements.

- If agreement is reached, the CMAR contractor is awarded a construction services contract.

- If agreement cannot be reached, the design of the project is completed to 100% and the project is typically advertised as a DBB. Depending on the terms of the original solicitation documents and the preconstruction agreement, the CMAR contractor may be allowed to submit a competitive bid or may be specifically precluded from doing so.

Owners that have the option of using a one-step CMAR procurement process will typically exercise that option, as it is efficient and speeds the selection of the CMAR contractor. However, some owners may be required by statute to use a two-step procurement process. Other owners may decide that their interests are best-served by using a two-step process, typically because it gives them the benefit of creating a short list of the most highly qualified CMAR contractors.

The benefit of a CMAR short list is that the owner can optimize the information obtained from the proposers at each stage. For example, the RFQ may request more limited information from the proposers, such as only that related to pure qualifications. The short-listed proposers would then be asked to respond to an RFP that would ask for a more detailed technical submittal, such as projected execution plans, ideas on value engineering, innovative or project-specific approaches to using building information modeling, and other project-specific information. Reducing the number of proposers that submit project-specific information helps both the owner, who has fewer proposals to review, and the non-short-listed proposers, who do not have to go through the effort and expense of responding when their qualifications were not scored into the upper echelon of proposers. It also has a positive impact on making the interview process more efficient.

QBS with PDB

The procurement process for CMAR described in the previous section is essentially identical to how a public agency would use QBS for PDB—depending, again, on what the procurement statutes/regulations are for the public agency. The primary difference between CMAR and PDB from a procurement perspective is that, under CMAR, the agency is selecting a construction contractor, whereas under PDB, the agency is selecting a design–builder (i.e., both a construction contractor and designer). This is more complex than CMAR procurement. For example:

- Selecting a DB team means that the owner may have to make a trade-off as to which entity is more important—the designer or the contractor. What happens if the best designer is paired with a less desirable contractor, or vice versa?

- Because team integration and collaboration are vital to DB success, an agency would want to evaluate that question in making its selection. If the DB team has successfully worked together in a DB relationship on past projects, this is a strong indication that they will in the future.

- The organizational chart of a proposed PDB team is more complicated to evaluate than that of a CMAR contractor. Particularly important is understanding the DB team’s organizational approach to managing the design process.

- Whereas a CMAR contractor might be asked about some constructability or value engineering ideas during a QBS procurement, a PDB team will likely be asked about innovative design approaches and scored on that basis. This is more costly and time-consuming for the proposers and potentially more challenging and time-consuming for the agency to evaluate.

Because owners are highly interested in knowing how the construction and design teams will collaborate once under contract, scenario-based interviews are often a major evaluation factor in QBS procurements for projects delivered through PDB.

There are also differences once the QBS procurement is completed and the fee negotiations begin. While each can be challenging, PDB is much more complicated. The CMAR preconstruction fee is based on a somewhat limited scope of work: preconstruction activities. The PDB preliminary services are substantially greater, as the PDB contractor will not only be performing preconstruction activities but will also be advancing the design. Depending on the type of project, this can be a substantial level of effort. In fact, to address this, some owners divide the preliminary services into smaller, discrete tasks (e.g., confirmation of the basis of design), to deal

with negotiations and any funding constraints and to ensure that the design of the project is on the right track.

QBS Contracting Considerations: One Contract or Two?

In implementing the QBS procurement process for CMAR and PDB, an owner must make decisions on how to contract. The previous sections presume that there would be two contracts:

- One for preconstruction/preliminary services and

- Another for the CMAR construction phase services or PDB final design and construction phase services.

However, this is not always the case. Some owners, because of statute, regulation, or preference, procure a single contract that covers the entire scope of work, and have discrete phases within that contract to address preconstruction/preliminary services and construction/final design and construction.

One compelling reason to use a single contract with two or more phases of work is that some projects, for schedule reasons, will require the CMAR or PDB contractor to start work on early work or enabling packages, such as equipment procurement, site work, demolition, or construction of temporary office facilities or swing space. Performance of these early work packages may be ready well before the design has been sufficiently advanced (or the parties are ready) to start negotiations on the full construction phase of work. Additionally, the construction contract is the document that generally addresses insurance, bonds, and other major commercial issues that affect the contractor’s site activities. A typical preconstruction or preliminary services agreement is not robust enough to do this.

3.4 Best Value

3.4.1 Overview

While QBS provides owners with a strong opportunity for project success by bringing the most qualified CMAR contractor or design–builder to the project, many public agencies require price/cost to be part of their evaluation criteria. This is frequently driven by the applicable procurement authority. It is also sometimes based on owner preference, when the owner feels compelled to have some price competition or is concerned about how the public would view a procurement for construction services being made only on the basis of qualifications. As a result, many public agencies turn to the best value procurement process.

Best value procurement is an award method that is based on a combination of price and other key nonprice factors—typically identical to those that would be considered under a QBS approach. Consequently, in addition to receiving a technical/qualifications proposal, the owner will also receive a price proposal.

While there are many ways to determine best value, all involve the owner ultimately answering the following two key questions:

- How important is price relative to nonprice criteria?

- How will the nonprice criteria be scored?

It is important for owners to remember that the evaluation of virtually all nonprice factors is inherently subjective. Even if one is using the numerical scoring associated with the weighted criteria approach, the evaluator is still required to make a determination of how many points to assign to either a qualification or technical concept. If a factor has been allocated 10 points, some evaluators may think a good idea is worth 10 points, while others may find that it is worth 5 points. Although the price–technical trade-off process might appear to be even more subjective, it has the benefit of being the way many consumers buy on their own behalf—is the difference in price for the highest-quality TV, car, or bottle of wine worth it? Importantly, public agencies that have used price–technical trade-offs for their DB procurement (e.g., the federal government and state of Maryland) have been supported by case law holding that the agency has broad discretion to determine which proposals they find to offer best value.

Common ways owners determine which proposer offers the best value include weighted criteria, price–technical trade-offs, and fixed price/best proposal.

Weighted Criteria

Weighted criteria involve the owner establishing several discrete evaluation factors and then assigning weights to those factors on the basis of each factor’s order of importance. For example, an owner might decide that price is slightly more important than nonprice factors and establish 60 points for price factors and 40 points for the total of all nonprice factors.

Nonprice factors are also typically broken down into several predetermined criteria with assigned weights. This enables each criterion to be evaluated and scored. The technical proposal is evaluated and scored first. Once the total technical score has been developed, the owner evaluates the price component.

Generally, the lowest proposed price is assigned the highest price points (e.g., 60 points) and the remaining proposed prices are assigned a score proportional to the lowest proposed price. The proposal with the highest combined score for technical and price is awarded the contract.

Price–Technical Trade-Off

Some owners prefer not to be bound to the rigors of the numerical process associated with a weighted criteria approach and instead use a price–technical trade-off process. Under this process, the owner

- Evaluates all nonprice criteria by using either an adjectival score (e.g., excellent, very good, good) or a predetermined numerical scoring system,

- Ranks the technical proposals, and

- Opens the price proposals.

If the proposer with the highest-ranked technical score also has the lowest price proposal, that proposer is awarded the contract. However, if the highest-ranked proposer has offered a price that is higher than the other proposers, then the owner will make an assessment of whether its interests would best be served by paying more money for the better qualifications or technical approach, or both. In making this assessment, the owner analyzes the differences between the competing proposals and makes a rational decision based on the facts and circumstances of the specific acquisition.

Fixed Price/Best Proposal

This process is intended to remove price competition from the selection process and focus on competition based upon what the proposer is offering to the owner. The owner stipulates the contract price in its solicitation and then awards the contract to the proposer with the best proposal. The best proposal is typically determined on the basis of either weighted criteria (i.e., specific factors identified and assigned numerical weights by the owner) or adjectival scoring, similar to that described for the price–technical trade-off process.

3.4.2 Advantages and Disadvantages of Best Value

Best value offers many of the same advantages for owners as QBS. However, it also has distinct advantages and disadvantages. Some of the primary advantages are as follows:

- The owner is able to select a highly qualified proposer to meet its unique, defined goals for its project, particularly when the owner is using a two-step process that results in a short list. This is a bit different from QBS, in which the highest-qualified proposer is selected.

- Owners can make their selection on the basis of price as well as nonprice factors.

- Price is determined through a competitive process.

As discussed in Chapter 2, there are also some advantages to owners that use best value with traditional fixed-price DB:

- Proposers compete on nonprice factors of importance to the owner, including project schedule, innovation, design, and quality. The design submittals on a fixed-price DB procurement are typically more advanced than those in a typical PDB procurement, which means that under fixed-price DB, the owner is obtaining different approaches to the performance of the work as well as firm prices.

- The cost of design and construction, as well as the schedule, is fixed at the time of award.

- The major members of the DB team (including key subcontractors and subconsultants) are generally well integrated, as they work together during procurement to develop competitive solutions along with firm price proposals.

That the proposers provide at least some price elements under best value can result in the following disadvantages for both owners and proposers:

- Procurement costs and time are higher, as the proposers are making a price commitment. This is certainly the case with best value on fixed-price DB projects, in which the proposer will need to be confident of its price commitment.

- The cost for contractors and designers to participate in the procurement process may reduce competition, and owners may have to pay a stipend to obtain market interest.

- There is more potential for conflict, as proposers are pricing some or all of the project in a competitive environment, and if their assumptions are wrong, they may be compelled to file claims.

3.4.3 Implementing a Best Value Procurement Process

Best Value with CMAR and PDB Delivery

The best value processes for CMAR and PDB are substantially similar to the processes discussed in Section 3.3.3 for QBS. The owner first decides whether to conduct a one-step or two-step process and then uses an RFQ or RFP, or both, to solicit appropriate qualifications/technical proposals. Figure 3-2 conceptually illustrates a typical two-step best value procurement process for CMAR and PDB projects.

As with QBS, one-step selection processes are used for projects with a relatively straightforward scope and short delivery time. However, because all public agencies are operating under some form of statutory or regulatory CMAR and DB authority, the options for which type of procurement approach to use are often wholly dependent upon the limitations identified within that authority.

The primary difference between best value and QBS is that, in a QBS procurement, an owner may not seek extensive technical submissions, preferring instead to select on pure qualifications and get the CMAR contractor or design–builder under contract expeditiously. Because some price information will be provided and evaluated in a best value procurement, the owner may prefer to obtain more detailed technical submissions from the short-listed proposers. For example, some owners have implemented their PDB procurements by asking for the proposers’ architectural and green design concepts and scoring largely on the basis of a design competition—and also providing stipends to help defer some of the proposers’ costs in doing so.

As an example of the type of information owners ask proposers to provide in their technical and price proposals, Appendix B presents the proposal requirements included in the solicitation documents for Nashville International Airport’s Concourse D and Terminal Wings PDB project.

As for best value price proposals, there is no standard information that an owner will ask the proposers to provide. However, following are some common examples of what has been solicited:

- CMAR price proposals: CMAR proposers are often asked to provide a proposed fee for their preconstruction services as well as their construction fee (e.g., home office overhead and profit) to be applied if they are awarded the construction phase of the project. Other items

Note: Quals. = qualifications; Prelim. = preliminary.

- that might be sought are general conditions costs for the construction phase, proposed rates for personnel, and bond and insurance rates.

- PDB price proposals: PDB proposers are often asked for the same items that are addressed by CMAR contractors. In addition, owners may ask for design fees, both for the preliminary services phase as well as the complete design of the project.

The price proposals under CMAR and PDB do not include a binding price for the construction of the project. This is one of the distinguishing features of these delivery systems—the final price and commercial terms are negotiated and agreed upon after award. However, some owners have asked for preliminary total project prices as part of the CMAR and PDB price proposal submissions. This is particularly true for PDB, for which some owners have asked proposers to provide an indicative design. There are many complexities to this, as PDB envisions that the owner and design–builder will work together to develop and refine the design. In asking proposers to create an indicative design and submit a price that will be scored on that indicative design, the owner may find some challenges. For example, what if the winning proposer was awarded the contract on the basis of an indicative design and price that were never implemented? What if the ultimate design costs far more than the indicative price?

One of the biggest challenges in implementing best value CMAR and PDB is how much weight the owner should allocate to the price proposal. Because the prices are for only relatively small components of the overall project price, they can be subject to manipulation. If the owner’s price proposal weighting is too high in relation to the nonprice factors, one or more of the proposers might decide to submit an artificially low price to win the job. These proposers know that they will have an opportunity to negotiate the final construction price and have a reasonable chance to make up any shortfalls. If the owner’s price proposal weighting is relatively low, the opposite could happen, and a proposer that believes it has a strong chance of winning on the basis of its technical submission could submit a high price proposal.

Best Value with Fixed-price DB

On fixed-price DB projects, the design–builder will commit to a fixed price (lump sum) at the time it submits a proposal and is awarded the contract. Because of this, most owners use a two-step best value process for procurement, in which the owner creates a short list based on SOQs submitted in response to an RFQ and issues an RFP for technical and price proposals. The RFP will include the owner’s requirements as well as evaluation criteria for both the technical and price proposals.

RFQ Step.

As with the QBS and best value process described earlier for PDB, the RFQ for a more traditional, fixed-price DB project will ask interested proposers to provide, at a minimum, the qualifications of key personnel and the past performance of the proposer’s lead contractor, lead designer, and other key members of the team. Other information may include that discussed previously for CMAR, including financial, bonding, and insurance information.

While more information can be requested, the key for an efficient implementation of a best value procurement process is for the owner to make it cost-effective for proposers to participate. It is also vital for an owner not to overwhelm proposers with submittal requirements that are more appropriate for the short-listed teams under the RFP stage of the procurement.

RFP Step.

Unlike the RFP stage for PDB, the RFP stage for a fixed-price DB project typically involves the short-listed proposers providing a detailed technical proposal that responds to the owner’s RFP requirements. These requirements may be expressed through detailed bridging documents that contain prescriptive requirements, or they may be expressed through performance specifications.

Regardless, the proposers will be spending significant time and money not only to develop a responsive, technical proposal but also to advance the design sufficiently to develop a price for the final project. Because of this, it is not unusual for public owners to provide stipends to the unsuccessful proposers—a subject discussed further in Section 3.5.3.

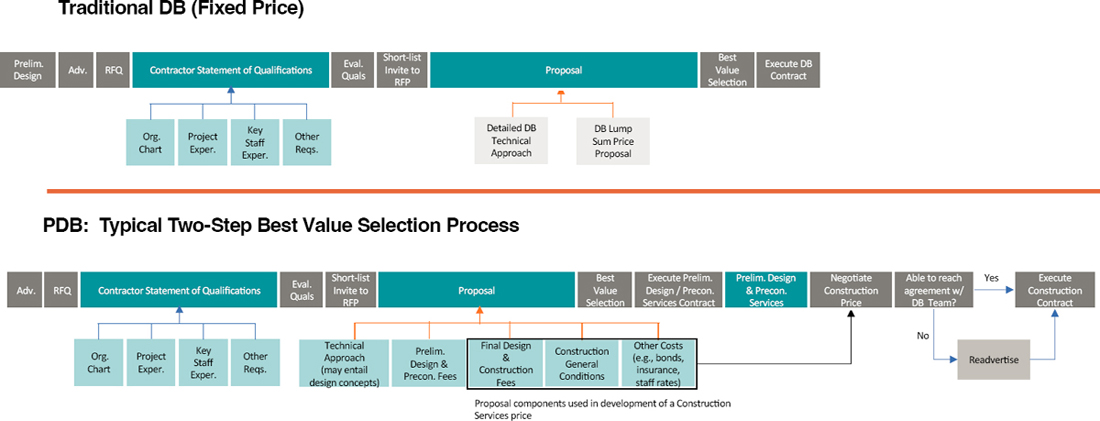

Finally, with regard to to price, it is typical for the price proposal on a fixed-price DB best value process to be a single number, possibly supported by a schedule of values or line items for discrete portions of the work. Some public agencies have also used innovative practices whereby proposers are able to offer to provide additional scope, provided the total proposal price is below a specified limit. Agencies that have done this have generally identified the additional scope and mandated that the proposed scope be offered in a specific order, as opposed to letting the proposers pick and choose what they would like to offer. Figure 3-3 compares a typical two-step best value procurement process for fixed-price DB with that for PDB.

3.5 Innovations in Procuring Alternative PDM Projects

Various procurement innovations have been implemented to support the use of CMAR and DB on public projects. These include ATCs, one-on-one meetings, and stipends.

3.5.1 Alternative Technical Concepts

As noted earlier, some public owners implement their best value procurements on fixed-price DB projects by using a bridging process that prescribes solutions and, in effect, controls the design. In doing this, the owner is not necessarily obtaining the benefit of a DB team’s ingenuity and creative thinking. The ATC process was developed to help address this situation.

An ATC is a request by a DB proposer to modify a contract requirement, specifically for that proposer’s use in gaining competitive benefit during the proposal process. It must provide a solution that is equal to or better than the owner’s base design requirements in the RFP documents. The ATC is used as a way of giving the proposer an opportunity not only to get additional points for its technical proposal, but also to find ways to reduce its price proposal and still give the owner a solution that meets the owner’s design intent.

Implementing an ATC process on a fixed-price DB project requires the owner to consider several factors, including the following:

- The legal authority to use ATCs is not clearly set forth in many state and local DB statutes and regulations, and it is critical for an owner to obtain a legal opinion from the appropriate legal counsel that the use of ATCs is allowable.

- ATCs are considered confidential and proprietary to the proposer. This is necessary for a proposer to invest the time and resources necessary to develop a truly innovative ATC. Most ATCs are first discussed at confidential one-on-one meetings (see Section 3.5.2) with the short-listed proposers, which presume that confidentiality will be maintained.

- Many owners want the right to use ATCs from the unsuccessful proposers. The most common way to do this is for the owner to pay a stipend (see Section 3.5.3) and have the stipend agreement convey the rights to use the proposer’s intellectual property, including the ATCs, to the owner. This has been widely used in the industry and, if the stipend is reasonable, proposers have generally been willing to accept this concept.

3.5.2 One-on-One Meetings

It has become common on both fixed-price DB and PDB procurements to have confidential, one-on-one meetings between the owner and the DB teams. This is an opportunity to discuss

not only ATCs, but also issues that the proposer considers important to providing a responsive proposal.

These meetings also give the proposer an opportunity to help the owner improve the procurement documents by pointing out, among other things,

- Contract terms that are highly problematic,

- Restrictive specifications that might limit the team’s creativity, and

- Major risks that have not been considered.

It is also an excellent opportunity for the members of both the owner’s and the design–builder’s teams to see each other and assess their demeanor, competence, and personality.

3.5.3 Stipends

Because the level of effort to develop a technical proposal for a fixed-price DB project (and sometimes for a PDB project as well) can be substantial, some prospective DB teams will not be willing to participate in the procurement without having a stipend to defray some of the proposal expenses.

Owners willing to provide a stipend generally only pay it to unsuccessful short-listed proposers. As noted above in relation to ATCs, paying a stipend is also a way for owners to gain the ability to use the intellectual property of the short-listed proposers.

3.6 Other Considerations in Procuring Alternative PDM Projects

Other issues for owners to consider when implementing a procurement process for CMAR or DB include short listing, the qualifications of proposers, and relative weights for price and nonprice factors.

3.6.1 Short Listing

If an owner is using a best value approach, there are many reasons to use a two-step procurement process to create a short list. While this has been discussed to some extent earlier in this chapter, there are two key reasons for short listing:

- For projects with strong marketplace interest, owners will be required to spend significant time administering the procurement. Creating a short list enables the owner to spend quality time in one-on-one meetings and interviews with only those proposers who are the most highly qualified.

- It costs industry a substantial amount of money to compete on projects. While putting an SOQ package together is not difficult, responding to an RFP with technical and price submittals can be quite expensive.

The number of short-listed proposers may be a function of statutes or regulations. The federal government’s two-phase DB legislation calls for a range of three to five short-listed proposers. Many public owners short-list to three proposers on the basis of the points discussed earlier as well as on the potential that they will have to pay stipends. The key is for the owner to make an informed and thoughtful decision about why it is short-listing in arriving at the number.

3.6.2 Qualifications of Proposers

When considering what to ask for in the RFQ, owners should include criteria that heavily reward those who have experience with the selected delivery system. Contractors with limited

CMAR or PDB experience often find the preconstruction process challenging. Likewise, proposers who have experience in CMAR but not in DB may find it quite difficult to make the mental shift that is needed to be successful.

3.6.3 Relative Weights for Price and Nonprice Factors

As discussed in Section 3.4, one of the most important issues an owner that plans to use CMAR or DB must determine is how to address price. Depending, of course, on statutory and regulatory authority, an owner first must assess whether its interests are best served by using QBS as opposed to considering price as an evaluation factor. Questions owners consider in making this decision include the following:

- Will having price as an evaluation factor jeopardize the goal of getting the most highly qualified CMAR contractor or design–builder working on the project as soon as possible?

- Will having a price component lengthen or complicate the procurement?

- Will stakeholders accept the selection of a CMAR contractor or design–builder on a QBS basis?

If the owner determines that best value is a better approach, it is critical to understand how to weight price and nonprice factors. Stated simply, 90% price and 10% nonprice is essentially equivalent to a low bid procurement, with all the consequences of that. Similarly, 10% price and 90% nonprice is essentially equivalent to QBS, although it does require the proposers to spend the time to develop a price proposal.

Owners that use weighted criteria often will model different proposal prices against technical scores to determine (a) the likelihood of paying substantially more for the best technical proposal and (b) the likelihood that the worst technical proposal could win because of having a very low price.

3.7 DBIA’s Best Procurement Practices

The industry has published a number of best practices for procuring DB services. For example, DBIA’s Design-Build Done Right® Universal Best Practices (DBIA 2023) identifies two best procurement practices, as well as a number of implementing techniques (i.e., mini–best practices) associated with procurement. These are presented below.

3.7.1 Procurement Plans

One of DBIA’s procurement best practices states,

An owner should implement a procurement plan that enhances collaboration and other benefits of design–build and is in harmony with the reasons that the owner chose the design–build delivery system. (DBIA 2023)

In furtherance of this practice, the DBIA publication offers the following recommendations:

- Owners should use a procurement process that (a) focuses heavily on the qualifications of the design–builder and its key team members rather than price and (b) rewards DB teams that have a demonstrated history of successfully collaborating on DB projects.

- Owners should use a procurement process that encourages the early participation of key trade contractors.

- Owners should develop their DB procurement with the goal of minimizing the use of prescriptive requirements and maximizing the use of performance-based requirements, which will allow the DB team to meet or exceed the owner’s needs through innovation and creativity.

- Owners should develop realistic project budgets and provide clarity in their procurement documents about their budgets, including, as applicable (a) identifying hard contract cost/

- budget ceilings, (b) stating whether target budgets can be exceeded if proposed solutions enhance overall value, and (c) stating whether the owner expects proposers to develop technical proposals that will encompass the entire target budget.

- Owners should consider the level of effort required by proposers to develop responsive proposals and should limit the deliverables sought from proposers to only those needed to differentiate among proposers during the selection process.

- Owners that require project-specific technical submittals (e.g., preliminary designs) for evaluating and selecting the design–builder should (a) use a two-phase procurement process, and (b) limit the requirement for such submittals to the second phase, when the list of proposers has been reduced.

3.7.2 Best Value Procurement

Another one of DBIA’s procurement best practices states,

An owner using a competitive design–build procurement that seeks price and technical proposals should: (a) establish clear evaluation and selection processes; (b) ensure that the process is fair, open, and transparent; and (c) value both technical concepts and price in the selection process. (DBIA 2023)

In furtherance of this practice, the DBIA publication offers the following recommendations:

- Owners should perform appropriate front-end tasks (e.g., geotechnical/environmental investigations and permit acquisitions) to enable the owner to (a) develop a realistic understanding of the project’s scope and budget and (b) furnish proposers with information that they can reasonably rely upon in establishing their price and other commercial decisions.

- Owners should appropriately short-list the number of proposers invited to submit proposals, as this will, among other things, provide the best opportunity for obtaining high-quality competition.

- At the outset of the second phase of procurement, owners should provide short-listed proposers with a draft contract that (a) provides proposers with an opportunity to suggest modifications during the proposal process and (b) enables proposers to base their proposals on the final version of the contract.

- Owners should conduct confidential meetings with short-listed proposers prior to the submission of technical and price proposals, as this encourages the open and candid exchange of concepts, concerns, and ideas.

- Owners should protect the intellectual property of all proposers and should not disclose such information during the proposal process.

- Owners should offer a reasonable stipend to unsuccessful short-listed proposers when the proposal preparation requires a significant level of effort.

- Owners should ensure that their technical and cost proposal evaluation team members are (a) trained in the particulars of the procurement process, (b) unbiased, and (c) undertake their reviews and evaluations in a manner consistent with the philosophy and methodology described in the procurement documents.

- Owners should ensure that technical review teams do not have access to financial/price proposals until after completion of the scoring of the technical proposals.

- Owners should provide unsuccessful proposers with an opportunity to participate in an informative debriefing session.

3.8 FAA Procurement Requirements

Projects that receive grant funding under FAA’s AIP and are delivered through alternative PDMs are subject to certain requirements:

- FAA’s guidance is contained in Appendix G of AC 150/5100.14E: Architectural, Engineering, and Planning Consultant Services for Airport Grant Projects (FAA 2014).

- Additionally, FAA’s Airport Improvement Program Handbook (Order 5100.38D, Change 1), hereafter referred to as the “Handbook,” provides the guidance and policies for the administration of the AIP (FAA 2019).

Appendix G of AC 150/5100.14E provides high-level requirements relative to the procurement process for DB and CMAR. Among the procurement requirements are the following (FAA 2014):

- Documentation that the selection process is allowed under state or local law;

- An organizational chart that shows contractual relationships between all the parties;

- A statement describing what safeguards are in place to prevent conflicts of interest;

- Documentation that the system will be as open, fair, and objective as the traditional DBB project delivery system; and

- Documentation of the amount of experience the parties involved in the project have in the proposed project delivery method.

Appendix G of AC 150/5100.14E also notes that certain characteristics of alternative PDM projects are not allowed under the AIP, including

- Early completion bonuses,

- Cost overruns greater than 15%,

- Shared cost savings, and

- Price escalation.

Appendix G of AC 150/5100.14E provides guidance on how to procure both DB and CMAR projects. This is consistent with the guidance discussed in Section 3.4.3 for best value CMAR and DB projects:

- DB. A two-step process “can” be used, when a short list of at least three entities submits proposals. Technical proposals that include “preliminary drawings, outline specifications, and project schedules” are evaluated first. These are evaluated on a “numerical points earned system” (i.e., weighted criteria) basis. Price proposals are then opened and factored into the points earned system to decide the final selection, consistent with the weighted criteria approach.

- CMAR. A two-step process “is” used, in which a short list is developed. While Appendix G does not provide a requirement for the number of CMAR short-listed proposers, the Handbook notes that two or more are expected. The short-listed firms in the second step provide price information for such items as “profit/contractor fee, insurance, bonding and general conditions.”

The requirements for DB and CMAR contracts are covered in the Handbook, Appendix U, “Sponsor Procurement Requirement,” Paragraph U-16, which quotes directly from 2 CFR § 200.320(d), “Procurement by Competitive Proposals”:

The technique of competitive proposals is normally conducted with more than one source submitting an offer, and either a fixed-price or cost-reimbursement type contract is awarded. It is generally used when conditions are not appropriate for the use of sealed bids. If this method is used, the following requirements apply:

- Requests for proposals must be publicized and identify all evaluation factors and their relative importance. Any response to publicized requests for proposals must be considered to the maximum extent practical;

- Proposals must be solicited from an adequate number of qualified sources;

- The non-federal entity must have a written method for conducting technical evaluations of the proposals received and for selecting recipients;

- Contracts must be awarded to the responsible firm whose proposal is most advantageous to the program, with price and other factors considered; and

- The non-federal entity may use competitive proposal procedures for qualifications-based procurement of architectural/engineering (A/E) professional services whereby competitors’ qualifications are evaluated, and the most qualified competitor is selected, subject to negotiation of fair and reasonable compensation. The method, where price is not used as a selection factor, can only be used in procurement of A/E professional services. It cannot be used to purchase other types of services though A/E firms are a potential source to perform the proposed effort.

Table U-9 of the Handbook provides clarifications to Paragraph U-16 and explains that DB and CMAR can be procured through a competitive proposal process (i.e., one in which the owner awards on the basis of price or other factors) if the owner determines that sealed bids cannot be used. Sealed bids are to be used when the owner awards principally on the basis of price. Table U-9 provides guidance on this by giving examples of situations in which competitive proposals may be appropriate. These examples include “complex terminal projects (where there are multiple methods of construction and phasing), large demolition projects (where there are multiple methods of demolition), and rehabilitation of runway crossings (where contract time, phasing, or method may have added benefits).”

Table U-9 provides further guidance on the use of competitive proposals for DB and CMAR, including the following:

- Both methods can be conducted by either a one-step or a two-step process.

- An adequate number of qualified sources (i.e., the number of proposers) for CMAR is considered to be two; for DB, three or more are required.

- The owner must have a written basis for selection prior to receipt of proposals.

- Price must be a factor for DB and CMAR procurements.

Table U-9 also prescribes some technical requirements that must be met with regard to procurement, including the following documentation:

- The reasons and justification as to why competitive proposals were used over sealed bids;

- Documentation that the selection process is allowed under state or local law;

- Proof that the system will be as open, fair, and objective as the traditional sealed bid method; and

- Demonstration of the amount of experience of the parties involved in the project with the proposed procurement method.

Taken as a whole, FAA’s views on the procurement of CMAR and DB are largely consistent with what industry has used for these delivery systems. Perhaps the most important points to note are that an owner that will be subject to these requirements will first have to decide that the use of competitive proposals, versus sealed bids, is appropriate. Assuming the owner does so, the key to procurement success will be to ensure that the following have been clearly identified:

- The nonprice factors that are most important to the project’s success,

- The relative weights of these nonprice factors, and

- The relative weight of price and the nonprice factors.

3.9 Considerations in Selecting a Procurement Method

In summary of the information presented in this chapter, Table 3-1 presents the attributes of and challenges to implementation associated with the main procurement methods used in airport construction (i.e., low bid, QBS, and best value), and the PDMs with which they are commonly used.

Table 3-1. Comparison of procurement methods.

| Low Bid | Qualifications-Based Selection | Best Value |

|---|---|---|

| Potential Advantages | ||

|

|

|

| Challenges/Risks | ||

|

|

|

| When to Use? | ||

|

|

|