Selecting, Procuring, and Implementing Airport Capital Project Delivery Methods (2024)

Chapter: 2 Project Delivery Methods

CHAPTER 2

Project Delivery Methods

2.1 Introduction

The term “project delivery method” (PDM) refers to the comprehensive process used to execute and complete a capital project, including planning, programming, design, construction, and, potentially, operations and maintenance. Historically, public-sector construction entailed the almost exclusive use of the design–bid–build (DBB) delivery method, which involves the separation of design and construction services and the sequential performance of design and construction. However, over the past two decades, airports have increasingly been turning to alternative PDMs to improve the speed and efficiency of the project delivery process.

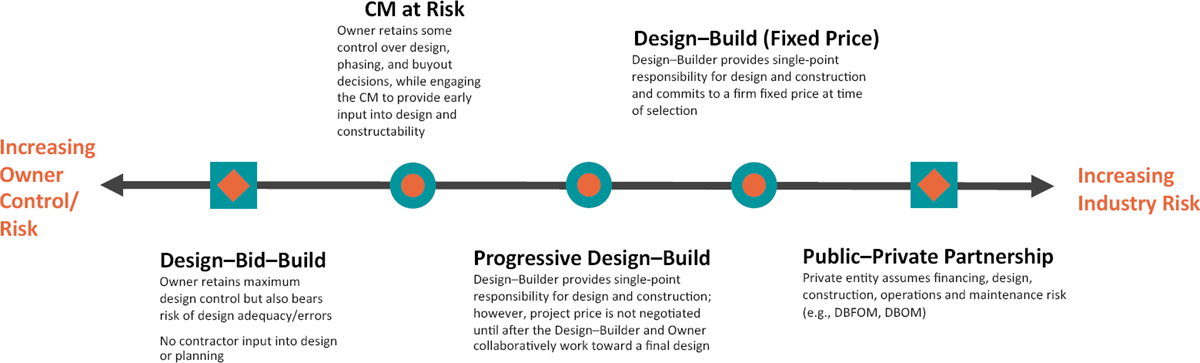

These alternative PDMs move closer to the integrated services approach to project delivery favored in the private sector. To illustrate this concept, Figure 2-1 shows the various PDMs used in airport construction arranged on a continuum, with the traditional DBB approach appearing on the left and the more alternative methods arranged from left to right according to the increase in responsibility and performance risk assumed by the airport’s industry partners. Each of the methods shown in Figure 2-1 has its own set of risks and rewards. Deciding when to use and how to implement a particular PDM is, therefore, critical to realizing successful project outcomes.

To deliver a project wisely, at the time of the PDM selection decision, project sponsors should have a clear understanding of the relative costs, benefits, and risks of the different PDMs available as well as the typical conditions under which these PDMs have been effectively applied. To this end, this chapter presents

- Key attributes of the different PDMs used to deliver airport capital projects, including those shown in Figure 2-1 as well as indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity (IDIQ), which is commonly used for maintenance and small or routine construction projects, and the less frequently used method of integrated project delivery (IPD);

- The perceived advantages and disadvantages of these PDMs; and

- The considerations driving airports to use different PDMs.

In addition, this chapter introduces an automated Excel-based decision support framework to assist users in evaluating and selecting suitable PDMs for their projects and documenting the rationale behind their decision-making (see Section 2.4.2).

2.2 Traditional Project Delivery (Design–Bid–Build)

2.2.1 Overview

DBB is the traditional PDM for public-sector construction projects. Under this method, which continues to be highly used today, the owner (or its consultant) prepares complete design

Note: Different PDMs are generally distinguished by how they approach the allocation of risk and responsibility among the owner, the designer, and the builder. The owner has maximum control and risk under the DBB approach. Industry involvement and performance risk increase from left to right along the continuum. CM = construction manager; DBFOM = design–build–finance–operate–maintain; DBOM = design–build–operate–maintain.

documents prior to putting the project out to bid. A contractor is then selected, typically on a lowest price basis, to construct the designer’s completed plans.

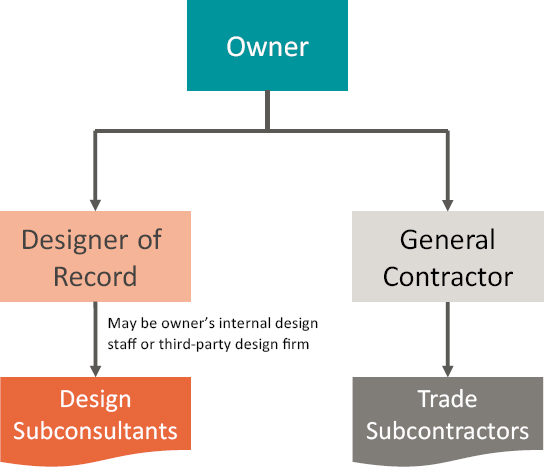

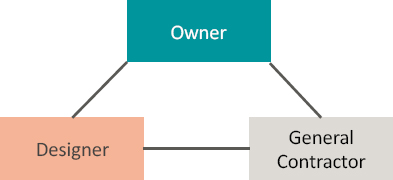

As shown in Figure 2-2, a defining feature of DBB delivery is the separation of design and construction services. The owner largely retains control of project design and, thus, the risk and financial responsibility for design errors or omissions encountered by the contractor.

2.2.2 DBB Advantages and Disadvantages

Over the years, conventional DBB delivery, along with the low bid procurement system with which it is generally intertwined, has served owners reasonably well, providing adequate facilities at the lowest initial price that responsible, competitive bidders may offer. While awarding to the lowest bidder provides no guarantee that the owner will receive the final lowest price, it does

- Simplify the construction award process and provide confidence that favoritism did not play a role in the selection decision and

- Minimize the need for sophisticated price negotiation tactics and understanding of underlying market conditions.

In addition, the owner, having had full control over the design process, should be positioned to receive the exact end product that it desires.

However, as there is no contractor involvement in the design stage, the design may lack elements of constructability, which could potentially impact the cost or duration of the work or both. Furthermore, the separation of services under DBB has the potential to create adversarial relationships among the project participants that the owner will then have to referee. Table 2-1 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages related to DBB.

Airports with the flexibility to use a wide range of PDMs generally reported using DBB on smaller projects, such as runways, roadways, substations, and a variety of state-of-good-repair projects, particularly if funded, in whole or in part, by FAA’s Airport Improvement Program (AIP).

2.2.3 Application

Traditional DBB lends itself to projects that satisfy the following criteria:

- The project, from initial concept through the end of construction, is not time driven. (This is because, under DBB, the design and construction phases do not overlap.)

Table 2-1. DBB advantages and disadvantages.

| DBB Advantages | DBB Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

- The owner knows exactly what it wants and can specify what it wants.

- The work is unlikely to experience significant change (e.g., due to changing stakeholder needs or preferences, unforeseen conditions).

- The owner is in the best position to manage third-party risks.

2.3 Alternative Delivery Methods

Conventional DBB will always have a place in an owner’s project delivery toolbox, and it is not the intent of this guide to suggest otherwise. However, alternative methods may offer potential rewards in terms of enhanced cost, time, or quality performance, if used under the right circumstances.

To appreciate the circumstances or conditions that would drive one to consider an alternative PDM, it is important to first understand the unique attributes of each. This section describes key characteristics as well as the potential advantages and disadvantages of the different alternative PDMs commonly used to deliver airport capital construction projects.

2.3.1 Construction Manager at Risk

Overview

The construction manager at risk (CMAR) delivery method, also commonly referred to as “construction manager/general contractor” (CM/GC) and “general contractor/construction manager” (GC/CM), attempts to shift more control and risk to industry (though to a lesser extent than design–build (DB) delivery, as discussed in Section 2.3.2).

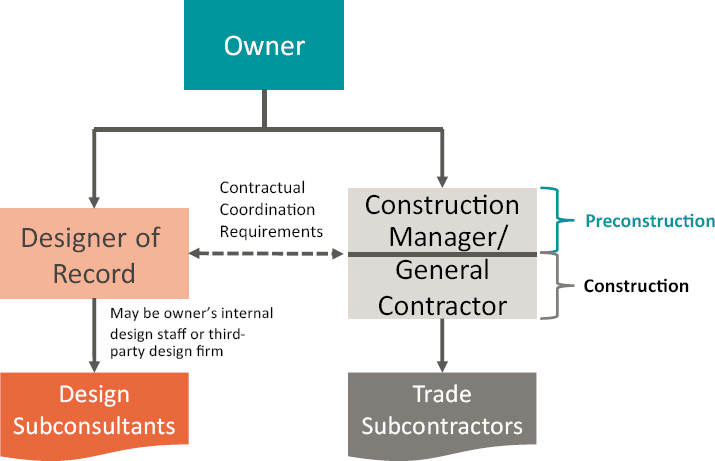

As depicted in Figure 2-3, under the CMAR approach—similar to DBB—the owner holds separate contracts with the designer and the construction manager (CM). However, a key difference between DBB and CMAR is the timing of the CM’s selection. In CMAR, the CM is selected prior to the completion of the design (ideally before the 15% design stage), which allows the CM to participate in the design development process via a preconstruction services agreement. The selection of the CM generally takes the form of a either a pure qualifications-based selection (QBS) or a one- or two-step best value approach, as discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3.

Table A-2 in Appendix A presents a one-page overview of the CMAR delivery method.

The preconstruction services provided by the CM typically involve providing input to the owner and design team regarding constructability, scheduling, pricing, phasing, and risk management (see Box 2-1). When the project scope is sufficiently defined, the owner and contractor negotiate a price for the construction phase of the project, during which the CM acts as the general contractor (GC), holding the trade contracts, managing the construction of the work, and assuming performance risk for cost, schedule, and quality.

Box 2-1. Typical Preconstruction Services Requested of the CM

Conducting technical design and constructability reviews to

- Identify challenges with the design, with the intent of improving the constructability and economy of the project;

- Assess the feasibility and practicality of the selected materials and equipment as well as the availability of material, labor, and equipment;

- Assess site/access constraints and potential impacts to construction phasing and manpower restrictions; and

- Confirm all work has been included in the construction documents and described in sufficient detail to ensure complete pricing.

Supporting the design development process by

- Assisting with the designer’s investigations of existing conditions as needed (e.g., opening concealed areas, test pits);

- Providing real-time estimating support to the designer to help guide design development activities and the selection of the optimal design alternatives;

- Identifying the schedule impacts/benefits of different design alternatives and ways to mitigate potential delays (e.g., advance purchasing of long-lead materials and equipment); and

- Developing, in consultation with the designer, a detailed scope of work, schedule, and estimate.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Although use of the CMAR approach will not eliminate the potential for adversarial disputes to arise between the parties, the early involvement of the CM should help foster a more collaborative and integrated team approach to problem-solving, particularly if CMAR is implemented with some of the collaborative design and construction techniques discussed in Section 5.4.

In addition, early collaboration with the CM during the design phase can be used to help establish design priorities, identify prefabrication opportunities, provide pricing for design alternates, and establish strategies for overcoming or mitigating potential construction risks. The earlier such input and ideas are obtained, the more seamlessly they can be incorporated into the final design solution.

A summary of additional advantages and disadvantages associated with CMAR is provided in Table 2-2.

Application

CMAR delivery lends itself to projects that would benefit from the collaborative involvement of the owner, designer, and CM to optimize design and construction activities and to resolve the potential problems that may arise during construction. This includes projects with

- A high potential for unknown or poorly defined risks;

- Complex phasing or staging to mitigate impacts to operations or the traveling public; and

- Designs that are complex, difficult to define, or subject to change.

2.3.2 Design–Build (Fixed Price)

Overview

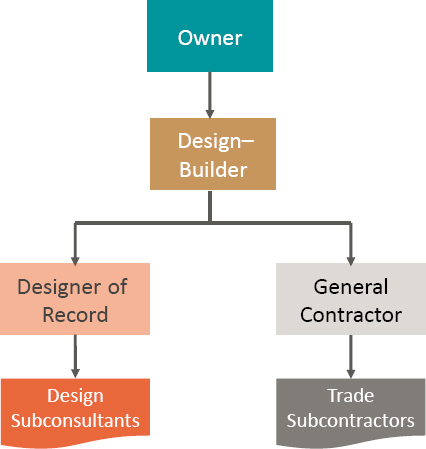

Under the design–build (DB) delivery method, a single entity is responsible for both the design and construction of a project. This integration of design and construction services under one contract supports

- Earlier cost and schedule certainty,

- Closer coordination of design and construction, and

- A nonsequential delivery process that allows for construction to proceed before completion of the final design.

49 USC § 47142 establishes DB as an approved form of contracting under the AIP.

As shown in Figure 2-4, DB delivery is characterized by a single contract between the owner and a DB entity responsible for providing both design and construction services. As the use of DB has evolved, it has taken on organizational variations that may involve joint ventures or other teaming arrangements involving several firms. In the airport sector, DB is commonly led by a GC as the prime with an architectural/engineering firm as a subcontractor.

Table A-3 in Appendix A presents a one-page overview of the DB (fixed price) delivery method.

Traditionally, the design–builder has assumed responsibility for delivering the design and construction of the work according to the fixed price (and schedule) offered in its proposal. Over the years, as summarized in Table 2-3, other DB variants have emerged to improve or optimize the delivery process on the basis of project type or characteristics. However, the predominant approach for airport construction remains the more classic fixed-price DB variant, with the design–builder selected using a best value procurement process. This is particularly true for airports that must encumber project funds on the basis of defined revenue constraints that better align with lump-sum contracts.

Advantages and Disadvantages

With DB, the owner has a single point of contact for the design and construction of the project. This centralized responsibility in large part allows the owner to avoid the effects of the Spearin

Table 2-2. CMAR advantages and disadvantages.

| CMAR Advantages | CMAR Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

doctrine [United States v. Spearin, 248 U.S. 132 (1918)], which places the risk of a defective design on the owner. Use of DB can thus reduce project disputes, as compared with a DBB or even a CMAR project, in which a separate designer and builder may ultimately clash over whether a project issue stems from a poor design or the contractor’s execution of that design. Regarding change management, it should also be noted that the quality of the owner’s solicitation and project definition documents are of critical importance to ensuring successful project outcomes. If the solicitation documents fail to properly reflect what the owner wants or will accept, the resulting change orders can be costly, especially if any redesign is required.

Empirical studies from the past 20 years that compare DBB with DB across multiple construction sectors have shown that use of DB can provide time and, to some extent, cost savings.

Table 2-3. DB variants used in airport construction.

| Approach | Application | Procurement Process a | Contract Typeb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional DB (fixed-price agreement + best value selection) | Larger, more complex projects in which innovation is sought and the owner believes that considering factors other than price is beneficial when selecting a design–builder | One- or two-step best value process with selection based on price and technical factors | Lump sum |

| Low bid DB | Smaller, less-complex, and low-risk projects having clearly defined scopes of work (for which the owner deems it unnecessary to differentiate proposers on the basis of technical approach) | One- or two-step process with selection based on the lowest price | Lump sum |

| DB fixed-price–maximum scope | A cost-control strategy (typically used on smaller, less-complex, and low-risk projects having clearly defined scopes of work) in which the competition is based on the maximum scope proposers will offer for a defined budget ceiling | Selection based on base bid with options not to exceed the stipulated budget and representing the best value to the owner | Lump sum with additive or deductive options |

| Progressive DB (See Section 2.3.3 for more details regarding this DB variant.) | Projects for which the owner desires a design–builder’s input into program development and preliminary design before a firm contract price is established | One- or two-step process with selection based on either pure qualifications/technical approach or best value | Typically, a preliminary services agreement followed by a lump-sum final design and construction agreement |

| DB with finance, maintenance, and/or operations (See Section 2.3.4 for more details regarding such public–private partnership arrangements.) | Large or mega projects for which the owner may lack the financial capacity to execute the project or projects beyond the owner’s core mission that can generate revenue (e.g., consolidated rental car facilities) | Competitive negotiations | Various contracting approaches (e.g., payments based on postconstruction project revenues, availability payments, or management fees) |

a See Chapter 3 of this guide for more details on the procurement approaches used to select providers of airport construction services.

b See Chapter 4 of this guide for more details on the contracting types and payment mechanisms used for airport construction projects.

For example, a 2005 study comparing DB highway projects with comparable DBB projects found that use of DB resulted in significant time savings and, to a lesser extent, cost savings (FHWA 2006). On average, the managers of DB projects surveyed in the study estimated that DB project delivery reduced the overall duration of their projects by 14%, reduced the total cost of the projects by 3%, and maintained the same level of quality as compared with DBB project delivery. The project survey results revealed that, as compared with DBB, DB project delivery had a mixed impact on project cost, depending on the type, complexity, and size of the project.

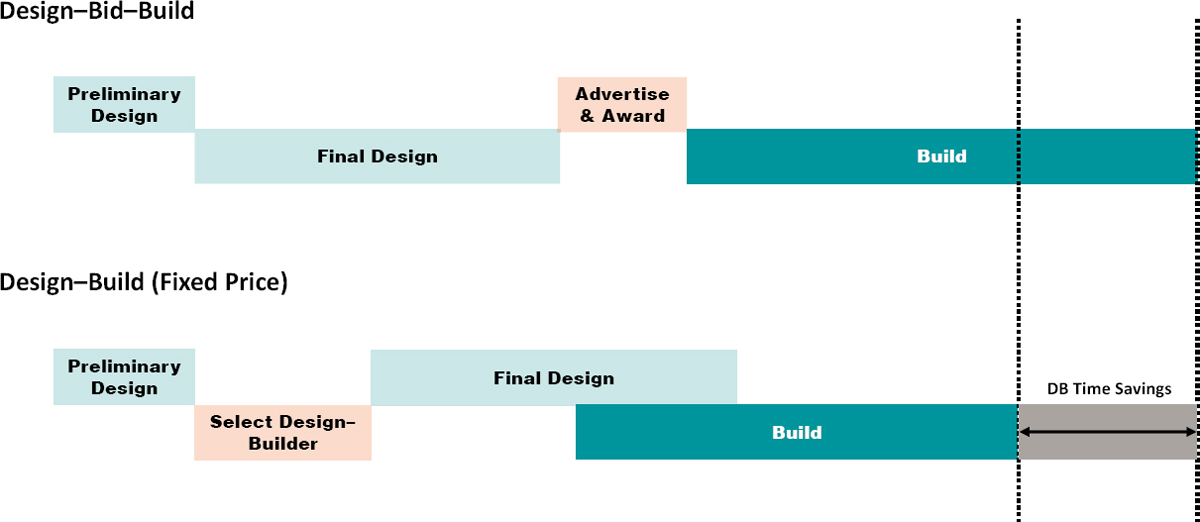

With regard to time savings, as compared with DBB, overall project durations tend to be reduced under DB, even considering the lengthier and more resource-intensive DB procurement process, because construction often proceeds before the design is complete and at a faster pace. A conceptual comparison of the sequence of project delivery demonstrating such time savings is shown in Figure 2-5.

It is important to note that the advantages of DB are generally only realized when a careful and well-informed approach is taken to project selection, procurement, contracting, and oversight. Likewise, some of the identified disadvantages may be averted or mitigated to some extent through similar means.

A summary of the advantages and disadvantages associated with DB is provided in Table 2-4.

Table 2-4. DB (fixed price) advantages and disadvantages.

| DB Advantages | DB Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

Application

DB delivery is most beneficial under the following circumstances:

- The owner knows what it wants and can specify what it wants in a clear, unambiguous manner without 100% complete plans, specifications, and estimates.

- The project is unlikely to experience significant changes outside of the contractor’s control.

- The owner desires early price certainty or the date by which funding must be obligated will not allow for a complete design, or both.

- The project would benefit from an accelerated timeline.

- The project presents minimal third-party risks (or, alternatively, such risks can be effectively managed by the design–builder).

- Industry is better positioned to complete or manage the design process (e.g., as may be the case for projects involving proprietary equipment or systems, such as baggage screening and handling systems).

DB can also be an effective option to support the rehabilitation or replacement of isolated assets for state of good repair. For example, bundling multiple small projects (e.g., runway lighting or various internal repairs to the terminal facility) under a single DB contract can allow for faster completion of such work and could possibly promote innovative solutions. One airport expressed satisfaction with using DB in this manner to support improvements needed to adhere to current standards of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Performing this work as a DB project created synergies across projects, placed accountability upon a single project team to adhere to the standards, and facilitated the airport’s monitoring of its ADA transition plan.

2.3.3 Progressive Design–Build

Overview

Progressive design–build (PDB) is a variation of DB in which the design–builder is engaged early in the project development process, typically through a preconstruction services contract, and then collaborates with the owner to validate the basis of design and to advance, or progress, toward a final design and associated contract price.

Table A-4 in Appendix A presents a one-page overview of the PDB delivery method.

The basic PDB contractual structure is comparable to that shown in Figure 2-4 for the more conventional fixed-price variant of DB discussed in Section 2.3.2 (that is, the design–builder provides a single point of responsibility for design and construction services). However, under PDB, the design–builder typically delivers the project in the following two phases (for which two separate contracts may be executed):

- Phase 1 (preliminary or preconstruction services), including confirmation of the owner’s program, development of the preliminary design, and negotiation of a firm contract price for Phase 2; and

- Phase 2, including the final design, construction, and commissioning.

Advantages and Disadvantages

In contrast to the fixed-price variant of DB discussed in Section 2.3.2, under the PDB approach, no cost certainty is provided at the time of the design–builder’s selection; the project price is instead negotiated following the design–builder’s involvement in design development and preconstruction activities. (See Box 4-1 in Chapter 4 for sample contract language from the Nashville International Airport addressing the progressive establishment of a guaranteed maximum price for the cost of the work.)

The direct contractual relationship between the designer and contractor under a PDB approach provides the primary means of distinguishing PDB from CMAR. This single point of responsibility can be beneficial for projects with major risks that would benefit from minimizing the potential for adversarial disputes and change orders related to “errors and omissions.”

This delayed establishment of a project price provides flexibility (similar to the CMAR approach) for the parties to adjust the project’s final scope to suit the owner’s budget or schedule constraints as new information becomes available (e.g., existing conditions or geotechnical information discovered after the selection of the design–builder) or in response to late stakeholder requests or changing market conditions.

Likewise, the ongoing involvement of the design–builder in the development and design of the project should help promote more realistic pricing assumptions and thus help reduce risk in the project in a manner that may allow for a reduction in contingency pricing (in contrast to the traditional DB approach, in which the project price is established before the design has been advanced to a point where contingencies for scope and quantity growth can be minimized).

In addition, by the time the construction phase price is established, the owner will have had more input into, and better understanding of, the appearance, functionality, material selection, and

whole-life costs of the facility the design–builder will be constructing. The likelihood of preferential owner changes once a final construction cost is negotiated are thus greatly reduced, increasing the cost certainty of construction phase services. If changes still occur once construction is underway, the owner will have increased insight into the design–builder’s cost base, as a result of the preconstruction phase estimating and cost negotiation process. A summary of the advantages and disadvantages associated with PDB is provided in Table 2-5.

Application

With regard to the early selection of a design–builder and the subsequent negotiation of a construction price once the design has been sufficiently advanced, PDB is far more similar to CMAR than to fixed-price DB. In fact, the primary difference between these methods is that the PDB entity will provide a single source of accountability for both the design and construction of the work. This distinction can be beneficial for projects with major risks that can best be mitigated by having the contractor and designer in a direct contractual relationship, thus minimizing the potential for adversarial disputes and change orders and claims related to “errors and omissions.”

2.3.4 Public–Private Partnerships

Overview

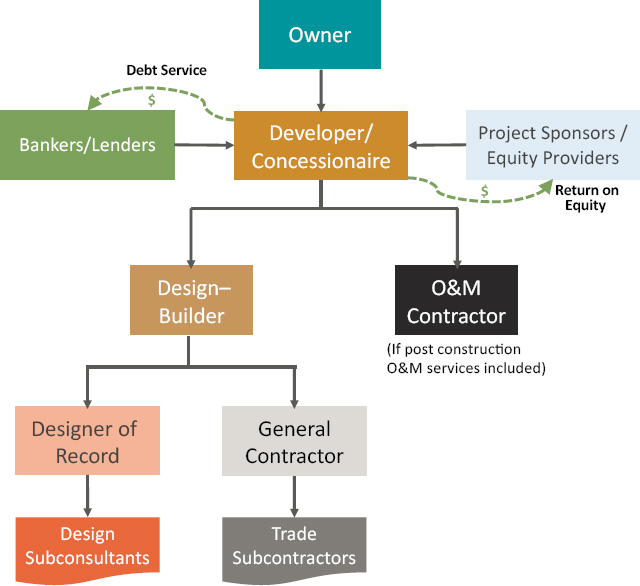

A public–private partnership (P3) agreement centralizes project delivery under a single contract with one private entity (which may involve a consortium of multiple firms) to assume responsibility for the design, construction, operations, maintenance, and/or financing of a public facility (Figure 2-6).

ACRP Research Report 227: Evaluating and Implementing Airport Privatization and Public-Private Partnerships (Wolinetz et al. 2021) offers a more in-depth discussion of the use of P3s for airports, including best practices and lessons learned.

The structure under which the private-sector participant is to design, build, finance, operate, and/or maintain the facility depends largely on the owner’s priorities regarding overall cash outlay; the timing of the owner’s monetary obligations, performance needs, short- and long-term

Table 2-5. PDB advantages and disadvantages.

| PDB Advantages | PDB Disadvantages |

|---|---|

In addition to the advantages identified in Table 2-4 for design–build (fixed price), progressive DB

|

|

risk allocation (for both operational and financial performance); and resource availability. Common P3 structures include the following:

- Design–build–finance (DBF) combines traditional DB delivery with some amount of private-sector capital (typically to fill gaps in funding and allow projects to be built faster).

- Design–build–operate–maintain (DBOM) combines the design and construction responsibilities of DB contracts with operations and maintenance responsibility for the private partner.

- Design–build–finance–maintain (DBFM) is similar to the DBF approach, but the private partner also assumes short- to medium-term operational responsibility. Unlike DBOM, however, the owner retains responsibility for operations.

- Design–build–finance–operate–maintain (DBFOM) is similar to the DBOM approach, but the private partner also assumes responsibility for financing.

Advantages and Disadvantages

P3 agreements are often seen as a recourse to addressing budget constraints or financing gaps, particularly for owners that wish to execute large-scale capital projects requiring access to significant equity investment. For owners that otherwise have the financial capacity and investment–grade credit ratings to pursue such projects on their own, P3s can provide an effective option for efficiently delivering projects that are outside of the owner’s core mission and for which the owner lacks the staff expertise to operate and maintain the asset (e.g., consolidated rental car facilities, automated people movers).

Table A-5 in Appendix A presents a one-page overview of the P3 delivery method.

P3s can also allow airports with high costs per enplaned passenger to deliver projects off balance sheet through availability payments or service agreements and thus allow the airport to avoid adding debt to its balance sheet. Table 2-6 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages associated with P3s. For a more thorough understanding of the P3 delivery model, readers may consult ACRP Research Report 227: Evaluating and Implementing Airport Privatization and Public-Private Partnerships (Wolinetz et al. 2021).

Table 2-6. P3 advantages and disadvantages.

| P3 Advantages | P3 Disadvantages |

|---|---|

For P3 projects with operations and maintenance components:

For P3 projects with a finance component:

|

|

Application

When considering a P3, owners should

- Conduct a value-for-money analysis to compare the projected costs of possible P3 structures against more traditional delivery options;

- Consider risk allocation, including how to secure the private partner’s performance, not only during design and construction, but over the long-term operations period; and

- Evaluate in-house resources and whether the owner has the necessary in-house team to deliver and operate the facility, or if it would be more efficient and cost-effective for the project to be delivered and operated by the private sector.

2.3.5 Integrated Project Delivery

Overview

In a formal IPD agreement, the owner, designer, and general contractor all sign a joint agreement that binds the success of each party to the success of the project (Figure 2-7). Typical characteristics of such multiparty agreements include the following:

- The members of the project team jointly develop and agree to project goals and a target cost.

- At project completion, the target cost is then compared with the final cost, and the underruns or overruns are shared equitably (through previously agreed ratios) among the participants according to their relative contributions to the leadership, performance, outcomes, and overall success of the project. In this manner, all participants have a financial stake in the project’s overall performance.

- Project risk and responsibilities are shared and managed collectively rather than allocated to specific parties.

- All participants have a say in decisions for the project, with decisions being made on a best-for-project basis rather than to further individual interests.

- All participants provide best-in-class resources. Full access is provided to the resources, skills, and expertise of all participants.

- The agreement creates a no-fault, no-blame, and no-dispute culture in which no legal recourse exists except for the limited case of willful default and insolvency.

- All transactions are open book.

Such multiparty IPD agreements are rare in airport construction. However, even without a formal IPD agreement, certain collaborative implementation techniques can be used with any of the alternative PDMs discussed in Section 2.3 to drive project participants to act more as an integrated team. Practices aimed at modifying traditional behavior and promoting partnering and collaboration are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5, Section 5.4, of this guide and include the following:

- Use of collaborative partnering techniques,

- Use of building information modeling as a platform for collaboration throughout the project’s design and construction phases, and

- Use of lean design and construction tools to support collaborative planning and problem-solving.

Advantages and Disadvantages

The fostering of a more integrated team approach can increase the efficiency of project delivery, create a less adversarial system, and promote more proactive risk management. To realize such benefits, however, requires a high level of involvement from senior leaders within the owner’s organization. This is because IPD tends to be an owner-driven process that starts with establishing clear expectations regarding what the IPD team is to achieve for the project to be considered a success. As the project proceeds, the owner must then remain committed to serving as a fully engaged and knowledgeable participant in the project, actively working to ensure that the team is tracking to the project success criteria while largely relinquishing the ability to make unilateral changes. The advantages and disadvantages of IPD agreements are summarized in Table 2-7.

Application

IPD agreements lend themselves to complex, high-risk projects in which risks are unpredictable, inherent to the nature of the work (rather than due to inadequate planning, scoping, or time), and best managed collectively. The project should also derive significant benefit from the

Table 2-7. IPD advantages and disadvantages.

| IPD Advantages | IPD Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

Table 2-8. IDIQ advantages and disadvantages.

| IDIQ Advantages | IDIQ Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

involvement of both the owner and nonowner participants in all aspects of project development and implementation.

2.3.6 Indefinite Delivery, Indefinite Quantity

IDIQ contracts (also called job order contracts, on-call contracts, or master contracts) provide a delivery option for relatively small construction and maintenance projects that consist of clearly defined, standardized, or repetitive work items. (As the focus of this guide is primarily on larger capital construction projects, for which IDIQ is of limited use, this method is presented here only in brief.)

Under the IDIQ approach, an owner selects a firm (typically on the basis of qualifications and a proposed markup fee) to perform an indefinite quantity of work over a set time period using work orders that are priced on the basis of unit price books and a fixed markup fee. Engaging contractors through IDIQ work orders can significantly reduce a project’s lead time and cost by eliminating the potentially time-consuming and costly aspects of traditional bidding procedures. The advantages and disadvantages of IDIQ contracts are summarized in Table 2-8.

For small construction or maintenance projects, IDIQ contracts provide owners with ready access to qualified, on-call contractor(s) who are familiar with the owner’s organization, needs, and facilities.

2.4 PDM Selection Considerations

No single delivery method is appropriate for all projects and situations. As discussed earlier in Sections 2.2 and 2.3, all PDMs hold unique advantages and disadvantages that should be weighed carefully when how to best deliver a particular project is being considered.

For a given project, a key early decision in the project development process is selecting the optimal delivery approach based on project’s characteristics, goals, risks, and constraints. To this end, this section summarizes the typical criteria used to select a PDM for a project, as based on a review of the literature and the experience of the airports interviewed as part of the development of this guide. An automated Excel-based PDM selection tool developed in conjunction with this guide is also introduced. The selection considerations discussed here and the associated tool focus on the PDMs most frequently implemented for airport capital construction (i.e., DBB, CMAR, DB, and PDB). For selection considerations regarding P3s, readers are referred to ACRP Research Report 227 (Wolinetz et al. 2021).

2.4.1 Selection Criteria

The PDM that will best suit a particular project can depend upon a range of factors, including legislative constraints, project goals, financial considerations, project characteristics, and the state of the construction market. Examples of such considerations are summarized below.

Legislative Constraints

Some airports are subject to strict statutory language governing the legal environment for implementing alternative PDMs. Such prescription has often been developed in response to stakeholder concerns related to competition, professional licensure, stipends, participation plans regarding disadvantaged business enterprises (DBEs), and other local circumstances. In some cases, this has resulted in limits on the project size threshold, the project type, or the number of projects allowed to be delivered with a particular alternative PDM. For example, under Massachusetts General Laws (MGL), Chapter 149A, the Massachusetts Port Authority may use CMAR for vertical building projects over $5 million and DB for horizontal (civil works) projects that exceed $5 million. Prescriptive requirements may also extend to key aspects of the PDM procurement process, including the contents of solicitation documents, proposal evaluation criteria, makeup of the proposal evaluation committees, and the award process.

As an initial consideration, the owner should become familiar with any legislative constraints that could limit the use of a particular PDM.

Project Delivery Goals

When the PDM to be used on a particular project is being considered, a good starting point is prioritizing the owner’s project delivery goals (e.g., accelerated schedule, early cost certainty, innovation), as some methods are more likely to advance certain goals than others. On the basis of the literature review conducted for this project and the experience of the researchers and of the practitioners who were interviewed, the following common project delivery goals were identified: schedule, project cost, design flexibility, owner control, and risk management. These are addressed in the following discussion, along with the perceived advantages and challenges posed by implementing different PDMs in the context of these goals.

Schedule.

The choice of PDM can have a significant impact on the overall project schedule, from scoping through design and on to construction and completion. As compared with the duration of a DBB project, the overall project duration under a PDM that allows for early contractor involvement tends to be reduced, because detailed design can often overlap with construction. Such fast-tracking potential is a commonly cited advantage of fixed-price DB.

CMAR and PDB also offer the potential to reduce the overall project delivery schedule, as neither method requires the owner to fully define the project’s scope of work prior to engaging the CM or design–builder. (In PDB it is common to bring on the design–builder at the start of programming or preliminary design; in CMAR, the CM is typically engaged a bit later, at approximately 15% design.) This early involvement can generate time savings, even though these methods, as compared with fixed-price DB, tend to promote a higher level of stakeholder collaboration and a more iterative, consensus-driven design process that can prolong the design phase. Several airports that used CMAR or PDB reported taking the design of individual work packages to 100% to allow for competitive bidding of trade work (typically to comply with the governing procurement code or internal policies). In such cases, the potential to fast-track construction under CMAR and PDB is often limited to early work or enabling packages. A conceptual comparison of the sequence of project delivery for different PDMs that demonstrates such potential time savings is shown in Figure 2-8. The schedule-related considerations of implementing different PDMs are summarized in Table 2-9.

To arrive at the optimal PDM for a project, it is important to identify not only specific project delivery goals but also the relative importance of each, as trade-offs may be necessary between cost, schedule, and other project priorities.

Project Cost.

Potential cost-related goals for a project could include the following:

- Obtaining the lowest initial price competitive bidders can offer, as is the case with DBB;

- Obtaining early cost certainty, as is the case with fixed-price DB;

- Reducing risk premiums and enhancing overall cost certainty, as can be achieved under CMAR and PDB through the collaborative design development process and evaluation of priced design alternatives; and

- Minimizing cost overruns resulting from change orders, which can be achieved through DB (as the design–builder is responsible for design errors) and potentially through the more collaborative CMAR and PDB methods, given the time spent on reaching a consensus design solution and reducing risk in the project before establishing a construction price.

That the ideal PDM may differ according to specific project goals underscores the importance not only of identifying delivery goals, but also of assessing the relative importance of each. Trade-offs between different cost-related goals as well as schedule, innovation, and other possible project priorities will likely be necessary before arriving at the optimal PDM. The cost-related considerations of implementing different PDMs are summarized in Table 2-10.

Design Flexibility Versus Owner Control.

Airport capital construction projects can be challenging, as they tend to involve a multitude of external and internal stakeholders, legacy facilities and systems, and operational and security constraints, among other potential design and construction complexities.

In some cases, such complexities can be best addressed by the owner directly, particularly if only one specific solution would be acceptable. In such instances, the DBB method, which would provide the owner with complete control over the design and project phasing, may represent the optimal delivery option.

Other project scenarios may call for increased contractor involvement in the design process. For example, the more collaborative design development process promoted under CMAR and PDB can provide owners with priced alternatives to assist with decision-making as well as

Table 2-9. Schedule-related considerations of PDM implementation.

| Design–Bid–Build | Design–Build (fixed price) | Construction Manager at Risk | Progressive Design–Build |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential Advantages | |||

|

|

|

|

| Potential Challenges | |||

|

|

|

|

the flexibility to adjust the final project scope (and budget and schedule) as new information becomes available during the design process.

If the owner instead seeks innovative ideas from industry, fixed-price DB may present the best delivery option, as this method allows proposers to compete on the basis of design solutions during the procurement process, and the selected design–builder may then further optimize the final design to enhance constructability and innovation. The design-related considerations of implementing different PDMs are summarized in Table 2-11.

Risk Management.

The various PDMs offer differing approaches to risk management and allocation. As summarized in Table 2-12, the DBB approach can be beneficial when risks are best managed by the owner. If the owner instead desires to transfer the risk of project execution

Table 2-10. Cost-related considerations of PDM implementation.

| Design–Bid–Build | Design–Build (fixed price) | Construction Manager at Risk | Progressive Design–Build |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential Advantages | |||

|

|

|

|

| Potential Challenges | |||

|

|

|

|

to industry (e.g., to meet project cost, schedule, or other performance objectives), and accepts that it will likely incur an associated risk premium in doing so, fixed-price DB may provide a better approach.

Through the more collaborative CMAR and PDB approaches, the parties can collectively assess risks, identify the need to perform additional site investigations to further identify and reduce risks, and negotiate risk allocation prior to establishing a construction phase price. However, such negotiations may result in shifting the cost risk back to the owner.

Financial Considerations

To deliver their capital programs, airports rely on a mix of funding and financing sources, including debt financing, pay-as-you-go from existing revenue streams, grants, and cash reserves (see Box 2-2). The size and type of airport organization (e.g., city governed vs. independent aviation cost center, port cost center, maritime cost center) can drive the funding sources available. In turn, a project’s funding sources may play a role in the selection of the optimal PDM.

Timing and Availability of Funds.

At a high level, when the optimal PDM for a project is being determined, the most obvious financial planning consideration relates to when funds would be required. For example, owners will typically make payments to contractors on an ongoing basis (progress payments) as the project is being implemented under more traditional short-term PDMs. Alternatively, if a project is developed under an availability payment P3, the airport

Table 2-11. Design-related considerations of PDM implementation.

| Design–Bid–Build | Design–Build (fixed price) | Construction Manager at Risk | Progressive Design–Build |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential Advantages | |||

|

|

|

|

| Potential Challenges | |||

|

|

|

|

will only begin compensating the developer (in the form of periodic availability payments) after substantial completion. As such, the airport’s financial position could help determine what PDM it decides to pursue and which ones it cannot reasonably pursue. While this is mostly relevant when deciding whether to pursue a project as a P3, the timing of funds can also be a factor for more traditional short-term PDMs, such as DB, which can result in accelerated expenditures when design and construction services are fast-tracked. It is, therefore, important to consider the project’s anticipated cash flow needs and how such needs align with the airport’s overall revenue streams and likely project funding sources.

The team in charge of selecting a PDM should include, or at least consult with, representatives from the airport’s finance department to understand in advance the timing of such revenues and how and whether they could support a DB project. If a project’s cash flow needs may be at issue, but DB otherwise represents the optimal PDM, the owner may wish to present in the RFP the revenues available for each month (or year) of the project, so proposing teams can adjust their

Table 2-12. Risk management considerations of PDM implementation.

| Design–Bid–Build | Design–Build (fixed price) | Construction Manager at Risk | Progressive Design–Build |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential Advantages | |||

|

|

|

|

| Potential Challenges | |||

|

|

|

|

Box 2-2. Typical Funding Sources for Airport Capital Projects

Airport financing and funding typically consist of one or more of the following sources:

- Debt financing. The larger airports reported that they had investment-grade credit ratings and might choose to leverage future cash flows and issue debt to obtain the necessary upfront capital for a capital improvement project. In this context, airports can decide to finance a project on a nonrecourse basis (i.e., the debt is repaid from a dedicated revenue stream and debtors do not have recourse to any other airport revenues) or pledge airport-wide revenues and issue general airport revenue bonds (GARBs) (issued by the airport), or general obligation (GO) bonds (issued by the public owner of the airport). The exact financing structure and conditions depend on, among other things, the pledged revenue stream (including forecast and expected volatility), the desired maturity, the airport’s creditworthiness, and wider economic conditions. Airports may also leverage innovative financing solutions, such as subsidized loan programs from State Infrastructure Banks (SIBs) or loans through the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program, to lower a project’s overall cost of capital. Whereas the U.S. DOT has historically limited TIFIA loans to surface transportation facilities (e.g., parking

- garages, access roads, transit access facilities in the context of airports), the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act has expanded the definition of eligible projects to include airport-related projects [as defined in 49 USC § 40117(a)], which cover terminals, gates, noise compatibility measures, and conversion of service vehicles to low emission standards.

- Federal funding. There are different federal programs that airports can use to fund capital expansion projects, most importantly, FAA’s Airport Improvement Program (AIP). However, not all projects are eligible for AIP funding. Eligible projects include those related to enhancing airport safety, capacity, security, and environmental concerns. Typically, revenue-generating projects are not eligible. In addition to limitations in terms of eligibility, relying on federal funding may involve additional compliance requirements. To the extent that federal funding received requires the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) to be followed, the airport should ensure that its contracting approach allows for a sufficiently detailed level of reporting by the contractor so that it can comply with all requirements. Given that noncompliance could jeopardize funding, more traditional PDMs (e.g., DBB) may be preferable if the project is fully federally funded.

- State and local funding. Certain states provide funding for airport capital projects, often, but not always, in the form of matching funds for federal grants. Similar to federal funding, state and local funding may introduce a new level of compliance requirements. Furthermore, states or cities may seek a more active role, for example, by requiring the airport to obtain approval for project expenditure and involvement in reviewing contractors’ qualifications. Similar to federally funded projects, projects that receive state or local funding may benefit from more traditional PDMs (e.g., DBB) to reduce the risk of noncompliance or political issues.

- Passenger facility charges. Passenger facility charges (PFCs) are approved by FAA and can only be used for projects that “enhance safety, security, or capacity; reduce noise; or increase air carrier competition.” Airports can use these charges to contribute pay-as-you go funds to a capital project or, alternatively, issue bonds against future PFCs.

- Other airport-generated revenues. In addition to the federal, state, and local funding and FAA-approved PFCs, airports can use airport revenues for capital projects. These may include, among others, landing fees, terminal rents, apron and jetway charges, concessions, advertisement, parking fees, ground transportation fees, car rental fees—commonly used in funding consolidated rent-a-car (ConRAC) and rent-a-car multimodal facilities—hangar rentals, fuel charges, land leases, and more. As with PFCs, airports can use these revenues to contribute pay-as-you go funds to a capital project or, alternatively, issue bonds against them.

- Reserves. Airports can also use existing cash reserves to help fund a capital project.

approaches on the basis of their monthly estimate of costs. For example, slowing a DB project schedule may be required to accommodate the revenue sources available. It can also be beneficial, when negotiating and finalizing the DB contract, to ask for an estimated monthly expenditure curve based on the DB team’s schedule of design and construction activities.

Compliance Requirements Tied to Funding Sources.

When selecting a PDM, airports should also consider whether the anticipated funding source has compliance requirements that may have an impact on contract administration or project execution (e.g., Buy America provisions, DBE requirements). Given the constraints that may come with federal, state, and local funding as well as passenger facility charges (PFCs), airports may have more liberty in choosing a PDM when using airport-generated revenues or their own reserves.

Interviews with airports that were conducted to support the development of this guide indicated that specific sources of funding are often targeted for specific project types or PDMs. For example, when AIP block grants are included, the airports tend to apply AIP funding toward airfield capital improvements (e.g., runway pavements) or similar projects and use DBB or fixed-price DB delivery methods, in which pricing is fixed before funding authorization. Major terminal expansions that use CMAR or PDB delivery typically require more flexibility than AIP funding offers, so airports tend to use other sources of funding for such complex projects. Airlines can also have significant influence on major terminal improvements; they have provided financing for dedicated concourses and often work with airports on project scoping, design, and cost estimating for improvement projects.

The interviews with both smaller and larger airports confirm that AIP funding is often combined with DBB delivery. However, as explored in Chapter 3, Section 3.8, there is some flexibility within FAA to allow airports to use DB or CMAR for AIP-funded projects. As noted in the recently revised Airport Owners’ Guide to Project Delivery Systems, FAA staff are most familiar with DBB and may have limited experience with DB (ACI/AGC/ACC 2022). Furthermore, ACI/AGC/ACC notes that FAA’s approach may vary between its regional offices and even among personnel within the same region. In that context, it is essential for an airport to closely follow the requirements outlined in the Airport Improvement Program Handbook (FAA 2019) and engage early with FAA staff to discuss the project and the airport’s plans regarding delivery method. Furthermore, as more projects are delivered through nontraditional delivery methods, airports can leverage that experience to educate FAA staff on the benefits and opportunities associated with those delivery methods.

Other Considerations

Other considerations that may play a role in the PDM selection decision include the experience and availability of in-house staff, project type, and market conditions.

Staff Experience and Availability.

Use of alternative PDMs can be viewed as a strategy to better manage limited internal resources and improve efficiency by shifting more responsibility for project delivery to the private sector. This is particularly true of fixed-price DB, which can entail less owner involvement, because the design–builder has single-point responsibility for design and construction. However, as addressed in Chapter 5, Section 5.2, for organizations that have deeply embedded cultures founded on DBB delivery and hard-dollar procurement methods, implementing more collaborative PDMs can require some training of staff to obtain the negotiation and team-building skills needed to effectively oversee and execute the project.

Project Type.

Several of the airports interviewed during the development of this guide noted that project type can play a large role in their PDM preferences. For example, projects for which design and construction are tied to proprietary equipment or systems, such as baggage screening

and handling systems, are generally viewed as good candidates for a DB approach. Similarly, projects in which the required functionality is readily defined and not subject to wide interpretation of what will meet the specification criteria (e.g., video surveillance/security systems, runway pavements), generally are also considered good candidates for a DB approach. In contrast, complex terminal projects that require significant stakeholder engagement and complex phasing considerations may be better suited to the more collaborative CMAR or PDB approaches, particularly if the speed of overall project delivery is important and there is insufficient time or resources to take the design to the maturity needed to obtain lump sum bids under traditional fixed-price DB.

Market Conditions.

The simplicity, initial price certainty, and risk transfer offered by DBB, and even fixed-price DB, may be more attractive to owners when contractors have the capacity to take on work and are prepared to price risk aggressively to win new projects. In contrast, when industry is busy, potential project participants are likely to be more selective about the opportunities they choose to pursue and the risks they are willing to assume. In such a market, the more collaborative delivery methods of CMAR and PDB can be more effective in attracting qualified proposers and helping to control cost and minimize risk premiums.

2.4.2 PDM Selection Tool

Some owners have developed systematic processes to facilitate the selection of a PDM for a given project. Such processes generally entail considering a project’s goals and constraints and then evaluating the opportunities and challenges associated with each delivery method under consideration, as just discussed in Section 2.4.1. Using such a formal and structured approach can lend transparency and consistency to the PDM selection process, which can help justify the delivery decision to executive leadership and other stakeholders, including the public.

Applying a formal and structured approach to the PDM selection decision can help justify the delivery decision to executive leadership and other stakeholders.

Example PDM Selection Matrix: Nashville International Airport

Nashville International Airport has developed a simple weighted criteria matrix that allows project teams to qualitatively evaluate DBB, CMAR, DB, and PDB (Figure 2-9).

Example PDM Selection Form: Port of Seattle

The Port of Seattle has developed a PDM selection form that allows users to document key project characteristics (Figure 2-10). The form then poses additional questions based on constraints included within the Revised Code of Washington related to implementing specific PDMs. The final step of the form asks users to document the perceived advantages and disadvantages of each project delivery method under consideration on the basis of the following criteria:

- Project schedule: Consideration of critical milestones and construction phasing;

- Project costs: Consideration of competitive bidding, additional alternative delivery contractor costs, change order costs, and other risk costs;

- Project scope/quality: Consideration of level of scope definition, qualifications as part of contractor selection process, constructability, and value engineering during design;

- Stakeholder approval/decisions: Consideration of ownership of design process, stakeholder involvement, and approvals; and

- Airport operations: Consideration of operational impacts or limitations during construction and how much control the airport has with each project delivery method.

Decision Support Framework for Evaluating and Selecting Airport Capital Project Delivery Methods

As a companion to this guide, an Excel-based decision support framework, the Project Delivery Method Selection Tool, was developed to help users in evaluating and selecting suitable PDMs

for their projects. The selection criteria and scoring methodology incorporated into the tool are based on expert judgement informed by

- The researchers’ experiences and lessons learned on past projects;

- In-depth interviews with airports (in which the researchers explored the types of PDMs in use, the drivers behind their use, project outcomes, and the level of satisfaction with the PDMs used); and

- Feedback provided through industry vetting of the draft tool and guide.

The tool should not be construed as yielding conclusive or definitive outputs but, rather, recommendations that can support and frame further discussion and analysis of the merits of the different PDMs under consideration. The Project Delivery Method Selection Tool is available on the National Academies Press website (nap.nationalacademies.org) by searching for ACRP Research Report 267: Selecting, Procuring, and Implementing Airport Capital Project Delivery Methods and looking under “Resources.”