Incorporating Shock Events into Aviation Demand Forecasting and Airport Planning (2024)

Chapter: 14 Step D: Develop Options for Improved Robustness

CHAPTER 14

Step D: Develop Options for Improved Robustness

Generating Ideas for Improved Robustness

Although presented as a separate step, it is recommended that this part of the process be included as a follow-on to the engagement process in Step C. Having determined in Step C the issues arising from the scenario forecasts and areas of concern in current plans, the natural next step is to discuss how these can be addressed, including potential remedies. This should result in a more motivating and productive engagement process to focus on practical ideas to address the possible shocks. It will also reduce the time, resourcing, and scheduling required to bring the relevant participants together.

In much of the literature on strategic risk, responses are categorized into one of four categories:

- Avoid (or exploit for positive shocks),

- Transfer (or share for positive shocks),

- Mitigate (or enhance for positive shocks), and

- Accept.

These are elaborated further in Table 6, which draws on past research in ACRP Report 76 (Kincaid et al. 2012) with additional commentary added. The participants should consider whether the overall approach to the impacts of a shock event falls into one of the four categories, which can then guide further development of the response strategies. For example, the avoid and mitigate responses can involve a mix of planning, financial, marketing, and operational responses while transfer and accept are more likely to involve more corporate (e.g., joint ventures) or financial (e.g., insurance, build up of financial reserves for contingencies). Airport-specific avoid and mitigate responses are discussed in the following subsection. In some cases, the approach may not fall neatly into one of the four categories or may span more than one. For example, an insurance policy may have a significant deductible, so this option would be a combination of transfer (for the insured amount) and accept (for the deductible).

Another consideration is the characteristics and value-added of a response option:

- No- or low-regret options. Decisions or actions that will yield benefits regardless of which scenario materializes and generally make good business sense. For example, an open terminal design that allows great flexibility in the use of the space will provide benefits beyond just coping with the traffic impacts of shock events. Similarly, the use of swing gates or MARS gates (described first in Chapter 8) not only provides greater flexibility in managing different traffic mixes but could also reduce overall space requirements.

- Reactive options. These are actions that would be taken when the shock event occurs. Often, they are specific to one event or a type of event (e.g., the loss of a major carrier, a terrorist attack, etc.). Although reactive, they can be thought out ahead of the event and thus reduce implementation time if and when needed. Airports can develop response plans for specific

Table 6. Categories of risk and shock event responses.

| Threats | Opportunities | Additional Commentary |

|---|---|---|

| Avoid Action is taken to eliminate the impact of a risk. For example, design and build to meet a much higher earthquake, tornado, or tsunami risk. Some threats can be avoided entirely by changing operations or eliminating practices deemed risky. These actions will often require incurring a cost, and eliminating risky practices might disappoint stakeholders or degrade the overall business case. |

Exploit Make a proactive decision to take action and show that an opportunity is realized. See commentary. |

As documented in Part I, some airports expedited facility and capital development plans during the COVID-19 pandemic to capitalize on lower construction costs during the pandemic and reduce disruptions due to the low levels of traffic. This also enabled more reliable project timelines and positioned the airport for strong growth in the recovery period. |

| Transfer The impact of the risk is transferred to another party that is willing to and better able to handle the risk (such as an insurance company or investors in a futures market). Services previously provided by the airport could be transferred (e.g., to the airlines) or contracted out. This may involve higher costs or payment of a fee (e.g., outsourcing to a skilled expert) or a premium (e.g., insurance). |

Share Assign ownership of the opportunity to a third-party that is best able to capture the benefit for the operation. Examples include forming risk-sharing partnerships, teams, or joint ventures that can be established with the express purpose of managing opportunities. |

Many airports have business continuity or business interruption insurance—insurance against a loss of business due to facilities being damaged or out of action (e.g., due to a fire or hurricane). However, in the case of COVID-19, there was no property damage, and some of the airports interviewed in Part I indicated that the insurance had exclusions for pandemics, communicable diseases, and “acts of God.” |

| Mitigate Action is taken to lessen the expected impact of a risk. Mitigation generally requires positive actions, such as an investment, additional staff, or a change in procedures, and can have a resource cost. These actions should be considered new practices and controlled like any other airport operation. They may affect the airport operating budget but may be preferable to a “do-nothing” or “wait-and-see” approach (see discussion on evaluation in the next subsection). |

Enhance Take action to increase the probability (e.g., marketing and incentives to attract a major new carrier hub) and/or impact the opportunity for the benefit of the operation. Seek to facilitate or strengthen the cause of the opportunity, and proactively target and reinforce the conditions under which it may occur. |

One form of mitigation that may be effective for shock events is the development of action plans or manuals to guide decision-making during and after a shock event. This would be similar to the emergency response plans that airports develop for runway incidents, fires, and other emergencies. |

| Accept No action is taken. After being unable to avoid, transfer, or mitigate the threats, the operation will be left with residual risks – threats that cannot be reduced further. In active acceptance, airport management may set up a “contingency reserve fund” to account for the residual expected value of the remaining risks. A passive form of acceptance simply acknowledges the risk and moves forward with existing practices without reserves, which may seem sensible for risks with small expected values. |

Accept Take no action when a response may be too costly to be effective or when the risk is uncontrollable and no practical action may be taken to specifically address it. |

A number of the airports interviewed in Part I indicated that cash reserves that the airport had built up over previous years had aided the airport’s response to the pandemic and its ability to manage its resources. Similarly, at least one transoceanic air navigation service provider had developed a traffic stabilization fund (reserve) to be used for either economic cycles or shock events. |

- types of shock events similar to the emergency response plans that airports develop for runway incidents, fires, and other emergencies. These response plans are discussed in more detail in the next subsection.

- Preemptive options. These are options that require changes to the airport planning and strategy and may take considerable time to implement. They may also have substantial cost implications. For example, a modular terminal design that allows incremental development of the terminal in response to traffic growth and enables the pausing or acceleration of capacity growth may involve greater design and construction costs than if the terminal were to be built in one go.

To expand on the modular design, this approach may involve higher total costs as additional construction elements are required. A temporary end wall might be required at the end of the first phase of the building—a wall that would then need to be removed when the next phase is constructed. However, the present value of the construction costs of a modular design may be lower, as much of the expense is deferred to the future. Depending on interest rates, the present value computation of a modular design may be lower than building the entire terminal in one go. There are other advantages of modular design—such as the ability to incorporate new technologies and new nonaeronautical revenue opportunities—and to address future changes in regulations that would require an expensive refit of an all-in-one-go approach. The refit costs of new security regulations and required equipment after 9/11 are examples of how modular designs can better accommodate changing requirements for physical space planning compared to retrofitting existing facilities and the cost to change design plans not meant to be modular.

The no-regret and reactive options will generally be relatively straightforward and fairly low-cost to implement. The preemptive option may be more contentious with higher financial commitments, requiring further analysis and scrutiny. Such analytical approaches are set up in ACRP Report 76, including expected net present value and cost-benefit analysis, which weigh the cost of such mitigation measures against the benefits in conditions of uncertainty (Kincaid et al. 2012).

Airport-Specific Response Strategies

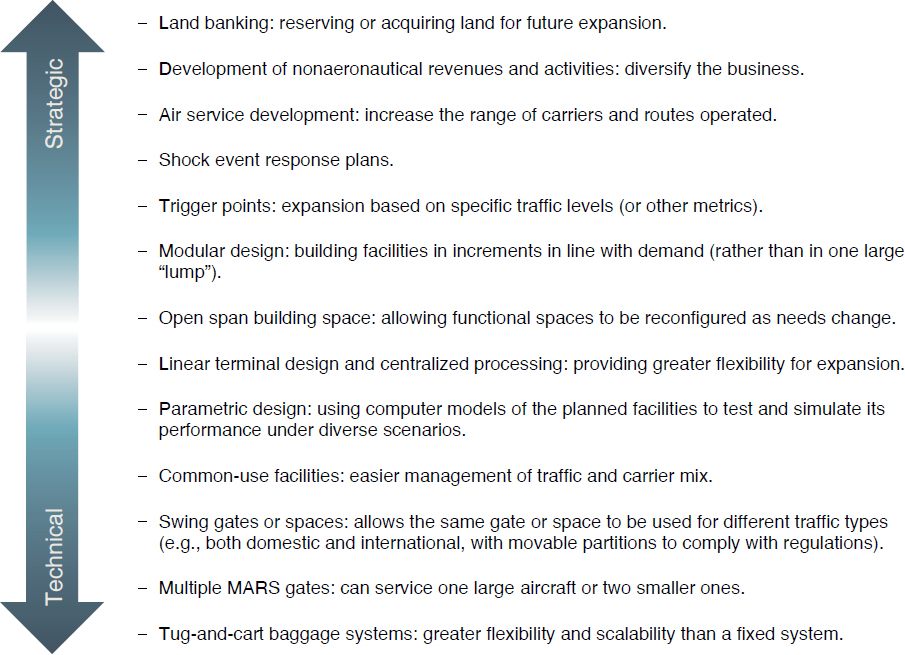

There are various strategies and actions airports can and do take to address uncertainty. While not specific to shock events, some of these apply to such events. Based on a review of previous research, observation at airports generally, and the experience of the research team, these strategies are summarized in Figure 37, ranging from strategic to technical. Further details on these approaches were discussed in Part II. The list is not exhaustive and is designed to act as a starting point for developing options. The specific circumstances of the airport and the shock risks it faces may lead to other solutions.

Preparedness and Response Plans

The development of shock event response plans has been raised in the previous sections and is discussed further in this section. The development of response plans is a relatively low-cost way of enhancing robustness to shock events and has parallels with the approach already used by airports to respond to emergencies and accidents.

The development of response plans is a relatively low-cost way of enhancing robustness to shock events and has parallels with the approach already used by airports to respond to emergencies and accidents.

Airports are already familiar with the development of emergency response plans (ERPs). Currently, these generally address safety and security issues, although there are other types of events that they have to address as well.

Some types of ERPs are a regulatory requirement. FAA 14 CFR § 139.325 – Airport emergency plan states the following.

§ 139.325 Airport emergency plan.

- In a manner authorized by the Administrator, each certificate holder must develop and maintain an airport emergency plan designed to minimize the possibility and extent of personal injury and property damage on the airport in an emergency. The plan must–

- Include procedures for prompt response to all emergencies listed in paragraph (b) of this section, including a communications network;

- Contain sufficient detail to provide adequate guidance to each person who must implement these procedures; and

- To the extent practicable, provide for an emergency response for the largest air carrier aircraft in the Index group required under § 139.315.

- The plan required by this section must contain instructions for response to–

- Aircraft incidents and accidents;

- Bomb incidents, including designation of parking areas for the aircraft involved;

- Structural fires;

- Fires at fuel farms or fuel storage areas;

- Natural disaster;

- Hazardous materials/dangerous goods incidents;

- Sabotage, hijack incidents, and other unlawful interference with operations;

- Failure of power for movement area lighting; and

- Water rescue situations, as appropriate.

. . .

- The plan required by this section must contain procedures for notifying the facilities, agencies, and personnel who have responsibilities under the plan of the location of an aircraft accident, the number of persons involved in that accident, or any other information necessary to carry out their responsibilities, as soon as that information becomes available.

The development of an ERP involves identifying the resources that will be needed, where these can be obtained, the staff needed, and clearly stating the duties and responsibilities of the individuals (and organizations) in the response team. It also identifies actions and their sequence. This is a method and process that addresses certain types of shock events. It is a process that could be used to address other types of potential shock events. Item b (5), natural disaster, which is listed in the regulation, is a type of shock event.

As currently constructed, most ERPs focus on operational and human resource issues and tend to be largely related to the immediate response required in an emergency. These have been very successful in preparing airports for various types of emergencies and have been invaluable in practice. While they are focused on an immediate response to certain types of shock events, they also address some medium-term issues. For example, to mitigate the harm from an emergency, the ERP development process may identify the need for human and physical capital. Management may recommend and the board approve procurement of emergency response equipment or may undertake certain changes to the physical layout of the airport. Of particular importance is identifying training and skill-maintenance needs. In some cases, additional staff positions may be identified and hired. These are resources that, hopefully, may never be used, but their positioning will be invaluable should the shock event occur.

For certain types of potential shock events, an ERP approach would be a familiar and appropriate starting point. Additional steps would be required. For example, an ERP to deal with a major earthquake that destroys key parts of the infrastructure is focused on immediate-term actions. The ERP, however, typically does not address the medium-term restoration of the infrastructure. Incorporating shock events into airport planning would need to address the medium-term needs.

Two other modes of transport guide some aspects of short- to medium-restoration of capabilities: highways and railroads. Railroads experience floods or other weather-related or natural disasters that destroy sections—sometimes large sections—of track infrastructure (earthworks, ties, rails, ballast), including bridges. This is also true of state, county, and local highway departments. A number of these organizations identify, as an advance contingency, lists of potential external contractors and suppliers and prequalify them so that they can quickly be engaged for remedial supplies and work. A complementary approach is to identify and track availability of certain premade structures. Some highway departments keep track of bridge truss sections, for example, which may have been surplus to a recent construction project or which have been fabricated but not yet deployed on new infrastructure. This provides a starting point for remedial resources. In the airport context, an example might be tracking items, such as loading bridges, that were replaced when a terminal expansion was undertaken. Such resources could be accessed quickly to allow full operations to resume.

An ERP generally does not address financial issues. A major earthquake that destroys an airport and its region may result not only in financial capital needs for restoring airport capacity but also may suppress passenger and cargo demand for a prolonged period. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 left Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport relatively unscathed, which allowed it to serve as critical infrastructure for the disaster response. However, the destruction of major areas of the city resulted in reduced passenger traffic for several years, as documented in Part II. Many major conventions, for example, could not be hosted, and important parts of the population relocated to other regions, in many cases for years, while housing stock was reconstructed. Other global examples are found in the earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand, and a tsunami in Sendai, Japan.

Planning for shock events should go beyond the immediate-term scope of an ERP and address financial and human resource resiliency. Airport charging structures and policies may

need to be addressed. Compensatory (dual till) policies allow an airport to retain net income from nonaeronautical sources to build financial reserves for future projects and contingencies. Residual pricing (single till) policies generally do not build financial reserves or only make modest provisions for building contingency financial reserves.

Just as airport ERPs are typically managed by an officer who, working with a team, is given responsibility for developing plans, so too airports might convene a team to consider potential shock events and develop plans. This might consist of the ERP team but with an expanded set of expertise. The team should include individuals from operations, planning, capital projects, finance, marketing, and communications.

The response plan itself should provide key information and guidance such as

- Persons responsible within each department;

- Actions to be taken by those departments (this can be delineated over the timeline of the event, e.g., on the outside, during its development, and in the aftermath);

- Interactions with stakeholders and customers;

- Communications with government and media; and

- Recognition that the event may occur in ways not anticipated and provide options for alterations to the plan.

Simplifying the Process

Many of the possible strategies for addressing shock events (as listed in Figure 37) can also provide general cost savings for airports. For example, using swing or MARS gates can reduce the overall number of gates and terminal capacity required. As already highlighted, shock event response plans are a relatively low-cost method for addressing shock events, and for smaller organizations, the plans can be fairly short documents.

Outcome

This step will generate possible modifications or enhancements to airport plans and strategies that enhance the robustness of the airport to shock events. Where these modifications involve significant money and resources, further analysis may be required to evaluate their cost-effectiveness. The development of response plans will provide airports with “off-the-shelf” strategies to address shock events rather than having to develop the strategies in real time.