Incorporating Shock Events into Aviation Demand Forecasting and Airport Planning (2024)

Chapter: 16 Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport

CHAPTER 16

Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport

Introduction

Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport (BHM) was previously profiled in Chapter 4. BHM is a small hub airport operated by Birmingham Airport Authority, 5 miles northeast of central Birmingham, Alabama. It is the largest commercial service airport in Alabama, handling 1.5 million enplanements in 2019.

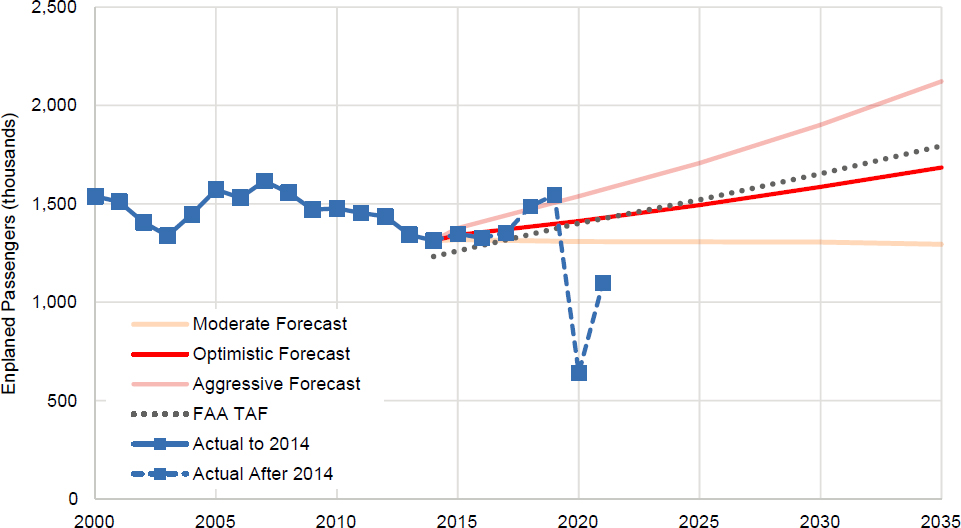

The methodology was applied to the airport during the period its airport master plan was being developed; the master plan was finalized in July 2018 (Birmingham Airport Authority 2018). The master plan set out the forecasts of traffic development to 2035 and the facility development that would be needed to accommodate that traffic and modernize the airport in this period and beyond. The forecasts for the master plan were developed in 2014, with forecasts of air passengers, aircraft movements, based aircraft, and air cargo tonnage generated for the period 2014 to 2035. The passenger forecasts are shown in Figure 38. To account for the inherent uncertainty of aviation demand forecasting, the forecast team generated three forecasts that captured different economic and airline industry conditions using regression modeling:

- Moderate: Employment and regional GDP to grow at a similar rate to recent trends, with regional GDP growing at 1.3% to 1.5% per annum (in real terms). Airline fares at BHM are assumed to outpace the region’s economic growth, resulting in some demand suppression.

- Optimistic: Employment and regional GDP to grow at 50% higher than the moderate forecast and airline yields to grow at a slower rate than the national trend.

- Aggressive: Employment and regional GDP to grow in line with historical highs, in the range of 2.7% to 3.2% per annum for GDP growth. Airline yields to grow at a slower rate than the optimistic forecast.

Under the moderate forecast, traffic was forecast to decline by an average of −0.1% per annum from 2014 to 2035, while the optimistic scenario forecast growth of 1.2% per annum and the aggressive scenario of 2.3% per annum. Additional forecasts were also generated using a market share methodology, where traffic at BHM was forecast based on its projected share of forecast Alabama or national traffic. These market share forecasts fell within the range of the regression-based forecasts.

Figure 38 also shows the FAA Terminal Area Forecast (TAF) referenced in the master plan (published in February 2014). The TAF was close to the optimistic forecast as well as the market share forecasts (not shown) produced by the forecast team. For master planning purposes, the FAA TAF was selected as the primary forecast informing the airport master plan. This forecast growth of 1.8% over the planning period is higher than the optimistic forecast.

As the chart shows, traffic development after the forecast was produced closely matched the FAA TAF and optimistic forecast up to 2017. In 2018, traffic grew by 9.9% and was tracking

above the aggressive forecast. This growth was due to general demand growth, the entry of Frontier Airlines (who subsequently ended service in late 2019), and capacity additions by a number of network carriers. As previously documented, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a 59% decline in passenger volumes in 2020 and a partial recovery in 2021.

Immediately prior to the master planning process, the airport has completed a terminal modernization program and runway extension. This put the airport in a good position to accommodate growth; therefore, the development of this master plan emphasized three areas:

- Accommodating new design standards that enhance safety and efficiency;

- Addressing operational and developmental constraints needed to support growth; and

- Creating development areas to support revenue generation.

The master plan also considered the need for a parallel runway. The airport currently has two crossing runways. The third runway would be parallel to the main runway. It was assessed that the runway would not be required before 2035, and traffic trigger levels were set for when the process of planning and building the runway should be started. The master plan set out a capital improvement program totaling $362.3 million (in 2016 dollars), with the following timeline:

- Short-term (1–5 years): $125.8 million.

- Medium-term (6–10 years): $149.9 million.

- Long-term (11–20+ years): $86.6 million.

Major capital projects included culverting or realigning a waterway (Village Creek) that ran through the airport (this accounted for over $100 million of program costs), reconfiguration of the taxiways and runway improvements (for regulatory reasons rather than capacity), road realignment, air cargo facility expansion, and site preparation and development.

Application of the Methodology

The five-step methodology was applied to BHM as described herein.

Step A: Identify Shock Events of Interest

The identification of potential shock events relevant to BHM was made through structured brainstorming discussions within the ACRP research team as well as information on shock events from previous tasks and information obtained from the master plan document and other sources. The list of identified shock events is shown in Table 7. The list is fairly wide-ranging without any filtering applied; the next stage of the process narrows the list to those events considered most pertinent.

Step B: Develop Scenario Forecasts That Incorporate Shock Events

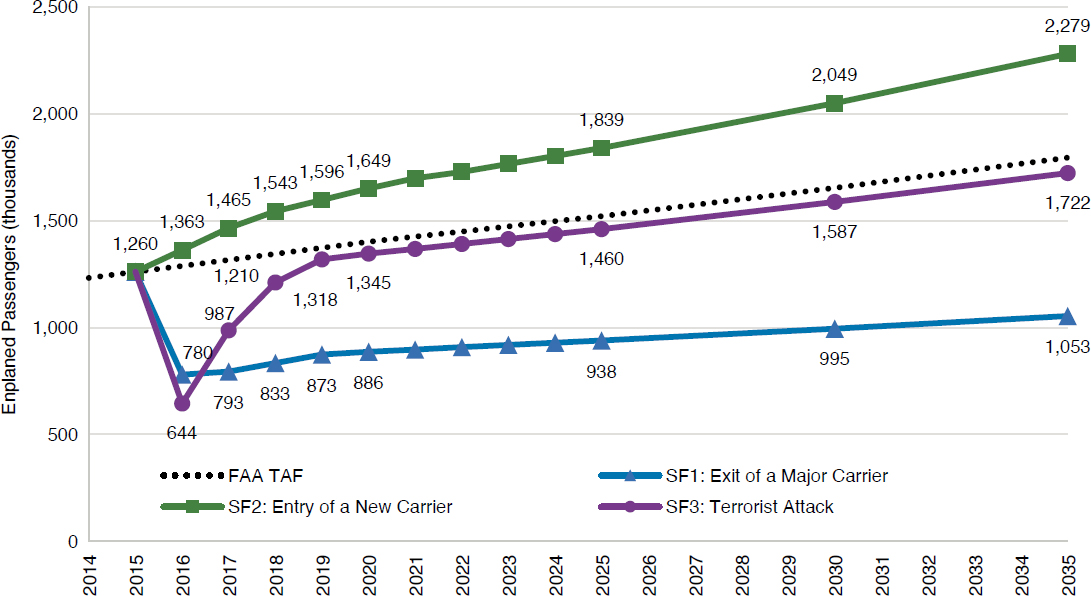

The events in Table 7 were shortlisted to three that were considered most relevant and challenging:

- Loss of a major carrier. While BHM was not highly dependent on a single carrier in 2014 (which is still the case in 2022), two carriers accounted for more than 60% of the traffic. The loss of one of those carriers would have significant implications for the airport. It was recognized that this can be linked to a recession event as an economic downturn may precipitate the carrier exit, so this scenario covers that aspect as well.

- Entry of a new carrier. Ensuring the airport has contingencies if more rapid growth does occur.

- Terrorist attack. Using this scenario forecast could cover multiple potential events where there is a sharp drop in traffic followed by recovery.

Scenario forecasts were developed for these three events, which model the deviation from the selected forecasts used in the master plan (the FAA TAF of February 2014). The key assumptions in the three scenario forecasts are summarized below.

Scenario Forecast 1: Loss of a Major Carrier

- The event is assumed to occur after 2 years (i.e., 2016). At this point, the national or regional economy is weakening, resulting in a softening demand for air travel.

- The largest carrier at BHM, Southwest Airlines, is assumed to exit at the start of 2016, due to a change in airline strategy or poor market performance.

- All of Southwest’s services are terminated at that point. In 2014, Southwest Airlines was operating seven routes from BHM to Dallas Love Field, Baltimore, Orlando, Chicago Midway, Tampa, Houston Hobby, and Las Vegas.

- Immediately after the exit, some traffic is recaptured through higher-load factors on the remaining carriers where they serve the same market or can provide connecting alternatives to the lost routes. For example, United Airlines operated to Chicago O’Hare and Houston George Bush and American Airlines operated to Dallas Fort Worth and Washington National (the latter a possible alternative to Baltimore).

- Carriers serving these overlapping markets increase capacity over the next 2 years to recapture some of the demand, with capacity on those markets increasing by 25% over that period. Other routes (Orlando, Tampa, Las Vegas) are assumed to remain unserved.

- Long-term traffic growth follows the master plan forecast trend.

The purpose of this scenario forecast is to examine the impact of a negative event, so the assumptions made are fairly conservative. For example, it is possible that with the exit of Southwest, another LCC may enter the market operating additional routes or that the existing carriers will in-fill more of the lost capacity. However, it has been assumed that only modest capacity recovery will occur, reflective of a weaker economic environment.

Table 7. Identified shock events based on the 2014 outlook.

| Event | Description of Impact | Timeline and Aftermath |

|---|---|---|

| Major carrier exit | Loss of a major carrier. In 2014, Southwest Airlines (including AirTran Airways) accounted for 42% of passenger traffic and Delta (mainline) 20% (Birmingham Airport Authority 2018). AirTran Airways was acquired by Southwest Airlines in 2011, with the merger finalized in December 2014. The figure for Delta does not include regional services. | The immediate impact of Southwest’s exit would be a significant loss of traffic, particularly as the routes operated by Southwest did not fully overlap with other carriers. Some capacity may be in-filled by other carriers, but there would be uncertainty whether a full recovery would occur. |

| The loss of Southwest Airlines would result in not just the loss of capacity but also connectivity, as the airline operated seven routes at the time, while the network carriers operated 2 to 3 routes to their major hubs (American Airlines added more routes in 2015). | While there is the potential for traffic to remain depressed for some time, it may not follow the pattern seen at airports such as STL (see Chapter 5) as BHM does not act as a connecting hub in the way that STL did (much of the traffic lost at STL with the exit of American Airlines was transfer traffic). | |

| Entry of a new carrier | Entry of a new carrier, e.g., a ULCC such as Allegiant Air or Frontier Airlines. As documented previously, the entry of these carriers has stimulated significant volumes of incremental passenger traffic, often at a rapid rate. Frontier did in fact operate at BHM in 2018 and 2019. | The entry of a ULCC may result in rapid traffic growth, especially if there is a competitive response by incumbent carriers. |

| The long-term success of the carrier is a risk factor with this event. The carrier could later exit due to low demand or a change in airline strategy, or an existing carrier could decide to exit the market. | ||

| Severe recession | A severe recession along the lines of the 2008–2009 Great Recession. Such a recession would lead to declining passenger demand, airline capacity cuts, and possible airline restructuring and rationalization. | Nationally the 2008–2009 Great Recession led to an 8.7% decline in traffic and a 7-year recovery. BHM experienced an 8.9% decline from 2007 to 2009, with traffic still not recovered by 2014. |

| Another recession of this scale would result in further declines and a protracted recovery. | ||

| Loss of local industry | Loss of a major regional employer such as the Honda manufacturing plant or one of the financial or health corporations based in Birmingham. Such a loss is expected to result in a loss of corporate travel as well as discretionary travel by people previously employed at those businesses. | Short-term decline in traffic, followed by a decline in the long-term growth trend. |

| Terrorist attack | A terrorist attack targeting aviation in the United States, leading to a sharp decline in traffic. | BHM experienced declines in the two years following 9/11, which was also due to economic factors, and did not fully recover until 2005. |

| Another terrorist attack would result in short-term declines in traffic due to loss of consumer confidence and government security requirements. Recovery would be similar to that after 9/11. Depending on the nature of the attack, it could also result in new or additional security requirements, affecting passenger processes and airport design. | ||

| Pandemic | BHM is impacted by a pandemic event, which may be regional, national, or global. | BHM was not affected by past pandemic events. The potential event impacting BHM would be expected to follow a similar pattern to SARS, with a short-term and large-scale decline in traffic due to government controls on air travel. The event is anticipated to last months rather than years, with a fairly rapid recovery as was seen with SARS. |

| Climate event or climate change | Birmingham’s inland location means that it is protected from the more destructive effects of Atlantic hurricanes. However, it is subject to severe thunderstorms and tornadoes. The assumed event would be an “extreme” weather event resulting in significant damage to the airport and city. | A sharp, short-term decline in traffic due to infrastructure damage, followed by recovery over the next 2 to 3 years. An extended recovery is not anticipated such as that experienced by MSY due to the considerable population decline and loss of tourism following Hurricane Katrina. |

Scenario Forecast 2: Entry of a New Carrier

- The event is assumed to occur after 2 years (i.e., 2016). Economic conditions are generally positive.

- A new LCC starts operation at the beginning of the year, operating 166-seat aircraft, and builds up service on routes not served from BHM as well as competing on some existing routes.

- The carrier starts service in the first year to three destinations with an average frequency of four times per week, and the carrier can achieve an average load factor of 80%.

- It is assumed that 90% of its traffic is incremental (10% is taken from other services at BHM). The entry of the carrier draws a competitive response from existing carriers (fare reductions and service increases), so the overall effect has a strong stimulatory impact on passenger traffic.

- In the second year, three more destinations are added (at four times per week) and two more in the third year.

- Frequencies and destinations grow in the following years so that 5 years after entry, the carrier is operating an average of six departures a day (less than half the level of operations by Southwest Airlines in 2014).

Scenario Forecast 3: Terrorist Attack

- Terrorist attack occurs in 2016 targeting aviation, directly impacting air services at BHM.

- The government introduces strict measures to enhance aviation security, and consumer confidence is hit, resulting in a 50% decline in overall traffic volumes that year (more severe than the impact of 9/11).

- As new security measures are introduced, demand starts to return, recovering to 75% of preevent levels after one year. By the second year, traffic is close to full recovery, at 96% of preevent levels.

- Traffic development returns to the preevent trend after 3 years.

The resulting scenario forecasts are shown in Figure 39 alongside the FAA TAF used for the master plan. The three scenario forecasts show significant deviation from the master plan forecasts

taken from the FAA TAF. Scenario Forecast 2 (entry of new carrier) results in a 27% growth over 3 years (compared with 9% in the master plan forecast) and Scenario Forecasts 1 and 3 result in declines of 40% to 50%.

Compared with the forecasts developed in the master plan shown in Figure 39, the long-term range of the scenario forecasts is only slightly wider. The 2035 forecasts range from 1.05 to 2.28 million enplaned passengers compared with the 1.29 to 2.12 million range in the original master plan forecasts (shown in Figure 38). However, the scenario forecasts illustrate a more rapid change in traffic caused by the shock event, against which the master plan can be evaluated. Additional detail can be added to the forecasts, if required, by also producing forecasts of aircraft operations and peak-period traffic.

As mentioned previously, the purpose of these scenario forecasts is not to produce a more accurate forecast. None of these forecasts capture the traffic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, they provide a way of challenging and testing the master plan, as shown in the next step of the process.

Step C: Scenario Implementation

The next step of the process is to evaluate how the airport business would cope and respond to the scenarios previously developed. The idea is to stress test the master plan (and other aspects of the airport). Another elicitation exercise was undertaken with the ACRP project team to assess the impact of the scenario forecasts on five aspects of the business:

- Planning;

- Finance;

- Marketing and commercial activities;

- Operations, security, and safety; and

- Community and stakeholders.

The assessment is summarized in Table 8.

The assessment found areas of strength in the master plan and the airport’s situation. Following the previous terminal and runway work, the airport was well-positioned to handle upside shocks, while the master plan did not involve a large commitment to capital expansion, mitigating downside shocks. As with most airports, fairly rapid and potentially sustained changes in traffic levels (particularly declines) would present challenges to airport planning and management. Possible measures to enhance the robustness of these shocks are explored in the next step.

Step D: Develop Options for Improved Robustness

Having determined in Step C the issues arising from the three scenario forecasts, the next step was to determine what actions could be taken to address these issues and improve the robustness of the airport plans. Although presented as a separate element, the process of brainstorming and developing possible remedies and mitigation actions was conducted by the ACRP research team at the same time as Step C.

Table 9 sets out the proposed strategies and approaches to enhance the robustness of the three scenario forecasts. The development of these options draws on the ideas set out in Part II of the guide as well as previous research in ACRP Report 76 (Kincaid et al. 2012).

The proposed modifications to the master plan are based on an examination of how aspects of the plans would be impacted by the scenario forecasts and identifying areas where the plan could be modified or adapted to these conditions. While maintaining the overall direction of

Table 8. Impacts of the scenario forecasts (SF), BHM.

| Area | SF1-BHM: Loss of a Major Carrier | SF2-BHM: Entry of a New Carrier | SF3-BHM: Terrorist Attack and Aftermath |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning | Given recently completed airport improvements (e.g., terminal modernization and runway extension), the 2018 master plan was largely focused on investments to achieve operational improvement, regulatory compliance, and revenue diversification. Major facility expansion was not anticipated out to 2035. Some elements of the plan could be delayed or slowed in light of reduced traffic, but other elements would still need to go ahead to meet operational and regulatory requirements. The master plan identified traffic trigger points for very long-term developments (e.g., a parallel runway). |

The master plan determined that there was generally sufficient airfield and terminal capacity to handle forecast growth to 2035. Therefore, more rapid growth could largely be accommodated. (The terminal modernization was planned based on forecasts of up to 2.5 million enplanements, which is higher than the 2035 forecast in SF2.) However, there could be capacity constraints in certain areas or processes, particularly if the new carrier increases peak-period traffic volumes. Plan to manage within existing facilities, given long-term viability is uncertain. |

Master plan is largely focused on operational improvement, regulatory compliance, and revenue diversification. These plans may not need to be delayed or delayed only for a short period. As with 9/11, the event could bring about additional security requirements and processes. The terminal modernization has improved security processes, and the 2018 master plan includes improvements to perimeter security. |

| Finance | The loss of traffic would significantly impact aeronautical and nonaeronautical revenues. Airline agreement is a mix of residual (airfield) and compensatory (terminal), so airport charges will likely rise, reducing some aeronautical revenue losses. Cost reductions will need to be sought, particularly on nonaeronautical activities. Bond covenants require a certain amount of cash on hand and reserves. The event would likely lead to a dramatic drop in revenue, and action may need to be considered to maintain the reserves in order to fulfill those covenants. |

Entry of a new carrier would provide upside revenues, especially around terminal charges and nonaeronautical revenue (e.g., parking, concessions). Operating costs could also increase to manage the additional volume. |

Reduced aeronautical and nonaeronautical revenues during the recovery period. Degree of government support (as occurred after 9/11) is hard to ascertain. Airlines will also bear some of the revenue risk. The impact on available reserves would need to be monitored to meet bond covenants. Increases in capital and operational costs are possible due to additional security measures. |

| Marketing and commercial activities | Air service development activity will need to ramp up to help replace service. May need to increase the marketing budget at a time when airport revenues are challenged. Master plan also covered cargo and commercial activity, which could be accelerated to offset passenger losses. |

Passenger mix may change (e.g., more leisure travelers), which could impact the commercial revenue performance and mix. | Use incentives and other air service marketing to encourage the return of air service and to aid airline partners. |

| Operations, safety, and security | Declining traffic levels may lead to operational reductions (with corresponding cost savings) balanced against the need to maintain safety and service levels. | Would increase the need for greater operational capacity, especially at peak times. | Lower traffic levels may reduce operational requirements, which may be offset by additional security requirements. |

| Community and stakeholders | Will need to work with airport stakeholders and contractors to ensure business sustainability and achieve cost reductions. Significant loss of connectivity for the community. Work with local tourism and business representatives to develop a plan to grow air service. |

Largely beneficial for community connectivity. Potential for greater aircraft noise (or perceived noise), following declines in air traffic and associated noise (as of 2014), although traffic levels would still be below historical highs. | Will need to work with airport stakeholders and contractors to ensure business sustainability and achieve cost reductions. |

Table 9. Options for improving robustness at BHM under the scenario forecasts.

| Scenario Forecast (SF) | Mitigation/Robustness Options |

|---|---|

| SF1-BHM: Loss of a major carrier | Evaluate Plan Optionality Identify elements of the master plan that could be postponed or modified in the event of a large traffic decline in order to reduce capital and operating expenditures. This would involve separating elements of the capital development plan that are capacity-related from those that are related to maintenance or regulatory requirements. It can also identify parts of the existing facility that could be converted or shut down. This identification would need to balance cost savings with ensuring that the changes do not jeopardize the ability to recover and grow traffic in the future. |

| Modular Design and Trigger Points Related to the optionality, identify where the plans for the airfield and terminal facilities can cost-effectively be made modular and incremental so investments are as closely aligned with traffic as possible and provide the flexibility to delay development if necessary. Identified trigger points, in terms of annual or peak traffic, would determine the timing of the development. Downside trigger points could also be identified to determine when plans should be slowed down or facilities converted or shut down. |

|

|

Shock Event Response Plan The response plan would identify the actions that need to be taken across the organization, should the event occur. This includes the planning items above but also covers other departments and areas:

|

|

| SF2-BHM: Entry of a new carrier | Evaluate Plan Optionality Identify elements of the master plan that may need to be accelerated or modified as a result of higher traffic volumes. The overall facility has capacity for further growth but there may be specific areas of constraint. The evaluation should also consider additional facility requirements from the incremental traffic that are currently not within the master plan (e.g., terminal security processing, commercial facilities, employee and public car parking). These elements could be identified and characterized at a high level so that the information can be drawn upon if the event occurs. |

| Modular Design and Trigger Points The use of modular design and trigger points will minimize the risk of committing to significant capital investment when it is uncertain how the traffic will develop and whether the incremental growth will be sustained. Identified trigger points, in terms of annual or peak traffic, would determine the timing of the development. |

|

|

Shock Event Response Plan The response plan would identify the actions that need to be taken across the organization should the event occur. This includes the planning items above but also covers other departments and areas:

|

| Scenario Forecast (SF) | Mitigation/Robustness Options |

|---|---|

| SF3-BHM: Terrorist attack | Evaluate Plan Optionality/Modular Design and Trigger Points As with the other scenario forecasts, the identification of plan optionality and the use of modular design and trigger points will allow the airport to adapt the plans to changing traffic conditions. Additional consideration would also be given to the potential for new security requirements arising from the event. While impossible to predict in detail, mitigation measures include identification of terminal space that could be used for future expansion of passenger or luggage screening. This space could be initially allocated to other purposes (e.g., retail, office space) until it is required for security purposes (or in case it is never required). When required, the space can be converted to security. |

|

Shock Event Response Plan An event response plan can also be delivered that addresses anticipated actions and changes required in the short and long term:

|

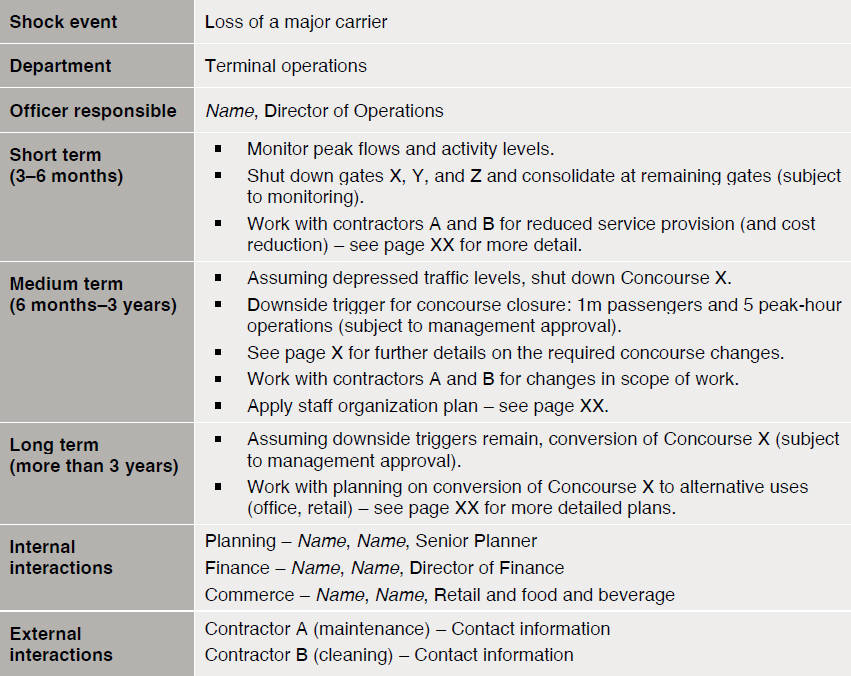

the 2018 master plan, consideration is also given to how more optionality and flexibility can be added to the plan to manage shock events. Outside of the master plan, the main output is the “shock event response plans.” Similar to ERPs, these involve multiple departments (e.g., operations, planning, capital projects, commercial, finance, marketing, and communications), and set out the parties involved and actions to be taken. Unlike ERPs, these plans will be generally less prescriptive, as the exact nature and timing of the event is hard to predict, and with a longer-term focus. The aim is to give the airport a head start in dealing with a shock event and set out a broad game plan or checklist for the organization while allowing sufficient flexibility to address changing conditions.

An example is given in Figure 40 with summary information for one department, terminal operations (the example is not based on BHM), although airports may prefer different formats. In the example format, a summary of key actions is provided, with linkages to other areas of the shock event response plan for more detail.

Step E: Ongoing Monitoring and Vigilance

Step E relates to the ongoing monitoring of potential shock events and updating of planning and processes where necessary. The aim is to maintain ongoing vigilance around the development of potential shock events and ensure that the airport continues to be well-positioned to manage these shocks if they occur. This can involve the following:

- Monitoring and warning. Individuals identified in Step D would be tasked with monitoring identified shock events and possible new events (e.g., airline financial distress, WHO advisories). This can be folded into existing risk management processes. Concern about developing events (e.g., outbreak of a novel virus in some part of the world) can be communicated to management (and if relevant, other stakeholders) and meetings undertaken to determine possible responses and preparation.

- Regular updates. Quarterly or half-annual update memos are produced, incorporating assessments and tracking of potential shock events and other uncertainties, and circulated to the relevant airport team members.

- Reassessment annually or biennially. Reassess or redo Steps A to D to ensure that the airport and its plan remain well-positioned to shock events as conditions change. The aim is not to rewrite the plan every year but to allow it to respond to evolving situations and potential shock events. This assessment could be incorporated into the airport’s reporting, such as annual reports.

The ultimate aim of these exercises is to enhance and maintain awareness of the potential impact of these shock events and for that awareness to continually feed into the ongoing and day-to-day planning, financing, and management of the airport.